South China Sea Basin - Army University Press Spots/Documents/C… · economic reforms restrains...

Transcript of South China Sea Basin - Army University Press Spots/Documents/C… · economic reforms restrains...

South China Sea BasinColonel John B. Haseman, US Army

Copyright 1993

With all of the recent changes around the world, it is easy to focus onone region of the world at the expense of other areas. The author ex-amines changes in the South China Sea basin since the breakup of theSoviet Union. He looks at the different threats to the region and howeach impacts on the region. He discusses the regional military forcesand their efiect on secun”ty. Finally, he looks at the role to be played bythe Association of Southeast Asia Nations.

T.

HE SOUTH China Sea basin, long a stra-tegic region, has changed in character as

the world p{~litical climate has changed. F~mner-ly an area of superpnver c(mfhmtat i(m and c~m-petiti~m f(m influence and p(~iver, the region issuccessfully adjusting u) a nmv iv(~rld order.While it c(mtinues to be a regi(m t~f major na-t icmal interest to the United States, the coun-tries in the S~mth China Sea basin nmv Icx)k tc)-

ward economic cle~’el~lpment and regitmalharmony as their pritne (~hjectites, rather thanthe need to l-dance the c~mflicting interests ofthe supetp~~vers.

The United States c(mtinues t~) place greatemphasis on the regitm and, as the last super-pww-, remains the preeminent military p(mvr inthe region. Htmwver, c(mpetititm for the ~~liti-cal and ec(m(>mic base ~~finfluence in the regi(m

must he shared tt> varying degrees with outsideregional powers such as the Comm(mweakh ofIndependent States (CIS), China, Japan, Tai-wan and the Republic of K(~rea. But the US hasmaintained its influence and credibility throughmore than 15 years t~fp(~st–Vietnam ~~licy eval -uation, while the breakup of the Soviet Unionand the continued struggle ~>ver political andeconomic reforms restrains China. Tb one ex-tent or another, countries with interests in the

South China Sea regi[m ha~e embarked on anew ma t~f political change in v’hich economic

and s~xial issues will become increasingly moreimportant t(} maintain regi~mal stabili~.

Mt~st significantly, the countries of the Asso-ciati(m t>f Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN )have thcmscl~ws gained a greater appreciation oftheir owm strategic imp(wtance and are, f(n- them~~st part, riding a tide of str(mg economic~q-o~vth. Realizing the increased impmance ofec~m(~mic devek>pment, trade and ct>mmerce,

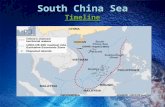

OCEAN K-$ k’-dx-l”s

%- WQ-. ‘

SOUTH CHINA SEA BASINAND

SURROUNDING AREA a

The ebb atiflow of historypkhysa role in re~”orudthreatperceptibns.The communist coup attempt in Indonesti

in 1965 and the long communist insur-gency in Maktysia color those countnies’view of the threat to&y. Vietnam, wilh amilhmnium of struggle agtu”nstChinu,

renun”nssuspicwus of that countrydespite Chinese assistance in Vietnam’s

successful wars with France and theUnited States.

they take a new view of regional security as theymodernize their military forces. Fortunately, thisprocess is directed at improving individual and

collective security against perceived threats from.-outside the immediate arena. There is no poten-tially debilitating arms race among these coun-tries, all of which are friendly to the UnitedStates and to each other.

Differing Views of the ThreatThe major strategic threat in the South China

Sea region is the potential for conflict among na-

tions contesting claims of sovereignty. The gov-

ernments in the region have differing views of—the outside threat. Indonesia and Malaysia, for

example, base their security policies on a viewthat the People’s Republic ofChina (PRC) posesthe main threat to their security because of pastexperience. The Chinese threat is based not ona capability to mount a militaq invasion but onthe historical experiences that these countrieshave had with past internal subversion con-

ducted with Chhese encouragement and sup-

port. Establishment of diplomatic relations by

Singapore and Indonesia with the PRC reflectsa lessening in tension and better commercial andtrade ties, but there is a latent worry about Chi-na’s political influence in the region.

Several of the ASEAN states view the largeVietnamese army as a possible threat and havemaintained a more or less cohesive ASEAN

stance toward Vietnam. Thailand has been themost concerned with the military threat fromVietnam and is more closely tied to China thanthe other ASEAN countries. The Thai gover-nment has taken the lead in formulating a newapproach that views the Indochina countriesas potential economic partners rather thanmilitary foes.

Indonesia has the closest relationship of the

ASEAN countries with Vietnam and would like

Viemam to establish itself as a usefil buffer be-tween China and the rest of Southeast Asia. Inthe Indonesian view, Vlemam does not pose athreat to others in the region. Balancing thatpoint, Indonesia also sees Vietnam as a strongand potentially powerfhl regional actor. Theywould prefer to see both ASEAN and US poli-

cies designed to lessen CIS influence in Vietnam

and encourage Vietnam to modifi its command

economy and political outlook to permit effec-

tive national development and a more moderatepolitical posture.

The ebb and flow of history plays a role in re-gional threat perceptions. The communist coup

56 February 1993. MILITARY REVIEW

SE ASIA DEVELOPMENTS

attempt in Indonesia in 1965 and the long com-munist insurgency in Malaysia color those coun-tries’ view of the threat today. Vietnam, with amillennium of struggle against China, remainssuspicious of that country despite Chinese assis-tance in Vietnam’s successful wars with France

and the United States and despite recent nor-malization of relations between the Vietnam andthe PRC. Conflicting claims to the Spratly and

Paracel islands remain a source of potentiallydestabilizing cofiontation.

Although China has assured the region’s gov-ernments that it no longer supports subversiveactivities directed against their specific coun-tries, such assurances are taken with a grain ofsalt. It is di~lcult for them to differentiate be-tween party-sponsored and state-supported sub-

version.The significant enlargement of the naval ca-

pabilities of India and Japan are also of concernto the region. It is diflcult for Southeast Asiancountries occupied during World War 11to forgettheir experiences with Japan. There is con-siderable concern about the new reach of theJapanese Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF).America’s role in urging a greater strategic rolefor the Japanese is matched by assurances toSoutheast Asian friends that no offensive capa-bility to threaten the region is either intended orwould be allowed.

Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore and Malaysiaare concerned about the growth of the Indiannavy. Those Indian Ocean littoral countries eyewith suspicion the expansion of Indian military

facilities in the Andaman Islands and questionthe need for an apparently expansionist offen-sive capability in India’s historically inward–looking, ground-based forces.

More immediately, a plethora of overlappingterritorial claims in the South China Sea posethe most serious near-term threat to stability.Various claims to tiny, barren, but potentially

oil–rich specks of land in the Spratly Islands,nearby reek and the region north of Indonesia’s

Natuna Island involve the PRC, Vietnam, thePhilippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. Hopefully,these competing claims car-t be settled by nego-

Vietnam dkpkbys a significantpercentage of its best combat units to

defend its border with the PRC and toprovkie security for Hanoi, Haiphong

and Ho Chi Minh City. As much as 50percent of the army is dkployed in those

critical assignments. Units sta.tiunedalong the Chinese bordkr are considered

to be the best. . . in the army.

tiations that recognize territorial claims, aswell as provide for economic zones that giveeach litigant a chance for exploiting the lands’natuml wealth.

Regional Military ForcesSoutheast Asian military forces share several

points in common, All are modernizing theirequipment and major weapon systems withinlimits imposed by tight budgetary constraints.They are acquiring new weapon systems from avariety of outside sources. Logistic and mainte -nance problems loom large. Most are making

MILITARY REVIEW . February 1993 57

progress in developing domestic defense indus-

trial capabilities. Each has had to contencl with

a clifferent set of circumstances impelled hy a

range of domest ic policies and priorities.

While all ASEAN countries are buying newsystems, the emphasis is on gaining competencein new technology rather than on racing to keep

up with potentially threatening neighbors. All

are striving for increased professionalism and

technical capability and—particularly after the

dramatic events in Thailand-tend to play a

lesser role politically than in the past. A look at

four of the regional military establishments illus-

trates the nature of current developments.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam. TheSocialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) maintains

one of the largest armies in the world, one that

is far larger than any realistic appraisal of the

country’s defense needs would require. Whilehindered by the country’s dire economic prob-lems, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) is

strong, well armed and well disciplined. Its

equipment comes fiwrn domestic production, aswell as outside sources including the old Sovietand Chinese equipment and a variety of USweapons recovered afier 1975. Foreign equip-ment is kept operational by lo-cally manufactured spare parts,as well as those purchased onworld markets. However, each

year the amount of such equip-ment that is operationally us-able decreases.

Vlemam deploys a significantpercentage of its best cornhatunits to defend its border withthe PRC and to provide securityfor Hanoi, Haiphong and HoChi Minh City. As much as 50percent of the army is deployed

known with certainty. The withdrawal fromCambodia has returned over 100,000 men toVietnam. The number of troops in Laos has been

drastically reduced as well. Vietnamese strategyis to retain as much influence in Cambodia andLaos as UN policies and internal factionalsquabbling will allow. In Laos, the Vietnamesewant a nominally independent governmentclosely tied to them through “advisen” and vi-able economic and political ties.

There are over 2,500 Russian “advisers” and

technicians in Vietnam now, although thosenumbers are in decline as the Russian presencein the Pacific is reduced. Russian force deploy-ments to Cam Ranh Bay have decreased signifi-cantly fi-om levels of the mid– 1980s. However,the facility remains available for use by Russianforces. In return fhr access to Vietnamese basesand as part of its commitment under the Soviet-Vietnamese Treaty of Friendship, Russia pro-vides significant military and economic assis-

tance to Vietnam and Laos.Since 1975, the Soviet Union and its succes-

sor government have provided over $6 billion inarms aid to Vietnam and an additional $9 billionin economic assistance. The magnitude of

in those critical assignments. [Indonesia] maintnins the hugest armed forcesUnits stationed along the Chi- ef the non-communist states in the region. However,nese border are considered to be since 1985, Indonesia has signi~antly reorganizedthe best tactical units in the and streamlined its force structure and completed aarmy. changeover to a new, younger generation

The number of Vietnamese of military leadership.troops deployed abroad is not

58 February 1993 � MILITARY REVIEW

changes and the significant so-cial, p(>litical and economicpressures inside Russia make itclear that this level of assistancewill decline dramatically. Thismakes it important f(>rVietnamt~~ find new s~~urces of assis-tance for eccmomic develop-ment, and it probably signals adecline in the size of the potentVietnamese militax-y establish-ment.

The possibility of a UN-bro-kered settlement in Cambodiaand the probability that Viet-nam will finally mm’e to settlethe emoti(mal US POW/MIAissue makes it probable thatVietnam will he able to makemajor shifts in its internationalpolitical and ec~m(~mic relati(ms

SE ASIA DEVELOPMENTS

The new Indian corvette /NS WNJti. +

The significant enkugement of the navalcapabilities of India and Japan am also of concern to

the region. It is di~cult for Southeast Asiun countn”esoccupied dum”ngWorld War II to forget their

experiences with Japan. There ii considerable concernabout the new reach of the Japanese Ground

Self-Defense Force.

in the near term. Ntmnalizati(m of relationswith the United States seems m~w a matter ~~f“when, m~t if.” The ec(mt~mic and political im-plicat i(ms ~Jfmmnalizat i(m are (lf major imp~~r-tance t(> Vietnam and to its regional neighkx~rs.The new economic and trade implicati(ms f~lrthe region are significant, with most countriespositi(x-ting themselves f~~r the advantages that~,ill Cc>me \\,ith increa=~cj world trade and inl,est.

ment in Vietnam.

Indonesia. Inckmesia, the fourth largestcountry in population in the w(~rlcland the moststrategically k~cated ~~fthe ASEAN ccwntries,maintains the largest armed forces of the n(m-comrnunist states in the region. However, since1985, Indonesia has significantly reorganizedand streamlined its force structure and com-pleted a change(wer to a new, younger genera-tion of military leadership.

The army emphasizes two types of fbt-ces re-ferred to in Indonesian doctrine as the territorialforce and the tactical force. A majority of thearmy’s personnel strength is assigned to the geo-graphically oriented territorial fbrce. The largestformation are the 10 powerkl Military RegionalGJmmands, commanded by army major gener-als. In 1985, the number of these commands was

reduced from 16 to 10. The air f(>rce and navyhave also streamlined their headquarters andoperational commands.

The net result is a somewhat smaller armedforce with a compartmentecl defense system inwhich the principal component is the major is-land or island group. During an emergency, thearmy commander in a threatened area will takecommand (>fall forces in the region, coordinat-ing air and naval activities through service liai-son oflcers (m his staff. The navy and air forcewould provide tact ical support (air–to-ground~wnnery and bombing), strategic support (airand sealift ), as well as forward defense support(patrolling and interdiction of invading forces).The army has adopted low-intensity conflict asits primary tactical doctrine.

The reorganization did not neglect the tacti-cal f(x-ce. The Army Strategic Reserve Com-mand (Kosmad) was designated as the tacticalforce of the army. It was reorganized into two in-fantry divisions, both based on Java, and a sepa-rate brigade on Sulawesi. All Kostrad units haveboth ait+wrne and standard infantry capabilities.A Kostrad quick reaction force is capable of rapidmovement to any area of the country on shortnotice. The army’s Red Berets, redesignated as

MILITARY REVIEW � February 1993 59

the Special Forces Command, retain their tradi-tional missions resembling those of the familiarUS Army Green Berets.

Of greater significance than reorganization isthe regeneration of the armed forces leadership.A major generational change was completed in

The domestic political situationin the Philippines remains problematic.. . . US withdrawal from its bases there

ushered in a new era of secun”tyrehzti”onships in the region. The new

world politi”cal order enables the UnitedStates to maintain its forward-deployedsecum”typresence in the region without

permanent bases in the region.

1986 when officers of the “Generation of 1945”

retired from act ive duty. The armed forces arenow led by officers who graduated from the Indo-nesian military academy system afier 1959. Thistransferred leadership to a new breed of oflcermolded from a post–independence civil andmilitary education system. These oflcers areprofessionally skilled in military science andmanagement techniques but are somewhat less

sophisticated in international affairs and world

politics than some of their predecessors.Indonesia has been slowly modernizing its

military equipment. Unique among developingnations, the Indonesian armed forces have lowpriority for knding in the national developmentplan, and armed forces acquisitions have slowedin recent years. The most recent major acquisi-tion was the F–1 6 aircraft, matching Thailandand Singap-e as its prima~ fighter force. The

navy has refhbished its US+rigin destroyers

and has purchased a variety of fast patrol craksfrom South Korea, as well as other ships fromGreat Britain, the Netherlands and Germany.

Indonesia zealously guards its nonaligned pos-ture. Reflecting the confidence its economicmodernization has brought, its leadershipstresses a more active foreign policy, and thecountry has increased its visibility on a number

of international issues. The most important toits ASEAN partners has been its strong advoca-

cy and leadership on the Cambodia issue. Cur-rently, there is no major external threat to In-donesia, whose geography isolates it frompotential dangers on the Asian mainland. In1992, Indonesia became the chairman of theNonaligned Movement (NAM) and PresidentSoeharto wants to take the NAM away fromconfiontational east-west politics to emphasizethe need for a meaningful north-south partner-ship for economic development.

Thailand. Thailand’s recent history hasbeen marred by violence in both the domesticand international arenas. The tragic violence ofits army firing on its own people was followed bydramatic political change, and the historic abil-ity of the Thai people to “bend like the bamboo”has enabled the country to emerge horn its trau-ma with a new spirit of civil–military coopera-

tion under an elected civilian government.In recent years, Thailand has also experienced

armed clashes with both Vietnamese and bo-tian forces on its borders and a tense frontier withBurma. Though the threat to Thailand is nowreduced, the country must contend with oftenfractious relations with the Laos army and withethnic and ideological separatists in Burmawhose conflicts ofien spill across their long bor-

der. The end of the Thai communist insurgencyin the 1980s, and the end of disruptive Malay-sian Communist Party activity and Muslim sepa-ratist operations along its border with Malaysiahave removed a major irritant, although bandit-ry remains a problem in the south.

Thailand has been particularly anxious to re-solve the threat from Vietnamese forces in Cam-

bodia and has taken a lead role in seeking to es-tablish a new relationship with Vietnam basedon economic and market ties and a more openpolitical association. Withdrawal of Vietnameseforces calmed the volatile Cambodian border sit-uation and reduced the threat on Thailand’seastern border. But until a lasting peacefid settle-ment has been reached among the fact ions in-side Cambodia, the southeastern border regionwill remain unstable.

60 February 1993 � MILITARY REVIEW

SE ASIA DEVELOPMENTS

Thailand has tailored its armed ftx-ces to con-front two widely differing threats. Infam-y-heavy forces stressing small-unit jungle warfmeand the Border Patrol Police guard frtmtiers withBurma, Malaysia, Laos and Camhxilia. More

heavily armed units, including substantial ar-mored forces all backed by field artillery, areprepared to engage more substantial threats.

Recent maj~x purchases (>fChinese arm~r andaircraft at “friendship prices” have lmmght thePRC and Thailand closer together. But similarChinese sales to Burma make it inevitable thatthe ruthless Burmese government will increasethe let’el t>fits attacks against auton(}my-seekingethnic groups akmg the Thai Ixmler and perhapsrclise h(der tensions again.

Republic of the Philippines. The domesticp>litical situati(m in the Philippines remainsproblematic. The m(>st (~bvi(xls changes havebeen a result of the changed p(ditical and mili-tary associati~m with the United States. USw’ithdrmval fr~m its bases there ushered in a newera of securiv relatitmships in the regi(m. The

new’ w’orld p~~litical order enables the UnitedStates t~~ma’intain its f(wward-deployed security

presence in the regi(m without permanent baxsin the re.gi(m. Htmw’er, the policy requires con-tinued reliable access to repair, k~gistics and re-plenishment facilities in the regi(m; the lCJSS~~fthe Crmv Valley aerial gynnery range used bysmwal ASEAN countries besides the UnitedStates makes unilateral and bilateral training

considerably more costly. Given the pllit ical~datility c~fthe Philippines and the change inthe level t~f the American commitment there,the capahiliw of the NewT Armed F(~rces t~f thePhilippines (NAFP) to re.i+ain c(~hesi~wness andeffecti~wly ccmhat communist insurgency is c>fparwmwnt interest.

Since the Philippine reicktion of Felxuary1986, the r(k of the military in Philippine sc~ci-

ety and politics has changed dramatically. Oncevilified ftx- its support of the late President Ferdi-nand Marc~>s and criticized ftn- Nditicized ctm-ruption, the armed f~~rcesregained ctmsiderablepublic fawn- by their support for gtwernmentalchange and “ptx>ple p(ww-” that lmmght Presi -

The tragic violence of ~hailand’s]armyfiring on its own people wasfollowed

by dramatic political change, and thehistoric ability of the Thai people to “bendlike the bamboo” has enabled the country

to emergefrom its trauma with a newspin”tof civil-militury cooperti”on under

an elected civilian government.

dent Ctmaztm Aquino to power. Since then, re-

peated ccmp attempts by varicws factions of themilitary undermined public regard for the mili -ta~ and caused an endless challenge for the frag-ile central government. Election of retired Gen-eral Fidel Ramos tt~ the presidency provides thechance fc~r fun&mental political and militaryrapprt}chement in the Philippines, but it remainst~~he seen if this historically fractious ctmntry

can cwercorne a seemingly imp~ssible obstacle tt~fiscal and political stability.

The strength t}f the Ct}mmunist Party of thePhilippines (CPP) and its New People’s Army(N PA) insurgency c(mtinues to pose a chal-lenge t~~the g(~vernment. The Mom National

MILITARY REVIEW � February 1993 61

Liberation Front (MNLF) and other separatistmovements in the Moslem southern part ofthe country are experiencing a resurgence inactivity. The NAFP is not capable of simulta-neously’ waging effective operations againstthese multiple threats.

The NPA has remained strong despite lossesafier the departure of Marcos in 1986 and the po-litical buffeting it has faced since then. The

While ASEAN is not, and inall likelihood will not become, a defensepact, ASEAN solidarity has served its

members well. The 1992 ASEANsummit meeting in Manila devoted un-

precedented attentibn to regionul securityissues. . . . Bilateral miltiry cooperation

[remains likely but]. . . a change inthe level of security cooperation appears

inevitable. . . . Most countries havestepped up regional bilizteral training

and exercties.

NPA remains well armed and is capable of ctm-

clucting effective operations against the go\’ern-

ment t-hroughout ~he c(wntry. In addition, the

CPP and NPA have th(msands of part--timenoncombatant supporters. Fact i(ms within theNPA ha~’e fractured the m(nernent. Nevmthe-

Iess, it retains a f&midahle capability for tmr(wistactiy’ity to destabilize the government.

The armed forces are hampered by w(wfully1(NVlevels of finding and inadequate logistics

and maintenance support systems. An increase

in US security assistance finds might improve

the situation and m(n’e t(nvard estahlishmtmt ofa professi(mally capable armed force that can tru-ly “move, shm)t and c(mununicate” effecti~ely.

The NAFP has the desire to become self–reliantand to defeat the insurgent ies. However at pres-ent, the NAFP could not repel a major externalinvasi(m of its tmrit(wy and could not cope effec -

tively with concentrated armed opposition from

h)th the NPA and the MNLF

The Role of ASEANIt is indeed fortunate that the strategic im-

portance of the Stmth China Sea regitm and the

political change affecting the c~mntries therehas not translated into disharmony within theregion. Stability in the regi(m is due, in largepart, to the solidifying role of ASEAN and thedetermination of its members to maintain this

stability.

While ASEAN is not, and in all Iikelih(xd

will not become, a defense pact, ASEAN soli-

darity has served its members well. The 1992ASEAN summit meeting in Manila Clew)ted un-precedented attention to regi(mal security issues.Though it is not likely there will be any changefrom ASEAN members’ policy of bilateralmilita~ c(x)perat ion rather than a multilateral

security pact, a change in the level of security

c(x)perati(m appears inevitable. Military mod-

emizati~m, as well as milita~ and p(ditical c(m-sultati(m have brought a more comm(m under-standing of the nature of the internal and

external threats t( J the regi(m, as well as a keen

realizati(m of the benefits that can accruethr(wgh c(x)perative m(xlcmizati(m.

While rhe military forces of ASEAN havesought new equipment from a ~rariety of xmrces,

there is c(msiclerahlc parallelism in acquisiti~m of

major wcap(m systems. This facilitates stan&rd-izati(m and intm)perability, advantages the vari -OUS count rim are experiencing as they c(mductincreasing y frequent bilateral military c(msulta -ti(ms, training and exercises. It is of great helpin Iogist ic and operational C(X)pemt ion.

Military cooperati(m is a major comp(ment of

the ASEAN partnership. Although no member

adv(u]tes establishment of f(mnal multilateral

military ties, the countries arc tied to each otherby a web of bilateral programs that permit each

country to become familiar with the operationalcapabilities and procedures of the others. Manyc(x)perative programs have been in place foryears. Indonesia’s bilateral exercises with Malay-sia, Sin#dpore and Thailand, tx)rder meetings

between Indonesian and the Philippines and be-

tween Indonesian and Malaysia, and Thailand’s

62 February 1993 � MILITARY REVIEW

SE ASIA DEVELOPMENTS

cooperation with Malaysia in counterinsurgencyoperations along their common border are ex-amples of the bilateral military cooperation thathas strengthened the region. The newest formal

agreement between Singapore and Indonesia

provides for joint use of aerial and air–to-ground

ranges in Sumatra. These programs are likely to

continue for the foreseeable future, bringing

benefits to all concerned.The reduction in presence of superpower

forces in the region has also brought the realiza-

tion that increased regional military cooperationis essential. Most countries have stepped up re-

gional bilateral training and exercises. For exam-

ple, in August 1991, Indonesia and Malaysia

conducted their first major tri–service combinedtraining exercise, which is likely to become anannual event. Tough political issues still remain.Malaysia and Singapore squabble peri(~dicallyover military and security issues. This was illus-trated by Singapore’s publicized irritation thatthe training exercise was conducted tcm close to

Singapore and that it coincided with Singapore’s

National Day.

Indonesia’s armed forces’ Commander in

Chief, General Tiy Sutrisno, likened the region-al security process to that of a spider web. Eachlink of the web ties together two elements of themultinational ASEAN partnership, as well asother friendly regional countries such as the

United States, Australia, New Zealand and the

United Kingdom. The web as a whole, repre-

senting political, economic, trade and security

ties and strengthened by the sum of its parts, pro-vides a viable security net for the entire SouthChina Sea region.

ASEAN leaders increasingly see Americanmilitary presence in the region as a key elementin both unilateral and regional security policies.

ASEAN leaders increasinglysee American military presence in the

region as a key element in both unilateraland regional secun”ty policies.

No longer viewed in a “winllbse’’politicalframework, American forces are seen as

a viable secun”ty asset that beneftis allregional countn”es without bm”nging

intrusive great power polih”cal-militarycompetition to bear on the countn”es

of the region.

No longer viewed in a “win/lose” political fi-ame-

work, American forces are seen as a viable se-curity asset that benefits all regional countries

without bringing intrusive great power political-military competition to bear on the countries ofthe region. Nonalignment, however, makes itdifficult for some ASEAN countries publicly tosupport a US presence. US military access in the

region will be discreet and is likely to consist of

increased visits to existing military facilities rath-

er than establishment of new US bases or basing

rights in the region,Thus, the countries of South China Sea basin

have witnessed great changes in superpowerrelations, as well as gained in their own self–confidence. In this strategically important area,

during a time of continued tensions, the coun-tries of the region have mken advantage of rela-

tive stability and economic prosperity and devel-

opment to improve the professional character of

their own armed forces. While each nation facesunique circumstances in the modernization andprofessionalization processes, all are meeting keychallenges with a firm sense of their individual

and collective security rcdes in the region. MR

CobnelJohn B. Hawnan isulith the Defm.wand Army AttA& at the AmericanEmbassy inJakarta, hdunesia. He receiveda BA. from the Unitcrsity of Missouri,an M.P.A, from the Unitwsity of Kansa and an M. M.A. S. from the US ArmyCommand and General Sta$ CJkge (USACGSC). He [s a graduate of theLNACGSC, the School of Ad~lanccdMdmry Studiesand the Army War C(dlqe.He k a frequent conm”bucorto Militaty Ra’iew’.

MILITARY REVIEW � February 1993 63