Song and Dance Music in the Middle Ages

-

Upload

musicatwork -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Song and Dance Music in the Middle Ages

Song and Dance Music in the Middle Ages (Chapter 4)

OutlineI. European Society, 800-1300

A. Secular traditions 1. Outside the church, few people could read music. 2. Secular music was rarely written down. 3. Surviving evidence of secular music

a. Several hundred monophonic songs b. Many poems sung to melodies now lost c. A few dance tunes d. Descriptions of music-making e. Pictures of musicians playing various instruments f. A few instruments

4. Songs and dances reflect medieval society and establish traits common in European music ever since

B. Successors to the Roman Empire 1. The Byzantine Empire comprised Asia Minor and southeastern

Europe. 2. The Arab world was the strongest.

a. Began to expand after the founding of Islam (around 610) b. Occupied a vast territory, from modern-day Pakistan to

North Africa, and Spain. 3. Western Europe

a. Weakest, poorest, most fragmented of the three b. Charlemagne's coronation as emperor marked an assertion

of continuity with the Roman past. 4. Byzantine and Arab contributions to western Europe's culture

a. Byzantines preserved Greek and Roman science, architecture, and culture.

b. Arabs extended Greek philosophy and science. c. Arab rulers were patrons of the arts, inspiring Charlemagne

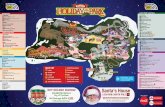

to support intellectual and cultural life. C. Emerging countries of modern Europe (see HWM Figure 4.1)

1. France, the western part of the empire a. The French king was weak until about 1200. b. This allowed numerous strong courts to develop, some of

which nurtured the development of secular music. 2. Holy Roman Empire, the eastern part of the empire

a. German kings claimed the title of emperor as Charlemagne's successors.

b. Their empire included non-German lands as well, from the Netherlands to northern Italy.

c. Regional nobility had considerable autonomy and competed for prestige by hiring the best musicians.

3. England developed a centralized kingdom.

4. Italy remained fragmented among several rulers, including the pope.

5. Spain was divided between Christian kingÂdoms in the north and Muslim lands in the south.

6. Crusades a. Series of campaigns between 1095 and 1270 to retake

Jerusalem from the Turks b. Although they failed, the Crusades showed the growing

confidence and military power of western Europe. D. Society in western Europe

1. Western Europe saw remarkable economic growth. 2. The economy was largely agricultural. 3. Most people lived in rural areas. 4. There were three broad classes (see HWM Figure 4.2).

a. Nobility, including knights, controlled the land and fought wars.

b. Clergy, including priests, monks, and nuns, were devoted to a religious life.

c. Peasants, the majority of the population, worked the land and served the nobles.

5. The growth of cities a. By 1300, several cities had populations over 100,000. b. Artisans in cities organized themselves into groups called

guilds to regulate their crafts and protect their interests. c. Doctors, lawyers, merchants, and artisans formed the new

middle class. 6. Learning and the arts thrived.

a. Cathedral schools were established throughout Europe from 1050 to 1300.

b. After 1200, independent schools for laymen spread as well. c. Universities were founded in Bologna, Paris, Oxford, and

other cities. d. Works of Aristotle and other writers were translated from

Greek and Arabic into Latin (the language of scholarship). e. Scholars such as Roger Bacon and St. Thomas Aquinas

made new contributions to science and philosophy. f. Poems in Latin and vernacular languages, many of which

were sung, diverged from ancient models. II. Latin and Vernacular Song

A. Songs in Latin 1. Versus (pl. versus)

a. Sacred song, sometimes attached to the liturgy b. Rhymed poetry, usually with a regular pattern of accents c. Monophonic versus appeared in Aquitaine in southwestern

France in the eleventh century. d. The music was newly composed, not adapted from chant.

2. Conductus (pl. conductus) a. Similar to versus, with original music and rhymed,

rhythmical texts in Latin b. Originated in the twelfth century c. Original function was to "conduct" a celebrant or a

liturgical book from one location to another during the liturgy.

d. The term was later used for any serious Latin song with a rhymed, rhythmical text regardless of the subject.

3. Latin secular songs a. Educated people spoke and understood Latin. b. Latin songs treated nonreligious subjects, including settings

of ancient poetry and laments, and were often satirical, moralizing, or amorous.

c. The little music that has survived is not notated clearly enough to be transcribed.

4. Goliard songs a. Composed in the late tenth through thirteenth centuries by

wandering students and clerics b. Texts are in Latin. c. Topics include religious themes, satire, and celebration of

earthly pleasures such as eating and drinking. B. Vernacular song

1. There are almost no descriptions or examples of the music of the peasants.

2. A few street cries and folk songs have been preserved through their quotation in music intended for educated audiences.

3. Chanson de geste ("song of deeds") a. Epics in northern French vernacular b. Celebrated deeds of national heroes c. The most famous chanson de geste is Song of Roland (ca.

1100), about a battle between Charlemagne's army and Muslims in Spain.

d. Little of the music has survived. 4. Epics from other countries, including England's Beowulf (eighth

century), the Norse eddas (ca. 800-1200), and the German Song of the Nibelungs (thirteenth century), were likely sung, but the music was not written down.

C. Professional musicians 1. Few records survive to document the professional musicians of the

Middle Ages. 2. Bards in Celtic lands sang epics at banquets, accompanying

themselves on harp or fiddle. 3. Jongleurs (see HWM Figure 4.3)

a. Traveling entertainers who told stories and performed tricks in addition to performing music

b. The word jongleur comes from the same root as the English word "juggler."

4. Minstrel (from the Latin minister, "servant") a. By the thirteenth century, the term meant any specialized

musician. b. Many were highly paid, unlike the jongleurs. c. They were on the payrolls of courts and cities. d. They came from many economic backgrounds.

III. Troubadour and Trouvère Song A. French aristocrats cultivated courtly song composed by poet-composers in

two vernacular languages (see HWM Figure 4.4). 1. In the southern region, the language was Occitan and the poet-

composers were called troubadours. 2. In the northern region, the language was Old French and the poet-

composers were called trouvères. 3. The two languages were also named for their words for "yes."

a. Occitan was langue d'oc, the language of "oc" for yes. b. Old French was langue d'oïl, in which "yes" was oïl

(pronounced like present-day oui). 4. The root words trobar and trover meant "to compose a song," and

later "to invent" or "to find." 5. Female troubadours were called trobairitz.

B. Troubadours and trouvères came from many backgrounds. 1. Their biographies, called vidas, were written down and many

survive. 2. Some were members of the nobility, e.g., Guillaume IX, duke of

Aquitaine (1071-1126), and the Countess of Dia (fl. late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries).

3. Some were born to servants at court, e.g., Bernart de Ventadorn (ca. 1130-ca. 1200), shown in HWM Figure 4.5.

4. Others were accepted into aristocratic circles because of their accomplishments and demeanor, despite their middle-class roots.

5. Some performed their own music; others entrusted their music to a jongleur or minstrel.

C. Surviving songs 1. The songs were preserved in chansonniers (songbooks). 2. Troubadour songs

a. About 2,600 survive. b. Only one-tenth survive with melodies.

3. Trouvère songs a. About 2,100 survive. b. Two-thirds survive with melodies.

4. When songs were copied into more than one chansonnier, there are differences, indicating oral transmission before the songs were written down.

D. Poetry

1. The poems of the troubadours and trouvères were the finest of Western vernacular poetry at the time.

2. Poems are notable for their refinement, elegance, and intricacy. 3. Subjects

a. Love songs predominate. b. Other types: political, moral, and literary topics, dramatic

ballads and dialogues, and dance songs 4. Forms

a. Most poems are strophic. b. Dance songs often include a refrain—a recurring phrase or

verse with music usually sung by dancers. 5. There are several genres, such as the alba (dawn-song), canso (love

song), and tenso (debate-song) of the troubadours. E. The central theme was fin' amors (Occitan) or fine amour (French)

1. Translated as "courtly love" or, more precisely, "refined love" 2. Love from a distance, with respect and humility 3. The object was a real woman, usually another man's wife. 4. The woman was unattainable, making unrewarded yearning a

major theme (e.g., NAWM 8, Can vei la lauzeta mover by Bernart de Ventadorn).

5. The artistry of the poems demonstrates the poets' refinement and eloquence.

6. When women wrote poetry, their poems seem more direct and realistic (e.g., HWM Example 4.1 and NAWM 9, A chantar by the Countess of Dia).

F. Melodies 1. Strophic, with every stanza being set to the same melody 2. Text-setting is syllabic with occasional groups of notes, especially

on a line's penultimate syllable. 3. Range is narrow, within a ninth. 4. Melodies move primarily stepwise. 5. Modal theory was not part of the composers' thinking, yet most

melodies fit the theory, with the first and seventh modes being most common.

6. Form (see HWM 4.6) a. Most troubadour melodies have new music for each phrase. b. AAB form is common in trouvère melodies and was used

by some troubadours as well (e.g., A chantar). 7. A chantar

a. Seven-line stanzas b. The form is AAB, with each section ending with the same

melody (a musical rhyme). c. At the level of the phrase, the form is ab ab cdb, with "b"

being the musical rhyme. d. Stepwise motion within an octave range

e. Suggests model with high points on the note A and cadences on D

8. Rhythm is usually not notated. a. Some scholars believe melodies were sung with each

syllable receiving the same duration. b. Other scholars believe the songs were sung with a meter

corresponding to the meter of the poetry. c. Dance songs were mostly likely sung metrically, and

elevated love songs may have been sung more freely. d. Modern editions will vary because of competing views.

G. Musical plays 1. Musical plays were built around narrative pastoral songs. 2. The most famous was Jeu de Robin et de Marion (The Play of

Robin and Marion, ca. 1284) by Adam de la Halle (NAWM 10). 3. Adam de la Halle (ca. 1240-1288)

a. The last great trouvère b. Depicted in HWM Figure 4.7 c. His complete works were collected into a manuscript,

which indicates he was held in high esteem. 4. Robin m'aime (NAWM 10) is a rondeau.

a. Dance song with a refrain b. Form is ABaabAB (capital letters indicate the refrain). c. Another setting is polyphonic and notated in precise

durations, indicating a metrical rhythm. H. Rise and fall of troubadour tradition

1. Its origins include three possible genres. a. Arabic songs b. Versus c. Secular Latin songs

2. Albigensian Crusade, declared by Pope Innocent III in 1208, destroyed the culture and courts of southern France.

3. Troubadours dispersed, spreading their influence to neighboring lands.

IV. Song in Other Lands A. England

1. Songs in French a. French was the language of the kings and nobility in

England. b. The English king held lands in France and participated in

French politics and culture. c. King Richard I (the Lionhearted, 1157-1199) was a

trouvère and wrote songs in French. 2. Songs in Middle English

a. The lower classes spoke Middle English. b. Few melodies survive for songs in Middle English.

c. Surviving poems in Middle English were meant to be sung and suggest a rich musical life.

B. Minnesinger 1. Knightly poet-musicians who wrote in Middle High German 2. They were modeled on the troubadours. 3. Flourished between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries 4. They sang Minnelieder (love songs) emphasizing faithfulness,

duty, and service in the knightly tradition. 5. The songs are strophic. 6. The most common melodic form is AAB, called bar form.

a. Each A section (Stollen) uses the same poetic meter, rhyme scheme, and melody.

b. The B section (Abgesang) is usually longer and may end with all or the last part of the Stollen.

7. As with the troubadour songs, the rhythmic notation is unclear. 8. Crusade songs were a new genre with the Minnesingers.

a. Songs about experiences of crusaders who renounced worldly comforts to travel on Crusades.

b. Example: NAWM 11, by Walther von der Vogelweide (ca. 1170-1230), depicted in HWM Figure 4.8.

C. Laude 1. Few secular songs in Italian survive with music from before 1300. 2. Melodies for several dozen laude (sing. lauda) have come down to

us. a. Sacred Italian monophonic songs b. Sung in processions of religious penitents and in gatherings

for prayer c. From the late fourteenth century on, most laude were

polyphonic. D. Cantigas de Santa Maria

1. Over four hundred songs in Gallican-Portuguese in honor of the Virgin Mary

2. King Alfonso el Sabio (The Wise) of Castile and Léon in northwest Spain directed the compilation of these songs in about 1270-1290.

3. Four beautifully illuminated manuscripts preserve these songs. 4. Most songs described miracles performed by the Virgin.

a. Mary had been venerated since the twelfth century. b. NAWM 12 describes how Mary caused a piece of stolen

meat to jump about, revealing where it was hidden. 5. The songs all have refrains.

a. In performance, a group singing the refrains could have alternated with a soloist singing the verses.

b. Songs with refrains were often associated with dancing, as shown in some of the illustrations in the Cantigas manuscripts.

6. Most verses are in AAB form. a. The music of the B section is also used for the refrain. b. Because the refrain appears first, the musical form is

written: A bba A bba . . . A. V. Medieval Instruments

A. Illustrated manuscripts often depicted instruments, although the music notation did not offer any indication of instrumental participation.

B. Europeans adapted instruments brought from the Byzantine Empire or from the Arabs in North Africa and Spain.

C. String instruments (see HWM Figure 4.9) 1. Vielle (fiddle)

a. The principle medieval bowed instrument b. Predecessor of the Renaissance viol and modern violin c. Five strings tuned in fourths and fifths, with one or more

used as a drone 2. Hurdy-gurdy

a. Three-stringed vielle played mechanically with a hand-crank

b. The player depresses levers to change pitches on the melody string.

c. The other two strings are drones. 3. Harp 4. Psaltery

a. The remote ancestor of the harpsichord and piano b. Strings are attached to a frame over a wooden sounding

board. c. The player plucks the strings.

D. Wind and percussion instruments (see HWM Figure 4.10) 1. Flute

a. Transverse flute, similar to the modern flute b. Made from wood or ivory c. No keys, only holes

2. Shawm, a double-reed instrument similar to the oboe 3. Medieval trumpet

a. Straight b. No valves, so it could play only pitches of the harmonic

series 4. Pipe and tabor

a. Left hand fingered a high whistle. b. Right hand beat a small drum with a stick.

5. Bagpipe a. The universal folk instrument b. The pipes and chanter are reed instruments. c. The player inflates a bag, which forces air through the

chanter and drone pipes. 6. Bells were used in church and as signals.

E. Organs 1. Monastic churches had started installing organs by ca. 1100. 2. Organs were common in cathedrals by 1300. 3. Portative organ

a. Small enough to be carried with a strap around the neck b. One set of pipes c. The right hand played the keys while the left worked the

bellows. 4. Positive organ

a. Placed (positum) on a table b. An assistant pumped the bellows as the musician played.

VI. Dance Music A. Songs for dancing: the carole (see HWM Source Reading, page 82)

1. The most popular dance in France from the twelfth through the fourteenth centuries

2. One or more of the dancers sang the song as the others danced in a circle.

3. Instrumentalists also participated. 4. Only about two dozen melodies survive.

B. Instrumental music for dancing 1. About fifty dance tunes survive from the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries. a. Most are notated as monophonic pieces, but several players

could participate. b. Some are set in polyphony for performance on a keyboard

instrument c. These tunes are the earliest surviving notated instrumental

music. d. Features include steady beat, clear meter, repeated sections,

and predictable phrasing. 2. Estampie

a. The most common medieval instrumental dance b. Several sections, each played twice but with different

endings 1. The first ending was open (ouvert), or incomplete. 2. The second ending was closed (clos), or complete. 3. The same open and closed endings were usually

used for all the sections. c. Triple meter d. Estampies from Le manuscrit du roi (The Manuscript of the

King) 1. Includes eight "royal estampies" 2. The fourth is NAWM 13.

3. Istampita a. The fourteenth-century Italian relative of the estampie

b. The same form, with repeating sections, but the sections are longer

c. Meter is duple or compound.

![Song and Dance [Score]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5571f8aa49795991698ddae5/song-and-dance-score.jpg)