Social Modality

-

Upload

muhammad-rachdian -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Social Modality

-

Lund University Cognitive Studies LUCS 35 1994. ISSN 11018453.

LINGUISTIC MODALITY AS EXPRESSIONS

OF SOCIAL POWER

(Revised version)

Simon Winter & Peter GrdenforsLund University Cognitive Science

Kungshuset, LundagrdS222 22 LUND

E-mail: [email protected]@fil.lu.se

Abstract: The semantics of the linguistic modals is argued to be determined mainly by the power structure of the participantsin the interaction. In the deontic uses of the modals, another determining factor is the expectations of the participants attitudestowards the relevant action. By viewing the evidence as a power in its own right, our analysis can be generalized to the epistemicuses in a coherent way. The epistemic uses are seen as pragmatic strengthenings of the deontic uses, rather than as metaphoricalmappings.

INTRODUCTION

It was a warm day. A wasp suddenly came in throughthe car window, irritating the two persons in thefront seat.

Driver: Kill it!Passenger: Must I?D: Well, I cant, since Im driving.P: I dont want to.D: Let it live and get stung, then.

In traditional linguistics, one tends to focus on thel inguistic expressions , which leads to theidentification of grammatical classes. One example isthe class of modal verbs, like must, want to, let andcan, which is traditionally delimited by its syntacticproper t i e s . The conceptual representationsunderlying the linguistic expressions is onlyconsidered as a secondary problem.

Our focus is different: we want to analyze thecognitive functions of modals and their relations toother cognitive functions. This analysis will becoupled with a study of how the linguisticexpressions of the relevant cognitive functions arerelated to other linguistic expressions.1 We will

1Cf. the two approaches outlined in Tomlin (1995):studying how linguistic representations reveal or constrain

argue that the relevant cognitive functionsdetermining modal expressions are interpersonalpower relations and the expectations of the agentsinvolved in the speech situation.

For example, when somebody says I must go now, she2indicates that the listener has some power over her,and that the listener expects her to stay, but there issome other stronger power that forces her to leave.Our aim is to provide a systematic analysis of howdifferent power relations and expectations canaccount for the conceptual structures underlying thesemantics of modal expressions.

This is an example of what is called the deontic use ofmodals, where the powers are situated in the actualspeech situation. Linguists have traditionally alsopointed to what they call epistemic uses of the samemodal verbs, where the necessity or possibility of theproposition is concerned rather than obligations orpermissions. A clear epistemic use would be He maybe home by now. There are also well-known sentencesthat can be given two interpretations, like He must behome now, where the (apparent) ambiguity is made

conceptual representations, versus studying how conceptualrepresentations are mapped into linguistic representations.2In this paper, he means she unless the converse ismore natural. Similarly, she means he, with the sameproviso.

-

2clear by the two continuations (a) ...because hismother says so, and (b) ...because the light is on.

Power relations as a mechanism

for the cognitive structuring

of the linguistic modal field

Interpersonal power relations play an important rolein our everyday social interactions. Parents use theirpower over their children, employers over theiremployees, teachers over their pupils, and moresubtly perhaps a wife over her husband.

These power relations are as ubiquitous as they areimplicit: it is very rare to see the subordinateexplicitly challenging the power, although the tacitpower structure is well known to all of us. Thepower structure is constantly being stabilized,confirmed, questioned, and sometimes challengedthrough our interactions. Linguistic utterances areone means to express these relations, as are actions,body language, etc.

If somebody, for example, asks his boss to open thewindow, despite the fact that he could have done ithimself, this challenges the power the boss has as aboss. This power does not explicitly govern theopening of windows, but gives him an overall higherstatus. If he agrees to open the window, he has donemore than that: he has agreed (or at least seemed toagree) to adjust the power structure by creating aprecedent that can be used in further interactions.

The outcome of this negotiation largely depends onthe expressions we use. It is highly unlikely that theboss agrees if we just point with a finger at thewindow, which is perhaps the way he does it, when hewants us to open the window. As will be seen below,there is a large scale of expressions ranging from thisfinger pointing via imperatives to modals andinterrogatives3 to choose from, depending on thedifferent power structures and, of course, dependingon the different speech act situations.

In traditional linguistics, this class of relations fallsamong the pragmatic structures, pertaining to thespeech act situation. As they are not thought of asbeing explicitly encoded in the language, they are notoften studied. The claim of this paper is, however,that the power structure of a speech situation may beproductively studied as being coded by a fairlylimited set of linguistic expressions the modals.

Even in more cognitive approaches (Lakoff, 1987,Langacker, 1987), using image schemata, the linguisticstructures that code power relations have not beenrecognized. The one notable exception is Talmys

3Or whimperatives after Sadock (1970).

(1988) analysis in terms of forces, which will be ourpoint of departure.

At this stage, our main purpose is to show how ananalysis in terms of power, attitudes and expectationscan account for the semantics of the modal field. As aconsequence of this analysis, it will turn out that, byaccepting evidence as a separate power, the so calledepistemic usages of modals can be seen as a systematictransition from the deontic expressions.

Language excerpts in this article will be mainly inEnglish in the methodological part and in Swedish inthe more formal analytic part.

The linguistic modal field

Most earlier linguistic analyses4 have started from amorpho-syntactic recognition of the modalauxiliaries as a relatively closed class. Limiting theanalysis to these surface criteria blocks therecognition of the power field as a determiningsemantic factor.

Palmer (1979) cites the NICE properties:5Negative form with nt (I cant go), Inversion withthe subject. (Must I come?), Code (He can swim andso can she), Emphatic affirmation (He will be there)and adds No -s form for 3rd person singular (*mays),Absence of non-finite forms (No infinitive, past orpresent participle) (*to can, *c a n n i n g ), Nocooccurrence (*He may will come).6

There are thus several morpho-syntactic criteriawhich are traditionally used to define the modalverbs. Since the modals emerge as a homogenous classon these criteria, is difficult to free oneself fromconsidering them, and adopt the cognitive andpragmatic perspective that we prefer. The difficultiesreside in the impossibility of modelling a cognitivesituation independently of the linguistic expressionsassociated with it.

A semantic distinction that has long occupied bothlinguists and philosophers is that between thedeontic and the epistemic uses of modals. Above wegave the apparently ambiguous example He must behome now. Our aim is not primarily to analyzelinguistic expressions, but to go the other way round,i. e. to seek a linguistic production model, where thecognitive structure determines the linguistic struc-ture. Hence, the ambiguity in question causes noproblem for us: the cognitive model never containsthis form of ambiguity.

4E. g. Palmer (1979, 1986).5These are the English modal features. Swedish, as well asmany other languages, has a similar but different set.6Some examples added.

-

3Here it is important to notice the interdependence ofthe development of language and the cognitive basis there would be no modal expressions unless therewas something to express. But on the other hand,there are no means of forcing the language to express acertain cognitive function language changes slowlyand requires a collective need. In this perspective, theevolution of the modals from manipulative to deon-tic (syntactically marked as auxiliaries), and furtheron to epistemic uses is not trivial (cf. Traugott 1989).In our analysis, we will in particular focus on thislast change, from deontic to epistemic, and what isneeded for a language community to accept the epi-stemic uses.

Force dynamics

The major contribution to a cognitive approach to themodal field is Talmys (1988) force dynamics.Talmy recognizes the concept of force in such expres-sions as (1) and (2). He also notices the possibility inlanguage to choose between what he calls force-dynamically neutral expressions and ones that doexhibit force-dynamic patterns, like in (3) and (4).7Forces are furthermore taken as governing thelinguistic causative, extending to notions like letting,hindering, helping, etc.

(1) The ball kept (on) rolling along the green.

(2) John cant go out of the house.(3) He didnt close the door.

(4) He refrained from closing the door.In his analysis, physical forces are seen as morefundamental than the social. By metaphoricalextension, the expressions used to express physicalforces are used in the psychological, social,inferential, discourse, and mental-model domains ofreference and conception (1988:49, the abstract). Hisaim is to complete the list of certain fundamentalnotional categories [that] structure and organizemeaning (p. 51), and he mentions number, aspect,mood and evidentiality.

Talmys dynamic ontology consists of two directedforces of unequal strength, the focal called Ago-nist and the opposing element called Antagonist,each force having an intrinsic tendency towards eitheraction or rest, and a resultant of the force interaction,which is either action or rest.

All of the interrelated factors in any force-dynamic pattern are necessarily copresentwherever that pattern is involved. But a

7Examples from Talmy (1988:52).

sentence expressing that pattern can pick outdifferent subsets of the factors for explicitreference leaving the remainder unmentioned and to these factors it can assign differentsyntactic roles within alternative construc-tions. (p. 61)

One big, mostly methodological, difference betweenour approach and Talmys is that we do not view theprime function of language as describing, but ratheras acting on the world. In this vein, Sweetser(1990:65) writes:

The imposing/reporting contrast has interest-ing parallels with Searles (1979) assertion/declaration distinction; like certain other(rather restricted) domains, modals are an areaof language where speakers can either simplydescribe or actually mold by describing.

The distinction between the acting and the describingfunctions will provide us with a richer structure inthe modal field, as well as a clearly visible connec-tion to other moods, such as the imperative.

Talmys analysis of the English modals starts with arecognition of the modals according to the morpho-syntactic properties discussed above. Talmys aim isto see how the linguistically delimited set of modalscan be analysed in terms of force dynamics. Incontrast, we start out from a semantic representationand expand the set of linguistic expressions codingthis field. However, like we do, he lets the analysiswork backwards, which permits him to extend thevery limited group of traditional modals by someother related verbs, like make, let, have, help, butstill with support from morpho-synctactic proper-ties.8

Power instead of force

In contrast to Talmy, we view social power relationsas semantically fundamental, and physical forces asderived. It is above all our speech act centeredapproach that has led us into the power play ofcognitive agents, and we will argue that the epistemicuse of modals is better understood by viewing thisphenomenon as power rather than forces. We readilyadmit a great influence from Talmys force dynamics,but we have found that the attitudes we discuss, and

8It is difficult to differentiate between the analysis ofTalmy and Sweetser (1990), partly because both Talmyspaper and Sweetsers exist in earlier versions (Talmy 1981and Sweetser 1984) giving them possibility to base theiranalyses on each other. Sweetsers main contribution seemsto be the extension from deontic (root, as she calls it) toepistemic modality (see below). Sweetser (1990) is basedon an earlier work, Sweetser (1984), which is in turn basedon Sweetser (1982). We will throughout only refer to theformer.

-

4above all expectations about these attitudes, are moreadequately accounted for in terms of social powerthan in terms of physical forces.9

POWER RELATIONS AND THEIR

LINGUISTIC EXPRESSIONS

The main justification for our choice of semanticprimitives derives from the fact that language is notautonomous. It is a tool to be used in a social context.The social context is partly determined by the powerrelations between the agents. We believe thatlinguistic modal expressions are primarily expres-sions of such power relations.

The semantics for modal expressions that we willpresent here is fundamentally cognitive. Unlike mostworks in the area of cognitive semantics (Lakoff1987, Langacker 1987), we will not use imageschemas to describe the meanings of modals, but oursemantic primitives will be power relations andexpectations.10 Our goal is to describe a productionmodel for modal expressions, where we start fromcognitive representations of speech situations and usethem to generate prototypical linguistic utterances.

According to our analysis, the central elements of thespeakers and the listeners mental representations arethe social power relations that hold between variousagents. The objects of power are actions, for examplethe action of killing the wasp. I can kill it myself, butif I have power over you, I can also command you todo it. Another important factor of a speech situationis the agents attitudes to the relevant actions.11 Forexample, I may want to kill the wasp, while you maywant that this action not be performed.

Apart from power relations, actions, and attitudes toactions, our semantic model also contains as funda-mental notions different kinds of expectations. Foran analysis of modals, the most important expecta-tions are those that concern the attitudes of otheragents towards the actions that are relevant in aspeech situation. For example, I may not want to killthe wasp while I know that you are my superior. Imust thus consider your attitude towards killing the

9Talmy is not by any means unaware of some of the wideruses of forces/power, and he writes: In addition, FD [forcedynamic] principles can be seen to operate in discourse,preeminently in directing patterns of argumentation, butalso in guiding discourse expectations and their reversal.(Talmy 1988:50)10As will be argued below, image schemas and powerrelations are compatible, and our analysis may well berepresented in a notation similar to Talmys force dynamicschemas.11Attitudes to actions concern the agents preferences , andshould not be confounded with so called propositionalattitudes, e.g. believing or hoping.

wasp. If I dont know it, I must act on my expectationabout your attitude.

Deontic and epistemic uses of

modals

In our semantic analysis, the distinction between thedeontic and the epistemic uses comes out verynaturally as will be seen below.

The general development of meanings in this area canbe illustrated by the following example from Lyons(1982:109), who distinguishes between four stagesfor the example You must be very careful:

(1) You are required to be very careful(deontic, weakly subjective).(2) I require you to be very careful (deontic,strongly subjective).(3) It is obvious from evidence that you arevery careful (epistemic, weakly subjective).(4) I conclude that you are very careful(epistemic, strongly subjective).12

Furthermore, it is quite clear from the analysis thatthe deontic meaning is the primary and the epistemicthe derived one, as is supported by etymologicalevidence. For example, Traugott (1989) writes:

It is for example well known that in thehistory of English the auxiliaries in questionwere once main verbs, and that the deonticmeanings of the modals are older than theepistemic ones.13

Both Sweetser (1990) and Talmy (1988) view theepistemic use of modals as a metaphorical extensionof the deontic use. Calling the deontic use the root-modal meaning, Sweetser says (1990:50):

My proposal is that root-modal meanings areextended to the epistemic domain preciselybecause we generally use the language of theexternal world to apply to the internal mentalworld, which is metaphorically structured asparallel to that external world.

12Here it is interesting to see the importance of the choiceof analytical dimensions. No one has protested against thesubjective dimension presented as continuous, but severalpeople have had difficulties to see the gradual transitionfrom deontic to epistemic, which we have proposed inearlier versions of this paper. In fact, a more productive wayof viewing the subjective dimension is as a contrastunmarked/marked. However, the subjective dimension neednot bother us here, since it has to do with what referents areimplied by the situational context (cf. Grice 1975:567).13See also Sweetser (1990:50).

-

5Our approach is more similar to that of Traugott(1989) who argues that the epistemic use of modalscan be seen as a strengthening of conversational impli-catures. The term implicature is used since Grice(1975), mainly in linguistics and philosophy of lan-guage to mean roughly that which can be concludedfrom the statement and from the context in which itis uttered. We want to view implicature as a kind ofexpectation. The reasons for this are that (1) they arenot normally explicitly stated, (2) they can be used aspremises in reasoning and (3) they are valid untiloverridden by explicit statements or strongerexpectations (cf. Grdenfors 1994).

The expectations generated by conversationalimplicatures will play a crucial role in the transitionfrom the deontic to the epistemic use of modals.When the evidential material contained in the expec-tations is viewed as a power that is detached from thespeakers, it can take the role of a non-negotiablepower. As will be seen below, the diachronicsemantic shifts proposed by Traugott can be ex-plained by a similar externalisation of expectations.

Semantics based on social

interactions

In cognitive semantics, the central notion has beenimage schemas (Langacker 1986, 1987, Lakoff 1987).We believe that our notation yields a satisfactoryanalysis without including the general framework ofimage schemas. However, the two approaches arecompatible, in the sense that image schemas could beextended to model power relations.

Talmy (1988) comes much closer to our analysis withhis force dynamic semantics. In contrast to us,Talmy views the physical force dynamics as the basicand the extension to psychological and socialreferences as metaphorical (1988:69 and 75). Still heremarks that [a] notable semantic characteristic ofthe modals in their basic usage is that they mostlyrefer to an Agonist that is sentient and to aninteraction that is psychosocial, rather than physical,as a quick review can show (1988:79). Wecompletely agree, but see this as an argument for theprimary meaning of the modals being determined bysocial power relations, while the (few) uses ofmodals in the context of physical forces are derivedmeanings. Independently of this argument, Talmysdirected forces are not sufficient for our analysis,since they cannot handle the nested expectations ofthe agents that we will argue are required for aproduction model of modal expressions.

Within the philosophical tradition, earlier analysesof modal expressions have, almost exclusively, beenbased on possible worlds and relations betweenworlds as semantic primitives. Indeed, the firstmodal notions to be analysed were those of necessity

and possibility. There is nothing in the structure ofpossible worlds semantics that is suitable fordescribing social power relations, but such featuresmust be added by more or less ad hoc means.

One notable exception in the philosophical traditionis Prn (1970) who starts out from a sententialoperator Di, where an expression of the form Dip isread as the agent i brings it about that p, where p isa description of a state of affairs. Using this operator,Prn then discusses influence relations (1970, ch.2) of the form DiDjp, which he reads as i exercisescontrol over js doing p (1970:17). However, hefocusses on rights and power relations and onlymarginally discusses the use of this formalism toanalyse modal expressions. Furthermore there is nocorrespondence to our notion of expectations in hisanalysis.

We conclude that neither a cognitive semantics basedon image schemas nor a possible worlds semantics isappropriate for an analysis of the pragmatics ofmodals. Modals are primarily expressions of socialpower relations. We view the meaning of modals asdetermined by their function in the speech actsituations governed by the power relations.

Furthermore, we claim that an analysis of the speechact situations where modals occur cannot becompleted without taking such power relations intoaccount. For example, Talmy (1988) views utterancesin the first or second person involving modals asparallel to sentences in the third person with thesame modals. In contrast, our position is that firstand second person utterances involving modals areprimary since they are speech acts, i.e., moves in alanguage game with the stakes given by the socialrelations that include the assignment of power, whilethird person expressions are secondary reports of suchmoves (cf. Sweetser 1990:65, quoted above).

CENTRAL ELEMENTS OF THE

COGNITIVE STRUCTURE

Actors

The social relations in the speech act analysis that wehave undertaken can be described along twodimensions. The first dimension is the one pertainingto the social power relation, i.e., who has power overwhom. The second is the one defining the roles in thespeech act, i.e., who speaks to whom.

The two primary roles in the power dimension are (1)the one in power and (2) the obedient. The powerrelations manifest themselves by threats (mainlyimplicit) of punishment. We will assume that therelevant relations between the actors are settled forthe speech situation we will be analysing. This is an

-

6idealising assumption, since the language game canchange the relations, but it allows us to study amomentary power structure. We will further discussthe assumption below.

The speech act dimension consists primarily of theroles of the first, second and third person. As will beseen below, the third person role occurs most fre-quently with the epistemic uses of modals. We alsoassume that the speech acts are governed by standardconversational maxims.14

The power dimension and the speech act dimension canbe combined in four different ways. (1) The speaker isthe one in power and the hearer is the obedient. (2)The hearer is the one in power and the speaker is theobedient. (3) The one in power is a third person andthe speaker is the obedient. (4) The one in power is athird person and the hearer is the obedient. In cases (3)and (4), the third person can either be a real person oran impersonal power (cf. Benveniste 1966).15 Theepistemic use of modals involves a special case of suchan impersonal power, namely, the power of the evi-dence. The four cases constitute different cognitivesituations which will generate different linguisticexpressions involving modals. As will be seen below,the connections between modals and the cognitivestructure are surprisingly systematic.

Expectations

Apart from the actors and their power relations, wealso take the expectations of the actors as fundamen-tal elements of the cognitive structure. Winter(1994) argues that a multitude of phenomena withincognitive science can be analysed with the aid ofexpectations. In particular, Grdenfors (1994) showsthat the non-monotonic aspects of everyday reasoningcan be explained in terms of underlying expectations.However, in the history of cognitive science, severalconcepts related to expectations have been proposed,like scripts (Schank & Abelson 1977), frames (Min-sky 1975) and schemas (Rumelhart & McClelland1986)

Expectations are demands in two ways. Firstly, theperson having the expectation has a demand on theexternal world that it conforms to his expectation.

14For example, the cooperative principles of Quantity,Quality, Relation and Manner, proposed by Grice (1975).An example of Relation is the following (ibid.:51) A: I amout of petrol. B: There is a garage round the corner.15Benveniste (1946, 1956, reprinted in 1966) shows thefrequent existence in different languages of a specialmorphology for the third person, which motivates his useof the term non-personne for this function of an actorstanding outside the immediate language game. Since thethird person is not present in the speech act, he will bereferred to in an objective way and, consequently, hispower will not be negotiable. Cf. Benveniste (1966:231;256). Also cf. Austin (1962:63).

The reason for this demand is that he has investedcognitive effort in creating the expectation, and hemay also have built other expectations on it. Second-ly, his investment leads to a demand on himself tocheck with the external world whether his expec-tation is fulfilled. The reason for this is that we actas if our expectations were true, as if unknown valueswere known.

If an expectation is not satisfied, it leads to a conflictfor the person with the expectation. For example,Miss Julie may expect her butler to open the door forher, but he does not. There are two ways out of such aconflict. Either she exercises her power to make theworld conform to her expectation or she changes herexpectation to make it conform to the world. Whichway is chosen depends, at large, on the power of theperson having the expectation.

Linguistic expressions of modality primarily concernchanges of the world, via actions, and thus powerrelations are central. In the case when the expecta-tions are made to conform to the world, one faces acase of an epistemic revision (Grdenfors 1988, 1994).In the latter case, however, the revision is not accom-panied by linguistic utterances since it involves achange of the cognitive state of one agent only.

Expectations about attitudes

The objects of the power relations that we arestudying are the actions that are salient in the speechact situation.16 If the situation consists of twothieves with dynamite in their hand facing a safe, thesalient action is to blast the safe. We assume thatboth the one in power and the obedient are aware ofwhat is the salient action and that the action can beperformed by the obedient. The action can also be anomission (von Wright 1963), i.e., not preventingsomething from happening. For example, if the fusefor the dynamite has been lit, then omittingextinguishing the fuse can be seen as an action, and itcan be the object of modal expressions: Let the fuseburn!

In order that a power relation be effectuated, i.e., thatthe obedient does what the one in power expects, theobedient must know the attitudes of the one in powertowards the salient action. For example, if the obedi-ent knows that the one in power wants the safe to beblasted, he will do so without further ado. If he doesnot know, he must act on his expectations about theseattitudes, or ask the one in power. Such inquiries

16Luckily we have an attention system which prevents usfrom having active attitudes towards all possible actions inour environment. As a matter of fact, it is the attention ofthe one in power that determines the saliency. Consequent-ly, a source of incongruency of the attitudes of the actors iswhen the attention of the obedient is different from that ofthe one in power.

-

7standardly contain modal expressions: Shall I blastthe safe?Even if there is always some form of power relationbetween two agents, these will not result in anylinguistic utterances as long the expectations of theagents are well matched. It is only when the relevantexpectations clash or when they are unknown thatlinguistic communication is necessary to achieve theappropriate actions.

The one in power can, by definition, demand that hisexpectations about the salient action be fulfilled bythe obedient. If his expectation is not fulfilled, thismeans either that the obedient does not know theattitudes of the one in power to the action or that theobedient wants to elude the obligation. The obedientcan, by definition, never demand anything, but possib-ly negotiate with the one in power that he be let offdoing the action.17

We will distinguish between three levels of expecta-tions about attitudes towards an action p. These threelevels seem to distinguish between all occurrences ofmodals that we have found:

(1) The speakers attitude towards p.

(2) The speakers expectation about the hearersattitude towards p.

(3) The speakers expectation about the hearersexpectation about the speakers attitude towards p.

For example, in our paradigm situation (1) I want thesafe to be blasted. (2) I expect that you too want thesafe to be blasted and (3) I expect that you expect meto want the safe to be blasted. Consequently, since Iam the one in power, I expect you to heedfully obey.If you do, this is the idyllic situation where allexpectations are fulfilled. In such a case, nothingneeds to be said, action speaks for itself.

However, if some of the expectations are notfulfilled, the incongruence will normally result insome linguistic utterance from the one whose expec-tation is violated. For example, if I am in power andyou dont want to blast the safe and you expect that Ido not want it, I will then say You must blast thesafe!.

17The participants in a speech situation often have differingperspectives they dont see things the same way.Another aspect of power is that the one in power has theright to impose his perspective on the subordinate. Cf.Andersson (1994).

FORMAL ANALYSIS OF THE

TYPICAL LINGUISTIC

UTTERANCES GENERATED BY

THE COGNITIVE STRUCTURE

Our goal is to show how the cognitive structures ofthe agents in a speech situation can be systematicallyused to generate modal expressions. In other words,we start from speech situations consisting of differ-ent combinations of power and attitudes and predictwhich linguistic utterances typically emerge fromthese situations. The formal analysis containsvariables specifying the action, the actors and theattitudes that the actors have towards the action.

The variables

The action

The action is typically salient in the situation, and thesubordinate person has the ability to perform it. Asour formal system is seen as corresponding to acognitive representation, we have chosen p as standingfor the action, rather than VP and related notationsused in most linguistic contexts. A non-controversialp is then to blow a safe (i.e. non-controversial as a p),shut the TV off, open a window, kill a wasp briefly,everyday simple actions.

Personae

The first, second and third persons, 1, 2, 3, correspondto the normal I, you and the rest. (The plural is notconsidered.)

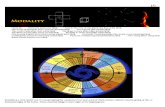

Attitudes toward p

We have elaborated the features designating theattitudes along the lines of Winter (1986) to be ableto account for irrelevance and interrogation states,using + for positive inclination towards p , 0 forindifference relative to p, for a negative attitude and? for a relevant but unknown attitude.18

Basic power patterns

We distinguish between two basic patterns. One inwhich only the speaker and the listener are relevant,and one in which a third actor outside the immediatespeech act situation has an overriding power.

18This ? has caused us some problems. Contrastingexamples like You do want p, dont you? and You dont wantp, do you? show + and hiding behind the question marks.In a more fine-grained analysis, we would thus needattitudes of the form ?+ and ?.

-

8Two actors

When only the two interlocutors are present aspowers, the analysis divides into two asymmetricalcases: (1) when the speaker is the one in power (1 > 2),and (2) when the speaker is the subordinate (1 < 2).The case where the powers are equal does not concernus directly, as our aim has been to methodologicallyenlarge the power differences to be able to analyzethem.

The asymmetry arises, as we will see, due to the rightof the one in power to have her needs satisfied herattitudes are dominant and the subordinates recessivein the sense that recessive here means that they areonly accounted for if the one in power agrees.

Three actors

Earlier analyses (Talmy) have not considered caseswhere more than two (forces or) powers are involved.However, this distinction corresponds to a subgroup-ing among the modal verbs, as will be seen below.

Here, as in the case where we have only two forces, wemake the same distinction between the speaker beingin power (1 > 2, 1 < 3) or not (1 < 2, 1 < 3). The thirdpower is always seen as the strongest. If not, we areback to the cases with two actors.

Analysis

Our aim in this section is to start from the mostfundamental power structure, where the one in poweronly considers his own attitudes towards the action p,and then expand the analysis to cases where otherattitudes are taken into account. By a series of ex-amples, we will exhibit typical uses of differentmodal expressions.

We will start by studying the two actor case, andfirst assume that the speaker is in power. The one inpower never has to consider the attitudes of thesubordinate. There are then two options: (1) sheexerts her power non verbally by using the whip, or(2) she adopts the imperative mood and commandsthat p be done.19 We will symbolise the secondsituation as follows:

1 > 2+ Gr p!

Do p!

The main relation (1 > 2) indicates the speakers great-er power. The three first columns represent thespeakers attitude to p, the speakers expectationabout the hearers attitude and the speakers

19Since the first situation is non-linguistic, we will ignoreit in this text.

expectation about the hearers expectation about thespeakers attitude, respectively. In this case, thesecond and third columns are irrelevant.

The first line of linguistic output is in Swedish, thesecond represents a translation of the Swedish outputrather than a complete English output of thesituation in question. Very often it is the case that thetwo concide, but the goal has been to complete theanalysis of Swedish modals.

If the one in power does consider the attitudes of thesubordinate, the most general case is ?, whichindicates a relevant but unknown attitude.

1 > 2+ ? Vill du p?

Do you want p?

Since it is assumed that the power relations areknown to the actors, a question of this kind will, byconversational implicature, have the force of acommand.

The next case is when the one in power expects thatthe subordinate has a negative attitude towards p.

1 > 2+ Du skall p!

You must p!

In this case, the interpretation is that 1, who has thepower, expecting that 2 is negative to p, orders 2 toperform p , and by the modal verb skall mustindicates the expectation of 2s reluctance.

The happy case when the one in power expects that thesubordinate has a positive attitude towards p willnormally not lead to any linguistic output, becauseshe will then just expect that 2 performs p:1 > 2+ +

The cases where 1 has a negative attitude to p can beanalysed in an analogous fashion.

Next, let us take a look at the corresponding versionswith reversed power relations. One case is when thesubordinate does not know the attitude of the one inpower. The power structure, however, forces him tofind out 2s attitude:

1 < 2+ ? Vill du p?

Do you want p?

Interestingly enough, this is the same phrase as in oneof the cases above. However, since the powerstructure is different, it does not have the sameconversational implicatures, but is now a genuinequestion. The difference between the two meanings is

-

9marked in the prosody: vill is more emphasized in thegenuine question than in the imperative meaning.

In the case when one expects that 2s attitude to p ispositive, the default is just to perform the action.In the case when 2s attitude to p is negative, as in thefollowing diagram, the default is to say nothing (andto refrain from doing p).1 < 2+

If the power structure is strictly respected, it isirrelevant (to the situation and the outcome of p ornot p ) no matter how much 1 wants p to beperformed. But 1 can always appeal and try to get 2to change attitude by informing 2.

+ ? Jag vill p.I want p.

The line reads: I want p, but I expect that you dont,but that is perhaps because you do not know that Iwant p.

Similar kinds of appeals can also be used in the earliersituation when 1 does not know 2s attitude:

1 < 2+ ? 020 Jag vill p.

I want p.+ ? ? Fr jag p?

May I p?

The subordinate has two ways to straighten thequestion marks, either to inform the one in power ofhis own attitude, as in the first example, where hefears that 1 is perhaps negative. The second way is toask about 1s attitude.

The reading for the tables containing three powers issomewhat different. Consider this case:

1 < 2, 1 < 3 + Jag mste p.

I must p.

As before, the first column represents 1s attitude,the second equally 1s expectation about 2s attitude,but the third column now represents 1s expectationabout a third and stronger power, that is notnegotiable. The example reads: I dont want and Iknow that you dont want, but there is anotherstronger power over me that I cant refuse.

Due to the objective character of the third person,as described above, negotiation between the third

200 is interpreted as either 0 or .

person and any of the participants present in thespeech act situation is not possible.

In the case where there is a discrepancy in attitudebetween 2 and 3, the attitude of the third power isalways the strongest, being unchallengeable. Theexample below reads: I dont want p, you claim thatI should p, but I may not p anyhow.21

1

-

10

speaker wants the hearer to pass the salt.22 Inliterature oriented studies, ways of expressingconversational implicatures standardly belong to therealm of style. In the present context, the choice ofstyle can be seen as the way in which the speakerchooses to express power relations.

Givn (1989:153) gives the following example of acontinuum between imperative and interrogative:

most prototypical imperativea. Pass the salt.b. Please pass the salt.c. Pass the salt, would you please?d. Would you please pass the salt?e. Could you please pass the salt?f. Can you pass the salt?g. Do you see the salt?h. Is there any salt around?i. Was there any salt there?most prototypical interrogative

(2) An appeal constitutes the subordinates means toset aside the power relation. A case like the follow-ing, where 1 is the subordinate should yield animmediate execution of p, as soon as 1 knows the willof the one in power.

1 < 2 +

But there is always the possibility of appeal:

1 < 2 + Fr jag slippa p?

May I be let off p?

(3) We have to differentiate between a negotiable (orat least potentially negotiable) power on the onehand, giving expressions like Jag fr inte sprngakassaskpet I may not blow the safe, signifying thatI am not allowed to blow the safe, and on the other, anabsolute power involved in Jag kan inte sprngakassaskpet, signifying that I cant do it, and there isnothing to do about it.

The role of the third power

Another consequence of the power structure is thatthe third person the non-person does not appear,except in declaratives. This means that there is afundamental difference in meaning between I want togo and He wants to go, in that the first directlyengages in elaborating the power relation in question,whereas the second is either a report of another powerrelation, or the speaker taking over the third persons

22We believe that the complex of politeness expressions isa game on establishing power relations involving delicateconversational implicatures.

role. (Cf. the acting/describing distinction mentionedin the introduction). The third person only appears inthe three part relations and in the epistemic uses (seebelow).

One major difference between our analysis and earlierattempts (notably Talmy) is the introduction of athird power, a third part in the power relation, whosemain feature is that it is not present in the very speechact situation, and therefore not immediately negoti-able. The importance of this distinction is clear if onerecognizes the separate subgroup of modal verbsappearing in three-part structures, notably mste andbr/borde (must and ought to).

Another feature that belongs to the realm of thethird power is the modal adverbs of uncertainty, likenog and kanske (maybe). They are used in the place ofquestions to mark a relevant but unknown attitude ofthe third power, like in the following:

1

-

11

One of our main theses is that the core meaning of themodal verbs is determined by a certain pattern ofexpectations. Such a pattern of expectations can occurin various power structures, but will be expressed bythe same modal verb.

We will next give an analysis of the core meanings ofthe Swedish modals.

Two actor modals

Vill25

The expressions containing vill want to typicallyoccur in the expectation pattern +?, i. e. when thespeaker wants p but is uncertain whether the hearerhas the same attitude. For example, if the speaker isthe subordinate, and the hearer the one in power (1 2), theone in power can, instead of directly exerting hispower, say Vill du p? Do you want p? when heexpects that the hearer does not know his attitude.The speaker will then, by conversational implicature,expect that the hearer understands the speakersattitude.

Vill is traditionally analyzed in terms of volition,where volition would roughly correspond to apositive attitude in our account. However, applied toa real world situation, volition will produce actionin the cases where nothing is in the way, and thelinguistic expression will only emerge when thehearer is in power and has a negative or unknownattitude.

1>2+ ? Vill du p?

Do you want p?Du vill vl p?You do want p, dont you?

In this example, the first case is unmarked and thesecond using the modal adverb vl marks the speakersinclination towards expecting +, i. e. the speaker isuncertain about 2s attitude, but weakly expects thatshe is negative.

Skall

The typical modal use of skall must occurs insituations where the speaker is in power, withexpectation patterns of the forms +?, +0, +, i. e.when the speaker wants p, he expects that the hearerdoes not want p, and he does not expect the hearer tohave a correct expectation about his (=the speakers)

25Although the Swedish modals have an infinitive, ex-amples will be represented by their verb stems.

attitude. In this situation, Du skall p! You shall p! isused to inform the hearer about the speakers attitude,and to remind him of the power relation.

Nowadays, skal l is mostly used temporally(paralleling the English temporal use of will, thatwas originally modal), where the conception of timeas a power may have mediated this shift.

Lt

The primary meaning of lt let is as an appeal, i.e. thesubordinate wants to suspend the power structurewith respect to p, like in the following example.

1 < 2+ Lt mig p!

Let me p!

If it is supposed that the power structure is non-negotiable, lt let is rather rarely used. It is usedmainly in the expression lt bli, marking the negativeimperative. The second case in the example belowmarks a concession. So the core meaning of lt isdetermined by the expectation pattern +, i.e. that 1 isnegative to p but believes 2 to be positive.

1 > 2 + Lt bli p!

Dont do p!Jag lter dig p.I let you p.

Three actor modals

Vill, skall and lt represent the two actor group ofmodals typically involving only two powers com-peting, while the rest of the verbs, kan, fr, mste, brare mainly used to show an interplay between threepowers, the two of the speech act, and another outside.

Kan/frIt seems that the etymological origin of kan can isknow.26 Since we view knowledge as a primarilysocial relation, this use of kan thus conforms to ourgeneral analysis. The other sense of kan, be able to, isderived from the social relation by depersonalizingthe situation, and can thus not be modelled by anexpectation pattern.

In the cases where kan is used positively, it does notnormally concern the action p directly, but rathersome means to accomplish p. For example, if the onein power orders the subordinate to get her somethingfor her hang-over, the subordinate may say The drugstore is closed, indicating that he does not know howto obey the order. The one in power can then indicate

26This sense of can is obsolete in modern English. Both canand know are derived from the same origin.

-

12

possibilities by saying for example You can go to thecity, where the pharmacy is open, or You can ask theneighbours, they may have something.

Connected with this is the fact that for the othermodal verbs, the attitude of the speaker towards theaction is determining the modal relation, while forcan this aspect is often irrelevant.

The pair kanfr in some cases parallel the pair canmay in English. According to our data, they aremostly used in the negative, like in the next example,where kan represents an unmarked case, and where frbears the mark of subordinance in another powerrelation being relevant to the current p27.

1

-

13

extension of the power relations. Apart from thepower relations between the speech act participants,the power of the evidence is accep ted as anautonomous third part.

For example, by uttering John must be home now,since the lights are on, the speaker indicates that theevidence forces him to conclude that John is athome.32

Modality in two worlds

One way of viewing the transition from the deonticto the epistemic use is as a metaphorical shift fromthe real world, to an epistemic world inhabited bypropositions. This is the approach of Sweetser (andTalmy after her). Sweetser (1990) analyses what shecalls diachronic metaphorical changes in somesemantic fields of English. She writes (p. 645):

Any sentence can be viewed under two aspects:as a description of a real-world situation orevent, and as a self-contained part of our beliefsystem (e.g. a conclusion or a premise). Asdescriptions, sentences describe real-worldevents and the causal forces leading up to thoseevents; as conclusions, they are themselvesunderstood as being the result of the epistemicforces which cause the train of reasoningleading to a conclusion. Modality is a specifi-cation of the force-dynamic environment of asentence in either of these two worlds.

There are two main disadvantages of viewing theepistemic uses of modals as metaphorical extensionsof the deontic uses. Firstly, in the analysis ofSweetser, there is no distinction drawn between theconstative and manipulative speech acts. We want tostress this distinction, which comes out naturallywhen we place the focus on the precedence of theconceptual structure over the linguistic expressionsproduced. Secondly, there is no such thing as twoworlds there is only the social world with itsdifferent attitudes and expectations.

Strengthening of

conversational implicatures

Another analysis of epistemic modals is provided byTraugott (1989), who has set up three hypothesesabout paths of semantic change (p. 3435).

Tendency I: Meanings based in the externaldescribed situation > meanings based in theinternal (evaluative/perceptual/cognitive) de-scribed situation.33

32The conclusion itself is thus an epistemic action.33> = diachronically preceed(s).

Tendency II: Meanings based in the external orinternal described situation > meanings basedin the textual and metalinguistic situation.

Tendency III: Meanings tend to becomeincreasingly based in the speakers subjectivebelief state/attitude toward the proposition.

Traugott views the shift as a gradual pragmaticconventionalization, more than as a sudden shift fromone world to another. The starting point forlinguistic change according to her view seems to bethe description of (temporally and spatially) presentevents. As a consequence, she sees the semantic changeas the conventionalizing of conversationalimplicatures (1989:50):

The process that best accounts for theconventionalizing of implicatures in thedevelopment of epistemics is the process ofpragmatic strengthening [] If one says Youmust go meaning You are allowed to go (theOld English sense of *motan), one can befollowing (or be inferred to be following) themaxim say no more than you must, i.e. theprinciple of relevance []. In other words,from permission one can implicate expecta-tion.34

Traugotts tendencies are of a very abstract nature,and it is difficult to relate them to cognitivemechanisms. Our model reduces the diachronic shiftto a gradual detachment of the evidence as anindependent power. The fact that the epistemic uses ofmodals are not present at early stages of linguisticdevelopment indicates that it is not obvious that alinguistic community must accept evidence as anentity that can be ascribed power.35

The role of conversational implicatures is to use themtogether with the utterance to draw conclusionsabout the attitudes and expectations of the speaker. Inother words it is not only the utterance but also theevidence concerning the conversational context andthe background knowledge of the hearer that deter-

34A similar phenomenon is mentioned by Traugott in thedevelopment of the polysemy of since , (p. 34, someemphasis added):

a polysemy arose in M[iddle] E[nglish] when whatwas formerly only an inference had to be construedas the actual meaning of the form, as in Since I amleaving home, my mother is mad at me. At that stagesince had become polysemous: in one of itsmeanings it was temporal and could have an invitedinference of causality ; in the other, it was causal.

35It seems that in certain illiterate societies, evidencecannot be treated as an abstract object, but must always betied to personal experience. (Cf. Luria 1976 and Grdenfors1994) The development of a written language provides amedium in which evidence can be given an existence that isindependent of the language users.

-

14

mines the force of the utterance. It is a small stepfrom this perspective on the context to view theevidence itself as a power. However small, this stepis crucial in the transition from the deontic to theepistemic uses of modal expressions.

The question is whether the shift from viewing theevidence as part of the context to viewing it as anindependent power can be seen as a metaphorical shift,as Sweetser and Talmy want it. In our opinion, theshift in meaning is rather determined by a pragmaticstrengthening of the role of evidence. This processinvolves no dramatic shift of domains like what istypically the case for metaphors.

However, there is no direct conflict between a meta-phorical analysis and one in terms of the power ofevidence and conversational implicatures. Traugott(1989:51) writes:

To think of the rise of epistemic meanings as acase of pragmatic strengthening is not to denythe force of metaphor (nor, indeed, does anexplanation based on metaphor deny the forceof pragmatic strengthening), because metaphoralso increases informativeness and involvescertain types of inferences []. The maindifference is the perspective: the metaphoricprocess of mapping from one semantic domainonto another is used in the speakers attemptto increase the information content of anabstract notion; the process of coding pragma-tic implicatures is used in the speakers at-tempt to regulate communication with others.In other words, metaphoric process largelyconcerns representation of cognitive catego-ries. Pragmatic strengthening and relevance[] largely concern strategic negotiation ofspeakerhearer interaction and, in that connec-tion, articulation of speaker attitude.

The power of evidence

Evidence cannot be a speaker or a hearer, so its role istypically that of the third person. In contrast tohuman agents, evidence, whether common or personal,has no attitudes in itself. The only thing that varies isthe strength or weight of the evidence, i.e., the amountof information that speaks in favour of a certainconclusion. The weight of evidence is what deter-mines its power.

Another difference between the deontic and epistemicuses of modals is that the objects of deontic modalverbs are actions, while the epistemic modal verbsconcern states of affairs. For, example in the epi-stemic use of He must have blown the safe, thespeaker reports that the evidence that is available toher forces her to the conclusion that the world is suchthat he has blown the safe.

In the deontic use, where the objects are actions, theutterances containing modals are speech acts. Incontrast, in the epistemic use, where the objects arestates of affairs, the function of the utterance is toreport. Thereby, it does not (directly) deal with thepower relations between the speaker and the hearerand the resulting demands.36 Being a report, anexpression containing an epistemic modal is primari-ly about the third person (or the non-person), whiledeontic modals used in speech acts typically concernthe first or second person, as we argued above.

Some prosodic phenomena

An interesting phenomenon is the deaccentuation ofthe epistemic modals. This seems to occur both inEnglish and Swedish. Thus, the must in He must be athome tends to be more strongly accentuated in thedeontic sense than in the epistemic.

A general principle is that the accentuated constitu-ents of a sentence signal what is subject to challenge the prosodic focus corresponds to the focus of thediscussion. The deontic senses deal with themanipulation of present states of affairs, while theepistemic uses report facts that are not subject tochallenge (Givn 1989). Hence, the scope of theepistemic modals is the complete sentence, and theepistemic interpretation of He must have blown thesafe is thus There is strong epistemic evidence forconcluding that he has blown the safe.

Although nobody seems to have studied this prosodicphenomenon for modals, it is in accordance with theprinciples in Anward & Linell (1976). They claimthat the more a linguistic constituent is lexicalized,i.e. treated as one lexical unit, the fewer accents ittends to have.37 For example, the edible hot dog hasonly one accent, while the pet version on a warm dayhas two.

In an analysis in terms of a mapping between twoworlds, like the one proposed by Talmy and Sweetser,there is no support for such prosodic phenomena. Asargued above, the linguistic accentuation correlateswith the degree of challengeability. So if thepragmatic strengthening advocated for by Traugottinvolves a gradual lowering of this challengeability,then the phenomenon observed here will supportTraugotts version, rather than the metaphoric viewof Talmy and Sweetser.

36Of course, a pure observational report can also, byconversational implicature, have strong deontic effects. Forexample, the report I noticed that you took the ten poundnote from the blind beggars hat can, in the right context,have devastating penal consequences.37This does not, of course, affect the emphatic stress thatcan be put on almost any constitutent in a phrase, like in HeMUST be home now, I DO see the lights on.

-

15

Graded epistemic modality

There is a rather clear epistemic gradation in theSwedish modals, ranging from possibility to nec-essity:

Han kan vara hemma nu. He can be home now.Han br vara hemma nu. He may be home now.Han skulle vara hemmanu.

He should be home now.

Han lr vara hemma nu. He is said to be homenow.

Han skall vara hemmanu.

He will be home now.

Han borde vara hemmanu.

He ought to be homenow.

Han torde vara hemmanu.

I dare say he is homenow.

Han mste vara hemmanu.

He must be home now.

Some of the modals notably skall, skulle and lrhave a clear evidential meaning component. Lt and f,have no typical epistemic uses, as far as we have noted.

CONCLUSIONS

We have proposed to view the core meanings of themodal verbs as determined by the power structure ofthe speech act situation where they are used. We havefound that the different participants expectationsabout each others attitudes combined with the socialpower structure largely determine the use, andthereby the semantics, of modals.

We have studied the Swedish modals, and to someextent compared them to their English counterparts.Our general semantic approach should, however, beapplicable to all languages with modal verbs.

Even though our work has been inspired by Talmy andTraugott, our analysis in terms of power andexpectations shows a way to extend and refine theirviews and brings out the underlying cognitiveprinciples that are required for a unified treatment. Inparticular, the social function of discourse is betteraccounted for by focusing on attitudes andexpectations about attitudes than by starting fromphysical forces.

Furthermore, we dont accept Talmy and Sweetsersanalysis of the epistemic modals as a metaphoricalshift from the deontics. In contrast, we propose thatthe epistemic modals arise by viewing evidence as anindependent power. This is probably connected withthe dissemination of literacy, since the materialcharacter of the written word on paper has

presumably promoted the acceptance of evidence as apower in its own right.38

We believe that our semantic apparatus can be appliedto linguistic and cognitive phenomena other thanmodals. For example, we claim that in expressionslike a suspected escape car and an alleged thief, theadjectives show the same epistemic power structureas the modals do. Furthermore, in conditionals likeThere are cookies in the box, if you want some, the if-clause seems unnecessary since the cookies are thereeven if you dont want them. We believe that bytaking expectations into account, in particular polite-ness conditions, such examples can be handled usingour approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is difficult to divide the contributions of the twoauthors to this joint paper. However, in rough outlinethe basic semantic concepts and the linguistic analysishave been developed by Simon Winter. PeterGrdenfors has proposed the formalism. PeterGrdenfors research has been supported by theSwedish Council for Research in the Humanities andSocial Sciences. Simon Winter gratefully acknow-ledges the support from Lundbergska IDO-fonden.We also want to thank Linus Brostrm, Lena Ekbergand Thomas Jokerst, and in particular Peter Harder,for constructive comments.

BIBLIOGRAPHYAndersson, T., 1994, Conceptual Polemics Dialectic

Studies of Concept Formation , Ph.D. thesis, LundUniversity Cognitive Studies, 27.

Anward, J. & Linell, P., 1976, Om lexikaliserade fraser isvenskan, In Nusvenska studier, 5556, Uppsala, 77119.

Austin, J. L., 1962, How to Do Things with Words , OxfordU. P., London.

Benveniste, ., 1946, Structure des relations de personnedans le verbe, Bulletin de la Socit de Linguistique ,XLIII, fasc. 1:126. Reprinted in Benveniste, 1966, 225236.

Benveniste, ., 1956, La nature des pronoms. In For RomanJakobson, Mouton & Co, Den Haag. Reprinted inBenveniste, 1966, 251257.

Benveniste, ., 1966, Problmes de Linguistique Gnrale,vol 1, Gallimard, Paris.

Grdenfors, P., 1988, Knowledge in Flux , The MIT Press,Cambridge, MA.

Grdenfors, P., 1994, The role of expectations in reasoning,in Knowledge Representation and Reasoning UnderUncertainty , M. Masuch and L. Polos (eds.), Springer -Verlag, Berlin, 1-16

Givn, T., 1989, Mind, Code and Context Essays inPragmatics, Lawrence Erlbaum Ass., Hillsdale, NJ.

38We owe this point to Peter Harder.

-

16

Grice, H. P., 1975, Logic and Conversation. In Cole &Morgan (eds), Syntax and Semantics, Vol 3: SpeechActs, Academic Press, New York, 4158.

Lakoff, G., 1986, Women, Fire and Dangerous Things What Categories Reveal about the Mind, TheUniversity of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Langacker, R., 1987, Foundations of Cognitive Grammar,Vol 1 , Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Luria, A. R., 1976, Cognitive Development Its Culturaland Social Foundations, Harvard U. P., Cambridge, MA.(Translation by Martin Lopez-Morillas and LynnSolotaroff of Ob istoricheskom razvitii poznava-telnykh protsessov , Nauka, Moscow, 1974.)

Lyons, J., 1982, Deixis and subjectivity. In Robert J. Jarvellaand Wolfgang Klein, eds, Loquor, Ergo Sum? Speech,Place, and Action: Studies in Deixis and RelatedTopics, John Wiley, New York, 10124.

Minsky, M., 1975, A Framework for RepresentingKnowledge, in P. H. Winston (red), The Psychology ofComputer Vision, 211277, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Palmer, F. R., 1979, Modality and the English Modals ,Longman, London.

Palmer, F. R., 1986, Mood and Modality, Cambridge U. P.,Cambridge.

Prn, I., 1970, The Logic of Power , Blackwells, Oxford.Rumelhart, D. E., J. L. McClelland, 1986, Parallel distri -

buted processing: explorations in the microstructure ofcognition, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Sadock, J., 1970, Whimperatives, in J Sadock & A Vanek(eds), Studies presented to Robert B. Lees by hisstudents , Linguistic Research, Inc, Edmonton, IL, 223238.

Searle, J. R., 1979, Expression and Meaning: Studies in theTheory of Speech Acts , Cambridge U. P., Cambridge.

Schank, R., R. P. Abelson, 1977, Scripts, plans, goals, andunderstanding, Lawrence Erlbaum, Ass., Hillsdale, NJ.

Sweetser, E. E., 1982, A Proposal for Uniting Deontic andEpistemic Modals. In Proceedings of the Eighth AnnualMeeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society , Universityof California, Berkely.

Sweetser, E. E., 1984, Semantic Structure and SemanticChange A Cognitive Linguistic Study of Modlity,Perception, Speech Acts, and Logical Relations , Doc-toral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Sweetser, E. E., 1990, From Etymology to Pragmatics Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of SemanticStructure, Cambridge U P, Cambridge.

Talmy, L., 1981, Force Dynamics , Paper presented atconference on Language and Mental Imagery, Universityof California, Berkeley.

Talmy, L., 1988, Force dynamics in language and cognition,Cognitive Science 2, 49100.

Tomlin, R., 1995, Mapping Conceptual Representationsinto Linguistic Representations: The Role of Attentionin Grammar , Dept. of Linguistics, Institute forCognitive and Decision Sciences, Univ. of Oregon, ms.

Traugott, E. C., 1989, On the Rise of Epistemic Meanings inEnglish: An Example of Subjectification in SemanticChange, Language 65 :1, 3155.

Winter, S., 1986, Srdragsanalys dess mjligheter ochomjligheter , Unpublished paper, Institutionen frnordiska sprk, Universitetet i Lund.

Winter, S., 1994, Frvntningar och kognitions forskning,Lund University Cognitive Studies, 33.

von Wright, G. H., 1963, Norm and Action , Routledge &Kegan Paul, London.