Slums create value in more ways than one: A case study of ... · PDF fileSlums create value in...

Transcript of Slums create value in more ways than one: A case study of ... · PDF fileSlums create value in...

Slums create value in more ways than one: A case study of Dharavi

1. Introduction

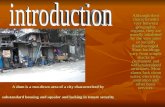

Slums represent two particularly distinctive features, high population density and a strong sense of community. In this paper I propose that from these characteristics a certain kind of value emerges that is not monetary in nature but which results in upward social mobility. I will be examining two theories that argue for these alternative forms of value, Social Capital theory and Motility theory. I will then illustrate and confirm the validity of these theories, using the case of a particular slum, Dharavi, in Mumbai. These theories and their application to a slum area such as Dharavi are important because slums usually have an undeservedly bad reputation, which is partly responsible for government-led slum rehabilitation schemes.

I chose the topic of my paper because I am interested in alternatives to existing or received thought towards social organization. Schools of Architecture and Urban Planning, like those in other disciplines are dominated by Western theory that is but one view of the world. However persistent dominance that can be traced back to colonialism and now associated with globalization asphyxiates alternative models, which may offer viable and sustainable solutions. Slums, when removed from their negative frame, can be described as organic, homegrown and in-formation environments1 offering an industrious yet sustainable lifestyle, rooted in community. It is the uncovering of this model and the value that it holds that fascinates me and that I would ultimately like to share with Western academia.

2. Background / Context

Dharavi is known as Asia’s largest slum, a phrase that has now become somewhat of a cliché. It started as a fishing village and then gradually grew as migrants who came after the 1950s and could not be employed by the mill industry settled it. Consequently, migrants took up work in other industrial sectors such as manufacturing and chemical. Many of these industries are very small-scale, producing embroidered garments, export-quality leather goods, and pottery and plastic in tiny manufacturing units spread across the slum. They sell in domestic as well as international markets. As a result Dharavi is a thriving economic center with an annual turnover of business estimated to be more than $650m (£350m) a year. (BBC). Along with expansion, Dharavi has also seen diversification in terms of ethnicity and religion.

3. Intuitive Hypotheses

I started out with the following intuitive hypothesis that I wanted to explore and validate through my case study of Dharavi: Collective social organization, which is integral to life in slum areas such as Dharavi, allows people to cooperate amongst and have an in-built support system based on

1 www.urbz.net

trust rather than monetary exchange. This can in turn “improve their lot” in ways that would not be possible if they were working individually, resulting in ‘collective upward mobility’.

4. Method

While case studies are most often used to devise theories, they can also be used to validate or illustrate theories and this is what I will be doing here. I chose to do my fieldwork not extensively but intensively. Therefore I will be focusing on case studies in a specific slum, Dharavi, in Mumbai. Ultimately my case for fieldwork in Dharavi rests not so much on its being ‘representative’ as on being sufficiently interesting and accessible for intensive case study.

Primary data: I initially planned to combine participant interviews with my own observations. However, for several reasons, namely the lack of time and the start of the monsoons that disrupted people’s routines, my ability to interview as extensively (in terms of number of people and range of topics discussed) was quite limited. I was only able to visit with the help of a local interpreter, Shyam, who is a Dharavi resident and who made navigating the area much easier, twice of the three times I visited. In these instances I recorded my conversations with Shyam as he translated my questions and people’s answers. While working with Shyam was certainly an asset, it was still difficult to communicate through an interpreter and I felt that elements of my questions were lost in translation. On a visit to Dharavi without Shyam, I initially felt quite uncomfortable interacting with people, particularly being so clearly foreign. Getting used to the intensity of the space, to the smell and other idiosyncratic features, was challenging. But as I grew accustomed to the environment, I developed certain techniques. Generally I found that on my own, approaching women felt much more natural and comfortable. I usually start with a “Namaste-ji”, or a smile and they often reciprocate. By the end I was going up to all sorts of women taking part in various types of activities, and asking them in my limited Hindi what they were engaging in, and establishing some sort of a connection through positive and friendly body language and facial expression. I also found that children were very easy to interact with as they speak more English and they are so excited to see strangers. Usually all they want to know is “what is your good name” and past that exchange they are pretty happy. Often they would want to high five or shake hands. Girls would often just shyly stare and then smile. Adults were not looking for anything from us, when they heard the uproar that their children were making they would come out and just ask us if we were well, or needed anything. This happened three times. I found it difficult to actually follow my questionnaire because I didn’t want to interrupt people from their work, or invade what were often people’s private homes. Secondary data: I have also supplemented my primary data with secondary data:

A) Interviews of slum-dwellers in Jari Bari slum, Mumbai from a film titled “Jari Bari: Of cloth and other stories” by Surabhi Sharma. Although this is from a

different slum than Dharavi, it is still in Mumbai and furthermore I can identify the parts that are relevant to Dharavi because of the level of familiarity I have gained with Dharavi through my observations on multiple visits. I will hereafter refer to this as ‘the documentary’.

B) Interviews of slum-dwellers in Dharavi conducted by the BBC.2

5. Theory

Having thus collected my data I was then better able to find appropriate literature to help me analyze and make sense of my data. I found social capital theory to be particularly relevant, and then I also realized that a significant factor, although not the only factor for Dharavi’s high levels of social capital was its spatiality. I therefore also looked at motility theory. Both social capital and motility theories provide accounts for potential social mobility. Social capital: “Social capital is the expected collective or economic benefits derived from cooperation between individuals and groups”.3 Social contract theory argues that features of collective life such as trust, norms, and networks “can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions”4 therefore resulting in upward social mobility. I have found the distinction between “bonding’ and ‘bridging’ social capital particularly relevant to making sense of my data. Bonding social capital refers to the “strong ties connecting family members, neighbors, and close friends sharing similar demographic characteristics” or “homogenous ethnic communities” and arguably facilitates ‘getting by’, working as an informal safety net.5 On the other hand bridging social capital refers to weaker ties or “horizontal connections”6 to people with ‘broadly comparable economic status and political power” but with different demographic, ethnic and geographical backgrounds.7 The way in which bridging social capital “encompasses people across diverse social cleavages” is arguably important for ‘getting ahead’.8 Motility: Motility is the link between spatial and social mobility. It is the “capacity of entities (e.g. goods, information, persons) to be mobile in social and geographic space”. Kauffman defines spatial mobility as “geographic displacement” and social mobility as “the transformation in the distribution of resources or social position of individuals, families, or groups within a social structure or network”.

2 BBC interviews 3 Das, Social Capital 4 D. Bhattacharya, N. G. Jayal, B. N. Mohapatra, S. Pai, Interrogating capital: The

Indian experience, Sage: London, UK (2004) 5 Das, Social Capital, p. 30 6 World Bank social capital 7 Das, Social Capital, p.30. 8 Social Capital in Europe

From the 4 types of spatial mobility outlined:1. Residential mobility (including residential cycles) 2. Migration (international and inter-regional) 3. Travel (tourism and business travel) 4. Day-to-day displacement (daily journeys such as commuting and running errands), the fourth, day-to-day displacement is the most relevant to Dharavi. 9 Urbanologists Rahul Srivastava and Matias Echanove developed an idea called the “Tool-house” concept, which offers a pragmatic means of building from motility theory. The “tool-house” is “a place where the actions of living and working are not neatly divided, where every single nook and corner becomes an extension of the trade of its inhabitants.”10

6. Working hypothesis

I then modified my hypothesis in light of these theories: Slum areas arguably offer both of these alternative forms of capital, social and motility, to financial capital. Their high population density and diversity, and close spatial proximity arguably lead to a great sense of community which should result in high levels of social capital and motility.

7. Data

I have organized my data into various practices that I observed while walking around Dharavi which I first describe and then analyze with regards to framework I have used to develop my hypothesis above. Fish market - Description

I visited the large covered fish market, the first in Dharavi twice. The space is disproportionately large in relation to the much smaller structures where most people actually live, but this is because this fish market and the Koli community, who first opened it, were Dharavi’s first settlers. On both visits, I am caught off guard by the pungent smell of fish. This distinctive odor, as well as the special way that Koli women wear their saris both work to differentiate the Koli community from other communities in Dharavi. Indeed, there is a specific name given to this community and in fact other Koli communities across Bombay, this is Koliwada, literally meaning “the habitat of the Kolis”11. My second time at the fish market it is devoid of any activity except for the scurrying of some very large rats. We meet a thin middle aged with a broom and learn that he lives right next to the market with his wife and daughter and is in charge of cleaning the market. We are then able to have a ten-minute conversation thanks to our translator/guide. First, I learn that the market is empty today is because the monsoons prevented the men from going fishing. In any case, it was relatively late in the afternoon so even if there had been a catch, most would have been sold by now. Next, the market cleaner explained that

9 Motility: Mobility as capital, p.749 10 www.urbz.net

fishing is very much a family business: the men go fishing, and the women sell the catch. A mother will pass this role down to her daughter, who will sell until she gets married, when it then becomes the role of the daughter-in-law. I ask how many women would sell here at one time and he explains that each of the many small wooden crates that almost cover the whole space is a different person’s stand. My rough count of these suggests that there are approximately 60 women. The crates are very close together, and I wonder how people choose from whom to buy fish. Analysis

Reviewing my data on the fishing industry, which is mainly from my own observations and interview, in the light of my chosen theories, I come to the following conclusions: The Koli are very much an example of ‘bonding social capital’ as evidenced by their geographic location, in a clearly defined neighborhood, with distinctive cultural customs (such as the sari style), their traditional trade and even arguably, the smell. In their work they are also organized in a way that emphasizes the strength of their community: the trade is passed down through the family, and spatially, women sit all together in the same market space. According to Social capital theory it would therefore seem that this developing of strong ties, and interdependence that exists in this sort of environment is critical to the functioning of this community. But arguably it does not allow for this community to experience social mobility. Bonding does nothing for social fluidity. Related to this, it is interesting that this is one of the few industries that takes place in Dharavi that requires products from outside Dharavi, in this case fish. I wonder to what extent the fact that Koli men need to go out and fish everyday, in comparison to most industries which have all the required materials located on site in Dharavi, actually has a negative impact on the community in terms of social mobility. There is however evidence that the fishing industry is witnessing some diversification due to Dharavi’s expansion, which means that the original fish market couldn’t meet all the demand. We did see some men selling fish on the side of a road. Then there is the very fact that people would come from all over Dharavi to buy fish as 10 years ago it was the only fish market. But before then women would walk around with baskets on their heads. This suggests going into different neighborhoods and communities, possibly leading to “bridging social capital”, more likely to result in upward social mobility.

Pottery-making – Description

I saw all the different stages of the pottery-making process on my first visit to Dharavi. First there was the pit of mud collected from various empty lots all around. I initially thought it was a compost heap, as it was hidden surreptitiously behind a small room. Then a couple minutes away there is an area with pottery wheels and then a covered wooden shelf structure where the pots can dry before they are put into the kiln for baking. After having seen all these different steps, like a workshop broken into the different steps of the manufacturing process, with each step taking place a couple feet away from each other in different parts of the same neighborhood.

Finally Shyam walked into one of the rooms that looked onto the small court area where there was the stand of drying pots. Inside was the potter, who welcomed us into his home. Downstairs in a small room there was a large wooden shelf that stretched all the way up to the low concrete ceiling, filled with earthen pots of various different sizes. This man lived upstairs with his wife, who was sitting on the wrought iron steps leading upstairs to their room when we walked in. Shyam afterwards explained to me that pottery is also a family business. Analysis

Again, most of my data on pottery comes from my own interviews and observations. In terms of spatial mobility of people and the necessary components required in the pottery-making, this is all within Dharavi and reduced to a distance overall amounting to less than one kilometer as all the different steps of the manufacturing process are in close proximity to each other. Sewing/dyeing cloth – Description

My third time in Dharavi I looked into a small open door to what seemed to be just any other dwelling, but I saw a group of about ten men sitting in front of sewing machines with piles of shirts and trousers. I was able to ask one of them who seemed to speak on behalf of the group several questions with Shyam’s help. I learnt that this clearly tight-knit group of young men, were not actually related to each other but that “they feel like they are family”, and that they work shifts of 8 to 9 hours a day. Later during that same visit, I saw similar groups of young men, though in rooms organized in different ways. Some were crouching next to large basins of dye and others hanging large sheets of cloth over wires that ran across the room. Subcontracted workers are subcontracted by external exporters to whom cloth and the measurements are given, they then pack the shirts and send the finished product to the docks for shipping to Singapore.12 Analysis

The documentary and Shyam also confirmed that people hear about employment in these different workshops through word of mouth, this is an example of how Dharavi’s strong community replaces traditional infrastructure to allow for spatial mobility of information in a way that might positively affect social mobility. Word of mouth can travel across neighborhoods and ethnicities therefore works as bridging social capital. While subcontracted workers may not benefit from the on-site availability of a market for their work, because they are targeting a market that is elsewhere (for example Singapore), they are benefiting from bridging social capital, gaining access to broader types of people and potentially further opportunities which might result in upward social mobility. Community keeps people here even if they lost the job that initially brought them.

12 Documentary

Day-to-day tasks/ chores - Description

Walking around Dharavi at any time of day, I saw many people, especially women, engaging in public or communal spaces in activities that I would normally expect to be done in private. In almost every alleyway I saw groups of women sitting on the ground outside one of their houses, engaging socially with each other. They are sometimes preparing food (soaking beans and the like, or rolling chapatti), or wringing laundry, or sewing, and always chatting amongst themselves. On a main road we walked past a particularly foul-smelling area, and later realized that it was a large block of communal toilets. I have also seen men, women and children carrying water in large pots, usually on their heads or shoulders. This fact is also addressed in the BBC interviews, as one woman says: “I don't have a direct water supply in my house - none of the houses in my area have a tap with running”.13 Interviewing Surabhi Sharma, the maker of the documentary after the screening, she explained to me that in a slum space, everything spills into everything else, everything is collective, and nothing is private. The community’s access to basic infrastructure such as water and electricity and basically to citizenship is only on a collective rather than an individual basis.

8. Discussion

I will now go back to the hypothesis and develop it, drawing on some of my data using the three-part framework, (Access, Competences, Appropriation) from motility theory, I am in fact seeking to make sense of the data in light of my hypothesis.

A) Access – “the range of possible mobilities according to place, time, and other

contextual restraints”14 Access is equalized for much of Dharavi. Spatially, Dharavi is quite uniform, though there will obviously be some areas that are closer to transportation links than others, transportation links are on the whole easily accessible from all of Dharavi. While there may be some fluidity between these in terms of employment, there remain defined neighborhoods in Dharavi as was evidenced by the Dalit area on the hill in Jari Bari as depicted by the documentary, which might cause some inequality. Access to infrastructure is on a communal basis. Commercial areas are spread quite evenly throughout. Access to information is high but this is less because of technology than close proximity and strong community connections. Strong access to information is then further enhanced by technology, especially mobile phones. Both my own interviews and the documentary suggested the main way that people found jobs was through word of mouth, and particularly through kinship or friendship connections. Access to raw materials is plentiful throughout Dharavi although there is a particular area where more industrialized recycling takes place. Many of the raw materials used in Dharavi’s small manufacturing industries are recycled from waste. Therefore transit time and cost is reduced, however, there may

13 BBC 14 Motility as Capital, p. 746

be the cost of processing materials in order for them to be recycled. A significant portion of what is produced may then be exported. However, what is sold in Dharavi goes is sold almost completely to residents. Therefore Dharavi is a particularly cheap place not only in terms of housing costs but also other living costs. One woman said: “It's the main reason why I don't want to leave Dharavi, because if I go outside everything will be so expensive that there is no way I would be able to afford anything.” (BBC)

B) Competences – “skills and abilities that may directly or indirectly relate to

access and appropriation”15 Different skills are an area that could result in different experiences in Dharavi and different chances for social mobility. While in general it could be said that amongst people of a certain caste, competences are roughly the same (because initially castes had to do with occupation or trade) and that people in Dharavi are roughly of a similar caste. Dharavi seems to offer more occupational fluidity. There is fluidity in terms of people’s occupations but they are not really going up or down just changing within the same sector.

C) Appropriation – “how agents (individuals, groups, networks, or institutions) interpret and act upon perceived or real access and competence.” 16

Both on an individual and community basis, Dharavi residents are extremely resourceful with regards to their lifestyle, they extract all the value they can from the slum and add their own. The result is the happy and yet industrious atmosphere everywhere. Individually, some make use of the good transportation links by choosing to commute in and out of Dharavi daily. Women will sometimes work in factories/workshops or as domestic maids in homes outside of Dharavi. Men will also work in factories outside of Dharavi. In which case the fact that “It is centrally located in Mumbai and travelling from here to any place in the city is very easy” (BBC) is valuable. But the majority of Dharavi residents seem to clearly take advantage of the living and working in the same place as a means for improving their lives, as discussed in the Tool-house concept. They are also extremely industrious and good at finding means to makes money using their skills and their skills are of value to the their local community or they find markets further afield. People look to work at home if they can because won’t have to deal with oppressive conditions at work, in order to not have to commute and in order to be able to take care of their children. One woman said that she would have to wake up very early (before 5am) and that sometimes would have to work two shifts which meant kids were left alone which is why she quit. In almost every alleyway I saw groups of women sitting on the ground outside one of their houses engaging together. There were several instances where the women were more clearly involved in an activity that went beyond self-sustaining activities

15 Motility: Mobility as capital, p.746 16 ibid.

into commercial activities, for example making brooms out of dried bits of plant and what looked like recycled string. Data from the BBC interviews of several women also supports this information. One woman said, “I work for about three-and-a-half hours in a home nearby, where I clean and dust and wash vessels and clothes. I return home by about 1.30pm. Then I make flower bands to earn some extra money. I cook dinner and supervise my children's studies. “17 Another woman explains, “I used to do some tailoring work, but I developed a swelling in my right arm and had to leave. Now I stay at home and look after my family. I occasionally take on some embroidery work and earn a little extra money.”18 Even streets are not just a means of transportation but seen as an opportunity for commerce and socialization, which in a sense increases efficiency both in space and time, but also seems to positively affect people’s level of happiness. On a collective level there is a culture of community and togetherness that contributes the welfare of everyone. This culture is partly due to the space which forces people to interact collectively but also the fact that migrants who have settled in Dharavi often carry with them aspects of village life, such as the community-centricity of life. Walking around Dharavi with Shyam, I always notice how he will pat little boys’ heads and run into several friends as we are walking around. However, the most striking example of the strength of the sentiment of community in Dharavi was on my third visit to Dharavi. As it started pouring with rain, we walked past a room near the recycling area where there is a father and several of his children all sitting together. The oldest looking girl is wringing laundry crouched at the entrance of their room. It turns out that the father is a friend of Shyam’s and he gestures at us to come in as he sees us walk past. He and Shyam catch up for a bit and suddenly I see Shyam pat his shoulder gently with a sad expression on his face. He then turns to me and explains that this man’s father has just passed away. He also explains that it is traditional amongst people here to have everyone over to your house to eat when a member of your family dies, so we have been invited. In the documentary I noticed how doctors and patients were first name terms, and several different people commented on the sense of community in the interviews conducted by the BBC: “Everyone sits, eats and sleeps together” and “I like it here because people are friendly and look out for me. If my husband is working late and does the night shift I don't feel scared because I think this is the safest place for us.”19

9. Conclusion

The original article on motility (Kaufmann et al., 2004) focuses on the importance of modern transportation networks (such as the TGV or Easyjet) in allowing people to cover large distances in much less time, producing new ways to work and live, and therefore positively impacting social mobility. The paper connects two very important ideas in the social sciences in a very interesting way: the relationship between spatial and social mobility. The basic framework developed by the authors

17 BBC 18 BBC 19 BBC

defines spatial mobility (of people, goods, and information) in relation to social mobility in terms of their access to, competences with and appropriation of this form of capital (motility). I have proposed that the framework can be productively applied to an environment that works very differently from high-speed Europe. When applied to my data, this theory shows that slums certainly offer value, but in a very different way. By the very nature of a slum’s spatial constraint and the culture that develops there, it too gives rise to new combinations of work and habitation. It seems that a sort of micro-city forms which not only permits but also encourages its residents to live and work in very close proximity. This results in “time-space compression” (for people, goods and information) not by increasing the speed but rather reducing the distance travelled. It is this compression, however it may come about, that Kaufmann and his colleagues link with “social fluidity”20. As stated early in this paper, slums create economic value for their inhabitants. In addition to this economic value, I am suggesting that another form of value is created in the slums. Indeed, there is significant research showing the correlation of high social capital with decrease of poverty.21 But really slums such as Dharavi offer something beyond this, which is a collective-organized, community-based society within a modern capitalist economy. This model has largely never been seen. With the appropriate government support (providing the lacking pieces of missing infrastructure such as sewage systems), a slum such as Dharavi could be a very attractive alternative to the increasingly troubled Western urban model, especially for a non-Western context.

20 Motility: Mobility as Capital, p. 746 21 Das, Social Capital and Poverty

10. Bibliography:

• Urban Planet: Life in a Slum, interviews conducted by the BBC, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/world/06/dharavi_slum/html/dharavi_slum_intro.stm

• S. Kumar, A. Heath, O. Heath, “Determinants of Social Mobility in Europe”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 37, No. 29 (Jul. 20-26 2002), pp. 2983-2987

• V. Kaufmann, M. M. Bergman, D. Joye, “Motility: Mobility as Capital”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 28.4 (December 2004), pp. 745-56

• R. J. Das, “Social capital and poverty of the wage-labour class: problems with the social capital theory”, Transactions of the Institute

of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 29, No. 1 (March 2004), pp. 27-45

• “What is social capital?” The World Bank, http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTSOCIALDEVELOPMENT/EXTTSOCIALCAPITAL/0,,contentMDK:20185164~menuPK:418217~pagePK:148956~piPK:216618~theSitePK:401015,00.html

• W. Van Oorschot, W. Arts, J. Gelissen, “Social Capital in Europe: Measurement and Social and Regional Distribution of a Multifaceted Phenomenon”, Acta Sociologica, Vol. 49, No. 2, Social Capital, (Jun 2006)

• R. Srivastava, M. Echanove, “Tool-house: Living and Working in Mumbai”, http://www.domusweb.it/en/video2/tool-house-living-and-working-in-mumbai-/

• R. Srivastava, M. Echanove, “Koliwada (Dharavi)”, http://www.urbantyphoon.com/koliwada.htm

• “Historiography and Case Studies”, Ch. 10, Case Studies and Theory

11. Appendix

a. Survey:

I am on the lookout for instances of collective behavior: Work: most likely to be men (but maybe chose a man and a woman)

- What is your job? Describe your job? - Is this work that consists of several parts? – Detail the process - Self-employed/employed? - Where does it take place? - Who works with you? How many people do you work with? - What would you not be able to work without? Everyday tasks: most likely to be women

Describe your daily routine Leisure : choose both a man and a woman

Describe what you do for fun Where does it take place How much time do you spend with family and friends

b. Photographs (on the next page)

Figure 1 The fish market, Koliwada, Dharavi

Figure 2 Earthen pots drying before baking in the kiln

Figure 3 Earthen pots after baking in the kiln

Figure 4 Collecting metal tins for recycling

Figure 5 Organizing wood parts for recycling

Figure 6 Diversification of fish selling - they're not women and they're not in Koliwada!

Figure 7 Walking down the steps over the railroad into Dharavi from Sion station