Site assessment audit of St Kilda Road/Kings Way … · John Gregson 340002 Healthy Communities 14...

Transcript of Site assessment audit of St Kilda Road/Kings Way … · John Gregson 340002 Healthy Communities 14...

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 1 of 11 Assignment 2

Site assessment audit of St Kilda Road/Kings Way precinct focussing on urban infrastructure

and its importance to neighbourhood walkability.

Introduction

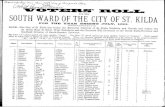

A site assessment audit of the area between St Kilda Road and Kings Way north of Dorcas Street in

Southbank (refer Figure 1 below) was completed utilising the ‘Healthy Urban Environments’ audit

released by the Heart Foundation (2009). The area is located just over 1 km from central Melbourne,

with significant office and arts precincts adjacent.

Figure 1: Study Area

The contrast between St Kilda Road and Kings Way, both major thoroughfares, was of interest,

particularly their observed effect on pedestrian behaviour. After analysis of a variety of pedestrian

conditions within the study area, it is demonstrated that careful small-scale replication of attractive

features can positively impact on community well-being by increasing the human-scale of streets.

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 2 of 11 Assignment 2

Particular assessment focus was placed on urban infrastructure and whether it supports and

encourages walking. The Department of Human Services states that “a strong link exists between the

built environment, health and wellbeing” (2001, p.17). A focus on walking was taken for a number of

reasons.

Firstly, the location of the study area is such that significant employment opportunities exist within 3

kms, a short walking distance for residents. EDAW (2009, p.4) states that Southbank has only

recently become a residential suburb and its residential population is characterised by young

professionals aged 20-34. Similarly, the area caters to large numbers of office workers, many of

whom walk from Flinders Station, the major arrival point of the suburban train network.

Secondly, walking provides essential physical exercise and facilitates unplanned social contact,

contributing to happiness. In high-income societies such as Melbourne, four diseases represent 80%

of the total disease burden; cardio-vascular disease, diabetes, chronic lung diseases, and some forms

of cancer. Lack of physical exercise is one of three key risk factors (Whitzman 2007, p.146).

Montgomery (date unknown, p.1) adds that Paris is reclaiming streets for pedestrians, with the belief

that cities can become engines of happiness.

Finally, Morabito (2001, p.13) highlights that transport, particularly provision of ‘walkable’

environments, is the number one priority of low-income earners to removing perceived physical and

locational barriers and improving their daily lives. Although Southbank is characterised by young

urban professionals, attempts to increase the population of common mobility disadvantaged groups

such as children and the elderly, must consider pedestrian infrastructure closely.

Study Area Analysis

Four main sites were chosen for close analysis, which all provide prescient insight into the

weaknesses and strengths of this focus area:

1. Triangle Park – Intersection of Dodds/Miles Street.

2. Kings Way – Intersection with Sturt Street.

3. [Wells Street/Dorcas Street/Anthony Lane – removed due to space restrictions].

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 3 of 11 Assignment 2

4. St Kilda Road – Between Coventry Street and Anzac Avenue.

5. ‘Tan’ Track – Adjacent St Kilda Road.

1: Triangle Park

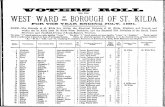

This ‘micro’ park is nestled between a fork in Miles Street and its intersection with Dodds Street. It

appears targeted towards those who live and work in the immediate vicinity, with connectivity only

directly provided by Dodds Street, a low traffic street, reflected by observed low-usage (two people at

lunch hour). However it contains well designed tables and bench seats, along with maintained

landscaped gardens and accessible footpath access.

Figure 2: Triangle Park

The park environment is attractive and quite interesting, with the curious feeling that it is ‘hidden’ due

to low-lying vegetation at its edge. Fortunately, the road environment on Miles Street is low-speed

due to its curvature, which ensures disruption and feelings of unease from passing traffic is kept to a

minimum. This is important as a study into ‘delightful places’ highlighted that 80% of respondents

associated relaxation with delightful places (O’Brien 2006, p.5). Interestingly, more than 60% of

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 4 of 11 Assignment 2

delightful places identified were in urban environments, with peaceful, beautiful and visibly green

areas most popular.

Good passive surveillance is provided by residential apartments adjacent (refer Figure 2), however

one criticism of this block is that the ground floor is dedicated to a private car park (refer Figure 3).

On other adjacent sides, passive surveillance is less effective with a dedicated office building, and

residential apartments with restricted views.

Figure 3: Triangle Park

2: Kings Way

Kings Way presents an overwhelmingly car-dominated thoroughfare with eight lanes of automobile

traffic, two separated tram lanes along the median and two footpaths hard up against either side of

the road, with no buffer between pedestrians and traffic except a standard kerb. The road alignment

either side of the Sturt Street intersection is straight and flat, encouraging higher speeds than the 60

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 5 of 11 Assignment 2

km/hr limit, and is patently unwelcoming and intimidating for pedestrians, creating a chasm between

neighbourhoods located on either side.

There is a large capture of residents from the study area who rely on the Sturt Street crossing of

Kings Way in order to access the Markets, café’s and shops of South Melbourne located a short

distance away (refer Figure 1: Study Area ).

Figure 4: Kings Way/Sturt Street Intersection

Figure 4 highlights the skewed alignment on approach from Coventry Street, requiring pedestrians to

undertake a zig-zag crossing of the intersection, reinforcing the lack of connectivity either side of

Kings Way. Due to traffic light sequencing, two minute waits for pedestrian lights is common, with

feelings of isolation and exposure experienced while waiting on the traffic island. The intersection

alignment creates a dangerous crossing for pedestrians who naturally want to take the shortest route

(illustrated in Figure 5) while driver behaviour turning into Kings Way can be unpredictable with four

lanes to choose from.

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 6 of 11 Assignment 2

Figure 5: Kings Way/Sturt Street Intersection

4. St Kilda Road

St Kilda Road is a grandly proportioned boulevard catering for pedestrians, cyclists, public transport

and vehicular traffic. A feature is attractive greenery, with adjacent parks, monuments and heritage

buildings (Victoria Barracks). Four rows of trees and grass nature strips along the road reserve

ensure greenery features prominently despite adjoining land uses.

The six-eight lanes of vehicular traffic are divided up effectively by on-road bike lanes, parking, two

tram lines and nature strips. Along with the gentle curvature, the road environment is much calmer

than Kings Way, despite the same speed limit of 60 km/hr, with lower vehicular traffic volume

observed. Thus, crossing the road is relatively stress-free for able-bodied people, while pedestrian

lights, dropped kerbs and tactile paving is provided at trams stops.

Despite a lack of active street frontages, a combination of an attractive, interesting environment and

surrounding land-use contribute to a high-use of the shared path by pedestrians, which is pleasantly

separated from vehicular traffic by a row of mature trees, nature strip, parking lane and on-road bike

lane.

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 7 of 11 Assignment 2

5. ‘Tan’ Track

The ‘Tan’ (refer Figure 6) is a highly popular and well maintained sandy track that encircles the Royal

Botanical Gardens and described as iconic to Melbourne (Only Melbourne, 2009). It is wide (3-4m)

catering to a variety of users, including recreational/fitness users (walking, running, cycling) and more

leisurely users such as families accessing the adjacent gardens.

Figure 6: ‘Tan’ Track

Popularity of the ‘Tan’ is very high immediately before and after work in particular as office workers

and nearby residents alike socialise and exercise, often in groups. Many people were also observed

driving to the ‘Tan’ to exercise, suggesting it offers facilities and attraction lacking in other suburbs.

Indeed, attractive gardens, monuments, water fountains, distance markers, prominent seating, lighting

and maintenance of a smooth track are inviting to all.

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 8 of 11 Assignment 2

Yet, does this fully explain the overwhelming popularity of a simple sandy track like the ‘Tan’? Is it

also the pleasing aesthetics? The good location, with large numbers of office workers and an

increasing resident population nearby? These undoubtedly play a major role. However, is there

something else that attracts us, more on the human scale?

As stated by Montgomery when describing the Champs-Elysees in Paris, the main attraction is not the

shopping, it is “for people to see each other” (unknown date, p.5). Drawing on evolutionary

psychology that has shown humans fare better through co-operation, and juxtaposing this with

modern cities, it is stated that “encounters we have on foot or by bike tend to build trust. It’s in the

eye contact we make as we choreograph our movements” (Montgomery, p.3). This has the simple

effect of making us feel good, possibly due to release of the hormone oxytocin when we feel calm and

connected (O’Brien 2006, p.9).

Could a similar effect occur around the ‘Tan’? Could it be that the popularity of this sandy track

among recreational and leisure users alike is not as much due to the pleasant leafy surrounds, but

instead the chance to mix and interact, however passively, with other people – “the electric possibility

of a thousand simultaneous stolen glances”? (Montgomery p.5). From the authors past use of the

‘Tan’, this is a valid theory.

Perhaps there exists a critical mass of pedestrian numbers that, once reached, results in pedestrians

themselves becoming the feature attraction. Can this be planned and replicated elsewhere, in

particular, to space constrained areas?

Recommendations

Reaching this significant pedestrian mass would appear, on the positive evidence of the ‘Tan’ and St

Kilda Road, to require basic infrastructure such as space and proportion, well maintained and

accessible paths, attractive green landscaping, trees, seating and lighting. Adequate space is the

most vital component, as the others may be retrofitted if need be, and is the primary focus of

recommendations.

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 9 of 11 Assignment 2

1. Side roads in the study area such as Dodds and Wells Street are commonly low traffic, yet

disproportionately large. Traffic lanes should be narrowed to minimum requirements, while

investigation of a one-way street system could further reduce pavement width, both reducing

the speed environment. Re-forming this additional space presents the opportunity to create

attractive pedestrian walkways of similar proportions to the ‘Tan’.

2. On-road parking is prominent. EDAW (2009, p.39) raise the possibility of extending the ‘no

new car space’ for new residential development from the Capital City Zone outwards to

Southbank as a way of controlling vehicle numbers. Taking this approach further, a ‘Park(ing)

Day’ concept could be introduced (World Changing 2008), whereby some parking spaces are

sacrificed to create small-scale attractions (such as in Figure 7 below), which, exhibiting

peacefulness and beauty, could be classed ‘delightful places’. Opportunity exists to trial

creative approaches with nearby arts colleges and do not necessarily require use of parking

spaces.

Figure 7: Park(ing) Day (taken from http://www.worldchanging.com/local/seattle/archives/008707.html)

Finally, the major issue of connectivity from the study area across Kings Way to central South

Melbourne requires a high-level response from local and state Government authorities due to the

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 10 of 11 Assignment 2

importance of Kings Way to vehicular mobility. Options appear limited without a reduction of vehicular

traffic and freight on Kings Way, unless major road tunnelling works are considered, possibly creating

significant parkland space where the existing road lies.

Conclusion

It has been highlighted that people associate ‘delightful places’ with peaceful, beautiful and visibly

green spaces. When surrounded by people on foot (or by bike), we have the opportunity to interact

and build trust, which, based on evolutionary psychology, produces feelings of calm and

connectedness leading to release of the hormone oxytocin, improving our well-being.

The ‘Tan’, as an iconic pedestrian attraction, and St Kilda Road generally exhibit peacefulness,

beauty and greenery. Replicating these characteristics to space-constrained streets within the study

area generally requires additional space, with a width reduction of low-vehicle trafficked roads and

use of innovative small-scale treatments such as those captured during Park(ing) Day proposed.

John Gregson 340002 � Healthy Communities

14 September 2009 11 of 11 Assignment 2

References Department of Human Services, Victoria. 2001 (updated 2006). Municipal Public Health Planning Framework: Environments for Health, Local Government Planning for Health and Wellbeing (Melbourne: Government of Victoria). http://www.health.vic.gov.au/localgov/mphpfr/index.htm EDAW 2009. “Southbank Structure Plan”, Background Report. Heart Foundation 2009, Healthy Urban Environments: Site Assessment Audit. Accessed 4 September 2009. http://www.heartfoudation.org.au Montgomery, C. [date unknown], The Happy City, accessed 11 September 2009, http://www.walkandbikeforlife.org/Articles.html Morabito, D. 2001, Snapshots of Life: exploring the barriers faced by people experiencing disadvantage, (Melbourne: Victorian Council of Social Services). O’Brien, C. 2006, A footprint of delight: Exploring sustainable happiness, (National Centre for Bicycling and Walking), accessed 11 September 2009, http://www.walkandbikeforlife.org/Articles.html Only Melbourne 2009, The Tan Track, accessed 11 September 2009, http://www.onlymelbourne.com.au/melbourne_details.php?id=11442 Wade, S., Bowerman, N. 2009, Southbank Precinct Strategic Planning Study. Healthy Communities

Seminar, 7 September 2009. University of Melbourne. Whitzman, C. 2007, “Barriers to Planning Healthier Cities in Victoria”, International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability, 3(1). World Changing 2008, Park(ing) Day and the bigger picture of small spaces. Accessed 11 September 2009. http://www.worldchanging.com/local/seattle/archives/008707.html