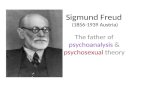

Sigmund Freud's 'Two Short Accounts of Psychoanalysis'

-

Upload

shiva-kumar-srinivasan -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

361 -

download

0

Transcript of Sigmund Freud's 'Two Short Accounts of Psychoanalysis'

1

BOOK REVIEW

Sigmund Freud (1991). Two Short Accounts of Psychoanalysis translated and edited by James Strachey (London: Penguin Books).

This volume from Penguin comprises two books on psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud: they include the ‘Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis,’ which he gave at Clark University, Worcester in 1909 and ‘The Question of Lay Analysis’ that he published in 1926 as an imaginary dialogue with an ‘impartial person’ to explain who should or should not analyse patients.

Both these books are an attempt to distil the very essence of psychoanalysis and make its precepts known to an audience of intelligent lay-people.

In order to do this, Freud minimizes his use of technical terms or tries to explain these terms in a language that is easily comprehensible to those who have not been trained as physicians.

The points that Freud raised are still relevant in contemporary debates about psychoanalysis and in working out the protocols of training for those who wish to practice analysis in psychoanalytic institutes and societies around the world.

Freud’s lectures at Clark were delivered in German, but written down and translated into English and many other languages around the world. The lectures were dedicated to Dr. Stanley Hall, the President of Clark University and a leading psychologist and educator in his own right. It was Dr. Hall who invited Freud and his associates to lecture at Clark University.

These were not the only public lectures that he gave. Freud’s expository works also include a famous series of lectures that he delivered at the

2

University of Vienna, but what makes these lectures different is that they constitute the very first set of lectures that he gave in the United States.

Freud was accompanied by his associates including Carl Jung and Sandor Ferenczi. Jung himself delivered two lectures at Clark University and Ferenczi played an important role in helping Freud to sketch these lectures before Freud faced his audience. Freud and his associates would refer to these lectures as equivalent to bringing the plague to the United States.

What they meant by the plague was the discourse of psychoanalysis because of its impact on not only the medical profession but on a number of other humanistic disciplines as well.

These lectures were published in the United States for the first time in a psychology journal in 1910, and Freud made an attempt to connect the findings of American psychologists like Sanford J. Bell from as early as 1902 in his lectures of 1909.

These lectures serve as an excellent point of entry for the layperson into the main precepts of psychoanalysis because Freud summarizes the bulk of his early doctrine in just a few lectures which can be read in a couple of sittings even by the uninitiated.

The first lecture was an attempt to delineate the origins of psychoanalysis in the medical practice of Dr. Josef Breuer at Vienna. Breuer had a patient named Bertha Pappenheim who is better known in the analytic literature as Anna O.

So Freud’s opening move in these lectures is to thank Josef Breuer (without whose support he could not have moved so decisively into psychology from the areas that he was working on like histopathology and neurology).

Freud points out the psychoanalysis was not invented but only elaborated by him from the embryonic form in which he found it in Breuer’s clinic.

3

The reason that Freud became better known as a psychoanalyst was because Breuer wanted to concentrate on his general practice given the resistance that was generated when the basic precepts of psychoanalysis were explained to the members of the medical society in Vienna.

Breuer also found that his marriage came under pressure because of the strong affects that his patient Anna experienced. The main difficulty in terms of clinical dynamics was that the phenomenology of the transference was not well-understood in the Anna O case.

Freud’s main contribution in the early years was to find out that the affective load which Breuer was forced to carry by patients like Anna was a regular feature of how patients repeat affective patterns from early childhood and was not necessarily an indication of whether Anna loved Breuer in her personal capacity as a young woman.

Freud’s attempt to clarify the difference between personal emotions and transferential emotions (which repeat affective patterns from how the patient related to his parents in his early years) was crucial in making it possible to practice psychoanalysis without being haunted by the fear that the patient would fall in love with the analyst.

Freud is keen to point out that it is not possible to analyse a patient without conjuring up these spirits from the past and the analyst should not flee the patient when transferential emotions become intense.

Knowing how to work-through transferential emotions without getting involved with the patient in a personal capacity is an important element in the training of analysts. These transferential dynamics were however unknown in Breuer’s early cases.

Freud was therefore anxious to ensure that those who aspired to be analysts would be able to recognize and work-through transferential affects in as hygienic a way as possible to ensure the integrity of the analytic relationship.

The first lecture also gave Freud a chance to explain the basic rudiments of his theory of the structure and phenomenology of hysteria. Freud also compares his model of hysteria with those of his precursors - Josef Breuer and Pierre Janet.

Freud’s main emphasis was on the idea of psychic conflict though he tried to incorporate the insights available from the theories of hysteria that were available when he was starting out. These include the theory of ‘hypnoid states’ (when a patient is especially vulnerable to hysterical

4

forms of repression) and the inability on the part of hysterics to synthesize mental content.

In the second lecture, Freud tries to explain the ‘resistance’ that patients put up to the possibility of being cured since the need to suffer is a constitutive feature of all the neuroses. Though this is an early formulation of psychic resistance, it was to play an important role in Freudian psychoanalysis.

Freud raises the problem of resistance in the question of lay analysis as well when the impartial person to whom he explains the analytic doctrine is taken aback when he is told that most patients do not want to be cured but are not necessarily conscious of their need to suffer either.

And, as Freud’s associate, Sandor Ferenczi, points out elsewhere, the problems of resistance and transference were the two main factors in clinical dynamics that is relevant not only in psychoanalysis but in just about any form of medical practice. That is why psychoanalysts emphasize that what is at stake in the practice of medicine is not the disease or the presenting symptoms, but the patient as a whole.

Another concept that is of relevance in these lectures is repression. Freud’s initial impression was that hynoid states were especially favourable to the repression of thoughts that were incompatible with the patient’s ego.

Later, Freud dropped the idea of hypnoid states and introduced a structural model of repression and the endless expenditure of psychic energy that is required to keep the primary repression in place through secondary forms of repression.

But all this was to come later in his papers of meta-psychology.

Here what is on offer is a more tentative model of repression that takes the form of a clinical observation and a theoretical intuition which Freud felt would be eventually subject to a more thorough verification.

In addition to these three concepts (i.e. transference, resistance, and repression), Freud also introduces the haunting formulation of the ‘return of the repressed.’

He illustrates this through a spatial metaphor. Suppose, Freud says, that his lectures are interrupted by a member of the audience, it may become necessary to ask him to leave the auditorium.

5

But it is quite possible that even after leaving the room, the expelled member may start knocking at the door and ask to be readmitted. In such a situation, argues Freud, it is analogous to the ‘return of the repressed.’

Repression, as he points out, does not destroy a thought that is incompatible with the ego; it merely moves it out of the conscious awareness of the subject.

It may subsequently become necessary to re-admit the member with a request that he should not make any further attempt to interrupt the lecture. If the member agrees, the repressed component has been re-admitted into the auditorium and worked-through to the satisfaction of all concerned.

The repressed thought and its derivatives will all have to be worked-through in their entirety if the analysis is to become successful and the patient declared cured. That is why analysis takes as long as it does.

In the third lecture, Freud explores the forms of psychic ‘distortion’ to which the repressed thought is subject to. All the formations of the unconscious like the dream work, the structure of jokes, errors in performance, and the patterns of free-association on the couch are subject to psychic distortions.

What this means is that interpretation in the analytic situation is necessarily a form of translation between psychic systems of which ‘consciousness’ is but a small portion and the bulk of the psyche comes under the category of the unconscious.

An important challenge for Freud – once he recognizes the ubiquity of the unconscious – (and differentiates between the structural and functional descriptions of the unconscious) is to relate it to his structural theory of the mind comprising the id, the ego, and the super-ego.

He does this in a later lecture, but what is at issue in this lecture is to make a case for free-association and dream interpretation as that which will provide a point of entry into the unconscious.

6

Freud was given to saying that those who aspired to be analysts should make it a habit to interpret their own dreams since the interpretation of dreams is the ‘royal road to the unconscious.’

In this context, Freud argues that his definition of dreams as a disguised fulfilment of wishes can be verified by examining the differences between the dreams of children and adults.

What Freud means by is this that the dreams of children are based on the residues of the day and are subject to less distortion than those of adults. That is children dream openly about what they want, but adults disguise what they want because the manifest dream must – like a filmmaker – take the censorship function into account.

That is why it is important to differentiate between the manifest dream and the latent content of the dream and the transformational grammar of the dream that constitutes how these levels relate to each other.

The latent content is what results when all the important elements of the manifest dream are subject to free association on the couch. It is that which the analyst and the patient dig out of the unconscious.

The subject of the third lecture then is distortion and how the formations of the unconscious are subject to distortion so that unlike the dreams of children the wish-fulfilment in the dreams of adults takes a disguised form; this will ensure that the censor in the psyche is not unduly alarmed and that the dream elements are worked through in analysis in small chunks through the process of free-association.

It is important to understand this clearly because once the analysis begins the patient will have dreams where it is not clear whether he is fulfilling his wishes or those of the analyst since the dream-work is subject to the vicissitudes of repression, resistance, and the transference.

The fourth lecture is an attempt to explain the sexual aetiology of the neuroses and how the psychoanalytic community came around to the importance of identifying the role that disturbances in the vita sexualis plays in the behaviour of the patient.

The best known instance of this is in the context of ‘psychic-impotence’ and on whether or not the patient has the ability to sublimate the object of his repressions.

An important argument in the Freudian doctrine on the importance of the sexual aetiology of the neuroses relates to the diphasic structure of

7

sexuality in human beings. Freud invokes the researches of Sanford J. Bell in this context since these were conducted in the United States.

So it is not the case that only his Viennese and European patients were subject to the explanatory scope of the sexual aetiology of the neuroses. Bell’s work on infantile sexuality actually preceded Freud’s Three Essays on Sexuality.

So the sexual theories of the Freudian doctrine that were subject to needless controversy are not merely those that are specific to European psychoanalysis but broached openly by American psychologists before Freud wrote about them in the context of his own patients.

That is why the work done by Bell, a leading psychologist in the United States, became a crucial precursor text for Freud in these lectures.

Freud also calls attention to his analysis of a phobia in a five year old boy named Little Hans to explain the relationship between infantile sexuality, the Oedipus complex, castration anxiety, and the typical phobias of childhood. Freud also relates his theories of sexuality to those of Kraft Ebbing and Havelock Ellis here and elsewhere.

The main difference between these theories is that the sexologists do not go beyond studying specific sexual disorders. The Freudian move was to connect the work of these sexologists with a theory of the subject comprising meta-psychological concepts like repression, resistance, symptom, transference, and the unconscious.

So what Freud did in psychoanalysis was to argue that a theory of the subject is necessarily mediated by a theory of sexuality. There is not much value addition for him in treating these theories separately.

The work of the psychologists and sexologists then converged in Freud’s theory of the subject and was applied in the analysis of the neurotics who constituted his case studies on hysteria, obsessional neurosis, phobia, and the psychoses.

Another important move that Freud made was to ask what the libidinal economy of development might be and delineate what forms of repression and fixation were most likely to affect its linear unfolding. Freud therefore concludes that psychoanalysis is ‘a prolongation of education for the purpose of overcoming the residues of childhood.’

The fifth lecture is an attempt to work out the conditions of possibility for falling ill. Why do neurotics fall ill in addressing life-situations which everybody else is able to manage? How do creative artists sublimate their

8

symptoms through works of art? Why do neurotics lose contact with reality? And how can psychoanalysis help them to rectify the situation?

In the attempt to answer these questions, Freud points out that the neurotic’s approach to reality is affected by the fact that his psyche is subject to incessant conflict between the forces of repression and libidinal thoughts that are incompatible with the high standards of the ego and super-ego.

Neurotics avoid reality not so much because they dislike reality but because any encounter with reality triggers off conflicts in their psyche which, in turn, leads to the generation of painful symptoms. These symptoms are like ‘compromise formations’ between the forces at war in the psyche.

It is therefore important not to conflate the patient’s symptoms with the underlying neurosis. So, for instance, two different types of neuroses may throw up the same or similar symptoms.

Freud was fond of pointing out in his studies on hysteria that once a symptom is in place the neurosis will use and re-use the same symptom to express a range of meanings.

That is why it is not enough to remove the symptoms; it is more important to understand why the patient’s affects are constantly displaced from one symptom to another and relate the symptom to the structure of the neurosis.

What should analysis do when it identifies the libidinal thoughts that constitute the object of repression? Freud points out that these libidinal thoughts are easier for an adult to handle than for a child who has subjected them to repression.

What analysis can make possible is to substitute the harshness of the repression from childhood that produces an efflorescence of symptoms with something milder in the form of a ‘condemning judgement’ in adulthood.

This will make it possible for the neurotic subject to gain from a lifting of the repression and the endless expenditure of psychic energy needed to maintain the repressions already in place.

The energy that is freed up in this process of analysis can be deployed more productively by the subject in the pursuit of work or love. That is, the lifting of the repression and the sublimation of the instinctual forces at

9

work should lead to better relationships at work and in the patient’s personal life.

Sublimation is an important psychic mechanism for Freud; it is not only a precondition for mental health but an absolute prerequisite for any kind of cultural achievement.

‘The Question of Lay Analysis,’ is a dialogue from 1926 that attempts to explain the basic precepts of psychoanalysis to an ‘impartial person’ who is then asked to decide what the intellectual formation of the analyst should be like.

The need for the dialogue was related to the question of whether Theodor Reik, a colleague of Freud’s should be allowed to practice psychoanalysis in Vienna where, unlike Britain, only members of the medical profession could train or practice as psychoanalysts.

Freud intervened privately with the authorities with a set of arguments in support of Reik.

The arguments in favour of lay-analysis in this book are meant to give readers a feel for what sort of arguments Freud might have invoked in support of including those with a humanist background into the psychoanalytic movement.

This book also provides Freud an opportunity to argue that expanding the circle of analysts to include lay-analysis is more likely to ensure the success of the Freudian movement in different parts of the world.

As Freud grew older, he was increasingly concerned about the need to preserve the integrity of the analytic doctrine even as he wanted to see it applied in a number of innovative contexts and disciplines.

In order to make that possible he wanted to explain the basic precepts in a dialogic form to those who might be interested. Freud’s audience includes not only doctors and scientists, but also the intelligent layperson.

10

Another advantage in explaining psychoanalysis through expository works of which Freud did a great many in number is that it helps to increase the number of patients who might want to attempt an analysis.

So it is not enough for Freud to preach to the converted but to be constantly on the lookout for those who could be roped into the profession.

The main themes in this book include the following:

the structure of the analytic profession; the question who really qualifies to see patients; the relationship between psychoanalysis, psychiatry, and the medical profession; the forms of knowledge and training that is ideally required to make it as an analyst; the forms of subjectivity and sexuality that constitute the theories of psychoanalysis; the nature of analytic interventions and the range of neuroses that it is equipped to tackle; and the different theories of the mind in psychoanalysis (including the differences between the topographical and structural theories).

Many of these topics have already been covered in the five lectures. I do not want to repeat the arguments, but pick up only those that have not been previously discussed.

The main difference between these two books is that the five lectures directly explain what the precepts of analysis are and the arguments that can be proffered in their support. Here, however, what is at stake is the analytic profession itself.

There is a difference then between concentrating on the conceptual structure of psychoanalysis per se and the institutional structure of the analytic profession.

The structure of the profession becomes even more challenging to describe or delineate given that analysis is practiced in different parts of the world and each of these parts has its own needs and requirements and relationship with the medical profession.

While both these books are written with the lay reader in mind, the latter incorporates these arguments to appeal to the professional interests of lay analysts as well.

11

This volume, to conclude, should be mandatory reading in any introductory course on psychoanalysis. While there is a huge and ever growing literature on psychoanalysis, Freud’s exposition of his own work is the best way to get started.

SHIVA KUMAR SRINIVASAN