Shenpen sel - Tibetan Buddhism...SHENPEN ÖSEL 3 T he Chinese invasion of Tibet and the ensuing...

Transcript of Shenpen sel - Tibetan Buddhism...SHENPEN ÖSEL 3 T he Chinese invasion of Tibet and the ensuing...

Shenpen ÖselThe Clear Light of the Buddha’s Teachings Which Benefits All Beings

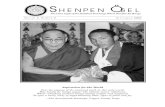

The Very Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

Volume 1, Number 2 October 1997

If there were a practical utility in following after agitating thoughts,if they actually made us function more effectively, that would be one thing. But,

in fact, the kleshas that we generate and the agitation they bring up areunnecessary and do not make us function more effectively at all. Therefore, they are,

from any point of view, unnecessary and inappropriate.

Phot

o by

Rys

zard

K. F

rack

iew

icz

2 SHENPEN ÖSEL

Volume 1 Number 2

Shenpen ÖselThe Clear Light of the Buddha�s Teachings Which Benefits All Beings

Editorial policyShenpen Ösel is a tri-annual publication of KagyuShenpen Ösel Chöling (KSOC), a center for the studyand practice of Tibetan vajrayana Buddhism located inSeattle, Washington. The magazine seeks to present theteachings of recognized and fully qualified lamas andteachers, with an emphasis on the Shangpa Kagyu andthe Karma Kagyu lineages. The contents are derived inlarge part from transcripts of teachings hosted by ourcenter. Shenpen Ösel is produced and mailed exclusivelythrough volunteer labor and does not make a profit.(Your subscription and support are greatly appreciated.)We publish with the aspiration to present the clear lightof the Buddha�s teachings. May it bring benefit and mayall be auspicious. May all beings be inspired and assistedin uncovering their own true nature.

StaffEditorLama Tashi Namgyal

Managing editorLinda Lewis

Copy editors,Transcribers,RecordersGlen Avantaggio, AlanCastle, Ryszard K.Frackiewicz, Yahm Paradox,Chris Payne, Rose Peeps,Mark Voss

Mailing crewMembers of theSeattle sangha

Contents (click on number)

3 Establishing a Place That Will Be of Immense Benefit to the World

7 Proper Motivation, Posture, and Mental Technique forthe Practice of MeditationBy Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

15 Transforming Samsaric Consciousness Into the Five WisdomsBy Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

24 Taking RefugeBy Kabje Kalu Rinpoche

34 A Note on the Use of Honorifics

35 On Tilopa�s Six Essential Points of MeditationBy Lama Tashi Namgyal

37 On the Virtues of Tranquility MeditationBy Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche

38 And How Does One Abandon Desire?By Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche

SHENPEN ÖSEL 3

The Chinese invasion of Tibet and the ensuing exodus in 1959 brought scores ofremarkable Tibetan lamas first to India and then to the West and other partsof the world. Among these was Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche. Among Kalu Rinpoche�s

many gifted disciples is Lama Norlha, whom Kalu Rinpoche established in 1976 asthe director and resident lama of his New York City dharma center, Kagyu DzamlingKunchap. He subsequently established him as the director of all of his dharma activ-ity on the East Coast.

In the ensuing years, at Kalu Rinpoche�s request, Lama Norlha established amonastery and three-year retreat center on the Hudson River in upstate New York, aswell as some ten to fifteen satellite dharma centers in the eastern United States. At

Establishing a Place That Will Beof Immense Benefit to the World

Aerial view of the Kala Rongo Monastery for Women

Lama Norlha

Phot

os c

ourt

esy

of K

agyu

Thu

bten

Chö

ling

4 SHENPEN ÖSEL

the same time he continued to engage in activity tohelp assure the survival and expansion of theTibetan Buddhist tradition in India.

Lama Norlha was born in the Nangchen regionof eastern Tibet, and at the age of five enteredKorche Monastery, where he later completed twothree-year retreats. Sometime between the originalChinese invasion of Tibet and the end of the Cul-tural Revolution in the late 1960s, Korche Monas-tery, which housed about 500 monks, was com-pletely destroyed, the monastic community dis-persed, and the monks all made to return to workand to secular life. The practice of Buddhism wasbanned at that time.

In the early 1980s the Chinese relaxed theirsuppression of Buddhism somewhat, and in 1982,Lama Norlha and his students began sendingmoney to Nangchen to rebuild Korche Monastery.In 1984, Lama Norlha was permitted by the Chi-nese government to visit his home country for thefirst time since 1959. By that time, Lama Norlhafound that the three-year retreat facility had beenrebuilt, a few houses had been rebuilt and recon-struction of the main shrine building had begun.

During this visit, Lama Norlha taught exten-sively in the three-year retreat, and gave novicenun�s ordination to 100 women. He was also able tobring Jamgon Tai Situ Rinpoche to Korche, whogave many teachings and empowerments, andofficially recognized two reincarnate lamas of greatimportance to Korche, who were subsequentlyenthroned. Shortly thereafter, Thrangu Rinpochewent to Korche and gave full ordination to 125monks and 150 nuns.

Since that time, Lama Norlha and his studentshave sent funds to continue the rebuilding andrefurbishing of Korche Monastery, to establish amonastic college for monks who have finishedthree-year retreat, and to establish an organizationcalled Lama Gyupa, through which Westerners cancontribute to the support of monks who havecompleted three-year retreat, allowing them tochant, study, meditate, care for the monastery, andserve the religious needs of the surroundingvillages.

Lama Norlha and his students have also agreedto send help to the colleges of three other nearby

monasteries, Depa Damkar, and Samge. They arealso assisting Chapa Gon Monastery and Convent,and hope soon to be able to assist Chobra andSherpa monasteries as well. Lama Norlha predictsthat, if these programs become strong and success-ful, they will not only bring benefit to the monas-teries in question but to the entire country of Tibetand to all the sponsors and sponsoring organiza-tions as well.

As these activities were developing at Korcheand the surrounding monasteries, and espe-

cially after the ordination of 150 nuns, the need forseparate but parallel facilities and opportunitiesfor the nuns became apparent. At that time LamaNorlha started looking to an isolated valley to thesouth of Korche Monastery.

This valley is the home of the Dzachu River,one of the headwaters of the Mekong River. Thevalley�s northern extreme, called Kala Rongo, is avery sacred place. Guru Rinpoche (GuruPadmasambhava) practiced there for many years,and the region is also home to such holy beings asthe five Tseringma sisters (goddesses who weredisciples of Milarepa), Karak Khyungmo Tsunma,and Genyen Shiwa Dorje. Chogyur Lingpa, the lastof the 108 great tertons prophesied by Guru Rin-poche, also retrieved the terma (treasure texts)known as Tukdrup Barchay Kunsel at Kala Rongo.

On three separate occasions�in 1976, 1979,and 1980�the Sixteenth Gyalwang Karmapa,Rangjung Rigpay Dorje, asked Lama Norlha toestablish a dharma center there, prophesying thatimmense benefit to the world would result. Therehad been no religious facility there for many hun-dreds of years.

In 1984, Lama Norlha traveled to Kala Rongowith a group of lamas to perform blessing ceremo-nies, during which time many auspicious signsoccurred. In 1990, he traveled there again withSangjay Tenzin Rinpoche and 300 monks andnuns. Together they did the practice discovered asterma there by Chogyur Lingpa, called TukdrupBarchay Kunsel, for eleven days and nights with-out interruption in order to consecrate land for amonastery for nuns.

The nuns then began construction of a six-mile

SHENPEN ÖSEL 5

shrine hall. With the nuns, he performed specialpractices of Green Tara, the Heart Sutra and theOffering of Four Hundred to avert obstacles. TashiDawa, one of Lama Norlha�s American dharmastudents, spent twenty-eight days in solitaryretreat at the Guru Rinpoche cave in the cliffs1,000 feet above Kala Rongo.

The nuns who have graduated from retreat livein their own small houses on the mountainsidenear their monastery, and assemble morning andevening to chant and practice in the main shrinehall. They also chant many special services at therequest of patrons in nearby villages, who attendthe services and make offerings to the nuns andthe monastery. For the first time, the nuns nowhave ample supplies of milk and butter, sinceLama Norlha arranged for 105 yak cows offered tohim during his stay at Korche Monastery to bebrought to Kala Rongo.

American dharma students have sponsored1,300,000 recitations of the Green Tara practice at$200 per 100,000 recitations, and have offered$2,500 toward 1,000 Nyungnes (the fasting prac-tice of 1,000-armed Chenrezig). These practiceshelp pacify difficulties and are often requested onbehalf of specific people; they also bring benefit tothe monastery�s region and to the benefactors who

road to the building site. Lama Norlha commis-sioned statues of Guru Rinpoche, the SixteenthGyalwang Karmapa, and Situ Rinpoche to beoffered to the monastery. Finally, in 1991, withfunds donated by members of Kagyu ThubtenChöling, the nuns built retreat facilities, a commu-nal kitchen, and outbuildings, and began construc-tion of the main shrine hall.

In 1992, Lama Norlha again returned to KalaRongo to inaugurate the first three-year retreat forfifty nuns. After the retreat began, he bought atruck for the monastery, and forty more nuns livingin shacks they had built on the hillside continuedconstruction of the main building, assisted byabout 250 nuns who resided in the surroundingvalleys and villages. Abo, a former administrator ofKorche Monastery, assumed directorship of thework in 1994, and now oversees the training ofnuns preparing for retreat as well as the day-to-day operations of the community. The first three-year retreat at Kala Rongo was completed in 1995,and fifty more nuns are now training in the secondretreat.

While visiting Kala Rongo in 1996, LamaNorlha gave empowerments from the Shangpa andKarma Kamtsang lineages to the nuns in retreatand also to the public in the now-completed main

Lunch break at Kala Rongo

6 SHENPEN ÖSEL

If you would like to make a donation toLama Norlha�s efforts at rebuilding the

monastic community in Tibet, please fill in thefollowing form and mail to:

Kagyu Thubten Chöling127 Sheafe RoadWappingers Falls, NY 12590

Name

Address

City/State/Zip

Day phone/Evening phone

Options for support:

¨ For one or more nuns at Kala RongoMonastery for Women for one year in theamount of $150 US per nun (the totalamount needed to provide one year�ssustenance for one nun in Tibet)

¨ For the ongoing construction and develop-ment of Kala Rongo Monastery for Womenin Nangchen, Tibet

¨ For the ongoing construction and develop-ment of Kala Rongo Monastery for Womenand for Korche Monastery (for men)

¨ For one or more monks at Korche Monas-tery for one year in the amount of $150 USper monk (the total amount needed toprovide one year�s sustenance for onemonk in Tibet)

Please make checks payable to Kagyu ThubtenChöling. All donations are tax-exempt.

sponsor them.Currently, the interior of the monastery�s shrine

hall is being painted and decorated. A protectorshrine is under construction on the top story, andon-site artists are making statues of the protectorsChakdrupa, Bernagchen, Palden Lhamo, and DorjeLekpa. Rooms are being prepared for Situ Rin-poche and the Gyalwang Karmapa.

Thankas of the lineage and the sixteen arhatsare displayed on the upper level of the shrine hall,and recently completed murals on the lower levelportray the Buddha, lamas, siddhas, yidams, andprotectors.

Next year Lama Norlha hopes to establish amonastic college for the nuns, comparable to theone at Korche Monastery. He would also like tobuild a retreat facility at Kala Rongo dedicated tothe practices of the Shangpa Kagyu lineage whichtransmit the profound teachings of the two femalemahasiddhas, Niguma and Sukkha Siddhi, tocomplement the already existing and operatingretreat center dedicated to the practice of theKarma Kagyu lineage, the lineage of Tilopa,Naropa, Marpa, Milarepa, Gampopa, and theKarmapas.

Lama Norlha has expressed great satisfactionwith the Kala Rongo Monastery, its excellentbuilding, which was finished in a remarkably shorttime, and the nuns� practice, diligence, accomplish-ment of learning, and joyful frame of mind. As thenumber of women who have completed the three-year retreat at Kala Rongo increases through theyears, there is no doubt that dharma practice willflourish there and that the prediction of the Six-teenth Gyalwang Karmapa will be fulfilled.

SHENPEN ÖSEL 7

By The V. V. Thrangu Rinpoche

In May of 1996, The Very Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche gave a series of teach-ings on the practice of meditation. The first teaching from that series ran in our lastissue. The following is the transcript of Rinpoche�s teachings the morning of May 25. Theteachings were orally translated by Lama Yeshe Gyamtso.

I would like to thank all of you for coming here out of your interest in dharma ingeneral and meditation and vajrayana dharma in particular. Pursuing thispractice of meditation and the study of vajrayana is extremely beneficial and

useful, because, in general, all of the goodness of the human life and all of the abilitywithin the context of the human life to actually benefit others and affect others in apositive way comes from a cultivation of dharma in general and in particular fromthe practice of meditation.

Next, in accordance with the custom of our tradition, the Karma Kagyu, I wouldlike to chant the lineage supplication. Now, the particular lineage supplication which

Proper Motivation, Posture,and Mental Technique for the

Practice of Meditation

The Very Venerable Thrangu Rinpoche

Phot

o by

Rys

zard

K. F

rack

iew

icz

8 SHENPEN ÖSEL

we use is used in all the Tibetan and overseaspractice centers of our tradition, and in fact, it�sused by individual practitioners as well. The reasonis that this particular liturgy was composed byPenkar Jampal Zangpo, who was a disciple of theSixth Gyalwa Karmapa, Tongwa Donden, and theroot guru of the Seventh Gyalwa Karmapa, ChötragGyamtso. Penkar Jampal Zangpo lived for eighteenyears on an island of which he was the only inhabit-ant. He lived in a cave on that island. And the islandis in the middle of a lake in the north of Tibet calledSky Lake or Namtso. And, for the eighteen years ofhis living there, he devoted himself entirely tomeditating upon mahamudra, ofwhich he generated a decisive real-ization. At the end of these eighteenyears of retreat, he composed thislineage supplication, and, therefore,we regard it as embodying theresult of all of his experience. Andwe consider it to have great bless-ing. So, now we�ll recite it. Please doso with a recollection of its signifi-cance and with confidence. (Chants.)

Whether we are practicing thedharma of the vajrayana or

listening to dharma or teaching it, weneed to possess a pure motivation fordoing so. Pure motivation here refers tobodhichitta. Now, we have all entered the gate ofthe genuine dharma, so therefore, in general, ofcourse, we don�t have a negative motivation, andwe�re very fortunate to have the motivation we dohave, to practice dharma. But, at the same time,because we are ordinary people, at times ourmotivation may become somewhat impure. It�snecessary, therefore, to turn inward, and toactually look at your motivation, and see what itreally is. If your motivation is a good and genuineone, then you should delight in that and cause itto expand. But if you find that your motivation isa negative one, is based on a fixation on a self andso on, then simply let go of it and generate a puremotivation. Now, when you consciously generate apure motivation, initially it may seem as thoughyou�re faking something, but in the long term you

are not really faking anything, because byintentionally cultivating, gradually it will becomereal and very much part of you. And here, by puremotivation, we mean the attitude that you are doingthe practice or study in order to benefit all beings.

Because we possess the beginningless habit offixation on the self, then it is natural for us, as far asour motivation goes, to desire our own happiness andour own benefit as our primary wish or goal. This isnot particularly a bad motivation; it�s just a small-minded or petty motivation. The small scope of this�the wish to benefit only yourself, which is characteris-tic, at best, of a lesser vehicle�is not wide enough,

not big enough, to serve as theproper motivation for thebodhisattva training of themahayana. Now, if you recognizethat this is your motivation, again,let go of the self-obsessive qualityof it, and generate the intentionthat what you�re doing be ofbenefit to all beings who fill space.

This motivation of wishing topractice and study in order tobenefit all beings without excep-tion is a type of bodhichitta orawakened mind. And this type ofbodhichitta is said to require twocharacteristics. The first is that it

be compassion directed at all beings, which is to saythat your intention be to benefit all beings who fillspace. The second characteristic is that it have intelli-gence or wisdom; and in this case, that means thatthe benefit you are attempting to accomplish for allbeings is not merely a temporary benefit but theirultimate liberation, their ultimate freedom. So pleaselisten to the teachings with the motivation of bodhi-chitta that possesses both this impartial compassionand this intelligence or wisdom.

Because this motivation of bodhichitta is soimportant for the practice of vajrayana, we possessa number of methods for increasing it and intensi-fying it. In general, these include, of course, medi-tations upon love and compassion, and in particularthe practice of taking and sending, or the taking ofsuffering and the sending of happiness. Taking andsending, or tonglen, is a practice in which you

. . . by puremotivation, wemean the attitudethat you aredoing thepractice or studyin order tobenefit all beings

SHENPEN ÖSEL 9

you will, through doing this practice, come to experi-ence the conditions of suffering through doing it,the conditions of suffering which afflict others.Because in the practice you�re cultivating a virtu-ous state of mind, a positive state of mind, whichcannot become a cause for suffering, such as expe-riencing the sufferings of others and so on. Never-theless, because that is what you are imagining,and because what you�re cultivating is the readi-ness to actually undertake the suffering of others,it�s natural that, when beginners start to practice,they experience some fear. Now, if you find thatthere is fear that inhibits your ability to do the

practice, then it�s appropriate toimagine in the center of your hearteither a white HRI syllable, alsovery, very luminous and brilliant,like the rays you breathe out, or, ifyou wish, simply a mass of brilliantlight. And when you breathe in allthe smoky, murky, grim stuff, thenyou think that, rather than its fillingyour entire body, it all dissolves intoand subsides into the HRI.

As well, there exists the uncom-mon vajrayana method of enhanc-

ing compassion, which is meditation upon thebodhisattva Avalokitesvara or Chenrezig. This is atechnique for removing the suffering of others andespecially for enhancing your own love and com-passion. Chenrezig is the embodiment of the com-passion of all buddhas and bodhisattvas, and, assuch, is regarded as a wisdom deity and not as anexternal deity. Therefore, we tend primarily torelate to Chenrezig as the embodiment of our ownfundamental nature. Because of this, while it is thecase that, in certain practices and at certain phasesof the practice, we visualize Chenrezig above ourheads�we externalize him�nevertheless, becausewe are fundamentally viewing him as the embodi-ment of the compassion of all buddhas and thewisdom of all buddhas, and because the wisdom ofall buddhas is our own essential nature, or buddhanature, and because we wish to reveal this natureby removing the secondary stains or obscurationswhich obscure it, and by revealing it to enhanceour own compassion and so on, therefore, the

imagine taking into yourself all of the suffering andcauses of suffering which afflict others, and imag-ine giving to all others all of the happiness andcauses of happiness which are within you.

Normally this practice is coordinated with thebreathing, which is to say that, as you breathe in, youthink that you breathe in all of the sufferings of allother beings, freeing them from these sufferings, andthat as you breathe out, you send out with yourbreath all of your own happiness and virtue and soon, and that other beings thereby receive these andenjoy these things. Now, the meditation is imaginingsomething, and yet it actually generates, over time,the intention in practitioners to beable to actually take on to them-selves the sufferings of others andactually benefit others and relievethe sufferings of others.

The practice of taking and send-ing, or tonglen, is coordinated withthe breathing, and so therefore it isone of a variety of meditation prac-tices which uses the breath. But, inaddition, it uses visualization, andspecifically the visualization of lightor rays of light. When you do thepractice, normally you consider that in front of youare all the countless sentient beings that exist. And,as you breathe out, you think that rays of brilliant,white, very, very luminous, brilliant light come out ofyou and strike and engulf all of those beings, causingall of the happiness and causes of happiness�virtue,and so on�that have up to now been within you, totransfer to those beings, causing them to actuallyexperience this happiness, to possess this happiness,as well as the cause of future happiness. And as youbreathe in, you think that you take from all of thesebeings all of their misery, all of their suffering, and allof their pain, as well as the causes of their pain, inthe form of murky, smoky, grim�call it light, but it�shard to call it light. It�s sort of smoky, grim light. And,that you inhale this, and that they are thereafter free ofall of this suffering and the causes of future suffering.

Now, according to the meditation, you areactually taking onto yourself or into yourself thesuffering and causes of suffering which would other-wise afflict others. But there is no actual danger that

It�s natural thatwhen beginnersstart to practice[tonglen] theyexperiencesome fear

10 SHENPEN ÖSEL

principal practice related to Chenrezig is to visual-ize ourselves as Chenrezig, to think of our body ashis body, our speech as his speech, and our mind ashis mind. And that is the basic format or basictechnique of the Chenrezig meditation practice.

Now, the actual form the deity takes can vary.There are forms with a thousand arms and a thou-sand eyes, and there is the four-armed form, and soon; and any of these forms will basically lead to thesame result. The fundamental characteristic whichthey all have in common is that Chenrezig embodiesthe tremendous peace of complete compassion.

The key point is that, when youimagine yourself to be Chenrezigor visualize yourself as Chenrezig,you are not merely thinking ofyour body as a different type ofbody. You are relating to the body,speech, and mind of the figure allat once. Now, in order specificallyto relate to the mind of Chenrezig,then you visualize, in the center ofyour body, at the level of the heart,a six-petalled lotus, and in thecenter of that lotus, you visualizethe compassion, the great compassion of allbuddhas, in the form of a brilliant white HRIsyllable. Now, surrounding that, you visualize thesix-syllable mantra OM MANI PEME HUNG. And,then, rays of light go out from the mantra andpurify the afflictions of beings.

Now, in general, Buddhists view the types ofexistences there are, the types of realms there are,as six different types of realms. These are held tobe caused by the preponderance of one or anotherof the six fundamental mental afflictions orkleshas, which produce, subsequently, those corre-sponding types of experience. So, in order to purifythese, then you correlate each of the syllables ofthe mantra with one of these kleshas and theirresults. So, for example, you think that from thesyllable OM, the first syllable of the mantra, raysof light shoot out and purify all of the arrogance ofall beings. Arrogance is the cause of rebirth as agod. Then, from the second syllable, MA, rays oflight shoot out and purify and remove all of thecompetitiveness or jealousy which afflicts any and

Our main concernas practitionersis the recognitionof the truenature of thingsor dharmata

all beings. And jealousy is the cause of rebirth as anasura, who are very powerful and quarrelsomebeings. Then, from the third syllable, NI, rays oflight shoot out, and these purify passion, which isthe root or the cause of rebirth as a human beingand the experience of the human sufferings of birth,aging, sickness, and death. From the fourth syl-lable, PE or PAD, rays of light shoot out and purifyall of the mental dullness of all beings, which is thecause of rebirth as an animal, which rebirth ischaracterized by suffering due to bewilderment.Then from the fifth syllable, ME, rays of light shoot

out and purify and remove all of thegreed which afflicts all beings.Greed is the cause of rebirth as apreta or hungry ghost, which experi-ence is marked by tremendoushunger and thirst. And, finally, thelast syllable, HUM, radiates lots oflight that purifies the affliction ofanger, which is the cause of rebirthin the hells and the experience ofintense heat and cold.

So, you�re visualizing that theserays of light are removing all of the

sufferings and causes of suffering that afflict allbeings, and that, as a result, all beings become bothhappy and free. So this is an effective method ofenhancing or developing your love and compassionfor all beings. But it also gradually reveals theinherent or innate great compassion which is withinyou and which is the essence of the wisdom of allbuddhas and allows this to reveal or express itself.It is, therefore, a very effective technique.

So, whether you are studying or listening to orpracticing dharma, you need this motivation of loveand compassion, and therefore we have specificpractices to enhance it and develop it: in general,meditations on love and compassion; in particular,the precise instructions of taking and sending, andespecially the extraordinary vajrayana techniquessuch as the Chenrezig meditation and so on.

Now, our main concern as practitioners is therecognition of the true nature of things or

dharmata. And in order to achieve this recognition,we need to let go of or relinquish those afflictions

SHENPEN ÖSEL 11

which obscure our capacity to recognize it. And weneed to enhance or expand, or allow to be revealed,the wisdom which can recognize it. Now, the pro-cess of removing what obscures this nature andthereby revealing what recognizes it, as well as thenature itself, has to begin with the accomplishmentof what is called tranquility or shinay. Now, in fact,shinay as a practice and as a result has two as-pects: it has the aspect of peace or tranquility,which means the pacification of the disturbance ofthought, and it has the aspect of stillness, which isthe capacity to rest the mind. And these are the twoqualities attained through shinayor tranquility practice.

Now, in order to accomplishthese, the actual technique, theactual practice, as well, has twoaspects. The first of these is thephysical technique or physicalposture, and the second is themental technique.

Of course, the main thing inmeditation is the mind and not thebody, because it is the mind thatactually performs the meditation.But at the same time, our mindsinhabit or rely upon our bodies, so,therefore, physical posture isextremely important.

Now, the physical posturewhich was practiced by all of thefounders and lineage holders ofthe Kagyu tradition is called the seven dharmas ofVairochana. Now, Vairochana is the name of, aparticular buddha and it also literally means �theilluminator.� Now, there are two reasons why thisposture is called that. One reason is the literalmeaning of Vairochana. The posture is called theseven dharmas of the illuminator, of illumination,because, if you take this posture, your mind�snatural clarity is enhanced or brought out, andtherefore the recognition of your mind�s nature isgreatly facilitated through the posture itself. Theother reason why this posture is called that is thatthe buddhas or victors of the five families, of whomVairochana is one, are correlated with the fiveaggregates�which is to say that our five aggre-

The physicalposture whichwas practicedby all of thefounders andlineage holdersof the Kagyutradition is calledthe sevendharmas ofVairochana

gates or skandhas are held in their true nature tobe these five buddhas. Now, Vairochana is the purenature or essence of the aggregate or skandha ofform. And, therefore, since it is through physicalposture that the experience of form as an aggregate istransformed into the experience of its pure nature asthe Buddha Vairochana, and, on the basis of that,that the other aggregates can be worked with andgradually transformed, then for that reason as wellthis posture is called the seven dharmas or sevenpoints, you could say, of Vairochana.

The first of the seven points which make up thisposture is the placement of the legs.The traditional explanation of this isthat the legs should be crossed inwhat is called vajra asana or vajraposture, which is where the legs arefully crossed with the feet placed onthe opposite thighs. Now, if you cancross your legs in this manner, this isthe best posture, but if you cannot, itdoes not mean that you cannot medi-tate. The specific quality of the fullycrossed or vajra posture is that it�sextremely stable. So the point of thisposture in general, and this first pointin particular, is that your sittingposture be as stable as possible. Now,the reason for this is that, if youmeditate standing up or walkingabout, which, of course, are acceptablepostures and actions in post-medita-

tion, your mind will be scattered. So, rather thanstanding or walking, we meditate sitting down. Youcould also meditate lying down, and specific practices,such as the dream and luminosity practices, can beconducted in that way. But lying down is not the bestposture for ordinary meditation because, just asstanding up or walking makes your mind scattered,lying down makes your mind torpid. Sitting is thehalfway point in between the two, so your mind isneither too dull nor too excited. If you can sit on theground on a cushion, with your legs crossed, that�sexcellent, but if you can�t, it�s also acceptable to sit ona chair.

The second point of posture is the placement ofthe hands. This is said to be the placement of the

12 SHENPEN ÖSEL

hands in the gesture of evenness or even place-ment. Now, quite often, this is taken to mean theactual mudra of even placement, which is found iniconographical paintings and statues, in which theleft hand is placed palm up in your lap and theright hand is placed palm up in or on the left hand,as in, for example, the position of the BuddhaAmitabha, and so on. And this is acceptable as ameditation posture. The meaning of the words�even placement,� however, has a wider connota-tion. It simply means that the hands should beplaced at the same level, should be placed evenly,as opposed to, for example, holding one hand aloftin space and placing the other onedown on the ground. So it�s alsoacceptable to place the hands palmsdown on the thighs behind theknees. Either one of these interpre-tations of this second point of pos-ture is fine.

The third point of posture is thatthe spine be straight, which meansthat you sit up straight. The reasonwhy it�s necessary to sit up straightwhen you�re meditating is that yourbody and your mind are very con-nected. Specifically, your mind rideson, or is founded in, the winds orenergies, which depend upon thechannels which are present withinyour body. So if your posture is bent or crooked, ifyou�re leaning to the left or to the right or you�releaning forward, then the channels will be bent aswell, and if the channels are bent, then the windswon�t flow smoothly and your mind will be in astate of agitation or unrest. If you sit up straightand your channels are straight, then the winds flowsmoothly and properly, and your mind will benaturally at rest.

The fourth point is that the upper arms bespread like the wings of a vulture. Now, whatactual form this takes depends upon which of thetwo positions of the hands you are using. If you areusing the position where the hands are placed palmup in the lap, then it means that, rather thanallowing your elbows to be stuck to your sides, youbring them outward somewhat, like spread wings.

If you�re using the posture where your hands arepalms down on the backs of the thighs just behindthe knees, then, instead of allowing your elbows tosink and be extremely bent, you straighten themsomewhat. In either case, the function of thisaspect of the posture is to make your entire posturesomewhat more erect, and the function of that is topromote the clarity within your mind. So, by doingthis to your upper arms and elbows, then yousomewhat prevent the occurrence of mental dull-ness in meditation.

The fifth point of posture is that the neck beslightly bent, which is to say that you�re not stick-

ing your chin out. The reason forthis is that by bending the neckslightly, bringing the chin in, thenyou naturally enhance your mind-fulness and alertness.

And the sixth aspect of postureis that the tongue touch the palate.And the reason for this is that thiswill cause less saliva to be presentin your mouth and cause you tohave to swallow saliva less often.Now, this sounds extremely unim-portant, but when you�re actuallypracticing meditation, if you con-stantly have to swallow saliva, it�svery distracting.

The seventh point of posture isthe gaze. Now, if your eyes are closed when youmeditate, this tends to make your mind dull. But,on the other hand, if your eyes are wide open andyou�re staring at what you see, then this will dis-tract you. So, the gaze for meditation here is to lookstraight, is that you look naturally straight for-ward. Now, when you�re practicing tranquility orshinay, you would tend to look straight forward asfar as left and right is concerned, but slightlydownward as far as up and down is concerned. Andwhen you�re practicing lhaktong, or insight, youwould still look straight forward as far as left andright is concerned, but slightly upward as far as upand down is concerned. In any case, you don�t directyour attention to what you see. You don�t try not tofocus the eyes, but you don�t send your mind afteryour vision. So, whether you see things or not,

If you sit upstraight and yourchannels arestraight, then thewinds flowsmoothly andproperly, and yourmind will benaturally at rest

SHENPEN ÖSEL 13

whether your eyes are focusing clearly or not, yousimply don�t follow it, you don�t run after it. And,instead, you look at your mind. In other words, youperform the meditation.

Well, those are the seven points of posture,which are called the seven dharmas of Vairochana.At the same time, when you implement this, yourbody needs to be comfortable, which is to say thatthe posture should be neither tense nor rigid, andshould not be uncomfortable. This means that ifany particular point of the posture is painful oruncomfortable for you�if it causes pain in yourarms or pain in your legs or pain in your spine orback�then you should not force yourself to takethis posture. There�s no rule that all seven points ofthis posture have to be present in order to medi-tate. The point of the posture is to allow yourchannels, and therefore your winds, to come com-fortably to rest through taking a certain physicalposture. But if taking this posture defeats its ownpurpose by generating too much tension and pain,then you should not force yourself to do it, and youshould not think that all points of this posture areabsolutely essential for the practice of meditation.

In Tibet, there arose eight principal traditionsof meditation practice. The initial progenitors ofthese eight traditions are called the eight chariotsof the practice lineages. Now, one ofthese eight traditions is calledseverance, or chöd, and the sourceof the teachings of chöd was aTibetan woman, [a mahasiddha]named Machig Labdrön, and she istherefore considered one of theseeight great teachers who foundedthe practice lineages. Now, in herteachings on meditation, she saidthat the physical posture is relax-ation of the four limbs. Now, whatthat means is that one of the mostessential points of physical postureis that you relax your muscles, yourjoints, and your sinews, that you not attempt tomaintain the physical posture with physical exer-tion or muscular exertion. Now, this means, whenyou�re practicing, if you discover tension, physicaltension, in a specific part of your body or part of

your posture, then you should consciously relaxthat part and let go of that tension. She furthersaid the mental posture or the mental technique isto destroy fixated perception. Now, here, �destroyfixated perception� means to neither follow norexpel thoughts, just simply let go of them as theyarise, neither to attempt to follow their content norto attempt to get rid of them or chase them out.And the posture of speech, or the technique ofspeech, is to sing melodiously of experience. Now,this means that the actual use of melody and so onin liturgy�for example, in supplications and soforth�can actually enhance meditation practiceand experience. In any case, the physical posture,as she said, needs to be one where your muscles arerelaxed.

So that is the physical posture.

Now, the mental technique that has beenpresented by most teachers of our tradition is

to follow the breath. And, indeed, this was taughtby the Buddha, who said, �When thoughts areintense, follow the breath.� And because it is atechnique of tranquility meditation or shinaypractice that is appropriate for anyone, it�s alwaysokay to use this technique. Sometimes, however, it�salso helpful to let your mind simply rest, without a

specific object to focus on other thanitself. So sometimes just let yourmind rest without following thebreath, provided you�re not dis-tracted. But what I�m going to talkabout now is not a specific techniqueyou use, but how you relate to themeditation of tranquility in general.

Normally, we have a lot ofthoughts running through ourminds, and many of these are basedon recollections of or thinking aboutthe past. Others are thoughts thatbeckon the future�speculationabout what may happen or what we

want to happen. Now, when a thought arises that isconcerned with the past, then simply let it go. Andwhen a thought arises that is speculation about thefuture, also, simply let it go.

Now, thoughts about the future can present

Thoughts aboutthe futurecan presentthemselves ashaving somespecial status,being veryimportant

14 SHENPEN ÖSEL

freedom, and so on. But, while those are your motiva-tions, in the context of the meditation, you do notentertain them. In other words, the thoughts, �Iwould like this to go well; I would like this medita-tion to work out; I�m afraid it might not; I�m afraidI�m thinking too much,� have no special status.These are thoughts just like any other thoughts. Sowhat you are cultivating here is simply allowing yourmind to rest naturally in present experience, and nothought that could possibly arise in that state is an

exception. And, therefore, any thoughtis just simply let go of naturally.

Now, initially, you can only do thisfor a very brief period of time. And thefaculty which you are applying at thatpoint�and it�s also a term for theexperience or stage of experience�iscalled �placement.� And placementhere is simply being able to rest yourmind for a very brief period of timewithout thinking about the past orthe future. Now, as you continue topractice, then these very, very briefperiods of placement will start tosomewhat lengthen�which is to say,the period of time during which youcan rest in present awareness withoutbecoming distracted by a thought,without losing awareness to athought, will lengthen. And whenthese periods get somewhat length-ened, then that stage and that facultyis called �continual placement.�Continual doesn�t mean unbroken orcontinuous; it just means slightlylonger. And then there is the furtherdevelopment of being able to return

from distraction, and this is called �returning place-ment,� or �returning to placement.� And this is beingable, through the use of mindfulness and alertness, torecognize that you�ve become distracted and to return tothis placement, this state of direct or simple awareness.

Well, these are the various points of the mentaltechnique. So, we could stop here for this morning,and conclude with the dedication. If you have anyquestions about any of this, there will be time to askthem this afternoon.

If you allow yourmind to simplyrest in directexperience of thepresent momentand are notdrawn by thecontents of thethoughts thatarise in yourmind, then yourmind will cometo abide in astate of naturalpeace, which isextremely helpful

themselves as having some special status, beingvery important. You may think, �I have to thinkabout this.� When that thought arises, then simplyremind yourself that there are twenty-four hours ina day, and, at this moment, you have designatedthis time as meditation time, not as thinking-about-the-future time. And you can simply say toyourself, �I will think about this later.�

Now, rather than thinking about the past orthinking about the future, what is recommended inmeditation is simply to maintain adirect awareness of your presentexperience, the present moment.And this means that, whilethoughts will continue to arise�and they may be extremely in-tense, they may have a strongemotional tinge or content tothem�simply don�t follow them,don�t get involved with the contentof thought. Now, this does notinhibit in any way the clarity ofyour mind. Not following a thoughtdoes not make you less aware. Itmakes you less conceptual. So, ifyou allow your mind to simply restin direct experience of the presentmoment and are not drawn by thecontents of the thoughts that arisein your mind, then your mind willcome to abide in a state of naturalpeace, which is extremely helpful.

Now, when you rest in aware-ness of the present moment and donot think about the past or thefuture, then for a short time notmuch thinking will happen; notmany thoughts will appear. And this resting in thepresent moment is not the same thing as trying toget rid of thoughts. It�s not like the thought, �Imust get rid of all my thoughts,� which is athought, or, �I must cultivate a state of non-conceptuality.� It�s not a recollection or reflectionupon your intention and motivation in meditation.It�s a state that is, in itself, free of thoughts of hopeand fear. Now, we are not free of hope and fear. Wehope to attain buddhahood. We hope to attain

SHENPEN ÖSEL 15

The technique of meditation that we looked at this morning was one in whichyou have no particular object on which you focus, but rather in which youallow your mind to come to rest naturally. Now, the ability to allow your

mind to remain at rest without a particular object on which you focus depends uponthe presence of the faculties of mindfulness and alertness. Essentially, mindfulnessis the actual recollection or memory of your intention, which is the recollection thatyou are attempting to remain without being distracted. By being distracted, wemean following thoughts, getting involved in the content of thoughts. And mindful-ness is therefore the faculty of recollecting that you are engaged in the act of medita-tion and are not going to follow your thoughts. Mindfulness is a samskara, a mentalformation, and as long as it is present in the act of meditation, as long as this mind-fulness is present, then your mind can remain at rest. And the mindfulness also willbring out the natural clarity or lucidity of your mind and will produce a state ofmental stability. As long as this mindfulness is present, then you will also possessalertness as well.

In order to practice meditation, you need to understand something about thecharacteristics and workings of your mind. This is studied throughout the Buddhisttradition and, in particular, in the vajrayana tradition. The first thing that needs tobe understood is that we can make a distinction between the mind and mental

The Very Venerable Thrangu Rinpoche

Phot

o by

Rys

zard

K. F

rack

iew

icz Rinpoche’s Seattle teachings on

the practice of meditation continuewith this transcript from theafternoon of May 25, 1996. LamaYeshe Gyamtso was the translator.

TransformingSamsaricConsciousnessInto theFive Wisdoms

By The V. V. Thrangu Rinpoche

16 SHENPEN ÖSEL

This mentalreplica is not adirect experience,but a vagueapproximation,which forms thebasis for thesubsequentconceptuality ofrecognizing it assuch and such, orgood and bad

sensation. So the fifth consciousness is called eitherthe body consciousness or the tactile consciousness.

The sixth consciousness is the mental conscious-ness, and it�s always enumerated by the learned asthe sixth because in the case of any of the first fiveconsciousnesses, it will ensue after them or followupon them. In general, the object of the sixthconsciousness is all things, anything that can bethought of, because it is this consciousness thatthinks about the past, thinks about the future,thinks about the present. But also this conscious-ness experiences all of the objects of the five senses:forms, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensa-tions. However, it does not experience them in thedirect and clear manner of the five senseconsciousnesses themselves. What happens is that

following the generation of one ofthe sense consciousnesses, amental replica or image of thatparticular sense consciousness isgenerated, which is called a men-tal consciousness. This mentalreplica is not a direct experience,but has been called a vague ap-proximation. And this vagueapproximation forms the basis forthe subsequent conceptuality ofrecognizing it as such and such, orgood and bad and so on, whichensues. Therefore, while it doesbase some of its content upon thefive sense consciousnesses, thesixth consciousness itself does notrely upon a particular organicsupport like a sense organ. It�sgenerated following any of the five

and can also arise under other circumstances. Itrelies essentially upon cognition, or cognitive capac-ity itself, as its support.

Now, the five sense consciousnesses arenonconceptual, which means that they can onlyperform their specific function of mere experience.So the eye consciousness sees forms and the earconsciousness hears sounds and so on. Therefore,they can only experience the present, and onlydirectly. Now, the present and the past and thefuture are important concepts which are discussed

arisings or mental formations. And the way we lookat or classify the mind varies a little bit betweendifferent traditions.

In the context of the shravakayana, or thevehicle of the hearers, then it is said that mindconsists of six types of consciousnesses. These aresix types of consciousnesses that we experienceclearly, that manifest clearly in our experience. Inthe mahayana traditions we generally talk abouteight types of consciousnesses, which are those sixtypes of consciousnesses which are experiencedclearly plus another two which are constantlypresent and are never particularly clearly manifest.

With regard to the six consciousnesses, the firstfive of these are what are called theconsciousnesses of the five gates, the five gatesreferring to the five senses. Thefirst of these is the eye conscious-ness. The eye consciousness is thatwhich experiences as its objectvisual form, various shapes andcolors and so on, on the basis of orrelying upon the organic support ofthe physical eye. And that is theeye consciousness. The second is theear consciousness, which in muchthe same way experiences its ob-jects, which are the various sounds,pleasant and unpleasant and neu-tral and so on, through the mediumof relying upon its organic support,which is the ear. The third con-sciousness is called the nose con-sciousness, and it experiences vari-ous smells as objects, through theorganic support, or relying upon theorganic support, of the nose. The fourth is thetongue consciousness, which experiences varioustastes�sweet, bitter, sour, salty, and so on�relyingupon the organic support of the tongue. The fifthconsciousness is called the body consciousness ortactile consciousness, and the objects of this con-sciousness are all forms of tactile sensation.Whereas the other four organic supports werespecific sense organs, which primarily perform theirspecific functions, here the organic support is theentire body, all of which can detect or feel a tactile

SHENPEN ÖSEL 17

a great deal in the study of Buddhism. The present,of course, ceases immediately, and by ceasing, itbecomes the past. The future, which does not yetexist while it is the future, occurs, at which point,once it has occurred, it is not the future any morebut is the present. So the present, this term �thepresent,� or �now,� really refers to an instant inbetween the past and the future. And this is all thefive sense consciousnesses can experience. Youreyes, for example, can only see the present. Youreyes cannot see what is past nor can they see whatis the future. And not only that, but your eyescannot estimate or evaluate the present. Your eyeconsciousness only sees shapes and colors. It doesnot, in itself, recognize these various shapes andcolors as some �thing� or another, does not concep-tualize about them. Now, all of thefive sense consciousnesses are, inthe same way, nonconceptual. Thesixth consciousness, however, isconceptual, because it recognizesthings, it brings concepts to bearupon experience and therebyconfuses the experiences with theconcepts about those experiences,including the confusion of apresent experience with a pastexperience of something similar orapparently the same. So the sixthconsciousness, which is conceptual, not only experiencesthe present but brings the concepts of the past and thefuture to bear upon this present experience.

Those six consciousnesses are called unstable orfluctuating, which means that they are suddenlygenerated by the presence of various causes andconditions, and then they cease when those causesand conditions are no longer present.

The other two consciousnesses in the list ofeight, which are the consciousness which is themental afflictions and the all-basis consciousness,are by contrast referred to as constantconsciousnesses, which means that they are notsuddenly generated and then suddenly ceasing;they are always present. However, while they arealways there, they are not clear or manifest orobvious, like the first six. They are always there,but they are very hard to detect. The first of these

This fundamentalfixation on a self. . . will be thereuntil you attainthe eighth level ofbodhisattvarealization

two, the seventh consciousness or the consciousnesswhich is the mental afflictions, or klesha conscious-ness, is the innate fixation on a self that we allpossess or that afflicts all of us. It�s this innateassumption of �I.� Now, this is present whether werecollect it or not, whether we think of it or not,whether we�re conscious or not, whether we�rewalking or sitting. No matter what we�re doing,this persists. Now, sometimes, when we think �I,�we generate a literally conscious fixation on a self.That is not the seventh consciousness. That is thesixth consciousness�s version of fixation on a self,because that is sometimes there and sometimesnot. The seventh consciousness, this fundamentalfixation on a self, is always there, and in fact it willbe there until you attain the eighth level of

bodhisattva realization.The eighth consciousness is

called the all-basis consciousness,and it is the mere cognitive luciditywhich is the fundamental basis forthe rest of the functionings of mind.And because it is the basis for all ofthe rest of the mental functioningsor activities, it�s called the all-basis.Now, it is on this basis that all ofthe habits of samsara are piled:habits of karma, of kleshas, and soon. And through variations in one�s

habituation�the habits that you accumulate�then various results arise. Through various types ofhabituation, then you tend to cultivate more virtu-ous and fewer unvirtuous states of mind, or theother way around; and through all of these varia-tions and habituation which produce habits thatare laid onto or piled onto the all-basis, then youexperience the world in your own particular way.Various appearances arise, and you experience thefluctuations; and to the extent you experiencefluctuations in the degree of mental affliction, youexperience fluctuations in your intelligence andyour compassion, and so on.

Now, the all-basis, together with the otherseven�all of these�are what are called the eightconsciousnesses. And through the practice of medi-tation in particular and the practice of dharma ingeneral, gradually these are transformed into what

18 SHENPEN ÖSEL

are called the five wisdoms, which means that theirbasic nature is revealed. And the full revelation ofthese, the full transformation of the manifestationof these from the samsaric manifestation of theeight consciousnesses into the pure manifestation,is the five wisdoms. The full and final extent of thisis buddhahood.

Ultimately, of course, the eight consciousnesseshave to be completely transformed into the

five wisdoms. But when we�re beginning to practicemeditation, and in particular tranquility andinsight meditation, which of these eightconsciousnesses are we actually using? The fivesense consciousnesses are outward directed, whichis to say, they can only perform their specific,nonconceptual functions of seeing, hearing, smell-ing, tasting, and experiencing tactile sensations,respectively. Therefore, they cannot be used in anintentional act of meditation. The two constantconsciousnesses, the consciousness which is themental afflictions and the all-basis consciousness,are, of course, ultimately things we want to get ridof. But we don�t need to try to get rid of them now,principally because we cannot get rid of them now;we can�t even detect them directly. So they, also,cannot be used in the process of meditation.

The only consciousnessamong the eight which fulfillsthe necessary criteria for being atool we can use in meditation,and also needs to be applied inthis way or it will continue to getmore and more confused�willcontinue to get worse�is thesixth consciousness, the mental consciousness. Thesixth consciousness is conceptual and, therefore,can support an intentional act of meditation. Thesixth consciousness also is that which generatesand experiences thoughts and all the various sortsof kleshas which are the contents of thoughts. Itcan be refined. While it is very coarse in its usualmanifestation, the sixth consciousness can besoftened; it can be refined.

So it is the sixth consciousness that actu-ally meditates.

Now, the way the sixth consciousness arises is

as a central mind surrounded, so to speak, bymental arisings. And the mind, the central mind, isthe cognitive clarity itself. And the mental arisingsare the various things that appear in the mind. Andthere are various lists of these. For example, thereare those that are always present in any inten-tional or volitional action, such as sensation, intelli-gence, intention, resolution, and so on. Then thereare those that are specifically virtuous, such asfaith and compassion, and those that are specifi-cally negative, such as spitefulness.

All of these arise, under various circumstances,together with the sixth consciousness. And which-ever of them arise depends upon the habituation ofthat particular individual.

Some of these can be either virtuous orunvirtuous; for example, sleep is one that can bevirtuous sometimes and unvirtuous other times.

Now, among these mental arisings, the onesthat we employ in the practice of meditation areones such as samadhi, or mental absorption, whichis the faculty of the mind�s remaining stable, with-out moving or changing; and then mindfulness orrecollection, which was presented earlier, and is thefaculty of not forgetting, or the faculty of recollect-ing what you are trying to do and what you aretrying not to do; and then alertness, which comes

along with mindfulness, as well asintention and, we would have to say,resolution or will, which is a furtherdevelopment of intention.

Now, the way that you employthese in meditation is not to at-tempt to overpower or controlrigidly the sixth consciousness, but

to allow your mind to simply relax naturally. Andthe relaxation of the mind in this way is thebeginning of tranquility or shinay.

When you are meditating, you need to relax intoa state of stillness, which is to say where your mindis at rest, without impeding the mind�s clarity orlucidity. And, while you�re practicing, there willarise a variety of experiences. Some of them arelucid, some of them are not lucid. Among the expe-riences which will arise, there are some that indi-cate defects in the meditation. One of these istorpor, which has two varieties. There�s what we

So it is the sixthconsciousnessthat actuallymeditates

SHENPEN ÖSEL 19

could call torpor itself, and there�s obscurity, whichis a further development of that. Torpor is theabsence of clarity, the absence of any cognitivelucidity in the meditation, and obscurity is evenbeyond that, where there�s a thick dullness. Now,the problem with torpor and obscurity is thatobviously they bring about the disappearance ofmindfulness and, therefore, of alertness as well.

Another problem that can arise in meditation iscalled excitement. Excitement is when the lucidityof the mind becomes too intense and becomesconceptual. And, therefore, the mind generates lotsof thoughts�past, present, and future, and so on�that are so many and so intensethat you can�t stop them or letgo of them. Now, this can beeither a pleasant or an unpleas-ant excitement. It could beexcessive excitement in beingtoo happy or too enthusiastic. Orit could be a feeling of deepunhappiness or discontentment.In either case, the result is thethoughts which distract you.

Now, there are, obviously, alot of things that can go wrongwith meditation, but basicallyall of them are included withinthese two types of defects, torporand excitement.

There are three things you can do in general toget rid of either of these defects. And the three thingsare what we could call external changes, visualiza-tion, and using motivation.

If we look at torpor, first of all, using motivationto get rid of torpor can be effective, because thenature of torpor is a mental dullness which is, tosome extent, a lack of motivation. So, therefore,recollecting the qualities of the dharma and of theBuddha and recollecting the benefits of meditationcan sometimes promote the clarity that will cutthrough the torpor.

And then, secondly, using external changeswould be, for example, making sure that the placein which you are meditating is sufficiently illumi-nated�possibly turning up the lights�and makingsure that you�re not too hot, that you�re not over-

A lot of things . . .can go wrongwith meditation,but basically allof them areincluded withinthese two typesof defects, torporand excitement

dressed, and that your body is cool enough.Then with regard to visualization, when you are

experiencing torpor, you can visualize in yourheart, which is to say in your body at the level ofthe heart, a white, four-petalled lotus, which isvery, very bright and brilliant; and in the center ofthis lotus is a tiny white sphere of light. And then,having visualized that, you think that the sphere oflight comes up through the center of your body andshoots out the top of your head. That visualizationis very helpful for dispelling torpor.

Then there are three corresponding ways towork with excitement.

Generally speaking, excitementcan come from either pleasant orunpleasant mental states. You couldbe excited or agitated by guilt, forexample, or you could be agitated orexcited by something that makesyou very happy, that you can�t stopthinking about. In either case, thebasic problem is that the thoughtskeep coming back again and againand again, and you can�t get rid ofthem. Generally speaking, the wayto work with motivation here is tocultivate a little bit of sadness.Sadness is very helpful for dealingwith excitement. So you could con-template the defects of samsara, the

sufferings of the lower realms, impermanence,and so on. Generally speaking, anything thatlessens clinging, fixation, and attachment willhelp with the problem of excitement.

Now, the second way to work with it is usingexternal changes in the environment. And,whereas, when you were working with the problemof torpor, you wanted everything bright and cool,and you wanted your physical posture as erect aspossible, here you can actually slump a little bit,and it may help calm you down. And, especially, theroom in which you meditate should be not toobright, if you�re suffering from excitement, and youshould make sure you�re warm enough. You shouldbe at least warm enough when this problem occurs.

And, then, thirdly, as for visualization, in thiscase, you visualize that this four-petalled lotus in

20 SHENPEN ÖSEL

your heart is jet black in color, and the little sphereof light in its center is also black. And this time,instead of going up, you think that it, the littlesphere of light, drops down from the lotus, goesstraight down the middle of your body, out of thebottom, and keeps on going down, intothe ground; and that will help verymuch to calm you down.

So that was a little bit about medita-tion, and if you have any questions,now�s the time.

Question: You mentioned about the sixthconsciousness. Its support is non-organic.It doesn�t have any fixation the way theprevious five senses do. In what way doesit fixate on cognition, and what role doesthe brain have to play with mind?

Rinpoche: Well, all of theconsciousnesses rely, to some degree,upon the brain as an organic support inhow they operate. But the sixth does notparticularly do so more than the others. The reasonthat the sixth is not said to have a specific organicsupport is that the sixth consciousness arises toinvestigate and label the immediately precedingconsciousness. Now, the immediately precedingconsciousness could be one of the five senseconsciousnesses or it could be another sixth con-sciousness. For example, suppose you have an eyeconsciousness of various shapes and colors. Thenthat ceases. Immediately upon its cessation, a sixthconsciousness will arise that will attempt to distin-guish and recognize and then label and have opin-ions about what the eye consciousness saw. In thesame way, after an ear consciousness occurs, inwhich maybe you heard someone say something,then immediately after that ear consciousnessceases, a mental consciousness will arise which willattempt to recognize the words, if they were words,and then to do such things as decide, well, �Werethey true, or were they false,� and so on. The samething happens when you smell something, whenyou taste something, when you have a tactilesensation; immediately after the cessation of thesense consciousness, the mental consciousness

arises and starts to investigate. Now, this can occuralso with and subsequent to a mental conscious-ness. In other words, when a mental consciousnessceases, then subsequently, immediately afterwards,another mental consciousness will arise that will

have opinions about thatprevious mental conscious-ness. That�s how a thought isgenerated on the basis of aprevious thought, for ex-ample. It�s for this reasonthat in abidharma, the men-tal consciousness is said torely upon the cessation of aprevious consciousness as itssupport. So its support is notorganic the way it is for thesense consciousnesses. It�snot that it�s totallyuninvolved with the senseconsciousnesses; it�s that thesupport for its specific func-tion is the cessation of the

previous consciousness which makes up its sub-ject matter or object.

Question: . . . We tend to develop our habits . . . asmall child on a playground takes the toy awayfrom the other one, and then as we grow, our habitsbecome more sophisticated, and we learn morepoliteness, and so as we advance toward adulthood,our structure of habits begins to lie one on top ofthe other, like layers of an onion. But I�ve noticedthat when I�m under tremendous pressure, mysophisticated adult habits will very often revertback to more childish responses, and I�m curioushow, as we advance on the path of meditation, wedispel all of that. Do we take the onion layers backaway one by one and move towards childhood, or isit some other mechanism?

Rinpoche: It�s true that there is a directness andsimplicity about the behavior of children in general,but the simplicity is foolish. Children are not simpleand straightforward and direct because they aremore virtuous but because they don�t know anyother way to be. They don�t understand tact or

The variationsamong children,like thevariationsamong adults,depend uponthe previoushabits whichthose childrencame into thislife with

SHENPEN ÖSEL 21

of even placement, in the sense of actual meditationpractice, but it is mindfulness and it is helpful.First of all, and most obviously, the more mindfuland alert you are when you�re working, the betteryour work will be. But the way to use this in medi-tation practice is that, if you actually practicemeditation, which is to say allowing the mind torest evenly, as was explained, and in that context,intentionally apply mindfulness and alertness, andcultivate non-distraction, then in post-meditation,by maintaining this type of natural mindfulnessthat arises when you�re working or in other post-meditation activities, you�ll very much support thepractice of meditation. But meditation does have tobe actually practiced.

Question: I�m wondering, how does creating a newmental formation, such as visualization, removeother mental formations such as samskaras, and isit a process of suppression, weakening, or can itcompletely eradicate those samskaras?

Rinpoche: Well, first of all, there isn�t really sucha thing as a new mental arising, in thesense of a new type. According to thecommon lists, the usual number offifty-one types of mental arisingsincludes all the various types of thingsthat can arise within the mind. Andthese are all of the various sorts ofthings which are brought together, or,say, brought around, introduced, bythe fourth aggregate, of formation,which in this case refers to mentalformations or mental arisings. Now,these can be both virtuous andunvirtuous, and they can be neutral,and so on. So in a sense, this aggre-gate is that which performs a lot of thefunctions of samsara. But the nature

of the aggregate itself is not inherently samsaric, sotherefore it can be transformed; and the transfor-mation of this fourth aggregate of samskara orformation consists of the increasing of the usefulmental formations, the ones that are necessaryand/or useful, and the letting go of the useless orcounterproductive ones. And, as this process goes

politeness. However, this can vary a great dealamong children. Some children are very cleverindeed, from early on. Some children are veryselfish; some children think only of others. And thevariations among children, like the variationsamong adults, depend upon the previous habitswhich those children came into this life with. Now,while it�s true that, in certain types of crisis, we canforget some of the habits we�ve accrued in oursocialization as adults and revert to our behavior aschildren, but this is not what happens when youpractice meditation. Because what meditationuncovers or reveals is not your habits from earlylife but the inherent lucidity that is what yourmind is, fundamentally. And this lucidity is yourbasic intelligence. And as it is revealed, and as itintensifies, your wisdom, in a practical sense,increases. You become more sensitive to what needsto be done. Of course, you become less deceptive,and so on, but your truthfulness is not based onself-interest; it would be based on a lack of competi-tiveness, of arrogance, and so on. All of the inherentgoodness in your mind starts to reveal itself, andyour spitefulness and so ondiminish.

In general, our thoughts serveto obscure and suppress ourinnate wisdom and our innatequalities. And, as you let go of theconfusion of thought, this innatewisdom starts to reveal itself, itstarts to rise up to the surface.And as it reveals itself, yourunderstanding of things growsaccordingly.

Question: Sometimes, whenI�m working, I�m very focusedand very alert and very awareand very mindful. Not always,but sometimes. And my question is, can that be, oris that a form of meditation, or can it be made aform of meditation, and do you have ways to en-hance that, or recommendations on how to enhancework as meditation?

Rinpoche: Well, this is not meditation in the sense

What meditationuncovers orreveals is notyour habits fromearly life but theinherent luciditythat is what yourmind is,fundamentally

22 SHENPEN ÖSEL

on, then gradually this aggregate is transformedinto what is called the wisdom of accomplishment.And, when this is completed, this is the transforma-tion of all forms of attachment and aversion anddeception and so on. All of this stuff is transformedinto a tremendous capacity to accomplish anything,to get anything done in a very practical way.

Now, in general, the meditation upon deities, ofcourse, is connected with this and all kinds oftransformation, but not in particular with workingwith mental formations alone.

Question: Rinpoche, this morning, you talkedabout tonglen, taking and sending. And, as far as Ican remember, you said that, when we practicetonglen, we didn�t necessarily take part in or wereinvolved in the conditions of suffering that we weretaking in�the suffering of other people that wewere taking in. If we�re not involved in the condi-tions, which I think is like causeand effect, then how can webecome involved, or how can weparticipate? How can we becomenon-dual, if we have nothing todo with those conditions? Couldyou say a little more about that?

Translator: I suspect this issomething in the way I trans-lated it. It sounds likedoublespeak on my part, if it�swhat I remember. I�ll check. Ithink it�s me, not him, but let�sfind out.

Let me say what I remember Rinpoche saying.What I think he may have said that for was that,although, when you�re practicing taking and send-ing, you actually generate the intention to take onthe sufferings of others, you will not actually expe-rience those �sufferings.� And I said �conditions��Iremember saying that, but I don�t remember hissaying that. But I can ask him.

Translator: Well he said he did say conditions, butI think he�s just covering up for me.

Rinpoche: The point is that the distinction that

was being made, in any case, was between theintention to take on the sufferings of others andactually experiencing the sufferings of others.When you�re doing the meditation, you actuallythink, �May I actually take on the sufferings ofothers; may they not have to experience them; mayonly I have to experience them.� And you generatethat intention as vividly and as genuinely as youcan. But it is impossible. You cannot experience thesufferings of others. Because experience is entirelyindividual. And experiences may be similar, butthey cannot be shared or transferred. Anindividual�s experience of suffering or any otherkind of experience comes from that individual�saccumulated karma and habits. And, if you havenot accumulated the karma and habits to have acertain experience, you cannot experience it on thebasis of somebody else�s accumulation of karma andhabits. So, in fact, you cannot actually take the

experiences of others away from themand experience them yourself. How-ever, it is meaningful to generate theintention to do so, because by gener-ating the intention to experience thesuffering of others and to give themall of your happiness, then you arecultivating an attitude which seesothers as much more important thanyourself, which is a very powerful anddirect contravention of our mostdangerous and negative habit. And,because you�re cultivating the inten-tion to take on the sufferings ofothers, while you cannot literally do

that, the generation of that intention will cause youto help them a great deal. So it does benefit others.But you can�t literally experience their suffering.

Question: Rinpoche, first of all, thank you forcoming to Seattle. My question is also about ton-glen. Do you think that there should be any prereq-uisite experience before practicing tonglen, such asmeditating for some length of time or some experi-ence with shinay, or taking the refuge vow ortaking the bodhisattva vow?

Rinpoche: Of course, it�s good that people have

In fact, youcannot actuallytake theexperiences ofothers away fromthem andexperience themyourself

SHENPEN ÖSEL 23

the teachings; you�re supposed to pray for all beings�but it�s natural, when our lama is sick or our motheris sick or whatever, we want to benefit that person, sowe�re doing practice just for that person, not with ourmeditation in mind whatsoever. So would we do Tarapractice? Is that more appropriate at that point?

Rinpoche: The answer to your first question isthat it�s not possible to really take on the karma ofanother being, and that when lamas or gurusappear to do so, of course, they have the intentionto do so, the wish to do so. They wish they could,you know. And because they wish they could, thenthey may sometimes appear to do so, largely be-cause of the attitude of people around them. But, infact, they are not really literally taking on andexperiencing what would otherwise be the sufferingof others. Not literally.

The second question: It�s acceptable to do tonglenas a practice in order to benefit another specificperson or specific set of persons, provided that yourintention is really to benefit them�provided thatyou�re not just doing it, and cultivating it as sort of anattachment. But if you�re actually doing it to benefitthose people, of course, it�s fine.

So we�re going to stop, and we�ll conclude withthe dedication.

some preparation, such as meditation experienceand the vow of refuge and so on, before they prac-tice tonglen. But there�s no necessity that theyhave any such prior experience or commitment. Ifsomeone who has not taken the vow of refugepractices tonglen with pure intention, then theywill still increase their love and compassion. They�llstill be able to cultivate the desire and intention tobenefit others. With regard to the need, in particu-lar, for a prior experience of shinay, then, if some-one who has very good shinay practices tonglen,then, of course, it will be very effective. But even ifsomeone who doesn�t have very good shinay�someone who hasn�t practiced shinay very much�practices tonglen, it will still benefit them. So,because there�s still benefit, it�s not appropriate tosay there is such and such requirement.

Question: Rinpoche, getting back to the previousquestion, about tonglen, I have two questions thatarose from that. One is that it�s sort of�I�ve neverheard it in teachings per se, but it�s commonly talkedabout that a lama takes on the karma of his disciples;that�s why he�s sick or whatever. So is actually takingon the sickness�is that mostly for enlightened beingsonly? And, secondly, when we want to benefit aparticular sentient being�maybe it might not be in

Rinpoche with the group that attended the Seattle teachings

Phot

o by

Rys

zard

K. F

rack

iew

icz

24 SHENPEN ÖSEL

His Holiness The Very Venerable Lord of Refuge Kalu Rinpoche

Phot

o by

Don

Far

ber

SHENPEN ÖSEL 25

Taking RefugeBy His Holiness The Lord of Refuge Kalu Rinpoche

At this time we are exceedingly fortunate in that not only have weall obtained a precious human body, a precious human birth, butbased upon this, we have actually entered the door of the dharma,

have given rise to faith in the teachings, and have actually practiced them.The entrance into the door of the teachings of buddha-dharma is the

taking of refuge in the three jewels [Buddha, dharma, sangha]. If one doesnot go for refuge with faith to the three jewels, but rather goes for refuge toworldly deities [i.e., unenlightened deities], and is unaware of the qualities ofthe three jewels, then one is not a practitioner of buddha-dharma.

Therefore, it is said that the root of the Buddha�s teaching is faith inthe Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha. Because without faith in these,one will have no conviction about the validity of the teachings, and, lack-ing this conviction, as well as lacking conviction about the qualities of thesangha, one will be unwilling or unable to study the teachings. Even if onedoes study them to some extent, it will be like the games of children.

The word in Tibetan for the three jewels, könchok, literally means �rareand supreme.� The first syllable, kön, means �rare.� It points to the fact thatthe Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha are like the rarest of diamonds inthat only someone with the [necessary] karmic connection and the necessarymerit will even hear their names, let alone be able to develop faith in themand receive teachings from them. The second syllable, chok, means �su-preme� or �best,� and again, like the diamond in the example, the threejewels are supreme in that only by relying upon them, can all of one�s needsand wishes as well as ultimate freedom be accomplished.

The essence of the mind is emptiness; the nature of the mind is actu-ally the indivisible union of emptiness, clarity, and awareness. The name

26 SHENPEN ÖSEL