Shapes - Manchester Community College · 2015. 2. 12. · The Literary and Art Magazine of...

Transcript of Shapes - Manchester Community College · 2015. 2. 12. · The Literary and Art Magazine of...

The Literary and Art Magazineof Manchester Community College

Spring 2014

The editors of Shapes invite you to submit your poetry, prose and artwork for consideration for publication in the spring 2015 is-sue. Poetry should be typed and single-spaced. Please keep a copy of any poetry or prose that you submit. We promise to handle all artwork with care.

Submit written work to:Steve Straight (English Dept., Tower 507, 512-2688)Patrick Sullivan (English Dept., Tower 509, 512-2669)or to the Liberal Arts Division secretary.

Submit artwork to Maura O’Connor (Graphic Design Dept., LRC A229, 512-2692)

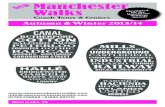

ShapesShapes

Faculty Advisors, Editorial:Steve Straight Patrick Sullivan Mariana DiRaimoDesign:Maura O’Connor

is Manchester Community College’s art and literary magazine. Contributors are all members of the MCC Community.

photo by Alyssa N. McDonald

Spring 2014

Shapes

art by Sarah Loftus

Table of Contents

cover design by Maura O’Connorart by Taylor Hastings

art by Jeffrey Winot

1

Beer Can by Richard Chotkowski page 2Tweety by Richard Chotkowski page 4Blindsided by Joan Hofmann page 5 First Car by Richard Chotkowski page 6Days: Then and Now by Joan Hofmann page 8 Modern Art by Conor Breen page 10You Can Carry Me Home Nowby Heather Strickland page 11The Day the Sky Fell by Isabella Kiss Tonski page 12The New Sermon by Richard Chotkowski page 22 Below the Surface by Joan Hofmann page 28Firewood by Richard Chotkowski page 31A Field of Wildflowers by Heather Strickland page 32Keepers by Joan Hofmann page 33

Grading Essays for Comp Classby Michael DiRaimo page 34Let There Be Light by Richard Chotkowski page 36So Much Trouble in the Worldby John Stanizzi page 39Westward Eastby Stephen Campiglio page 40Wilderness Program by Valerie Rizzo page 42You Bring Out the Mad BlackWoman in Me by Natasha Davis page 44The Life of a Street Musician by Matt Prince page 46Deleted Scenes by Steve Straight page 48Job’s Wife by Jeanine DeRusha page 50

2

photo by Leah Broadwell

art by Rachel Rubenbauer

3

Richard Chotkowski

Beer CanThis beer can I’m looking at Devoid of commercial symbolism Just a cylindrical shape of bubbling rust With two triangular holes punched through an endOne for air, one for beerOnce provided an adequate amount of thirst quenchingSchlitz, Narragansett, Pabst, SchaeferOr any brand that was popular Fifty years agoWhen a young guyUsed a church key to get atThe refreshing bubbly liquid inside.Probably on a typicalIt’s-not-the-heat-it’s-the-humidityConnecticut kind of day,A Saturday afternoon.The day off from making tools at Stanley Works,He took his gal to Stanley ParkWhere they had a picnic.Listened to that new Marvin Gaye songThrough the tinny speaker of a Japanese Transistor radio dialed in to WPOP.They ate some fried chicken and crumbly pieces Of apple pie her mother madeAnd he pried the triangular holesInto a couple cans of beerFrom the heavy metal cooler That he carried, along with a blanket and the radio.She carried the picnic basketTo the back of the parkWhere the old trap-rock fireplacesBuilt here and there throughout the woodsDotted the landscape like tiny castles

And when they packed for homeIn the late afternoonAnd walked back to their Buick LeSabre station wagon

One of the empty beer cans stayed behind, abandoned or escapedAnd now some old guy, me, walking his dead father’s blind dogSteps into the overgrown woods towardOne of the piles of rocks that was once a fireplaceTo take a leak and sees, Poking through the dead leaves,What was left behind fifty years beforeRusty, crumbling and worthlessBut so full of value.

4 5

art by Mary Ellen O’Donnell

photo by Karen Fox

Richard Chotkowski

Tweety

Tweety was my father’s Chihuahua.She’s still going at eighteen.It’s my father that diedand left her behind.

Her eyes look likeblack marbles coveredwith nearly opaque white cataracts.

Her ears stand perfectly straightbut if you shout her name from three feet awayshe can’t hear you.

Her nose still wiggles and twitcheshigh in the air like a starter pistolor low to the ground like a vacuum cleaner.

Tweety still has no concept of good manners.She sniffs and swaps scents with the pointer next door,sleek, virile, male, and oh, so keen on her.Then she’ll spread her hind legs and arch her back,squeeze out a Jimmy Dean in front of him, and turn and saunter away.

When she isn’t trying to open her collapsed esophagusor isn’t walking head-first into a fire hydrantor isn’t swaying sideways trying to get her balanceafter sleeping for two nights and a dayshe looks almost show ready.

Head high, tail erect, chest out, stomach inready to take on the worldwith the same fascinationthat she had in 1995.

Joan Hofmann

Blindsided

April is the cruelest month. ––T. S. Eliot

That April afternoon while Southern sunlightstreamed down into the backyard, it was just

weeks before she passed. Knowing she’d be leaving,in that light my son and I hung prayer flags inevergreens by stalks of iris and mounds of pale pansies.

We strung colored squares—red, emerald, canary, royal blue—with hope. Promise even. Buddha, we called,bless our family, and give Colette a peaceful passing.

We roped the prayer cloths aloft to catch the faint breeze,to waft gentle blessed air toward her bed to sweetlytake her last breath away.

Barely smiling, thin-lipped and long-faced, we huggedas mother and son to bargain a deal with Buddha,confident our call would be heard and heeded.

Dying can take a long time. Though her passing neared,she weakened into May, waiting as the bright flagswaved on. We wondered: Where was Buddha’s hand?

We asked: Why a deaf ear to us? To her?—a woman whopleaded, Why is this taking so long? I was a good girl.

art by William Harper

6 7

Richard Chotkowski

First Car

She was an Oldsmobile Ninety-Eight andall cars were females andshe was built for the times––cheap gas and dirty air––bolted sheets of green steeleighteen feet long, four thousand poundswith an engine the size of a Priusthat seared the atmosphere in her wake.We were sixteen and so was she.Peach-fuzz and rusted ironoccupying the same space and time.Her interior was a grand hall,plate-glass windowstrimmed in chrome,cranked by muscle.She didn’t have seatbeltsand we didn’t have a license between us.But it was 1972, a yearto have floor mats stainedwith Quaker State and Colt 45reeking gloriously noxious vapors,arousing adventure on a budding spring day;Oh Behemoth of yoremechanical dinosaurwith a working radiothat played Highway Star or Radar Love.Ride, Captain, Ride.

Me and Kush split her down the middle.Twenty-five dollars apiece.We earned it running ridesfor a traveling carnival.Five bucks a night.

Kush ran the Merry-Go-Round.I ran the Tilt-A-Whirl, andI could really spin ‘em,

if that’s what they wanted.Like the three fat chickswho wanted it bad.I got ‘em spinning so fasttheir cotter pin broke and theyflew over backwards,drunken game henslaughing at the summer sky.

photo by Lewis LaPalme

photo by Jayni Jedlicka

8 9

art by Bonnie McCaffrey

art by Rachel Rubenbauer

Joan Hofmann

Days : Then and Now

I

I hear Mom’s voice: Hey diddle diddlea cat, the fiddle, the cow jumped over the moonthe dish ran away with the spoonbaby rocked in the treetop wind blowingdickie birds flew from the hillas itsy-bitsy spider climbed the waterspoutand Jill tumbled after, taking a spill.

II

Mom taught me my numbers and lettersthough I also loved outdoorsso we split our time, but I learnedthe ups and downs and ins and outsof letters and life-lessons at her hand,foot and knee, while school teachershad us write flowery spans of OOOOsand PPPPs across page after pageof handwritten cursive in labored Palmer.

III

We laughed, her finger circlingtickly on your knee, or cradling my chinwith buttercup to prove butter-love,in later years graduating to jacks or dollsor crazy-eights, hopscotch and jump rope,sometimes flower or berry-picking, firefly-catchingwatching bugs, birds and, always, the skywhere I now look for her nightlyas I imagine us rowing gently down a stream.

10

art by Anonymous

art by Chelsea Lundbergart by N. Goodrich 11

Conor Breen

Modern Art

“Art is anything you can get away with.” ––Marshall McLuhan

I’ve gotten away with a lot,but I’ve never considered any of it art.Crayon on the walls,hot chocolate on the ceiling,ice cream on the floor.I’ve caused more of my parents’ griefthan I’d like to recount.

Just thinking of all the thingsthat I never got in trouble for,I can’t call a single one my “masterpiece.”My mother never walked through the hall yelling, Whose art is in the living room?I wasn’t Andy Warhol;it was just a bowl of Campbell’s Tomato Soup,spilled on the carpet.

Heather Strickland

You Can Carry Me Home Now

In the French village of Sarpourenx the mayor has declared that anyone without a plot at the local cemetery will be “severely punished” for dying.

Monsieur, you cannot die here! What do you mean? I’ve waited seventy years, in a field of daffodils blowing in the loving wind.

I’m sorry, but you must pass on elsewhere. But I’ve shed blood upon your doorstep with the clanking of the militia. I’ve wasted my money away for your greedy tariffs. I have worked this soil for eons, after my wife spoke about your beautiful hills and rolling blades of grass, the way your romantic language softened her heart.

But, you have not bought a plot of our land amongst the filled mausoleums. Yes, for I have but two pennies to rub together, moths have begun to take refuge in my sleeves. Your honor, I have no one to pay my living expense, my medication costs. My retirement fund has withered up from frequent drought: just ask my son.

However, this country has free healthcare. Yes, well in any case, death should be free as well. I’ve paid my dues. I am but a seventy-year-old widower who wishes to meet his wife. Hug her among the daffodils and lilies in my Sunday best. Today. In this town.

Monsieur, I will be forced to hang you for incompliance with the law. Yes, well, as swiftly as existence fills my nostrils, the Earth seizes my need for breath. So, s’il vous plaît, you must cut the cord this time.

12 13

Isabella Kiss Tonski

The Day the Sky FellYou know the story, the one about the chicken who thinks that the sky fell on his head. He runs around yelling, “The sky is falling! The sky is falling!” I’ve heard that story; but I’m here to tell you that it’s

nothing like the real thing, because I was there the day that the sky fell, and it’s nothing like the story.

The day before had been a typical day in the summer of 19--. A light breeze blew and the sun tickled your cheeks. It was one of those days that called you out-of-doors and held you captive in the magnificent sunlight. A perfect day for a boy of my size to start making his fortune, so I, along with my neighbor Frankie, started up a lemonade stand. By noon we had made one dollar off our product– which sold at twenty cents a cup. By suppertime we had a whole dollar and twenty cents. The two of us went home that night: Frankie with forty cents in his pocket and the rest jingling in mine, being as they were my lemons that we squeezed the juice out of. The next day we were going to do it again; we figured if we kept it up, by the end of the summer, we’d have enough money to buy a boat for sailing out on the lake. We had it all planned; our futures were upon us and we were ready.

But I didn’t account for what would happen next. There was no way I could have, really. Stuff just isn’t supposed to happen like it did. The next day, I went to set up our stand once more, eager to further my fortune. My pocket was full of yesterday’s profit, and my arms were full of that day’s bag of lemons. As I walked out the door to my front lawn, I stopped. The lawn wasn’t there. Well… I suppose it was; only I couldn’t see any of it. The lawn was covered with a flakey, blue mess that looked like someone had thrown sheets of colored construction paper all over the lawn and the sidewalks. The road looked the same, all covered in big flakes of blue. The picket fence outlining our front yard had pieces of the stuff skewered on each of the white points. In fact, everything in sight was covered with blue. When I had gone to bed the night before, all was normal. Noth-ing unusual was on our grass. I couldn’t remember any unusual looking clouds, or cracks in the sky warning us about what we would face the next day. It was as if someone had come in the night and created the flakey disaster I was now staring at. I looked up at the clouds. . .only there were no clouds. There was no weather. There was nothing.

The sky was . . . gone.

art by Justin Cowles

art by Lucy Sander Sceery

I screamed for my mother like I did whenever I had a nightmare. I needed her to come and tell me everything was all right. But the sound hissed out of my mouth, fell from my lips, and filled the bareness around me, my voice blending with the hum. Nightmares

are always worse when you have to face them alone. I looked for my neighbors. Their houses were there. Their mailboxes, their cars, everything was there, just like it should have been. Only, everyone had pieces of the heav-

ens strewn across their grass, caught in their trees, and stuck on their fences. But no one seemed to be around. Didn’t they care? I thought about calling the police or the fire department. But what did they know about fallen skies? For as long as I could remember, this had never happened. How was I supposed to know what to do? I was alone and desperate, so I did what any boy of my size would have done if given a situation such as mine. Carefully, I snapped a branch off the little piney shrub next to our doorstep. I poked the ground, or the sky, I guess it was, with the branch. Nothing hap-pened. No sound. No feeling. No sudden explosions. I edged one toe off the step and gingerly stood on what was once the sky. Again, noth-ing happened. Emboldened, I bent and picked up a piece of it; it was flimsy like a sheet of the daily newspaper that my father hid behind 14 15photo by Alyssa McDonald

Now, it’s hard to explain what nothing looks like, but I tell you, I saw what wasn’t there. The blue expanse that had been dotted with clouds and warm rays of light the day before was now nothing but emptiness. Above my head was an eerie vacancy that shouldn’t have been. Instead of sky there was ... sort of a hum, more a sound than a sight, something you felt but couldn’t touch. It was like there was a wild wind, but with no movement. It was like the sun’s glow on a blistering day, only without the warming of your skin. I looked up again, and realized with horror that it was the sky that was scattered on my front lawn. I leapt backwards onto the safety of my doorstep. The sky was on my front lawn, and in its place was nothing.

Somehow, the sky had fallen.art by Emily Albee

1716

each morning at breakfast, but soft like the pair of flannel pajamas that my grandma gave me on Christmas. It was thin like paper, but when I shook it, it didn’t crinkle, it didn’t rip. Next, I threw it as high as I could. It didn’t suspend itself back where it belonged. Instead, it floated noiselessly back onto the lawn, covering up the patch of green that I had exposed. It was like the sky didn’t want to be fixed. I ran inside, slammed the door, and leaned my back against it. After counting to ten with my eyes squeezed tight, I opened the door again, stuck my head out, and sure as anything, the sky was still there, right where it didn’t belong, scattered on the ground like confetti left over from a surprise party we hadn’t had. I bounded up the stairs, screaming for my dad. He was a smart guy, and I thought maybe he could fix the problem. Dads gener-ally know a lot about problems, and sometime they are able to fix them. “The sky! It fell. The sky is on the front lawn, Dad. I tried to put it back but….” “What?” my father asked, as he rolled over to face me. The space next to him on the bed was empty; the sheets were neat and tucked in. Mom was sleeping on the couch again. “The sky. It’s on the lawn. It’s all blue and everywhere and it feels like my pj’s from Grandma and it won’t go back up where it needs to!” He rolled the other way to look

out the window, but the faded, floral curtains were drawn shut. “Prob’ly just fog, son. It’ll pass.

Go on downstairs; turn on the coffee pot. I’ll be down in a bit.” I kicked the side of his bed with my slippered foot. “The sky fell down, Dad, and coffee isn’t gonna fix it!” My father sat up. “Yes, yes, I under-stand,” he said, as he tied his robe on and then rubbed his temples with the heels of his hands. I stomped down the stairs, scared and angry, and peeked out the window. Sure enough, just as I had said, there was no sky in the sky. I opened the front door and jumped on the mess that had found its way onto my lawn. I stomped around. I jumped on what was supposed to be the sky, angry that it wasn’t being the way it should. I heard my dad’s footsteps on the stairs; I flung open the door for him and cried, “Look!” He did. He blinked a couple of times and ran his left hand through his hair, like he did after having a fight with my mother. Then he chewed on his lip. “That’s the sky, Dad! All over our grass, just like I told you. That’s a whole bunch of sky!” My voice sounded hollow, like I was in a cave, only with no echo. My dad said nothing. He stood there, blinking his eyes, chewing his lip, and rubbing his gray-streaked hair. I rushed back into the house, hoping my mother would prove more helpful than my father. I began to bound up the staircase towards my parents’ room but turned and headed for the living room instead. “Mom? I need you to wake up! The sky fell onto the front lawn. Please get up.”

“It was like the sky didn’t want to be fixed.”

photo by Lewis LaPalme

news channel was talking about the weather like she did every morning. Only, that morning the weather forecast involved the sky having collapsed onto the earth.

I could see she was trying to be calm, just like my par-ents. Everyone was pretending that somehow tomorrow we’d all wake up and everything would be normal again. As if the next day she’d be saying the forecast would be back to sunny with a high of 85 and summer would be restored to its full glory. Footage of other neighborhoods with fallen sky strewed on the ground played across the screen. The weather woman smiled. It was then that I knew everything was not okay at all. “Sweetheart, come eat some breakfast,” my mother called from the kitchen. I heard her set a bowl down onto the table and pour juice into a glass. I didn’t want to take my eyes off the news report. I waited for her to announce that someone very smart had come up with a way to fix this situation. But I knew they hadn’t. I sat at the table, taking turns gazing at my steaming bowl of oatmeal and then out the window at the chaos outside. “It will be all right, don’t worry, sweetie,” said my mother, though I hadn’t said anything to her. She stood behind me, also looking out the window, running her finger through my messy hair. “It’ll get fixed. It will all be okay soon.” But I knew things weren’t going to be all right. I had heard that lie too many times before from my parents. Some things, once they are broken, can’t be fixed, no matter how hard you try. I knew that adults liked to act like they knew everything. That they somehow saw that it would be okay. At least that’s what they tried to tell me. But it wouldn’t. The sky had relocated to the front lawn. The world might as well be ending. At the time, I thought maybe it was. When things go that wrong you know that they just don’t find ways of becom-ing right again.

When I finished my breakfast, my mother said, “Sweetie, why don’t you go find Frankie and see if he wants to sell lemonade with you, like you 18 19art by Jason Duva

She rolled on the couch to turn and face me. “What, sweetheart?” “The sky, Mom. Please get up and see it. Dad’s outside looking at it. It’s messy.” My mother pushed her disheveled hair out of her swollen eyes. She sat up and slid her feet into her slippers and stood, putting her hand on my shoulder. “Okay, okay. Let’s go see it,” she said, as if she were playing along with a game. She shuffled toward the open front door with me. As soon as she got a look at the situation outside, she stopped. She made a little sucking noise as she drew air quickly into her lungs. Her mouth quivering, she walked out onto the step and stood next to my father. Her eyes kept getting wider or maybe her face was getting smaller. “I told you…it’s…the sky…” I tried to explain, hoping they would somehow, in their parental understanding, be able to make it right again. But neither one of them said anything. “Why is it on the grass, and what are we gonna do? Someone has to do something!” I yelled at my mute parents, aggravated that I was the only one feeling the need to take some sort of action. I was the kid! What was I supposed to do about it? Stuff like this wasn’t supposed to happen. The sky should always be the sky. Some things are supposed to stay nor-mal, every day of your life. But that day, on the front lawn of our home, the sky had decided

it wasn’t the sky anymore. Someone had to fix it, but my parents just stood gaping, waiting for it to right

itself, like somehow it would. My dad shook his head and stared at the sky-covered lawn. My mother stood beside him, not talking or perhaps too afraid to. She pulled her robe tighter. Again my father rubbed his hand through his hair. “Sometimes things are just out of our control, son.” “Everything will work out for the best, sweetie,” my mother said, again placing her hand on my shoulder. I pulled away and turned to stare at the two of them while they stared at the lack of lawn. “No! No it won’t work out, Mom! What don’t you understand? When the sky falls down, someone has to do something to fix it. I know it! Please, we’ve gotta do some-thing!” But, despite my plead-ing, neither of them did any-thing to make things right again.

My father was sitting in the living room, with the television on. In one hand he held his morning coffee and in the other he grasped the remote, holding on to it like it was the only thing he still had control over. Maria McCarthy from the

did yesterday. That was fun, right?” I gave her a look of nothing-can-be-like-it-was-yesterday. She gave me back a look of everything- is-just-fine. We both knew she was lying. She pulled out my chair and gave me a gentle nudge to get up. “Go on. Go get dressed and go see if Frankie is up.” On my way back upstairs I heard my father on the phone in the living room. He was still watching the news. “Are things all right where you are, Robbie?” he asked. Robbie was my older brother who was away at college. I ran upstairs before hearing any response. I knew things were a mess every-where.

When I stepped out my door, I tried to walk carefully. If by some miracle someone smarter than any of us did find a way to fix the sky, I didn’t want to be responsible for damag-ing it. I walked down the road to Frankie’s and passed three houses with sky-speckled lawns. I rapped on the door, and he answered, as if he had been waiting for me to come. “Mom and Dad said I can’t come out today.” “Oh,” I said, disappointed. My parents had sent me outside but his were keeping him safely in. “Did you see what it is like out there? Does it all look like this?” he asked. “All of it. The sky is everywhere.”

“I knew it!” “My mom wants us to sell more lemonade.”

“I’m not supposed to go any farther than this doorstep.” “I don’t think it’s dangerous or any-thing. I jumped on it a little. Wanna come over and sell lemonade?” “Okay, I guess.” He quietly shut the door behind him and made his escape. We walked back to my house and made a game of trying to step only on patches of cement or on tufts of green grass peeking out from beneath the fallen sky. We had played games like this before, pretending we were jumping from rock to rock, like adventurers crossing a rushing river, or carefully avoiding hot lava as we escaped an erupting volcano. Only this wasn’t a game. This was real. The games had been a lot more fun. We set up our stand right on top of the sky and mixed up our lemonade. Both of us sat there all morning. We didn’t have any custom-ers.

The following day the sky was still on the lawn. I think we had all hoped if we just waited it out long enough that we’d wake up one morning and it would be back to normal. But my father gave up hope faster than the rest of us. He was tired of being cooped up in the house watching the news, and he used the fact that we were out of milk as an excuse to leave. I tried to talk him out of it. I was wor-ried that if he drove on the sky it would dam-age it even more, and our hope of things going back to normal would be even smaller. “Dad! You can’t just go out and drive over the sky,” I warned him, as I spread my arms across the door to the garage. “It’s fragile!”

“We need milk” “We need the sky to be okay, Dad!” “There isn’t anything anyone can do, and we can’t just sit here waiting for it to work itself out. We need to go on living.” “What if you make it worse?” “We need milk.” He picked me up under the arms and lifted me out of his way. I watched out the window as he backed up the car and left the driveway. The sky was getting caught up in his tires and was making a sound like my bike did when I put playing cards in the wheel spokes. I watched him disappear down the road, rear-ranging the sky as he went. I chewed on my fingers as hope left my heart.

After the sky fell, nothing was ever really right again. Everyone gave up trying to fix it. We just had to accept that things weren’t going to be the same anymore. Everyone learned to live with the fallen sky, just like it was normal. Some days I remem-bered what it used to be like. But that was all it was: a memory. Any hope of things going back to the way they were before was long gone. My history textbook included pictures of what the sky used to look like before it relocated to the ground. Reading about what had happened was strange. We were all there. No one could forget.

Now I spend weekdays with my mom and every other weekend with my dad. My older brother has graduated and is married. Sometimes I see him on holidays. Frankie’s

family has moved away; we never did get rich off of lemonade.

2120photo by Maura O’Connor

I’m fixin’ to tell you it’s about more than that. And it’s more than rejectin’ material things. More than the richness of family and friends. What I wanna tell ya’ll about is responsibility. Now this is one of them words. It sounds like somethin’ you might not want to do. No matter. It’s waitin’ like a sunrise– or a sun-set.” Preacher Tindal raised his voice. “I am talkin’ about the responsibility to do the things you been told wasn’t right to do. I’m talkin’ about internal struggle. When you been told all your life something ain’t right, you believe it. The edu-cated call it indoctrination. And that is a proper sounding name for it. Undoin’ a doctrine you

been raised to follow should be mystifyin’ and tough as nails. But sometimes you got no choice. That’s the responsibility I’m talkin’ about.” Preacher Tindal knew his congregation. Their desires and considerations were common to his own. They were country folk with deep roots and beliefs. He spoke from a stack of hay bales topped with plywood. Stable enough. He hadn’t fallen yet. A full moon spilled down on the barn. Light beamed in through plank walls solid, strong. Brilliant stripes streaked from the “pulpit” to the floor. The preacher was calm, his thoughts collected. He counted a five-beat pause, looked across the shadows of the empty

barn, and then continued. “If you were to be born on the Sunday of next week and die on the Sunday following, well, that’s not much of a life, now is it? Likewise, if you were born in the days of John Henry and paid no mind to the world around you all this time, that ain‘t much of a life either. A lot of livin’ without meanin’.” His thick hair was tamed back from his forehead in a flow of gray. His black suit fit well but looked coarse, stiff as a breast plate. The pant legs creased sharply until they broke at his glossed but worn-thin shoes. He had perfumed him-self with honeysuckle oil. The scent, to Preacher Tindal, was the atmosphere of heaven. To the

chickens, pigs, and milking cow - inhabitants of the old barn - the preacher’s Divine gifts were gibberish, noise in the night keeping them awake. The preacher’s con-gregation would arrive later. This was his second

22 art by Emily Albee 23

Richard Chotkowski

The New Sermon

Preacher Tindal’s green eyes had an opaque quality - not cataracts - more like the waxy shine of millions of leaves giving life to August hillsides. Fed the hot light from above, shadowed and cool below with a changing breeze. The white parts were as unmarred as bleached pillow cases. The preacher was a com-fort to the individual gripped by the calloused nature of life. His hands gently squeezed quaking shoulders while his lips brushed the ear with comforting words

of reassurance, forgiveness, and tolerance. Anyone

who received Preacher Tindal’s individual attention felt as if a heavy object were lifted away. The preacher’s gift for personal succor was precious to the local community, and he knew this, of course. The entire afternoon and evening, every Sunday, was used to minister to one after another of his troubled folks. He was ap-preciative of his gift and thanked the Almighty for it. But his real enjoyment was in delivering the sermon. The preacher captured and held his flock with each exquisitely composed perfor-mance. Like an amusement park rollercoaster clacking along level

terrain, he would lead them in a steep slow climb into the blue sky, and after a short pause just below Heaven (where judgment must be inferred) they would plunge to earth, back to the heavy mortal challenge. When he finished a sermon he was shaky and sweat-plastered and as worn out as his congregation. Where the power really resided, in the climb, the hopeless fright of descent, or the brief moment at the apex, the preacher finally, just today, had discovered. “To many folks, the meaning of life strips down to the happy times they get to enjoy while on this wonderful earth.

photo by Jonathan Feld

24 25

rehearsal. He had written the ser-mon that morning; the pencil tip shattered many times during the frenzy. The pages were splotched with spittle as he transformed the Divine gusher of justifica-tion from mind to paper. It was more than a new sermon for the preacher—it was the seed of a new religion. “We all know the experi-ence of life rides on how you do your fellow man.” He held up a forefinger from each hand and

brought them toward each other. “Put it together with your re-sponsibility and listen here: let’s say you’re at the market buyin’ groceries, and you’re about to

add to your items for purchase a box of crackers from

the cracker aisle. Five beat pause. “A little old lady with a scowl on her face who, plain to see for anyone lookin’, she ain’t never had a kindly day, never a word of comfort or pity for the loneli-est soul, slides in front of you and grabs that exact same box of crackers you yourself were reach-ing for. Let’s say it’s the last box, the only box of crackers left there on that shelf, right out from in front of you. What in the world are you gonna do? Are you gonna

take a different box of crackers? Ya cain’t!” he roared. “Are you gonna turn the other cheek? Are you gonna let that sneaky shrew - why she’s probably hidin’ more dirty secrets than the Church in Rome - are you gonna ignore such behavior? If you do, it’s like

slidin’ backwards down a greasy log. “So how are you gonna start livin’ a better life? How are you gonna add to the fullness of your life? I’m gonna answer that for ya’ll. You ain‘t!” The words ricocheted. His fingers pointed forward one moment then straight up the next then stabbed straight down. “You could be breathin’ sweet air for a hundred and twenty years. And when it’s all over, that breathin’ will add

up to nothin’. What you gotta do, brothers and sisters, what ya’ll are gonna havta do is grab that box of crackers outta that selfish woman’s hands-- she needs you to do it--and if she looks at you the wrong way for it, let her know the path to righteousness

by using that box of crackers like the Almighty’s hand and just whack her square across the face with it. She needs the whackin’! “That, friends, will teach her the bitterness of the debt she places daily upon herself. Force her eyes open to more humble and selfless ways. You can help that poor woman avoid the torture of eternal damnation. This is the substance of a full life.Hallelujah.” If they had been physi-cally real, the flames of Preacher Tindal’s oratory fire would have incinerated the barn. The preach-er felt the need to recompose his emotional and physical man-ner. A rehearsal did not usually become quite so impassioned. However, these were different circumstances. To relate his new message of selfless responsibility required conviction. His thick hair was disheveled, and the honeysuckle scent was cut with the earthly stench of sweat. He would need fresh clothes.

He returned to the house, a Virginia mansion of yore. In past centuries there had been seven hundred acres of hill, valley, and agricultural field, a horse stable, a cotton gin, and a quarter mile lane of one-room slave cabins. The Tindal family once leased forty acres of the southeast corner, bounded on three sides

by the steep sandstone drops of the New River Gorge, to the state of Virginia to house a lu-natic asylum. The state built and operated the asylum from 1808 until 1859. It was closed after decades of nagging fear kept alive by regular escapes. Then came Lincoln’s War. The family lost slaves and cotton. The following three gen-erations of Tindals sold acreage to land developers until there was nothing left except the still-solid antebellum mansion, the barn, aslant with age, and the single acre the structures had been built on.

“Martha,” he called out upon entering the house. “Martha Love?” There was no reply. He continued. “I’m gonna need a fresh suit. I got this here one all sweated up and–” he saw the yellow paper on the kitchen table. It was from the county tax office. He already knew that. Across the face of the yellow paper, without regard to the legibility of a typed paragraph or the arithmetic below, printed in red: FINAL NOTICE. He considered many things, birth and death and his place in between those events, the truths and lies, the faces of good and evil, neither of which he now felt confident to recognize. The tip of his tongue slid back and forth between his upper and lower

front teeth. He considered biting down. He didn’t. He needed his tongue for the sermon.

Near the yellow tax notice was a messy pile of letters. They weren’t official. They were handwritten. They had been folded and refolded many times. The creases on some had the appearance of scissor cuts. They were scented also, but not with honeysuckle. They smelled of jasmine, Martha’s scent. Folks said that together, the preacher and Martha Love Tindal har-kened clear back to the Garden of Eden. While the preacher considered honeysuckle to be the scent of heaven, Martha pre-ferred the scent of jasmine for no other reason than she liked it. It was in her clothes, her pillow, her hats and the boxes she kept them in—and in the box where, that morning, he had found the pile of handwritten letters. Preacher Tindal looked down at his worn-out shoes, at the tile pattern etched in the li-noleum floor. The pattern spread before him to the heavy legs of the table and beyond. How many tiles were etched in this room? Certainly the number was finite. Perhaps he would count them someday. Not today. Today the scent of jasmine made his stomach lurch. He thought of the fresh suit he had come for

“That, friends, will teach her the bitterness of the debt she places

daily upon herself. Force her eyes open to more humble and

selfless ways.”

26 27

and the need to change quickly before his congregation arrived. He walked to his bedroom closet. His shoes slapped out the sound of flimsy soles with little height left to the heels. Three suits hung on wide oak hangers. Their scent caused him to close his eyes and smile. He took one, turned to lay it on the bed and change. He paused. He couldn’t lay the fresh suit on the bed. Martha was there. She was dead. Her body was in his way, and he didn’t want to move her. She could’ve had the decency to die someplace else, he thought. The rope tied around Martha’s throat cinched into the bluish flesh to such a depth it was almost hidden in the fold it created. The sight caused him to realize the choice to die while asleep in bed was not entirely hers. Still, for the choices she had made, she had atoned. He turned back to the closet and re-hung the suit. He clicked his tongue against the roof of his mouth and sought a solution. He had not touched Martha since the discovery of the letters. While in the throes of strangulation, Martha’s hands had flapped wildly as he lay

behind her–her back-side to his front-side, a posi-tion of intimacy on

another occasion–his face firm and red from effort, hers growing slack and blue. That had been be-fore the sun rose, before the birds sang. Now touching Martha’s flesh was not what he had antici-pated or desired. Ultimately, he knew, he had no choice. First he scented her with honeysuckle oil. From her face to her feet. He didn’t rub it in, just splashed her by flinging oil from his fingertips. Then he slid his forearms through the cold cav-erns beneath her stiffened arms. Her shoulders gave like rusted hinges. He straightened his legs and lifted. The back of her head brushed his face. He reversed and set her back onto the bed. He sprinkled her scalp area and also his own forearms. Again he lifted. Martha Love’s calloused heels thumped to the floor, whispered across the oak boards of the bedroom and across the kitchen linoleum. He bent her into a sitting position. She crackled and expelled a gurgle of rotten air. He set her into a chair at the kitchen table. He took a wooden stirring spoon from a drawer and used it to push the pile of handwritten letters across the table to his wife. He tilted her head downward to bring them to her attention. At the sink he squeezed a puddle of dish soap into the spoon, washed it with hot water then returned it

to the drawer. He stood over her. “I been meaning to tell you I found these. I was gonna surprise you with that pretty pink hat you’ve been wantin’ from Dotty Mae’s Dress Barn. I was gonna put the new hat in an old hat box so you could discover it by accident. You woulda been excited. You woulda laughed. I was gonna do that for you. “But I happened upon these here letters and poetry. Sinful muck! I suppose that was a real good hiding place for a time. That Jasper Dandee can compose a pretty enough string of words about his aching love and the hard rain when he’s mis-sin’ you. The Lord must know things I sure didn’t–you desi-rin’ such debasement. It seems Jasper was more inspired to write that sinful muck than read the Good Book, and you was more inclined to read it. He shoulda spent more effort learnin’ to plow straight. His furrows are as bent as his morals. He’ll be with you by mornin’.” Preacher Tindal stopped when he saw his spittle glisten and cling to the sparse white strands of Martha Love’s hair. He became aware of his twisted brow. He stepped back and calmed. “I havta get out to the barn now. Folks should be around shortly. I have written them a new sermon.” He decided there wasn’t time to change into

a new suit and sprinkled himself instead with honeysuckle oil from a small bottle kept in an inside breast pocket--close to his heart.

He crossed the hard-packed yard. He thought he could hear the busy voices of congregation– his congregation–in the barn. The moon had risen farther, a faucet pouring light into the black night. The house, the barn, and the surrounding hills had texture. He could see as clearly as in daylight. The walled ruin of the ancient asylum was defined on a ridgeline miles away to the southeast. He stood still in the glow. Only his green eyes moved in his survey of all that was. All that is. He could feel the moon’s light upon his face and hands.

Only a few are permitted Divine, weightless gifts. The congrega-tion could wait another minute. They were busy with each other anyhow. Catching up on gossip. Perhaps he should burn the barn to the ground. Save the sheep from eternal damnation. Grant them atonement through his self-less responsibility. He admired the land, the repetition of hills, the distant ruin in the blue hue. Everything is temporary. After a while, he lowered his head. He entered the barn and walked through bright strips of light toward the pulpit, smiling and nodding. He took his posi-tion atop the hay bales. He was sliced in sections by the moon-light. He lifted his face upward, and his green eyes glowed like those of a nocturnal predator. He raised his arms in a gesture

of silence, though there was no sound to be heard, and began: “To many folks, the meaning of life strips down to the happy times they get to enjoy while on this wonderful earth. I’m fixin’ to tell you it’s about more than just that.” The chickens blinked, alerted again from their slum-ber. A pig shifted his jowls and haunches deeper into the damp dirt. Others snored and farted. The cow rolled her head side-ways, and started to swing her tail. Soon they would be fully roused by the fiery speech of Preacher Tindal.

art by James Furlong

28

Joan Hofmann

Below the Surface

29

The side unseen is the show. Common enough,the black cormorant draws little attention on the waterfront.If we notice, it’s its preening or strange stancewith wonky wings awry drying symmetricallythat catch the eye. Without the waterproofing oil of other seabirds,it stands long times drying its wings in air and sun, in between acts.Or it displays its talent of dipping into water in one placeand emerging seconds later at a distance unsuspected.

An oddity as much as anything,a cormorant spends its time in the wateror around it, whether fresh or salt.I remember, sitting together, my mother saidI was beautiful on the inside and the outside. It’s funny

what you think of and hold onto. Her words stayin my pocket where I finger them for warmth.It’s what’s under that matters: underwater, a cormorantbursts a display of oily bubbles rushing into a rainbow,its buoyant self seen by the looking few—something somecan only imagine, lacking the sight of a heron who, likemy mother, sees at the waterline, above and below the surface.

art by Tamika Ocasio

art by Carol Peters

art by Danielle Sitler

art by Zuzanna Bartnik

art by Griffin

31

Richard Chotkowski

Firewood

The pale blue tarpwarmed by the sun hidesa pile of firewood stillfrozen solid at the bottom. The wood on the top is dry and warm.

Between the warm and the frozenare papery snake skins left behind, tight spider-web balls with little green babies inside waiting for the spring they will never seebecause I crush them, (not without sorrow, although I am no Buddhist), or else they’d be in the house big,furry and brown.

Wads of dried matted grass constructionfill voids like suburbs: mouse-house foreclosures. A pelt, the gray overcoat a mouse left behind, as if he took it off to iron out the wrinkles. The smells in the woodpile are a musky mixof nature alive in every nook and cranny and warped husk of bark.

Three weeks later the bottomrows are thawed and hauled inside,burned to a wispy spiral of smoke,through and out the chimney holeinto the clear blue sky.A respite for carbon.The end and the beginning.

30

32

A field of wildflowers–– as if the sun as if the sunhad dreamed

Despair––graced by thelilac bush

Dreamlessness––the cricketchirps a condolence

Heather Strickland

A Field of Wildflowers

art by Stephen Sottile

33

after Cheryl Savageau

Like my mother now passed, I wash out plastic bagsto use again. Pint-sized, sandwich, quart.Plastic containers from the deli, take-out. I rinse outglass jars of mayonnaise and jelly. I stacknewspapers for box stuffing, wood-stove starting.I fold wrapping paper, slowly removing tape.Ribbon, bows, gift bags, peanut packing.Sunlight on the wavy-glass windows, darting hummers atthe feeder, seeds from last year’s Sweet William,geranium stalks in cold storage, begonia branchesover winter. I hold onto his daring looks, her smiles of support,how I massaged my mother’s legs, propped my father’s head.I hold a blanket he used, wear her sweater still.

I plant the pansies they loved,all around me.

Joan Hofmann

Keepers

art by Joy Falcon

art by Breanna L. Palumbo

34 35photo by Christine Brozyna

Michael DiRaimo

Grading Essays for Comp Class

There they are squatting on the desktopwaiting for me to ruffle their monotonousdouble-spaced existenceto flip through a few pages to bring forth the tincture of red inkto move the better ones to the top of the packthe ones I usually read first: “priming the pump,” I call it, getting a taste of the not-so-bad before the descent into a hell of solecismincoherenceplagiarism and conclusions that repeat introductions.“Naked came I and naked I leave,”I think to myself.

They do not beckon, as do most items that grab a poet’s attentionat the start of a poem like this.They are distinctly incapableof being my museand I, theirs.

No––in factthey compel me to do other things:vacuum the hall carpetpare apples for an apple sauceto sweeten tonight’s pork loin

play with my indifferent catcheck last night’s box scores––

gestures that at some other momentand in some other poemwould bespeak my loving connection to my small world, my joy in simple deeds,but now merely expose my desire to be any place but hereto have anything to do but this.

art by Breanna L. Palumbo

3736

Your fingers squeeze the plastic knob, its tiny ridges grip the flesh.Go ahead and twist. Hard.Not that way, the other way. Until you feel it click.

The wires inside the bulb, inside the vacuum,conduct the electricityand glow like the sun, spread instant light and shadowseverywhere.

Your eyes squint at the surprise,maybe feel a pulse of pain, like a tiny hammer-tapon the nerves hidden behind them.Or maybe you anticipated and squished the lids shut,now slowly opening them, a sliver, a crack,feel the lashes disengage, like nature’s Velcro,or ocular baleen, filter-feeding on photons, the plankton in light waves,making the seamless adjustment from darknessto the world of shapes and colors.

Richard Chotkowski

Let There Be Light

photo by Joseph Kalos

art by Ryan King

art by Megan Evans

38 39art by Lucy Sander Sceery

art by Andrea Finch

John Stanizzi

So Much Trouble in the World

Bless my eyes this morningJah sun is on the rise once again ––Bob Marley

. . . but not always. Take for instance the comingdawn for which I wait here every morning,looking at the room reflected therein the glossy windowpane that’s black with night,and which will slowly reveal its transparency,and among the lighted shapes a distinct and subtlelack of trouble: the serenity of the surfaceof the pond braced for winter inits crystal severity, the reeds along the shore dead and golden, the sky a heavygray that I’ll inhale voraciously.Are we really so preoccupied with the cost of things,or when the next advantage will come our way,that we miss the tiny dashes of snow behindthe bulb that casts a suspended yellow aura on the animal prints in the snow moving away,melting into the inundation of light,toward the warmth of some tiny, quiet place?

40 41

art by Mary Ionno

photo by Megan Toth

Stephen Campiglio

Westward East The horse-drawn hearse clops through my grandmother’s dreamand stops in front of her house. The premonition soon comes true and her husband dies.Fresh with grief, she returns to the dream world,while he’s still close, to identify who his patron saint will be, and by morning knows that it’s Mary,Mary who let the horses run free.

My grandmother kept the Old World contiguous to the Newby digging and planting; her tar-locked garden flush with tomatoes, basil, squash and greens,her chicoria so good it simplified all my needs. Now, without her, simplicity is complicated;my people further removed.

art by Andres Reyes

42 43

photo by Joshua Howe

photo by Anonymous

photo by Danielle Worthington

Valerie Rizzo

Wilderness Program

I went into the wildernessOf the Idaho desert basin.I was supposed to learnHow to be a better person.But I learned nothing really,Just that I really like camping.I like the quiet desertWith all its dirt and dustSwirling over the sage bushesAnd the prickly cactiThat watch over our campsiteIlluminated with campfire flamesAnd dulled with program talk.

I like listeningTo the nothingnessBetween desert sandsAnd the sun.I like listeningTo the emptinessOf the every nightClear sky.

44 45

art by Aiwei Deng

Natasha Davis

You Bring Out the Mad Black Woman in Me

after Jim Daniels

The Bernie Harris in me. The HelenSimmons-McCarter in me. The snoopin me. The Inspector Gadget in me.The hiding in the bushes with some binoculars in me.The leather strap in me.The I’m gonna get you back in me.You bring out the bitch in me. The knife-wielding psychopathslasher in me. You bring out the Lorena Bobbitt in me.The Mike Tyson, first round knockout in me.You bring out the Tony Montanain me. The guns blazing, bullets flying across the roomin me. At the same time, you bring out the competition in me.The Usain Bolt in me.You bring out the good girlgone bad in me. The Rihanna in me.The hard in me. You bring out the I don’t carein me. You bring out the alcoholic in me.The pigeon-toed walking drunk in me.You bring out the reckless in me.The jeans hanging low, trigger finger pointed,hat to the back in me.The thug in me.You bring out the misery in me.The pour gasoline on your clothesthrow it in the backseatlight your car on fire in me.You bring out the stalker in me.The PI in me.The pop up at your house in me.Out of all the things you

bring out in me, you didn’t bring out the you in me.Thank God.

art by Emily Albee

art by Anonymous46 47photo by Hanish Rubanza

Matt Prince

The Life of a Street Musician

He plays his drums out on the street,hoping to earn something to eat.Maybe a slice of one of New York’s pies,bought with the change from passersby.His drumsticks come from nearby trees,he drums whatever he finds or sees.He clicks, and clacks, and beats away,from early morning to end of day.He plays for crowds both young and old.He once was shy, but now he’s bold.He’s earned himself a small amount of fame,and the locals all know his name.They say, “Hey Johnny, give me a beat.”He replies, “Here’s a little something to move your feet.”He’s played back-up to other musicians as they sang their song,but alas his fame has come and gone.The disease keeps him in bed and off the streets,and far too weak to play his beats.His health is fading, his body is weak.He has no energy left even to speak.The streets have been quiet for an entire week,as folks mourn the fact that Johnny’s life is complete.On the street where he used to play,lie letters with ink the rain has almost washed away,and in the evolution of life and things,where he once played now someone sings.

48 49

Steve Straight

Deleted ScenesOn the back of the DVD of the classic filmI’ve just finished watching, I see there are “deleted scenes.”Still reveling in the satisfying world of lovers lostand reunited, the caper’s plot unfolded like a lace kerchiefto reveal a pearl, I am loathe to watch them.

What will they add to my experience of that neat little universe, these moments when the characters didn’t have the perfect retort, were instead mumbling and verbose,or when subplots dribbled off into meaninglessness?

These scenes that didn’t make the cut are too much a reminder of our own lives filled with so many moments worth deleting, the inching lines of cars during all those rush hours,bed-tossing colds and flus, meetings reduced to doodling.What would I want with more imperfection?

Some DVDs would provide me with “alternate endings,”as if the lives depicted were all whim and happenstancelike ours, all those effects of choices I didn’t make,luck I had or didn’t have, causing alternate livesto fork and fork each time into what is now a giant tree,me far out on the end of a single limbthat bobs precariously in the wind.Do I need to be reminded?

In one phase of my life, I heard the stories of near-death experiencers, who described their life reviews in the presence of a being of light, and to their surprise many of them, with access to any moment in their lives,

said it wasn’t the promotion, or the A on the term paper, or even the wedding that appeared, but insteadthe tiny moments of kindness they had long forgotten,

shoveling a neighbor shut-in’s walk after the storm,taking the crying little boy’s hand to help find his mother,refusing to join in tormenting the disabled girlway back in second grade, these were magnifieda thousandfold.

Those scenes I have deleted by neglect or oversight, the moments when I rose to the level of mensch,those I would be willing to watch,the Director’s own cut.

art by Susan Whitehouse

art by Andrew Walz

50

photo by Leah Broadwell

photo by Ken Marceau

photo by Rachel Fusco

Jeanine DeRusha

Job’s Wife

There he goes again, with his dark madness,the fitful praying. His futile sobbing,the fist-shaking. She can hardly watchas he loses everything they had. Land,house, cattle, all ten children. She sharpens his bandsaw with the garnet,not to rebuild, but for him to end it.This has nothing to do with good wife orbad. The soil beneath their feet was plagued,and she knew law was nothing about fair. She begged him to end his life, to curse Godfor this injustice. She said that curseswere prayers, only tougher. He hung onthrough winter, through blowing driftsof snow, through unknown depths of cold. He refused her death threats, refused her love.She hung on, too, though nothing is eversaid of this dedication, of her strongfidelity – not to God, but to the manshe married. Finally, spring came,and the cattle raised up slow as grass blades,ten new buds formed thin spinal cords,green tendrils that reached outinto warm August air.

photo by Charlotte Panke