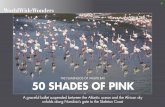

SEO Birdlife - Sociedad Española de Ornitología - Greater flamingos Phoenicopterus ... ·...

Transcript of SEO Birdlife - Sociedad Española de Ornitología - Greater flamingos Phoenicopterus ... ·...

1 23

Behavioral Ecology andSociobiology ISSN 0340-5443Volume 65Number 4 Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011)65:665-673DOI 10.1007/s00265-010-1068-z

Greater flamingos Phoenicopterus roseususe uropygial secretions as make-up

1 23

Your article is protected by copyright and

all rights are held exclusively by Springer-

Verlag. This e-offprint is for personal use only

and shall not be self-archived in electronic

repositories. If you wish to self-archive your

work, please use the accepted author’s

version for posting to your own website or

your institution’s repository. You may further

deposit the accepted author’s version on a

funder’s repository at a funder’s request,

provided it is not made publicly available until

12 months after publication.

ORIGINAL PAPER

Greater flamingos Phoenicopterus roseus use uropygialsecretions as make-up

Juan A. Amat & Miguel A. Rendón &

Juan Garrido-Fernández & Araceli Garrido &

Manuel Rendón-Martos & Antonio Pérez-Gálvez

Received: 14 July 2010 /Revised: 27 August 2010 /Accepted: 20 September 2010 /Published online: 23 October 2010# Springer-Verlag 2010

Abstract It was long thought that the colour of birdfeathers does not change after plumage moult. However,there is increasing evidence that the colour of feathers maychange due to abrasion, photochemical change and staining,either accidental or deliberate. The coloration of plumagedue to deliberate staining, i.e. with cosmetic purposes, mayhelp individuals to communicate their quality to conspe-cifics. The presence of carotenoids in preen oils has beenpreviously only suggested, and here we confirm for the firsttime its presence in such oils. Moreover, the carotenoids inthe uropygial secretions were the same specific pigmentsfound in feathers. We show not only that the colour offeathers of greater flamingos Phoenicopterus roseusbecame more colourful due to the application of carote-

noids from uropygial secretions over the plumage but alsothat the feathers became more colourful with the quantityof pigments applied over them, thus providing evidence ofcosmetic coloration. Flamingos used uropygial secretionsas cosmetic much more frequently during periods whenthey were displaying in groups than during the rest of theyear, suggesting that the primary function of cosmeticcoloration is mate choice. Individuals with more colourfulplumage initiated nesting earlier. There was a correlationbetween plumage coloration before and after removal ofuropygial secretions from feathers’ surfaces, suggestingthat the use of these pigmented secretions may function asa signal amplifier by increasing the perceptibility ofplumage colour, and hence of individual quality. As thecosmetic coloration strengthens signal intensity by rein-forcing base-plumage colour, its use may help to theunderstanding of selection for signal efficacy by makinginterindividual differences more apparent.

Keywords Carotenoids . Cosmetic coloration . Plumagecolour . Plumage maintenance . Signals . Uropygialsecretions

Introduction

Carotenoids are the basis of some plumage colours, such asred, yellow and orange (Hill 2002). These pigments areincorporated into feathers during moult, and as they cannotbe synthesised by animals, but have to be ingested withfood, plumage colour may be used to communicate theability to obtain resources (Hill 2002; Searcy and Nowicki2005). Plumage colour has been traditionally considered asa static trait, with little opportunity for individuals to altertheir appearance if conditions change between moulting

Communicated by J. Lindström

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article(doi:10.1007/s00265-010-1068-z) contains supplementary material,which is available to authorized users.

J. A. Amat (*) :M. A. RendónDepartment of Wetland Ecology, Estación Biológica de Doñana,Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas,Calle Américo Vespucio s/n,41092 Sevilla, Spaine-mail: [email protected]

J. Garrido-Fernández :A. Pérez-GálvezFood Biotechnology Department, Instituto de la Grasa,Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas,Avenida Padre García Tejero 4,41012 Sevilla, Spain

A. Garrido :M. Rendón-MartosReserva Natural Laguna de Fuente de Piedra,Consejería de Medio Ambiente, Junta de Andalucía,Apartado 1,29520 Fuente de Piedra, Spain

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673DOI 10.1007/s00265-010-1068-z

Author's personal copy

periods. However, there is increasing evidence that thecolour of feathers may change due to abrasion, photochem-ical change and staining, either accidental or deliberate(Uchida 1970; Negro et al. 1999; Piersma et al. 1999;McGraw and Hill 2004; Blanco et al. 2005; Figuerola andSenar 2005; Montgomerie 2006; Delhey et al. 2007;Surmacki 2008). Indeed, some bird species are known tomodify the colour of their feathers or other body parts bymeans of the deliberate application of substances, whichmay be either external to the birds (Negro et al. 1999;Montgomerie 2006; Delhey et al. 2007; Surmacki andNowakowski 2007) or produced by the birds themselves(Uchida 1970; Montgomerie 2006; Delhey et al. 2007;Surmacki and Nowakowski 2007; Piault et al. 2008; López-Rull et al. 2010). Among the substances produced by thebirds are the secretions of the uropygial gland, which maybe pigmented orange, red or yellow (Stegmann 1956;Vevers 1985). It has been suggested that carotenoidpigments are present in preen oils, and that these pigmentstinge the plumage when artificially transferred onto it(Stegmann 1956). It has also been suggested that thesecretions of the uropygial gland may act as cosmetics bymodifying the spectral shape of the reflected light (Delheyet al. 2007). However, to our knowledge, neither thepresence of carotenoids in the uropygial secretions, neithertheir potential role as cosmetics because of the changes thatthey may produce in feather coloration, have beendemonstrated.

The use of cosmetics has been reported in somevertebrate taxa, such as fishes, birds and mammals, andhas received little attention by behavioural ecologists(Delhey et al. 2007). Although it has been suggested thatthis type of coloration has a signalling function, byproviding a reinforcing mechanism linking body colorationand fitness-related traits (Negro et al. 1999; Piersma et al.1999), the mechanisms by which this is achieved have notbeen addressed. To act as an honest signal, the cosmeticcoloration should have some cost (Zahavi 1975; Grafen1990). In the case of birds, time and energy costs may beassociated with the maintenance of plumage coloration(Delhey et al. 2007; Griggio et al. 2010). First, if thecosmetics are carotenoids, frequent reapplication would berequired to maintain plumage coloration since these pig-ments bleach rather quickly when exposed to ambientconditions, thus causing the fading of colours (Vevers 1985;Delhey et al. 2007). Second, to apply the cosmetics onfeathers, birds may use specific, time-demanding behaviour(Delhey et al. 2007; Griggio et al. 2010) so that timedevoted to other activities may be limited. In addition, theremay also be physiological costs since carotenoids are usedin some biological functions, and because they arepotentially a limiting resource, trade-offs among suchfunctions are likely (see Discussion).

In most cases, the proposed signalling function ofcosmetic coloration has been sexual, as this type ofcoloration mainly develops during breeding or displaying(Delhey et al. 2007). Accordingly, we predicted that (1) theuse of cosmetic coloration should be more prevalent whenindividuals are acquiring mates than during other parts ofthe year, and that if the pigments used for cosmeticcoloration act as a reinforcing mechanism of honestsignalling, (2) the pigments found in the uropygialsecretions should be the same as those found insidefeathers, and then (3) there should be a correlation betweenthe use of cosmetic coloration and base-plumage colour(i.e. the quantity of pigments on feathers’ surfaces shouldbe related to feather colour once external pigments areremoved). Finally, if the cosmetic coloration functions asa kind of honest signal, there should be a correlationbetween its use and some measure of individual quality.

The reliability of honest signals is ensured because they arecostly to produce (Zahavi 1975; Grafen 1990). But signalsshould not only communicate reliably the quality ofindividuals—they also need to be efficient in reaching targetdestination and elicit a response (Guilford and Dawkins1991; Maynard Smith and Harper 2003). Because plumagecolour changes at moult, several months before mate choice,the information conveyed by colour may be out of date whenindividuals make assessments (Searcy and Nowicki 2005;Montgomerie 2006). Under these circumstances, the abilityof individuals to physically manipulate the perception oftheir own signals may make the signals (i.e. plumage colour)more easily to be perceived at times when such signals mustbe functional. In this context, our findings may haveimportant implications to the understanding of selection forsignal efficacy, as the cosmetic coloration may reinforcebase-plumage coloration, and thus may make interindividualdifferences more apparent, which is consistent with the ideathat redundancy increases efficacy (Maynard Smith andHarper 2003).

Study species

We tested the above predictions using the greater flamingoPhoenicopterus roseus as a model. This species is ideal tolook for evidence of cosmetic coloration, as the adultplumage exhibits temporal variation in colour that does notseem to be related to moult (Cramp and Simmons 1977;Shannon 2000). Furthermore, carotenoids (mainly cantha-xanthin) are responsible for their pink colour (Fox 1975).Greater flamingos are monogamous and both males andfemales participate in incubation and chick rearing (Johnsonand Cézilly 2007). The rate of mate splitting betweenconsecutive breeding seasons is very high (98%, Cézillyand Johnson 1995). Flamingos display in mixed groups ofmales and females several months before breeding (Cramp

666 Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673

Author's personal copy

and Simmons 1977), suggesting that assessment of potentialmates is very important. Plumage colour may play a functionduring such assessment, as during the displays the birdsexhibit the most coloured plumage patches (Cramp andSimmons 1977). Hence, we first studied seasonal variationsin plumage colour in relation to courtship activity. Next, welooked for the pigments that may tinge the plumage both inthe secretions of the uropygial gland and on feathers’surface, i.e. external to the plumage. We then studiedwhether there was specific maintenance behaviour ofplumage related to the cosmetic acquisition of coloration.Finally, we asked whether the cosmetic coloration ofplumage was correlated with a reliable predictor of annualreproductive success: date of egg-laying.

Materials and methods

Allocation of colour to neck plumage

To record seasonal variations in plumage colour of greaterflamingos, we visited three wetlands in southern Spain(Guadalquivir marshes—36°55′63″ N, 6°15′89″ W; Odielmarshes—37°15′56″N, 6°59′29″W; Fuente de Piedra lake—37°06′86″ N, 4°46′17″ W), during 2004–2006, and recordedthe colour of neck feathers of adult birds by scanning flocksusing a spotting scope. The two marshes are the main feedingareas during the chick provisioning period of greaterflamingos breeding at Fuente de Piedra (Amat et al. 2005).We allocated the colour to three scores: (1) very pale pinkthat at distance looks white, (2) pale pink and (3) pink (seeElectronic supplementary material). We performed theobservations to allocate plumage colours in the morning(06:00–11:00 h, GMT). Although we used a coarse colour-scoring method, human vision may provide a valid proxy foravian perception of interindividual differences in plum-age coloration (Hill et al. 1999; Seddon et al. 2010).There was a close agreement among three observers (JAA,AG, MAR) in the assignment of neck colour scores to 50individual flamingos (Kendall coefficient of concordance,W=0.89, P<0.001).

Laying dates

To relate neck plumage colour scores to laying dates, weconducted observations at the Fuente de Piedra breedingcolony during 42 days in 2004, from late February until lateJune. The observations were conducted during the morning(06:00–11:00 h, GMT) on individually marked birds withPVC rings that could be read from a distance of up to300 m using a telescope. We recorded the date and neckcolour the first time that individually marked birds wereobserved in the breeding island. We used the date of first

sighting in the breeding colony as a surrogate of layingdate because there was a significant relationship betweenthe date of first observation and actual laying date(Spearman’s rank correlation, rs=0.72, n=34, P<0.001),and this allowed us to increase sample size. To checkwhether the colour fades just after the flamingos start tobreed, i.e. when individuals stop participating in groupdisplays, neck colour was recorded once more when theindividuals were observed again in the colony at least21 days later (mean±SD=51.6±22.9 days, n=193) afterthey were observed the first time. As incubation lastsabout 30 days (Cramp and Simmons 1977; Johnson andCézilly 2007), the second time that we recorded theindividuals they were usually attending chicks.

It is well known that in many bird species laying dateadvances with the age of the female (e.g. Perdeck and Cavé1992). Because of this, age may be a confounding factor inthe relationship between plumage coloration and layingdate so that we controlled for age effect (see below). Age inrelation to date of first observation in the colony wasknown for 219 greater flamingos that were marked aschicks with PVC rings with individual codes.

Maintenance behaviour of plumage

We recorded the maintenance behaviour of plumage byflamingos during periods in which group displays wereobserved, which in southern Spain usually takes placebetween October and April, and periods in which no suchdisplays were observed (May–September). During groupdisplays, the plumage is ruffled, the necks are stretchedupwards and the heads are jerked from side to side in fixedrhythm, and a function of group displays may be matechoice (Cramp and Simmons 1977; Johnson and Cézilly2007). We distinguished between two types of maintenancebehaviour: ‘rubbing’ (defined also as ‘daubing’ [Uchida1970]), in which the head is thrown back, the crown restson the upper back and is then rotated from side to side (seePlate 1c in Kahl 1972), usually after rubbing their cheeksdirectly on their uropygial glands; and ‘preening’, in whichthe individual uses lateral strokes of its bill to preen theupper breast and lower neck feathers (see Plate 1a in Kahl1972). While the aim of ‘rubbing’ is cosmetic (see below),that of preening is mainly directed to rearrangement offeathers and removal of ectoparasites. To record themaintenance behaviour, we scan-sampled (Altmann 1974)flocks of flamingos at Odiel and Guadalquivir marshes, aswell as at Fuente de Piedra lake, between 06:00 and 11:00 h(GMT), during both the displaying period (October–April)and outside that period (May–September). We recorded themaintenance behaviour of a mean number of 108.6±(SD)56.4 individuals during each recording day (n=23),allocating the behaviour to either rubbing or preening, and

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673 667

Author's personal copy

assigning neck colour scores to those individuals. Althoughnot all birds were marked, the probability of resampling thesame individuals was small. Out of 333 observations onindividually marked birds, we resampled 19 individualstwice (38 observations, 11.4%), and three individuals wereresampled three times (2.7%). However, in all these cases,resampling was done in different months, or even years. Forsuch reasons, the observations on the same individuals maybe considered as independent.

Pigments in the uropygial secretions and on neck feathers

We obtained samples of uropygial secretions fromcaptive greater flamingos by softly massaging the nippleof the preen gland (Reneerkens et al. 2002), in October(19 individuals), February (15 individuals) and July (12individuals), with the aim of studying seasonal variationsin the concentration of carotenoids in the uropygialsecretions. We sampled 35 individuals, of which sevenwere sampled twice and two were sampled three times.The captive birds came from the same population wherebehavioural data were recorded. We collected up to 50 mgof uropygial secretions per sample using micropipettes andtransferred the samples into 2-mL Eppendorf round-capped tubes for subsequent extraction of pigments. Thesamples were kept at 4°C until transportation to alaboratory, within the next 5 h after collection, where theywere frozen at −20°C until analyses within the next week.Before freezing, we recorded to the nearest 0.1 mg themass of secretions of every sample using a Mettler Toledoelectronic balance. For carotenoid extraction, we added60–150 μL of acetone (the quantity varied depending onthe intensity of the apparent colour) to each sample ofuropygial secretions. This was shaken for 2 min, andsubsequently it was subject to sonication for 2 min. Thesample was then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 5 min and theupper layer stored at −30°C until analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

HPLC analyses were carried out using a Waters 600Eseparation module and a Waters 996 PDA detector,controlled by the Empower Pro software. Separation wasperformed on a Kromasil C18 column (250×4.6 mm ID,particle size 5 μm) by using the chromatographic method(Mínguez-Mosquera and Hornero-Méndez 1993), whichconsists of a binary solvent gradient acetone–water at aflow rate of 1.5 mL min−1. The diode array detectorwavelength was set at 450 nm and the UV–visible spectraof each peak were recorded and stored online in the 350–600-nm wavelength range. Identification of carotenoidspresent in the uropygial secretions, as well as on feathers’surface (see below), was performed by separation andisolation of the pigments by thin layer chromatographic andcochromatography with standards, acquisition of UV–

visible spectra in different solvents, as well as chemicalderivatisation microscale tests for the examination offunctional groups (Eugster 1995). The different properties(chromatographic, spectroscopic and chemical) of the pig-ments were compared with standards and data in theliterature (Foppen 1971; Davies and Köst 1988; Britton1995). Quantification was performed using external stan-dard calibration curves from injection of progressiveconcentrations of the reference pigment.

To determine whether pigments in the uropygial secre-tions were transferred onto the plumage, we collected neckfeathers, as well as uropygial secretions as indicated above,from 16 captive individuals. Carotenoid concentrations inthe uropygial secretions of these 16 birds were determinedas indicated above. The feathers were introduced in 15-mLFalcon tubes filled with acetone for pigment extraction. Inthe laboratory, these tubes were shaken during 2 min, usingVortex, after which they were subject to sonication during2 min. Pigment extracts were transferred to a rotatory flaskand the solvent was evaporated until it was dry. The residuewas dissolved in 100–300 μL of N,N-dimethylformamide(the quantity varied depending on the intensity of theapparent colour), filtered through a nylon net (0.45-μmmesh size) into an Eppendorf tube and stored at −30°C untilanalysis. In a pilot study, we did not obtain any pigmentfrom feathers from which external uropygial secretions hadbeen previously removed, indicating that our method wasadequate. That is, with our procedure we did not removeany pigment internal to feathers.

Effect of pigment removal on feathers’ colour

The effect of pigment removal on colour was studied bycomparing feather colour before and after removal ofexternal pigments. To measure colour, we scanned neckfeathers <4 h after collection and again after removal ofexternal pigments. We used an Epson Perfection 1250scanner, with a resolution of 1,200 pixels. Scanned imagesof neck feathers were imported at maximal resolution andsaved as JPEG files, from which hue, saturation andbrightness were recorded using Photoshop Elements(Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA). The eyedropper was setat 5×5 pixels and placed over five points along thefeather images (see Electronic supplementary material)where hue, saturation and brightness were measured andthen averaged for each feather. Hue defines the colouritself, for example, red in distinction to blue or yellow. Thevalues for the hue axis are expressed in degrees and runfrom 0 to 360°, beginning and ending with red andrunning through green, blue and all intermediary colours;in the particular case of flamingo feathers, increasing huevalues refers to less red (paler) colours. Saturationindicates the degree to which the hue differs from a

668 Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673

Author's personal copy

neutral grey; the values run from 0%, which is no coloursaturation, to 100%, which is the fullest saturation of agiven hue at a given percentage of illumination. Bright-ness indicates the level of illumination. The values run aspercentages; 0% appears black (no light) while 100% isfull illumination, which washes out the colour (it appearswhite).

We quantified colour as it is perceived by the humaneye. Birds, however, are also sensitive to ultraviolet (UV)light (Bennett and Cuthill 1994), and if uropygial secretionsaffect UV reflectance, this may have important effects onplumage colour as perceived by birds. However, theuropygial secretions are unlikely to play a major role inmodifying plumage UV reflectance (Delhey et al. 2008; butsee Griggio et al. 2010).

Statistical analyses

We used Wilcoxon matched pairs test to compare plumagecolour scores before and after chick hatching as well asfeathers’ colour before and after pigment removal. Spear-man rank correlations were used to examine the relation-ship between plumage colour and the concentration ofpigments on feathers’ surfaces, as well as the relationshipbetween feathers’ colour before and after pigment removal,and the relationship between birds’ age and laying dates.We used Kendall partial-rank correlations to control forbase-plumage colour on the relationship between plumagecolour and the concentration of carotenoids on feathers’surfaces, and also to control for the effect of birds’ age on therelationship between plumage coloration and laying dates.Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was used to analyse monthlyvariations in plumage colour scores, seasonal variations inthe concentrations of pigments in the uropygial secretions anddifferences in laying dates according to plumage colourscores. Finally, we used χ2 tests to analyse differences inmaintenance behaviour of plumage between displaying andnon-displaying periods as well as in maintenance behaviouraccording to neck plumage colour scores. Analyses wereperformed using STATISTICA (StatSoft 2001). The signif-icance level was alpha <0.05.

Results

Seasonal variations in plumage colour

Observations in southern Spain indicated that theplumage of free-ranging flamingos was more colourfulduring periods in which the birds were displaying ingroups (October–April) and faded during the rest of theyear (Fig. 1; Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA—H11=502.6, n=1,814, P<0.001). The fading in plumage colour mainly

occurred just after the birds started to breed. Indeed, at thetime of laying, mean neck plumage colour scores ofindividual birds were higher (1.82±SD 0.68) than oncetheir chicks had hatched (1.61±0.66; Wilcoxon matchedpairs test—z=3.30, n=193, P=0.001). These variations inplumage colour did not seem to be related to moult sinceadults with chicks typically start feather replacement afterchick emancipation (Cramp and Simmons 1977; Shannon2000).

Pigments in uropygial secretions and feathers

We observed on several occasions wild greater flamingosrubbing their cheeks directly on their uropygial glands,which suggested that the birds could use the secretions ofthis gland to tinge their plumages. Indeed, we foundcarotenoids in the uropygial secretions of all except onebird, at a mean concentration of 0.59±(SD) 0.63 mg ofcanthaxanthin per kilogram of uropygial secretions (n=62).As in the case of feathers (Fox 1975), canthaxanthin wasthe main pigment found in the secretions (see Electronicsupplementary material), although β-cryptoxanthin wasalso found in a few birds in very small quantities. Totransfer the pigments from the uropygial gland onto theplumage with cosmetic purposes, the flamingos rubbed thehead on neck, breast and anterior back feathers. Thisrubbing behaviour was much more frequent during thedisplaying period than during the rest of the year (Fig. 2;χ1

2=333.1, P<0.001). In addition, rubbing was performedmuch more frequently by birds with the highest plumagecolour scores, i.e. the most colourful birds, than by palerbirds (Fig. 2; χ2

2=547.9, P<0.001).

JanFeb

MarApr

MayJun

JulAug

SepOct

NovDec

Month

0,8

1,0

1,2

1,4

1,6

1,8

2,0

Nec

k co

lou

r sc

ore

Fig. 1 Monthly variations of mean neck plumage colour scores ofadult greater flamingos in wetlands of southern Spain. Plumage colourwas allocated to three categories: (1) very pale pink that at distancelooks white, (2) pale pink and (3) pink (see Electronic supplementarymaterial). Sample sizes varied 18–405. Error bars indicate 95%confidence intervals

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673 669

Author's personal copy

Canthaxanthin was also found on feathers’ surface, i.e.external to plumage, in all 16 individuals examined, at a meanconcentration of 57.1±34.72 μg of canthaxanthin per kilo-gram of feathers. The colour of neck feathers faded afterremoval of external pigments as hue increased [36.5±7.81(pigments removed) vs. 32.7±6.82 (pigments not removed);Wilcoxon matched pairs test—z=2.13, n=16, P=0.033] andsaturation decreased (4.7±1.95 vs. 7.1±2.60; z=3.35, P<0.001). However, there were no differences in plumagebrightness (95.6±0.82 vs. 95.3±1.33; z=1.16, P=0.245).There was a significant relationship between feathers’ huebefore pigment removal and the concentration of canthaxan-thin on feathers’ surfaces (Fig. 3; rs=−0.51, n=16, P=0.046). However, feathers’ hues before and after externalpigment removal were also related (rs=0.69, n=16, P=0.003). After controlling for base-plumage colour (i.e. forfeathers’ hue after external pigment removal), the relation-ship between the feathers’ hue before pigment removal andthe concentration of carotenoids on feather surfaces (i.e.external to plumage) remained (Kendall partial rank corre-lation coefficient, T=−0.49, n=16, P<0.005). This indicatesthat the plumage becomes more colourful with the quantityof pigments applied onto it.

Because the feathers became more colourful when thequantity of pigments applied over them was greater, andplumage colour varied seasonally, we asked whetherseasonal variations in neck plumage colour were paralleledby seasonal variations in the concentrations of pigments inthe uropygial secretions. We found that pigment concen-trations were higher during autumn and winter, when the

birds were more colourful (Fig. 1), than during summer(Fig. 4; Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA—H2=17.67, n=46,P=0.001).

Plumage coloration and laying dates

The fact that the plumage coloration faded after breedingonset may indicate that the maintenance of plumage colourby cosmetic coloration is costly and could be used insignalling. So, we also asked whether the cosmeticcoloration of plumage was correlated with a reliable

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160

Carotenoids (µg of canthaxanthin x kg-1 of feathers)

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Nec

k h

ue

(o)

Fig. 3 Relationship between the concentration of carotenoids (can-thaxanthin) on neck feathers’ surfaces and plumage hue in 16 greaterflamingos. Plumages with lower hue values are more colourful

Neck colour

Nu

mb

er o

f o

bse

rvat

ion

s

Rub

bing

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

Displaying

Pre

enin

g

1 2 30

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

Non displaying1 2 3

Fig. 2 Maintenance behaviourof plumage by greater flamingosduring displaying (October–April) and non-displaying(May–September) periodsaccording to neck plumage col-our scores, which were allocatedto three categories: (1) verypale pink that at distance lookswhite, (2) pale pink and (3)pink (see Electronicsupplementary material)

670 Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673

Author's personal copy

predictor of annual reproductive success (date of egg-laying; see Rendón et al. 2001). Individuals with morecolourful neck plumage initiated nesting earlier (Fig. 5;Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA—H2=240, n=240, P=0.0002).Nevertheless, laying dates, considered as the date of firstsighting in the breeding colony, were correlated with theage of individual flamingos (rs=−0.38, n=219, P<0.001).When the effect of age was set constant, the relationshipbetween plumage coloration and laying date remained(Kendall partial rank correlation coefficient, T=−0.15, n=219, P<0.01).

Discussion

There are very few previous studies on the effects ofuropygial secretions on plumage coloration, and the resultsare contradictory. While some studies found that preenwaxes have no effect on coloration (Reneerkens andKorsten 2004; Delhey et al. 2008; Surmacki 2008), anotherstudy found that after application of preen waxes theplumage was more colourful (López-Rull et al. 2010).These differences among studies may lie in variations of theoptical properties of uropygial secretions across species.Here, we have shown for the first time that the pigments inthe uropygial secretions are the same found in feathers, andthat greater flamingos may use these pigments withcosmetic purposes.

It has been suggested that the cosmetic behaviour couldhave a non-signalling origin, being a side effect of usingcoloured substances for feather maintenance and withoutsignalling value (Delhey et al. 2007). Here we have shownthat the colour of plumage changes with the application ofcarotenoid-rich secretions over it by the birds themselves,that the intensity of coloration increases with the quantity ofpigments applied onto the plumage, that the concentrationof carotenoids in the uropygial secretions changes season-ally in accordance with plumage colour, that for theapplication of such carotenoids the birds use specificbehaviour and that the more colourful birds start breedingearlier. All this is consistent with the notion that pigmentsin the uropygial secretions are used as cosmetic, and thatthis has a signalling function.

As suggested by López-Rull et al. (2010), cosmeticcolours may play an important role in courtship and matechoice, and would update the signal value of plumagecolour, mainly by providing a more recent snapshot of thebearer’s quality than colours acquired by moult somemonths before (Montgomerie 2006). We found a strongcorrelation between plumage coloration before and afterremoval of uropygial secretions from feathers’ surfaces.This may indicate that those secretions would add relativelylittle variation to base colour, i.e. to the colour produced bycarotenoids deposited into feathers, and therefore that theuse of cosmetic coloration would not have a signallingvalue. Nevertheless, after the application of uropygialsecretions the plumage of greater flamingos was morecolourful so that the use of these secretions may function asa signal amplifier by making the signal more detectable byconspecifics (Hasson 1991; López-Rull et al. 2010), and inturn increasing the perceptibility of individual quality.

That the primary function of cosmetic coloration inflamingos may be related to mate choice is supported by thefact that rubbing behaviour was much more frequent duringperiods when the birds were displaying in groups thanoutside those periods, and the colour of feathers due to

1 2 3

Neck colour score

28-Feb

4-Mar

9-Mar

14-Mar

19-Mar

24-Mar

29-Mar

3-Apr

8-Apr

Lay

ing

dat

e

84

122

34

Fig. 5 Mean laying dates of greater flamingos according to neckplumage colour scores. Plumage colour was allocated to threecategories: (1) very pale pink that at distance looks white, (2) palepink (3) and pink (see Electronic supplementary material). Error barsindicate 95% confidence intervals. Sample sizes are beside points

October February July

Month

0,0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1,0C

aro

ten

oid

s (m

g o

f ca

nth

axan

thin

xkg

-1 o

f se

cret

ion

s)

19

15

12

Fig. 4 Temporal variations in the mean concentration of carotenoidsin the uropygial secretions of captive adult greater flamingos. Samplesizes are beside points, and error bars indicate 95% confidenceintervals

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673 671

Author's personal copy

cosmetic coloration faded after egg hatching, likely becausethe concentration of carotenoids in the uropygial secretionswas lower than during displaying periods. In other water-birds with carotenoid-based plumage colour, it has alsobeen found that plumage colour fades just after the birdsstart to breed (Shannon 2000; Hays et al. 2006). In the caseof flamingos, there may be three reasons for this. First, itmay be that breeding birds face a trade-off between usingcarotenoids for cosmetic purposes or in ‘fighting’ freeradicals produced by oxidative stress (see Wiki 1991 andMøller et al. 2000 for physiological functions of carote-noids) during frequent commuting between breeding anddistant foraging sites during chick provisioning (Amat et al.2005). Second, and especially for females just beforelaying, carotenoids may be re-allocated from uropygialsecretions to yolk, as the latter is rich in carotenoids (Fox1975). And third, carotenoids may be re-allocated tochicks’ food, as adults feed their chicks with a secretioncontaining carotenoids (Fox 1975).

The flamingos with more coloured plumages startedlaying earlier, which may have a survival value for theiroffspring because the first pairs gained control to the bestbreeding sites (Rendón et al. 2001). This suggests that asecondary function of cosmetic coloration is to signal statusduring competition for nesting sites. In addition, the factthat rubbing behaviour is also recorded outside thedisplaying period, though to a much lesser extent thanduring the displaying period, may indicate that thissecondary function of cosmetic coloration to signal indi-vidual status may also operate at foraging areas to gainaccess to the best sites.

In addition to production costs, honest signalling mayalso have maintenance costs. Because the carotenoidsbleach rather quickly when exposed to ambient conditions,frequent reapplication of uropygial secretions rich in thesepigments should be necessary to keep the plumage colour-ful (Delhey et al. 2007). Therefore, the more colourfulindividuals should invest more in plumage maintenancethan the less colourful ones, and as time spent onmaintenance cannot be devoted to other activities, the useof cosmetic coloration may be considered as a high-maintenance handicap leading to honest signalling (Walterand Clayton 2005; Griggio et al. 2010). Indeed, we foundthat rubbing behaviour, which is related to the spreading ofuropygial secretions over the plumage with cosmeticpurposes, was much more frequently performed by themore colourful birds than by the paler ones.

Given that cosmetic coloration may be related toindividual quality, our findings may have importantimplications for the theories of sexual selection andsignalling, highlighting the key role of the manipulationof plumage colour by the birds themselves to improvesignal efficacy, as in flamingos. It remains to be determined

whether a similar mechanism is at work in other birdspecies with carotenoid-based plumage coloration.

Acknowledgements We thank M. Adrián, O. González, P. Rodríguez,N. Varo and M. Vázquez for helping to capture flamingos and takingsamples, and F. Cézilly, K. Delhey, K.J. McGraw, J.J. Negro, J.C. Senarand two referees for commenting on the manuscript. The Consejería deMedio Ambiente of the Junta de Andalucía and ‘Cañada de los Pájaros’provided facilities. Funding was provided by Ministerio de Educación yCiencia of Spain with EU–ERDF support (research grants BOS2002-04695 and CGL2005-01136/BOS).

References

Altmann J (1974) Observational study of behaviour: samplingmethods. Behaviour 49:227–267

Amat JA, Rendón MA, Rendón-Martos M, Garrido A, Ramírez JM(2005) Ranging behaviour of greater flamingos during thebreeding and post-breeding periods: linking connectivity tobiological processes. Biol Conserv 125:183–192

Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC (1994) Ultraviolet vision in birds: what is itsfunction? Vis Res 34:1471–1478

Blanco G, Frías O, Garrido-Fernández J, Hornero-Méndez D (2005)Environmental-induced acquisition of nuptial plumage expres-sion: a role of denaturation of feathers caroproteins? Proc R SocB 272:1893–1900

Britton G (1995) UV/visible spectroscopy. In: Britton G, Liaan-JensenS, Pfander H (eds) Carotenoids: spectroscopy, vol 1B. Birkäuser,Basel, pp 13–63

Cézilly F, Johnson AR (1995) Re-mating between and within breedingseasons in the greater flamingo Phoenicopterus ruber roseus. Ibis137:543–546

Cramp S, Simmons KEL (1977) The birds of the Western Palearctic,vol 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Davies BH, Köst HP (1988) Carotenoids. In: Köst HP (ed) Handbookof chromatography, vol 1. CRC, Boca Raton, pp 3–188

Delhey K, Peters A, Kempenaers B (2007) Cosmetic coloration inbirds: occurrence, function, and evolution. Am Nat 169:S145–S158

Delhey K, Peters A, Biedermann P, Kempenaers K (2008) Opticalproperties of the uropygial gland secretion: no evidence for UVcosmetics in birds. Naturwissenchaften 95:939–946

Eugster CH (1995) Chemical derivatization: microscale tests for thepresence of common functional groups in carotenoids. In: BrittonG, Liaan-Jensen S, Pfander H (eds) Carotenoids: isolation andanalysis, vol. 1A. Birkäuser, Basel, pp 71–80

Figuerola J, Senar JC (2005) Seasonal changes in carotenoid- andmelanin-based plumage coloration in the great tit Parus major.Ibis 147:797–802

Foppen FH (1971) Tables for identification of carotenoid pigments.Chromatogr Rev 14:133–298

Fox DL (1975) Carotenoids in pigmentation. In: Kear J, Duplaix-HallN (eds) Flamingos. Poyser, Berkhamsted, pp 162–182

Grafen A (1990) Sexual selection unhandicapped by the Fisherprocess. J Theor Biol 144:473–516

Griggio M, Hoi H, Pilastro A (2010) Plumage maintenance affectsultraviolet colour and female preference in the budgerigar. BehavProc 84:739–744

Guilford T, Dawkins MS (1991) Receiver psychology and theevolution of animal signals. Anim Behav 42:1–14

Hasson O (1991) Sexual displays as amplifiers: practical exampleswith an emphasis on feather decorations. Behav Ecol 2:189–197

672 Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673

Author's personal copy

Hays H, Hudon J, Cormons G, Diconstanzo J, Lima P (2006) Thepink feather blush of the roseate tern. Waterbirds 29:296–301

Hill GE (2002) A red bird in a brown bag: the function and evolutionof ornamental plumage coloration in the house finch. OxfordUniversity Press, Oxford

Hill GE, Nolan PM, Stoehr AM (1999) Pairing success relative tomale plumage redness and pigment symmetry in the house finch:temporal and geographic constancy. Behav Ecol 10:48–53

Johnson A, Cézilly F (2007) The greater flamingo. Poyser, LondonKahl MP (1972) Comparative ethology of the Ciconiidae. The wood-

storks (genera Mycteria and Ibis). Ibis 114:15–29López-Rull I, Pagán I, Macías García C (2010) Cosmetic enhancement

of signal coloration: experimental evidence in the house finch.Behav Ecol 21:781–787

Maynard Smith J, Harper D (2003) Animal signals. Oxford UniversityPress, Oxford

McGrawKJ, Hill GE (2004) Plumage color as a dynamic trait: carotenoidpigmentation of male house finches (Carpocadacus mexicanus)fades during the breeding season. Can J Zool 82:734–738

Mínguez-Mosquera MI, Hornero-Méndez D (1993) Separation andquantification of the carotenoid pigments in red peppers(Capsicum annuum L), paprika and oleoresin by reversed-phaseHPLC. J Agric Food Chem 41:1616–1620

Møller AP, Biard C, Blount JD, Houston DC, Ninni P, Saino N, SuraiPF (2000) Carotenoid-dependent signals: indicators of foragingefficiency, immunocompetence or detoxification ability? AvianPoult Biol Rev 11:137–159

Montgomerie R (2006) Cosmetic and adventitious colors. In: Hill GE,McGraw KJ (eds) Bird coloration, vol. I. Harvard UniversityPress, Cambridge, pp 399–427

Negro JJ, Margalida A, Hiraldo F, Heredia R (1999) The function ofthe cosmetic coloration of bearded vultures: when art imitateslife. Anim Behav 58:F14–F17

Perdeck AC, Cavé AJ (1992) Laying date in the coot: effects of ageand mate choice. J Anim Ecol 61:13–19

Piault R, Gasparini J, Bize P, Paulet M, McGraw KJ, Roulin A (2008)Experimental support for the make-up hypothesis in nestlingtawny owls (Strix aluco). Behav Ecol 19:703–709

Piersma T, Dekker M, Damsté JSS (1999) An avian equivalent ofmake-up? Ecol Lett 2:201–203

Rendón MA, Garrido A, Ramírez JM, Rendón-Martos M, Amat JA(2001) Despotic establishment of breeding colonies of greaterflamingos, Phoenicopterus ruber, in southern Spain. Behav EcolSociobiol 50:55–60

Reneerkens J, Korsten P (2004) Plumage reflectance is not affected bypreen wax composition in red knots Calidris canutus. J AvianBiol 35:405–409

Reneerkens J, Piersma T, Damsté JSS (2002) Sandpipers (Scolopaci-dae) switch from monoester to diester preen waxes duringcourtship and incubation, but why? Proc R Soc Lond B269:2135–2139

Searcy WA, Nowicki S (2005) The evolution of animal communica-tion: reliability and deception in signaling systems. PrincetonUniversity Press, Princeton

Seddon N, Tobias JA, Eaton M, Ödeen A (2010) Human vision canprovide a valid proxy for avian perception of sexual dichroma-tism. Auk 127:283–292

Shannon PW (2000) Plumages and molt patterns in captive Caribbeanflamingos. Waterbirds 23(Spec Publ 1):160–172

StatSoft Inc (2001) STATISTICA (data analysis software system),version 6. StatSoft, Tulsa

Stegmann B (1956) Über die Herkunft des flüchtigen rosenrotenFederpigments. J Ornithol 97:204–205

Surmacki A (2008) Preen waxes do not protect carotenoid plumagefrom bleaching by sunlight. Ibis 150:335–341

Surmacki A, Nowakowski JK (2007) Soil and preen waxes influencethe expression of carotenoid-based plumage coloration. Natur-wissenschaften 94:829–835

Uchida Y (1970) On the color change in Japanese crested ibis. A newtype of cosmetic coloration in birds. Misc Rep Yamashina InstOrnithol 6:54–72, In Japanese, with English summary

Vevers HG (1985) Colour. In: Campbell BC, Lack E (eds) Adictionary of birds. Poyser, Berkhamsted, pp 99–100

Walter BA, Clayton DH (2005) Elaborate ornaments are costly tomaintain: evidence for high maintenance handicaps. Behav Ecol16:89–95

Wiki W (1991) Biological functions and activities of animalcarotenoids. Pure Appl Chem 63:141–146

Zahavi A (1975) Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. J TheorBiol 53:205–214

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2011) 65:665–673 673

Author's personal copy

SUPPLEMENTARY ONLINE MATERIAL TO

Greater flamingos Phoenicopterus roseus use uropygial

secretions as make-up

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology

Juan A. Amat • Miguel A. Rendón • Juan Garrido-Fernández • Araceli

Garrido • Manuel Rendón-Martos • Antonio Pérez-Gálvez

_______________________________________

J. A. Amat ( ) • M. A. Rendón

Department of Wetland Ecology, Estación Biológica de Doñana, C. S. I. C., Calle

Américo Vespucio s/n, E-41092 Sevilla, Spain

e-mail: [email protected]

J. Garrido-Fernández • A. Pérez-Gálvez

Food Biotechnology Department, Instituto de la Grasa, C. S. I. C., Avenida Padre

García Tejero 4, E-41012 Sevilla, Spain

A. Garrido • M. Rendón-Martos

Reserva Natural Laguna de Fuente de Piedra, Consejería de Medio Ambiente, Junta de

Andalucía, Apartado 1, E-29520 Fuente de Piedra, Spain

CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING:

• Supplementary Figure 1 Categories to which the plumage colour of neck of wild

greater flamingos was allocated.

• Supplementary Figure 2 Approximate sites on feathers on which colour was

measured.

• Supplementary Figure 3 Two-dimensional HPLC chromatogram depicting

carotenoids detected in the uropygial secretions of greater flamingos.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1

3

2

1

Categories to which neck plumage colour of wild greater flamingos was allocated. (1)

very pale pink that at distance looks white, (2) pale pink, and (3) pink (photo credit:

Araceli Garrido).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2

Approximate sites on scanned neck feathers (indicated by dots) in which the colour was

measured.

•

• •

• •

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3

Two-dimensional HPLC chromatogram depicting carotenoids detected in the uropygial

secretions of greater flamingos. Peaks identification: 1 = canthaxanthin, 2 = cis-

canthaxanthin.