Sensation and Perception Lecture

-

Upload

jamesanthony -

Category

Documents

-

view

13 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Sensation and Perception Lecture

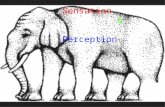

TRY THIS YOURSELF:

What do you see?

All outside information comes into us through our senses.

Sensation—the process of detecting, receiving, converting and transmitting information resulting from stimulation of sensory receptors.

Perception—the process of selecting, identifying, organizing and interpreting sensory input into a useful and meaningful mental representations of the world in the light of relevant memories from past experiences.

The basic function of sensation is detection of sensory stimuli, whereas perception generally involves interpretation of the same stimuli.

Our senses tell us something is out there. Our perception tell us what that something is.

In practice, sensation and perception are virtually impossible to separate, because they are part of one continuous process.

SENSATION IS THE PROCESS OF DETECTING AND ENCODING STIMULUS IN THE WORLD.

Vision (sense of sight) sensitive to LIGHT ENERGY

Auditory (sense of hearing)

stimulated by SOUND ENERGY

Olfaction (sense of smell) stimulates our nostrils by CHEMICAL ENERGY

Gustation (sense of taste)

Tactile (skin senses for pressure, temperature, pain)

THERMAL ENERGY

Vestibular (sense of balance)

Kinesthesia (sense of posture and movement)

Organic (sensation from internal organs such as hunger, thirst, drowsiness)

When neural impulses reach the particular area in the brain,

they are changed into meaningless bits of information called

sensation which involves the detection of sensory stimuli.

Transduction—after stimuli enter sensory organs, the sense

receptor will change/covert the stimulus into electrical signals

called neural impulses which are sent to the brain.

Information (e.g. light, sound)—activate our sense

receptors in the sensory organs which receive and

process sensory information from environment.

These meaningless bits of information are then changed into

meaningful and complete images called perception—the

interpretation of sensory stimuli.

Our sense organs translate physical energy from the environment into electrical impulses processed by the brain.

For example, light, in the form of electromagnetic radiation, causes receptor cells in our eyes to activate and send signals to the brain.

But we do not understand these signals as pure energy. The process of perception allows us to interpret them as objects, events, people, and situations.

Without the ability to organize and interpret sensations, life would seem like a meaningless jumble of colors, shapes, and sounds. A person without any perceptual ability would not be able to recognize faces, understand language, or avoid threats.

Sensory reduction—the process in which we filter and analyze sensory information before they are sent to the brain.

Why do we need to reduce the amount of sensory information we receive? So that the brain is not

overwhelmed with unnecessary information because it needs to be free to respond to stimuli that have meaning for survival.

All species have evolved selective receptors that suppress or amplify information to allow survival.

Sensory adaptation—

repeated or constant

stimulation decreases

the number of sensory

messages sent to the

brain, which causes

decreased sensation.

Threshold—refers to a

point above which a

stimulus is perceived

and below which it is

not perceived. It

determines when we

first become aware of

a stimulus.

SENSORY

THRESHOLDS

HOW CLOSE DOES AN

APPROACHING BUMBLE

BEE HAVE TO BE,

BEFORE YOU CAN HEAR

IT BUZZING?

HOW FAR DOES A

BREWING COFFEE POT

HAVE TO BE, FOR YOU

TO DETECT THE AROMA

OF THE COFFEE.

Difference threshold—or

just noticeable difference,

is the smallest change in

stimulus that we can detect.

Example: An artist might

detect the difference

between two very similar

shades of color

Absolute threshold—the smallest amount of stimulus that can be detected. When a stimulus has more

energy than the absolute threshold, we can detect its presence.

When a stimulus has less energy than the absolute threshold, we cannot detectits presence.

• Some established absolute thresholds are:

• vision: a candle flame 30 miles away on a clear night.

• hearing: a watch ticking 20 feet away

• taste: 1 teaspoon of sugar dissoved in 2 gallons of water

• smell: a single drop of perfume in a three-room house

• touch: a bee's wing falling a distance of 1 centimeter onto the cheek.

Absolute threshold

• PEOPLE HAVE DIFFERENT THRESHOLDS, BECAUSE SOME PEOPLE HAVE BETTER HEARING THAN OTHERS, AND SOME PEOPLE HAVE BETTER VISIONS THAN OTHERS.

The word perception

comes from the Latin

perception-,

percepio, meaning

"receiving, collecting,

action of taking

possession,

apprehension with

the mind or senses."

To identify a pattern of

sensory input is to

categorize it, in which

various expectations,

motives, experiences are

brought into play.

Example:

– If this is a mouse, it is

afraid of cat.

The first step in

perception is

selection—choosing

where to direct our

attention.

We do not perceive everything at once—we select certain objects to perceive while ignoring others.

Attention—is the

direction of

perception toward

certain selected

objects.

Attention is selective—we focus on

specific and important aspects of

experience while ignoring others.

Attention is

shiftable—we may

focus from one

specific object to

another.

Nature—whether visual or auditory, words or images, animate or inanimate objects

Reality—real, concrete things are more attention-getting than hypothetical, abstract or mental

Familiarity—people pay more attention to things that are familiar

Location/Proximity—we pay attention to things that are near than those that are far

Novelty—we pay attention to things that are new and different in contrast to what is customary

Suspense—people pay attention

to things that build suspense.

Conflict—people pay attention to

a good fight.

Humor—people pay attention to

things that are funny.

The vital—people nearly always

pay attention to matters that affect

their health, reputation, property, or

employment.

Activity—things that move, flash

or blink

Intensity—sounds that are louder

are more attention-getting than soft

music

Having selected

incoming

information, we

organize it into

patterns and

principles that will

help us understand

the world.

After selectively sorting through

incoming sensory information and

organizing it into patterns, the brain

uses this information to explain and

make judgments about the external

world. This is the final stage of

perception—interpretation.

Try to read the following passage:

Can you read this text when it is upside down?

Knowledge and experience are extremely

important for perception, because they

help us make sense of the input to our

sensory systems.

In the example above, you did not stop to

read every single letter carefully. Instead,

you probably perceived whole words and

phrases.

In mentally organizing stimuli, objects

that are physically close to one

another are grouped together or seen

as a unit.

In organizing stimuli,

elements that appear

similar in color,

lightness, texture,

shape, or any other

quality are grouped

together.

The law of continuity leads us to see a line as continuing in a particular direction, rather than making an abrupt turn.

We tend to favor smooth or continuous paths when interpreting a series of points or lines.

In organizing stimuli, we tend to fill in any missing part or incomplete figures and see them as complete figures.

In organizing stimuli, we tend to favor symmetrical objects or relationships.

Perception does not only

involve organization and

grouping, it also involves

distinguishing an object

from its surroundings.

Once an object is

perceived, the area around

that object (figure)

becomes the background.

In organizing a

stimuli, we tend to

automatically

distinguish between a

figure or foreground

(object with more

details) and a

ground (has less

detail).

Gestalt psychologists have devised ambiguous figure-ground relationships—that is, drawings in which the figure and ground can be reversed—to illustrate their point that the whole is different from the sum of its parts.

Reversible figures are

those objects that are so

shaped that both may

be seen as either the

figure or the ground—

the object that the

individual is set to

perceive will probably

be noticed first.

Interests or motives

Set of expectations

Socio-cultural factors

Past experiences

Situational context

ESP

• IT IS A PERCEPTION WITHOUT THE

MEDIATION OF THE SENSES. IT

INCLUDES:

– CLAIRVOYANCE – IS EXTRA SENSORY

AWARENESS OF OBJECTS.

– CONTACT BETWEEN THE MIND OF THE

PERSON AND ON THE OJECT.

– TELEPATHY – IS A THOUGHT

TRANSMISSION FROM ONE MIND TO

ANOTHER.

– PRECOGNITION – IS FOREKNOWLEDGE

OF SPECIFIC EVENTS WITHOUT ANY

RATIONAL MEANS.

– PSYCHOKINESIS – (MIND OVER MATTER)

INCLUDES MENTAL OPERATIONS THAT

INFLUENCES A MATERIAL BODY OR AN

ENERGY SYSTEM.