Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy Secondary to Dropped Head ...

Secondary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: ASCO Resource ... › wp-content › uploads › 2020 ›...

Transcript of Secondary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: ASCO Resource ... › wp-content › uploads › 2020 ›...

specialarticle

Secondary Prevention of CervicalCancer: ASCO Resource-StratifiedClinical Practice Guideline

executivesum

mary

Purpose To provide resource-stratified, evidence-based recommendations on the secondary prevention ofcervical cancer globally.

MethodsASCOconvenedamultidisciplinary,multinationalpanelofoncology,primarycare,epidemiology,healtheconomic, cancer control, public health, and patient advocacy experts to produce recommendations reflectingfour resource-tiered settings. A review of existing guidelines, a formal consensus-based process, and amodifiedADAPTE process to adapt existing guidelines were conducted. Other experts participated in formal consensus.

Results Seven existing guidelines were identified and reviewed, and adapted recommendations form theevidence base. Four systematic reviews plus cost-effectiveness analyses provided indirect evidence toinform consensus, which resulted in ‡ 75% agreement.Recommendations Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing is recommended in all resource settings; visualinspectionwithaceticacidmaybeused inbasicsettings.Recommendedage rangesand frequenciesbysettingare as follows: maximal: ages 25 to 65, every 5 years; enhanced: ages 30 to 65, if two consecutive negativetests at 5-year intervals, then every 10 years; limited: ages 30 to 49, every 10 years; and basic: ages 30 to 49,one to three timesper lifetime.Forbasicsettings,visualassessment is recommendedas triage; inothersettings,genotypingand/or cytologyare recommended. For basic settings, treatment is recommended if abnormal triageresultsarepresent; inothersettings,colposcopy isrecommended forabnormal triageresults.Forbasicsettings,treatment options are cryotherapy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure; for other settings, loop elec-trosurgical excision procedure (or ablation) is recommended. Twelve-month post-treatment follow-up isrecommended in all settings.WomenwhoareHIV positive should be screenedwithHPV testing after diagnosisandscreenedtwiceasmany timesper lifetimeas thegeneralpopulation.Screening is recommendedat6weekspostpartum inbasic settings; inother settings, screening is recommendedat 6months. Inbasic settingswithoutmass screening, infrastructure for HPV testing, diagnosis, and treatment should be developed.Additional information can be found at www.asco.org/rs-cervical-cancer-secondary-prev-guideline and www.asco.org/guidelineswiki.It is the viewof of ASCO that health care providers andhealth care systemdecisionmakers should beguidedbythe recommendations for the highest stratum of resources available. The guideline is intended to complement,but not replace, local guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this guideline is to provide expertguidance on secondary prevention with screen-ing for cervical cancer to clinicians, public healthauthorities, policymakers, and laypersons in allresource settings. The target population is womenin the general population at risk for developingcervical cancer (specific target ages depend onthe resource level).

There are large disparities regionally and globallyin incidence of and mortality resulting from cervi-cal cancer, in part because of disparities in theprovision of mass screening and primary preven-tion. Different regions of the world, both among

and within countries, differ with respect to accessto prevention and treatment.

Approximately 85% of incident cervical cancersoccur in less developed regions (also knownas low-and middle-income countries [LMICs]) aroundthe world, representing 12% of women’s can-cers in those regions. Eighty-seven percent ofdeaths resulting from cervical cancer occur inthese less-developed regions.1 Some of the re-gions in the world with the highest mortalityrates include the WHO Southeast Asia andWestern Pacific regions, followed by India andAfrica.1 As a result of these disparities, the ASCOResource-Stratified Guidelines Advisory Group

Jose Jeronimo

Philip E. Castle

Sarah Temin

Lynette Denny

Vandana Gupta

Jane J. Kim

Silvana Luciani

Daniel Murokora

Twalib Ngoma

Youlin Qiao

Michael Quinn

RengaswamySankaranarayanan

Peter Sasieni

Kathleen M. Schmeler

Surendra S. Shastri

Author affiliations appear atthe end of this article.

This guideline has beenendorsed by theInternational GynecologicCancer Society and theAmerican Society forColposcopy and CervicalPathology (DataSupplement).Clinical PracticeGuidelineCommittee Approved: July5, 2016

Reprint Requests: 2318Mill Rd, Ste 800,Alexandria, VA 22314;[email protected]’ disclosures ofpotential conflicts ofinterest and contributionsare found at the end of thisarticle.Corresponding author:AmericanSociety of ClinicalOncology,2318MillRd,Ste800, Alexandria, VA22314;e-mail:[email protected].

1 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

© 2016 by American Society of Clinical Oncology Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License

Copyright 2016 by .

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Secondary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: ASCO Resource-Stratified Clinical Practice Guideline

Guideline Question

What are the optimal method(s) for cervical cancer screening and the management of women withabnormal screening results for each resource level (ie, basic, limited, enhanced, maximal)?

Target Population

Women who are asymptomatic for cervical cancer precursors or invasive cervical cancer

Target Audience

Public health authorities, cancer control professionals, policymakers, obstetricians/gynecologists,primary care providers, lay public

Methods

A multinational, multidisciplinary Expert Panel was convened to develop clinical practice guidelinerecommendations on the basis of a systematic review of existing guidelines and/or an expert consensusprocess.

Authors’ note: It is the view of ASCO that health care providers and health care system decision makersshould be guided by the recommendations for the highest stratumof resources available. The guidelinesare intended to complement, but not replace, local guidelines.

Key Recommendations

Primary Screening

·Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing is recommended in all resource settings.

·Visual inspection with acetic acid may be used in basic settings.

·The recommended age ranges and frequencies in each setting are as follows:

◦Maximal: 25-65 years, every 5 years

◦Enhanced: 30-65 years, if two consecutive negative tests at 5-years intervals, then every10 years

◦Limited: 30-49 years, every 10 years

◦Basic: 30-49 years, one to three times per lifetime

Exiting Screening

·Maximal and enhanced: > 65 years with consistently negative results during past > 15 years

·Limited and basic: < 49 years, resource-dependent; see specific recommendations

Triage

·In basic settings, visual assessment for treatment may be used after positive HPV DNA testingresults.

◦If visual inspection with acetic acid was used as primary screening with abnormal results,women should receive treatment.

·For other settings, HPV genotyping and/or cytology may be used.

After Triage

·Women with negative triage results should receive follow-up in 12 months.

·In basic settings, women should be treated if there are abnormal or positive triage results.

(continued on following page)

2 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

chose cervical cancer as a priority topic forguideline development.

The primary goal of cervical cancer screening shouldbe—and the emphasis of these guidelines is—theaccurate detection and timely treatment of intra-epithelial precursor lesions of the cervix at a pop-ulation level for the purpose of cervical cancerprevention, rather than cancer control as for manyother cancers. This is because these precursorlesions are readily found and diagnosable and areeasily and effectively treated through outpatient ser-vices with minimal adverse events or sequelae.Earlier detection of cervical cancer at a lesser stageis also a benefit of screening, resulting in reduced

morbidityandmortality.However,many low-resourcesettings have little capacity in terms of surgery andradiotherapy to treat women with invasive cervicalcancer.2 Therefore, the ASCO Expert Panel that de-veloped this guideline (Appendix Table A1) empha-sizes the timely detection and treatment of cervicalprecancerous lesions before they become invasive.To achieve this, a high screening coverage and anorganized screening program are necessary.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes virtually allcervical cancer and its immediate precursors ev-erywhere in the world. High-quality screening pro-grams can lower the incidence of cervical cancerby up to 80%.3 In the past three decades, mass

THE BOTTOM LINE (CONTINUED)

·In limited settings, womenwith abnormal results from triage should receive colposcopy, if available,or visual assessment for treatment, if colposcopy is not available.

·In maximal and enhanced settings, women with abnormal or positive results from triage shouldreceive colposcopy.

Treatment of Women With Precursor Lesions

·Inbasic settings, treatment options arecryotherapyor loopelectrosurgical excisionprocedure (LEEP).

·In other settings, LEEP (if high level of quality assurance) or ablation (if medical contraindication toLEEP) is recommended.

·Twelve-month post-treatment follow-up is recommended for all settings.

Special Populations

·Womenwho areHIVpositive or immunosuppressed for other reasons should be screenedwithHPVas soon as diagnosed and screened twice as many times in a lifetime as the general population.

·Themanagement of abnormal screening results for womenwith HIV and positive results of triage isthe same as in the general population

·Women should be offered primary screening 6 weeks postpartum in basic settings and 6 monthspostpartum in other settings.

·Screeningmaybediscontinued inwomenwhohave receiveda total hysterectomy forbenigncauseswithnohistoryof cervicaldysplasiaorHPV.Womenwhohave receivedasubtotal hysterectomy (withan intact cervix) should continue receiving routine screening.

Qualifying Statement

In basic settingswithout currentmass screening, infrastructure forHPV testing, diagnosis, and treatmentshould be developed.

Additional Resources

More information, including a Data Supplement, a Methodology Supplement with information aboutevidencequality and strength of recommendations, slide sets, and clinical tools and resources, is availableat www.asco.org/rs-cervical-cancer-secondary-prev-guideline and www.asco.org/guidelineswiki. Patientinformation is available at www.cancer.net.

ASCO believes that cancer and cancer prevention clinical trials are vital to inform medical decisions andimprove cancer care and that all patients should have the opportunity to participate.

3 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

screening in high-resource settings has achievedthese reductions in cervical cancer incidence.4 Acervical cancer prevention program will affect theincidenceandmortality rates only ifwomenwithpos-itive screening results complete proper evaluationand treatment to prevent the progression to invasivecancer. Therefore, one of the critical evaluation indi-cators for any population-based program is the rateof completion of management and treatment inwomenwhorequire it,whichshould ideallybe100%.

In 2013 and 2014, WHO published guidelines onthe screening and treatment of precursor lesionsfor women in all settings; this guideline reinforcesthose recommendations. The screening modali-ties addressedbyWHOand this guideline, includecytology (also known as Papanicolaou, or Pap,test), visual inspection (eg, visual inspection withacetic acid [VIA]), and HPV DNA testing (screen-ing). For evaluation of positive results, the WHOguidelines include colposcopy, and for treatment,the guidelines recommend loop electrosurgicalexcision procedure (LEEP) of the transformationzone and ablative treatments. The screening testsare sometimes used and have been studied aloneand in combination. This ASCO guideline alsoaddresses screening in the vaccination era, self-sampling, and emerging screening technologies.

In some settings that have establishedmass screen-ing, cytology is the primary screeningmode; in othersettings, providers addHPVDNA testing (cotesting).Some countries and regions are moving toward orhave adopted primary HPV DNA testing or VIA.5,6

In low-resource settings, where screeningmay notcurrently be available, there is usually a shortageofpathologists, laboratories,colposcopistsandotherhealth providers, which limits the establishment ofa traditional screening program. For example, somecountries in sub-Saharan Africa have no patholo-gists7,8 and/or laboratories.9 However, HPV DNAtesting, which is more effective than the traditionalcytology screening test, may be introduced withoutpathology and laboratories. Therefore, less infra-structure is needed compared with cytology test-ing10 (see Cost and Policy Implications).

As HPV vaccination becomes more widespreadand the rate of HPV infection decreases, publichealth authorities must decide on screening pol-icies. Although prophylactic HPV vaccinationmaybe the ultimate cervical cancer prevention strategy,current HPV vaccines prevent infections but donot treat pre-existing infections and conditions.11,12

Moreover, bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vac-cines provide only partial protection against cer-vical cancer. Therefore, even if universal female

HPV vaccination could be rapidly deployed, therewould still be several generations of at-risk,HPV-infected women who would not benefitfrom—and would unlikely be targeted for—HPVvaccination. Without robust screening, millions ofwomen will die of cervical cancer before the impactof HPV vaccines on cervical cancer is observed.3

Thus, secondary prevention by cervical cancerscreening will be needed for the foreseeablefuture. (See Special Commentary on vaccinationand screening for an in-depth discussion.)

The diagnosis of cervical cancer precursors isbased on the pathologist’s judgment of the thick-ness of the transformed epithelium in biopsied orexcised tissue, which is graded (in order of in-creasing severity) as negative or as cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1 (CIN1; up toone-third thickness of epithelium), grade 2 (CIN2;up to two-thirds thickness), or grade 3 (CIN3; two-thirds thickness or greater). Other abnormal re-sults may include atypical squamous cells (ASC),ASC of undetermined significance (ASC-US), andadenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), the glandular equiv-alent of CIN3 and the precursor to adenocarci-noma. In this guideline, the termprecursor lesionsrefers to CIN2 or greater (> CIN2), defined as adiagnosis of CIN2 (the standard-of-care thresh-old that triggers treatment), CIN3, or AIS. CIN1 isnot considered a precursor lesion; most cases ofCIN1 regress within 6 years.13 CIN2 is consideredan equivocal precancerous diagnosis; that is, someinstances of CIN2 are CIN1 or HPV infection,14 andtherefore, treatment of all CIN2 may representovertreatment.15

ASCO has established a process for resource-stratified guidelines, which includes mixed methodsof guideline development, adaptation of the clinicalpractice guidelines of other organizations, andformal expert consensus. This article summa-rizes the results of that process and presentsresource-stratified recommendations that arebased, in part, on formal consensus and adap-tation from existing guidelines on the screen-ing, triage of screening results, and treatmentof women with cervical cancer precursor lesions(these guidelines are listed in Results and Ap-pendix Table A2).

ASCO uses an evidence-based approach to in-form guideline recommendations. In developingresource-stratified guidelines, ASCO has adoptedits framework from the four-tier approach (basic,limited, enhanced, maximal; Table 1) developedby the Breast Health Global Initiative and mademodifications to that framework on the basis of

4 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

the Disease Control Priorities 3.16,17 SeparateASCO resource-stratified guidelines provide guid-ance on the treatment of women with invasivecervical cancer2 and on primary prevention(forthcoming).

GUIDELINE QUESTIONS

This clinical practice guideline addresses thefollowing four overarching clinical questions: (1)What is the best method(s) for screening foreach resource stratum? (2) What is the best triagestrategy for women with positive results or otherabnormal (eg, discordant HPV/cytology) results?(3) What are the best management strategies forwomen with precursors of cervical cancer? (4)What screening strategy should be recommendedfor women who have received HPV vaccination?

METHODS

These recommendations were developed by anASCO Expert Panel with multinational and multi-disciplinary representation (Appendix Table A1).The Expert Panel met via teleconference and inperson and corresponded through e-mail. On thebasis of the consideration of the evidence, theauthors were asked to contribute to the develop-ment of the guideline, provide critical review, andfinalize the guideline recommendations. Membersof the Expert Panel were responsible for reviewingandapproving thepenultimate versionof theguide-line, which was then circulated for external reviewand submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for edito-rial review and consideration for publication. Thisguideline was partially informed by ASCO’s modified

Delphi Formal Expert Consensusmethodology, dur-ing which the Expert Panel was supplemented byadditional experts recruited to rate their agreementwith thedraftedrecommendations.Theentiremem-bership of experts is referred to as the ConsensusPanel (DataSupplementprovidesa listofmembers).All ASCO guidelines are ultimately reviewed andapproved by the Expert Panel and theASCOClinicalPractice Guideline Committee before publication.

The guideline development process was alsoinformed by the ADAPTE methodology as analternative to de novo recommendation devel-opment. Adaptation of guidelines is consideredby ASCO in selected circumstances, when one ormore quality guidelines from other organizationsalready exist on the same topic. The objective ofthe ADAPTE process is to take advantage of exist-ing guidelines to enhance efficient production,reduce duplication, and promote the local uptakeof quality guideline recommendations.

The ASCO adaptation and formal expert consen-sus processes begin with a literature search toidentify literature including candidate guidelinesfor adaptation. The panel used literature searches(from 1966 to 2015, with additional searches forliteraturepublished inspecificareas),existingguide-lines and expert consensus publications, some lit-erature suggested by panel members, and clinicalexperience as guides.

Adapted guideline manuscripts are reviewed andapproved by the Clinical Practice Guideline Com-mittee. The review includes the following two parts:methodologic review and content review. The

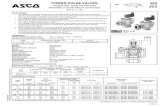

Table 1 – Four-Tiered Resource Settings for Secondary Prevention

Setting Definition

Basic Core resources or fundamental services absolutely necessary for any public health/primary health care system to function; basic-level services typically are applied ina single clinical interaction; screening is feasible for highest need populations.

Limited Second-tier resources or services thatproducemajor improvements inoutcomes, suchasincidence and cost effectiveness, but that are attainable with limited financial meansand modest infrastructure; limited-level services may involve single or multipleinteractions; universal public health interventions are feasible for a greater percentageof the population than primary target group.

Enhanced Third-tier resources or services that are optional but important; enhanced-level resourcesmay produce further improvements in outcomebut increase the number and quality ofscreening/treatmentoptionsand individual choice (perhapsability to trackpatientsandlinks to registries).

Maximal Mayusehigh-resource setting guidelines; high-level/state-of-the art resources or servicesthat may be used in some high-resource countries and/or may be recommended byhigh-resource setting guidelines that do not adapt to resource constraints; this shouldbe considered lower priority than in the other settings on the basis of cost impracticalityfor limited-resource environment.

NOTE. Data adapted.16,17

5 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

formerwascompletedby twoASCOstaffmembersand the latter by members of the Expert Panelconvened by ASCO.

The guideline recommendations were crafted, inpart, using the Guidelines Into Decision Supportmethodology and accompanying BRIDGE-Wiz soft-ware (Yale, New Haven, CT).19 Detailed informationabout the methods used to develop this guideline isavailable in theDataandMethodologySupplementsat www.asco.org/rs-cervical-cancer-secondary-prev-guideline.

The ASCO Expert Panel and guidelines staff willwork with the Steering Committee to keep abreastof any substantive updates to the guideline. On thebasis of the formal review of the emerging litera-ture, ASCO will determine the need to update thisguideline.

This is the most recent information as of thepublication date. Visit the ASCO Guidelines Wikiat (www.asco.org/guidelineswiki) to submit newevidence.

Guideline Disclaimer

The clinical practice guidelines and other guid-ance published herein are provided by ASCO toassist providers in clinical decision making. Theinformation herein should not be relied upon asbeing complete or accurate, nor should it beconsidered as inclusive of all proper treatmentsor methods of care or as a statement of thestandard of care. With the rapid development ofscientific knowledge, new evidence may emergebetween the time information is developed andwhen it is published or read. The information is notcontinually updated and may not reflect the mostrecent evidence. The information addresses onlythe topics specifically identified therein and isnot applicable to other interventions, diseases,or stages of diseases. This information does notmandate any particular course of medical care.Furthermore, the information is not intendedto substitute for the independent professionaljudgment of the treating provider, as the in-formation does not account for individual var-iation among patients. Recommendations reflecthigh, moderate, or low confidence that the recom-mendation reflects the net effect of a given courseof action. The use of words such as must, mustnot, should, and should not indicates that a courseof action is recommended or not recommended foreither most or many patients, but there is latitudefor the treating physician to select other courses ofaction in individual cases. In all cases, the selectedcourse of action should be considered by the

treating provider in the context of treating the indi-vidual patient. Use of the information is voluntary.ASCO provides this information on an as-is basisand makes no warranty, express or implied,regarding the information. ASCO specificallydisclaims any warranties of merchantability orfitness for a particular use or purpose. ASCOassumes no responsibility for any injury or dam-age to persons or property arising out of or relatedto any use of this information or for any errors oromissions.

Guideline and Conflict of Interest

The Expert Panel was assembled in accordancewith ASCO’s Conflict of Interest Policy Implemen-tation for Clinical Practice Guidelines (“Policy,”foundat http://www.asco.org/rwc). Allmembers ofthe Expert Panel completed ASCO’s disclosureform, which requires disclosure of financial andother interests, including relationships with com-mercial entities that are reasonably likely to expe-rience direct regulatory or commercial impact as aresult of promulgation of the guideline. Categoriesfor disclosure include employment; leadership;stock or other ownership; honoraria; consultingor advisory role; speaker’s bureau; research fund-ing; patents, royalties, other intellectual property;expert testimony; travel, accommodations, ex-penses; and other relationships. In accordancewith the Policy, the majority of the members of theExpert Panel did not disclose any relationshipsconstituting a conflict under the Policy.

RESULTS

Literature Search

As part of the systematic literature review, thePubMed, SAGE, Cochrane Systematic Review,andNational Guideline Clearinghouse databaseswere searched for literature and guidelines,systematic reviews, and meta-analyses thatwere about screening for, or treatmentof, precursorlesions; developed by multidisciplinary content ex-perts as part of a recognized organizational effort;and published between 1966 and 2015.

Literature searches based on prespecified criteriaaswell as updates of literature searcheswith termsused by other guidelines were conducted, and atitle screen was completed and abstract review be-gun.However, because several high- andmoderate-quality guidelines were found, the full text reviewand data extraction steps of the systematic reviewwere not completed.

Searches for cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs)were also conducted and titles, abstracts, and full

6 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

texts were reviewed. Forty-one CEAs were found(this guideline cites three from these results,20-22

andpanelmemberssuggestedanadditionalstudy23).Articles were excluded from the systematic review ifthey were meeting abstracts, books, editorials, com-mentaries, letters, news articles, case reports, ornarrative reviews.

Methods and Results of the ASCO UpdatedLiterature Search

A search for new evidence was conducted byASCO guidelines staff to identify relevant randomizedclinical trials, systematic reviews,meta-analyses,and guidelines published since the Cancer CareOntario (CCO) and WHO guidelines were com-pleted. Following the strategies described in theWHO guidelines, PubMed and EMBASE data-bases were searched from 2011 to December2014 in July 2015. The search was restrictedto articles published in English, and the ASCOguideline inclusion criteria were applied to re-view of the literature search results. Titles werereviewed; as described earlier, evidence re-views conducted for other societies’ guidelineswere used as the evidence base.

Sixteen guidelines were found in the search, andtheir currency, content, and methodology werereviewed. On the basis of content and methodol-ogy assessments, the Expert Panel chose sevenguidelines as the evidentiary basis for the guidelinerecommendations; these guidelines were fromthe American Cancer Society (ACS)/AmericanSociety for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology(ASCCP)/American Society for Clinical Pathology(ASCP)24,25; a second ASCCP-led effort26; an-other US-based multisociety group’s guideline,referred to here as Huh et al6; CCO27; a Europeanguideline, referred to as von Karsa et al5; and twoguidelines from the WHO.28,29 (Note that at thetimeof thiswriting, theUSPreventiveServices TaskForce was updating its guidelines.30) AppendixTable A2 contains links to these guidelines.

The existing guidelines cover different screeningtests, including cytology, visual inspection, andHPV DNA testing; different modes of sam-pling cervical cells (clinician and self-sampling);different strategies when screening results areabnormal, also known as triage; the screen-and-treat strategy; the management of > CIN2; andthe follow-up of women after receiving treat-ment of > CIN2, as well as secondary preven-tion for women in subpopulations, such as thosewith HIV.

This ASCO guideline reinforces selected recom-mendations offered in the ACS/ASCCP/ASCP,ASCCP, CCO, WHO, von Karsa et al,5 and Huhet al6 guidelines and acknowledges the effortput forth by the authors and aforementionedsocieties to produce evidence- and/or consensus-based guidelines informing practitioners andinstitutions.

These guidelines were published between 2011and 2015. Six were based completely or in part onsystematic reviews.5,24-29 TheWHO guideline hasthe largest global constituency andmakes recom-mendations for resource-constrained areas. Allthe other guidelines were developed in maximalresource–level settings. Various types and levels ofevidence were used to support these guidelines.Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have beenconducted on the type of test for primary screeningand the treatment of precursor lesions. Formost ofthe other clinical questions, these guidelines werebased on nonrandomized comparative studies,observational data, pooled analyses, modeling,and expert opinion. Appendix Table A2 lists linksto and the Data Supplement provides an overviewof the guidelines, including information on theirclinical questions, target populations, developmentmethodology, and details of key evidence.

ASCO Methodologic Review

The methodologic review of the guidelines wascompleted by two ASCO guideline staff membersusing the Rigor of Development subscale of theAppraisal of Guidelines for Research and EvaluationII instrument.31 The score for the Rigor of Develop-ment domain is calculated by summing the scoresacross individual items in the domain and standard-izing the total score as a proportion of the maximumpossible score. Detailed results of the scoring andthe Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Eval-uation II assessment process for this guideline areavailable in the Methodology Supplement.

FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The recommendations were developed by a mul-tinational, multidisciplinary group of experts usingevidence from existing guidelines, supplementaryliterature, and clinical experience as guides. TheASCOExpert Panel underscores that public healthofficials and health care practitioners who imple-ment the recommendations presented in thisguideline should first identify the available re-sources in their local and referral facilities andendeavor to provide the highest level of carepossible with those resources.

7 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

Maximal-Resource Setting

In maximal-resource settings, cervical cancerscreeningwithHPVDNA testing should be offeredevery 5 years from ages 25 to 65 years. On anindividual basis, women may elect to receivescreening until 70 years of age (Type: evidencebased for test, interval, and age [25 to 65 years];Type: formal consensus based [until age 70 years];Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommenda-tion: strong).

Women who are> 65 years of age who have hadconsistently negative screening results during thepast > 15 years may cease screening. Womenwho are 65 years of age and have a positive resultafter age 60 should be reinvited to undergoscreening 2, 5, and 10 years after the last pos-itive result. If women have received no or irreg-ular screening, they should undergo screeningonce at age 65 years, and if the result is negative,they should exit screening (Type: evidencebased; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strengthof recommendation: moderate).

If the results of the HPV DNA test are positive,clinicians should then perform triage with reflexgenotyping forHPV16/18 (withorwithoutHPV45)and/or cytology as soon as HPV test results areknown (Type: evidence based; Evidence quality:high; Strength of recommendation: strong). If tri-age results are abnormal (ie,>ASC-US or positivefor HPV 16/18 [with or without HPV 45]), womenshould be referred to colposcopy, during whichbiopsies of any acetowhite (or suggestive of can-cer) areas should be taken, even if the acetowhitelesion might appear insignificant. If triage resultsare negative (eg, primary HPV positive and cytologytriage negative), then repeat HPV testing at the12-month follow-up (Type: evidence based; Evi-dence quality: intermediate; Strength of recom-mendation: strong).

If HPV test results are positive at the repeat12-month follow-up, refer women to colposcopy.If HPV test results are negative at the 12- and24-month follow-ups or negative at any consecu-tiveHPV test 12monthsapart, thenwomenshouldreturn to routine screening (Type: evidencebased;Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommenda-tion: strong).

Women who have received HPV and cytologycotesting triage and have HPV-positive resultsand abnormal cytology should be referred forcolposcopy and biopsy. If results are HPV pos-itive and cytology normal, repeat cotesting at12 months. If at repeat testing HPV is still pos-itive, patients should be referred for colposcopy

and biopsy, regardless of cytology results (Type:formal consensus based; Evidence quality: inter-mediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

If the results of the biopsy indicate that womenhave precursor lesions (> CIN2), then cliniciansshould offer LEEP (if there is a high level of qualityassurance [QA]),32 or where LEEP is contraindi-cated, ablative treatments may be offered. (Type:evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strengthof recommendation: strong).

After women receive treatment of precursor le-sions, follow-up should consist of HPV DNA testingat 12 months. If 12-month results are positive,continue annual screening; if not, return to rou-tine screening (Type: formal consensus based;Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of rec-ommendation: moderate).

Source guidelines and discussion. The age rangefor HPV testing was modified from guidelines byHuh et al6 that based the age of initiation on theAddressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnos-tics (ATHENA) RCT used for US Food and DrugAdministration registration.33 Adding the years 25to 29 to the starting age recommended by CCOand WHO (30 years) is from the evidence thatHPV testing benefits women who are HPV neg-ative, including those age 25 to 29 years.6

Screening is not recommended for women un-der the age of 25 given the lack of evidence of thebenefit of decreased cancer risk and the poten-tial harms of screening and overtreatment. Forexample, as described in the Huh et al6 guideline,there is a lower 3-year cumulative incidence ratefor women whose results were high-risk HPVtype (hrHPV) negative. The age of cessation at65 years is suggested on the basis of existingguidelines. In general, the criteria for exitingscreening are determined primarily on resourceavailability and the average life span of women ineach setting, which is matched with the currentknowledge of the HPV infection-to-dysplasiaprocess. As life expectancy in maximal resourcesettings (eg, Organization for Economic Coop-eration and Development countries) increases,and where estimated incidence rates for womenages 60 to 64 and 65 to 69 years are similar(16.6 and 16.1 per 100,000, respectively),1 womenand their doctors may make individualized de-cisions to extend screening up to 70 years of age.For example, women who are 65 to 70 years old,have received screening, and have a history ofpositive screening (HPV, cytology, or VIA) testresults in the last 5 years may be reinvited toscreening until 70 years of age.

8 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

The choice of HPV DNA testing is supported byevidence of its effectiveness as a screening testand by several existing guidelines from developersincluding WHO, von Karsa et al,5 Huh et al,6 andCCO. HPV DNA testing is more sensitive thancytology.6 The interval of 5 years is based on theWHO, CCO, and European guidelines (CCO rec-ommendations were specific to women older thanage 30 years). There have been 10 RCTs on pri-mary HPV testing. (The CCO guideline cites sevenRCTs published between 2007 and 2010, includ-ing New Techniques in Cervical Cancer [NTCC], ARandomized Controlled Trial of HPV Testing inPrimaryCervicalScreening[ARTISTIC],Population-Based Screening Study Amsterdam [POBASCAM],Swedescreen, Finnish Public Health Trial [FPHT],Sankaranarayanan et al, and Canadian CervicalCancer Screening Trial [CCCaST].27) The Huhet al6 guidance cites pooled analyses of EuropeanRCTs (Dillner et al,34 which included seven pro-spective studies, andRoncoet al,35which includedfour of the trials in CCO that had data fromtwo rounds of screening [ARTISTIC, POBASCAM,NTCC, and Swedescreen published between2007 and 2012]), the Vrije Universiteit Medi-cal Centre-Saltro (VUSA)-Screen study,36 theATHENA RCT, and a Kaiser database. Roncoet al35 mentioned FOCAL, listed as ongoing byCCO, which was not included in the Huh et al6

guidance. Selected RCT data have been extract-ed in the Data Supplement.

Cotesting is an option, as recommended by theACS/ASCCP/ASC pathology guideline; however,the added value on the basis of increased costsis limited. Evidence for this statement is found inthe Huh et al6 guideline and a 2014 publicationincluding CEA from the ARTISTIC trial, whichfound that strategies using primaryHPV screeningwere more cost-effective than those using cotest-ing (eg, the rate of primary HPV screening withcytology triage and repeat HPV at 12 or 24monthswas 22% for vaccinated cohorts and 18% in un-vaccinated cohorts).37,38

In maximal-resource settings, mass screeningshould be available to the entire target populationandshouldaim tocoverat least80%ofwomenage25 to 70 years. Readers should note that there aremore than 100 molecular tests for the detectionof HPV; however, population-based screeningprograms should only use HPV tests that showclinical utility (which ASCO considers the highestlevel of evidence for biomarkers39), are properlyvalidated,40,41 and are approved by nationaland/or international regulatory agencies, suchas US Food and Drug Administration approval,

European Union CE marking, WHO endorsement/prequalification, or other country- or regional-levelregulatory agencies. The tests should also haveconfirmed good manufacturing practices.

Women who are 65 to 70 years of age and do nothave a history of> CIN3 do not need to be offeredscreening if they have had two or more consecu-tive negative HPV test results or three or morenegative cytology test results andonly negative testresults in the past 15 years.

If there are positive results from colposcopy, theoptions for the treatment of women with precursorlesions include LEEP, which is the first choice inmaximal and enhanced settings, and various ab-lative treatments including cryotherapy, cold co-agulation, or laser, which should all meet a highlevel of QA metrics (listed in Table 2).29,32 Cryo-therapy is not recommended in the maximal set-ting. LEEP is preferred, in part, because it providestissue for a histopathologic diagnosis. However,LEEP technology and trainingmaynot be availablein lower resource settings and/or have contraindi-cations. The Massad et al26 and WHO guidelines,citing RCTs and Cochrane reviews, and a morerecent (2013) Cochrane review42 showed mini-mal differences between treatments. The WHOguideline states there is low evidence of treatmentversus no treatment, mostly pooled results of non-comparative, nonrandomized studies. There areno RCTs specifically on HPV after LEEP.43 Thereis a paucity of prospective, comparative data onother treatment and follow-up strategies to guiderecommendations on post-treatment follow-up.26

Therefore, on the basis of formal consensus, thisguideline recommends follow-up HPV DNA test-ing at 12 months after one of these treatments.

Enhanced-Resource Setting

In enhanced-resource settings, cervical cancerscreeningwithHPVDNA testing should be offeredto women 30 to 65 years of age every 5 years (ie,second screen 5 years from the first; Type: evi-dence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength ofrecommendation: strong). If there are two consec-utive negative screening test results, subsequentscreening should be extended to every 10 years(Type: formal consensus based; Evidence quality:intermediate-low; Strength of recommendation:moderate).

Women who are> 65 years of age who have hadconsistently negative screening results duringthe past> 15 yearsmay cease screening.Womenwho are 65 years of age and have a positive resultafter age 60 years should be reinvited to undergo

9 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

screening 2, 5, and 10 years after the last positiveresult. If women have received no or irregularscreening, they should undergo screening onceat age 65 years, and if the result is negative, theyshould exit screening (Type: formal consensusbased; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recom-mendation: weak).

If the results of the HPV DNA test are positive,clinicians should then perform triage with HPVgenotyping forHPV16/18 (withorwithoutHPV45)and/or reflex cytology (Type: evidence based; Ev-idencequality: high; Strengthof recommendation:strong). If triage results are abnormal (ie, > ASC-US or positive for HPV 16/18 [with or without HPV45]), women should be referred to colposcopy,during which biopsies of any acetowhite (or sug-gestive of cancer) areas should be taken, even ifthe acetowhite lesionmight appear insignificant. Iftriage results are negative (eg, primary HPV pos-itiveandcytology triagenegative), then repeatHPVtesting at the 12-month follow-up (Type: evidencebased; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength ofrecommendation: strong).

If HPV test results are positive at the repeat12-month follow-up, refer women to colposcopy.

If HPV test results are negative at the 12- and24-month follow-ups or negative at any consecutiveHPVtest12monthsapart, thenwomenshould returntoroutinescreening(Type:evidencebased;Evidencequality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

If the results of colposcopyandbiopsy indicate thatwomen have precursor lesions (> CIN2), thenclinicians should offer LEEP (if there is a high levelof QA) or, where LEEP is contraindicated, ablativetreatmentsmay be offered (Type: evidence based;Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommenda-tion: strong). After women receive treatment ofprecursor lesions, follow-up should consist of HPVDNA testing at 12months. If 12-month results arepositive, continue annual screening; if not, returnto routine screening (Type: formal consensusbased; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strengthof recommendation: moderate).

Source guidelines and discussion. In enhanced-resource settings, which refer to most programsin urban areas of middle-income countries, pub-lic health authorities may narrow the screeningage range to 30 to 65 years; this is in agreementwith the CCO guidelines. There is insufficient evi-dence on the best age of cessation.44 The exten-sion to 10 years after negative tests is based onthe von Karsa et al5 guideline.

The cost analysis study by Beal et al21 (2014) wasconducted from theperspective ofMexicanhealthcare institutions and compared the following fourscreening plus triage strategies: cytology alone,hrHPV with reflex cytology, hrHPV with moleculartriage, and cotesting with molecular triage. Thestudy found that when the base case was cytologyalone, hrHPV with molecular triage had the low-est incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)(–819 v –108.99 v –537 for hrHPVwithmoleculartriage, hrHPV with cytology triage, and cotesting,respectively), with a cost at US$91.5 million (2013US dollars). This strategy resulted in fewer womenundergoing colposcopy. (Note that Mexico’s 2013gross national income per capita was $15,620[WorldBankdata,grossnational incomepercapita,purchasing power parity].45)

As with the maximal-resource setting recommen-dations, if a womanhas a history of positive screen-ing (HPV, cytology, or VIA) test results in the past5 years, she should be reinvited to screening. Theinterval may increase to 10 years in enhanced set-tings after two negative tests and is a modificationof the von Karsa et al5 guidelines, which give theupper limit of 10 years after a negative test. This isalso because HPV testing in older women yields ahigher specificity.46 In the enhanced setting, if HPV

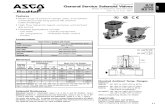

Table 2 – Quality Assurance Criteria for Treatment of Precursor Lesions

Treatment Modality Criteria Source

LEEP The results of VIA or VILI or colposcopypositive, not suspicious for cancer unlessLEEP for biopsy and not treatment, canidentify full extent of external lesions, etc,. 12 weeks postpartum

Jhpiego32

Sufficient training of provider, with ability tohandle complications

WHO4

Absolute contraindications to LEEP ASCO Expert Panel

Pregnancy

Acute cervicitis

Bleeding or coagulation disorders

Patient unwillingness

Relative contraindications to LEEP

Patient , 3 months postpartum

Recurrence in a postcervical conizationcase

Young patient with a small cervix

Strong suspicion of microinvasive cancer

Ablation Lesion covers , 75% of cervix, lesion doesnot enter endocervical canal, patient doesnot have positive ECC, entire lesion can bevisualized and covered by the cryotherapyprobe, no suspicion for invasive cancer

WHO29

Abbreviations: ECC, endocervical curettage; LEEP, loop electrosurgical excision procedure;VIA, visualinspection with acetic acid; VILI, visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine.

10 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

genotyping is available, use this for triage. If HPVgenotyping is not available, reflex cytology may beused, because the low predictive value of a pos-itive HPV DNA test for finding > CIN2 can beraised to the level of cytology by cytologic triage ofHPV-positive women.47,48 Cytology for triage isrecommended by the CCO and von Karsa et al5

guidelines.

Follow-up after triage is the same as in maximal-resource settings. For management of precursorlesions, theExpert Panel recommendsusing LEEPas a first choice, but if LEEP is not available oris contraindicated and the patient is eligible forablation (Table 2),29 then the clinician may useablation. The other recommendations are thesame as in the maximal setting.

Limited-Resource Setting

Cervical cancer screening with HPV DNA testingshould be offered to women age 30 to 49 yearsevery 10 years, corresponding to two to three timesper lifetime (Type: evidence based [age range],Type: formal consensus based [interval]; Evidencequality: intermediate; Strength of recommenda-tion: moderate).

If the results of the HPV DNA test are positive,clinicians should then perform triage with reflexcytology (quality assured) and/or HPV genotypingfor HPV 16/18 (with or without HPV 45) or withvisual assessment for treatment (VAT; for cytologyand genotyping: Type: evidence based; Evidencequality: high;Strengthof recommendation: strong;for VAT: Type: formal consensus based; Evidencequality: low; Strength of recommendation: weak).

If cytology triage results are abnormal (ie,> ASC-US), women should be referred to quality-assuredcolposcopy (the first choice, if available and ac-cessible), duringwhich biopsies of any acetowhite(or suggestive of cancer) areas should be taken,even if the acetowhite lesion might appear in-significant. If colposcopy is not available, thenperform VAT (Type: evidence based; Evidencequality: intermediate; Strength of recommenda-tion: moderate).

If HPV genotyping or VAT triage results are posi-tive, then women should be treated. If the resultsfrom both of these forms of triage are negative,then repeatHPV testing at the 12-month follow-up(Type: evidence based; Evidence quality: high;Strength of recommendation: strong). If test re-sults arepositive at the repeat 12-month follow-up,then women should be treated (Type: formalconsensus based; Evidence quality: intermedi-ate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

For treatment, clinicians should offer ablationif the criteria are satisfied; if not and resourcesare available, then offer LEEP (if there is a highlevel of QA; Table 2; Type: evidence based;Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommen-dation: strong). After women receive treatmentof precursor lesions, follow-up should consistof the same testing at 12 months (Type: formalconsensus based; Evidence quality: intermedi-ate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

CEAs. The interval of 10 years (three times perlifetime) is supported by a CEA23 found in ASCO’sliterature search for CEAs and was based on datafromdemonstrationprojects in SouthAsia, CentralAmerica, and East Africa. The objective of thisstudy was analyzing cost-effectiveness of vari-ous tests (HPV DNA test, VIA, and cytology),age ranges, screening intervals, and numbers ofscreens per lifetime in limited-resource settings.This analysis supported the WHO guidelines forthe age range of 30 to 49 years and found thatHPV DNA testing three times per lifetime every10 years starting at age 30 was a cost-effectivestrategy with attractive ICERs of 350 to 580 (inter-national dollars) per life-year saved (LYS), varyingby region. Cost of screening three times perlifetime with intervals of 5 years ranged from$180 to $1,600 international dollars per LYS(starting at age 30 years in India and at age25 years in Uganda).23

Source guidelines and discussion. In limited-resource settings, which often correspond to ruralareas in middle-income countries, most of therecommendations are based on the WHO guide-line. The triage of positive screening results willdepend on resources and the sample availablefrom the screening. If there is sufficient samplefrom the primary test and genotyping is availableor if genotyping is concurrent, that should beused, as recommended by the Huh et al6 guide-line. If not and if cytology meets QAmetrics,5 thatmay be used. If cytology does not meet the QAmetrics, then VAT should be used, as recom-mendedbyWHO.28 If cytology results arepositive,then women may receive quality-assured colpo-scopy, if available; otherwise, see and treat on thebasis of the triage results. Although it was not withinthe scope of this guideline to develop de novo orformally review others’ recommendations on QA forcolposcopy, groups that have addressed this in-clude theNationalHealth Service49 and theSocietyof Canadian Colposcopists.50 In addition, the 2011International Federation for Cervical Pathology andColposcopy Nomenclature is used worldwide.51

11 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

If a woman has a history of abnormalities (eg,repetitively HPV-positive results) and recallingwomen for follow-up after abnormal results is achallenge, the womanmight have an elevated riskfor > CIN2, and it might be cost-effective to offertreatment in limited or basic settings. (However, inenhanced and maximal settings, when recall ismore feasible, further tests should be performedbefore treatment.)

The recommendation to follow-up other results ifHPV genotyping is not available is a modificationof CCO and WHO recommendations. The man-agement of precursor lesions is based on theASCCP26andWHOguidelines29; the latter supportsperforming LEEP. On the basis of each authoritythat provides screening CEA, women older thanage 49 years with no previous screening may beoffered screening, after the priority age group (30 to49 years) is covered.

Basic-Resource Setting

If HPV DNA testing for cervical cancer screeningis not available, thenVIA shouldbeofferedwith thegoal of developing health systems and moving topopulation-based screening with HPV testing atthe earliest opportunity. Screening should be of-fered to women age 30 to 49 years at least once perlifetime but not more than three times per lifetime(Type: evidence based; Evidencequality: interme-diate; Strength of recommendation: strong). If theresults of available HPV testing are positive, clini-cians should then perform VAT followed by treat-ment with cryotherapy and/or LEEP, dependingon the size and location of the lesion (Type: for-mal consensus based; Evidence quality: low;Strength of recommendation: moderate). If pri-mary screening is VIA and results are positive, thentreatment shouldbeofferedwith cryotherapyand/orLEEP, depending on the size and location of thelesion (Type: evidence based; Evidence quality:intermediate52; Strength of recommendation:moderate).

Afterwomen receive treatment of precursor lesions,then follow up with the available test at 12 months.If the result is negative, then women should return toroutine screening (Type: formal consensus based;Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recom-mendation: moderate).

CEAs. In addition to the study by Campos et al23

discussed in limited-setting recommendations,the study by Shi et al20 (found in ASCO literaturesearch for CEAs) was a CEA that involved severalsubstudies that compared HPV versus VIA versusVIA/visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine once or

twice per lifetime or at routine intervals for primarytesting in rural China. The outcomes includedcost-effectiveness, incidence, mortality, and opti-mal age ranges. The investigators found that thelowest cost-effectiveness ratio (CER) for screening(compared with no intervention) was associatedwith VIA once per lifetime at age 35 years, and thesecond lowest was with VIA twice per lifetime (atage35 to 45 years). The average lifetime reductionin cancer mortality was 8% for once per lifetime forVIA and 12% for HPV; twice per lifetime reductionswere 16% and 24%, respectively. “Depending onthe test technology used, and assuming a partic-ipation rate of approximately 70%, we found thatonce-lifetime screening at age 35 years wouldreduceage-standardisedcervical cancermortalityin the population by 8-12% over the long term,with a CER of $557-959 per LYS. Regular screen-ing at a feasible age-standardised participationrate of 62% in women aged 30-59 years wouldreduce cervical cancer mortality by 19-54%,with a CER of $665-2,269 per LYS.”20(p14) (TheWorld Bank currently categorizes China as anupper-middle-income economy.53)

Source guidelines and discussion. These recom-mendations are based on the WHO guideline. Inbasic settings, where there is no mass screeningandnoculture of screening, VIAmaybeused,withthe goal of moving to population-based screeningwith HPV testing at the earliest opportunity. Therehave been mixed results regarding VIA as primaryscreening. A clusterRCTonVIA involving151,538women in India was published after the WHOguidelines.54 Outcomes including cervical cancermortality and incidence for 75,630 women re-ceiving four rounds of VIA plus cancer educationwere compared with those of 76,178 women re-ceiving cancer education alone. The authors havepublished 12 years of follow-up. Age-adjustedrates (AARs) for incidence of cervical cancer were29 (95% CI, 24.5 to 33.4) for VIA plus educationcompared with 29.4 (95% CI, 27.2 to 31.7) foreducationalone(incident rateratio,0.8-1.2;P5 .79).AARs for cervical cancer mortality were 14.4 (95%CI, 12.7 to 16.2) for VIA plus education comparedwith 19.8 (95% CI, 17.8 to 21.8) for educationalone, with an incident rate ratio of 0.69 (95% CI,0.54 to 0.88; P 5 .003). All-cause mortality AARswere 1,340.5 (95% CI, 1,321.2 to 1,359.6) for VIAplus education compared with 1,391.3 (95% CI,1,372.1 to 1,410.4) for education alone, and themortality rate ratio was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.79 to 1.1;P5 .41). (All figureswere for100,000person-yearsof observation.)54 An earlier four-arm clusterRCT conducted in India compared HPV testing,

12 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

cytology, VIA, and standard care; it was publishedwith 8 years of follow-up.55 In that study, the sta-tistically significant outcomes were in the HPVtesting arm, but not in the VIA arm. The hazardratio for mortality was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.33 to 0.83)with HPV versus control. The hazard ratios for theincidence of stage II or higher cervical cancer were0.47 (95% CI, 32 to 0.69) for HPV versus controland 1.04 (95% CI, 0.72 to 1.49) for VIA versuscontrol.

Screening with VIA helps build infrastructure andbrings women into medical care and screening(eg, in Bangladesh and Tamil Nadu, India).56,57 Ifscreening is not started, the infrastructure will notdevelop for HPV testing. This is recommendedwhile recognizing that follow-up opportunitiesmaybe limited. Regions should build toward havingsystems in place to diagnose and treat womenwith positive results and invasive cancer. For publichealth entities that initiate VIA for primary screen-ing, it is crucial to invest significant effort to usevalidated training andvalidationprocedures. Theseentitiesmust haveaplan for quality control of trainedVIA evaluators’ performance.

After the establishment of such patterns, publichealth systems can introduce HPV testing. As thesesystemsdevelop infrastructure for population-basedscreening, parallel development of systems for di-agnosis and treatment of invasive cancer needs tooccur.Concurrentlywith thedevelopmentof screen-ing programs, programs should develop the capac-ity toassesswomenwithsymptoms, includingwomenoutside of the target age range. In addition, the in-troduction of VIA screeningmay lead to identificationof symptoms and women with symptoms seekingcare. There may be high levels of screen-detectedcancers on the first round of screening (many pre-sumably in symptomatic women). Downstaging canbe valuable too if treatment is available. The recom-mendations for age range, screening interval, tri-age, andspecial populations in thebasic setting aremodifications of the WHO recommendations.28

Follow-up of abnormal results and treatment ofwomen with > CIN2 follow the WHO recommen-dations on this condition.29

Recommendations for Special Populations

Recommendation SP1a: Women who are HIVpositive. Women who are HIV positive shouldbegin screening with HPV testing, every 2 to3 years, as soon as they receive an HIV diagno-sis. The recommended frequency depends onthe resource level; in general, it should be twiceas many times in a lifetime as in the generalpopulation (Type: formal consensus based;

Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommenda-tion: weak).

The recommended frequencies, according to re-source setting, are as follows:

·Maximal: Women should be screened forHPV approximately every 2 to 3 years.

·Enhanced: Women should be screened forHPV at intervals of 2 to 3 years, then, ifnegative, every 5 years (approximately eightscreenings per lifetime).

·Limited: Women should be screened forHPV at intervals of every 2 to 3 years andtwice as many times in a lifetime as in thegeneral population (approximately four tosix screenings per lifetime).

·Basic: If HPV testing is available, womenwithHIV should be screened for HPV as early aspossible starting at age 25, every 3 years ifthe test results are negative initially; ap-proximately twice per lifetime. If HPV testingis not available, use VIA at the same intervals(Type: evidence-based; Evidence quality:low; Strength of recommendation: weak).

The management of abnormal results of screeningfor women with HIV and positive results of triageis the same as in the general population (Type:formal consensus based; Evidence quality: low;Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation SP1b: Women who areimmunosuppressed—all settings. Women whoare immunosuppressed for any reason otherthan HIV should be offered the same screeningas women who are HIV positive (Type: formalconsensus based; Evidence quality: insuffi-cient; Strength of recommendation: weak).

Discussion of SP1a and SP1b. There is insufficientevidence regarding screening women with HIV;only theWHOguidelinemadespecific recommen-dations regarding thesewomen. There are no datato informscreening forwomenwhoare immunosup-pressed for other reasons. In general, these recom-mendations agreewith theWHOguidelines,with thegrateful acknowledgment of thepanel.52 In addition,Forhanet al58performedasystematic reviewonsee-and-treat strategies for women with HIV in LMICsand found a lack of long-term outcome data (includ-ing morbidity and mortality and some HIV-specificoutcomes). All the studies found in the systematicreview by Forhan et al58 were observational.

Further, Vanni et al59 used a model-based ap-proach to compare 27 strategies of primary HPV

13 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

testing or cytology with triage of cytology, HPV, orcolposcopy, and each of these combinations at6 months, 1 year, or 2 years, for women with HIVinBrazil, which is characterized as amiddle-incomecountry. The authors found that once-yearly HPVtesting with cytology triage would be the most cost-effective strategy for women with HIV in Brazil withCER results ofUS$4,911per LYS,with the thresholdof Brazil’s per capita gross domestic product ofUS$8,625 per LYS.59 (The World Bank currentlycategorizes Brazil as an upper-middle-incomeeconomy.53)

RecommendationSP2a:Womenwhoarepregnant—all settings. Pregnant women should not receivescreening.

Recommendation SP2b: Women who arepostpartum—all settings. Women who are post-partum should be screenedwith VIA 6 weeks afterdelivery in basic settings. In other settings, HPVtesting is recommended 6 months after delivery,unless there is uncertainty about completion offollow-up, inwhichcase screening at 6weeks afterdelivery is advised (Type for both: formal consen-sus based; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strengthof recommendation: weak).

Discussion of SP2a and SP2b. There is no evi-dence available to support evidence-based rec-ommendations for women who are pregnant orpostpartum; therefore, the recommendations arebased on formal consensus. There is some in-dication that as a result of immunechangesduringpregnancy, some pregnant women may have in-creasedHPV, which can subside after pregnancy.Performing HPV testing during this time of eleva-tion may then produce inaccurate results. The testspecificity increases with time. However, in somesettings, loss to follow-up may be a concern, andbecausewomenmayalready be seeing cliniciansfor a postpartum and/or new baby visit at 6 weeks,the recommendation presents an opportunity toscreen when the likelihood of a 6-month visit islow. Providers can discuss the potential risks, in-cluding opportunity costs, and benefits of screeningwith pregnant women to help reach individualdecisions.

Recommendation SP3: Women who have hadhysterectomies (with no history of ‡ CIN2). Inall settings, screening may be discontinued inwomen who have received a total hysterectomyfor benign causes with no history of cervical dys-plasia or HPV. Women who have received a sub-total hysterectomy (with an intact cervix) shouldcontinue to receive routine screening (Type:

evidence-based; Evidence quality: high; Strengthof recommendation: strong).

Discussion of SP3. The recommendation regard-ing women who have had hysterectomies wasadapted from the 2011 CCO interim recommenda-tionsand the2012ACS/ASCCP/ASCPguidelines24,27

that state that no screening is necessary for womenwho have undergone hysterectomy with cervix re-moval and have had no history of> CIN2 within thepast 20 years. The ACS/ASCCP/ASCP recommenda-tion on screening for vaginal cancer was based onobservational data.

SPECIAL COMMENTARY

What Is the Role of Self-Collection (Only for HPVMolecular Testing)?

For improving coverage of screening, thereis evidence emerging or under way on self-collection (also known as self-sampling). Self-collected (self-sampled) specimensmay be used,with a validated collection device, transport con-ditions, and assay, as an alternative to provider-collected specimens for HPV testing. Triage andfollow-up must be performed according to thesetting and resources available. An ASCO litera-ture search found three systematic reviews and/ormeta-analyses on self-collection. A meta-analysisby Arbyn et al60 found that “[t]he pooled sensitivityofHPV testingonself-sampleswas lower thanHPVtesting on a clinician-taken sample (ratio 0.88[95% CI 0.85 to 0.91] for CIN2 or worse and0.89 [0.83 to 0.96] for CIN3 or worse). In addi-tion, specificity was lower in self-samples versusclinician-taken samples (ratio 0.96 [0.95 to 0.97]for CIN2 or worse and 0.96 [0.93 to 0.99] forCIN3 or worse).”60(p127) There is a significantdifference in the sensitivity of self-sampling versuscervical sampling when a signal amplification testis used, but that difference is minimal or nullwhen a polymerase chain reaction–based test isused. A systematic review and meta-analysis byRacey et al61 found that relative compliance washigher with home-based self-collection HPV DNAtesting kits than with standard clinic-based cytol-ogy. An earlier systematic review by Stewart et al62

found high acceptability by women performingself-collection.

The self-collection protocol, which includes thespecimen collection (ie, device), handling (ie, trans-port buffer and storage conditions), and HPV test,needs to be validated in limited and basic settings ifnotpreviously validated.For example, a temperaturehigher than what is recommended or a differenttransport medium may affect the test performance.

14 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

Asmore evidenceonself-collection is published, theExpert Panel will consider whether to make a formalrecommendation.

What Screening Is Recommended for WomenWhoHave Received HPV Vaccination?

Public health providers should consider changesin cervical cancer screening in the HPV vaccina-tion era in the absence of the two most carcino-genic HPV genotypes. As a consequence of theabsenceofHPV16/18,positive screening testswillbe less predictive of CIN3 and cervical cancer(> CIN3) because the point prevalence of > CIN3is expected to be reduced by> 50%, whereas thetest positivity will be reduced by < 30%.33,63,64

Moreover, HPV 16– and HPV 18–related cervicalcancers occur at an earlier age than those relatedto other HPV genotypes65; therefore, the risk ofcancer is also lowered. Less predictive screeningmeans a poorer benefit-to-harm ratio. Althoughmore data are needed, under the assumption thatwomen were vaccinated before becoming sexu-ally active, in the enhanced and maximal settings,women may receive routine screening with HPVtesting at ages 30, 45, and 60 years. However, ageand frequency cannot be fully addressed until thereare more data.

Screening can be changed in several ways to helprestore good benefit-to-harm ratios in bivalent orquadrivalent HPV-vaccinated populations. First,screening can be started at an older age than iscurrently implemented because the populationrisk of cervical cancer will be lower in HPV-vaccinated (HPV 16 and HPV 18 negative) pop-ulations and cervical cancer caused by other HPVgenotypes happens at a median age approxi-mately 5 years older than does cervical cancercaused by HPV 16 and HPV 18. For example,many screening programs screen unvaccinatedwomen under the age of 25 years, despite the lackof evidence of benefit in this age group,66 andvaccinatedwomen in this agegroupwouldbeevenless likely to benefit given their lower cancer risk.Second, using the principle of equalmanagementfor equal risk,67 longer intervals between screensand/or follow-up in management could be con-sidered. This would allow more benign infectionsand related abnormalities to clear without detec-tion and intervention while shifting the focus topersisting HPV infections that carry a significantriskofprogression.68,69Finally, new,morespecificbiomarkers couldbeused to triage screen-positivewomen to help differentiate between benign hrHPVinfections or related cytologic abnormalities andclinically important hrHPV infections that have

caused, orwill cause,>CIN3.Althoughmuchmoredata are needed before new approaches can beimplemented into routine screening practices,the most promising of these biomarkers includep16/Ki-67 immunocytochemistry,70 E6 oncoproteindetection,71 andHPVviral genomemethylation.72,73

(See New Screening Technologies for backgroundand discussion on biomarkers.)

Although it will be at least a decade before we willconsider the predicted impact of the newest HPVvaccines, in HPV-naıve populations vaccinatedwith the nonavalent HPV vaccine, the questionwill bewhether to screenat all.Most>CIN3will beprevented, especially if there is cross-protectionagainst hrHPV not targeted by nonavalent HPVvaccine. The few remaining CIN3 diagnoses causedby borderline hrHPV or low-risk HPV genotypes mayrarely, ifever,becomeinvasivecancer.TheseHPVge-notypes can still cause significant numbers of minorcytologic74,75 andhistologic76abnormalities thathavelittle clinical importance but would be picked up byscreening. Thus, the harms to the women and costswould be disproportionately high compared with thebenefits towomen.Speculatively,asinglescreeningofmid-adult-agedwomen approximately 35 or 40 yearsof age may be valuable if it leads to the detection ofearly-stage cervical cancer caused by hrHPV typesnotcoveredby thenonavalentHPVvaccineorcausedby borderline hrHPV, and perhaps other female re-productive tract cancers,77 if the lead-time detectionof the latter provides significant health benefit (eg,reduced mortality).

New Screening Technologies

Several new technologies are being investigatedfor all resource setting levels. They need to betested and approved before use in any setting.These include a number of potentially promisingnew biomarkers that might achieve better perfor-mance as a triage for women with hrHPV-positiveresults than cytology and/or HPV genotyping.The most advanced of these next-generation bio-markers with respect to validation and readinessfor introduction into routine practice is p16INK4a

immunocytochemistry (p16 ICC). In a number ofstudies, p16 ICChasdemonstratedhigh sensitivityand specificity that is similar to or better thancytology testing for > CIN2 and > CIN3 amongwomen with hrHPV-positive results.70,78,79 In ad-dition, Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker, has beenincluded with p16 ICC (p16/Ki-67 ICC) as a dualstain to create a morphology-independent test.70

There is also a manual, lateral flow test for thedetection of E6 protein that was developed forlower resource settings. The research use–only

15 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

version of the test targeted HPV 16, HPV 18, andHPV 45 E6 protein, whereas the current commer-cialized version targets HPV 16 andHPV 18. HPV E6protein detectionhasbeenshown tobemore specificthan DNA detection for CIN3 and cervical cancer,even when accounting for restriction to the detectionof the highest risk HPV genotypes.71,80,81 Additionalstudy is needed to confirm this test’s performance.

There are a considerable number of additionalbiomarkers that are being developed. These in-clude, but are not limited to, viral72,73,82,83 andhost82,84-87 methylation, 3q amplification,88-93 andviral integration.94,95 All of these new biomarkerswill need further study and validation before use inany clinical setting, regardless of resource level.

COST AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The secondary prevention of cervical cancer is acost-effective strategy to reduce the incidenceand mortality of cervical cancer. CEAs discussedin this guideline support the introduction of HPVDNA tests in maximal-, enhanced-, and limited-resource settings and the introduction of VIAin basic-resource settings. However, there arespecific implementation issues regarding provid-ing screening and treatment in limited and basicsettings inprimary care, outsideof research studies.

The age group of 30 to 49 years (target age rangerecommended in limited- and basic-resourcessettings) represents approximately 20% to 25%of the entire population of women in a givencountry. LMICs typically have only basic healthsystems, lack resources and facilities, and havelimited or no capacity to manage cancers. Theseformidable barriers to starting a screening pro-gram for this target group can lead to inertia. Onestrategy to overcome these barriers is to considerfurther restriction of the target age for screening.Targeting screening to women in their 30s (eg, 30to 39, 30 to 34, or 35 to 39 years) reduces thenumber of women needing screening, therebyreducing burden on the health care system andcosts, and decreases the number of screen-detected cancers, which typically peak in womenin their 40s and 50s. Even targeting a single-yearage group, for example, 30 or 31 years, wouldenable the development of programs to start andwould help prevent cancer. Whenmore resourcesand capacities become available, the programcan be expanded for catch-up screening in olderpopulations.

Additional strategies to further implementation ofmass screening include buy-in from policymakers,which affects the provision of resources, including

physical infrastructure, prioritizing cancer pre-vention, sponsorship of screening, and qualitycontrol. It is important to address this, at aminimum, by assessing the needs and prefer-ences, follow-up systems, monitoring, evaluation,and partnering with institutions, regions, andcountries with treatment facilities. A publicationentitled “Infrastructure Requirements for HumanPapillomavirus Vaccination and Cervical Can-cer Screening in Sub-Saharan Africa” describesspecific infrastructure elements needed forscreening and cryotherapy programs and canhelp program managers plan for obtaining theseelements.10

GUIDELINE IMPLEMENTATION

ASCO guidelines are developed for implementa-tion across health settings. Barriers to implemen-tation include the need to increase awareness ofthe guideline recommendations among front-linepractitioners and women in general populationsandalso toprovide adequate services in the faceoflimited resources. The guideline Bottom Line Boxwas designed to facilitate implementation of rec-ommendations. This guideline will be distributedwidely, including through many forms of ASCOcommunications and the ASCO Web site.

LIMITATIONS OF RESEARCH

There were limitations in the evidence regardingthe best ages for starting and exiting from screen-ing, screening women with HIV and other types ofimmunosuppression, comparative risks and ben-efits of treatment, and follow-up of women withprecursor lesions. Future research is suggested inthese areas.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In addition to addressing research limitations,future research is needed in other areas (eg,self-collection, biomarkers, needs and prefer-ences of women, low-cost technology, and im-pact of vaccination on screening). Addressingpolicy/health system barriers may include thefollowing:

·Education of medical and public healthcommunities to change practices and in-corporate new technologies

·Participation and sponsorship frompolicymakers

·Partnerships with institutions, regions, orcountries with treatment facilities

·Coordinated volume purchasing and pro-curement of HPV testing

16 jgo.ascopubs.org JGO – Journal of Global Oncology

Dow

nloaded from jgo.ascopubs.org on O

ctober 17, 2016. For personal use only. N

o other uses without perm

ission.C

opyright © 2016 A

merican S

ociety of Clinical O

ncology. All rights reserved.

·Improvement of health information systemsto have better follow-up and treatment ofwomen with positive screening results

·Quality control·Monitoring and evaluation

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Additional information including a Data Sup-plement with additional tables, a MethodologySupplement with information about evidencequality and strength of recommendations, slidesetsandclinical tools,andresourcescanbefoundat