Seasonality and Intensity of Shellfish Harvesting on the North Coast of British Columbia

Transcript of Seasonality and Intensity of Shellfish Harvesting on the North Coast of British Columbia

This article was downloaded by: [North Dakota State University]On: 21 October 2014, At: 18:34Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The Journal of Island and CoastalArchaeologyPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uica20

Seasonality and Intensity of ShellfishHarvesting on the North Coast of BritishColumbiaMeghan Burchell a , Nadine Hallmann b , Andrew Martindale c ,Aubrey Cannon a & Bernd R. Schöne ba Department of Anthropology , McMaster University , Hamilton ,Ontario , Canadab Department of Applied and Analytical Paleontology andINCREMENTS Research Group, Earth System Science ResearchCenter , Institute of Geosciences, University of Mainz , Mainz ,Germanyc Department of Anthropology , University of British Columbia ,Vancouver , British Columbia , CanadaPublished online: 17 Jul 2013.

To cite this article: Meghan Burchell , Nadine Hallmann , Andrew Martindale , Aubrey Cannon& Bernd R. Schöne (2013) Seasonality and Intensity of Shellfish Harvesting on the NorthCoast of British Columbia, The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 8:2, 152-169, DOI:10.1080/15564894.2013.787566

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2013.787566

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Journal of Island & Coastal Archaeology, 8:152–169, 2013Copyright © 2013 Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 1556-4894 print / 1556-1828 onlineDOI: 10.1080/15564894.2013.787566

SPECIAL SECTION: Islands, Coastlines, andStable Isotopes: Advances in Archaeologyand Geochemistry

Seasonality and Intensityof Shellfish Harvestingon the North Coastof British ColumbiaMeghan Burchell,1 Nadine Hallmann,2 Andrew Martindale,3

Aubrey Cannon,1 and Bernd R. Schone2

1Department of Anthropology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada2Department of Applied and Analytical Paleontology and INCREMENTS

Research Group, Earth System Science Research Center, Institute of Geosciences,

University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany3Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver,

British Columbia, Canada

ABSTRACT

Biogeochemical and growth increment analyses show contrasting sea-sonal patterns of butter clam collection and rates of harvest intensitybetween archaeological shell midden sites from the Dundas Islandsarchipelago and the mainland coast in Prince Rupert Harbour, north-ern British Columbia. Growth increment analysis shows more intensiveclam harvest in the Dundas Islands in comparison to the residentialsites in Prince Rupert Harbour. Stable oxygen isotope analysis showsmulti-seasonal collection of clams in the Dundas Islands and a moreseasonally specific emphasis in Prince Rupert Harbour. Comparison ofthese results to those of similar studies in the Namu region on the central

Received 25 September 2012; accepted 13 December 2012.Address correspondence to Meghan Burchell, Department of Anthropology, McMaster University, 1280Main St. W., Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4L9, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]

152

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

coast of British Columbia provides a basis for broader regional under-standing of variation in shellfish harvesting intensity and seasonalityon the Pacific Northwest Coast.

Keywords seasonality, subsistence, settlement, stable isotope analysis, Pacific NorthwestCoast, multi-site/multi-regional analysis

INTRODUCTION

Interpreting seasonal settlement patternsand subsistence in the northern NorthwestCoast region has remained a challenge for ar-chaeologists. There has been some recentemphasis on variation in regional fishingeconomies (Brewster and Martindale 2011;Coupland et al. 2010), but less considera-tion has been given to the influence of envi-ronmental and historical circumstances thatshaped local variation in shellfish use be-tween locations and settlement types. Shell-fishprovideavaluablegeo-cultural archive toexamine patterns of harvest pressure as wellas the season of collection, and by proxy,the season of site occupation. By employ-ing shell growth increment analysis to deter-mine relative rates of harvest pressure (Can-non and Burchell 2009), and stable oxygenisotope analysis (δ18Oshell) to interpret a pre-ciseseasonofcollection(Burchelletal.2012,2013) it is possible to develop a more com-prehensive and fine-grained understandingof how shellfish were integrated into localsubsistence practices than would be possi-ble through previous approaches. This studycompares seasonality and butter clam har-vesting from a wide range of sites, fromdifferent environmental settings, specificallycomparing sites from the Dundas Islands tothe mainland coast in Prince Rupert Har-bour in northern British Columbia, Canada(Figure 1). This comparison allows for theidentification of regional patterns of shell-fish use from two different environmentalsettings, which likely influenced how andwhy shellfish were gathered. Further com-parison of the results from the northern coastto studies from the central coast allows fora broader understanding of regional settle-ment and subsistence, with a specific focuson the role of shellfish.

While the north coast of BritishColumbia has been the subject of archae-

ological investigation for several decades,mainly through single-site excavations (i.e.,Ames 2005; Coupland et al. 2000, 2003; Mac-Donald and Inglis 1981), only in recent yearshas the explicit focus of research shifted toregional, multi-site investigations (Brewsterand Martindale 2011; Coupland 2010; Mar-tindale et al. 2009; McLaren et al. 2011).These research programs have provided crit-ical insight on variability in regional fishingeconomies, but variation in shellfish harvest-ing has been less well documented. Generaldescriptions suggest northern NorthwestCoast subsistence was particularly focusedon fisheries (Ames and Maschner 1999; Mat-son 1992). As Moss has pointed out, there isa lack of attention to shellfish consumptionand harvesting patterns in general descrip-tions of Northwest Coast subsistence (Moss1993; Moss and Erlandson 2010).

Study Area and Subsistence Practices

Located in the traditional territory of theCoast Tsimshian, the Dundas Islands Groupand Prince Rupert Harbour provide a uniquelandscape to assess variability in resourceprocurement and seasonality. The DundasIslands are located 14 km west of Prince Ru-pert Harbour and are composed of five mainislands and multiple smaller islets (Martin-dale et al. 2009). In some parts of the islandarchipelago it is possible during low tide towalk through the intertidal zones to shellmidden sites located on the different islets.Occupation at the Dundas Islands dates backas far as 10,000 years (Martindale et al. 2009;2010; McLaren et al. 2011). It has been de-scribed as a marginal resource area (Ames1998) because it is relatively isolated fromthe mainland coast where the major riversthat supported regional fishing economiesare located. Shell middens from the DundasIslands used in this study exhibit variability inshape, size, and depth with a temporal span

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 153

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Figure 1. Regional map of the north coast of British Columbia showing the locations of the DundasIslands Group and Prince Rupert Harbour (color figure available online).

from 6900 to 1800 years cal. BP (Hallmannet al. 2012). In contrast to sites in PrinceRupert Harbour, sites in the Dundas IslandsGroup are characterized by a low density offish, particularly salmon (Brewster and Mar-tindale 2011).

The Prince Rupert Harbour sites exam-ined in this study include the shell middensites of McNichol Creek (GcTo-6), TremayneBay (GbTo-46), GbTo-77, and Ridley Island(GbTn-19), which date from approximately3380 to 1890 years cal. BP (Patton 2010). Thefull range of shell midden site types on thenorthern coast remains untested, however,with the exception of Ridley Island all thePrince Rupert Harbour sites examined in thisstudy have been identified as villages (Archer2001).

Based on the ethnographic record, fish-ing was identified as the most impor-tant resource procurement activity for the

Tsimshian, and the seasonal availability offish influenced the movement of settlementsand the organization of labor (Halpin andSeguin 1990; Stewart 1975). In the latespring, herring would move to nearshorewaters to spawn, where they would be in-tensively fished and then dried or renderedfor oil (Garfield 1951). The ethnographicrecords of the Tlingit in Alaska also de-scribe people fishing for herring in the sum-mer and fall (Moss et al. 2011). Eulachon,an oil-rich smelt, was identified as an im-portant resource since it was the first fishavailable in the springtime when stores ofdried foodswererunning low(Garfield1951;Miller 1997). Other economically importantfish resources used by the Tsimshian includehalibut and cod, which were available be-tween November and January and were im-portant during times of low food productiv-ity (Garfield 1951; Stewart 1975).

154 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

There is limited ethnographic and ar-chaeological information regarding the roleand significance of shellfish not only withinthe territory of the Tsimshian, but also alongthe entire Pacific coast (Cannon et al. 2008).Historically, the Tsimshian gathered shell-fish during the lowest tides in the wintermonths (Arima and Dewhirst 1990; Moss1993). However, the lack of ethnographicinformation on shellfish harvesting may beattributed to the uneven distribution of at-tention that was paid to male-dominated andmore dramatic subsistence activities suchas fishing and sea mammal hunting (Moss1993). This has likely influenced how shell-fish remains have been treated in archae-ological interpretation, specifically regard-ing pan-coastal ideas that shellfish are alow-priority resource. As further noted byMartindale (2006), the major ethnographicaccounts of Tsimshian pre-contact settle-ment and subsistence practices (Boas 1916;Garfield 1939, 1951) appear to conflate mul-tiple time frames, further emphasizing thequestionability of the ethnographic record.

Seasonality and Shellfishon the North Coast

The proposed seasonal round of theCoastTsimshianhasbeendiscussed inethno-graphic accounts, but not in great detail(Coupland et al. 2010) (see Boas 1916;Drucker 1965; Garfield 1939; Halpin andSeguin 1990; Miller 1997. A generalized “sea-sonal round” indicates that people movedbetween resource procurement locationsthrough the spring and summer, and, bylate autumn, groups of people returned towinter villages with dried salmon and otherpreserved foods (Coupland et. al 2010). Al-though the antiquity of this annual round isunknown, it likely pre-dates the arrival ofthe first Europeans (Martindale 1999). Thelack of detailed ethnographic information onCoast Tsimshian “seasonal rounds” may indi-cate there was more variability in seasonal-settlementpatterns thancouldbeadequatelyobserved and described. Furthermore, thereis little reason to assume this pattern of sea-sonal mobility can be applied uniformly tothe archaeological past. Using ethnography

to understand long-term archaeological his-tories is not always reliable since it does nottake into account change over time in envi-ronmental and/or cultural conditions (Con-neller, 2005; Ford, 1989; Jochim, 1991), and,as discussed in detail by Moss (1993), thereare inherent problems with the nature ofethnographic data on this point. Ethnogra-phy can still contribute valuable informationto understanding the past (see Grier 2007;Martindale 2006; Moss et al. 2011), however,these data should be used with caution whenintegrated into archaeological narratives oflong-term history.

In the Prince Rupert Harbour area, low-resolution analysis of clamshells based onthe formation of “winter growth lines” hasbeen conducted to determine the seasonof site occupation at McNichol Creek andRidley Island (Coupland et al. 1993; May1979). The initial seasonality investigationsindicated that shellfish gathering at RidleyIsland was a year-round activity, with an em-phasis on winter and spring collection (May1979). For the initial 1979 study, a total of97 butter clams (Saxidomus gigantea) andhorse clams (Tresus capax) from bulk sam-ples were selected for seasonality analysisand shell growth patterns were “read” bytwo independent observers. Of the shells an-alyzed, there was an agreement by both ob-servers on the season of death in only 24specimens (24%). Coupland et al.’s (1993)seasonality analysis of shellfish from McNi-chol Creek incorporated butter clams, little-neck clams, and cockles, beginning with atotal sample of 1,128 specimens, which wasreduced to 127 (11% of the original sample)byremovingolder shells, andshells thatweredamaged during preparation. Using Monks’s(1987) method of analysis, season of deathwas determined by the position of the lastwinter growth cessation line or “biocheck”in relation to the previous four years ofgrowth. The study concluded that shellfish-ing occurred throughout the year but with anemphasis during the spring and early sum-mer (Coupland et al. 1993). This analysisrelied on a control sample of live-collectedshellfish from the Fraser Delta region fromthesoutherncoast thatwasthebasisofHam’s(1982) seasonality study. In contrast to these

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 155

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

seasonal patterns, Fitzhugh’s (1995) studyusing stable isotopes found an emphasis onautumn and winter shellfish collection forthe Uyak site on Kodiak Island, Alaska. Al-though this is a different cultural and envi-ronmental region, it provides an interestingfoundation from which to re-examine sea-sonality methods using bivalves.

Recent advances in identifying the sea-son of shellfish collection have shed lighton a variety of factors that make using “win-ter growth lines,” an unreliable method (An-drus 2011; Burchell et al. 2013; Hallmannet al. 2009). For example, a control sampleof bivalves from the Fraser Delta in south-ern British Columbia cannot be applied tothe northern coast since there is a significantdifference in shell growth between the tworegions. Based on the sclerochronology oflive-collected shells from Pender Island onthe south coast (closer to the Fraser Delta)andAlaska(closer toPrinceRupertHarbour),there is approximately a four-to-six monthdifference between the growing seasons.Shells from southern British Columbia cangrow nearly throughout the year, whereasshells from more northern latitudes can stopgrowing for six to seven months (Hallmannet al. 2009). Additionally, different bivalvespecies produce different forms and shapesof growth lines during different periods ofthe year. For example, the growth patternsof butter clams and horse clams are strikinglydifferent (Figure 2).

The present study uses whole butterclam shells and shell fragments with a pre-served ventral margin from 15 sites on the

Dundas Islands (Figure 3) and four sites inPrince Rupert Harbour (Figure 4). Butterclams are an ideal species to examine sea-sonality and subsistence since they are foundin abundance in archaeological sites onthe coasts of Washington, British Columbia,and Alaska (Cannon et al. 2008; Fitzhugh1995; Moss 1993, 2012; Moss and Erland-son 2010; Wessen 1988). A preliminary studyof relative species abundances from foursites in the Dundas Islands (GcTq1, GcTq-5, GcTq-7, GcTr-8) showed butter clams andhorse clams represent between 60 and 80%of the shellfish assemblage based on bothcounts and weights of non-repetitive ele-ments (Cameron et al. 2008). Archaeolog-ical shells from McNichol Creek (GcTo-6),GbTo-77, Tremayne Bay (GcTo-46), and Ri-dley Island (GbTn-19) in Prince Rupert Har-bour were obtained from column samplesarchived at the University of Toronto and theCanadian Museum of Civilization.1

GROWTH INCREMENT ANALYSIS

Following the methods developed by Can-non and Burchell (2009) for interpreting therelative intensity of shellfish harvest, 3,003butter clam shell fragments > 1 cm withan intact ventral margin were analyzed fromthe Dundas Islands. To prepare shells forgrowth increment analysis, specimens werecut along the axis of maximum growth per-pendicular to the growth lines using a low-speed precision saw (Buehler IsoMet 1000)

Figure 2. Thin sections of S. gigantea (left) and T. capax (right) under transmitted light (adaptedfrom Cannon and Burchell 2009). The white lines in both specimens represent growthinterruptions representing either a slowed growth during the winter or an increase infreshwater.

156 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

Figure 3. Map of the Dundas Islands showing the location of sites analyzed in the study.

with a 0.4 mm thick diamond-coated sawblade. Shell portions were ground with dis-tilled water on 320 and 240μm SiC grit paperthenpolishedwith1μmAl2O3 colloidal solu-tion on a billiard cloth using a high-speed pol-isher (BuehlerEcomet3).Aftereachgrindingandpolishingsteptheshellswerecleanedviaultrasonic bath to remove any adhering pow-der and allowed to dry. Polished shell frag-ments were examined with a Nikon SMZ800digital zoom microscope under 40 × mag-nification to examine the pattern of growthlines and determine if the shell was in a ma-ture or senile stage of growth. A record waskept of the growth patterns, and matched be-tween shell fragments to avoid analyzing thesame specimen twice.

Age categories of mature and senilegrowth can easily be distinguished by ex-amining the distribution of growth bands atthe ventral margin of the shell. Older shellshave a distinct growth pattern where darkerlines are tightly clustered at the ventral mar-gin due to slowing rates of shell carbon-ate deposition. In contrast, shells in a ma-ture stage of growth have even and broadlyspaced growth lines because of the highergrowth rates (Claassen 1998). Any shell thatcould not be readily identified as either “ma-ture” or “senile” was classified as “unknown”(Figure 5). Sites with a higher proportion ofshells in a mature stage of growth imply amore intensive harvesting rate than thosewith higher proportions of senile shells,

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 157

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Figure 4. Map of Prince Rupert Harbour showing the location of sites analyzed in the study (colorfigure available online).

since shellfish are being harvested beforethey reach the stage of senile growth. Tocompare the results of the Dundas Islandsto those from the mainland coast, a totalof 690 butter clam fragments was analyzedfrom the four sites in Prince Rupert Harbour(Table 1).

Growth patterns in butter clams fromthe northern coast of British Columbia canbe compared to shells from the central coastsince they have similar growth rates; shellsfrom both regions can stop growing for upto six months (Burchell et al. 2012; Hallmannet al. 2009). Shells from the southern coastgrow faster, reaching senile growth betweenfive and six years, whereas shells from the

central and northern coasts reach senilitybetween eight and ten years (Gillespie andBourne 2005a, 2005b; Gillespie et al. 2004).Intertidal zones where shellfish are not har-vested on a regular basis are generally dom-inated by shells in a senile stage of growth.All live-specimens collected from the Dun-das Islands that were used as a proxy to inter-pret the stable oxygen isotope values wereolder than eight ontogenetic years, and hadclearly developed a senile growth pattern.Table5 inCannonandBurchell (2009)showsthe distribution of a sample of live-collectedshells in areas monitored by Fisheries andOceans Canada on the central coast of BritishColumbia.

Figure 5. Examples of mature (left) and senile (right) growth in S. gigantea.

158 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

Table 1. Total number of shells used and their associated age categories from the DundasIslands and Prince Rupert Harbor.

Site Senile Mature Uncertain Site total

Dundas Islands

GdTq-1 10 22 6 38

GcTr-5 58 88 48 194

GcTq-5 211 324 55 590

GcTq-7 44 229 41 314

GcTr-10 45 67 15 127

GcTq-13 10 20 2 32

GcTr-8 223 319 38 580

GcTr-9 20 49 9 78

GcTq-1 51 70 19 140

GcTq-6 143 144 28 315

GcTq-9 50 107 14 171

GcTq-4 52 102 26 180

GcTr-6 7 5 6 18

GdTq-3 65 70 18 153

GcTq-11 20 45 8 73

Regional total 1009 1661 333 3003

Prince Rupert Harbour

McNichol Creek, GcTo-6 70 88 8 166

Tremayne Bay, GbTo-46 57 91 5 153

Dodge Cove, GbTo-77 114 45 4 163

Ridley Island, GbTn-19 116 69 23 208

Regional total 357 293 40 690

The Dundas Islands growth incrementanalysis reveals that butter clams were col-lected intensively since there are a greaterproportion of shells in a mature stage ofgrowth at 14 of the 15 sites (Figure 6). Whenthe results from all the sites are combined,55% of the shells were in a mature stage ofgrowth, and 34% were in a senile stage ofgrowth. A total of 11% of the shells were clas-sifiedas“unknown;”however, it is importantto note that this classification was more of-ten than not the result of annual growth linesnot being clearly visible under reflected lightand magnification.

The pattern of harvesting observed atthe Dundas Islands differs from the overallpattern of butter clam collection at Prince

Rupert Harbour, which shows less inten-sive collection (Figure 6). Overall, 51% ofthe butter clams in Prince Rupert Harbourwere in the senile stage of growth, and 42%were in a mature stage of growth. Only7% of the shell samples from Prince Ru-pert were classified as “unknown.” Althoughthe overall pattern of harvest is less inten-sive on the mainland coast, there was vari-ability observed between sites. Butter clamsfrom McNichol Creek and Tremayne Bayhave higher proportions of shells in maturestages of growth (53% and 59% mature, re-spectively), and GbTo-77 and Ridley Islandhave higher proportions of shells in a se-nile stage of growth (70% and 65% senile,respectively).

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 159

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Figure 6. Percent of butter clam shell age categories determined by growth increment analysis from4 sites in Prince Rupert Harbour and 15 sites in the Dundas Islands (color figure availableonline).

STABLE OXYGEN ISOTOPE ANALYSIS

Butter clam shells from five sites from theDundas Islands (GcTq-5, GcTq-6, GcTr-6,GdTq-1, and GdTq-3) were previouslyselected for radiocarbon dating and stableisotope analysis to examine trends inpaleoclimate and to develop a preliminaryassessment of the season of butter clamcollection (Hallmann et al. 2012). Shells fromtwo additional Dundas Islands sites (GcTq-9and GcTq-13) were added to expand theanalysis of seasonal butter clam harvest. Bothadditional sites exhibited higher densities ofherring and eulachon suggesting a possiblespring occupation (Brewster and Martindale2011). Since both species of fish couldbe stored, it is difficult to assess seasonaloccupation based on their presence alone.

Incorporating the seasonality of butter clamcollection makes it possible to refine this in-terpretation. A total of 1,333 discrete isotopesamples from 42 individual shell samplesfrom the Dundas Islands were analyzed todetermine the season of shellfish collection.Ten butter clam shells with 100 discreteisotope samples from McNichol Creek (n= 5) and Ridley Island (n = 5) were alsoanalyzed for seasonality. While the numberof shell samples from Prince Rupert Harbouris small, it provides a basis from which tore-examine the previous seasonality inter-pretations that relied on lower-resolutionmethods. The results are sufficient to suggesta new understanding of patterns of shellfishharvesting and site occupation.

To determine δ18Oshell, carbonate pow-der was obtained by hand micromilling at

160 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

the ventral margin followed by microdrillingin the faster growing portions from the outershell layer of polished cross sections. Mi-cromilling was applied to attain a higherresolution for determining seasonality bymoving in ∼100 μm consecutive steps be-ginning at the ventral margin, contouring thegrowth lines using a 1 mm diamond-coatedcylindrical drill bit (Komet/Gebr. BrasselerGmbH & Co. KG model no. 835 104 010)(Figure 7). Micromilling allows for an unin-terrupted record to be obtained, and mini-mizes the effects of time-averaging, whichis the mixing of different time periods ofshell growth (Goodwin et al. 2004). Afterthe ventral margin was milled, the fastergrowing portions of the shell were micro-drilled using a 300 μm conical drill bit(Komet/Gebr. Brasseler GmbH & Co. KGmodel no. H52 104 003). The distance be-tween the center-to-center of the drill sam-

ples varied between 400 and 600 μm. Sinceshell samples varied in both the size ofthe fragment and ontogenetic age, eachpolished shell was examined under 40 ×magnification to observe the microgrowthstructures, and a specific sampling strat-egy combining micromilling and micro-drilling was selected to attain the highestseasonality resolution possible by selectingthe appropriate spacing of sample pointsto capture the last few months of shellgrowth.

Isotope samples were analyzed by reac-tion with phosphoric acid in a Gas Bench IIcoupled to a Thermo Finnigan MAT 253 con-tinuous flow-isotope ratio mass spectrome-ter. Isotope data were calibrated against NBS-19 (δ18O =−1.95�). The δ18Oshell values areexpressed relative to the international VPDB(Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite) standard and aregiven as per mil (�).

Figure 7. Sampling strategy for micromilling at the ventral margin and microdrilling shell carbon-ate to identify the season of shellfish collection.

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 161

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Stable oxygen isotope studies of but-ter clam demonstrated that this speciessecretes its shell inclose isotopicequilibriumwith ambient seawater (Burchell et al. 2012;Gillikin et al. 2005; Hallmann et al. 2009,2011, 2012).no When the sequence of iso-tope data is sufficiently long to cover oneor more years of shell growth, a sinusoidalcurve is produced when the data are plotted,reflecting seasonal changes in both the wa-ter temperature and salinity (Figure 8). Sta-ble oxygen isotope ratios from the ventralmargin of the shell with more negative oxy-gen isotope ratios are interpreted as “sum-mer,” and the more positive are interpretedas“winter.”Theflanksof thesinusoidalcurvewhere it is either decreasing or increasingas a function of distance from the ventralmargin represent autumn and spring respec-tively when the data are plotted inversely(Burchell et al. 2012).

It should be noted that seasonal freshwa-ter discharges have more negative δ18Owater

value, and increase the overall δ18Oshell

amplitude; therefore, the overall amplitude

of the isotope data is also considered in asso-ciation with microgrowth line formation andthe direction of the slope of the curve (seeFigure 6 in Burchell et al. 2013). The δ18Oshell

ventral margin values from the Dundas Is-lands ranged from to 0.29� to −4.36�, andfrom −1.11� to −4.46� in Prince RupertHarbour. The amplitude of δ18Oshell ventralmargin values in Prince Rupert is 3.35� and4.65� for the Dundas Islands. Prince Ru-pert Harbour is located between the mouthsof two major rivers, the Skeena and theNass, therefore it is likely that shells fromthis area are more prone to freshwater in-fluxes, specifically the increase in freshwa-ter from snow melting during the spring andearly summer. This is observed in severalspecimens where shells identified as “springcollected” have the most negative δ18Oshell

at the ventral margin, for example samplesGcTq-9–5 (−4.23�), GcTo-6–1 (−3.02�),and GbTn-19–5 (−3.30�). Since a 1� shiftin δ18O equates to approximately a 4.42oCchange in ambient seawater using the Bohmet al. (2000) paleothermometry equation, an

Figure 8. Stable oxygen isotope profile of an autumn collected shell from site GdTq-3, Dundas Is-lands. The δ18O values are plotted inversely, with the most positive values associated withwinter at the bottom of the Y-axis and the more negative values associated with warmertemperatures at the top of the Y-axis. The greater numbers of data near the ventral marginresults from higher sampling resolution (milling vs. drilling).

162 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

amplitude of 5.57� equates to a tempera-ture range of almost 24oC, exceeding the ob-served sea surface temperatures for the re-gion of 2.5 oC to 17oC by approximately 10oC(Hallmann et al. 2012). However, when themicrogrowth lines are examined in relationto the most negative isotope values, they cor-respond to shell collection in the early springas determined by the number of daily growthincrementscountedfromthelastgrowthces-sation from the winter.

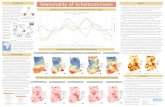

At the Dundas Islands the overall season-ality results show that butter clam collectionoccurred throughout the year at almost allof the sites investigated, but with a strongeremphasis on harvesting during the winter(Table 2; Figure 9). Four of the seven sitesinvestigated were dominated by winter har-vesting. The site GcTq-6 was the only siteinvestigated that had a stronger emphasis onspring collection. Autumn and summer arerepresented at all the sites, but to a slightlylesser extent. The sites (GcTq-9, GcTq-13)had the highest density of herring and eu-lachon, which suggests a pattern consistentwith what could be described as winter vil-lage occupation or multi-seasonal residentialoccupation. These sites show shellfish col-lection occurred predominantly in the win-ter, but also in the spring and autumn.

On the mainland coast in Prince RupertHarbour, butter clam collection was identi-fied during the autumn and spring months atRidley Island and McNichol Creek (Table 3).Although the sample sizes for the sites aresmall (n = 5 per site) in comparison to theoriginal seasonality studies (i.e., Couplandet al. 1993; May 1979), the increase in pre-cision has presented a new interpretationfor the seasons of butter clam harvesting. AtMcNichol Creek, three shells were collectedin the autumn and two were collected in thespring. This differs from Coupland et al.’s(1993) results, which showed an emphasison spring and early summer. Similarly, theRidley Island results showed four shells col-lected in the spring and one collected inthe autumn, contrasting with May’s (1979)conclusion that winter and spring werethe preferred seasons of collection. Sincethe sample size for Prince Rupert Harbouris small, results of the current study are

not sufficient to demonstrate conclusivelyany particular seasonal emphasis, but theyclearly contrast with the Dundas Islands pat-tern, and suggest a possible emphasis onspring and autumn collection in Prince Ru-pert Harbour. The implication would be thatshellfish was collected in the spring whenstored winter food became depleted and inthe fall when people were preparing shell-fish meat to be dried and stored for thewinter.

REGIONAL VARIABILITY IN SHELLFISHHARVESTING

The intensity of shellfish harvesting at theDundas Islands can be interpreted by exam-ining historical and environmental contextsof the region. There is a Northwest Coastprecedent for the transportation of large vol-umes of dried fish up to 100 km from wherethey were captured (Ames 1994), and Oberg(1973) notes that shellfish meat was pro-cessed on the islands and traded to loca-tions inthemainland.Therefore it isplausiblethat shellfish was harvested at the Dundas Is-lands and transported back to Prince RupertHarbour. The intertidal zones at the DundasIslands provide ample zones of shellfish pro-ductivity, however, the potential transporta-tion of shellfish meat is almost impossibleto evaluate. It is likely the inhabitants of theDundas Islands were more reliant on shell-fish as a staple food source, and that peopleliving on the mainland coast did not needto harvest shellfish as intensively since therewere other locally abundant resources fromwhich to choose. Shellfish in both areas mayhave provided crucial nutrition in the springand winter months prior to the spawning ofeulachon and herring.

Shellfish are a poor source of calo-ries when compared to plant and terrestrialand/or other marine animal foods (Erland-son 1988), and it has been argued that theinvestment required to obtain shellfish is notworth the economic return (Osborn 1977).However, shellfish can be gathered in abun-dance fairly quickly, and provide enoughdaily protein to sustain an individual (Erland-son 1988). The evidence suggests shellfish

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 163

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Table 2. Seasonality and radiocarbon dates from butter clams from the Dundas Islands.Martindale et al. (2009) present comprehensive details on all radiometric datesfrom the Dundas Islands.

Auger depth δ18O (‰) at Years cal.

Site Sample ID (cm) DBS ventral margin Season BP (2-sigma)

GcTq-9 GcTq-9–1 80–100 0.08 Winter

GcTq-9–2 80–100 −2.73 Spring

GcTq-9–3 120–140 −1.40 Autumn

GcTq-9–4 120–150 −0.17 Winter

GcTq-9–5 140–169 −4.23 Spring

GcTq-13 GcTq-13–1 80–100 −0.07 Winter

GcTq-13–2 80–100 −2.07 Autumn

GcTq-13–3 100–120 −0.24 Winter

GcTq-13–4 120–140 −0.81 Winter

GcTq-13–5 120–140 −3.55 Spring

GcTq-5 GcTq-5–1 60–80 0.21 Winter 1852–2346

GcTq-5–2 60–80 −1.10 Spring

GcTq-5–3 220–240 −1.45 Spring 2315–2797

GcTq-5–4 240–260 −3.30 Summer 2340–2855

GcTq-5–5 260–280 −4.36 Summer 2369–2929

GcTq-5–6 440–460 −1.41 Autumn 2745–3529

GcTq-5–7 440–460 −2.35 Autumn

GcTq-6 GcTq-6–1 60–80 −0.62 Autumn 1337–1824

GcTq-6–2 60–80 −0.99 Spring

GcTq-6–3 100–120 −2.94 Summer 1391–1182

GcTq-6–4 200–220 −1.14 Spring 1438–1952

GcTq-6–5 240–260 −1.58 Spring

GcTq-6–6 240–260 −2.18 Summer 1379–1868

GdTq-1 GdTq-1–1 84–112 −2.81 Summer

GdTq-1–2 143–168 −0.04 Winter

GdTq-1–3 143–160 −0.03 Winter 1513–2025

GdTq-1–4 168–196 −3.72 Summer 1921–2479

GdTq-1–5 224–245 0.29 Winter 1596–2125

GcTr-6 GcTr-6–1 110–115 0.14 Winter 6489–7361

GcTr-6–2 112–140 0.18 Winter

GcTr-6–3 140–168 0.06 Winter

GcTr-6–4 170–175 −1.39 Autumn 6968–7438

GcTr-6–5 196–224 −0.83 Spring

GdTq-3 GdTq-3–1 140–168 −2.33 Spring 5382–5862

GdTq-3–2 140–168 −0.71 Winter

GdTq-3–3 252–280 −0.55 Winter 5657–6167

GdTq-3–4 252–280 −0.29 Winter

GdTq-3–5 282–308 −2.61 Summer 6315–6813

GdTq-3–6 336–364 0.00 Autumn 6428–6949

GdTq-3–7 364–392 −1.50 Autumn

GdTq-3–8 364–392 −2.12 Summer 6497–7047

164 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

Figure 9. Results of seasonality analysis from seven sites in the Dundas Islands based on shell oxygenisotopes and micro-increment analysis (color figure available online).

were collected in the Dundas Islands at anintensive rate throughout the year, indicat-ing they were important and necessary com-ponents of the diet.

In contrast to the pattern of year-roundshellfish harvesting in the Dundas Islands,thealbeit limitedseasonalitydata fromPrinceRupert Harbour suggests an emphasis onclam collection during the autumn and

spring months, a pattern which is consistentwith the seasonal pattern observed at long-term residential sites on the central coast(Burchell et al. 2013). If the sample size wasincreased, we expect that the results wouldshowthatbutterclamswerecollectedtosup-plement the diet throughout the year, butthe emphasis was on harvest in autumn andspring.

Table 3. Seasonality of butter clam shells from McNichol Creek (GcTo-6) and Ridley Island(GbTn-19), Prince Rupert Harbour.

Location/depth δ18O (‰) at

Sample ID Unit (cm DBS) ventral margin Season

McNichol Creek

GcTo-6–1 21N, 10W Layer C, Level 2 −3.02 Autumn

GcTo-6–2 21N, 10W Layer C, Level 9 −2.44 Autumn

GcTo-6–3 21N, 10W Layer C, Level 16 −3.72 Spring

GcTo-6–4 21N, 10W Layer C, Level 19 −1.89 Autumn

GcTo-6–5 21N, 10W Layer C, Level 14 −1.54 Spring

Ridley Island

GbTn-19–1 1–2S, 10–11E 140–150 −2.37 Spring

GbTn-19–2 1–2S, 10–11E 160–170 −1.11 Autumn

GbTn-19–3 5–7S, 0–1W 80–90 −4.46 Spring

GbTn-19–4 5–7S, 0–1W 110–120 −2.36 Spring

GbTn-19–5 6–7S, 11–12W 180–190 −3.30 Spring

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 165

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Long-term residential sites on the centralcoast, such as Namu (ElSx-1) and Kisameet(ElSx-3), showaclearemphasisonspringandautumn harvesting (Burchell et al. 2013) anda less intensive rate of collection when com-pared with specialized resource camps in thevicinity (Cannon and Burchell 2009). Loca-tions identified as places for the specific pur-pose of shellfish gathering show an empha-sis on summer, autumn, and winter, whereassmallersitesshowyear-roundcollection.Theintensity of butter clam harvesting on thecentral coast is comparable to Prince RupertHarbour, but it is different than the more in-tensive harvesting observed in the Dundas Is-lands. The growth increment analysis of 772shells from nine sites on the central coast byCannon and Burchell (2009) revealed thatoverall 51% (390/772) of shells were col-lected in a mature stage of growth and 45%(351/772) in a senile stage of growth, withthe remaining shells classified as unknown(4%) Specific patterns of shellfish harvestingare observed between longer term residen-tial sites and short-term occupation sites, es-pecially those with a specific emphasis ongathering shellfish. For example, only 38%(70/185) of the shells from the village site ofNamu were in the mature stage of growthand 62% (115/185) were senile. In contrast,the shell midden site at Kiltik Cove, ElTa-25,which was identified as a small camp occa-sionally used specifically for harvesting shell-fish showed 67% (174/261) mature-growthshells and 30% (79/261) senile-growth shells,with eight shells classified as “unknown.” Ingeneral, on the central coast, the intensity ofshellfish collection is lower at long-term resi-dential sites thanat smaller sites representingmore ephemeral occupations (Cannon andBurchell 2009).

The Prince Rupert Harbour results showthere is variation in the intensity of harvest,even at village sites. The lower harvest in-tensity at GbTo-77 and the Ridley Island siteis similar to the pattern observed at long-term residential sites and villages on the cen-tral coast (Cannon and Burchell 2009). Incontrast, the more intensive harvest at thelarger village sites of McNichol Creek andTremayne Bay is similar to the patterns ob-served at smaller campsites or specialized

resource procurement camps. It is possiblethat shellfish were integrated differently intothe subsistence economies of the Prince Ru-pert Harbour sites based on currently un-known historical or environmental contin-gencies. Much more information on shellfishharvest at a wider range of sites, more de-tailed understanding of site occupations, andestimates of the sizes of resident populationsare needed to thoroughly assess and evaluatethe nature and role of shellfish collection inPrince Rupert Harbour.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the growth increment and sta-bleoxygen isotopeanalyseshave shownvari-ability in the season of butter clam collec-tion not only between regions, but also be-tween sites within a region. This variability islikely attributable to the environmental andhistorical circumstances that structure theneed (or desire) to harvest butter clams. Onthe Dundas Islands, the seasonality patternand the rates of harvest intensity suggest thatshellfish were a crucial resource. Shellfishwere intensively collected year round over a5,000-year period. In Prince Rupert Harbour,shellfish were harvested at variable rates be-tween sites, but overall were less intensivelyharvested than in the Dundas Islands. This islikely attributable to access to a greater abun-dance of salmon (Coupland et al. 2010).

By comparing the results of the northcoast to the central coast, differences in re-gional shellfish harvesting practices have be-gun to emerge. Although the sample size ofshells analyzed for seasonality from PrinceRupert Harbour is small, it has provided amore precise estimate of shellfish harvestingpatterns, and one that stands in contrast toearlier, lower resolution studies. The com-bination of studies from the north and cen-tral coasts demonstrates that seasonal shell-fishing strategies are contingent on multiplefactors, including environment and variablepatterns of site use over time. At this point,it is not possible to find a simple correlationbetween the seasons of collection and har-vest intensity since the factors that influence

166 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

subsistence and settlement are likely numer-ous and potentially changed over time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this research was providedby the Social Science Research Council ofCanada (SSHRC) in the form of a schol-arship to Meghan Burchell and a researchgrant (410–2004–0618) toAndrewMartin-dale. Funding was also provided by the Ger-man Research Foundation (DFG) to BerndR. Schone: SCHO 793/3. The analytical fa-cilities at the McMaster University Fish-eries Archaeology Research Centre weredeveloped with a Canada Foundation forInnovation grant (CFI) to Dr. Aubrey Can-non. Dr. Katherine Patton and Dr. GaryCoupland kindly provided materials fromPrince Rupert Harbour, and Stacy GirlingChristie and Kevin Jenkins facilitated theloan of shell materials from the CanadianMuseum of Civilization. Neil Bourne fromFisheries and Oceans Canada gave valu-able insight into shell growth rates andprovided hard-to-find references on the in-tertidal clam surveys of British Columbia.Dr. Henry P. Schwarcz and Katherine Cookprovided helpful editorial comments andMiranda Brunton is thanked for preparingand processing shells from several of thesites in the Dundas Islands. Three anony-mous reviewers are thanked for their in-sightful comments and critique.

END NOTE

1. Additional shell growth increment data fromfour sites from the Dundas Islands (GcTq-1,GcTq-5, GcTq-7, GcTr-8) were incorporatedfrom Brunton and Burchell (2008).

REFERENCES

Ames,K.M.1994.TheNorthwestCoast:Complexhunter-gatherers, ecology and social evolution.Annual Review of Anthropology 23:209–229.

Ames, K. M. 1998. Economic prehistory of theNorthern British Columbia Coast. Arctic An-thropology 35:68–87.

Ames, K. M. 2005. The North Coast PrehistoryProject Excavations in Prince Rupert Har-bour, British Columbia: The Artifacts. Oxford:BAR International Series 1342.

Ames, K. M. and H. D. G. Maschner. 1999. Peoplesof theNorthwestCoast:TheirArchaeologyandPrehistory. London: Thames and Hudson.

Andrus, C. F. T. 2011. Shell midden sclerochornol-ogy. Quaternary Science Reviews 30:2892–2905.

Archer, D. J. W. 2001. Village patterns andthe emergence of ranked society in thePrince Rupert Area. In Perspectives on North-ern Northwest Coast Prehistory (J. Cybul-ski, ed.):203–222. Archaeological Survey ofCanada Paper 160. Hull: Canadian Museum ofCivilization.

Arima, E. and J. Dewhirst. 1990. Nootkans of Van-couver Island. In Handbook of North Ameri-can Indians, Vol. 7: Northwest Coast (W. Sut-tles, ed.):391–441. Washington, DC: Smithso-nian Institution.

Boas, F. 1916. Tsimshian mythology. In 31st An-nual Report of the Bureau of American Eth-nology for the Years 1909–1910: 22–1037.Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnol-ogy.

Bohm, F., M. M. Joachimski, W.-C. Dullo, A. Eisen-hauer, H. Lehnert, J. Retiner, and G. Worheide.2000. Oxygen isotope fractionation in marinearagonite of coralline sponges. Geochimica etCosmochimica Acta 64:1695–1703.

Brewster, N. and A. Martindale. 2011. An archaeo-logical history of Holocene fish use in the Dun-das Islands Group, British Columbia. In TheArchaeology of North Pacific Fisheries (M.Moss and A. Cannon, eds.): 247–264. Fairbanks:University of Alaska Press.

Brunton, M. and M. Burchell. 2008. Shellfish har-vesting patterns at the Dundas Islands Group.Paper presented at the 41st Annual Meeting ofthe Canadian Archaeological Association, Pe-terborough, Ontario, May 8–11.

Burchell, M., A. Cannon, N. Hallmann, H. P.Schwarcz, and B. R. Schone. 2012. Refiningestimates for the season of shellfish collec-tion on the Pacific Northwest Coast: Apply-ing high-resolution oxygen isotope analysis andsclerochronology. Archaeometry 55:258–276.doi:10.1111/j.1475–4754.2012.00684.

Burchell, M., A. Cannon, N. Hallmann, H. P.Schwarcz, and B. R. Schone. 2013. Inter-sitevariability in the season of shellfish collectionon the central coast of British Columbia. Jour-nal of Archaeological Science 40:626–636.

Cameron, K., M. Burchell, and T. J. Orchard.2008. Coveted clams and back-up barnacles?

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 167

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Meghan Burchell et al.

Species identification of shellfish from theDundas Islands Group, British Columbia. Pa-per presented at the 41st Annual Meeting ofthe Canadian Archaeological Association, Pe-terborough, Ontario, May 8–11.

Cannon, A. and M. Burchell. 2009. Clam growth-stage profiles as a measure of harvest intensityand resource management on the central coastof British Columbia. Journal of ArchaeologicalScience 36:1050–1060.

Cannon, A., M. Burchell, and R. Bathurst. 2008.Trends and strategies in shellfish gathering onthe Pacific Northwest Coast of North America.In Early Human Impacts on Megamolluscs (A.Antczak and R. Cipriani, eds.):7–22. Oxford:BAR International Series 1865.

Claassen, C. 1998. Shells. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Conneller, J. 2005. Moving beyond sites:Mesolithic technology in the landscape. InMesolithic Studies at the Beginning of theTwenty-First Century (N. J. Miner and P. Wood-man, eds.):42–55. Oxford: Oxbow.

Coupland, G., C. Bissel, and S. King. 1993. Pre-historic subsistence and seasonality at PrinceRupert Harbour: Evidence from the McNicholCreek Site. Canadian Journal of Archaeology17:59–73.

Coupland, G., R. C. Colten, and R. Case. 2003.Preliminary analysis of socioeconomic orga-nization at the McNichol Creek site, BritishColumbia. In Emerging from the Mist: Studiesin Northwest Coast Culture History (R. G. Mat-son, G. Coupland, and Q. Mackie, eds.):152–169. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Coupland, G., K. Stewart, and T. J. Hall. 2000. Ar-chaeological Investigations in the Prince Ru-pert Area in 1999 and 2000: The Differenti-ated Regional Economy at Prehistoric PrinceRupert. Victoria: Archaeology Branch, BritishColumbia Ministry of Sustainable Resource De-velopment.

Coupland, G., K. Stewart, and K. Patton. 2010.Do you never get tired of salmon? Evidence forextreme salmon specialization at Prince RupertHarbour, British Columbia. Journal of Anthro-pological Archaeology 29:189–207.

Drucker, P. 1965. Cultures of the North PacificCoast. San Francisco: Chandler.

Erlandson, J. M. 1988. The role of shellfishin coastal economies: A protein perspective.American Antiquity 53:102–109.

Fitzhugh, B. 1995. Clams and the Kachemak: Sea-sonal shellfish use on Kodiak Island, Alaska(1200–800 B.P.). In Research in Economic An-thropology, Vol. 16 (B. L. Isaac, ed.):129–176.Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Ford, P. 1989. Archaeological and ethnographiccorrelates of seasonality: Problems and solu-tions on the Northwest Coast. Canadian Jour-nal of Archaeology 13:133–150.

Garfield, V. E. 1939. Tsimshian Clan and Society.Seattle: University of Washington Publicationsin Anthropology.

Garfield, V. E. 1951. The Tsimshian and theirneighbors. In The Tsimshian Indians andTheir Arts. (V. Garfield and P. Wingert, eds.):3–70. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

Gillespie, G. E. and N. F. Bourne. 2005a. Ex-ploratory intertidal bivalve surveys in BritishColumbia—2002. Canadian Manuscripts Re-port on Fisheries and Aquatic Science 2733.

Gillespie, G. E. and N. F. Bourne. 2005b. Ex-ploratory intertidal bivalve surveys in BritishColumbia—2004. Canadian Manuscripts Re-port on Fisheries and Aquatic Science 2734.

Gillespie, G. E., N. F. Bourne, and B. Rusch.2004. Exploratory intertidal bivalve surveys inBritish Columbia—2000 and 2001. CanadianManuscripts Report on Fisheries and AquaticScience 2861.

Gillikin, D. P., F. De Ridder, H. Ulens, M. Elskens,E. Keppens, W. Baeyens, and F. Dehairs. 2005.Assessing the reproducibility and reliability ofestuarinebivalveshells (Saxidomusgiganteus)for sea surface temperature reconstruction:Implications for paleoclimate studies. Palaeo-geography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecol-ogy 228:70–85.

Goodwin, D. H., K. W. Flessa, M. A. Tellez-Duarte,D. L. Dettmann, B. R. Schone, and G. A. Avila-Serrano. 2004. Detecting time-averaging andspatial mixing using oxygen isotope variation:A case study. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclima-tology, Palaeoecology 205:1–12

Grier, C. 2007. Consuming the recent for con-structing the Ancient: The role of ethnographyin Coast Salish archaeological interpretation. InBe Of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish(B. G. Miller, ed.):284–397. Vancouver: UBCPress.

Hallmann, N., M. Burchell, B. R. Schone, N. Brew-ster, and A. Martindale. 2012. Holocene cli-mate and archaeological seasonality of shell-fish at the Dundas Islands Group, northernBritish Columbia—A bivalve sclerochronolog-ical approach. Palaeogeography, Palaeocli-matology, Palaeoecology 373:163–172. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.12.019.

Hallmann, N., M. Burchell, B. R. Schone,and D. Maxwell. 2009. High-resolution scle-rochronological analysis of the bivalve mol-lusk Saxidomus gigantea from Alaska andBritish Columbia: Techniques for revealing

168 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 2 • 2013

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4

Shellfish Harvesting in Northern British Columbia

environmental archives and archaeological sea-sonality. Journal of Archaeological Science36:2353–2364.

Hallmann, N., B. R. Schone, G. V. Irvine,M. Burchell, E. D. Cokelet, and M. Hilton.2011. An improved understanding of theAlaska Coastal Current: The application ofa bivalve growth-temperature model to re-construct freshwater-influenced paleoenviron-ments. Palaios 26:346–363.

Halpin, M. and M. Seguin. 1990. Tsimshian peo-ples: Southern Tsimshian, Coast Tsimshian,Nishga and Gitksan. In Handbook of NorthAmerican Indians, Vol. 7: Northwest Coast(W. Suttles, ed.):267–284. Washington, DC:Smithsonian Institution.

Ham, L. 1982. Seasonality, Shell Midden Lay-ers, and Coast Salish Subsistence Activitiesat the Crescent Beach Site, DgGr-1. Ph.D.Dissertation. Vancouver: University of BritishColumbia.

Jochim, M. A. 1991. Archaeology as long-term ethnography. American Anthropologist93:308–321.

MacDonald, G. F. and R. I. Inglis (eds.). 1981. Anoverview of the north coast prehistory project(1966–1980). BC Studies 48:37–63.

Martindale, A. 1999. The River of Mist: CulturalChange in the Tsimshian Past. Ph.D. Disserta-tion. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Martindale, A. 2006. Methodological issues in theuse of Tsimshian oral Traditions (Adawx) in Ar-chaeology. Canadian Journal of Archaeology30:158–192.

Martindale, A., B. Letham, N. Brewster, andA. Ruggles. 2010. The Dundas IslandsProject. Victoria: Archaeology Branch, BritishColumbia Ministry of Sustainable ResourceDevelopment.

Martindale, A., B. Letham, D. McLaren, D. Archer,M.Burchell, andB.R. Schone.2009.Mappingofsubsurface shell midden components throughpercussion coring: Examples from the Dun-das Islands. Journal of Archaeological Science36:1565–1575.

Matson, R. G. 1992. The evolution of NorthwestCoast subsistence. In Long-Term SubsistenceChange in Prehistoric North America, Vol.Supplement 6 (D. R. Croes, R. A. Hawkins, andB. L. Isaac, eds.):367–430. Greenwich, CT: JAIPress.

May, J. 1979. Archaeological Investigations atGbTn-19, Ridley Island, a Shell Midden in thePrince Rupert Area. Manuscript No. 1530. Ot-tawa: Archaeological Survey of Canada.

McLaren, D., A. Martindale, Q. Mackie, and D.Fedje.2011.Relict shorelinesandshellmiddensof the Dundas Islands Archipelago. CanadianJournal of Archaeology 35:86–116.

Miller, J. 1997. Tsimshian Culture: A LightThrough the Ages. Lincoln: University of Ne-braska Press.

Monks, G. 1987. Prey as bait: The Deep Bayexample. Canadian Journal of Archaeology11:119–142.

Moss, M. L. 1993. Shellfish, gender and sta-tus on the Northwest Coast: Reconciling ar-chaeological, ethnographic and ethnohistori-cal records of the Tlingit. American Anthro-pologist 95:631–652.

Moss, M. L. 2012. Understanding variability inNorthwest Coast faunal assemblages: Beyondeconomic intensification and cultural complex-ity. Journalof IslandandCoastalArchaeology1:1–22.

Moss, M. L., V. Buttler, and J. T. Elder. 2011. Her-ring bones in Southeast Alaska archaeologicalsites: The record of Tlingit use of Yaaw (PacificHerring, Clupea pallasii). In The Archaeologyof North Pacific Fisheries (M. L. Moss and A.Cannon, eds.):281–291. Fairbanks: Universityof Alaska Press.

Moss, M. L. and J. M. Erlandson. 2010. Diver-sity in North Pacific shellfish assemblages:The barnacles of Kit’n’Kaboodle Cave, Alaska.Journal of Archaeological Science 37:3359–3369.

Oberg, K. 1973. The Social Economy of the Tlin-git Indians. Seattle: University of WashingtonPress.

Osborn, A. J. 1977. Strandloopers, mermaids, andother fairytales: Ecological determinants of ma-rine resource utilization—The Peruvian case.In For Theory Building in Archaeology (L. R.Binford, ed.):157–205. New York: AcademicPress.

Patton, K. 2010. Reconstructing Houses: EarlyVillage Social Organization in Prince RupertHarbor, British Columbia. Ph.D. Dissertation.Toronto: University of Toronto.

Stewart, F. L. 1975. The seasonal availabilityof fish species used by the Coast Tsimshiansof northern British Columbia. Syesis 8:375–388.

Wessen, G. 1988. The use of shellfish resourceson the Northwest Coast: The view from Ozette.In Prehistoric Economies of the Pacific North-west Coast, Supplement 3, Research in Eco-nomicAnthropology (B.L. Isaac,ed.):197–207.Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

JOURNAL OF ISLAND & COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY 169

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

8:35

21

Oct

ober

201

4