Screening for Speech and Language Delay in Preschool...

Transcript of Screening for Speech and Language Delay in Preschool...

REVIEW ARTICLE

Screening for Speech and Language Delay inPreschool Children: Systematic Evidence Review forthe US Preventive Services Task ForceHeidi D. Nelson, MD, MPHa,b,c, Peggy Nygren, MAa,c, Miranda Walker, BAa,c, Rita Panoscha, MDa,c,d

Departments of aMedical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, bMedicine, and dPediatrics, and the cOregon Evidence-based Practice Center, Oregon Health andScience University, Portland, Oregon

Financial Disclosure: Dr Panoscha has no direct personal financial benefit or conflict of interest involving this research, but there may be a perceived conflict. She is an officer of the Kennedy FellowsAssociation, which had sold and promoted the Clinical Adaptive Test/Clinical Linguistic Auditory Milestone Scale (CAT/CLAMS) test kit in the past. This test instrument is now published, produced, and sold bya private publishing company (Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co). Dr Panoscha excused herself for the portion of this evidence review that reviewed the abstracts and articles on the screening instruments.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Speech and language development is a useful indicator of a child’soverall development and cognitive ability and is related to school success. Identi-fication of children at risk for developmental delay or related problems may leadto intervention services and family assistance at a young age, when the chances forimprovement are best. However, optimal methods for screening for speech andlanguage delay have not been identified, and screening is practiced inconsistentlyin primary care.

PURPOSE.We sought to evaluate the strengths and limits of evidence about theeffectiveness of screening and interventions for speech and language delay inpreschool-aged children to determine the balance of benefits and adverse effects ofroutine screening in primary care for the development of guidelines by the USPreventive Services Task Force. The target population includes all children up to 5years old without previously known conditions associated with speech and lan-guage delay, such as hearing and neurologic impairments.

METHODS. Studies were identified from Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases(1966 to November 19, 2004), systematic reviews, reference lists, and experts. Theevidence review included only English-language, published articles that are avail-able through libraries. Only randomized, controlled trials were considered forexamining the effectiveness of interventions. Outcome measures were consideredif they were obtained at any time or age after screening and/or intervention as longas the initial assessment occurred while the child was �5 years old. Outcomesincluded speech and language measures and other functional and health outcomessuch as social behavior. A total of 745 full-text articles met our eligibility criteriaand were reviewed. Data were extracted from each included study, summarizeddescriptively, and rated for quality by using criteria specific to different studydesigns developed by the US Preventive Services Task Force.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2005-1467

doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1467

KeyWordsspeech and language delay and disorders,preschool children, screening,interventions

AbbreviationsUSPSTF—US Preventive Services TaskForceRCT—randomized controlled trialSES—socioeconomic statusSMD—standard mean differenceCI—confidence interval

Accepted for publication Aug 12, 2005

Address correspondence to Heidi D. Nelson,MD, MPH, Oregon Health and ScienceUniversity, Mail Code BICC 504, 3181 SW SamJackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239. E-mail:[email protected]

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005;Online, 1098-4275). Published in the publicdomain by the American Academy ofPediatrics.

e298 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

RESULTS. The use of risk factors for selective screening hasnot been evaluated, and a list of specific risk factors toguide primary care physicians has not been developed ortested. Sixteen studies about potential risk factors forspeech and language delay in children enrolled hetero-geneous populations, had dissimilar inclusion and exclu-sion criteria, and measured different risk factors andoutcomes. The most consistently reported risk factorsincluded a family history of speech and language delay,male gender, and perinatal factors. Other risk factorsreported less consistently included educational levels ofthe mother and father, childhood illnesses, birth order,and family size.

The performance characteristics of evaluation tech-niques that take �10 minutes to administer were de-scribed in 24 studies relevant to screening. Studies thatwere rated good to fair quality reported wide ranges ofsensitivity and specificity when compared with referencestandards (sensitivity: 17–100%; specificity: 45–100%).Most of the evaluations, however, were not designed forscreening purposes, the instruments measured differentdomains, and the study populations and settings wereoften outside of primary care. No “gold standard” hasbeen developed and tested for screening, reference stan-dards varied across studies, few studies compared theperformance of �2 screening techniques in 1 popula-tion, and comparisons of a single screening techniqueacross different populations are lacking.

Fourteen good- and fair-quality randomized, controlledtrials of interventions reported significantly improvedspeech and language outcomes compared with controlgroups. Improvement was demonstrated in several do-mains including articulation, phonology, expressive lan-guage, receptive language, lexical acquisition, and syn-tax among children in all age groups studied and acrossmultiple therapeutic settings. Improvement in otherfunctional outcomes such as socialization skills, self-es-teem, and improved play themes were demonstrated insome, but not all, of the 4 studies that measured them. Ingeneral, studies of interventions were small and hetero-geneous, may be subject to plateau effects, and reportedshort-term outcomes based on various instruments andmeasures. As a result, long-term outcomes are notknown, interventions could not be compared directly,and generalizability is questionable.

CONCLUSIONS.Use of risk factors to guide selective screeningis not supported by studies. Several aspects of screeninghave been inadequately studied to determine optimalmethods, including which instrument to use, the age atwhich to screen, and which interval is most useful. Trialsof interventions demonstrate improvement in some out-come measures, but conclusions and generalizability arelimited. Data are not available addressing other key is-sues including the effectiveness of screening in primary

care settings, role of enhanced surveillance by primarycare physicians before referral for diagnostic evaluation,non–speech and language and long-term benefits of in-terventions, and adverse effects of screening and inter-ventions.

SPEECH AND LANGUAGE development is considered byexperts to be a useful indicator of a child’s overall

development and cognitive ability1 and is related toschool success.2–7 Identification of children at risk fordevelopmental delay or related problems may lead tointervention services and family assistance at a youngage when chances for improvement are best.1 This ratio-nale supports preschool screening for speech and lan-guage delay, or primary language impairment/disorder,as a part of routine well-child care.

Several types of speech and language delay and dis-orders have been described,8 although terminology var-ies (Table 1). Expressive language delay may exist with-out receptive language delay, but often they occurtogether in children as a mixed expressive/receptive lan-guage delay. Some children also have disordered lan-guage. Language problems can involve difficulty withgrammar (syntax), words or vocabulary (semantics),the rules and system for speech sound production (pho-nology), units of word meaning (morphology), and theuse of language particularly in social contexts (pragmat-ics). Speech problems may include stuttering or dysflu-ency, articulation disorders, or unusual voice quality.Language and speech problems can exist together or bythemselves.

Prevalence rates for speech and language delay havebeen reported across wide ranges. A recent Cochrane

TABLE 1 Definitions of Terms

Term Definition

Articulation The production of speech soundsDysfluency Interrupted flow of speech sounds, such as

stutteringExpressive language The use of language to share thoughts, protest, or

commentLanguage The conceptual processing of communication

which may be receptive and or expressiveMorphology The rules governing meanings of word unitsPhonology The set of rules for sound productionPragmatics Adaptation of language to the social contextProsody Appropriate intonation, rate, rhythm, and

loudness of speech utterancesReceptive language Understanding of languageSemantics A set of words known to a person that are a part

of a specific language (vocabulary)Speech Verbal production of languageSyntax The way linguistic elements are put together to

form phrases or clauses (grammar)Voice disorders Difficulty with speech sound production, at the

level of the larynx, may be related to motor oranatomical issues (eg, hypernasal or hoarsespeech)

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e299 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

review summarized prevalence data on speech delay,language delay, and combined delay in preschool- andschool-aged children.9 For preschool-aged children, 2 to4.5 years old, studies that evaluated combined speechand language delay have reported prevalence rates rang-ing from 5% to 8%,10,11 and studies of language delayhave reported prevalence rates ranging from 2.3% to19%.9,12–15 Untreated speech and language delay in pre-school children has shown variable persistence rates(from 0% to 100%), with most studies reporting 40% to60%.9 In 1 study, two thirds of preschool-aged childrenwho were referred for speech and language therapy andgiven no direct intervention proved eligible for therapy12 months later.16

Preschool-aged children with speech and languagedelay may be at increased risk for learning disabilitiesonce they reach school age.17 They may have difficultyreading in grade school,2 exhibit poor reading skills atage 7 or 8,3–5 and have difficulty with written language,6

in particular. This may lead to overall academic under-achievement7 and, in some cases, lower IQ scores13 thatmay persist into young adulthood.18 As adults, childrenwith phonological difficulties may hold lower-skilledjobs than their non–language-impaired siblings.19 In ad-dition to persistent speech- and language-related under-achievement (verbal, reading, spelling), language-de-layed children have also shown more behavior problemsand impaired psychosocial adjustment.20,21

Assessing children for speech and language delay anddisorders can involve a number of approaches, althoughthere is no uniformly accepted screening technique foruse in the primary care setting. Milestones for speechand language development in young children are gen-erally acknowledged.22 Concerns for delay arise if thereare no verbalizations by the age of 1, if speech is notclear, or if speech or language is different from that ofother children of the same age. Parent questionnaires andparent concern are often used to detect delay.23 Most for-mal instruments were designed for diagnostic purposes andhave not been widely evaluated for screening. Instrumentsconstructed to assess multiple developmental components,such as the Ages and Stages Questionnaire,24 Clinical Adap-tive Test/Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale,25

and Denver Developmental Screening Test,26 includespeech and language components. Instruments designedspecific for communication domains include the McArthurCommunicative Development Inventory,27 Ward InfantLanguage Screening Test, Assessment, Acceleration, andRemediation (WILSTAAR),28 Fluharty Preschool Speechand Language Screening Test,29 Early Language Mile-stone Scale,30 and several others.

A specific diagnosis is made most often by a speechand language specialist using a battery of instruments.Once a child has been diagnosed with a speech and/orlanguage delay, interventions may be prescribed. Ther-apy takes place in various settings including speech and

language specialty clinics, home, and schools or class-rooms. Direct therapy or group therapy provided by aclinician, caretaker, or teacher can be child-centeredand/or include peer and family components. The dura-tion of the intervention varies. Intervention strategiesfocus on �1 domains depending on individual needs,such as expressive language, receptive language, pho-nology, syntax, and lexical acquisition. Therapies caninclude naming objects, modeling and prompting, indi-vidual or group play, discrimination tasks, reading, andconversation.

It is not clear how consistently clinicians screen forspeech and language delay in primary care practice. In 1study, 43% of parents reported that their young child(aged 10–35 months) did not receive any type of devel-opmental assessment at their well-child visit, and 30%of parents reported that their child’s physician had notdiscussed how the child communicates.31 Potential bar-riers to screening include lack of time, no clear protocols,and the competing demands of the primary care visit.

This evidence review focuses on the strengths andlimits of evidence about the effectiveness of screeningand interventions for speech and language delay in pre-school-aged children. Its objective is to determine thebalance of benefits and adverse effects of routine screen-ing in primary care for the development of guidelines bythe US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Thetarget population includes all children up to 5 years oldwithout previously known conditions associated withspeech and language delay, such as hearing and neuro-logic impairments. The evidence synthesis emphasizesthe patient’s perspective in the choice of tests, interven-tions, outcome measures, and potential adverse effectsand focuses on those that are available and easily inter-preted in the context of primary care. It also considersthe generalizability of efficacy studies performed in con-trolled or academic settings and interprets the use of thetests and interventions in community-based populationsseeking primary health care.

METHODS

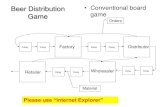

Analytic Framework and Key QuestionsEvidence reviews for the USPSTF follow a specific meth-odology32 beginning with the development of an analyticframework and key questions in collaboration withmembers of the USPSTF. The analytic framework repre-sents an outline of the evidence review and includes thepatient population, interventions, outcomes, and ad-verse effects of the screening process (Fig 1). Corre-sponding key questions examine a chain of evidenceabout the effectiveness, accuracy, and feasibility ofscreening children aged 5 years and younger for speechand language delay in primary care settings (key ques-tions 1 and 2), adverse effects of screening (key question3), the role of enhanced surveillance in primary care

e300 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

(key question 4), effectiveness of interventions for chil-dren identified with delay (key questions 5, 6, and 7),and adverse effects of interventions (key question 8).

Studies addressing key question 1, corresponding tothe overarching arrow in Fig 1, would include all com-ponents in the continuum of the screening process, in-cluding the screening evaluation, diagnostic evaluationfor children identified with delay by the screening eval-uation, interventions for children diagnosed with delay,and outcome measures allowing determination of theeffectiveness of the overall screening process. Enhancedsurveillance in primary care relates to the practice ofclosely observing children who may have clinical con-cern for delay but not of the degree warranting a referral(“watchful waiting”). Outcome measures in this reviewinclude speech- and language-specific outcomes as wellas non–speech and language health and functional out-comes such as social behavior, self-esteem, family func-tion, peer interaction, and school performance. Keyquestion 5 examines whether speech and language in-

terventions lead to improved speech and language out-comes. Key question 6 examines whether speech andlanguage interventions lead to improved non–speechand language outcomes. Key question 7 evaluates thesubsequent effects of improved speech and language,such as improved school performance at a later age.

Literature Search and SelectionRelevant studies were identified from multiple searchesof Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases (1966 toNovember 19, 2004). Search terms were determined bythe investigators and a research librarian and are de-scribed elsewhere.33 Articles were also obtained fromrecent systematic reviews,34,35 reference lists of pertinentstudies, reviews, editorials, and Web sites and by con-sulting experts. In addition, the investigators attemptedto collect instruments and accompanying manuals; how-ever, these materials are not generally available andmust be purchased, which limited the evidence reviewto published articles.

FIGURE 1Analytic framework and key questions. The analytic framework represents an outline of the evidence review and includes the patient population, interventions, outcomes, and adverseeffects of the screening process. The key questions examine a chain of evidence about the effectiveness, accuracy, and feasibility of screening children aged 5 years and younger forspeech and language delay in primary care settings (key questions 1 and 2), adverse effects of screening (key question 3), the role of enhanced surveillance in primary care (key question4), effectiveness of interventions for children identified with delay (key questions 5, 6, and 7), and adverse effects of interventions (key question 8).

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e301 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

The investigators reviewed all abstracts that wereidentified by the searches and determined eligibility offull-text articles based on several criteria. Eligible articleshad English-language abstracts, were applicable to USclinical practice, and provided primary data relevant tokey questions. Studies of children with previously diag-nosed conditions known to cause speech and languagedelay (eg, autism, mental retardation, fragile X syn-drome, hearing loss, degenerative and other neurologicdisorders) were not included because the scope of thisreview is screening children without known diagnoses.

Studies of risk factors were included if they focusedon children aged 5 years or younger, reported associa-tions between predictor variables and speech and lan-guage outcomes, and were relevant to selecting candi-dates for screening. Otitis media as a risk factor forspeech and language delay is a complex and controver-sial area and was not included in this review.

Studies of techniques to assess speech and languagewere included if they focused on children aged 5 yearsand younger, could be applied to a primary care setting,used clearly defined measures, compared the screeningtechnique to an acceptable reference standard, and re-ported data that allowed calculation of sensitivity andspecificity. Techniques that take �10 minutes to com-plete and could be administered in a primary care settingby nonspecialists are most relevant to screening and aredescribed in this report. Instruments that take �10 min-utes and up to 30 minutes or for which administrationtime was not reported are described elsewhere.33 In gen-eral, if the instrument was administered by primary carephysicians, nurses, research associates, or other nonspe-cialists for the study, it was assumed that it could beadministered by nonspecialists in a clinic. For question-able cases, experts in the field were consulted to helpdetermine appropriateness for primary care. Studies ofbroader developmental screening instruments such asthe Ages and Stages Questionnaire and Denver Devel-opmental Screening Test were included if they providedoutcomes related to speech and language delay specifi-cally.

Only randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) were con-sidered for examining the effectiveness of interventions.Outcome measures were considered if they were ob-tained at any time or age after screening and/or inter-vention as long as the initial assessment occurred whilethe child was �5 years old. Outcomes included speechand language measures as well as other functional andhealth outcomes as described previously.

Data Extraction and SynthesisInvestigators reviewed 5377 abstracts that were identi-fied by the searches. A total of 690 full-text articles fromsearches and an additional 55 nonduplicate articles fromreference lists and experts met eligibility criteria andwere reviewed. Data were extracted from each study,

entered into evidence tables, and summarized by de-scriptive methods. For some studies of screening instru-ments, sensitivity and specificity were calculated by theinvestigators if adequate data were presented in thearticle. No statistical analyses were performed because ofthe heterogeneity of studies. The investigators indepen-dently rated the quality of studies by using criteria spe-cific to different study designs developed by the USPSTF(Appendix).32 The quality of the study does not neces-sarily indicate the quality of an instrument or interven-tion but may influence interpretation of the results ofthe study.

RESULTS

Key Question 1: Does Screening for Speech and LanguageDelay Result in Improved Speech and Language as well asImproved Other Non–Speech and Language Outcomes?No studies directly addressed this question.

Key Question 2: Do Screening Evaluations in the Primary CareSetting Accurately Identify Children for Diagnostic Evaluationand Interventions?

Key Question 2a: Does Identification of Risk Factors ImproveScreening?Nine studies conducted in English-speaking popula-tions36–44 and 7 studies from non–English-speaking pop-ulations45–51 met inclusion criteria (Table 2). The mostconsistently reported risk factors include a family historyof speech and language delay, male gender, and perina-tal risk factors; however, their role in screening is un-clear. A list of specific risk factors to guide primary carephysicians in selective screening has not been developedor tested.

English-language studies include case-control,37,39–41,43

cross-sectional,36,38,42 and prospective-cohort44 designs.Most studies evaluated risk for language delay with orwithout speech delay, and 1 restricted the evaluation toexpressive language only.44 Family history was the mostconsistent significantly associated risk factor in 5 of 7studies that examined it.37,39,41–43 Family history was de-fined as family members who were late to talk or hadlanguage disorders, speech problems, or learning prob-lems. Male gender was a significant factor in all 3 of thestudies that examined it.37,39,42 Three37,41,43 of 5 studiesreported an association between lower maternal educa-tion level and language delay, and 3 studies41–43 of 4 thatevaluated paternal education level reported a similarrelationship. Other associated risk factors that were re-ported less consistently included childhood illnesses,36,40

born late in the family birth order,42 family size,39 olderparents39 or younger mother43 at birth, and low socio-economic status (SES) or minority race.40 One study thatevaluated history of asthma found no association withspeech and language delay.39

The 7 studies that assessed risk in non–English-speak-

e302 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

TABLE2

Summaryof

Stud

iesof

Risk

Factors

Authors(y)

Popu

latio

nAg

e,mo

Speech

andLang

uage

Dom

ains

Family

History

Male

Gender

SES

Birth

Order

Perin

atal

Factors

Parental

Education

Medical

Cond

ition

sOtherAssociations

English

-language

studies

Brookhouseretal36(1979)

24referredfromBoysTown

Institute

28–62

Language

bNR

NR

NR

NR

NR

aNR

Campbelletal37(2003)

398casesand

241controls

fromalarge,prospective

studyinPittsburgh,PA

36Speech

aa

aNR

NR

Mothera

NR

NR

Cantwelland

Baker38(1985)

600childrenreferredfroma

speech

andhearingclinicin

LosA

ngeles,CA

20–191

Multipletypes

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

Psychiatric,behavioral,or

developm

ental

disordera

ChoudhuryandBenasich3

9

(2003)

42casesw

ithpositivefamily

historiesand

94controls

fromtheNew

YorkCity,NY,

area

36Language

aa

bNR

NR

MotherbFatherb

Asthmab

Olderparents,a

more

childreninfamily

a

Singeretal

40(2001)

98cases(VLBW

/BPD

),70

VLBW

/non-BPD

controls,

and95

term

controlsfrom

Cleveland,OH,region

hospitals

36Language

NR

NR

aNR

NR

NR

BPD,aPD

AaNeurologicrisk,aminority

race

a

Tallaletal41(1989)

76casesand

54controlsfrom

theSanDiego,CA,

LongitudinalStudy

48–59

Language

aNR

NR

NR

NR

MotheraFathera

NR

NR

Tomblinetal

42(1991)

662fromalongitudinalcohort

30–60

Speech

andlanguage

aa

NR

Bornlatera

NR

MotherbFathera

NR

NR

Tomblinetal

43(1997)

177casesand

925controls

frommetropolitan

regions

ofIowaorIllinois

Kindergartenage

Speech

andlanguage

aNR

NR

NR

Lowbirth

weightb

MotheraFathera

NR

Youngerm

other,aless

breastfeedinga

Whitehurstetal44(1991)

62casesand

55controlsfrom

Long

Island,NY

24–38

Expressivelanguage

bNR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

Non–English-language

studies

Foxetal

45(2002)(Germany)

65casesand

48controls

32–86

Speech

aNR

NR

NR

Birth

difficulties,a

suckinghabitsa

NR

NR

NR

KleinandTzuriel46(1986)

(Israel)

72kindergartenchildrenfrom

amiddle-classu

rban

area

48–108

Vocabulary

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

Child’sbehaviorb

Klothetal

47(1995)

(Netherlands)

93referredbecause1orboth

parentsw

erestutterersor

hadahistoryofstuttering

23–58

Stuttering

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

Motherstutters,b

Mother’sspeaking

style

orrateb

Lyytinen

etal

48(2001)(Finland)107with

familialriskof

dyslexiaand93

without

0–54

Speech

andlanguage

aNR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

Petersetal

49(1997)

(Netherlands)

946fromaDutch

birth

cohort

inNijm

egen

84–96

Language

andeducational

attainment

NR

bNR

NR

Preterm,blow

birth

weightb

aNR

Dutch

asasecond

language

a

Weindrichetal

50(2000)

(Germany)

320recruitedatbirth

ata

Germ

anhospital

Tested

at54

and

96mo

Receptiveandexpressive

language

andarticulation

(54mo);reading

and

spelling(96mo)

NR

NR

NR

NR

Preterm,a

toxemia,alow

birth

weighta

MotheraFathera

NR

Parentalpsychiatric

disorder,a

overcrow

ding,a

parentalbroken

home

ordelinquency,a

1-parentfamily,a

unwantedpregnancya

Yliherva

etal

51(2001)(Finland)

8370

recruitedatbirth

from2

north

ernprovinceso

fFinland(99%

ofpregnant

wom

enin1985–1986)

96Speech,language,learning,

motorabilities

NR

aNR

NR

Preterm,alow

birth

weighta

Motherb

Impaired

hearinga

Mother’sage,b

�4

childreninfamily,a

reconstru

cted

family

status

a

NRindicatesn

otreported;VLBW

,verylowbirth

weight;BPD,bronchopulmonarydysplasia;PDA,patentductus

arteriosus.

aStatisticallysig

nificantassociation.

bVariablewasexam

ined

andnotassociatedwith

delay.

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e303 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

TABLE 3 Instruments Used in Studies

Instrument Abbreviation Components Authors (y)

Bayley Infant NeurodevelopmentalScreenera

BINS Assesses 4 areas: (1) neurological function/intactness; (2)receptive function; (3) expressive function; and (4)cognitive processes

Macias et al62 (1998)

Clinical Adaptive Test/Clinical LinguisticAuditory Milestone Scale

CAT/CLAMS Includes psychometrics and speech and languagemilestones; CAT: 19 age sets with 12 instruments and57 items for visual motor skills; CLAMS: 19 age setswith 3 instruments up to 24 mo and 4 instrumentsafter 24 mo; includes 43 items for language skills

Clark et al58 (1995)

Denver Developmental Screening Test-IIa

DDST II Domains include (1) language; (2) fine motor-adaptive;(3) personal-social; and (4) gross motor

Glascoe and Byrne57 (1993)

Developmental Profile-IIa DP-II 5 subsets: (1) physical; (2) self-help; (3) social; (4)academic; and (5) communication

Glascoe and Byrne57 (1993)

Early Language Milestone Scale 41 items covering 4 areas: (1) auditory expressive; (2)auditory receptive; (3) visual expressive; and (4) visualreceptive

Coplan et al30 (1982); Black etal55 (1988); Walker et al68

(1989)Fluharty Preschool Speech andLanguage Screening Test

35 items separated into 3 sections (A–C) includingidentification of 15 common objects (phoneme),nonverbal responses to 10 sentences (syntax), andimitation of 10 1-sentence picture descriptions; assessidentification, articulation, comprehension, andrepetition

Blaxley et al65 (1983); Sturner etal53 (1993); Allen and Bliss69

(1987)

Hackney Early Language Screening Test 20-item test in 7 sections: (1) comprehension: followinginstructions to manipulate toys; (2) expression: testermanipulates toys and asks child questions about this;(3) comprehension: following instructions for placingtoys; (4) comprehension: child chooses picture from 3options; (5) expression: child answers question aboutpictures; (6) expression: child names objects; and (7)comprehension: child chooses picture from 4 options

Dixon et al54 (1988); Law67

(1994)

Language Development Survey LDS 310 words arranged in 14 semantic categories; parentsindicate which words their child has spoken anddescribe word combinations of �2 words that theirchild has used

Klee et al59 (1998); Klee et al60

(2000); Rescorla and Alley61

(2001)

Levett-Muir Language Screening Test Test is divided into 6 sections: (1) comprehension: childis asked to pick toys from group; (2) vocabulary: child’sability to name the toys; (3) comprehension: usingpictures, child is required to respond to questions; (4)vocabulary: child’s ability to name what’s in thepictures; (5) comprehension and representation:child’s ability to answer “what” and “who” questions;and (6) overall: child is asked to explain the detailedcomposite picture

Levett and Muir64 (1983)

Parent Evaluation of DevelopmentalStatus

PEDS 2 questions for parents to elicit concerns in general andspecific areas; other items determine reasons forparents’ concerns

Glascoe56 (1991)

Parent Language Checklista PLC 12 questions for parents about their child’s receptive andexpressive language including 1 question forassessing hearing problems

Burden et al11 (1996)

Pediatric Language AcquisitionScreening Tool for Early Referral

PLASTER Communication development milestones by age with 7individual areas; each area contains 10 questions (5relate to receptive language and 5 to expressivelanguage)

Sherman et al52 (1996)

Screening Kit of LanguageDevelopment

SKOLD Vocabulary comprehension, story completion, sentencecompletion, paired-sentence repetition with pictures,individual sentence repetition with pictures,individual sentence repetition without pictures, andauditory comprehension of commands

Bliss and Allen66 (1984)

Sentence Repetition Screening Test SRST 15 sentences repeated 1 at a time by the child afterdemonstration by the tester

Sturner et al71 (1996)

Structured Screening Test 20 questions covering both expressive and receptivelanguage skills

Laing et al63 (2002)

Test for Examining ExpressiveMorphology

TEEM 54 items targeting a variety of morphosyntacticstructures using a sentence-completion task

Merrell and Plante70 (1997)

a Speech and language are part of a broader screening instrument.

e304 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

ing populations included case-control,47 cross-section-al,45 prospective-cohort,48–51 and concurrent-compari-son46 designs. Studies evaluated several types of delayincluding vocabulary,46 speech,45 stuttering,47 lan-guage,48–51 and learning.49–51 Significant associations werereported in the 2 studies that evaluated family history45,48

and 1 of 2 studies that evaluated male gender.51 Three of4 non–English-language studies, including a cohort of

�8000 children in Finland,51 reported significant associ-ations with perinatal risk factors such as prematurity,50,51

birth difficulties,45 low birth weight,50,51 and sucking hab-its.45 An association with perinatal risk factors was notfound in the 1 English-language study that examinedlow birth weight.43 Other associated risk factors thatwere reported less consistently include parental educa-tion level49,50 and family factors such as size and over-

TABLE 4 Studies of Screening Instruments for Children Up to 2 Years Old

Authors (y) N Instrument Reference Standard Speech and LanguageDomains

Under 5 min to administerGlascoe56 (1991) 157 Parent Evaluation of Developmental

StatusClinical assessment Expressive language,

articulation

Coplan et al30 (1982) 191 Early Language Milestone Scale Clinical assessment Expressive and receptivelanguage

Black et al55 (1988) 48 Early Language Milestone Scale Receptive-Expressive EmergentLanguage Scale, BayleyScales of InfantDevelopment

Expressive and receptivelanguage

5–10 min to administerGlascoe and Byrne57 (1993)Study 1

89 Developmental Profile II Battery of measures Fine motor adaptive, personalsocial, gross motor, andlanguage

Sherman et al52 (1996) 173 Pediatric Language AcquisitionScreening Tool for Early Referral

Early Language Milestone Scale Expressive and receptivelanguage

10 min to administerMacias et al62 (1998) 78 Bayley Infant Neurodevelopmental

ScreenerBayley Scales of InfantDevelopment II

Expressive and receptivelanguage

Klee et al59 (1998) 306 Language Development Survey Infant Mullen Scales of EarlyLearning

Expressive vocabulary

Klee et al60 (2000) 64 Language Development Survey Infant Mullen Scales of EarlyLearning

Expressive vocabulary

Rescorla and Alley61 (2001) 422 Language Development Survey Bayley Scales of InfantDevelopment, Stanford-Binet, ReynellDevelopmental LanguageScales

Expressive vocabulary: delay 1,�30 words and no wordcombinations; delay 2,�30 words or no wordcombinations; delay 3,�50 words or no wordcombinations

Clark et al58 (1995) 99 Clinical Linguistic and AuditoryMilestone Scale

Sequenced Inventory ofCommunicationDevelopment

Syntax, pragmatics

Glascoe and Byrne57 (1993)Study 2

89 Denver Developmental ScreeningTest II (communicationcomponents)

Battery of measures Physical, self-help, social,academic, andcommunication

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e305 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

crowding.50,51 These studies did not find associations withthe mother’s stuttering or speaking style or rate,47 themother’s age,51 or child temperament.46

Key Questions 2b and 2c: What Are Screening Techniquesand How Do They Differ by Age? What Is the Accuracy ofScreening Techniques and How Does It Vary by Age?A total of 22 articles that reported performance charac-teristics of 24 evaluations met inclusion criteria.33 The

studies used several different standardized and non-standardized instruments (Table 3), although manywere not designed specifically for screening purposes.Results of the instruments were compared with those ofa variety of reference standards, and no “gold standard”was acknowledged or used across studies, which limitedcomparisons between them.

The studies provided limited demographic details ofsubjects, and most included predominantly white chil-

TABLE 4 Continued

Subjects Setting Screener Sensitivity, % Specificity, % Study QualityRating

From outpatient clinic orprivate practice; 78% white;54% male; 6–77 mo

Clinic Doctoral students in psychologyor special education

72 83 Good

From private practices andpediatric outpatients ofhospital; 80% white; 50%male; 0–36 mo

Physician’s office Medical students 97 93 Fair

From low socioeconomicgroups; 8–22 mo

Large pediatric clinic,university teachinghospital

Not reported 83 100 Poor

From 5 day care centers; 52%male; 7–70 mo

Day care centers Psychologist 73 76 Fair

123 high-risk infants; 50normal controls; 3–36 mo

High risk: neonataldevelopmentalfollow-up clinic;control: speechand hearing clinic

Speech and languagepathologist and graduatestudents

53 86 Fair

Randomly selected from thosepresenting for routineneonatal high-risk follow-up; 54% male; 62% black;6–23 mo

Physician’s office Developmental pediatrician 73 (using middle-cut scores)

66 (using middle-cut scores)

Fair

Toddlers turning 2 y old duringthe study in Wyoming; 52%male; 24–26 mo

Home Parent 91 87 Good-Fair

Children turning 2 y in aspecific month in an area ofWyoming

Home Parent 83 (at age 2); 67 (atage 3)

97 (at age 2); 93 (atage 3)

Fair

Toddlers in 4 townships ofDelaware County, PA,turning 2 y old during thestudy

Home Parent and research assistant Delay 1: 70 (Bayley),52 (Binet), 67(Reynell); delay 2:75 (Bayley), 56(Binet), 89(Reynell); delay 3:80 (Bayley), 64(Binet), 94(Reynell)

Delay 1: 99 (Bayley),98 (Binet), 94(Reynell); delay 2:96 (Bayley), 95(Binet), 77(Reynell); delay 3:94 (Bayley), 94(Binet), 67(Reynell);

Fair

Infants turning 1 or 2 y oldduring study; 55% male;0–36 mo

Home or school forthe deaf

Speech and languagepathologist

Receptive: 83 (14–24 mo), 68 (25–36 mo);expressive: 50(14–24 mo), 88(25–36 mo)

Receptive: 93 (14–24 mo), 89 (25–36 mo);expressive: 91(14–24 mo), 98(25–36 mo)

Fair

Children from 5 day carecenters; 52% male: 7–70 mo

Day care centers Psychologist 22 86 Fair

e306 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

dren with similar proportions of boys and girls. Onestudy enrolled predominantly black children52 and an-other children from rural areas.53 Study sizes rangedfrom 25 subjects54 to 2590 subjects.11 Testing was con-ducted in general health clinics, specialty clinics, daycare centers, schools, and homes by pediatricians,nurses, speech and language specialists, psychologists,health visitors, medical or graduate students, teachers,parents, and research assistants. Studies are summarizedbelow by age categories according to the youngest agesincluded, although many studies included children inoverlapping age categories.

Ages 0 to 2 YearsEleven studies from 10 publications used instruments

that take �10 minutes to administer for children up to 2years old, including the Early Language MilestoneScale,30,55 Parent Evaluation of Developmental Status,56

Denver Developmental Screening Test II (language com-ponent),57 Pediatric Language Acquisition ScreeningTool for Early Referral,52 Clinical Linguistic and AuditoryMilestone Scale,58 Language Development Survey,59–61

Development Profile II,57 and the Bayley Infant Neuro-developmental Screener62 (Table 4). Of these studies, 6tested expressive and/or receptive language,30,52,55,57,62 3tested expressive vocabulary,59–61 1 tested expressive lan-guage and articulation,56 and 1 tested syntax and prag-matics.58

For the 10 fair- and good-quality studies that pro-vided data to determine sensitivity and specificity, sen-sitivity ranged from 22% to 97% and specificity rangedfrom 66% to 97%.30,52,56–62 Four studies reported sensi-tivity and specificity of �80% when using the EarlyLanguage Milestone Scale,30 the Language DevelopmentSurvey,59,60 and the Clinical Linguistic and Auditory

TABLE 5 Studies of Screening Instruments for Children 2 to 3 Years Old

Authors (y) N Instrument Reference Standard Speech and LanguageDomains

5 min to administerBurden et al11

(1996)2590 Parent Language Checklist Clinical judgement Expressive and receptive

languageLaing et al63

(2002)376 Structured Screening Test Reynell Developmental Language

ScalesExpressive and receptivelanguage

Levett and Muir64

(1983)140 Levett-Muir Language

Screening TestReynell Developmental LanguageScales, Goldman-Fristoe Test ofArticulation, LanguageAssessment and RemediationProcedure

Receptive language,phonology, syntax

Sturner53 (1993)Study 1

279 Fluharty Preschool Speechand LanguageScreening Test

Arizona Articulation ProficiencyScale Revised, Test of LanguageDevelopment Primary

Expressive and receptivelanguage, articulation

Sturner et al53

(1993) Study 2421 Fluharty Preschool Speech

and LanguageScreening Test

Test for Auditory Comprehensionof Language Revised, Templin-Darley Test of Articulation

Expressive and receptivelanguage, articulation

10 min to administerLaw67 (1994) 1205 Hackney Early Language

Screening TestReynell Developmental LanguageScales

Expressive language

Blaxley65 (1983) 90 Fluharty Preschool Speechand LanguageScreening Test

Developmental Sentence Scoring Expressive and receptivelanguage, articulation

Bliss and Allen66

(1984)602 Screening Kit of Language

DevelopmentSequenced Inventory ofCommunication Development

Expressive and receptivelanguage

Dixon et al54

(1988)25 Hackney Early Language

Screening TestClinical judgement Expressive language

Walker et al68

(1989)77 Early Language Milestone

ScaleSequenced Inventory ofCommunication Development

Expressive and receptivelanguage

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e307 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

Milestone Scale.58 The study of the Clinical Linguisticand Auditory Milestone Scale also determined sensitivityand specificity by age and reported higher sensitivity/specificity at 14 to 24 months of age (83%/93%) than 25to 36 months of age (68%/89%) for receptive functionbut lower sensitivity/specificity at 14 to 24 months of age(50%/91%) than 25 to 36 months of age (88%/98%) forexpressive function.58 A study that tested expressive vo-cabulary by using the Language Development Surveyindicated higher sensitivity/specificity at 2 years of age(83%/97%) than at 3 years of age (67%/93%).60

Ages 2 to 3 YearsTen studies in 9 publications used instruments that

take �10 minutes to administer for children aged 2 to 3,including the Parent Language Checklist,11 StructuredScreening Test,63 Levett-Muir Language Screening Test,64

Fluharty Preschool Speech and Language Screening

Test,53,65 Screening Kit of Language Development,66

Hackney Early Language Screening Test,54,67 and EarlyLanguage Milestone Scale68 (Table 5). All the studiestested expressive and/or receptive language.11,53,54,63–68 Inaddition, 3 studies tested articulation,53,65 and 1 studiedsyntax and phonology.64

For the 8 fair- and good-quality studies that provideddata to determine sensitivity and specificity, sensitivityranged from 17% to 100% and specificity ranged from45% to 100%. Two studies reported sensitivity and spec-ificity of �80% when using the Levett-Muir LanguageScreening Test64 and the Screening Kit of Language De-velopment.66 The study of the Screening Kit of LanguageDevelopment reported comparable sensitivity/specificityat 30 to 36 months (100%/98%), 37 to 42 months(100%/91%), and 43 to 48 months of age (100%/93%).66

TABLE 5 Continued

Subjects Setting Screener Sensitivity, % Specificity, % Study QualityRating

All children turning 36 mo;52% male; 41% urban

Home (mailed) Parent 87 45 Good

Children from 2 low-SEScounties in London;mean age: 30 mo

Physician’s office Health visitor 66 (severe); 54 (needstherapy)

89 (severe); 90 (needstherapy)

Fair

Private practicepopulation; 34–40 mo

Physician’s office Medical practitioners 100 100 Fair

46% male; 74% white;86% rural; 24–72 mo

Preschool Teacher 43 (speech and language);74 (speech); 38(language)

82 (speech and language);96 (speech); 85(language)

Fair

52% male; 75% white;24–72 mo

Preschool Teacher 31 (speech and language);43 (speech); 17(language)

93 (speech and language);93 (speech); 97(language)

Fair

Children attending routinedevelopmentalcheckups; mean age: 30mo

Home Health visitor 98 69 Good-Fair

Children referred forspeech and/or languageassessment andintervention andcontrols; 24–72 mo

Speech and hearingclinic in westernOntario

Clinician 36 (10th percentile); 30(25th percentile)

95 (10th percentile); 100(25th percentile)

Fair

From day care centers inDetroit, MI; 30–48 mo

Speech andlanguage hearingclinic, day-carecenter,physician’s office,educational andhealth facilities

Paraprofessionals and speechand language pathologists

100 (30–36 mo); 100 (37–42 mo); 100 (43–48 mo)

98 (30–36 mo); 91 (37–42mo); 93 (43–48 mo)

Fair

Pilot study at 1 clinicsetting in Hackney;mean age: 30 mo

Physician’s office Health visitor 95 94 Poor

All children attending astudy clinic; mean age:36 mo

Clinic Speech and languagepathologist

0 (0–12 mo); 100 (13–24mo); 100 (25–36 mo)

86 (0–12 mo); 60 (13–24mo); 75 (25–36 mo)

Poor

e308 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

Ages 3 to 5 YearsThree studies used instruments that take �10 min-

utes to administer, including the Fluharty PreschoolSpeech and Language Screening Test,69 Test for Exam-ining Expressive Morphology,70 and the Sentence Repe-tition Screening Test71 (Table 6). Of these studies, 2tested expressive and receptive language and articula-tion,69,71 and 1 tested expressive vocabulary and syntax.70

The 2 fair-quality studies reported sensitivity rangingfrom 57% to 62% and specificity ranging from 80% to95%.66,69,71

Systematic ReviewA Cochrane systematic review of 45 studies, including

most of the studies cited above, summarized the sensi-tivity and specificity of instruments that take �30 min-utes to administer.34 Sensitivity of the instruments fornormally developing children ranged from 17% to100% and for children from clinical settings it rangedfrom 30% to 100%. Specificity ranged from 43% to100% and 14% to 100%, respectively. Studies consid-ered to be of higher quality tended to have higher spec-ificity than sensitivity (t � 4.41; P � .001); however,high false-positive and false-negative rates were re-ported often.34

Key Question 2d: What Are the Optimal Ages and Frequencyfor Screening?No studies addressed this question.

Key Question 3: What Are the Adverse Effects of Screening?No studies addressed this question. Potential adverseeffects include false-positive and false-negative results.False-positive results can erroneously label children withnormal speech and language as impaired, potentiallyleading to anxiety for children and families and addi-tional testing and interventions. False-negative resultswould miss identifying children with impairment, po-tentially leading to progressive speech and language de-lay and other long-term effects including communica-tion, social, and academic problems. In addition, oncedelay is identified, children may be unable to accessservices because of unavailability or lack of insurancecoverage.

Key Question 4: What Is the Role of Enhanced Surveillance byPrimary Care Clinicians?No studies addressed this question.

Key Question 5: Do Interventions for Speech and LanguageDelay Improve Speech and Language Outcomes?Twenty-five RCTs in 24 publications met inclusion cri-teria, including 1 rated good,72 13 rated fair,73–85 and 11rated poor quality77,86–95 (Table 7). Studies were consid-ered to be of poor quality if they reported importantdifferences between intervention and comparison

groups at baseline, did not use intention-to-treat analy-sis, no method of randomization was reported, or therewere �10 subjects in the intervention or comparisongroups. Limitations of studies, in general, include smallnumbers of participants (only 4 studies enrolled �50subjects), lack of consideration of potential confounders,and disparate methods of assessment, intervention, andoutcome measurement. As a result, conclusions abouteffectiveness are limited. Although children in the stud-ies ranged from 18 to 75 months old, most studies in-cluded children 2 to 4 years old, and their results do notallow for determination of the optimal ages of interven-tion.

The studies evaluated the effects of individual orgroup therapy directed by clinicians and/or parents thatfocused on specific speech and language domains. Thesedomains included expressive and receptive language,articulation, phonology, lexical acquisition, and syntax.Several studies used established approaches to therapysuch as the Ward Infant Language Screening Test, As-sessment, Acceleration, and Remediation program96 andthe Hanen principles.78,79,85,93 Others used more theoret-ical approaches such as focused stimulation,78,79,86,87,93 au-ditory discrimination,83,90 imitation or modeling proce-dures,76,92 auditory processing or work mapping,85 andplay narrative language.80,81 Some interventions focusedon specific words and sounds, used unconventionalmethods, or targeted a specific deficit.

Outcomes were measured by subjective reports fromparents77,78,80,85 and by scores on standardized instru-ments such as the Reynell Expressive and ReceptiveScales,74,77 the Preschool Language Scale,72,75,85 and theMacArthur Communicative Development Invento-ries.80,93 The most widely used outcome measure wasmean-length utterances, used by 6 studies.73,75,77,80,85

Studies rated as good or fair quality are describedbelow by age categories according to the youngest agesincluded, although many studies included children inoverlapping categories

Ages 0 to 2 YearsNo studies examined this age group exclusively, al-though 1 good-quality study enrolled children who were18 to 42 months old.72 The clinician-directed, 12-monthintervention consisted of 10-minute weekly sessions fo-cusing on multiple language domains, expressive andreceptive language, and phonology. Treatment for re-ceptive auditory comprehension lead to significant im-provement for the intervention group compared withthe control group; however, results did not differ be-tween groups for several expressive and phonology out-comes.72

Ages 2 to 3 YearsOne good72 and 6 fair-quality77–80,84,85 studies evaluatedspeech and language interventions for children who

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e309 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

were 2 to 3 years old. The studies reported improvementon a variety of communication domains including clini-cian-directed treatment for expressive and receptive lan-guage,80 parent-directed therapy for expressive delay,77,78

and clinician-directed receptive auditory comprehen-sion.72 Lexical acquisition was improved with both clini-cian-directed84,91 and group therapy approaches.84 In 3studies, there were no between-group differences forclinician-directed expressive72,85 or receptive languagetherapy,72,85 parent-directed expressive or receptive ther-apy,85 or parent-directed phonology treatment.79

Ages 3 to 5 YearsFive fair-quality studies reported significant improve-ments for children who were 3 to 5 years old and un-dergoing interventions compared with controls,73,74,76,81,82

whereas 2 studies reported no differences.75,83 Bothgroup-based81 and clinician-directed74 interventionswere successful in improving expressive and receptivecompetencies.

Systematic ReviewA Cochrane systematic review included a meta-analysisusing data from 25 RCTs of interventions for speech andlanguage delay for children up to adolescence.35 Twenty-three of these studies72–92,95 also met criteria for this re-view and are included in Table 7, and 2 trials wereunpublished. The review reported results in terms ofstandard mean differences (SMDs) in scores for a num-ber of domains (phonology, syntax, and vocabulary).Effectiveness was considered significant for both thephonological (SMD: 0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI]:0.01–0.86) and vocabulary (SMD: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.21–1.56) interventions. Less effective was the receptive in-tervention (SMD: �0.04; 95% CI: 0.64–0.56), and re-sults were mixed for the expressive syntax intervention(SMD: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.04–2.01). When interventionswere comparable in duration and intensity, there wereno differences between interventions when they wereadministered by trained parents or clinicians for expres-sive delays. Use of normal-language peers as part of theintervention strategy also proved beneficial.81

Key Question 6: Do Interventions for Speech and LanguageDelay Improve Other Non–Speech and Language Outcomes?Four good-72 or fair-quality80,81,85 intervention studies in-cluded functional outcomes other than speech and lan-guage. Increased toddler socialization skills,80 improvedchild self-esteem,85 and improved play themes81 werereported for children in intervention groups in 3 studies.Improved parent-related functional outcomes includeddecreased stress80 and increased positive feelings towardtheir children.85 Functional outcomes that were studiedbut did not show significant treatment effects includedwell-being, levels of play and attention, and socializationskills in 1 study.72TA

BLE6

Stud

iesof

Screen

ingInstrumen

tsforC

hildren3to

5Ye

arsOld

Authors(y)

NInstrument

ReferenceStandard

Speech

andLang

uage

Dom

ains

Subjects

Setting

Screener

Sensitivity,%

Specificity,%

Stud

yQuality

Ratin

g

�10

mintoadminister

AllenandBliss

69

(1987)

182

FluhartyPreschoolSpeech

andLanguage

ScreeningTest

SequencedInventoryof

Communication

Development

Expressiveandreceptive

language,articulation

From

daycare

programs;36–47mo

Clinic

Speech

andlanguage

pathologists

6080

Fair

Sturneretal71(1996)

76Sentence

Repetition

ScreeningTest

Speech

andLanguage

ScreeningQuestionnaire

Receptiveand

expressivelanguage,

articulation

Childrenregisteringfor

kindergarten;48%

male;65%white;

54–66mo

School

Nonspecialistsorschool

speech

andlanguage

pathologists

62(receptiveand

expressive);57

(articulation)

91(receptiveand

expressive);95

(articulation)

Fair

MerrellandPlante

70

(1997)

40TestforExamining

ExpressiveMorphology

Kaufman

AssessmentBattery

forChildren,Structured

PhotographicExpressio

nLanguage

TestII

Expressivevocabulary,

syntax

20impairedand20

unimpaired;52%

male73%white;

48–67mo

Schoolorclinic

Speech

andlanguage

pathologists

9095

Poor

e310 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

TABLE7

RCTs

ofInterven

tion

s

Authors(y)

Speech

andLang

uage

Dom

ains

N(No.of

Group

s)Ag

e,mo

Interventio

nsSpeech

andLang

uage

Outcomes

Functio

nandHealth

Outcomes

Stud

yQuality

Ratin

g

Upto2ya

Glogow

skaetal72

(2000)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

andphonology

159(2)

18–42

Clinician-directed

individual

intervention,routinely

offeredby

thetherapist

for12mo,vsnone

Improved

auditorycomprehensio

nin

interventionvscontrolgroup;no

differencesforexpressive

language,phonology

errorrate,

language

developm

ent,or

improvem

entonentry

criterion

Nodifferencesinwell-being,

attentionlevel,play

level,

orsocializationskills

Good

2to3y

Gibbard7

7(1994)

Study1

Expressivelanguage

36(2)

27–39

Parent-directed

individual

therapyfor60–75

min

everyotherw

eekfor6

movsnone

Improved

scoreson

severalm

easures

forinterventionvscontrolgroup

Notreported

Fair

Girolamettoet

al78(1996)

Expressivelanguage

25(2)

23–33

Parent-directed

individual

focusedstimulation

interventionfor150

min/

wkfor11wkvsnone

Largervocabularies,useofmore

differentwords,m

orestructurally

completeutterancesand

multiw

ordutterancesin

interventiongroupvscontrol;no

differencesinseveralother

measures

Notreported

Fair

Lawetal85(1999)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

38(3)

33–39

Clinician-directed

for450

min/wkfor6

wkvs

parent-directed

for150

min/wkfor10wkvs

none

Nodifferencesbetweengroups

Improved

parentperception

ofchild’sbehaviorand

positivity

towardchild,

improved

child

self-

esteem

Fair

Robertson

and

Weism

er80

(1999)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

21(2)

21–30

Clinician-directed

individual

therapy150min/wkfor

12wkvsnone

Improved

meanlengthofutterances,

totalnum

berofw

ords,lexical

diversity,vocabularysize,and

percentage

ofintelligible

utterancesininterventiongroupvs

control

Improved

socializationskills,

decreasedparentalstress

forinterventiongroup

Fair

Gibbard7

7(1994)

Study2

Expressivelanguage

25(3)

27–39

Clinician-directed

individual

therapyfor60–75

min

everyotherw

eekfor6

movsparent-directed

for

60–75mineveryother

weekfor6

movsnone

Improved

scoreson

all5

measuresfor

parent-directed

groupvscontrol;

improvem

enton2measuresfor

clinician-directed

groupvscontrol;

improvem

enton1measurefor

parentvscliniciangroup

Notreported

Poor

Girolamettoet

al93(1996)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

16(2)

22–38

Parent-directed

individual

therapyfor150

min/wk

for10wkvsnone

Moretargetwords

used

ininterventiongroupvscontrol;no

differencesinvocabulary

developm

ent

Increasedsymbolicplay

gestures,decreased

aggressivebehaviorin

interventiongroup

Poor

Schw

artzetal91

(1985)

Expressivelanguage

and

lexicalacquisition

10(2)

32–39

Clinician-directed

individual

therapyfor3

wkvsnone

Improved

multiw

ordutterancesfrom

baselineininterventiongroup;no

between-groupdifferences

reported

Notreported

Poor

Wilcox

etal84

(1991)

Lexicalacquisition

20(2)

20–47

Clinician-directed

individual

interventionfor90min/

Nodifferencesbetweengroups

inuseoftargetwords;m

oreuseof

Notreported

Fair

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e311 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

TABLE7

Continue

d

Authors(y)

Speech

andLang

uage

Dom

ains

N(No.of

Group

s)Ag

e,mo

Interventio

nsSpeech

andLang

uage

Outcomes

Functio

nandHealth

Outcomes

Stud

yQuality

Ratin

g

wkfor3

movsclassroom

interventionfor360

min/

wkfor3

mo

words

athomeinclassroomgroup

vsindividualgroup

Girolamettoet

al79(1997)

Lexicalacquisitionand

phonology

25(2)

23–33

Parent-directed

individual

therapyforeight150-

minsessions

and3home

sessions

for11wkvs

none

Improved

levelofvocalizations

and

inventoryofconsonantsfor

interventiongroupvscontrol;no

differencesinthenumberof

vocalizations

Notreported

Fair

3to5y

Barrattetal74

(1992)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

39(2)

37–43

Clinician-directed

interactivelanguage

therapyfor40min/wk

for6

mo(traditional

group)vs40

minfor4

days/wkfor3

wkintwo

3-moblocks(intensive

group)

Improved

expressio

nscoreon

Reynellscaleforintensivegroupvs

weekly(ortraditional)therapy

group;no

differencein

comprehensio

nscores,bothwere

improved

Notreported

Fair

Courtrightand

Courtright76

(1979)

Expressivelanguage

36(3)

47–83

3clinician-directed

approachesare

comparedfor5

mo:

mimicry,clinician

modeling,3rd-person

modelingfor5

mo

Increasednumberofcorrect

responsesinmodelinggroups

vsmimicrygroup

Notreported

Fair

Robertson

and

Weism

er81

(1997)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

30(3)

44–61

2clinician-directed

play

groups

with

language

impairm

ents(treatm

ent

vscontrol)with

norm

alpeersfor20

min/wkfor3

wk

Morewords

used,greaterverbal

productivity,m

orelexicaldiversity,

andmoreuseoflinguisticmarkers

bynorm

alpeerplay

group(not

norm

algroup,treatmentgroup

with

language

impairm

ent)vs

control

Play-theme–relatedacts

increasedforthe

norm

alpeerplay

group(not

norm

algroup,treatment

groupwith

language

impairm

ent)

Fair

Glogow

skaetal72

(2002)

Expressiveandreceptive

language

and

phonology

159(2)

�42

Clinician-directed

for12mo

vsnone

Improved

receptivelanguage

ininterventiongroupvscontrol;no

differencesbetweengroups

for4

otherm

easures

Improved

familyresponseto

child

inintervention

group

Poor

Almostand

Rosenbaum

73

(1998)

Phonology

26(2)

33–61

Clinician-directed

individual

therapyfortwo30-m

insessions/wkfor4

movs

none

Higherscoreso

n3of4measuresfor

interventionvscontrolgroup

Notreported

Fair

Rvachewand

Now

ak82(2001)

Phonology

48(2)

50(m

ean)

Clinician-directed

individual

therapy30–40min/wk

for12wk;compares

interventions

for

phonem

esthatdiffer

(most-know

ledge/early-

developing

groupvs

Improved

scoreson

measuresfrom

baselineforbothintervention

groups;greaterimprovem

entfor

most-know

ledge/early-

developing

phonem

esgroupvs

comparison

(least-know

ledge/

latest-developing)group

Notreported

Fair

e312 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

least-know

ledge/latest-

developing

group)

Sheltonetal83

(1978)

Phonologyand

articulation

45(3)

27–55

Parent-directed

individual

therapyfor5

minperday

(listeninggroup)vs15

Noimprovem

entsforintervention

groups

vscontrol

Notreported

Fair

minperday

(readingand

talkinggroup)for57days

vsnone

Feyetal86(1994)

Phonologyandsyntax

26(3)

44–70

Clinician-directed

sessions

(individualandgroup)for

3h/wkfor20wkvs

parent-directed

sessions

for8

h/wkforw

eeks1–

12(includesintensive

parenttraining)then

4h/wkforw

eeks13–20vs

none

Improved

gram

maticaloutput

(developmentalsentencescores)

forbothinterventiongroups

vscontrol;no

significantdifference

betweengroups

forphonological

output(percentageconsonants

correct)

Notreported

Poor

Reidand

Donaldson

95

(1996)

Phonology

30(2)

42–66

Clinician-directed

individual

therapyfor30min/wkfor

6–10

wkvsnone

Improved

scoreson

somemeasures

frombaselineforinterventionand

controlgroups;no

between-group

comparisonsreported

Notreported

Poor

Ruscelloetal89

(1993)

Phonology

12(2)

49–68

Clinician-directed

vsclinician-andparent-

directed

individual

therapyfor120

min/wk

for8

wk

Improved

scoreson

measuresfrom

baselineforbothintervention

groups;nobetween-group

comparisonsreported

Notreported

Poor

Rvachew

90(1994)

Phonology

27(3)

42–66

Clinician-directed

individual

therapyfor45min/wkfor

6wk;compares3

groups

listening

todifferentsets

ofwords

Improved

scoreson

measuresfor2

interventiongroups

vsthird

group

Notreported

Poor

ColeandDale7

5

(1986)

Syntax

44(2)

38–69

Clinician-directed

individual

directiveapproach

vsinteractiveapproach

for

600min/wkfor8

mo

Improved

scoreson

6of7measures

frombaselineforbothintervention

groups;nosig

nificantdifferences

betweengroups

Notreported

Fair

Feyetal92(1993),

firstphase

Syntax

29(3)

44–70

Clinician-directed

sessions

(individualandgroup)for

3h/wkfor20wkvs

parent-directed

sessions

for8

h/wkforw

eeks1–

12(includesintensive

parenttraining)then

4h/wkforw

eeks13–20vs

none

Improved

scoreson

3of4measures

forbothinterventiongroups

vscontrol;no

differencesbetween

interventiongroups

Notreported

Poor

Feyetal87(1997),

second

phase

Syntax

28(3)

44–70

Clinician-directed

vsparent-

directed

vsnone

for5

mo

continuing

fromprior

study

Improved

somedevelopm

ental

sentence

scoresfrombaselinein

bothinterventiongroups

vscontrol;no

between-group

comparisonsreportedexceptthat

Notreported

Poor

PEDIATRICS Volume 117, Number 2, February 2006 e313 by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

Key Question 7: Does Improvement in Speech and LanguageOutcomes Lead to Improved Additional Outcomes?No studies addressed this question.

Key Question 8: What Are the Adverse Effects ofInterventions?No studies addressed this question. Potential adverseeffects of treatment programs include the impact of timeand cost of interventions on clinicians, parents, children,and siblings. Loss of time for play and family activities,stigmatization, and labeling may also be potential ad-verse effects.

CONCLUSIONSStudies are not available that address the overarchingkey question about the effectiveness of screening (keyquestion 1), adverse effects of screening (key question3), the role of enhanced surveillance in primary care(key question 4), long-term effectiveness of interven-tions on non–speech and language outcomes for chil-dren identified with delay (key question 7), and adverseeffects of interventions (key question 8). No studies havedetermined the optimal ages and frequency for screen-ing (key question 2d). Relevant studies are availableregarding the use of risk factors for screening (key ques-tion 2a), techniques for screening (key questions 2b and2c), and effectiveness of interventions on short-termspeech and language and non–speech and language out-comes for children identified with delay (key questions 5and 6).

The use of risk factors for selective screening has notbeen evaluated, and a list of specific risk factors to guideprimary care physicians has not been developed ortested. Sixteen studies about potential risk factors forspeech and language delay in children enrolled hetero-geneous populations, had dissimilar inclusion and exclu-sion criteria, and measured different risk factors andoutcomes. The most consistently reported risk factorsincluded a family history of speech and language delay,male gender, and perinatal factors. Other risk factorsthat were reported less consistently include educationallevels of the mother and father, childhood illnesses, birthorder, and family size.

Although brief evaluations are available and havebeen used in a number of settings with administration byprofessional and nonprofessional individuals, includingparents, the optimal method of screening for speech andlanguage delay has not been established. The perfor-mance characteristics of evaluation techniques that take�10 minutes to administer were described in 24 studiesthat were relevant to screening. The studies that wererated as good to fair quality reported wide ranges ofsensitivity and specificity when compared with referencestandards (sensitivity: 17–100%; specificity: 45–100%).In these studies, the instruments that provided the high-est sensitivity and specificity included the Early Lan-TA

BLE7

Continue

d

Authors(y)

Speech

andLang

uage

Dom

ains

N(No.of

Group

s)Ag

e,mo

Interventio

nsSpeech

andLang

uage

Outcomes

Functio

nandHealth

Outcomes

Stud

yQuality

Ratin

g

clinician-directed

treatment

groups

hadlargerandmore

consistentgains

than

parent-

directed

treatmentgroupso

rcontrol

Mulac

and

Tomlinson8

8

(1977)

Syntax

9(3)

52–75

Clinician-directed

individual

Monteraylanguage

programvsMonteray

language

programwith

extended

transfer

trainingfor67min/wk

for4

wkvsnone

Improved

scoresforboth

interventiongroups

vscontrol;no

significantdifferencesb

etween

interventiongroups

Notreported

Poor

aStudiesw

itharangeofagesarenotrepeatedacrosscategories.

e314 NELSON, et al by guest on June 9, 2018www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

guage Milestone Scale, Clinical Linguistic and AuditoryMilestone Scale, Language Development Survey,Screening Kit of Language Development, and the Levett-Muir Language Screening Test. Most of the evaluations,however, were not designed for screening purposes, theinstruments measured different domains, and the studypopulations and settings were often outside primarycare. No gold standard has been developed and tested forscreening, reference standards varied across studies, fewstudies compared the performance of �2 screening tech-niques in 1 population, and comparisons of a singlescreening technique across different populations arelacking.

RCTs of multiple types of interventions reported sig-nificantly improved speech and language outcomescompared with control groups. Improvement was dem-onstrated in several domains including articulation, pho-nology, expressive language, receptive language, lexicalacquisition, and syntax among children in all age groupsstudied and across multiple therapeutic settings. How-ever, studies were small and heterogeneous, may besubject to plateau effects, and reported short-term out-comes based on various instruments and measures. As aresult, long-term outcomes are not known, interven-tions could not be directly compared to determine opti-mal approaches, and generalizability is questionable.

There are many limitations of the literature relevantto screening for speech and language delay in preschool-aged children, including a lack of studies specific toscreening as well as difficulties inherent in this area ofresearch. This evidence review is limited by the use ofonly published studies of instruments and interventions.Data about performance characteristics of instruments,in particular, are not generally accessible and are oftenonly available in manuals that must be purchased. In-terventions vary widely and may not be generalizable. Inaddition, studies from countries with different healthcare systems, such as the United Kingdom, may nottranslate well to US practice.

Although speech and language development is mul-tidimensional, the individual constructs that comprise itare often assessed separately. Numerous evaluation in-struments and interventions that accommodate childrenacross a wide range of developmental stages have beendeveloped to identify and treat specific abnormalities ofthese functions. As a result, studies include many differ-ent instruments and interventions that most often aredesigned for purposes other than screening. Also, studiesof interventions typically focus on 1 or a few interven-tions. In clinical practice, children are provided withindividualized therapies consisting of multiple interven-tions. The effectiveness of these complex interventionsmay be difficult to evaluate. Adapting the results of thisheterogeneous literature to determine benefits and ad-verse effects of screening is problematic. Also, behavioralinterventions are difficult to conduct in long-term ran-

domized trials, and it is not possible to blind parents orclinicians. Randomly assigning children to therapy orcontrol groups when clinical practice standards supporttherapy raises ethical dilemmas.

Speech and language delay is defined by measure-ments on diagnostic instruments in terms of a positionon a normal distribution. Measures and terminology areused inconsistently, and there is no recognized goldstandard. This is challenging when defining cases anddetermining performance characteristics of screening in-struments in studies.

Identification of speech and language delay may beassociated with benefits and adverse effects that wouldnot be captured by studies of clinical or health outcomes.The process of screening alerts physicians and caretakersto developmental milestones and focuses attention onthe child’s development, potentially leading to increasedsurveillance, feelings of caregiver support, and improvedchild self-esteem. Alternatively, caretakers and childrenmay experience increased anxiety and stress during thescreening and evaluation process. Detection of otherconditions during the course of speech and languageevaluation, such as hearing loss, is an unmeasured ben-efit if appropriate interventions can improve the child’sstatus.