SAGIR Bilan 2006 2007 2008 final-anglais Results from 2006 to 2008.pdf · IV.A NEW PATHOGENS AND...

Transcript of SAGIR Bilan 2006 2007 2008 final-anglais Results from 2006 to 2008.pdf · IV.A NEW PATHOGENS AND...

Wildlife epidemiological surveillance ‐

Results of analyses performed from 2006 to 2008 within the framework of the SAGIR network

Anouk Decors, Olivier Mastain Translation by Catherine Carter

National hunting and wildlife agency (ONCFS) Department of studies and research

Edition July 2010

2

Suggested citation :

Decors A., Mastain O., 2010, Wildlife epidemiological surveillance, results of analyses performed from 2006 to 2008 within the framework of the SAGIR network, ONCFS/FNC/FDC network. National hunting and wildlife agency (ONCFS) (ed.), Paris, 48p. http://www.oncfs.gouv.fr/Reseau‐SAGIR‐ru105

3Epidémiosurveillance de la faune sauvage – Bilan des analyses effectuées de 2006 à 2008 dans le cadre du réseau SAGIR. Juillet 2010. Pour toute utilisation de ces données, en particulier à des fins scientifiques, merci de prendre contact avec le réseau [email protected]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................7

I METHODS ..........................................................................................................................................................8 I.A EPIDEMIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SAGIR NETWORK .............................................................................8 I.B DEFINITION OF THE CASE..........................................................................................................................................8 I.C INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS..................................................................................................................................8

II SPATIO‐TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CASES FROM 2006 TO 2008......................................................................9 II.A ANNUAL DISTRIBUTION OF CASES............................................................................................................................9 II.B MONTHLY DISTRIBUTION OF CASES .......................................................................................................................10 II.C DISTRIBUTION OF CASES PER MUNICIPALITY .........................................................................................................12

III SAMPLE DESCRIPTION ...................................................................................................................................... 14 III.A SPECIES ...................................................................................................................................................................14 III.B DEAD ANIMALS VS. SICK ANIMALS .........................................................................................................................16

IV MAIN INFECTIOUS AND PARASITIC DISEASES DIAGNOSED BETWEEN 2006 AND 2008 ...................................... 16 IV.A NEW PATHOGENS AND DISEASES IDENTIFIED BETWEEN 2006 AND 2008 .............................................................16 IV.B DISEASES WITH AN IMPACT ON WILDLIFE SPECIES’ POPULATIONS OBSERVED BETWEEN 2006 AND 2008 ..........17

IV.B.1 Species whose hunting is authorized, key events .....................................................................................................17 IV.B.1.1 Wood pigeon................................................................................................................................................................. 17 IV.B.1.2 Stock dove ..................................................................................................................................................................... 17 IV.B.1.3 Collared dove ................................................................................................................................................................ 18 IV.B.1.4 European rabbit ............................................................................................................................................................ 18 IV.B.1.5 Roe deer ........................................................................................................................................................................ 18 IV.B.1.6 Chamois ........................................................................................................................................................................ 18 IV.B.1.7 Red fox .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 IV.B.1.8 European brown hare.................................................................................................................................................... 18 IV.B.1.8.1 Dominant pathological features............................................................................................................................. 18 IV.B.1.8.2 Zoom on European brown hare syndrome (EBHS) ................................................................................................. 20

IV.B.1.8.2.1 EBHS macroscopic findings................................................................................................................ 20 IV.B.1.8.2.2 Distribution of cases per departement from 2005 to 2008 ............................................................... 22

IV.B.2 Protected species, key events...................................................................................................................................23 IV.B.2.1 Alpine ibex..................................................................................................................................................................... 23 IV.B.2.2 Brent goose ................................................................................................................................................................... 24 IV.B.2.3 Red squirrel ................................................................................................................................................................... 24 IV.B.2.4 Gulls .............................................................................................................................................................................. 24 IV.B.2.5 Black‐headed gull .......................................................................................................................................................... 24 IV.B.2.6 Siskin ............................................................................................................................................................................. 24 IV.B.2.7 Greenfinch..................................................................................................................................................................... 25

IV.C ZOONOTIC PATHOGENS IDENTIFIED BETWEEN 2006 AND 2008 ...........................................................................25 IV.C.1 Tularemia ..................................................................................................................................................................25 IV.C.2 Swine erysipelas........................................................................................................................................................25 IV.C.3 Leptospirosis .............................................................................................................................................................25 IV.C.4 Pseudotuberculosis...................................................................................................................................................25

IV.D PATHOGENS SHARED WITH DOMESTIC ANIMALS IDENTIFIED BETWEEN 2006 AND 2008 ....................................26

V INTOXICATIONS IDENTIFIED BY SAGIR FROM 2006 TO 2008.............................................................................. 26 V.A IDENTIFIED CAUSATIVE AGENTS OF INTOXICATIONS .............................................................................................26

V.A.1 Intoxications by anticoagulants from 2006 to 2008.................................................................................................29 V.A.2 Intoxications by cholinesterase inhibitors from 2006 to 2008.................................................................................30 V.A.3 Intoxications by organochlorines from 2006 to 2008 ...............................................................................................31 V.A.4 Intoxications by chloralose from 2006 to 2008.........................................................................................................31 V.A.5 Intoxications by toxicant associations from 2006 to 2008........................................................................................33

V.B DISTRIBUTION PER DEPARTEMENT OF INTOXICATION CASES FROM 2006 TO 2008..............................................34 V.C INTENTIONAL INTOXICATION .................................................................................................................................34

VI EXAMPLES OF COMPLEMENTARY SAGIR EPIDEMIOLOGICAL MONITORING PROGRAMMES ............................... 35 VI.A MONITORING OF INFLUENZA VIRUSES IN THE WILD AVIFAUNA............................................................................35 VI.B MONITORING OF THE WEST‐NILE VIRUS IN THE WILD AVIFAUNA .........................................................................36 VI.C SAGIR, AN ESSENTIAL LINK FOR THE MONITORING OF CLASSICAL SWINE FEVER ..................................................37 VI.D MONITORING OF TUBERCULOSIS IN WILD ANIMALS IN FRANCE ...........................................................................38 VI.E AVIAN SCHISTOSOMA : BIODIVERSITY, HOST – PARASITE RELATIONSHIPS, IMPLICATIONS IN CERCARIAL

DERMATITIS ............................................................................................................................................................39

CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................................................................................... 41

VII REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................................................... 43

4Epidémiosurveillance de la faune sauvage – Bilan des analyses effectuées de 2006 à 2008 dans le cadre du réseau SAGIR. Juillet 2010. Pour toute utilisation de ces données, en particulier à des fins scientifiques, merci de prendre contact avec le réseau [email protected]

TABLES AND FIGURES Figure 1 : Number of cases recorded from 2005 to 2008 by the SAGIR network....................................................................................9 Figure 2 : Monthly distribution of cases in 2006, 2007, 2008................................................................................................................11 Figure 3 : Monthly distribution of roe deer cases in 2006, 2007, 2008. ................................................................................................12 Figure 4 : Monthly distribution of European brown hare cases in 2006, 2007, 2008...........................................................................12 Figure 5 : Distribution of cases per municipality in metropolitan France and in Martinique in 2006, 2007 and 2008..........................13 Figure 6 : Ranking of species in the SAGIR sample sinced 1986 according to the number of cases .....................................................14 Figure 7 : Species richness of the SAGIR sample in 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 ...................................................................................15 Figure 8 : Monthly distribution of cases in 2006 for the common buzzard, starling, grey heron, blackbird, house sparrow, siskin,

collared dove and greenfinch. ..............................................................................................................................................15 Figure 9 : Dominant pathological features in the European brown hare – Relative evolution between 2005 and 2008.....................19 Figure 10 : Cumulated presence and distribution per departement of pasteurellosis in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008.

..............................................................................................................................................................................................19 Figure 11 : Frequency of lesions associated with EBHS in the European brown hare between 2006 and 2008 ...................................20 Figure 12 : Frequency of affected organs in EBHS cases in the European brown hare between 2006 and 2008..................................21 Figure 13 : Representation of the principal lesion/organ associations in EBHS cases in the European brown hare from 2006 to 2008.

..............................................................................................................................................................................................21 Figure 14 : Classification of lesion associations most frequently described in EBHS cases in the European brown hare between 2006

and 2008...............................................................................................................................................................................22 Figure 15 : Cumulated presence and distripution per departement of EBHS in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008. .........23 Figure 16 : Cumulated presence and distribution per departement of tularemia in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008. .25 Figure 17 : Cumulated presence and distribution per departement of pseudotuberculosis in the European brown hare from 2005 to

2008......................................................................................................................................................................................26 Figure 18 : Departements concerned by anticoagulant intoxications from 2006 to 2008....................................................................30 Figure 19 : Proportion of chloralose intoxications among confirmed intoxication cases in wild birds..................................................32 Figure 20 : Weekly distribution of chloralose intoxication cases in wild birds in France and highly pathogenic avian influenza cases

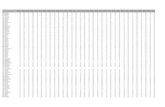

in Europe in 2006 .................................................................................................................................................................33 Figure 21 : Number of intoxication cases per departement from 2006 to 2008 identified by SAGIR....................................................34 Table I : The 7 most represented species in the database in 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008. ...................................................................16 Table II : List of the new pathogens and diseases identified by SAGIR between 2006 and 2008. ........................................................17 Table III : Toxicants quantified per species and per year from 2006 to 2008........................................................................................27 Table IV : Number of anticoagulant intoxication cases per species from 2006 to 2008........................................................................29 Table V : Number of cholinesterase inhibitor intoxication cases per species from 2006 to 2008. ......................................................30 Table VI : Number of organochlorine intoxication cases per species from 2006 to 2008. ....................................................................31 Table VII : Number of individuals per species, intoxicated by chloralose in 2006. ................................................................................31 Table VIII : Toxicant associations and species concerned.....................................................................................................................33 Table IX : Number of individuals per species intoxicated intentionally from 2006 to 2008. .................................................................35 Table IX : Observed prevalences of avian schistosoma in 16 bird species according to the visceral or nasal localization of parasites 39

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ADILVA : French association of directors and managers of public veterinary laboratories

ANSES : French agency for food, environmental and occupational health safety

CSF: Classical swine fever

DDD : dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane

DR : Interregional delegation of the ONCFS

EBHS : European brown hare syndrom

FDC : Departemental hunting federation

FNC : National hunting federation

FRC : Regional hunting federation

H5N1 HP : Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1

ITD : Technical departemental representative

LDAV : Departemental veterinary laboratory

MAC : Abnormal roe deer mortality

ONCFS : National hunting and wildlife agency

PCB : Polychlorobiphenyles

SAGIR : The term SAGIR was created by Claude Mallet, first national manager of the network. SAGIR is not an acronym, but rather sounds like a motto, SAGIR, surveiller pour agir !

SD : Departemental service of the ONCFS

WN : West‐Nile

5Epidémiosurveillance de la faune sauvage – Bilan des analyses effectuées de 2006 à 2008 dans le cadre du réseau SAGIR. Juillet 2010. Pour toute utilisation de ces données, en particulier à des fins scientifiques, merci de prendre contact avec le réseau [email protected]

FOREWORD

I am pleased to present you the results of analyses performed within the framework of the SAGIR network during the years 2006, 2007 and 2008.

In 2006, and to a lesser extent in 2007, the network was mobilized in the participation to the management of health crises related to the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1. All the network’s organisation levels were involved. The observers, the technical departemental representatives (ITD), the technicians and veterinarians of the departemental veterinary laboratories, managed the inflow of notifications and analyses. But this resourcefulness has also shown its limitations at the data centralization and processing level. This explains the delay in the exploitation of results and in the production of this special report covering three years of monitoring.

These results rely on an exceptional network, both in its human dimensions with its regular collaborations and in its technical and scientific achievements at an unequalled geographical scale. They provide invaluable information to hunters, hunting managers, biologists, epidemiologists, public policy makers and the general public.

This is the occasion to express my deep gratitude to all the people, Presidents, administrators, staff and ITD of the departemental, regional and national hunting federations, hunters and naturalists, agents and ITD of the ONCFS, staff of the departemental veterinary laboratories, the other laboratory partners of SAGIR and the rabies and wildlife laboratory of ANSES in Nancy, Presidents and local councillors, officials of the Ministry of the Environment, who daily participate to the surveillance of wildlife diseases in a direct and practical way or by investing their own means, for a sustainable hunting and the protection of wild birds and mammals.

I hope this report will inform and interest you. You will find a satisfaction questionnaire at the end of this report, which I invite you to fill in with comments and suggestions so as to make the next report of analyses performed in 2009 a document satisfying all ambitions.

Lastly, I invite you to disseminate this report around you. It is available in French and in English, on the Internet pages of the SAGIR network www.oncfs.gouv.fr/Reseau‐SAGIR‐ru105. Administrator and scientific manager of the SAGIR

network

Olivier MASTAIN

6Epidémiosurveillance de la faune sauvage – Bilan des analyses effectuées de 2006 à 2008 dans le cadre du réseau SAGIR. Juillet 2010. Pour toute utilisation de ces données, en particulier à des fins scientifiques, merci de prendre contact avec le réseau [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Philippe Aubry (ONCFS), Philippe Berny (veterinary VetAgro Sup Campus of Lyon), Catherine Carter (ONCFS), Charlotte Dunoyer (FNC), Hubert Ferté (University of Reims Champagne‐Ardenne), Dominique Gauthier (ADILVA), Sophie Grammont (ONCFS), Jean‐Sébastien Guitton (ONCFS), Jean Hars (ONCFS), Philippe Landry (ONCFS), Marie Moinet (ANSES), Viviane Moquay‐Tkaczuk (ADILVA), Sophie Rossi (ONCFS) and Alain VIRY (LDAV du Jura) for their careful reading and their contribution to this report.

The SAGIR network is grateful to all the observers, in particular the hunters and technicians of the ONCFS who relentlessly submit their observations, for the knowledge, hunting management and environmental protection.

The SAGIR network sincerely thanks all the actors of the network for their contribution :

The hunters and naturalists, the veterinary practitioners at their side ;

The national, regional and departemental hunting federations, FNC, FRC Alsace, FRC Auvergne, FRC Bourgogne, FRC Centre, FRC Corse, FRC Haute‐Normandie, FRC Languedoc‐Roussillon, FRC Lorraine, FRC Nord Pas‐de‐Calais, FRC Picardie, FRC Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, FRC Rhône‐Alpes, FRC Poitou‐Charentes, FRC Pays‐de‐la‐Loire, FRC Midi‐Pyrénées, FRC Limousin, FRC Ile‐de‐France, FRC Franche‐Comté, FRC Champagne‐Ardenne, FRC Bretagne, FRC Basse‐Normandie, FRC Aquitaine, FDC 01,FDC 02, FDC 03, FDC 04, FDC 05, FDC 06, FDC 07, FDC 08, FDC 09, FDC 10, FDC 11, FDC 12, FDC 13, FDC 14, FDC 15, FDC 16, FDC 17, FDC 18, FDC 19, FDC 2A, FDC 2B, FDC 21, FDC 22, FDC 23, FDC 24, FDC 25, FDC 26, FDC 27, FDC 28, FDC 29, FDC 30, FDC 31, FDC 32, FDC 33, FDC 34, FDC 35, FDC 36, FDC 37, FDC 38, FDC 39, FDC 40, FDC 41, FDC 42, FDC 43, FDC 44, FDC 45, FDC 46, FDC 47, FDC 48, FDC 49, FDC 50, FDC 51, FDC 52, FDC 53, FDC 54, FDC 55, FDC 56, FDC 57, FDC 58, FDC 59, FDC 60, FDC 61, FDC 62, FDC 63, FDC 64,FDC 65, FDC 66, FDC 67, FDC 68, FDC 69, FDC 70, FDC 71, FDC 72, FDC 73, FDC 74, FDC 75, FDC 76, FDC 77, FDC 78, FDC 79, FDC 80, FDC 81, FDC 82, FDC 83, FDC 84, FDC 85, FDC 86, FDC 87, FDC 88, FDC 89, FDC 90, FDC 972 and in particular the technical departemental representatives ;

The interregional delegations and departemental services of the National hunting and wildlife agency (ONCFS), DR Alpes Méditerranée – Corse, DR Bretagne Pays de la Loire, DR Nord‐Ouest, DR Nord‐Est, DR Poitou‐Charente Limousin, DR Bourgogne Franche‐Comte, DR Sud‐Ouest, DR Auvergne Languedoc‐Roussillon, DR Centre Ile‐de‐France, SD 01, SD 02, SD 03, SD 04, SD 05, SD 06, SD 07, SD 08, SD 09, SD 10, SD 11, SD 12, SD 13, SD 14, SD 15, SD 16, SD 17, SD 18, SD 19, SD 2A, SD 2B, SD 21, SD 22, SD 23, SD 24, SD 25, SD 26, SD 27, SD 28, SD 29, SD 30, SD 31, SD 32, SD 33, SD 34, SD 35, SD 36, SD 37, SD 38, SD 39 ,SD 40, SD 41, SD 42, SD 43, SD 44, SD 45, SD 46, SD 47, SD 48, SD 49, SD 50, SD 51, SD 52, SD 53, SD 54, SD 55, SD 56, SD 57, SD 58, SD 59, SD 60, SD 61, SD 62, SD 63, SD 64, SD 65, SD 66, SD 67, SD 68, SD 69, SD 70, SD 71, SD 72, SD 73, SD 74, SD 75, SD 76, SD 77, SD 78, SD 79, SD 80, SD 81, SD 82, SD 83, SD 84, SD 85, SD 86, SD 87, SD 88, SD 89, SD 90, SD972 and in particular the technical departemental representatives ;

The departemental veterinary laboratories and the “Conseils généraux”, LDA 01, LVD 02, LVD 03, LVD 04, LVD 05, LVD 06, LDA 08, LVD 09, LDA 10, LVD 11, Aveyron Labo, LDA 13, Laboratoire départemental Franck Duncombe, LASAT, LDA 18, LDA 19, Laboratoire départemental d'analyses vétérinaires, agricoles et des eaux d'Ajaccio, LDA 2B, LDA 21, Laboratoire de développement et d'analyse de Ploufragan, LDA 23, LDA 24, LVD 25, LDA 26, LDA 27, IDHESA Bretagne – Océane, LDA 30, LVD 31, LVD 32, LABSA 33, LVD 34, Institut en santé Agro ‐ environnement 35, LDA 36, LDA 37, LVD 38, LDA 39, LDA 40, LVD 42, LDA 43, Institut départemental d'analyses et conseil de Nantes, LVD 46, LVD 47, LDA 48, LVD 49, LDA 50, LDA 52, LVD 53, LVD 54, LVD 55, LDA 56, Laboratoire central d'analyses de Metz, LDA 58, LDA 59, LDA 60, LDA 61, LDA 62, LDA 63, Laboratoire des Pyrénées, Centre d'analyses Méditerranée – Pyrénées, LVD 67, LVD 68, LVD 69, LVD 70, LVD 71, LVD 72, LDA 73, LVD 74, LVD 76, LVD 77, LDA 78, LVD 79, LVD 80, Laboratoire départemental d'hygiène d'Albi, LVD 82, LDA 83, LDA 84, LDA 85, Laboratoire d'analyse et de sécurité alimentaire de Poitiers, LVD 87, LVD 88, Institut départemental de l'environnement et d'analyses d'Auxerre, LDAV972 ;

The toxicology laboratory of the veterinary VetAgro Sup Campus of Lyon ;

The Biomathematics and epidemiology unit of the veterinary VetAgro Sup Campus of Lyon ;

The Vectorial transmission and epidemiosurveillance of parasitic diseases laboratory of the University of Reims Champagne‐Ardenne ;

The national reference laboratories of ANSES and the Pasteur Institute ;

Vet Diagnostics ;

The rabies and wildlife laboratory of ANSES in Nancy which centralizes the network’s data since 1993, participes to the network’s running and contributes to the scientific valorisation of results.

7

INTRODUCTION

SAGIR is a network for the epidemiological surveillance of wild birds and terrestrial mammals, in particular species whose hunting is authorized in France. This surveillance, based on a constant partnership between the Hunting federations and the National hunting and wildlife agency (ONCFS) has been carried out since 1955 (de Lavaur, 1978), it was consolidated in 1972 and has taken on its its present dimension in 1986 under the name SAGIR. It has four main objectives : i) characterization in time and space of wild bird and mammal diseases with priority stake ? for the health of populations , ii) early detection of the appearance of new wildlife diseases, iii) monitoring of acute non‐intentional effects of the use of phytopharmaceutical products in agriculture on wild birds and mammals, iv) knowledge of wildlife pathogens that are transmissible to humans, with a view to the latter’s protection, in particular that of hunters. This general long‐term monitoring also contributes to the knowledge of pathogens that are shared by wildlife and domestic animals. This data is fundamental for hunting managers and for risk managers and assessors.

To carry out this epidemiological surveillance, the SAGIR network uses the detection of wild bird and mammal mortality and the determination of its aetiology.

This report presents the results of the SAGIR network recorded from 2006 to 2008, representing 11 634 wild bird and mammal specimens. These animals were discovered dead or sick in the field, collected by the network observers and then analyzed by the departemental veterinary laboratories. The analysis systematically consists of an autopsy and, when necessary, further examinations are performed to specify and confirm the post mortem diagnosis. The data sources of this report are macroscopic findings, the results of the histology, bacteriology, virology, parasitology, toxicology and other veterinary areas of specialization.

After outlining the methods, we detail the results per species, per year and per “département”. The main diagnosed infectious and parasitic diseases are presented in a specific chapter and the following chapter presents intoxication cases. Although the results generated by the network can generally only be analysed in a descriptive way, they can extend scientific questioning through new analytical hypotheses. In this case, another research team takes over or works in partnership with the network. Indeed, for a sound understanding of a health phenomenon, general surveillance data are insufficient, and must be completed with further results steming from a strengthened and targeted surveillance, bringing together different specialists in ecology, veterinary diagnostic, pathology, epidemiology, to have an integrated vision of the phenomenon. Six examples are highlighted in this report to illustrate the complementarity between the SAGIR and other epidemiosurveillance systems.

8

I METHODS

I.A Epidemiological characteristics of the SAGIR network The SAGIR network is a generalist1 epidemiological surveillance2 network with a nationwide geographical coverage. The data’s mode of production is passive3 but can, on the occasion of a special operation, be active4. The network uses opportunistic or convenience sampling (Dohoo et al., 2003), in other words, the most accessible dead or sick animals. For all these reasons, the collected sample is not a representative sample of the population. It is a qualitative monitoring, it enables the detection of the presence of a species’ pathogen at a place and time t, but it does not for the time being allow the quantification of a health phenomenon and hence calculation of prevalence5. The SAGIR network is a participative network, which means that its smooth running relies predominantly on the contribution of field actors in the network, on their motivation and the information available to them on health episodes affecting wildlife. I.B Definition of the case A SAGIR case corresponds to an animal observed dead or sick, incapable of returning to the natural environment or a hunter‐killed animal showing signs of disease at the opening of the carcass. Healthy animals, showing no signs of disease and shot or trapped for the screening of a specific disease are not considered as a SAGIR case and are not exploited within the framework of this report. An exploitable SAGIR case is a SAGIR case with an autopsy report and a SAGIR form, whose information has been centralized in the SAGIR database. A non exploitable SAGIR case is thus a case for which :

- the SAGIR form is missing;

- the case history is vague6 or incomplete7 ;

- the autopsy has not been performed ;

- or the autopsy report has not been submitted for the data centralization.

Advanced state of decomposition of the dead bodies is not a criterion for exclusion of the exploitable SAGIR case since their autopsy has, in many cases, revealed the presence of a pathogen of relevance for the species’ conservation or human health.

For the present report, in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively 3,5 % , 2,6 % and 2,1 % of SAGIR cases could not be considered as exploitable.

Throughout this report, the term « case » is used for exploitable SAGIR cases. I.C Interpretation of results For the interpretation of the SAGIR network data, it is essential to bear in mind the constraints imposed by the sampling and the various filters applied to the different stages of the SAGIR protocol. They are not detailed in the present report and mainly come within the following :

1 Non specialized. The network is interested in several diseases and in several animal species. 2 This more general term is used to refer to all epidemiosurveillance et and epidemiovigilance networks. An epidemiosurveillance network is devoted to the surveillance of diseases that are present in a territory, as opposed to an epidemiovigilance network, which enables the detection of the appearance of a new or exotic disease (Dufour and Hendrikx, 2007). 3 One describes as passive any surveillance activity relying on the spontaneous notification of cases or suspected cases of the disease monitored by the actors as data sources. It is thus impossible to know in advance the number, nature and localization of the data collected by the network. This type of organization is adapted to situations where the purpose is to give an early warning in case of the appearance or re‐appearance of a disease (Dufour et Hendrikx, 2007). 4 The production is active when it is organized specifically, with for example a sampling design, sampling and analyses performed for the sole purpose of epidemiosurveillance (Toma et al., 2001). 5 Measurement of the frequency of a disease existing at a time t (P = total number of cases at a time t / total population at this time). 6 For example, with only the observed species, the municipality and the date of discovery mentioned. 7 For example, with only the specimen’s genus, without mention of the species.

9

- mortality detection probability. The dead bodies are not actively searched for, they are discovered in a fortuitous manner. The observed apparent mortality does not represent the true mortality and largely underestimates it;

- the reporting of spontaneous information based on the motivation of observers and SAGIR ITD ; - a non‐homogeneous sampling process from one departement to another. Indeed, the selection of individuals whose analysis results will be entered into the database is subjected to a series of non standardized filters, which are as many sources of selective forces (and hence of bias) coming into play in the building of the sample, from the reporting of the dead body to the collection, transport and analysis to the centralization.

For all these reasons, caution is required in the data exploitation, notably with regard to the quantification of a health phenomenon or the data representativeness for a wildlife species. The SAGIR network is adapted to the detection of the presence of a disease, so we shall restrict this report to the disease outbreaks8. On the other hand, it is difficult to conclude on the absence of a disease in the absence of data. The absence of data in a municipality does not necessarily imply that there is no wildlife mortality or disease in this municipality. It can result from the true absence of the pathogen or from a lack of observation (hostile environment, presence of important vegetation cover, absence of ITD in the departement, …), or lack of reporting or analysis (absence of LDAV in the departement, dead body in a too advanced state of decomposition, …). Similarly, SAGIR data allow the comparison in time and place of a pathogen’s presence with all the necessary caution. On the other hand, to compare the amplitude of a health phenomenon in time and space, a prior analysis of the increase in case numbers and an assessment of the portion due to a higher observation pressure and that attributable to the true progression of the disease are required, which is impossible with the general SAGIR protocol.

II SPATIO‐TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CASES FROM 2006 TO 2008

II.A Annual distribution of cases After a substantial increase in the number of cases in 2006, the collection in 2007 and 2008 decreased to its usual level, with a number of cases close to that recorded in 2005 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 : Number of cases recorded from 2005* to 2008 by the SAGIR network. * from Terrier et al., 2006

In relation with the international context of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1 HP) circulation, the monitoring of wild bird mortality and the screening of higly pathogenic viruses (H5 or H7) were strengthened from September 2005 onwards, relying on the SAGIR network in rural areas. The

8 Epidemiological unit of pathological cases, clinically expressed or not, occurring in the same place during a limited period of time (Toma et al., 2001).

Source : SAGIR data.. ONCFS/FNC/FDC netw

ork

Number of cases

2005 2006 2007 2008

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

n = 3475

n = 6271

n = 3043

n = 2320

10

general system aimed at collecting dead birds in a good state of preservation in a context of abnormal mortality, i.e., at least five birds found dead at the same site within a radius of 500 meters, within 7 days. Following the discovery of three dead common pochards Aythya ferina in the Dombes (Ain) and the detection of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1 HP) on 13 February 2006, the general system was strengthened, including any dead swan observed in France and any dead anatid observed in an at‐risk wetland area, notably in this region where the wild bird mortality surveillance pressure was very high. From February to August 2006, 734 dead birds were collected in the Ain, including 470 on the Dombes ponds, showing evidence of the avian influenza epizootic in this territory (Baroux et al., 2007 ; Hars et al., 2007a ; Hars et al., 2008). Apart from this mortality episode in the Ain, the increase in SAGIR cases in 2006 compared to 2005, related to the increase in the number of birds collected by the network (Figure 1), was not associated with a mortality caused by avian influenza. On the other hand, this increase was the consequence of the strengthening of the surveillance following the vigilance appeal in the avian influenza context. This increased surveillance led to an increase in the number of notifications by observers9 and in SAGIR cases. Meanwhile, the notifications by new observers among the public were taken into account in this particular context, thereby increasing the « avian influenza » effect on the SAGIR network. The intervention of these new observers likely explains the increasing proportion of non exploitable SAGIR cases in 2006 (cf. Chapter I.1.), which reminds one that the intervention of trained people guarantees the effectiveness of the territory surveillance. This episode in 2006 is a new illustration of SAGIR’s capacity to strengthen its surveillance to face a particular health event, thanks to the mobilization of the network’s observers under the coordination of departemental technical representatives 10 (ITD) and the national team. In 2007, 949 dead birds11 were collected and analysed in France within the framework of the monitoring of avian influenza virus circulation among wild birds, which is much less than in 200612. In 2008, slightly over 350 dead birds were subjected to a search for the highly pathogenic influenza virus. This significant decrease in the number of dead birds analysed in 2007 and 2008 is the expression of lower levels of awareness of the new observers outside of a health crisis period. It is above all indicative of a lack of clarity for the network of the role officially entrusted to it. II.B Monthly distribution of cases SAGIR cases are recorded continuously throughout the year (Figure 2). The substantial increase in cases recorded in February and March 2006 reflects the public reaction to the announcement of the first avian influenza case in the Ain in February 2006 (cf. Chapter II.1.). This effect becomes less marked in April and even less marked as from May 2006.

9 Observers of the SAGIR network are mainly hunters, technicians of hunting federations and agents of the ONCFS. 10 ITD are in charge of the running of the SAGIR network in their departement. There are two of them in each departement, one from the

departemental hunting federation and the other from the ONCFS departemental service. 11 For the record, only 7 anatid specimens, 5 mute swans Cygnus olor and 2 mallards Anas plathyrhynchos, were found to be infected in Moselle in

2007 and no test on specimens collected in 2008 was found positive. 12 One should note that not all of these cases appear in the 2007 and 2008 bars in Figure 1 since all the results of the avian influenza monitoring on

wild birds found dead or sick were not entered into the SAGIR database in 2007, as well as in 2008.

11

2006

2007

2008

Figure 2 : Monthly distribution of cases in 2006, 2007, 2008. Apart from anatids, among the species well represented in the SAGIR sample, the number of roe deer Capreolus capreolus collected in February and March 2006, as well as in November and December 2006, is higher than the number collected in the same months for the years 2007 and 2008 (Figure 3). A higher number of injuries was recorded in roe deer in February and March 2006, whereas digestive system diseases (enterotoxaemia, parasitism, diarrhoea) dominated in November and December 2006. In July, August and September 2007, the three peaks were notably due to an increase in cases of polyparasitized roe deer, as well as an increase in the number of injuries in July 2007. Since 1997, many departements have reported unusual levels of dead roe deer discoveries, associated or not with a population decrease. A large number of investigations were conducted within the framework of the SAGIR network, notably in search of a specific pathogen associated with this phenomenon called MAC for mortalité anormale du chevreuil, i.e., abnormal roe deer mortality. No specific pathogen has been identified. On the other hand, autopsy reports often reported a massive parasitic infestation, associated with a marked thinness. At the individual scale, these results did not provide satisfactory answers for managers. Nevertheless, their national aggregation enabled biologists to elaborate hypotheses on this mortality phenomenon. The roe deer’s high sensitivity to its environment contributes to explain the observed or perceived mortality (Delorme et al., 2008). Nevertheless, as far as possible, the surveillance of roe deer mortality causes is essential for the early detection of diseases. The MAC issue is a good illustration of the collaborative approach between different fields (ecology, population dynamics, pathology, epidemiology,

histology, parasitology, …), essential to the understanding of some mortality events that pathology alone cannot always explain.

Source : SA

GIR data.. ONCFS/FNC/FDC netw

ork

Number of cases

December

0

100

200

300

500

400

600

January Feb. March April May June July Aug. September Oct. November

n = 1429

n = 1743

12

2006

2007

2008

2006

2007

2008

Figure 3 : Monthly distribution of roe deer cases in 2006, 2007, 2008.

Figure 4 : Monthly distribution of European brown hare cases in 2006, 2007, 2008.

With more than 1000 cases per year, the European brown hare Lepus europaeus is the most represented species in the SAGIR sample. In 2006, 2007 and 2008, their numbers increased in autumn (Figure 4). This observation is an abiding feature in the SAGIR network, and is probably related to the higher surveillance pressure during the hunting period for this species and to some pathologies frequently observed during this season (see infra). On the other hand it is difficult to interpret the other monthly and interannual differences in the number of cases. It is worth noting however that cases of pasteurellosis, coccidiosis and European brown hare syndrom (EBHS) were observed rather in November 2006 and in September and October 2007. This is indicative of a later appearance of the disease in 2006 or of a time‐lag in observation. The large number of cases in Octobre 2007 is explained by the more frequent identification of tularemia as the aetiology of death. Lastly, the higher number of cases in March 2007 is explained by an upsurge in cases of pseudotuberculosis, coccidiosis, EBHS, and a not insignificant proportion of unspecified causes of death. II.C Distribution of cases per municipality The distribution of cases per municipality (Figure 5) illustrates the nationwide coverage of the network and the dynamism of observers and SAGIR ITD, as well as of the LDAV. No data is available in a few departements. In some departements, the absence of LDAV or of an animal health activity in the departemental laboratory is a handicap for the optimal running of the SAGIR network. The web site http://carmen.carmencarto.fr/index.php?map=espece_sagir.map&service_idx=38W presents the distribution per municipality and per year of species that are well represented in SAGIR, such as the mallard Anas plathyrhyncos, roe deer, European brown hare and European rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus.

Source : SAGIR data.. ONCFS/FNC/FDC netw

ork

Number of cases

0

Janv

50

100

150

250

200

0

50

100

150

250

200Fev

Mar

Apr

May

june

July

Aug

Sept

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Fev

March

Apr

May

June

July

Aug

Sept

oct

Nov

Dec

13

Figure 5 : Distribution of cases per municipality in metropolitan France and in Martinique in 2006, 2007 and 2008.

2006*

2007

2008

Number of cases /

Number of cases /

Number of cases / municipality

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

* H5N1 HP cases are not all represented .

.

..

.

.

14

III SAMPLE DESCRIPTION

III.A Species Since 1986, SAGIR cases concern 205 species of wild birds and mammals (Appendix 1). Seven species represent 80 % of SAGIR cases with, in decreasing order of their numbers :

1. European brown hare

2. Roe deer ;

3. European rabbit;

4. Wild boar Sus scrofa ;

5. Red fox Vulpes vulpes ;

6. Mallard ;

7. Wood pigeon Columba palumbus.

Although a few species are flagship species in the SAGIR network, the species richness of the SAGIR sample is exceptional and, to our knowledge, unique in France and in Europe (Figure 6). Whereas departemental hunting federations are heedful of the monitoring of mortality in all the species whose hunting is authorized in France, the SAGIR network is also interested in other species of wild birds and mammals in France, in particular with regard to raptor intoxications for example (see infra). The common buzzard Buteo buteo thus ranks in tenth position in the list of the most represented species in SAGIR since 1986.

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

16000

18000

20000

Lepus europaeus

Capreolus capreolus

Oryctolagus cuniculus

Sus scrofa

Vulpes vulpes

Anas platyrhuncos

Columba palumbus

Rupicapra rupicapra

Cygnus olor

Buteo buteo

Columba sp.

Perdix perdix

Cervus elaphus

Sturnus vulgaris

Streptopelia decaocto

Perdix sp.

Phasianus colchicus

Alectoris rufa

Meles m

eles

Capra ibex

Streptopelia sp.

Fulica

atra

Passer domesticus

Larus sp.

Felix lynx

Scolopax rusticola

Ardea

cinerea

Carduelis chloris

Martes foina

Turdus merula

Columba livia

Milvus milvus

Larus michahellis

Rupicapra pyrenaica

Larus ridibundus

Ovis gmelini musimon

Carduelis spinus

others

Number of cases

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

%

Figure 6 : Ranking of species in the SAGIR sample sinced 1986 according to the number of cases (Pareto diagram).

This wild bird species diversity increased in 2006 as a result of the avian influenza episode (Figure 7).

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

15

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Figure 7 : Species richness of the SAGIR sample in 2005*, 2006, 2007 and 2008. * from Terrier et al., 2006

Within the framework of a strengthened surveillance, the SAGIR network has shown its capacity to detect in the field the mortality of specimens belonging to species other than those usually monitored by the network, notably of small size, deemed to be more difficult to observe (Figure 8). This episode is an illustration of SAGIR’s capacity to rapidly adapt to health stakes of the moment with unequalled results.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

moineau domestique

merle noir

héron cendré

tarin des aulnes

buse variable

verdier d'Europe

étourneau sansonnet

tourterelle turque

Figure 8 : Monthly distribution of cases in 2006 for the common buzzard*, starling, grey heron, blackbird, house sparrow, siskin, collared dove and greenfinch. * For the scientific names of these species, refer to Appendix 1.

Looking at the seven first species mainly collected from 2005 to 2008 (Table I), the effect of the avian influenza episode on the species’ structure of the sample is clear : the classically observed structure of the database changes drastically in 2006 and in 2007, and the ranking is again respected in 2008.

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

2007 2008 20062005

Number of species

Jan. Fev. March April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec.

Number of cases

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

Passer domesticus

Turdus merula

Ardea cinerea

Carduelis spinus

Buteo buteo

Carduelis chloris

Sturnus vulgaris

Streptopelia decaocto

16

Table I : The 7 most represented species in the database in 2005*, 2006, 2007 and 2008. * from Terrier et al., 2006

Rank 2005 2006 2007 2008

1 Europe brown hare mallard European brown hare Europe brown hare

2 Roe deer European brown hare Roe deer Roe deer

3 Red fox Roe deer mallard Wild boar

4 European rabbit pigeon sp. European rabbit European rabbit

5 Mallard Mute swan Wild boar Red fox

6 Wild boar starling Red fox Wood pigeon

7 Wood pigeon Common buzzard Mute swan Mallard

III.B Dead animals vs. sick animals From 2006 to 2008, SAGIR cases relating to animals found alive and sick represent 20 % of the total number of cases. For 50 % of these cases, the observer and/or the LDAV have described symptoms in the SAGIR form. This information is invaluable for the orientation of the post mortem diagnosis and the determination of further possible associated examinations. It was not possible in this report to compare the number of animals found alive during this period with that found in previous years.

IV MAIN INFECTIOUS AND PARASITIC DISEASES DIAGNOSED BETWEEN 2006 AND 2008

IV.A New pathogens and diseases identified between 2006 and 2008 A new pathogen or a new disease refers to a pathogen or a disease revealed for the first time in SAGIR’s history since the data centralization, either because no case had been observed until then, or because the case concerned a new wild bird or mammal species. Between 2006 and 2008, 10 new diseases or pathogens have been observed by the network (Table II).

17

Table II : List of the new pathogens and diseases identified by SAGIR between 2006 and 2008.

DISEASE SPECIES* (number of specimens, departement, date, observation)

Botulism (D) Clostridium botulinum, type D toxin

Yellow‐legged gull1 (410, 66, May 2008)

Duck viral enteritis Mute swan (1, 68, August 2008, lesions (pathological?) diagnosis)

FCO Red deer (2, 51, December 2007, presence unrelated to death)

Avian histomoniasis Mute swan (1, 26, February 2006), coot (1, 39, February 2006)

H5N1 HP1 Common buzzard (1, 01, 2006), mute swan (54, 01, 2006), common pochard (6, 01, 2006), grey heron (1, 01, 2006), grey lag goose (1, 01, 2006)

Leptospirosis Eurasian beaver (2, 39, October and November 2008)

Mycoplasma agalactiae Alpine ibex (9, 73, 2007‐2008, isolated in the lungs)

Pseudotuberculosis Red squirrel (2, 33, February 2006), Eurasian beaver2 (1, 68, May 2006), coypu (1, 26, May 2007)

Salmonellosis Salmonella mbandaka

Stock dove (4, 35, January 2007)

Haemorrhagic syndrome Hawfinch (6/1, 11/39, 2006, unidentified aetiology)

Tetrameres infestation13 Wood pigeon (1, 36, January 2008) * For the scientific names of these species, refer to Appendix 1. 1 from Hars et al., 2006 2 Identified in European beaver in 1998 and in coypu in 2002 in Indre‐et‐Loire

Among these diseases, type D botulism had not been documented so far in wildlife in France, contrary to types C and E. Duck viral enteritis or duck plague is an acute, contagious disease, sometimes chronic, due to a herpesvirus affecting ducks, geese and swans. Even though outbreaks are uncommon, it is a permanent threat for poultry flocks and ornamental birds and for the avifauna. The status of wild anatids is difficult to know but wild ducks in the Anas genus seem less prone to the clinical expression than domestic palmipedes. They could play a role in the contamination of poultry farms14. IV.B Diseases with an impact on wildlife species’ populations observed between 2006 and 2008 IV.B.1 Species whose hunting is authorized, key events

IV.B.1.1 Wood pigeon

The year 2006 was marked by a significant Newcastle disease episode in Pas‐de‐Calais, as well as a higher number of fowl pox cases. During the 2007‐2008 winter, a high wood pigeon mortality was observed and reported in many departements (Aveyron, Charente, Charente‐Maritime, Côtes d’Armor, Dordogne, Finistère, Gard, Gers, Haute‐Loire, Ille et Vilaine, Isère, Loire‐Atlantique, Marne, Mayenne, Nièvre, Orne, Savoie, Vendée, Yonne and departements of the Centre and Ile de France regions). Every winter, pigeons are found dead as a result of lesions caused by the parasite, but the phenomenon occurred on a larger scale during the 2007‐2008 winter. For example, mortality was estimated at 1 000 individuals between December 2007 and February 2008 in Vendée and at 400 (wood pigeons and doves both taken into account) in Ille et Vilaine with a mortality peak in February. Further details on the distribution of cases are described in SAGIR letters n° 161 and n° 162 (http://www.oncfs.gouv.fr/Reseau‐SAGIR‐Surveillance‐Sanitaire‐de‐la‐Faune‐Sauvage‐ru105/Consulter‐les‐lettres‐SAGIR‐ar297). IV.B.1.2 Stock dove

The month of July 2008 was marked by a significant trichomonosis episode in chicks recorded in Mayenne.

13 Tetrameres infestation is a parasitic affection due to small nematodes localized in the proventriculitis and causing emaciation (wasting, loss of

weight) and regurgitation. 14 Fot further information, you can consult http://www.avicampus.fr/PDF/PDFpathologie/Herpesvirosecanard.pdf

18

IV.B.1.3 Collared dove

Trichomonosis also affected the collared dove Streptopelia decaocto during these three years of monitoring. Cases have been reported in Aude, Dordogne, Gers, Gironde, Indre, Loiret, Nièvre and Pas‐de‐Calais. Aspergillosis marked the year 2006, with the mortality of about a hundred individuals. IV.B.1.4 European rabbit

Myxomatosis, which is endemic in France, is not often reported within the framework of the SAGIR network, despite its impact on rabbit populations. Over 3 years, 29 cases have been notified in 17 departements. The clinical features of this viral disease vary according to the virus strain and virulence. There are several forms of the disease : the first is nodular, the other is called amyxomatous. For the nodular form, the clinical picture is easy to recognize and sick or dead rabbits are often not submitted to the LDAV for analysis ; cases are not or rarely notified. As regards the attenuated nodular form and the amyxomatous form, symptoms are not as characteristic and the auto‐examination made by the observer leads to an underestimation the disease. A confirmation diagnosis performed by the LDAV is required. Between 2006 and 2008, 62 viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD) cases were observed and reported in 30 departements. Between 2006 and 2008, 52 hepatic and digestive coccidiosis, associated with diarrhoea, inflammation and intestine congestion, were observed and reported in young individuals. Lastly, in 15 % of cases, the aetiology of death could not be de determined. In 2006 in particular, the LDAV reported in the majority of cases an absence of lesions at the autopsy on analysed rabbits. IV.B.1.5 Roe deer

Cases of listeriosis, encephalitis, massive Oestrus ovis infestations and polyparasitism were recorded each year. Reported pasteurellosis cases were more numerous in 2006. The LDAV observed quite frequently tumors of the digestive and respiratory systems, concerning adults as well as young animals. IV.B.1.6 Chamois

Cases of abscess disease were observed in the chamois Rupicapra rupicapra in 2006 in Drôme and Isère, and in 2008 in Drôme and Savoie. A higher number of pasteurellosis cases was observed in 2006, as well as other respiratory diseases. IV.B.1.7 Red fox

Many cases of mange were reported in the red fox, confirming that this disease is mortal in this species. IV.B.1.8 European brown hare IV.B.1.8.1 Dominant pathological features

EBHS (European brown hare syndrom) or viral hepatitis of hares was the dominant pathology in 2006 and 2007, overtaken in 200815 by tularemia (Figure 9). For all the reasons evoked in Chapter I. Methods, the percentages mentioned here are not representative of the diseases’ prevalence in hare populations. On the other hand, they allow the identification of a trend in the occurrence of diseases in hare populations or of the interest shown in them.

15 This trend for EBHS in 2008 has to be confirmed by further data analyses.

19

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2005 2006 2007 2008

t raumat isme

t ularémie

EBHS

pseudot uberculose

inf ect ion respirat oire

past eurellose

coccidiose

sept icémie

colibacillose

Figure 9 : Dominant pathological features in the European brown hare – Relative evolution between 2005 and 2008*. The % were calculated by dividing the number of individuals screened positive for a disease by the number of hares collected in the year. * 2008 results have to be further analysed to confirm these trends. Injuries represent a major and constant cause of European brown hare mortality. In some cases, they can be facilitated by exposure to chemical substances that modify behaviour (cf. Chapter V). Pasteurellosis occupies an important place among brown hare diseases recorded by the SAGIR network. The spatial distribution of outbreaks is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 : Cumulated presence and distribution per departement of pasteurellosis in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008. Further details on pseudotuberculosis and tularemia are presented in the chapter on zoonoses (see infra). Information on EBHS is detailed below. Reproductive disorders (abortion, dystocia, genital infection) have been described for 18 cases in 2006, 11 in 2007 and 5 in 2008, without the aetiological agent being identified.

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

% of hares affected

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

1 year

2 years

3 years

4 years

20

Cases of verminous pneumonia were observed in brown hares killed by hunters in 2008. At the time of evisceration, many brown‐beige colored nodules, localized in the lungs, were observed by hunters and analysed at the LDAV. These observations are recurrent, particularly in some territories of the Tarn. The histological examination of lesions revealed the presence of nematode parasites in the bronchi and alveoli and led to the diagnosis of suppurative bronchopneumonia of verminous origin. Field observations mention animals in good condition, with no abnormal behaviour and showing no sign of impairment. At the date of edition of the present report, new information on this parasitic pathology has led to the definition of a specific study programme in several departements16. IV.B.1.8.2 Zoom on European brown hare syndrome (EBHS)

EBHS is a disease of relevance for managers and makes it worth developing the knowledge obtained by the SAGIR network. The data on macroscopic findings observed by the LDAV have been analysed in the present report. The approach used is an example of what can be carried out for the brown hare and other species and for other pathologies. Nevetheless, it was not possible in this report to develop all these analyses. We chose to develop the example of EBHS. IV.B.1.8.2.1 EBHS macroscopic findings

The analysis of macroscopic data presents a double interest : i) monitoring of the macroscopic expression of the disease as a tool for the detection of an evolution of the virus pathogenicity , ii) inventory of evocative lesions to optimize the triggering of the analysis. In a first stage, lesions were considered independently from organs to rank them according to observation frequency for EBHS cases (Figure 11). The operation enabled the isolation of lesions of low occurrence. The same approach was used with the organs (Figure 12).

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

HEM

ORRHAG

ECO

NGESTION

HYPERTROPH

YINFLAM

MATION

NO LESIONS

ABNORM

AL CO

LOR

NECRO

SIS

ROASTING PICTURE

TRANSUDATE/EXSUDATE

PURU

LENT SECRETION

PETECH

IAE

DEGEN

ERATION

OTH

ERS

Frequency

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

%

Figure 11 : Frequency of lesions associated with EBHS in the European brown hare between 2006 and 2008 (Pareto diagram). The category « other» includes lesions whose observation frequency is below 1 %.

16 For further information, consult the SAGIR letters n° 165 and n° 167 (http://www.oncfs.gouv.fr/Reseau‐SAGIR‐Surveillance‐Sanitaire‐de‐la‐Faune‐Sauvage‐ru105/Consulter‐les‐lettres‐SAGIR‐ar297).

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

21

0

20

40

60

80

100

trachea

liver

lung

spleen

intestine

others organs

nose

kidney

thorax

abdomen

bronchus

stom

ach

sinus

others

Frequency

0

20

40

60

80

100

%

Figure 12 : Frequency of affected organs in EBHS cases in the European brown hare between 2006 and 2008 (Pareto diagram). The category « other» includes organs whose observation frequency is below 1 %.

In a second stage, the principal associations between the modalities « lesion » and « organ » were determined by a factorial correspondence analysis (Figure 13).

ASPECT CUIT

COLORATION ANORMALECONGESTION DEGENERESCENCE

HEMORRAGIE

HYPERTROPHIE

INFLAMMATION

NECROSE

PETECHIES

SECRETION MUCOPURULENTE

TRANSUDAT/ EXSUDAT

abdomen

bouche

broncheestomac

foie

intest in

nez

poumon

rate

rein

sinus

thorax

trachee

-1

0

1

2

3

4

-2 -1 0 1 2

- - axe F 1 ( 3 7.9 5 %) - - >

Figure 13 : Representation of the principal lesion/organ associations in EBHS cases in the European brown hare from 2006 to 2008.

Based on this analysis, the modalities having the most significant contributions in EBHS cases are the following lesion/organ associations :

- hypertrophy/spleen ; - transudate‐exsudate/abdomen ;

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

F2 axis (23,77 %)

F1 axis (37,95 %)

22

- abnormal coloration/liver ; - haemorrhage/trachea.

In other words, these associations have likely been determining to set the diagnoses. The second factorial plane retained (not represented here) showed an opposition of the association hypertrophy/spleen and necrosis‐ cooked aspect ‐ abnormal coloration/liver. This means that the spleen hypertrophy is rarely observed when the liver has a cooked aspect, an abnormal coloration or necrotic lesions. Lastly, the macroscopic findings most frequently described were revealed by a statistical classification represented in the dendrogram in Figure 14.

Figure 14 : Classification of lesion associations most frequently described in EBHS cases in the European brown hare between 2006 and 2008. The lesion/organ modalities most frequently associated in EBHS cases are haemorrhage/trachea and hypertrophy/spleen. The pair congestion/lung is aggregated to this group. The main symptoms recorded for EBHS cases were haemorrhages, mostly nasal, diarrhoea, depilation and foam at the nostrils. The other described symptoms were behaviour problems, staggers, apathy, myoclonia and jaundice. However, this information was not systematically present in SAGIR forms, it was thus not possible to analyse these symptoms using the same approach as previously. These analyses establish that no evolution of the macroscopic or symptomatological findings of EBHS in the European brown hare was detected from 2006 to 2008. IV.B.1.8.2.2 Distribution of cases per departement from 2005 to 2008

The cumulated years of EBHS presence from 2005 to 2008 enables one to identify the departements where the virus seems to be endemic (Figure 15). The departements of the south of France are particularly concerned. However, the notification of outbreaks from one year to another is not systematic. It depends on the probability of detecting the outbreak (lethal episode or not, presence of observers in the field, …) and the probability that this oubreak, once detected, is reported to the network by the observer (disease recurrence, knowledge of the disease, interest in the disease, brown hare’s demographic situation in the departement, …). Thus, the absence of EBHS case in a departement or the apparent disappearance of the disease in a departement does not necessarily mean that it is not or no longer present. All the data should thus be interpreted with caution.

Dissimilarity

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

23

Figure 15 : Cumulated presence and distripution per departement of EBHS in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008. Spread of the EBHS virus in brown hare populations – Retrospective analysis. by Jean‐Sébastien GUITTON, ONCFS, Direction of studies and research

During the last quarter of the year 2004, the SAGIR network observed a higher number of EBHS cases than in previous years in several departements of the south‐east of France. The spatio‐temporal description of this epizootic enabled the ONCFS to put forward and test several hypotheses concerning various epidemiological aspects of this still little‐known disease. The hypothesis that the increase in the number of cases in 2004 could be related to the emergence of a new virus genotype was first tested. The sequencing performed by the AFSSA supported this hypothesis and showed a replacement of ancient viral genotypes by the novel ones over the 10 previous years. A modelling work was then initiated to investigate whether it is necessary to assume that new genotypes have a selective

advantage (in the form of only partial cross‐immunity with the ancient genotypes) to explain the observed dynamics. The first results do not favour this hypothesis : the low exposure of brown hare populations to EBHS in 2003 could have played a more determining role. Some groups of municipalities appeared to have been little or not affected by the disease in 2004. A serological study carried out in 2005 aimed, but unsuccessfully, at showing that the EBHS virus might have little circulated in these populations, for example due to a relative spatial isolation. Lastly, the spatial spread of the epizootics of 2004 described using the SAGIR network data at the scale of several departements was irregular. A work under way aims at showing that this variation is related to a landscape structure (rivers, forests, relief) which influences contacts between brown hares and hence the spread of the virus. These works are in progress or nearing publication.

IV.B.2 Protected species, key events

IV.B.2.1 Alpine ibex

During the 2007‐2008 winter, about ten dead Alpine ibex were transported to the departemental veterinary laboratory of Savoie (LDAV73). This number seemed large compared to previous years, particularly as they were adults, and led to the assumption that the mortality was likely to be abnormal (see SAGIR Letter17 n° 161). Meanwhile, the Vanoise National Park reported an unusually high mortality in some populations cores, in particular in the Champagny en Vanoise and Villarodin le Bourget territories. The

17 SAGIR Letters available at http://www.oncfs.gouv.fr/Reseau‐SAGIR‐Surveillance‐Sanitaire‐de‐la‐Faune‐Sauvage‐ru105/Consulter‐les‐lettres‐

SAGIR‐ar297.

1 year

2 years

3 years

4 years

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

24

performed analyses enabled the identification of the two main diseases found in the species, i.e., keratoconjonctivitis and pneumonia. No new cause of death was thus identified. Within the framework of the detailed analyses performed by the LDAV73, along with the ANSES laboratory in Lyon, the bacteriology revealed for the first time the presence of the Mycoplasma agalactiae bacteria in the lungs of some ibex suffering from pneumonia. This observation raises questions concerning the bacteria’s role in the development of pneumonia in Alpine ibex and its potential impact on population dynamics. A pluridisciplinary collaborative study is currently underway to contribute to answering these questions.

IV.B.2.2 Brent goose

Aspergillosis cases were observed in the brent goose Branta bernicla in the Manche in 2006. IV.B.2.3 Red squirrel

The causes of death of red squirrel specimens collected by the SAGIR network have an infectious origin, with the observation of pseudotuberculosis and respiratory infection, the aetiological agent of which was unidentified. IV.B.2.4 Gulls

In early March 2008, the Norman Ornithological Group reported to the SAGIR network a grouped gull mortality on Tatihou Island in the Manche (see SAGIR Letter11 n° 161). Slightly over 60 individuals, mostly herring gulls Larus argentatus, but also lesser black‐backed gulls Larus fuscus and great black‐backed gulls Larus marinus, were found dead or dying on this small territory. In a first stage, 19 post‐mortem examinations were performed by the Manche departemental veterinary laboratory. Based on the macroscopic findings and the sudden occurrence of the phenomenon, the first hypotheses turned towards toxicology, in particular an intoxication by anticoagulants. The toxicology laboratory of the veterinary VetAgro Sup Campus of Lyon analysed all the submitted samples and searched for most of the molecules on the market. The analyses did not enable the detection of the anticoagulants searched for and thus invalidated our initial hypothesis. Meanwhile, gulls were still found dead or dying, only on the island territory, the number of victims reaching about a hundred. In order to target the further investigations, 2 dying gulls and 3 new dead ones were analysed again and tissue samples were submitted to the histology laboratory Vet Diagnostics (www.vetdiagnostics.fr). Any infectious hypothesis was hence discarded and another toxic hypothesis was put forward in relation with the observed behaviour of the sick animals. Chloralose was identified on one sample. In May 2008, 300 yellow‐legged gulls were found dead or dying on La Corrège island in the middle of the Salses‐Leucate pond in Pyrénées‐Orientales. The analyses performed within the framework of the network confirmed type D botulism. The opportunistic and necrophagous feeding behaviour of this species contributed to maintain the phenomenon. State services, in particular the prefecture, veterinary services and health affairs, could use this information to reassure the populations, although the initial terms used in their communication (« risk for humans », « transmissible germ », « precaution principle », …) had at first needlessly alerted them. For this reason, the basic language used during botulism episodes needs to be precise (see SAGIR Letter11 n° 162). IV.B.2.5 Black‐headed gull

Salmonella typhimurium was identified in several cases of black‐headed gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus mortality in 2006 in the Somme and in 2008 in Indre‐et‐Loire. Visceral gout was diagnosed in 21 gulls in Pas‐de‐Calais (see SAGIR Letter11 n° 158). IV.B.2.6 Siskin

Salmonella typhimurium and group B Salmonella were identified in several siskin Carduelis spinus specimens found dead in 2006 and 2008 in several departements (Alpes de Haute‐Provence, Creuse, Drôme, Isère, Loire, Savoie, Tarn).

25

IV.B.2.7 Greenfinch

Salmonella typhimurium and group B Salmonella were identified in several greenfinch Carduelis chloris specimens found dead in 2006 and 2008 in several departements (Cantal, Corrèze, Côte d’Armor, Creuse, Drôme, Gers, Jura, Tarn). A mortality episode due to trichomonosis was recorded in greenfinch during the 2007‐2008 winter. IV.C Zoonotic pathogens identified between 2006 and 2008 IV.C.1 Tularemia

Compared to the 2005 situation, the number of departements where a least one tularemia case in the European brown hare was detected by SAGIR was higher in 2008 (Figure 16). However, given the SAGIR protocol, it is impossible to specify whether it was due to a true progression of the disease, an increase in the observation pressure, an improvement in the disease detection techniques or a more systematic search for the disease even on animals that did not show any evocative sign.

Figure 16 : Cumulated presence and distribution per departement of tularemia in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008. The 2007‐2008 winter was marked by an important increase, during a limited period of time, of tularemia cases in the European brown hare and in humans. The increase in human cases was not accompanied by an increase of contact with the brown hare, suggesting one or several common sources of contamination for these 2 species (Mailles et al., 2010). IV.C.2 Swine erysipelas

Swine erysipelas was detected in the wild boar in April 2007 in the Loire, in the roe deer in June 2007 in the Alpes de Haute‐Provence and the Jura and in the European brown hare in November 2008 in Ardèche. IV.C.3 Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis was diagnosed in the Eurasian beaver in autumn 2008 in the Jura. IV.C.4 Pseudotuberculosis

Compared to the 2005 situation, the number of departements where at least one case of pseudotuberculosis in the European brown hare was detected by SAGIR was lower in 2008 (Figure 17).

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

1 year

2 years

3 years

4 years

26

However, one should bear in mind that the same caution as described above for tularemia is required in the interpretation.

Figure 17 : Cumulated presence and distribution per departement of pseudotuberculosis in the European brown hare from 2005 to 2008. IV.D Pathogens shared with domestic animals identified between 2006 and 2008 The SAGIR network analyses identified several pathogens or diseases shared with domestic animals. Between 2006 and 2008, waterfowl botulism, trichomonosis, Mycobacterium avium tuberculosis, fowl cholera and pox, Newcastle disease, classical swine fever in wild boar, bluetongue in the red deer, Brucella suis biovar 2 brucellosis in the European brown hare and the wild boar, salmonellosis and pasteurellosis in various wild bird and mammal species, babesiasis in the Pyrenean chamois, listeriosis in the roe deer , were identified.

V INTOXICATIONS IDENTIFIED BY SAGIR FROM 2006 TO 2008

V.A Identified causative agents of intoxications Between 2006 and 2008, the number of cases for which the cause of death was an intoxication reached 359 individuals. These intoxications were due to one or several molecules, listed in Table III. In this table, an individual is mentioned as many times as toxic agents have been identified in its tissues, which explains the total number 411. Intoxications concerned a similar proportion of birds as mammals. Birds were predominantly intoxicated by chloralose, cholinesterase inhibitors and imidaclopride. Mammals were mostly intoxicated by anticoagulants and cholinesterase inhibitors.

Source : Données SA

GIR. R

éseau

ONCFS/FNC/FDC

1 year

2 years

3 years

4 years

27

Table III : Toxicants quantified per species* and per year from 2006 to 2008. * for species’ scientific names, refer to Appendix 1.

Name of the agent Name of the species 2006 2007 2008 Total

ALDICARBE Red deer 1 1 Rook 1 1 Beech marten 1 1 Europe brown hare 1 1 Wild boar 2 2

ALDRINE Peregrine falcon 4 4 Red fox 1 1

Common buzzard 2 2 Roe deer 2 2 Storck sp. 2 2 Rook 4 4 European rabbit 2 2 European brown hare 11 1 12 Red fox 3 3 6

ANTICOAGULANTS (unidentified molecules)

Wild boar 3 4 7

BROMADIOLONE Common buzzard 2 2 Roe deer 1 2 3 Barn owl 1 1 Comon kestrel 1 1 European rabbit 2 2 European brown hare 4 5 9 Red kite 1 1 Red‐legged partridge 1 1 Red fox 3 9 5 17 Wild boar 4 12 16 32 Collared dove 1 1

CARBOFURAN Common buzzard 7 3 10 Roe deer 1 1 2 Raccoon‐dog 1 1 Mallard 1 1 Starling 2 2 Beech marten 1 1 European hedgehog 2 2 European rabbit 1 1 Red kite 1 1 Black‐headed gull 1 1 Roose sp. 1 1 Red‐legged partridge 1 1 Red fox 5 3 1 9 European robin 1 1 Wild boar 2 2

CHLORALOSE Golden eagle 1 1 Common buzzard 1 1 2 Duck sp. 1 1 Roe deer 2 2 Mallard 7 9 9 25 Crow sp. 1 1 Mute swan 1 1 Pheasant sp. 1 1 2 Coot 1 1 Gull sp. 4 4 Eurasian eagle‐owl 1 1 Grey heron 1 1 Red kite 1 1 House sparrow 3 2 5 Black‐headed gull 1 1 Grey partridge 1 2 1 4 Common wood pigeon 1 2 1 4 Pigeon sp. 4 4 9 17

28

coypu 1 1 Red fox 1 1 Wild boar 3 6 9 Turtle dove 1 1 Collared dove 7 2 9

CHLORMEPHOS Common wood pigeon 1 1

CHLOROPHACINONE Red deer 1 1 Roe deer 2 1 3 Common crane 2 2 Grey heron 1 1 European rabbit 2 2 European brown hare 5 7 2 14 Rock pigeon 2 2 Wild boar 1 1 2

SODIUM CHLORIDE Chamois 1 1

COPPER Mute swan 1 1 Griffon vulture 1 1 2

DICHLORODIPHENYLDICHLOROETHANE Wild boar 1 1

DICHLORVOS European brown hare 1 1 Wild boar 4 4

DIFENACOUM European rabbit 1 1 Red fox 1 1 Wild boar 2 1 3

FIPRONIL Pheasant sp. 1 1

FLOCOUMAFENE Eurasian beaver 1 1

FLUORENE Wild boar 1 1

HEPTACHLOR Common buzzard 1 1 Peregrine falcon 1 1 Grey partridge 1 1 Red fox 1 1

IMIDACLOPRIDE Grey partridge 4 4 Partridge sp. 6 6 Stock dove 4 4 Pigeon sp. 1 4 2 7