Rise of Romanticism 2015

-

Upload

andrei-tris -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Rise of Romanticism 2015

-

History of English Literature

~The Eighteenth Century~

English Romanticism

-

The Rise of the Pre-Romantic Sensibility

The Romantic sensibility: born out of the paradoxes and contradictions of the Enlightenment

The Cult of Reason the attitude of humanitarianism and social benevolence (initiated by the Deists) the cult of Feeling, the Age of Sensibility / the Sentimental revolution

Virtue: associated no longer with Reason, but with Feeling Increasing attention to emotional response (e.g. the sentimental

novel); new interest in the workings of the creative mind (abundance of biographies) favoured by:

the growing interest in the individual psychology the preoccupation of 18th century philosophy with the

processes of thought (John Locke, An Essay concerning Human Understanding, 1690)

-

In poetry: a shift from the Neoclassic emphasis on the public relevance of art as a product of civilisation to the interest in subjective experience

the rise of a kind of meditative poetry which assumed a personal voice and became the vehicle of private feeling from the confident optimism of the Age of Reason to a

preference for the expression of melancholy and dark thoughts the macabre

e.g. The Graveyard School of poetry: Thomas Parnell: A Night-piece on Death (1722) Robert Blair: The Grave (1743) Thomas Gray: Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751) James MacPherson: A Night Piece (mid-late 18th c.)

In fiction: from the light of Reason and attention to the observable world of fact to the darker aspects of the human self and to the supernatural from the realistic to the Gothic novel

e.g. Horace Walpole: The Castle of Otranto (1764) Matthew Lewis's The Monk (1796)

-

Thomas Gray: Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751)

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day*, The lowing* herd wind* slowly oer the lea*, The plowman homeward plods* his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me. [] Beneath those rugged* elms*, that yew trees*

shade, Where heaves the turf* in many a mouldering*

heap, Each in his narrow cell forever laid, The rude* forefathers* of the hamlet sleep. [] Full many a gem* of purest ray serene, The dark unfathomed* caves of ocean bear: Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, And waste its sweetness on the desert air. [] Far from the madding* crowds ignoble* strife, Their sober* wishes never learnt to stray*; Along the cool sequestered* vale of life They kept the noiseless tenor* of their way.

the curfew tolls the knell of parting day dangtul clopotului de sear anun sfritul zilei to low a mugi to wind, wound a erpui, a merge erpuit lea camp, pajite, lunc to plod to walk slowly, with difficulty and great effort rugged solid, masiv; cu nfiare aspr, sever,

nenduplecat elm ulm yew tree tis turf brazd de iarb (the turf heaves: se nal

movile acoperite de iarb) to moulder to decay slowly (a putrezi, a se

descompune) rude simplu, modest (uneducated, unlearned,

simple) forefather strbun, strmo hamlet ctun full many a gem very many gems (precious

stones, jewels) unfathomed whose depth has not been taken,

which has not been fathomed (measured for depth)

madding maddening ignoble mrav, nemernic sober cumptat, moderat to stray to wander away from its proper place (a se

abate, a se rtci) sequestered quiet and hidden away from people tenor curs, trecere, direcie

-

Shift from the Augustan focus on contemporary civilisation and its enlightened cosmopolitanism to a new sense of and INTEREST IN THE PAST

The revival of local and national mythologies, the interest in folk legend, art and poetry; interest in early poetic forms PRIMITIVISM: admiration for and revival of early forms;

Primitivism: cultural reaction against Neoclassicism, as well as against the sophistication, luxury and materialism of urban civilisation Thomas Percy: Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (collection of popular

ballads, 1765) James Macpherson, The Poems of Ossian (1765) interest in Britains Celtic

past (Ossian: Irish bard and hero, 3rd c. A.D. Macpherson claimed that he had translated his poems from Erse/Gaelic the Highlands of Scotland) themes: heroic virtue, nostalgia, regret; descriptions of wild, sublime nature Thomas Chatterton interest in the Middle Ages (claimed to offer transcripts

of poems of mediaeval monk Thomas Rowley 15th c.) The works of both MacPherson and Chatterton turned out to be literary

forgeries

Primitivism

-

Henry Wallis, Death of Cahtterton, 1856 I thought of Chatterton, the marvellous Boy,

The sleepless Soul that perished in his pride. William Wordsworth, Resolution and Independence, 1807

-

Town vs. countryside

Primitivism: nostalgia for a supposed Golden Age the praise of the state of nature the influence of Jean Jacques Rousseau

The Enlightenment critical spirit: now oriented towards civilisation (the highest achievement of the Age of Reason) abundance of optimistic utopias the idealisation of country life

The sentimental opposition between TOWN and COUNTRY almost an Augustan convention (e.g. Henry Fielding, Oliver Goldsmith)

Poetry: Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village (1770) an idyllic picture of a

rural paradise laments the disintegration of the traditional way of country life under the pressure of the new economic tendencies

George Crabbe, The Village (1783) the realistic picture of countryside he claims to describe village life as Truth will paint it and as bard will not (a reaction against the unreality and artificiality of the pastoral convention)

-

William Cowper, The Task (1785)

God made the country, and man made the town. What wonder then that health and virtue, gifts That can alone make sweet the bitter draught That life holds to all, should most abound And least be threatened in the fields and groves?

-

From Oliver Goldsmith, The Deserted Village

Sweet Auburn! loveliest village of the plain, Where health and plenty cheered the labouring

swain*, Where smiling spring its earliest visit paid, And parting summers* lingering* blooms delayed: Dear lovely bowers* of innocence and ease*, Seat of my youth, when every sport* could please, How often have I loitered* oer thy green*, Where humble happiness endeared each

scene*; How often have I paused on* every charm, The sheltered cot*, the cultivated farm, The never-failing brook*, the busy* mill, The decent church that topped* the neighbouring

hill.

labouring swain steanul / omul truditor

parting summer the summer which is departing

lingering ncet, zbavnic bower sla ease tihn, linite, pace sport zburdlnicie to loiter a hoinri oer over green pajite endeared each scene made

each secene more loveable to pause on a zbovi asupra cot csu never-failing brook prul care nu seac niciodat busy full of work or activity topped stood on top of

-

From George Crabbe, The Village

Ye* gentle* souls who dream of rural ease, Whom the smooth* stream and smoother sonnet

please, Go! if the peaceful cot your praises share, Go, look within, and ask if peace be there. If peace be his that drooping* weary* sire, Or theirs, that offspring* round their feeble* fire; Or hers, the matron* pale, whose trembling hand Turns on the wretched* hearth* the expiring*

brand*! [] yonder* see that hoary swain*, whose age Can with no cares except his own engage; Who, propped* on that rude* staff*, looks up to see The bare arms* broken from the withering* tree On which, a boy, he climbed the loftiest bough*, Then his first joy, but his sad emblem now.

ye you (pl.) gentle nobil, ales, generos smooth calm, linitit drooping aplecat, ncovoiat weary exhausted (istovit) sire (poetic) tat, printe offspring vlstar, urma feeble plpnd, slab matron mam de familie wretched biet, jalnic, nenorocit hearth vatr, cmin expiring dying (care se stinge) brand tciune yonder (poetic) there hoary swain steanul crunt /nins/

venerabil propped proptit, sprijinit, rezemat rude rudimentary, coarse; simple,

lacking adornments staff toiag bare arms ramurile/crengile

desfrunzite withering decaying, losing vitality (care se usuc) loftiest bough ramura cea mai nalt

-

New attitude to Nature

The Augustan treatment of nature the local / topographical poem e.g. Alexander Pope, Windsor Forest (1713) mythological allusions; celebration of natural variety, harmoniously confused integration Man-Nature through work a mirror to social harmony

The poetry of sensibility: different treatment of the theme of Nature

The praise of solitude; the emphasis on the spiritual comforts offered by nature, its healing effect, its superior joys The use of the natural detail in the creation of mood and

atmosphere Unprecedented attention to detail; precision of notation

-

Alexander Pope, Windsor Forest

Thy* forests, Windsor! and thy green retreats*, At once the Monarchs and the Muses seats*, Invite my lays*. Be present, sylvan maids*! Unlock your springs and open all your shades. [] Here hills and vales, the woodland and the plain Here earth and water, seem to strive again; Not chaos-like together crushed and bruised, But as the world, harmoniously confused: Where order in variety we see, And where, though all things differ, all agree. [] Here Ceres gifts in waving prospect* stand, And nodding tempt the joyful reapers* hand. Rich Industry sits smiling on the plains, And peace and plenty tell, a Stuart reigns.

thy your retreat refugiu,

adpost seat lca lay cntec, balad sylvan maids

nymphs of the wood

Ceres goddess of cereals and of the harvest in Roman mythology

Ceres gifts in waving prospect the corn in the fields is waving in the wind

reaper secertor

-

James Thomson The Seasons (1726-30) from Autumn Thus, solitary, and in pensive guise*, Oft* let me wander oer the russet mead* And through the saddened grove, where scarce is heard One dying strain*, to cheer* the woodmans toil* He comes! he comes! in every breeze the Power Of Philosophic Melancholy comes! [] As fast the correspondent passions rise, As varied, and as high: Devotion, raised To rapture* and divine astonishment; The love of Nature unconfined*, and, chief*, Of human race; the large ambitious wish To make them blessed; the sigh for suffering worth* Lost in obscurity; the noble scorn* Of tyrant-pride; the fearless great resolves *() The sympathies of love and friendship dear, With all the social offspring of the heart..

pensive guise looking thoughtful; in a meditative mood

oft often russet mead pajitea ruginie strain melodie to cheer to shout in praise or

support toil hard continuous work

(trud) rapture ecstasy; ecstatic joy unconfined unlimited chief (chiefly) most important suffering worth men of merit

and virtue who suffer scorn contempt, disdain (dispre) resolve resolution (hotrre,

decizie) tyrant pride the arrogance of

arbitrary or unjust power the social offspring of the

heart the community, whom the heart feels as a family

-

Features of English Romanticism English Romanticism: between 1798 (W. Wordsworth and S.T.

Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads; 1800: Wordsworths Preface to its second edition: the first manifesto) and 1832 (The Reform Act / The Representation of the People Act)

Inspired by the American and French Revolutions increasing radicalism of political thought and championship of progressive social causes

The sense of hope, of an apocalyptic change influence of religious Nonconformism on English radicalism politics through the perspective of Biblical prophecy (renovate old earth, the regeneration of the human race)

Versions of Romantic rebellion: openly supportive of a social, political or ideological cause (e.g.

Shelley) manifested as withdrawal into a world rendered ideal by the

Imagination (the sensitive individual rejecting the common world; the misfit, the genius, etc.)

-

Romantic rewriting of myth William Blake, The Four Zoas (17971804) Percy Bysshe Shelley, Prometheus Unbound (1820) George Gordon Byron, Cain (1821)

John Keats, Hyperion, The Fall of Hyperion (181819)

Romantic myths of the Rebel and the Victim: Satan/Lucifer, Prometheus, Cain

Main themes: freedom, spiritual and political emancipation

Myth: in the service of utopian social-political thought

-

The assertion of the individual Self the value of individual experience

The influence of J.J. Rousseau the description of the solitary inner self in his Confessions, published in 1782

The lyrical exploration of the inner self: the autobiographical poem: Wordsworth The

Prelude (1815/1850); the crisis poem: Coleridge Dejection. An Ode

(written 1802), Shelley Ode to the West Wind (written 1819)

The dramatic projection of the Romantic self e.g. Byrons dramatic poems the Byronic hero (e.g. Manfred, 1817)

-

The cult of the extinct the preoccupation with the past, with origins, with

reminiscing Romantic primitivism The theme of childhood Wordsworth, Blake Interest in the Middle Ages, in folk poetry and legend

Coleridge The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1798; Christabel, 1797; 1800; Keats La Belle Dame Sans Merci, 1819;

Lamia, 1820

-

Joseph Mallord Willliam TURNER, Caernarvon Castle, 1799 (13th century)

-

John Constable (1776 - 1837) Hadley Castle, 1829 (13th century)

-

J. M. W. Turner, Modern Rome, Campo Vacino, 1839

-

John Constable, Stonehenge, 1835

-

Romantic nature: Either wild, overwhelming, irregular, sublime, or

simple, delicately beautiful Pervasive theme in English Romanticism: the

exploration of the relation between NATURE and CONSCIOUSNESS

The rediscovery of the superiority of Nature to Art / Civilisation;

The valuation of the spontaneous, the unpremeditated, of freedom from the bondage of convention (both in the expressions of human nature and in poetry)

-

John Constable Stour Valley and Deadham church, 1814

-

John Constable Deadham Lock and Mill, 1820

-

JMW Turner Snow-Storm. Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth, 1842

-

JMW Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway, 1844

-

Hostility towards Augustan aesthetics Programmatic cultivation of simple, unsophisticated forms; the

increasing preference of blank verse over the heroic couplet (William Blake: the great cage of the Augustan couplet) the great models: Shakespeare and Milton

The rejection of the notions of poetic diction and decorum; the rejection of tradition in favour of innovation (but: the second generation of Romantics returned to Augustan genres like the satire, the ode, the hymn)

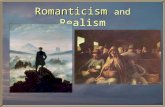

Augustan art: mimetic (i.e concerned with faithful representation/imitation of reality) and pragmatic (i.e. concerned with obtaining certain effects on the audience)

Romantic art: expressive shift of focus from audience to the creator: emphasis on the poets natural genius, on emotional spontaneity and creative imagination

-

M.H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp. Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition (1953)

Art is essentially the internal made external, resulting from a creative process operating under the impulse of feeling, and embodying the combined product of the poets perceptions, thoughts and feelings. The primary source and subject matter of a poem, therefore, are the attributes and actions of the poets own mind; or if aspects of the external world, then these only as they are converted from fact to poetry by the feelings and operations of the poets mind

-

The belief in Imagination as the supreme faculty of the human mind

Imagination affords access to realities and truths to which the ordinary intelligence is blind

It can modify reality the Apocalypse by Imagination M.H. Abrams, Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in

Romantic Literature (1971): Faith in an apocalypse by revelation had been replaced by faith in an

apocalypse by revolution, and this now gave way to faith in an apocalypse by imagination or cognition. In the () frame of Romantic thought, the mind of man confronts the old heaven and earth and possesses within itself the power () to transform them into a new heaven and a new earth, by means of a total revolution of consciousness

The close relationship NatureImagination (e.g. Wordsworth, Coleridge)

-

William Wordsworth: (Imagination) in truth Is but another name for absolute power And clearest insight, amplitude of mind And reason, in its most exalted mood. (The Prelude)

William Blake: To see the world in a grain of sand, And Heaven in a wild flower; To hold Infivity in the palm of your hand, And Eternity in an hour. (Auguries of Innocence)

P.B. Shelley: Imagination: the mind acting upon () thoughts so as to color them

with its own light, and composing from them, as from elements, other thoughts, each containing within itself the principle of its own integrity"; the great instrument of moral good

The Poet: a seer, gifted with a peculiar insight into the nature of reality. And this reality is a timeless, unchanging, complete order, of which the familiar world is but a broken reflection.

(A Defence of Poetry, 1821)

-

William Blake:

I assert for myself that I do not behold the outward creation and that to me it is hindrance and not action; it is as the dirt upon my feet, no part of me. What, it will be questioned, when the sun rises, do you not see a round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea? O no, no, I see an innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying Holy, holy, holy is the Lord Almighty. I question not my corporeal or vegetative eye any more than I would question a window concerning a sight: I look through it and not with it.

I know that this world is a world of imagination and vision. I see everything I paint in this world, but everybody does not see alike. To the eye of a miser, a Guinea is more beautiful than the sun, and a bag worn with the use of money has more beautiful proportions than a vine filled with grapes. To me this world is all one continued vision of fancy or Imagination. What is it sets Homer, Virgil and Milton in so high a rank of art? Why is the Bible more entertaining and instructive than any other book? Is it not because they are addressed to the Imagination, which is Spiritual Sensation, and but mediately to the Understanding or Reason?