Rise of emerging economies changes the world trade map — HSBC Global Connections

-

Upload

mrittunjay -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of Rise of emerging economies changes the world trade map — HSBC Global Connections

Brought to you by

28 May 2012

Catherine Bolgar

Rise of emerging economies changes

the world trade map

Buyers are looking for complex and structured solutions inthe supply chain that provide connectivity globally betweenthemselves and their suppliers.

he evolution of supply chains is forging new trade corridors around the world,

T

“Opportunities for new business or growth of existing

business may exist in markets that weren't very evident

before the crisis

creating new opportunities in emerging market economies.

"It's not just about trade between for example China and the U.S. or

China and Europe. There are new strands of activity that are growing

fast," says Adrian Rigby, Global Deputy Head of Trade and Receivables Finance

for HSBC in London. "In more difficult economic times, businesses are re-

engineering themselves and hunting out new markets."

Many of the new opportunities arise in fast-growing emerging market

economies, especially those with expanding import and export markets. The

trade aspect is important because it indicates a certain level of

interconnectedness with global supply chains, as well as a certain threshold of

infrastructure and regulatory development to make it possible to do business.

"You can't have network trade without industrialization," says Richard Kozul-

Wright, Head of the Unit on Economic Cooperation and Integration among

Developing Countries at the United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development (Unctad), in Geneva. Network trade accounts for more than 75% of

total developing country trade, with China responsible for about 60% of that.

Trade by low- and medium-income countries has increased to about 20% of

world trade today from about 8% in the early 1990s. The trend of developing

economies of the world trading between themselves, often called south-south

trade, has picked up speed since the 2008 global economic crisis, says

Przemyslaw Kowalski, Economist at the Organization for Economic Cooperation

and Development in Paris. Some developed countries still haven't recovered fully

from the crisis, while others—mostly emerging market economies—didn't dip as

much and have fully recovered in trade.

That means that since the economic crisis, opportunities for new business or

growth of existing business may exist in markets that weren't very evident

before the crisis, Mr. Rigby of HSBC says. "Corridor creators" are what HSBC calls

businesses that seek out the best trade partners to drive competitive advantage,

regardless of location.

The crisis just accelerated changes that had already started in global supply

chains.

Supply chains consist of four things: a supply source, a destination, an

intermediate point and a final product, says ManMohan Sodhi, Professor of

Operations and Supply Chain Management at the Cass Business School of the

City University London. "Any combination of those is a supply chain," he says.

"All of them are changing now."

Destinations are changing—countries that were supply sources have also

started buying products, Dr. Sodhi says. Some are actually buying locally goods

that also are produced for export, such as clothing made in India, and sold in

India and Europe by an international retailer. Warehouses have sprung up to

cater to the new supply chains.

Many sectors are seeing a shift from export-driven production to a mix of

domestic consumption and exports, says Mr. Kozul-Wright of Unctad. "It will be

interesting to see whether these value chains become more self-contained in

the developing world rather than depending on technology and markets in the

north," he says. "If the developing world would like to maintain the kind of

growth its had in the last decade, then value chains will have to have more local

content than in the past."

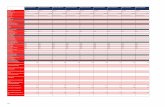

The top emerging growth importers between 2012 and 2016 are predicted to

be Egypt, with a 10% compound annual growth rate; Panama at 8.8%; Indonesia

at 8.5%; Brazil at 8%; Peru at 7.7%; Russia at 7.4%; Argentina and India, both at

6.8%; China at 6.6% and Saudi Arabia at 6.3%, according to "HSBC Global

Connections Trade Forecast Update," which HSBC published in February.

Sources are changing—companies that made their supply chains too lean got

burned by disruptions and are switching to a combination of long and short

supply chains to reduce risk, Dr. Sodhi explains. They continue to source

supplies from low-cost countries around the globe but they may also arrange

for nearshoring, with a secondary supplier much closer. "They still have the old

supply chain but now they have another one in addition to it," he says.

Stephan Wagner, Professor of Logistics Management at the Swiss Federal

Institute of Technology Zurich, known as ETH, also sees a move away from

single sourcing, despite its cost advantages, toward diverse sourcing to reduce

vulnerabilities. "Companies put suppliers in different regions to reduce risks

such as exchange-rate risk or geographic risk."

Another aspect of the sources also is changing: costs. Labor costs in coastal

China have risen, prompting some companies to chase lower cost labor farther

inland, or in other countries such as Vietnam, Cambodia or Sri Lanka, whose

costs haven't risen as much. "There’s a new source and a new trade corridor,"

Dr. Sodhi says.

The top emerging exporters to 2016, according to the HSBC report, are Egypt,

with 9.26% growth; Panama at 9.5%; Paraguay at 8.8%; India at 7.5%; Australia at

7%; Colombia at 6.7%; China at 6.6%; Peru at 6.4%; Indonesia at 6.1% and Poland

at 5.9%.

The intermediary point is changing—the Iceland volcano that disrupted air

traffic in 2010 made companies look at locations for transshipments of goods.

And these intermodal hubs aren't necessarily manufacturing anything. "They

say, bring it to my place and I'll route it further," Dr. Sodhi says. Some of these

transshipment hubs include Dubai, Singapore, Rotterdam, Panama and Egypt.

"In the future," says Dr. Wagner of ETH, "we will have more intraregional trade

and less trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific trade." Southeast Asia, in particular, is

poised for fast intraregional growth.

"As a consequence, logistics firms need to build up strong capacity for regional

trade," he adds. "You have to be able to run a logistics operation in China and

not just ship parts from Asia to Europe and finished products from Europe to

Asia."

The products are changing—most of the sectors forecast to have the fastest

growth over the next five years are those that support world trade, HSBC says.

Containers, packaging and plastics are expected to register 9% compound

annual growth between now and 2016. Binding products for foundries, which

are needed for infrastructure projects like roads and railways, are forecast to

rise 8.8%. Electrical energy, defined as all non-fossil fuel energy, is expected to

be the fastest-growing sector, at 9.1%.

The largest traded sectors now are oil and gas, petrochemicals and plastics,

cars, electronics, pharmaceuticals and iron and steel. HSBC forecasts continued

growth in all these, though it will be outstripped by the standout sectors

mentioned above.

On a consumer goods level, products also are changing. The growing middle

class in countries like China, India, Thailand and other countries is driving sales

of luxury goods. Now these countries, long the world's low-cost suppliers, are

becoming the buyers for goods whose supply source might be Italy or France,

Dr. Sodhi says.

Sometimes the change presents surprising challenges for companies. Some

European machinery companies have found that customers in emerging market

economies are willing to settle for quality that's just good enough, if it means a

lower price. "This can be problematic for companies that have a culture of high

technology and high precision," Dr. Wagner of ETH says. "The customers don't

need such high standards and aren’t willing to pay for it."

At the same time, companies in low-cost countries are increasingly engaging in

research, development and engineering to develop their own products, rather

than simply to manufacture what's been designed in traditional markets, he

notes.

"Local or national companies are moving beyond their initial stages of just

copying products. They are also investing in engineering in developed markets,"

Dr. Wagner says. He sees cases of Chinese machinery companies buying

medium-size German engineering companies, for example. "It's the next step of

the maturity curve," he says.

Foreign direct investment by OECD countries has contracted since 2008, notes

Mr. Kowalski of the OECD. But China and India "are heavily investing. Their role

in foreign investment has grown dramatically."

That leads to a fifth element—finance—which has evolved in the supply chain,

says Dr. Sodhi of Cass Business School. "Money is what makes global trade

possible," he says. Global banks are now acting on behalf of buyers and paying

suppliers directly.

Companies are looking for ways to manage risk in global supply chains,

particularly as they enter new markets, says Mr. Rigby of HSBC. Solutions

including trade credit insurance, guarantee structures and collection support

are growing strongly.

"Buyers are looking for complex and structured solutions in the supply chain

that provide connectivity globally between themselves and their suppliers," he

says. "We at HSBC are well-placed to meet that need."

Large buyers are increasingly seeking supply chain solutions, he says. These

take a number of forms, depending on where trading partners seek to allocate

and retain payment risk. Therefore flexibility of product solution is key.

The risk also has diversified with the supply chain, bringing in more

counterparties. "Finance really creates a new diversification point that we didn’t

talk about before," Dr. Sodhi says.

Catherine Bolgar is an independent writer covering business and

economics.