Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

-

Upload

emmanuel-amoki -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

1/60

Published by Winrock InternationalPolicy Analysis in Agriculture and Related Resource

Management

A Review of the

Biogas

Programme in

Nepal

Bishnu Bahadur Silwal

RESEARCH REPORT

SERIES NO. 42

NOVEMBER 1999

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

2/60

A REVIEW OF THE BIOGAS PROGRAMME

IN NEPAL

BISHNU BAHADUR SILWAL

Winrock International

Policy Analysis in Agriculture and Related Resource Management

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

3/60

Bishnu Bahadur Silwal is a freelance agricultural and rural development consultant.

Views expressed herein are the personal opinions of the author and do not necessarily

reflect those of HMGN, Ministry of Agriculture/Winrock International, or either of the

donor agencies supporting the Program (viz USAID and the Ford Foundation).

Winrock International acknowledges the generous help received from Mr Felix EW ter

Heegde, Programme Manager, BSP/SNV-Nepal in preparing this report.

Price: Rs 100

Winrock International

Policy Analysis in Agriculture and Related Resource Management

PO Box 1312, Kathmandu, Nepal

Telephones: 255109/255110/254687

Fax: 977-1-262904

E-mail: [email protected]

Anil Shrestha, Language Editor

Printed in Nepal at Mass Printing Press. November 1999.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

4/60

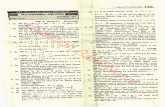

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Tables v

List of Maps V

List of Figures v

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms vi

I. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT AND CURRENT STATUS

OF BIOGAS IN NEPAL 1-2

Historical Development 1

Current Status of Biogas Programme in Nepal 2

II . ROLE OF TA-SUPPORTED BIOGAS SUPPORTPROGRAMME IN DEVELOPMENT OF BIOGAS IN NEPAL 2-11

Advent of External Support for Biogas Programme 2

Biogas Support Programme 7Advent of Biogas Support Programme 8

BSP: Project Design 8

Current Status of the BSP: Evaluation Findings 10

III. ROLE OF PRIVATE SECTOR IN BIOGAS

DEVELOPMENT IN NEPAL 12-17

Entry of Private Sector Construction Companies 12

IV. BIOGAS QUALITY CONTROL:

CURRENT PRACTICES AND ITS SUSTAINABILITY 17-21

Current Practices 17Aspects of Quality Control 17

Quality and Uniformity of Design 17

Quality of Construction 17

Quality of Operation and Maintenance by the Users 18

Present Practices of Quality Control 18

Agreement of Standard 18

Agreement on Penalty 18

Process of Quality Control 1:9

Sustainability 20

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

5/60

V. SUBSIDY, ITS ROLE IN PROMOTION OF BIOGAS PLANTS,

PLAN FOR PHASING AND POSSIBLE EFFECTS 21-25

History of Subsidy to Biogas Plants 21

Economic Rationale for the Subsidy 22

Impact of the Subsidy on Installation of Plants 23

Plan for Subsidy Phase-out 24

Possible Effects of the Phase out of the Subsidy 25

VI. FINANCING OF BIOGAS 25-27VII. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 28-32

Biogas Companies 28

Weaknesses and Problems of Companies . 29

Association of Biogas Companies 30

VUI. IMPACT OF BIOGAS PLANTS 32-35

IX. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 35-40

Summary 35

Recommendations 39

Annex Number of Biogas Plants Installed up to 31 August 1999 41-42

Annex List of Recognized Biogas Companies in Nepal

BIBLIOGRAPHY 43-44

Winrock International Policy Analysis in Agriculture and Related Resource Management List

of Publications 45-49

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

6/60

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Trend in the Share of the Private Sector 9

Table 2: Classification of the Companies and their Corresponding Shares in the

Total Plant Construction in FY1997/98 10

Table 3: Market Shares of the Companies Participating in the BSP 11

Table 4: Biogas Plants Installed under Various Subsidy Schemes by Year t9Table 5: Subsidy Rates for 1999/2000 (2056/57) 20

Table 6: A Typical Costs Structure Trend for 10 M Biogas Plant

(1991/92-1996/97) 22

Table 7: Finance and Financing Sources for the Biogas Plants Constructed under BSP

22

Table 8: Percentage of Solely-Equities Financed and Equities and Loan

Financed Plants 23

Table 9: Trend in the Entry of Companies 24

LIST OF MAP

Map: Biogas Plants Installed in Nepal by Districts 3

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Annual Biogas Plant Installation 4

Figure 2: Cumulative Biogas Plant Installation 5

Figure3: Number of Biogas Companies in Nepal 6

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

7/60

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ADB Asian Development Bank

ADBN Agricultural Development Bank, Nepal

AEPC Alternative Energy Promotion Centre

AEPDF Alternative Energy Promotion and Development ForumBSP Biogas Support Programme

cu.m. Cubic Metre

DGIS Directorate General for International Co-operation

DM Deutsche Mark

EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return

FIRR Financial Internal Rate of Return

FY Fiscal Year

GGC Gobar Gas Company

ha hectare

HMGN His Majesty's Government of Nepal

KfW Kreditanstalt fuer Wiederuafbau (German Financial Cooperation)It litre

MT Metric Ton

MTR Mid-term Review

NBE Nepal Bank Limited

NBPG Nepal Biogas Promotion Group

NGL Netherlands Guilder

NGO Non-government Organization

O&M Operation and Maintenance

R&D Research and Development

RBB Rastriya Banijya Bank

Rs Rupees

SFDP Small Farmer Development Programme

SNV Netherlands Development Organization

TA Technical Assistance

TCN Timber Corporation of Nepal

UMN United Mission to Nepal

UNCDF United Nations Capital Development Fund

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

USA1D United States Agency for International Development

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

8/60

1

A Review of the Biogas Programme in Nepal

I. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT AND

CURRENT STATUS OF BIOGAS IN NEPAL

Historical Development

The first biogas plant in Nepal is believed to have been installed in Godavari School in

the year 1955- After that, a few plants were installed on an experimental basis in various

parts of the country. Following the energy crisis of 1973, biogas drew some attention of

the authorities concerned and in the fiscal year (FY) 1975/76a year designated as the

Agriculture Year, some 290 plants were installed with interest-free loans from the

Agricultural Development Bank of Nepal (ADBN). Encouraged by the results, the

authorities established the Gobar Gas Company (GGC) as a subsidiary of the ADBN and

the Fuel Corporation of Nepal in 1977, with a mandate to promote biogas technology in

the country. Subsequently, a need for offering incentives to the plant owners was

realized. This led to the provision of a subsidy of Rs5,500 per plant in FY1982/83 as part

of a special rice programme in four Tarai districts.

Planned efforts were introduced from the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1985-1990), which

had a target of 4,000 plants, and provisioned 25per cent subsidy on investment costs and

50 per cent subsidy on bank loans. The programme, however, was not regularized, and,

as a result, the subsidy was provided only during the last two years of the plan period.

The GGC was somehow able to construct 3,862 plants during the plan period. With the

restoration of democracy in 1990, biogas was able to draw greater attention of the

authorities, who .by that time had recognized the importance of the sector and werecommitted to initiating measures to accelerate the pace of plant installation. As the first

step in this direction, the provision of a consistent subsidy was considered to be an

appropriate tool. So, in 1991, His Majesty's Government of Nepal (HMGN) announced a

subsidy scheme, which has been in effect until now. The rate of subsidy, initially, was

Rs7,000 for the Tarai and Rsl0,000 for the hills. Since 1995/96, a subsidy of Rsl2,000

has been added to the hill districts whose headquarters are not connected with road.

From FY1999/2000 onwards, the subsidy rates have been reduced by Rs 1,000: to

Rs6,000 in the Tarai, Rs9,000 in the hills and Rs. l 1,000 in the remote hills. However,

the 15 m3 and 20 m3 plants are not eligible for the subsidies.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

9/60

2

To farther promote plants of smaller sizes, an additional subsidy of Rsl,000 has been

offered for 4 m3 and 6m3 plants.

Current Status of Biogas Programme in Nepal

As to the current status ofthe biogas programme in Nepal, the following aspects arenoteworthy:

About 60,321 plants have been installed in 64 districts of the country (see map,figures 1 and 2, and Annex I).

A total of 50 companies are engaged in the installation of the biogas plants (seefigure 3 and Annex II).

The Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC), responsible for promotion andextension of all alternative energy, including the biogas, has been established.

The Biogas Support Programme (BSP), created as a part of external assistance, hasprotected the interests of the plant owners through the implementation of quality

control.

II. ROLE OF TA-SUPPORTED BIOGAS SUPPORT PROGRAMME

IN DEVELOPMENT OF BIOGAS IN NEPAL

Advent of External Support for Biogas Programme

With the increasing realization of importance of biogas as an alternative source of

energy, external sources of assistance were explored, initially for the provision of

subsidy. In this process, the first external assistance was obtained from the United

Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for the community biogas plants under the

Small Farmer Development Programme (SFDP) of the ADBN (Silwal, et al 1995).

Later, some community plants were also funded through the United Nations Children's

Fund (UNICEF), United States Aid for international Development (USAID) and United

Mission to Nepal (UMN). The first external assistance for household level biogas plants

was received from the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), which

provided 25 per cent subsidy on the investment costs of 6 m3 and 10 m3 plants. Similarly,

an Asian Development Bank (ADB)-funded forestry project also incorporated a

component to provision subsidy for about 5,000 plants.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

10/60

3

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

11/60

4

.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

12/60

5

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

13/60

6

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

14/60

7

All these assistance offered subsidy to the biogas plant owners on their capital

investments as well as on interests on loans taken from the ADBN. These instances of

assistance, however, were characterized by irregularity and lack of concrete policies.

Biogas Support Programme

Established in 1992 as a part of the BSP project supported by the Netherlandsgovernment, the BSP is a project staffed and operated by two expatriate experts and 18-

19 trained Nepalese personnel, and is responsible for the overall implementation of the

biogas programme in Nepal.

Advent ofBiogas Support Programme

Notwithstanding the establishment of the GGC in FY1976/77 for the development of

biogas and its modest achievement in terms of number of plants installed, the progress

was considered to be far below the potential. Therefore, some concrete actions were felt

necessary. In this context, the ADBN, through HMGN, approached the Netherlands

Development Organization (SNV) for some technical assistance and, in response, the

latter made available the services of two development associates to the GGC. After

working a little over one year, the development associates in 1990 offered their

conclusions and recommendations, among which, the following highlight the present

status of the biogas sub-sector in Nepal (Van nes 1997):

Major cost reduction through research & development (R&D) was not furtherpossible without compromising on the quality of plants; and

Reduction in private costs was possible only through provision of subsidies.Although subsidies on investment costs and on interest on bank loans had been in effect

since FY1975/76, their efficacy remained questionable due to their irregularity as well asinconsistency of policy. By the end of FY1990/91, the number of biogas plants installed

in the country totalled 6,615, most of which were owned by richer farmers located in the

Tarai. Another interesting study concluded by the development associates was on the

biogas potential in Nepal (Van nes 1992). Considering the cattle and buffalo populations

and their distribution, the study estimated the technical potentiality of about 1.5 million

biogas plants in the country. This means, in the beginning of the 1990s, only 0.4 per cent

of the potentiality was exploited. Similarly, a number of studies carried out by both

individual researchers and institutions indicated a need for framing plans and

implementing projects to exploit this vast potential. As a result, the development

associates in co-operation with HMGN, ADBN and GGC, prepared a proposal, namely

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

15/60

8

Biogas Support Programme (BSP), and submitted it in May 1991 to the Directorate

General for International Co-operation (DGIS) of the Government of Netherlands for

financial support. Thereafter, in November 1992, an agreement was concluded between

the Ministry of Finance on behalf of the HMGN and the SNV-Nepal on behalf of the

DGIS. This is considered to be a milestone in the history of biogas in Nepal.

BSP: Project DesignThe first BSP had, among others, the following long-term objectives:

Reduce environmental deterioration by substituting fuelwood and dung cakeby biogas.

Improve the health and sanitation conditions of the population by substituting thesmoke stoves by smokeless biogas stoves as well as by reducing the time spent in

collecting fuelwood.

Increase agricultural production by increasing the nutrients contents of the slurryobtained from the digester.

The total cost of the BSP was estimated at Rs492 million, of which Rs202 million was

granted by the Government of Netherlands and the rest was borne by the farmers either

in the form of equities or by borrowing loans from the bank. The first grant from the

Netherlands government was uti lized for providing technical assistance as well as

subsidies to the plant owners. The project was designed in such a way that it accelerated

the pace of biogas installation through the involvement of the existing GGC and the

ADBN in the installation of plants and in making loans to the borrowers respectively and

at the same time it allowed the participation of the various private companies willing to

construct the, plants as per the standards and norms of the project. Similarly, series of

negotiations, seminars and workshops were held with the commercial banks, specially

the Nepal Bank and the Rastriya Banijya Bank, for providing credit access to the

potent ial biogas plant owners. In order to achieve these object ives, the project was

divided into two phases. BSP I, implemented from November 1992 to July 1994, had the

following specific objectives:

Construction of 7,000 plants. Make biogas more attractive to the smaller farmers and farmers in the hills. Conduct necessary 3tudic3 to induce the participation of the private sector In the

construction of biogas plants.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

16/60

9

The first two objectives were met through provision of a flat rate of subsidy of Rs7,000

for the Tarai and Rsl0,000 for the hills. Higher subsidy in the hills was meant for

covering the higher transportation costs incurred in the transportation of construction

materials and appliances. The objective of participation of private sector was met by

instituting studies through consulting firms, which provided in-depth analyses of the

existing scenarios and offered recommendations (Karki, et al 1993a and 1993b). Based

on those studies, series of workshops, seminars and meetings were conducted, and

necessary arrangements were made for the participation of the private constructioncompanies. In the meantime, a mid-term evaluation carried out in May 1994 (HMGN &

SNV-Nepal 1994) offered the following recommendations:

Instead of a single GGC, the BSP should try to develop the biogas sub-sector as awhole.

More banks should be inducted in loan access. Research and standardization of biogas should be apart of the project. Training of masons and staffs of the companies and banks should be emphasized. In order to make the best use of the slurry obtained from the biogas digester,

extension work should be initiated and implemented immediately.

Monitoring and evaluation of the programmes should form an important part of the

project,

BSP II had the following objectives:

Construction of 13,200 plants. Make biogas more attractive to the smaller farmers and farmers in the hills. Support the establishment of an apex body to co-ordinate the different actors in the

biogas sector.

Encouraged by the results of Phase I and Phase II of the BSP, Phase III was designed in

1995 and proposals submitted to the governments of Netherlands and Germany. Unlike

in the past, where all the technical assistance and the subsidies were borne by the

Government of Netherlands, Phase III has been designed to involve the Government of

Germany as well. The overall objectives of Phase III of the BSP are as follows

(HMGN/SNV 1995):

Develop a commercially viable, market-oriented biogas industry. Increase the number of biogas plants by installing 100,000 additional plants during

the project period.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

17/60

10

Ensure the continued operation of the installed plants. Help in the production of quality gas valve, tap and lamp. Help in the establishment and strengthening of institutions related to the biogas sub-

sector for rendering sustainability to the biogas programme in the country.

An agreement was signed between the HMGN, Kreditanstalt fuer Wiederaufbau (KfW)

of German government and SNV-Nepal on 17 May 1997. The agreement laid downarrangements for the funding of the programme until July 1999. Further extension to

meet the set target is contingent upon the findings of the recently concluded evaluation

study (de Castro, et al 1999). According to the above-mentioned agreement, the funding

arrangements are as follows:

HMGN will contribute 10 per cent of the financing of investment subsidies in thefirst year of the programme (FY1996/97) and increase it by 2 percentage points

annually to reach 20 per cent in the last year of the project, ie FY2001/02.

For Part I (first three years) of BSP III, KfW will contribute up to DM14 million, ofwhich DM7.1 million will be used for providing subsidies to the plant owners and

DM6.9 million will be made available to ADBN for onlending to the borrowers for

installing plants.

SNV-Nepal will contribute up to NGL11.23 million, of which NGL8.83 million willbe used for technical assistance and the rest for providing the subsidies.

Current Status of the BSP: Evaluation Findings

A recently concluded mid-term review of Part I of BSP III has come up with the

following findings (de Castro, et al 1999):

Numerical Objective

There has been some lag in the installation of plants during Part 1 of Phase III of theBSP. As against the target of 35,500 plants by mid-July 1999, the production over that

period has been only 29,304 plants83% of the target with a lag of 6,169 plants. The

study attributed the low demand for biogas plants to the economic recession that has

been creeping for the past few years.

Size of the Biogas Plants

Invariably, all the past studies have pointed out the need to reduce the average size of the

biogas plants. Phase III has duly incorporated measures to address this objectivethe

flat rate of subsidy being one of the most effective ones in this regard. In turn, the

average size of the biogas plants is found to be decreasing. In 1990, the average size

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

18/60

11

was found to be 12.86 m3, which declined to 9.6 m3 in 1993. This, obviously, was the

result of the flat rate of subsidy, which encouraged plants of smaller sizes, as the net

cost to the owners decreases with the decline in the size. From 1995, another strategy

adopted by the BSP to encourage plants of smaller sizes was the introduction of bonus

to the companies that constructed plants of smaller sizes. This resulted in further reduction

of the average size to 8.2 m3 in 1997. During 1998/99, the average plant size has come down to

7.39 m3

.

Technical Quality of the Plants

Quality of plants constructed under the BSP has been receiving due consideration for the overall

sustainability of the biogas programme in Nepal. Quality of biogas plants implies a package of

benefits perceived by its user in terms of the total costs incurred in its installation. The

determinants of technical quality include: (a) quality of design, (b) quality of construction, (c)

quality of operation and maintenance of the plant by the users, and (d) quality of after-sales

services rendered by the construction company. The evaluation study, based on various annual

surveys, has concluded that the design of the plan was satisfactory to 88 per cent of the users.

Similarly, 92 per cent expressed their satisfaction over the location of the plant. Regarding

the materials used in the construction of the plants, 96 per cent of the users viewed that they

were up to the standard. After-sales services provided by the construction companies were

satisfactory to 95 per cent of the users. In sum, the present quality standard fixed by the BSP is

believed to be up to the standard.

The evaluation has also pointed out that the overall success of the biogas programme has been

possible because of:

Provision and continuity of subsidy for the plant owners. Creation of a conducive policy environment for the entry of significant number of private

construction companies. .

Protection of the interests of the plant owners through the provision of quality controlof the plants constructed by the companies, including the GGC. and

Building of the institutional capability of the various actors involved in the biogasprogramme in Nepal.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

19/60

12

III. ROLE OF PRIVATE SECTOR IN BIOGASDEVELOPMENT IN NEPAL

Entry of Private Sector Construction Companies

Although the GGC played a pivotal role in the dissemination of biogas technology in the country,

its capacity to meet the demand was considered inadequate since not long after its establishment in

1977. Being a subsidiary of the ADBN, the only source for channelling the subsidies provided

under various programmes, the GGC, however, enjoyed a monopoly status and displayed inherent

weaknesses in its operation, especially in terms of work-force, cost of plants and flexibility in

pricing. The pace of progress that the GGC was recording necessitated some thoughts on the entry

of private companies to provide competitive atmosphere and hence explore the vast potentiality

that existed in the sub-sector. Recognizing this fact, some private companies were approaching the

ADBN for getting permission to construct plants and avail of the subsidies. What was lacking was

a mechanism to establish standards and norms to be applied to the private companies and monitortheir work in terms of design, construction, pricing, after-sales services, and repair and

maintenance. Experiences from other sectors and sub-sectors were enough to warn the illusive

nature of private sector entry in activities that lacked well-defined standards and norms. Very

often, the motive was to reap benefits from certain packages and then switch over to some other

business.

In spite of these weaknesses of the private companies, the ADBN had started issuing permission to

a couple of companies to install plants from FY1989/90 on an experimental basis. Their work,

however, was found to be flawed in a number of ways and the Bank even detected cases of fraud.

With the implementation of the BSP, however, the subsidy was effectively controlled by the BSPand it did not issue permission until the privatization studies were carried out as per the agreement

between the HMGN and SNV-Nepal (BSP 1991). An independent consulting firm carried out the

studies (Karki, et al 1993a and 1993b) and it was closely steered by a committee composed of

representatives from the ministries, departments, banks and relevant agencies.

Following the recommendations made by the studies, private companies were invited to

participate in the BSP since the beginning of BSP II. Of the various rules and regulations laid

down by the studies and confirmed by the mid-term evaluation carried out in May 1994

(HMGN/SNV-Nepal 1994), the following are the major aspects that the companies,

including the GGC, are to follow:

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

20/60

13

Establish a standard design to be adopted by all companies, including the GGC1. Ensure the provision of trained masons for the construction. Guarantee quality appliances. Provide guarantee on structure and appliances. Submit plant completion report and annual maintenance report to the BSP. Visit the plants annually. Comply with the quota of construction based on office network and availability

of trained work-force.

The entry of the private companies, which number 50 at present, has had a positive

impact on the progress of the biogas plants. As can be seen, from a mere annual

average of approximately 400 plants constructed by the GGC since its inception to

1992/93, the numbers since the entry of private companies have averaged at

approximately 6,000. This is, indeed, a remarkable achievement of the BSP

programme. With the entry of the private construction companies, there has been a

steady decline in the share of the GGC, a para-statal organization. The market shares

of the private companies and the GGC over time are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Trend in the Share of The Private Sector

YearCate-

goryUp to

91/92

92/93 93/94 94/95 95/96 96/97 97/98 98/99 Total

In Number

GGC 8 824 3 321 3 508 2 952 3 267 2 369 2415 2 203 28 859

Private 96 846 2 145 2 165 3 894 6018 7 454 8 844 31 462

Total 8 920 4 167 5 653 5 117 7 161 8 387 9 869 11 047 60 321

In Percentage

GGC 99 80 62 58 46 28 24 20 48

Private 1 20 38 42 54 72 76 80 52

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

Sources: Van nes 1997, SNV-BSP and.

As can be seen from Table 1, the private sector has gradually built up its share in

the total plants. With a mere share of 1 per cent until 1991/92, it has been able to

increase its share to 80 per cent by the end of 1998/99. Numerically, this is a welcome

1

All the companies at present are to follow the model, namely GGC2047.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

21/60

14

measure. In order to explore the vast potentiality that exists in the biogas sub-sector, the

participation of the private sector is extremely important. Of the total 60321 plants

installed up to the end of1998/99, the private sector's share is approximately 52 per

cent. There are, however, certain aspects regarding the private sector companies

that need some discussion. Based on the performance index, the Annual Report 1998

(BSP 1999) has classified all the companies, including the GGC, into five categories,

ie A, B, C, D and E, The performance indicators are measured in terms of number of

plants constructed, average size of the plants, average defaults, average penalty and

feeding of the plants. For FY1997/98, the categories and the corresponding numbers

were as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Classification of the Companies and their Corresponding Shares in the

Total Plant Construction during FY1998/99

Distribution of

Companies by Type

Percentage of Plants Constructed by the

Companies by Category

Category

Type

Number ofCompanies

Percent

Number of PlantsConstructed

Per cent of thePlants Constructed

A Very Good 18 47 8 808 80

B Good 8 21 1 402 13

C Average 4 11 445 4

D Poor 6 16 333 3

E Very Poor 2 5 57

Total 38* 100 11 045 100

Sources: BSP 1999b and BSP.

* Data for BGG Company was not available.

This analysis has been carried out to indicate the quality of the plants constructed by theprivate companies that emerged in response to the privatization efforts made by the

sub-sector. The findings also indicate as to what extent the interests of the plant

owners as well as those of the exchequers are protected. The percentage of companies

falling into the very good and good categories was 68, while that belonging to the

average was 11. Similarly, 21 per cent belonged to the poor and very poor categories.

Now, in terms of percentage of the plants constructed by these companies, the very

good and good categories together constructed 93 per cent, while the average category

shared 4 per cent. Similarly, the poor and very poor categories shared 3 per cent of

the total. Now, if average is considered as within the acceptable range, then 97 per

cent of the plants constructed by the GGC and the private companies are within the

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

22/60

15

range of acceptance, and only 3 per cent calls for some corrective measures. Thus,

overall the performance of the companies involved in biogas can be considered to be

highly satisfactory.

Although one of the major factors attributable to the success of the biogas programme

in Nepal is the rational decision regarding its privatization (especially for the work of

plant construct ion), the rapid entry of a large number of companies rai ses somedoubts regarding their sustainability. At present, the companies are finding the

business lucrative because there are demands for the plants due to, on the one hand,

provision of subsidy and, on the other hand, the safeguarding of the interests of the

plant owners by the BSP through its quality control activities. Once the subsidy and

BSP are phased out, the companies will have to work under a perfect competitive

market, ie (a) in the absence of subsidy the demand for plants will decrease and their

corresponding shares in the market will decline; (b) in the absence of a strong

institutional mechanism to substitute the existing quality control work of the BSP,

credibility towards the mushrooming companies will diminish. In order to answer the

question: "Will all the companies working at present in the biogas sub-sector be able to

sustain their business after the subsidy and the BSP are phased out?," an attempt hasbeen made to measure their current strength in terms of their volume of business in the

sub-sector. Based on a recently concluded study (de Castro, et al 1999), it is assumed

that companies that are installing less than 100 plants per annum are either weak or

need a lot of efforts to sustain themselves. For analytical purposes, the companies that

installed less than 100 plants have been classified as small ones while those with 100-

500 plants and more than 500 plants have been classified as medium and large

respectively. The market shares of participating companies are given in Table 3.

Table 3: Market Shares of the Companies Participating in the BSP, FY 1998/99

Size of the Companies Number ofCompanies

Percentage

of

Companies

Total Numberof Construction

Percentage of

Total

Construction

500 Plants (Large) 5 13 6 453 58

Total 39 100 11 047 100

Source. BSP 1999b.

As can be seen from Table 3, of the 39 companies operative during FY1998/99, five

major companies were able to occupy 58 per cent of the market. Eighteen companies had

the market share of 35 per cent, the remaining 7 per cent being shared by 16 smaller

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

23/60

16

companies. This shows that despite the rapid increase in the number of companies the

main business is still in the hands of about 23 companies. The study also shows that

about 40 per cent of the existing companies were not breaking even in the business.

Moreover, two companies are reported to have exited from the business. It is likely that

more will do so in the near future.

In this regard, the findings of the mid-term evaluation of Phase III, Part I (de Castro, et al1999) has classified the companies into: (a) public sector companies (GGC is the only

public sector company owned by ADBN) (86% share) and Timber Corporation of Nepal

(TCN) (14% share); (b) private sector companies - (i) big players, (ii) small and medium

players, and (iii) 'fly-by-night operators'.

/. Public Sector: The GGC is the oldest company in the sub-sector. Its share has

gradually been decreasing over time (see Table I). The company has been passing

through a number of problems, including political interference, over staffing, high staff

turnover and lack of staff motivation.

2. The Big Players: This includes a small group of companies that have demonstratedrapid growth in their volume of business. This group, however, lacks required

managerial capability, as 'technicians' previously working with the GGC own most of

the companies.

3. The Small and Medium Players: This group also seems to have strong commitment toremain in the business. But, like their big competitors, they also have management

weaknesses.

4. The Fly-by-night Operators': The mid-term review draft has observed that there areseveral companies among the 39 recognized ones with very few staff and little office

facilities. They are believed to have been established to reap the benefits that they saw in

the business. They do not have long-term strategy and are likely to switch over to other

businesses once the sub-sector stops offering good opportunity, ie once subsidy and BSP

are phased out.

Mere establishment of companies does not ensure their sustainability. Sustainability in

simple terms can be defined as the capacity/ability of an organization that enables it to

continue even under an unfavourable situation. In case of most companies, the ability

seems to be lacking. Their volume of business as reflected by the market share is small;

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

24/60

17

managerial capability is weak; they are most vulnerable to the adverse situation of

subsidy phase out.

IV. BIOGAS QUALITY CONTROL:CURRENT PRACTICES AND ITS SUSTAINABILITY

Current Practices

Of the various factors attributable for the overall success of the biogas programme

in Nepal, the quality control implemented by the BSP, perhaps, has been

instrumental in achieving the current status of the programme to a greater extent.

Since its implementation, the BSP has paid special attention to ensure the quality

of the plants constructed under the programme. The objectives of the qualitycontrol programme are as follows:

Protect the interests of the plant owners. Ensure proper utilization of the subsidy. Enable the companies to become competitive and hence sustainable Level the playing field for the involved companies.Aspects of Quality Control

In order to achieve the stated objectives of quality control, the BSP follows the

following aspects of quality control:

Quality and Uniformity of Design

Although initially there had been some debate regarding the design of the biogas

plants, the BSP has adopted the GGC2047 model. All the companies wishing to

construct plants under the BSP projects are required to strictly comply with the

standard and failure to comply with the standard results in heavy penalty.

Quality of Construction

In order to follow the design, the construction needs to be based on the design and

all the materials need to be up to the specifications, such as size and quality of

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

25/60

18

bricks, rods, cement and sand. Use of sub-standard materials leads to heavy

penalty in the quality control check.

Quality of Operation and Maintenance by the Users

The masons during the construction give basic instructions on the maintenance of quality

of the operation and maintenance to the users. As the users gain experience over the first

six months of operation, they are further given a one-day training. So, the companies thatemploy untrained masons, who in turn are unable to instruct the users properly, which

would result in poor performance of the plant, would again invite a penalty.

Present Practices of Quality Control

Based on the annual programmes and budget of the BSP and the institutional capability

of the recognized companies, quota is fixed for the latter, for which the process is as

follows:

Agreement on Standard

The BSP and the companies first enter into a co-operation agreement containing area ofoperation, quota for biogas installation, plant sizing, subsidy and channelling

mechanism, after-sales and maintenance requirements, quality aspects, staff

development, reporting requirement, termination and suspension clauses. Then the

company also needs to enter into an agreement with the BSP. Plants that are constructed

outside the agreement cannot avail of the subsidy provided under the ongoing BSP

project. Under the agreement, the company should strictly follow that:

No family has more than one biogas plant. It offers guarantee for certain appliances and at the same time ensures after-sales

services, at least for six years.

Plant is not fed with night soil only. Design is based on the GGC drawing, 2047. All the construction materials are up to the standard. Construction is up to the engineering standard. All the fittings are properly done. After-sales services are carried out routinely as well as on as and when needed

basis.

Agreement on Penalty

Upon agreeing on the quality standard, the next agreement between the company and the

BSP is regarding the penalty to be paid by the former in case it fails to comply with all

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

26/60

19

or some of the covenants reached in the agreement. BSP thinks that the word 'penalty' is

not essentially a penalty.

It is just a mechanism to withdraw that part of the subsidy that has not been properly

utilized or in other words has been misused (Lam & Van nes 1994). The penalties

are based on the type of default. The defaults are broadly categorized into three:

Defaults causing withdrawal of all subsidies. Default causing a penalty. Defaults not causing a penalty. No default and improved performance earning a bonus.The defaults such as (i) construction of second or third plant in a family, (ii) plant owner

has no cattle/buffalo and the digester is fed with night soil only, (iii) no provision of the

one-year guarantee on appliances, (iv) absence of the six-year warranty on structure, (v)

lack of after-sales services for six years, (vi) plant constructed by untrained/uncertified

masons, and (vii) design not consistent with the GGC2047 are liable to be barred from

subsidy. Similarly, defects in the construction materials and appliances as well as errors

in construction lead to penalty. Defaults that are not liable to penalty include aspects

regarding the construction materials and construction that are less serious in nature.

Process of Quality Control

As per the agreement, the BSP carries out a detailed quality check of about 5 per cent

randomly selected plants. During this act, all the points related to the general

information, the specification of the plants, construction technique, operation, gas output

and so on are thoroughly verified by the BSP technicians who have been trained by the

expatriate and Nepalese technicians in this field. With a representative of the

construction company, the technical staff visit the sample plant and verify each point asoutlined in the agreement. Defaults are listed, discussed, agreed on right in the field so

that no controversy remains. Based on the default, penalty is calculated and charged to

the company, and deducted from the subsidy amount to be made available to it on behalf

of the plant owner.

Regarding the quality control activities, the mid-term review (de Castro, et al 1999)

observes that it has the following advantages and disadvantages:

Advantages

It allows a very high level of construction.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

27/60

20

Because of after-sales services provision, the operative continuity of the plant isensured.

It is used for the accreditation of the companies. Frauds regarding subsidy are minimized.

Disadvantages

Most of the companies still feel it as unnecessary imposition from the BSP. It is a very expensive procedure.Similarly, about the design, the mid-term review considers that because of the

standard, it has been less complicated. Had there been more than one design, the work

would have been rather very complicated. The one-model approach has greatly

simplified the work. It is, however, not devoid of criticisms. The main reason is the

blockage on the development of less costly technology. Experts believe that the

GGC2047 offers little chance for cost reduction. In this regard, the mid-term review

1994 (HMGN/SNV-Nepal 1994) has made some recommendations, which are still

valid. The mid-term reviewstates:

Biogas plants being installed in Nepal as part of the BSP are of fixed dome type having a

fiat cement concrete bottom/floor, a brick or stone masonry cylindrical tank and a

dome shaped cement concrete roof an inlet pipe connecting the digester with

feeding tank and a rectangular outlet tank. The fact that cement concrete and brick

masonry structures have much lower tensile strength than their compressive strength

indicates the possibility of either making the biogas plants stronger or reducing their

costs by employing shell structure for the digester and gas storage (the so-called

Deenbandhu model). A few plants of this design that have been developed in India

having segments of two spheres of different radii of curvature joined at their base to

form the digester and the gas storage have already been ins tal led in Nepal by an

NGO (South Asia Partnership-Nepal) atlower costs.

. . Sustainability

Undoubtedly, the adoption of the one-model approach by the BSP has simplified the

process of quality control in reaching the present status to a great extent. The model has

helped in establishing uniform standard and norms to be followed by all the players in

the sub-sector. It can be considered as a very prudent measure in the beginning. Had

there been more than one model, the quality control process would have been

rather cumbersome and more expensive than the present one.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

28/60

21

The model, however, is considered to be more expensive as compared to one

mentioned above. Failure to offer alternative to this model could considerably reduce

the demand in future once the subsidy is phased out and the richer strata of the

population are saturated with biogas plants. Studies show that unti l now, almost al l

of the plant owners belong to economically richer strata of society (CMS 1999; Dev

part 1998; East Consult 1994; Lam & Van nes 1994). And, there is nothing wrong with

this result. It is quite in concert with the stated objective of the biogas programme, iecheck the environmental deterioration by substituting fuelwood, agricultural waste and

dung cake to meet the rural energy deman d. Th e pro gramme is nota nd should no t

be as long as th ere is enough demandpoverty-oriented. At the same time, the

BSP a lso has a very important objective of developing the biogas as a market-oriented

viable industry. This means, all the interventions, ie subsidy and external assistance,

would cease sometime in future. This would increase the cost of the GGC2047 model,

considered to be already expensive and out of the reach of the poorer strata of the

population.

In order to make the present biogas programme sustainable, there is needed some R&D

work so that the technology becomes cheaper and within the access of the poorer peoplein the rural area.

V. SUBSIDY, ITS ROLE IN PROMOTION OF BIOGAS PLANTS,

PLAN FOR PHASING AND POSSIBLE EFFECTS THEREAFTER

Quality control work and subsidy on investment combined with privatization of the plant

installation are considered to be three major factors contributing to the overall

development of the biogas sub-sector.

History of Subsidy to Biogas Plants

Application of definitional subsidy to the biogas plants began in the Agriculture Year

(1975/76) when the government provided interest-free loans to about 290 plants.

Similarly, in FY1983/84, an incentive of Rs5,500 per plant was provided under special

rice crops launched in four Tarai districts2. Planned efforts to develop the biogas

beganfrom the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1985-1990) when some 4,000 plants were

planned for the plan period and 25 per cent subsidy on investment and 50 per cent subsidy

2 In order to promote the biogas, it was a linked up with the special rice crops in the four

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

29/60

22

on interest were provided. This, however, was implemented only during the last two

years of the plan period. The subsidy on capital investment received continuity

after the implementation of the BSP.

Economic Rationale for the Subsidy

The economic rationale for any subsidy scheme for production of goods and services liesin the benefits that accrue to society as a whole from the activities undertaken. Because

of the existence of price distortions and lack of perceived benefits from the goods and

services, private benefits fall below the social benefits and do not become attractive to

the private entrepreneurs, while from the social point of view, production of such goods

and services yields benefits exceeding the costs and becomes desirable for society as a

whole. Such activities require external inducement so that the private sector takes up the

activity and the social benefits are maximized. In case of biogas, the economic rationale

for the subsidy was investigated in a study conducted in 1991 (Silwal 1991). As usual,

the presence of price distortions, absence of perceived benefits, such as the value of the

increased nutrients content from the slurry obtained from the digester, resulted in

financial internal rate of return (FIRR) lower than the prevailing market rate of interestand an economic internal rate of return (E1RR) higher than the social opportunity costs

of capital, which justified the subsidy. Another study, which was conducted to evaluate

the effectiveness of the ongoing subsidy, came up with the following findings and

recommendations (Silwal & Pokharel 1995):

Due to the presence of a distortive pricing mechanism and lack of perceivedbenefits, FIRRs for all sizes of the plants were lower than the market rate of interest.

The prevailing rates of subsidy (Rs7,000 in the Tarai and Rsl0,000 in the hills)resulted in FIRRs ranging from 15.89% to 33.35%.

The average E1RR for all sizes was 23.82% and hence the subsidy wasrationalized.

In addition to rationalizing the ongoing subsidy, the study also recommended one more

subsidy to the inaccessible hill districts at the rate of Rs 12,000 per plant.

Similarly, a recently conducted study (Kandel 1999) has the following findings:

districts of Terai.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

30/60

23

The EIRR is higher than the FIRR mainly because of the subsidies on kerosene andurea, and the low pricing of firewood.

The other benefits that are s ti ll missing in the private benefits stream are the healthbenefits accruing from the use of the biogas.

The benefits accruing from the improvement in health, however, are not easy to quantify.

Both the studies have strongly rationalized the subsidy.

Impact of the Subsidy on Installation of Plants

The impact of the subsidy on increasing the number of plants has been remarkable. Even

before the BSP was implemented, the subsidy showed its distinct role in the promotion

of the biogas, ie there was direct correlation between the number of plants installed and

the provision of subsidy. Table 4 shows the impact of subsidy on installation of the

biogas plants before the BSP.

Table 4: Biogas Plants Installed under Various Subsidy Schemes

by YearYear Up to

85/86

86/87 87/88 88/89 89/90 90/91 91/92 92/93

Number of

Plants

2 166 405 676 1 108 1 403 862 2 304 4 173

Source: BSP.

As can be seen, there was a gradual increase in the number of plants installed over time,

for during this period there was some type of subsidy except during 1990/91 when a

capital subsidy of 25 per cent was provided on plants of 6 m 3 and 10 m3 only. Then,

from 1991/92, the number of plants installed picked up as the newly elected

government of the Nepali Congress announced the subsidy at the rate of Rs7,000 for

Tarai andRsl0,000 for the hills. In this way, the present programme is a subsidy-driven

one. With the implementation of the BSP and continuation of the subsidy, the effect has

been quite satisfactory.

Besides the increase in the number of plants over lime, another desirable impact of the

subsidy has been the tendency towards installing plants of smaller sizes. Because of the

flat rate for a particular geographical region, ie Rs7,000 in the Tarai, Rs10,000 in the

hills and Rs 12,000 in the hilly districts not connected with road, the plant owners have

been found to be inclined towards installing smaller plants as this reduces the ir

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

31/60

24

costs considerably. For instance, the average size of plants during 1989/90 was 13.7 m ,

which decreased to 9.6 m3 during 1992/93 and further declined to 8.2 m3 during 1996/97

(de Castro, et al 1999).

The current subsidy scheme, however, is not without defects. For instance, all the

villages of Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Lalitpur receive subsidy at the rate of Rs7,000

whereas Pokhara receives Rsl0,000. This is reported to be discriminatory against thepeople of remote areas of the former districts (there are places in Lalitpur requiring two

to three days of trekking).

Plan for Subsidy Phase-out

The general policy of the government has been to phase out all the subsidies that are

currently in effect. In this regard, subsidies on fertilizer and irrigation have been reduced

considerably. As to the biogas subsidy, no timeframe has been laid down for the phase-

out. The mid-term review (de Castro, et al 1999) considers that the present level of

subsidy is reasonably high enough to attract the users who have not yet perceived the

benefits. Once they perceive the benefits, the programme can keep on going even when

subsidy is gradually phased out. The subsidy rates for 1999/2000 for all the three

geographical regions are shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Subsidy Rates for 1999/2000 (2056/57)

In Rs

Size (cu.m.) Tarai Hills Remote Areas

4 7 000 10 000 12 000

6 7 000 10 000 12 000

8 6 000 9 000 11000

10 6 000 9 000 11 000

15 and 20 No Subsidy No Subsidy No Subsidy

Source: BSP.

In terms of discouraging larger sizes, the implementation would be able to achieve itsgoal to a great extent. This will minimize the current problem of underfeeding of the

plants, which is reported to be very common among the larger plants. Better-off farmers

consider the larger plants as status symbol and insist on installing them despite the limited availability of dung that they get from their animal stock. It must, however, be

noted here that the amount of subsidy for the larger sizes and invariably installed by

bet ter-off farmers will be so small and meaningless that they would hardly opt for it.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

32/60

25

Instead, they would construct from their own resources, including bank finance. In this

case, they will be out of the quality control fold and the market may be distorted beyond

control. Instead of provisioning very little for the larger sizes, it would be better to ban

altogether installation of plants of sizes of 15 m3 and 20 m3. Then the four sizes, ie 4 m, 6m3, 8 m3 and 10 m should get the flat rate of subsidy as at present. This arrangement

would natural would naturally bring down the average size to less than 8 m3, which is

the target of the present BSP.

In the context of the government policy of gradual phase-out of the subsidy for all the

sectors of the economy, it would be very rational on the part of the biogas programme to

formulate a policy of phase-out by certain period of time. The timeframe would provide

time for preparation for all the stakeholders.

Possible Effects of the Phase-out of the Subsidy

As no timeframe has yet been decided for the phase-out, it would be premature to assess

the impact of the phase-out. No matter what timeframe is decided, the reduction/phase-

out of subsidy in the absence of proper R&D leading to cheaper technology, ie

considerable reduction in the existing costs of biogas plant, could adversely affect thebiogas sub-sector, especially in terms of demand. If the mid-term review-recommended

reduction of subsidy is implemented, it would reduce the demand for the biogas plants.

A total phase-out would further decrease the demand. So, the phasing out should not be

implemented before models of technical competence and lower costs are developed.

VI. FINANCING OF BIOGAS

Biogas installation, under the current technology, is not a cheap proposition. A typical

costs structure trend for a 10 m biogas plant over a period of six years is given in Table

6.

The figures are for the total costs. The sources of financing these costs are three:

equities, subsidy and loans from the ADBN. Some farmers may bear some costs in the

form of equities, while others may prefer to borrow all the costs less the subsidy from

the banks. Table 7 provides information on the amounts of equities, subsidy and loans

for all the three phases of the BSP.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

33/60

26

Table 6: A Typical Costs Structure Trend for a 10 M Biogas Plant

(1991/92-1996/97)

InRs

Item/Year 91/92 92/93 93/94 94/95 95/96 96/97

To be managed by farmers

Cement 4 180 4 180 3 990 4 465 5 320 6 080

Other building materials 5 500 5 500 5 500 5410 6 340 8315

Unskilled labour 1575 1 575 1 575 1 575 2 100 2 100

To be managed by company

Pipes and appliances 4 696 5 277 4 945 5 070 4 696 5 460

Overhead + 1 year service 3 950 3 950 3 950 4018 4 600 4 800

Additional service period 1 150 1 150 1 050 1 000 1 000 1 500

Total 21 051 21 532 21 185 21 713 24 056 28 255

Source: Van nes 1997.

Table 7: Finance and Financing Sources for the Biogas Plants

Constructed under BSPIn Rs Million

Phase Phase I Phase II Phase III Part 1

Year Equities Subsidy Loans Equities Subsidy Loans Equities Subsidy Loans

1992/93 2.56 28.60 49.38

1993/94 6.20 30.48 37.64

1994/95 14.90 44.17 53.95

1995/96 29.96 61.86 77.96

1996/97 11.85 10.04 5.77 51.00 63.27 90.17

1997/98 74.00 84.96 120.88

1998/99 80.00 94.27 129.94

Notes: (I) Equities calculation is based on actual cash/loan shares and assumption of net cash

investment being approximately 85% of net loan investment.

(2) Subsidy calculation represents actual subsidy expenses.(3) Loan calculation is based on average estimated net loan amount by ADBN of NRs 20,667

per plant and actual loan/cash shares in production.

Source: Castro, et al 1999; Van nes 1997;BSP.

In the first year of Phase I, the total investment was Rs80.54 million, of which 3.17

per cent was financed from the equities, and subsidies and loans contributed to 35.5

per cent and 61.30 per cent respectively. In the second year of Phase II of the BSP,

the total investment amounted to Rsl69.78 million. Of this, 17.64 per cent was

equities financed, and 36.43 per cent and 45.91 per cent were financed from

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

34/60

27

subsidies and loans respectively. Similarly, in the third year of Phase III Part I,

the total investment was Rs.5304.21 million, of which 26 per cent was financed from

the equities, 31 per cent and43 per cent from the subsidies and loans respectively.

Thus, over the three phases of the BSP programme, the share of equities has increased

while the shares of subsidies and loans have declined. The analysis on the financing

discussed so far is based on the amount of finance from different sources. In order to

assess the percentage of plants that have been financed from the different sources,Table 8 has been constructed.

Table 8: Percentage of Solely-Equities Financed and Equities and

Loan Financed Plants

In per

cent

Year/Types Solely Equities-financed Equities- and Loan-financed

1992/93 6 94

1993/94 16 84

1994/95 23 77

1995/96 30 70

1996/97 40 60

1997/98 42 58

Source: Castro, et al 1999; Van nes 1997.

Being applicable to both the categories, ie equities-financed and equities plus loan-

financed, all the plants are subsidized and hence there is no need to indicate them

separately. Regarding solely equities-financing, the trend is quite impressive. There has

been a general tendency towards financing the plant from equities plus subsidy. Loan

does not seem to be a constraint for the plant owners (CMS 1999; Devpart 1998; East

Consult 1994; Lam & Van nes 1994). Moreover, since the second phase of the BSP,besides ADBN, NBL and RBB also are providing loans. On the repayment front also,

the performance is reported to be satisfactory.

ADBN, being the pioneer of biogas promotion in Nepal, is still found to be the most

favoured source of credit, and over 90 per cent of the loans to the biogas are disbursed

through this bank. Despite the higher rate of interest charged by the ADBN (16%),

plant owners preferred to have loans from it than from NBL and RBB, which charge

11.5% and 15% respectively. The latter two are relatively new in this field and have to

establish themselves as friendly banks among the rural borrowers, especially in case of

biogas loans.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

35/60

28

VII. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

The first institutional set-up for the promotion of biogas technology began with the

establishment of the GGC, an undertaking of the ADBN, TCN and UMN, back during

1976/77. Over time, there has been a gradual growth in the institutional aspects, Besides

the BSP, the following types of institutions are involved in the biogas sub-sector:

Biogas Companies

On the supply side of biogas, the companies are the major stakeholders operating as a

business entity in a competitive manner. With the implementation of the BSP, there has

been a steady increase in their number. Table 9 provides information on the number of

companies working in the biogas sub-sector.

Table 9: Trend in the Entry of Companies

In Number

Year Working with BSP Working outside BSP

Phase I

1992/93 1 6

1993/94 1 10

Phase II

1994/95 17

1995/96 23

1996/97 36

Phase III

1997/98 41

1998/99 391999/00 50

Source: BSP.

The number of companies at present is 50, including the GGC. One of the guiding

objectives of the privatization of the sub-sector has been to bring in private companies

working in a competitive way so that the potential plant owners have a choice in

constructing the plants from the company they consider appropriate. This objective

seems to have been met to a great extent.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

36/60

29

Weaknesses and Problems of Companies

Except the GGC, which has been in the business for more than 20 years, the

emergence of private companies is relatively new. When staff working in the GGC

saw an opportunity in the sub-sector, they decided to form companies in line with the

BSP requirements. Similarly, the private companies also started losing some of their

staff and workers, who, after working for sometime in the companies they wererecruited, saw it more profitable to establish their own companies. In this way, most of

the staff and workers of the existing companies have had some links with the GGC or

the private companies established in the beginning. And there does not seem to be

anything wrong about it. In an open and democratic society this is a proper way of

developing institutions. These companies, however, are reported to be facing the

following problems at present (Castro, et al 1999; Van nes 1997):

' : -

Biogas Companies in General

One problem of biogas companies in marketing their product is the fierce competition.

Especially in the traditional biogas areas in the Terai (Bharatpur, Pokhara, Butwal)

where a relatively high number of biogas companies are operating in an increasinglysaturated market, this has in a number of cases led to unhealthy and intolerable practices.

Examples documented are companies slandering each other, robbing of loan applications

submitted to the bank by another company, up to the point where the farmer has been

pursued to change company after construction has commenced.

Another serious problem is the weak liquidity position of many companies, hampering a

smooth and continuous operation. The capital base of many (smaller) companies does

not allow taking loans from banks, and even larger companies are found to be unable to

obtain adequate loans to cover their working capital requirement. The new subsidy

channelling procedure, introduced with the start of FY2056/57, is aggravating this

problem. SNV/BSP, recognizing the dilemma, is therefore with the star t of this fiscal

year providing working capital to companies. The eligible amount depends on the

preceding year's production of the company in combination with its performance

quality, and companies are required to cover the advance with a bank guarantee.

Despite being the oldest company, the GGC has been facing a series of problems. One of

the serious ones has been the frequent change in the chief executive. Other problems

include bureaucratization, overstaffing, high turnover of the staff and lack of staff

motivation.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

37/60

30

The steady slide in the market share is a clear indication of the problem (see Table 1)

Association of Biogas Companies

Nepal Biogas Promotion Group

An entity, namely the Nepal Biogas Promotion Group (NBPG), consisting of

representatives of all the biogas companies, was established in the year 1995. Since it

was a democratically established entity for promoting the biogas technology and at the

same time protecting the common interests of its members, the move was very much

welcomed from all corners. Some of the identified activities for the NBPG include: (a)

facilitate the import of biogas appliances, (b) solve the problems with the banks, (c)

avoid unhealthy competition among the member companies through preparation and

implementation of a code of conduct, (d) gradually take over the activities of the

promotion of biogas, training and extension activities being carried out by the BSP.

Because of a serious division among the members, since not very long after its

establishment, the organization has shown little performance; staff is not empowered

adequately and lack desired level of dynamics (Van nes 1997). Strengths of the NBPG

include: (a) it is recognized as an agency by the AEPC, BSP and other related agencies,

(b) it has been associated with BSP and has received technical assistance for its

institutional capability building, (c) it has a separate secretariat manned by full-time

staff, (d) it has initiated some of the work of BSP such as quality control and after-sales

services, (e) its membership is larger than that of AEPDF, and (f) it has aimed at gaining

Financial autonomy through import of some appliances, membership fees and

consultancy services.

As discussed above, the organizations also have certain weaknesses, which is likely to

threaten their sustainability. They are: (a) clash of interests among the members has

already resulted in its downsizing through division, which may occur in the future aswell, and (b) it lacks trained manpower and other necessary facilities to take up the work

of quality control and after-sales services and at the same time run the group as a

business entity.

Alternative Energy Promotion and Development Forum (AEPDF)

Although it would be premature to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of this new

entity at this juncture, some of these aspects have been outlined by the mid-term review.

On the strength front, the organization is reported to have been able to attract over 30

companies out of 50 working in the sub-sector up to 1 November 99. It has also indicated

some possibility of working in the field of biogas promotion, training and even some

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

38/60

31

quality control work. Regarding the weaknesses, prominent one is its dispute with the

NBPG. Another serious weakness is the 'dual loyalty' of its members, ie members of this

organization are also the members of the NBPG.

Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC)

Based on the mid-term evaluation (mid-term review), May 1994 (HMGN/SNV-Nepal

1994), which recommended that "HMGN should establish as soon as possible an apexinstitution for the development of the biogas sector. As long as such an institution is not

established, ADBN and SNV/Nepal should work closely together for the implementation

of the Programme,' after much discussion and debate, the Ministry of Science &

Technology in August 1996 formed the Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC)

under the Development Board Act. As the name implies, it is related to all the alternative

energy sectors, including biogas. The AEPC's functions include the following (HMGN

& SNV 1995):.

Analysis of policy issues and advice on policy matters. Co-ordination with other sectors and ministries. Preparation of sector-wise plans and targets. Elaboration of regulatory frameworks: setting of standards and guidelines, criteria

for registration and licensing of companies.

Mobilization of funds and liaison with donors. Review/approval of annual work plans in respect of donor-funded projects in

alternative energy.

Monitoring of development in the alternative energy sector as a whole. Organize and/or participate in programme and project evaluations.A recent evaluation (de Castro, et al 1999) shows that being an entity established under

the Ministry of Science & Technology and funded by the government, it has a number of

advantages in becoming an effective organization for the promotion of alternative energy

in the country, including biogas. On the strengths of the organization, the noteworthy

aspects include: (a) government's commitment is reflected through its provisioning of

budget for the operation of the centre, (b) being a new entity, it does not have a history

of incompetence, (c) all stakeholders have recognized it as a national body for policy

formulation, (d) it has gradually started taking up some of the BSP's work like some

quality work and monitoring and evaluation, (e) it has qualified and competent staff to

run the centre, (f) being a government undertaking, it has easy access and links with the

NPC, l ine ministry and donors, which other stakeholders do not have, (g) it has recently

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

39/60

32

entered into an agreement with DANTDA for institutionalization and capacity building of

the AEPC so that it can take up more and more responsibilities in future, (h) it has the

potentiality of attracting more donors in future.

It is also not without weaknesses. They include: (a) being a government undertaking, it

needs to comply with the rules and regulations that are not flexible enough to allow it to

run the centre, (b) like other government organizations, it may face political interference,(c) the low salary and incentive structure may cause high turnover.

Institutionally, the biogas sub-sector cannot be considered as a strong one. Leaving the

BSP aside, it remains with three organizations, ie AEPC, AEPDF and the NBPG, which

have not been able to demonstrate the desirable capacity. The BSP is just a project office

and temporary in nature, which will be phased out in future. At present, it has been

playing a vital role in the promotion of biogas in the country. It initiated, designed and

got government approval on a number of policies, including the subsidy and the

privat ization. It has been implementing the most acclaimed work of quality control,

which has been a key to the overall success of the biogas programme. Once the BSP is

phased out, there needs to be a strong entity to take up the work of policy formulation,

regulation, and monitoring and supervision.

VII. IMPACT OF BIOGAS PLANTS

The BSP, through its consultants, conducts periodic surveys of the users. The main

objectives of the surveys are to assess the overall impact of the biogas plants, mostly in

terms of fuelwood and kerosene saving, saving on time that would have been required

for collection of fuelwood and cleaning of utensils used for cooking in fuelwood in the

absence of the plants. In order to know the impact of the biogas plants on its users, five

studies have been found to be relevant. Their findings are summarized as follows:

The User Survey 1994 (East Consult 1994) conducted in the year 1994 revealed the

following 'other' benefits that were reported by the users, among others:

On an average a plant saved an equivalent of 3 metric tons (MT) of fuelwood and

40 litres (It) of kerosene annually.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

40/60

33

Time savings from the collection of fuelwood and cleaning of utensils averaged 3.10hours per day.

Respiratory diseases very common among the fuelwood users were reported to below among the biogas user households.

Some of the recommendations made in the study are:

Increase the frequency of training of construction masons and operation andmaintenance (O&M) training to the users.

Improve the after-sales services. Introduce a consistent policy to incorporate small and marginal farmers in the biogas

programme.

Provide additional subsidy to cover extra transportation costs in the far and remote

areas.

Conduct research to ensure adequate gas generation during the cold season. Induct other banks to disburse biogas loans. Conduct R&D to replace the concrete dome in the hills.Similarly, the 1995 survey (Lam & Van nes 1994) revealed the following impact:

The majority of the biogas owners were medium or large farmers. As against the national literacy of 40 per cent, literacy among the plant owners was

80 per cent.

On an average, use of biogas saved 3.5 MT of fuelwood and 56.6 It of kerosene perplant per annum.

More than half of the plants were underfed, ie there was no sufficient dung to putinto the plants.

It recommended:

GGC's after-sales services should be enhanced3. Masons should not be allowed to construct too many plants. GGC should open branch offices to provide services to the potential owners. ADBN's practice of charging interest on subsidy until it is adjusted in the

borrower's account should be discontinued.

User training should be initiated.3 Until this survey, the sample included plants constructed by the GGC only.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

41/60

34

Provision of incorporating small and marginal farmers should be introduced.Similarly, the User Survey 7998 (Devpart 1998) reported the following findings:

Unlike the findings of the previous survey, the users also consisted of a few smalland marginal households.

Literacy among the plant owners was 77 per cent.

In all 36 per cent of the plants were attached with latrines. The O&M services provided by the construction companies were considered to be

satisfactory in most of the cases.

Altogether 68 per cent borrowed from the banks (64 per cent from ADBN, 4 percent from RBB) and the rest constructed on cash down payment.

Compared to other types of loans, the repayment of biogas loans was good. Saving of fuelwood and kerosene was reported to be 1.6 MT and 24 It respectively.Recommendations made by the same survey are:

For maintaining the current reliability and efficiency of the biogas plants, BSPshould continue the current practice of monitoring.

Social awareness programme is necessary to maximize the social benefits from theplants.

For maintaining the current reliability and efficiency of the biogas plants, BSPshould continue the current practice of monitoring.

Efforts to downsize the plant should be continued so that cases of underfeeding areminimized.

Problem of after-sales services could be minimized by the companies throughinvolvement of local NGOs.

The BSP should consider inducting the staff of government line agencies so thatthey can participate actively.

The User Survey 1999 (CMS 1999) reported the following findings:

The literacy rate of the sample households was about 75 per cent. Altogether 69 per cent of the plant owners used dung as the primary feeding material

for bio-digester and 27 per cent of the plants were attached with latrines.

In all 77 per cent of the plants were installed for cooking conveniences due toshortfall of fuelwood.

A total of 86 per cent of the users reported of sufficiency of gas for cooking andlighting.

Quality control was found to be satisfactory by about 95 per cent of the plantowners.

-

7/29/2019 Review of Bsp Nepal 1999

42/60

35

Altogether 48 per cent were found to be using the slurry after making compost. About 98 per cent of the plant users reported to have savings on time after the use of

biogas.

Decrease in respiratory diseases by 53 per cent was reported. Approximately 55 per cent expressed their satisfaction over the bank loan

procedures.

Surprisingly, the latest survey has not quantified the amount of fuelwood and kerosene

saved from the use of biogas plants.

From all these findings, it can be safely concluded that biogas has been a very useful

technology that has impacted the life of its users in a positive way.

IX. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Summary

History of Biogas and Advent of BSP

Although the history of biogas in Nepal dates back to 1955, HMGN's efforts began only