Report 102

-

Upload

crooksta543 -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Report 102

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

1/68

INEF-Report102/2011

Institute for Development and Peace

Assessing HumanInsecurity Worldwide

The Way to A Human (In)Security Index

Sascha Werthes/Corinne Heaven/Sven Vollnhals

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

2/68

NOTEONTHEAUTHORS:

Sascha Werthes (Dipl.Soz.Wiss.), lecturer at the University of DuisburgEssen. Associate

FellowattheInstituteforDevelopmentandPeace(INEF)attheUniversityofDuisburgEssen.CoordinatoroftheWorkingGrouponHumanSecurity(AGHumanSecurity).Ph.D.candidateattheCenterforConflictStudies(CCS)atthePhilippsUniversityMarburg.

EMail:[email protected]

CorinneHeaven (Dipl.Pol.),Ph.D.Studentat theUniversityofReading.AssociateFellowattheInstituteforDevelopmentandPeace(INEF)attheUniversityofDuisburgEssen.

EMail:[email protected]

Sven Vollnhals (Dipl.Soz.Wiss. Cand.), studies political science and economics at theUniversityofDuisburgEssen.MemberoftheWorkingGrouponHumanSecurity(AGHumanSecurity).

EMail:[email protected]

BIBLIOGRAPHICALNOTE:

SaschaWerthes/CorinneHeaven/SvenVollnhals:AssessingHuman InsecurityWorldwide:TheWay toAHuman (In)Security Index. Institute forDevelopmentandPeace,UniversityofDuisburgEssen(INEFReport102/2011).

Imprint

Editor:

InstituteforDevelopmentandPeace(INEF)

UniversityofDuisburgEssen

Logodesign:CarolaVogel

Layoutdesign:JeanetteSchade,SaschaWerthes

Coverphoto:JochenHippler

InstitutfrEntwicklungundFrieden

Lotharstr.53 D 47057Duisburg

Phone+49(203)3794420 Fax+49(203)3794425

EMail:[email protected]

Homepage:http://inef.unidue.de

ISSN09414967

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

3/68

SaschaWerthes/CorinneHeaven/SvenVollnhals

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

TheWaytoaHuman(In)SecurityIndex

INEFReport102/2011

UniversityofDuisburgEssen InstituteforDevelopmentandPeace

UniversittDuisburgEssen InstitutfrEntwicklungundFrieden(INEF)

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

4/68

ABSTRACT

SaschaWerthes/CorinneHeaven/SvenVollnhals:AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide:

TheWaytoAHuman(In)SecurityIndex

The ideaofhuman securityhasbeenpresentedanddiscussed in internationalacademicand

political fora formore thanadecade.Yet,despite itspopularity, theanalyticalusefulnessas

wellasthepoliticalappropriatenessoftheconcept isfrequentlycriticized. InarguingforandpresentingaHuman(In)SecurityIndexweaddressbothaspects.

In the firstpart,wediscuss the ideaofhumansecurityand introduce thereader to themain

critiqueregardingtheconceptualusefulnessofthe idea.Secondly,wereflectonthecontested

developmentsecuritynexuswhenpresentingourconceptualframework.Additionally,weput

forwarda thresholdbasedconceptualizationofhuman securitybasedon the ideasoriginally

presentedby TaylorOwen togetherwithMaryMartin. To substantiate the thresholdbased

conceptualizationwepresentamultidimensionalHuman(In)SecurityIndex,allowingtoassess

respectivelevelsofhuman(in)security.Byoperationalizingthedimensionsofhumansecurity

andpresentingavailabledatafor2008,oneoftheremainingconceptualchallengesisaddressed.

WedemonstratehowaHuman(In)SecurityIndexcanbeusedinthepoliticalrealmandbring

to thefore thepotentialcore threats tohumansecurity.Thisadditionallyspecifies the ideaofhuman security and furthers a differentiation between human security and other related

conceptssuchashumandevelopmentandhumanrights.

Insum,wearguethathumansecurityasapoliticalidearemainshighlyrelevant.Asapolitical

leitmotif, human security is significantly and constructively used and applied in political

processesdespiteorbecauseofitsanalyticalambiguity.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

TrotzdervielfltigenAufmerksamkeitdiedasKonzeptdermenschlichenSicherheiterfahren

hat,sobleibtesdochinvielerleiHinsichtumstrittenundkritisiert.EinerzentralenKritik,dass

dasKonzeptempirischanalytischproblematischundmenschlicheUnsicherheit letztlichnicht

erfassbar sei, widmet sich dieser INEFReport. In einerWeiterentlicklung von Ideen von

TaylorOwen und TaylorOwen zusammenmitMaryMartin entwickeln dieAutoren einen

innovativenAnsatzmit dem sichmenschliche Sicherheit zumindest auf lnderspezifisch in

verschiedenenDimensionenerfassen lsstund leistenhierdurch einenwichtigenBeitragwie

das Konzept menschlicher Sicherheit auch fr die Zukunft politisch nutzbar als auch

akademischfruchtbargenutztwerdenkann.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

5/68

Content

1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 52. HumanSecurity:TheOriginalApproach,ConceptualChallenges,

andPoliticalConsequences......................................................................................................... 62.1 ConceptualChallenges...................................................................................................... 82.2 DifferentSchoolsofHumanSecurityandTheirPoliticalImpact................................92.3 FindingAnswers:AddressingtheDevelopmentSecurityNexus.............................12

3. AddressingtheChallenge:AHuman(In)SecurityIndex....................................................163.1 PreliminaryRemarksontheHuman(In)SecurityDimensions.................................193.2 Methodology:ComputationoftheHuman(In)SecurityIndex..................................253.3 Findings............................................................................................................................. 28

3.3.1 HumanEconomic(In)Security....................................................................... 283.3.2 HumanFood(In)Security............................................................................... 293.3.3 HumanHealth(In)Security............................................................................ 313.3.4 HumanEnvironmental(In)Security.............................................................. 343.3.5 HumanPersonalandCommunity(In)Security...........................................343.3.6 HumanPolitical(In)security...........................................................................353.3.7 HumanInsecurity............................................................................................ 38

3.4 ADescriptiveAnalysisoftheHuman(In)SecurityIndexwithotherIndices...................................................................................................................... 41

4. Rsum........................................................................................................................................... 42

5. References..................................................................................................................................... 45

6. Annex1:CountriesinAlphabeticalOrderandScoreforallDimensions........................51

7. Annex2:CountriesRanked....................................................................................................... 57

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

6/68

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

7/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

5

1. Introduction1The

notion

of

human

security

has

strongly

influenced

the

academic

and

politicaldebatealike.Asmuchastheusefulnessoftheideahasbeencontested,asmuchithasbeenlobbiedfor.Notwithstandingtheideaspoliticalimpactthecritique raised is substantial: it is said tobe too vague, too ambiguous, tooconceptuallyweaktonameonlyafewpointswhichhavebeenargued.

Thefollowingpapertakestheseanalyticalchallengesasastartingpointandresponds to one of themajor conceptual questionsby presenting aHuman(In)Security Index. The paper is organized in three parts: Chapter 2brieflysketchesouttheoriginalapproachtohumansecuritybytheUNDPandoffersabriefoverviewonthecurrentdebateaswellasthesubsequentcriticismraised.Despitethecriticism,thenotionofhumansecurityhasgainedpoliticalimpact.

Humansecurityhasgatheredfriendsandsomecountrieseventurnedtheideainto a guiding principle for their foreign policy agendas. Substantial policyresultshavebeenreached. Inchapter3wesuggestawayhow toaddress theproblematic close linkages to related concepts such as human developmentandhuman rights.Weproposea conceptualandpolicy frameworkbasedonthe ideas developed by Pauline Kerr. This helps to substantiate thedevelopment of actual thresholds which are also elaborated in chapter 3.Furthermore,inchapter4weexplicitlyaddressoneoftheremainingchallengesup to today.As iswell known, it haswidelybeen argued that the contextspecificanddynamicnatureoftheideaofhumansecuritydoesnotallowforameasurement of the potential insecurity of human beings. This makes

impossibleaprioritizationofpoliciesoreventoevaluatethesuccessofcertainpolicymeasures.Against thisbackground,we present an alternativeway ofoperationalizingtheideaofhumansecurity.AHuman(In)SecurityIndexhelpsto inform thepolitical realm in locating thehuman insecurityhot spots, thusenabling policy makers to set priorities and also to evaluate their policyinitiatives. Some of our findings of our assessment of human (in)securityworldwidearepresentedinchapter4andarebrieflyillustrated.

Importantly, one has to emphasize that a Human (In)Security Index iscertainlynomeaningfulsubstitute foran indepthanalysisofcountryspecificsituationsor the situationof thepopulation.However,aHuman (In)SecurityIndexisvaluableandhelpfulforatleastfivereasons:

a) It helps to present global trends in the respective human securitydimensions.Although there is a number of global indices (BertelsmannTransformation Index;HumanDevelopment Index;Global Peace Index;FailedStateIndex,tonameonlyafew),noneofthem,atleastuptonow,adequatelyrepresentsthehumansecuritysituationastheyareconstructed

1 Amongmanyotherswe aregrateful to StephaneRoussel,ChristianBger,DanielLambach,CorneliaUlbertandFelixBethkefortheirhelpfulcommentsandcriticalreviewofthefirstdraft.Moreover,wewouldliketothanktheWorkingGrouponHumanSecurityanditsmembersfortheircontinuousandenthusiasticsupport.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

8/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

6

fordifferentpurposes.Therehavebeenotherattemptstoassessthehumansecurity situationworldwide (e.g. theHuman Security Index)2,but theyaddress the issue from a different analytical perspective and mainlyconcentrateonsubstantiatinghumansecurityviaanequitabilityenhanced

HumanDevelopmentIndex.b) Bydescribing thehuman insecurity situation in the respective countries

from abroad general dimensional perspective, it is illustrated inwhichhuman(in)securitydimensionscountriesperformquitewellandinwhichnot. Thereby, the possibility to set priority agendas for policy action isoffered.

c) The Human (In)Security Index helps to substantiate aggregatedthresholds of human insecurity in the respective human insecuritydimension.

d) Inthelongrun,theHuman(In)SecurityIndexshouldalsohelptoassessin

whichdimensionrespectivecountrieshavemadeprogress,thatis,performbetter than before. The index might measure the success/efficacy oreffectivenessofcertainpolicyinitiatives.

e) Finally,onecanarguethatnocountrywantstobeseenasabadperformerwhen it comes tohuman security.TheHuman (In)Security Indexmighthelpinfosteringthepoliticalwillintherespectivecountrybutalsointheinternational community to help the respective country to addresschallengesintherespectivehumaninsecuritydimensions.

Insum,wearguethataHuman(In)SecurityIndexcanperformasthebasisforproposinggeneralgoalsforpolicyprograms.Theindexshouldberegardedasa

reference base and starting point when it comes to the first phase ofoperationalizing the human security concept in theway theUnitedNationsTrustFund forHumanSecurity (2009)hasproposed.Additionally,onamoregeneralandbroadlyaggregatedlevelitoffersthepossibilitytosubstantiatetheideaofhumansecurityanditsrespectivedimensionsbydefiningthresholdsoflevelshuman(in)security.

2. HumanSecurity:TheOriginalApproach,ConceptualChallenges,andPolitical

Consequences

Contemporary thinkingabouthuman securityhasbeen strongly informedbytheHumanDevelopmentReportof1994,arguingtotaketheprotectionoftheindividual as the starting point for political thinking and practice (seeMacFarlane/Kong2006;alsoDebiel/Franke2008).TheUNDPReportintroducedseven socalled dimensions of human security: economic, food, health,

2 Seehttp://www.humansecurityindex.org/?cat=3,10/09/2010.SeealsoHasting2009.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

9/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

7

environmental,personal,communityandpoliticalsecurity.Withthenotionsofglobalization and interdependence becoming more and more clarifiedthroughout the 1990s, the interpretation practice of theUN SecurityCouncilalsoincreasinglychangedwithregardtotheevaluationofthreatsorbreachesto

andofinternationalpeace/security(seedeWet2004:Chap.4).Insum,complexpolitical challenges of development and security, exemplified by suchillustrativecasesasSomaliaorEastTimor,weremoreandmoreperceivedasinterrelated.

The idea of human security is precisely based on this perception ofinterrelatedness:In the finalanalysis,human security isachildwhodidnotdie,adiseasethatdidnotspread,ajobthatwasnotcut,anethnictensionthatdidnotexplodeinviolence,adissidentwhowasnotsilenced.HumanSecurityisnotaconcernwithweapons it isaconcernwithhuman lifeanddignity(UNDP1994:22).Importantly,thenotionalsoimpliesanewperspective:whilsttraditional thinkingabout securitywas firstand foremostconcernedwith the

protectionof thenation state, theconceptofhuman security is laidoutmorebroadlyandargues that the referenceobject shouldbe the individual (UNDP1994:2223).3

Thisdescription already illustrateshowmuch theoriginal idea ofhumansecurityanditsveryoftencriticizedambiguousconceptualizationisrelatedtothediscoursesrevolvingaroundthesocalledsecuritydevelopmentnexus(seee.g. Stern/jendal 2010; Duffield 2010;Hettne 2010; Chandler 2008a, 2008b,2007;Anand/Gasper2007;Martin/Owen2010).DarylCopeland (2009:91), forexample, argues that development mustbeboth made a top priority andunderstood inrelationtosecurity.Hearguesthatunderdevelopment isoneof

the

primary

causes

of

insecurity

and

moreover,

that

addressing

insecurity

effectivelyandeschewing themilitarizationof internationalpolicy in favorofequitable, sustainable,humancentereddevelopmentwill requirea largescalerevisionofprioritiesandasignificantreallocationofresources(Copeland2009:93).

However, as critical scholars have convincingly argued, notions ofbothsecurityand developmentcanalsobeseenasdiscursiveconstructionsthatproduce the reality they seem to reflect,and thus serve certainpurposesandinterests (Stern/jendal 2010: 7). Stern andjendal (2010: 7) emphasize inreference to Chandler (2007): Surely, the power of definition overdevelopmentandsecurityalsoimpliespowertodefinenotonlytherelevant

fieldof interest,butalso thematerial contentofpractices, thedistributionofresources,andsubsequentpolicyresponses.

3 Itisimportanttonotethathumansecurityshouldnotbeequatedwithhumandevelopment.InlinewiththeUNDPReport,wearguethathumandevelopmentremainsabroaderconceptthatis defined as a process ofwidening the range of peoples choices.Human security, on thecontrary,meansthatpeopleareabletosafelyandfreelyexercisethesechoices(UNDP1994:23).

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

10/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

8

In contrast to thesemore skeptical remarks,Martin andOwen (2010), indrawing lessons from theUN and EU experience, see a chance of a secondgeneration of human security emerging if the problem of weakconceptualization, currently especially present in the UNs traditional

understanding of human security, is addressed. That said, the recentlypublishedHumanSecurityReportTheShrinkingCostsofWarneverthelessunderlinesthattheideaisstillaspressingandrelevanttoday.Interestingly,theReportanalyses three interrelateddevelopments thathavebeendrivingdownconflictdeathsformorethanadecade(thatis:thechangingnatureofwarfare,globalhealthpolicyreducingdeathsinpeacetimeandincreasedhumanitarianassistance) (see Human Security Report 2009: 7). This surely illustrates thecomplexinterrelatednessofvariousformsofthreatstohumanbeings.

In sum, human security as such has become an integral part of any(academic) security discourse and in the field of security studies or globalpolitics(seee.g.Collins2007;Baylis/Smith/Owens2008;Booth2005;Ferdowsi

2009).Moreover,when it comes to policy utility and policy relevance, somemight argue that the firstgenerationofhuman security (representedby theUN and Canada) appears tobe in retreat,but one can also argue that asecondgenerationisemerging(Martin/Owen2010:212).However,thesuccessof any human security concept depends on addressing the conceptualchallenges.Otherwiseitmight,infact,stillserveasapoliticalleitmotif,butwillbetrappedinthesaydogapastheambiguityoftheconceptwillproduceonlypoorpossibilitiestoinstitutionalizetheideaasarealpolicyparadigm.

2.1 ConceptualChallengesAlthough the UNDP Report was widely acknowledged for bringing intoperspective an innovative thinking on security, itswideranging implicationsand its conceptual base was criticized especially in academic fora. In thefollowing,we shallpoint to the central aspectsdiscussed in themore recentdebates.4BydrawingonTadjabkhsh/Chenoy(2007:57ff.)webrieflysummarizethecoreaspects.

Firstly, the ideaofhumansecurity iscriticized for itsconceptualweaknessorthelackofaclearbroadlyaccepteddefinition.TheseaspectsmightevenhaveamountedtosymptomsoffailureasonecanobserveagradualimplosionoftheHumanSecurityNetworkandCanadasretreatfromtheforeignpolicyagenda

it

pioneered

(see

Martin/Owen

2010:

211f.;

for

contrasting

position

see

Werthes/

Bosold2006;Bger2008).Infact,onecanstatethattheambiguityoftheoriginalconcept canbe linked to problems of human security to establish itself as a

4 For an overview on the critique and countercritique please refer to the journal SecurityDialogue,whichbrought together21wellknownacademicswho expressed theiropinionsonthe conceptual challenges (e.g. Axworthy 2004; Hampson 2004; Hubert 2004; Uvin 2004;Newman 2004;Alkire 2004; Liotta 2004; Evans 2004; Suhrke 2004;Mack 2004;Krause 2004;MacFarlane 2004;Buzan 2004; Paris 2004;Owen 2004) or to the elaborate illustration of thedebate(s)byTadjbakhshandChenoy(2007:39ff).

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

11/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

9

general principle of public policy and to poor institutionalization of humansecurityasabroadlyacceptedpolicyparadigm.

Secondly, various authors have argued that the idea of human securitymightfallvictimtotheproblemofoversecuritization(seee.g.Paris2004,2001).

As Paris (2004: 371) pointed out: Human security seems to encompasseverything from substanceabuse togenocide.Thisdefinitionalexpansivenessservesthepoliticalpurposeofenticingthebroadestpossiblecoalitionofactorsand interests touniteunder thehumansecuritybanner,but itsimultaneouslycomplicates matters for academic researchers, particularly those who areinterestedincausalhypotheses.

Thirdly, the political implications of a human security agenda have alsobeen criticized on the grounds that they challenge the traditional role of thesovereignstateasthesoleproviderofsecurityaswellastheverysovereigntyofthestateintheinternationalcontext(Tadjabkhsh/Chenoy2007:63).

Lastly, themeasurementofhumansecurityhasbeenandstill isastronglydebated aspect. As is wellknown, critiques argue that the complexity andsubjectivity of the idea of human security makes it difficult to actuallyoperationalizeit.

In sum,muchcriticismcenterson theambiguityor the lackofconceptualclearnessoftheconcept.Thechallengeofanagreedonhopefullyclearenoughdefinitionhasresultedinheatedacademicdebates,pittingthosewhoproposenarrowing the concept against those who want to preserve its holism andinclusiveness(Paris2004:371).Havingsaidthis,itiseasytounderstandwhyscholars and policy makers have viewed human security either as (a) an

attractive

idea

which

lacks

analytical

rigor;

or

(b)

have

tried

to

limit

it

to

a

narrowlyconceiveddefinition;or(c)havearguedthatitisanessentialtoolforunderstanding challenges to peoples wellbeing and dignity (Tadjbakhsh/Chenoy2007:40).Moreover, it iseasytocomprehendwhyamongacademics,thedebateis,first,betweentheproponentsanddetractorsofhumansecurity,andsecond,betweenanarrowasopposedtoabroadconceptualtheorizationofhumansecurity(Tadjbakhsh/Chenoy 2007:40).

2.2 DifferentSchoolsofHumanSecurityandTheirPoliticalImpact

Despite

the

analytical

critique,

the

idea

of

human

security

gained

acceptance

by

politiciansandcivilsocietyalikeandunfoldeditsimpactinthepoliticalrealm.Someauthors suchasBger (2008)orWerthesandBosold (2006)evenarguethatthelackofdefinitionalclarityconstitutesoneofthefactorshelpingtheideatoevolveasaboundaryobjectorpolitical leitmotifand thereby togainpoliticalimpact.

Startinginthesecondhalfofthe1990s,theideaofhumansecuritybegantogainpoliticalimpact.AmongthefirstcountriestoofficiallyadopttheapproachwereCanadaandJapan(inmoredetailseeBosold/Werthes2005;Atanassova

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

12/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

10

Cornelis2006;MacRae/Hubert2001;for theUNseeMacFarlane/Khong 2006).5Especially under the auspices of the then Foreign Affairs Minister LloydAxworthyCanada initiated and/ or supported various efforts guidedby theideaofhumansecurity.TheOttawaProcesstobanantipersonallandminesand

theOptionalProtocolontheInvolvementofChildreninArmedConflictareprobablythe most wellknown success stories. Additionally, in March 1999, the

GovernmentofJapanand theUnitedNationsSecretariat launched theUnitedNationsTrustFundforHumanSecurity(UNTFHS).TheUNTFHS,opentoUNagencies, iscurrentlymanagedbytheHumanSecurityUnit(HSU).Besidethemanagement of the UNTFHS the overall objective of the HSU, which wasestablished inMay2004at theUnitedNationsSecretariat in theOfficeof theCoordinationofHumanitarianAffairs (OCHA), is toplacehuman security inthemainstream ofUN activitiesby playing a pivotal role in translating theconceptofhumansecurity intoconcreteactivitiesandhighlighting theaddedvalue of the human security approach (see http://ochaonline.un.org/

humansecurity).Clearlyrelatedtoabroadperspectiveonhumansecurity,themajority of fundingwasdirected towardsdevelopmental concerns includingkey thematic areas such as health, education, agriculture and small scaleinfrastructuredevelopment.6

Commonlyatleasttwounderstandingsaredistinguishedincurrentpoliticalandacademicdiscourseswhichshareasubstantialcore(seealsoFigure1).Thenarrow school is associated with Canada and to a certain degree with theHumanSecurityNetwork (seese.g.FuentesJulio/Brauch2009).Basically, thisnarrowschoolarguesthatthethreatofpoliticalviolencetopeople,bythestateoranyotherorganizedpoliticalentity,istheappropriatefocusfortheconceptofhumansecurity(inmoredetailseeKerr2007;seealsoBosold/Werthes2005).

This perspective ismainly linked to the idea offreedomfromfear.The broadschoolarguesthathumansecuritymeansmorethanaconcernwiththethreatofviolence.Human security isnot onlyfreedomfromfear but alsofreedomfromwant. This broad perspective is generally associated with Japan, theCommission onHuman Security (CHS 2003) and the UnitedNations TrustFundforHumanSecurity.

More recently, it can be argued that a third perspective or a secondgeneration of human security (Martin/Owen 2010), is evolving whichencompassesthenarrowandthebroadschoolthatonemightcalltheEuropeanschool.Ontheonehand,thisperspective ismorestronglyrelatedtothethird

dimension

ofliberty,

rights

and

rule

of

law

while

it

is

not

strictly

limited

or

primarilyfocussedonthisdimensionontheother.TheBarcelonaReportoftheStudyGrouponEuropesSecurityCapabilities(2004),theMadridReportoftheHumanSecurityStudyGroup(2007),andCounciloftheEuropeanUnion(2003,

5 For a compendium of human securityrelated initiatives and activitiesby members of theFriendsofHumanSecurityandUnitedNationsagencies,fundsandprogramsseeUNGA2008.

6 >>http://ochaonline.un.org/TrustFund/TheUnitedNationsTrustFundforHumanSecurity/tabid/2108/language/enUS/Default.aspx

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

13/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

11

2008) advance this perspective (also see Glasius/Kaldor 2005; 2007;Martin/Owen2010;Sira/Grns2010).

Figure1:HumanSecurityastheNexusbetweenSafety,Rights,andEquity

(Original:

Shahrbanou

Tadjbakhsh/

Anuradha

M.

Chenoy

2007:

52)

Especially,the2008reportisof interestas itmakesmoreexplicitreferencestohuman security.Moreover, the reportdraws extensively, and inmoredetailthaninanypreviousofficialdocumentsoftheCounciloftheEuropeanUnion,onhumansecurityideas.Furthermore,asMartinandOwen(2010)observetheEuropean Parliament and especially the European Commission have eithersupported the shift to human security or explicitlypromotehuman security.Noteworthy, the Commissions definition of human security located itdifferently from that of theUN, combining physical protection andmaterialsecurity,andsitting it firmlywithinacrisismanagementaswellasaconflictresolutionpolicyframe(Martin/Owen2010:219).AsMartinandOwen(2010:

219) furthersubstantiate:While theCommissioncommitted itself to tacklingthe root causes of conflict and vulnerability, the emphasis was less onunderdevelopment per se and more on the integration of a developmentperspectiveintotheEUsforeignpolicytoolkit.Theideaofhumansecuritynotonly served as a tool to mobilize the EUs foreign policy to tackleunderdevelopment and insecurity,but also as ameansbywhich to enforcecooperationbetweenrivalEUpolicystreams.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

14/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

12

2.3 FindingAnswers:AddressingtheDevelopmentSecurityNexus

While agreeing that human development is a muchbroader concept than

human security and that not all human rights issues are linked to securityconcernsas such, it is stillapparent thathuman securityproponents stronglyemphasize adevelopmentsecuritynexus and ahuman rightssecuritynexus.Aspointedoutbefore,humansecuritycommonlyservesaspoliticalobjective(Martin/Owen 2010), political leitmotif (Werthes/Bosold 2006), or boundaryobject (Bger 2008). In essence,what is important tonote is that it couldbeused,first,tocombineshort and longtermpolicyresponses;second,toblurdistinctionsbetween foreign and security policy, andbetween development,humanitarian and crisis management agendas; and third, to integratecommitments to agendas such as gender equality and human rights(Martin/Owen2010:219).However,despitebeingusefulinthissense,thereare

twopossibilitiesinredressingtheconceptualambiguityforpracticalpurposes:first, the above mentioned nexi have to be conceptualized more clearlyregarding their causal links and a second step forward is to propose andadvance a thresholdbased conceptualization ofhuman security (Owen 2004;Martin/Owen 2010;Werthes 2008). That is, rather than securitizing an evergrowinglistofthreatsassuch,allofthesemustprincipallybeconsideredatalltimesassecurityissues.Butanyissueinanylocationhastopassathresholdsothatitcanbecomeasecuritythreat.Onlythosethatbecomesevereenoughtowarrantthesecuritylabelwouldbetreatedassuch(Martin/Owen2010:221).

Thisconceptualizationlimitstheinclusionofthreatsbytheirseverityratherthan their cause.Finally, toenhance thepolitical impactofa thresholdbasedconceptualization of human security, substantiation of specific thresholds isnecessary.Oneway todo this is thecreationofaHuman (In)Security Indexreflecting these underlying conceptual ideas in relation to human securitydimensions.Only theworst threat situations in any country,whatever theircause, areprioritizedwith the labelofhuman (in)security.Allothers remainwithin their constituent disciplines and institutional structures, such asdevelopment,environmentalregulation,orthelegalprotectionofhumanrights(seealsoMartin/Owen2010:221).

Today,manyarguethatthe modernstateora modernunderstandingofsovereignty involves responsibilities and fiduciary duties (see also: Jones/

Pacual/Stedman 2009; ICISS 2001; Bellamy 2009; Evans 2008). Theseresponsibilities and fiduciaryduties literally encompass thewhole agenda ofthe human rights, human security, and human development discourse. Butwhilewelfare and issues of sustainability and a huge part of internationallycodified human rights still onlybelong to the sphere of fiduciary duties,fundamentalhuman rights andbasicneeds aremore andmore consensuallyregardedasresponsibilitiesofthestateor,toputitdifferently,theaspectsthatarediscussedwith reference to the termhuman security.Though the specificset of the boundaries is contested and in flux, one can argue that theinternationalsocietyaccepts thisareaofhumanvulnerabilityasacommonlysharedresponsibilityandismoreandmorewillingtofindwaystotakeupthis

(shared)responsibility.Basedonaprincipleofsubsidiarityaresponsibility to

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

15/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

13

act is postulated. Current state practice shows that this is a sphere whereinternational interference seems to become more and more legitimate,notwithstanding that international interference has tobe appropriate andwellsuitedtobeacceptedaslegitimate.Thismightexplainwhyamajorityof

debates on political strategies and means circulate on ways to establishbenchmarks and thresholds or clear criteria when and how to interfere orintervene in situationswhere the respective state isnotableorwilling toactappropriately.Themostprominentexampleof thiskind is thedebateon theresponsibilitytoprotect(R2P)whichisconcernedwithmilitaryinterventionincasesofmassatrocities.

ThesenexuschallengescanbedescribedwhenworkingonideasoriginallypresentedbyPaulineKerr.Thoughmorelimitedandratherrelatedonlytothedevelopmentsecuritynexus,theseideascanalsobeusedtoexplainthehumanrightssecuritynexus.7Firstly,onecanstatethatproponentsofhumansecuritygrantthemselvestheanalyticalfreedomtostudyalmostany security issueas

an potential threat that is as a dependent or independent variablebecauseinsecurity canbeboth a cause and a consequence of violence (Tadjbakhsh/Chenoy2007:59).Onewaytosubsequentlydevelopaconceptualframeworkisto focuson thenexusbetween thenarrowschools focusonviolenceand thebroadschoolsfocusonhumandevelopment(Kerr2007:95ff).Onemayargueby focusing on political violence that human insecurity is the dependentvariable. Moreover, it becomes apparent that the many causes of humaninsecurityincludeproblemsofunderdevelopment andthatthesecanthereforebe perceived as the independent variables. This leads us to a way ofconceptualizingboth the developmentsecuritynexus and the human rightssecuritynexus.

Our understanding of how to conceptualize four kinds of human(in)securitysituations(levels)areillustratedinfigure2.Thresholdsofthiskindarenecessary (seeabove)as theyhelptopointoutwhenaction isneeded, i.e.whenthereisaresponsibilityto(re)act.Atthelevelofhumansecuritythereareno systematic and sustainable threats to life/survival, though theremightbesecurity issues as such (see above). The level of relative human security ischaracterizedby a situation where some factors and contexts threaten life/survival,but individualsandgroupsgenerallyhaveawaytocopewith thesethreatsorhavethenecessaryhelpattheirdisposal.Inotherwords,peoplearesensitive to (specific) threatsbutnotvulnerable8as theyhaveoptions tocope

with

these

kinds

of

threats,

even

though

these

options

may

produce

(significant)costseithertotheindividualortothecommunity/stateassuch.

7 Additional insights, thoughbased on a different line of argument and perspective, canbegainedbyreadingRoberts(2008).

8 TheideaofsensitivityandvulnerabilityislooselybasedonthethinkingofKeohaneandNye(1977).

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

16/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

14

Sphereof

FiduciaryDuty

Sphere ofthe

Responsibilityto

Prevent

Sphereofthe

Responsibilityto

React

Sphereofthe

Responsibilityto

Rebuild/Prevent

Sphereof

FiduciaryDuty

SaschaWerthes2007

Idealized ProgressionofHumanSecurityPolicy

War,Chaos,Complex

humanitarianemergencies

Thresholdofa

humanitarian

crisis

Thresholdof

vulnerability

Thresholdof

sensitivity

Levelof

Human

(In)Securit

Figure2:LevelsofHuman(In)Security

Level1 Level of human security: There is no systematic and sustainable threat tolife/survival.

Level2 Levelofrelativehumansecurity:Somefactorsandcontextsthreatenlife/survival,

but individuals and groups usually have strategies, means, behavioral options, oraid/helpattheirdisposaltocopewiththesethreats.

Level3 Levelofrelativehumaninsecurity:Somefactorsandcontextsthreatenlife/survivaland individuals and groups have only limited or inadequate strategies, means,behavioraloptions,oraid/helpattheirdisposaltocopewiththesethreats.

Level4 Level ofhuman insecurity:Some factorsand contexts threaten life/survivalandindividuals and groups have no adequate strategies, means,behavioral options, oraid/helpattheirdisposaltocopewiththesethreats.

At the level of relative human insecurity there are factors and contexts that

threatenlife/survival,butaspeoplehave(atthatspecificmoment)onlylimitedor inadequatestrategies,means,behavioraloptions,oraidat theirdisposal tocopewiththesethreatstheyarevulnerabletothesethreats.Finally,atthelevelofhumaninsecurityindividualsorgroupsdonotdisposeatallofanyadequatestrategies,means,behavioraloption,oraid.Thesituationofvulnerabilityissogravethatitresemblesasituationofhumanitariancrisis.

Inthefollowing,weshalllinkthelevelsofhuman(in)securitytonumberstoillustratetherelevanceand inpointoffacttopreparethegroundforanindexthat identifies the actually vulnerabilities of people. This is carried outbyreferring to thedimensionsof theUNDPReport1994and themain threats in

each

region.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

17/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

15

Firstly,typesofthreatsconcerningeconomicsecurityarepersistentpovertyand unemployment. In 2007, the total number of unemployment was 180million,for2008it isestimatedtoaccountfor188million(ILO2009:24).Evenmore so, the 2009 global financial crisis and the slowdown in the world

economic growth including a recession for some of themajor industrializedcountrieshave severely impacted on the labormarket andjobopportunities.Today,morethan620millionpersonsliveinextremepovertyoflessthanUS$1.25adayandthenumberofworkingpoorisstillprojectedtoriseinthefuture(ILO2009:3),resultinginincreasedglobalpoverty.Themostinsecurejobsaretobe found in the informal sector, a feature of a majority of developingcountrieswheresomesortofsocialnetorinsuranceismissingforlargepartsofthepersonsworkingintheinformalsector(Canagaraja/Sethuraman2001).

As regards potential threats that canbe identified in the environmentaldimension, climate change can lead to increased shortage ofwater and thedegradation of land. This significantly can produce the effect of increasing

energycostsandtheheighteneddemandfornaturalresources.Moreover,itisfrequentlypointed out that conflicts can lead to thedeterioration of health causingmortality,morbidityormalnutrition.Muchresearchhasfocusedonthelink of poverty and conflicts and in this context, the connection of poverty,restricted access to education,health and conflictbecomes evident (Pedersen2009).Onehasonly to thinkof the landbasedconflicts inSomalia tobecomeawareoftheinterlinkageshere(Dehrez2009).Thenumberofdeathscausedbynatural catastrophes accounted for 235,000 in 2008,mainly effectedby twomajor incidents, the abovementioned Cyclone Nargis and the SichuanearthquakeinChina(AnnualDisasterStatisticalReview2008:1).Thenumbersfor the 2006 and 2007 are similarly alarming despite the fact that nomajor

events suchasNargis and theSichuanearthquake tookplace: in 200623,000personswerekilledbynaturaldisasterscausingmorethanUS$34.5billion ineconomic damages (AnnualDisaster Statistical Review 2006). The year 2007witnessed16,847deaths;however,more than211millionotherswereaffectedbyoverall414naturaldisasterscausinganeconomicdamageofUS$74.9billion(AnnualDisasterStatisticalReview2007).

With a view to the food dimensions, alarming numbersmake clear thenecessity for appropriate policy (re)actions: According to the Food andAgriculturalOrganizationoftheUnitedNations(FAO),68percentofthetotalpopulationinEritreawereundernourishedin2005,63percentinBurundiand

46

per

cent

in

Ethiopia

(FAO

Food

Security

Statistics

2008).

This

figures

point

to

the severity of undernourishment especially for developing countries.According to theFAO,nearlyonebillionpeoplesufferfrommalnutritionandhungertoday.Thisproblem isclosely linked toadditionalaspectssuchas theeconomic and social status a person enjoys. It should alsobe stressed thatsufferingfromhungerandbeingundernourishedleadstoanalarmingnumberofdeaths:25,000persons(adultsandchildren)dieeverydayfromhungerandrelatedcauses (FAO2008:SOFIReport).About11millionchildrenunder fivedieindevelopingcountrieseachyear,malnutritionandhungerrelateddiseasescause 60 percent of the deaths of children (UNICEF 2007: The State of theWorldsChildren).

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

18/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

16

Equally alarming numbers canbe identified in the health dimensions ofhumansecurity.TheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)listsmorethanfifteeninfectiousdiseasesaffectinghumanbeingsworldwide, themost importantofthembeingmalariaand tuberculosis. In2006, therewere247millioncasesof

malaria,leadingtonearlyonemilliondeaths,mostlyamongchildreninAfrica.The number of persons infectedwith the TB virus is also disastrous: today,approximately9millionhumanbeingsare infectedwith theTBvirus thathascausedabout1.5milliondeaths in2006 (http.www.who.org).The2008ReportontheGlobalAidsEpidemicestimatesthenumberofadultsandchildrenlivingwithHIV 33,000,000, the vastmajority of them living in SubSaharanAfrica(22,000,000)(UNAIDS2008:214).ThefurtherspreadofHIV/AIDSwillcontinuetoposeaworldwidesecurityrisk.

Having identified the necessity of conceptual thresholds of human(in)security the next step is to point out away how to operationalize thesethresholds inreferencetothehuman(in)securitydimensions identifiedbythe

original UNDPconcept. That is to assess human (in)security. As we havearguedabove,conceptualizingahuman(in)securityindexisrelevanttoassesscertain security issues as actual threats (and in doing so, we argue for theconceptualizationofcertain thresholds).However,andequally important, theoverview on actualnumbersofdeaths related to thedifferentdimensions ofhuman (in)security underscores the necessity to develop a measurementinstrument.

3. AddressingtheChallenge:AHuman(In)Security

Index

We shall address this challengeby presenting aHuman (In)Security Index(HISI)based on the original human security dimensions presentedby theUNDPidentifiedintheHumanDevelopmentReportof1994.Thecrucialtaskistohelptodevelopbenchmarkstomonitortheimpactsofagivenpolicyandtohelptoformulatecoursesandagendasofaction(seealsoUNUCRIS2009).Inthismanner,notonlyoneofthefundamentalcriticismsismet,evenmoresothepracticalrelevanceofhumansecuritycanbeenhanced.Findinganswerstotheproblemofhumaninsecurityrequiresaninstrumenttoassesstheactualthreatstohumanbeings.Besides,humansecurity isalsounderstoodasanattemptto

shed light on the root causes of insecurity (Werthes/Debiel 2006: 10). To findappropriate policy responses, it is important to measure the actual threatsrelated to insecurity.This alsohelps to identifypriorities forpolicy agendas,since the idea ofhuman securityhasbeen increasingly included indecisionmaking,policydesignandprogrammaticimplementation.

Previouscontributionswhichhavefocusedoncreatinganindexmeasuringhuman security are primarily restricted to a narrow approach to humansecurity. To date, the debate on the possibilities of measuring human(in)security has predominantly been shaped by the miniAtlas of HumanSecurity (formerly the Human Security Report), published by the HumanSecurity Report Project and the World Bank. TheminiAtlas predominatelyprovidesdata for insecurityrelated towarsandarmedconflicts (miniAtlasof

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

19/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

17

HumanSecurity2008),butdoesnot take intoaccount threatscausedbynonviolent factors such as undernourishment, infectious diseases and naturaldisasters.

Oneofthefirstattemptstooperationalizeadefinitionhowhumansecurity

maybemeasured is the concept of generalized povertyby Gary King andChristopherJ.L.Murray.Generalizedpovertyexistswhenadefinedthresholdforacertaindimensionisreached.Theauthorsofthisconceptargueinfavorofa universal decision for indicators of measuring human security in aquantitativemannerworldwide (King/Murray2001:11ff).Anoverallstateofgeneralized poverty for a population in all relevant dimensions can thenbeidentified through a quantitative approach using survival analysismethods(King/Murray 2001: 609f). Therefore the concept of generalized poverty issubstantially related to an economic dimension of security. In contrast, ourattemptwillalsotakeintoaccountotherdimensions(whicharenotcloselyandsolelylinkedtoeconomicwellbeinglike,forexample,politicalsecurity).

Perhaps themost forwardpushing attempt to create an Index ofHumanSecuritysofarhasbeenmadebyDavidA.Hastings.Thisindexmainlyaimsatextending the Human Development Index with indicators that attempt tocharacterizeinclusiveincome,knowledge,andhealthcareasactuallydeliveredtopeople (Hastings2009:10).ThisEnhancedHumanDevelopment Index isdevelopedtocreateaprototypeHumanSecurityIndex(Hastings2009:11ff)based on ideas of theUNDP 1994 human security definition. The EnhancedHDIshallthenprogressivelybeadvancedtoaHumanSecurityIndex.

We agreewithHastingswhen drawing attention to the fact that initialingredientsofaHumanSecurityIndexnowexistwhicharerelatedtothefact

thatinternationallycomparabledatasetsforavastfieldoftopicsinthefieldofeconomic and development are available today and the possibility for theconstructionofindicesforavastfieldhasbeenimproved(Hastings2009:18f).HastingsconstructshisSocialFabricorHumanSecurityIndex(HSI)alongthedimensions of: protection of (and benefiting from) diversity, peace,environmental protection, freedom from corruption and informationempowerment and additionally draws the attention to the imperfectness ofindicatorsonanaggregatedcountry levelasacriticalremark.9This isalsoanissuewe take intoaccountwhenconstructingourHuman (In)Security Index,butwillnotdiscussindetail.IncontrasttoHastingsapproachofproducingaSocialFabricorHumanSecurityIndexweattempttostrictlyoperationalizethe

core ideas of the respective UNDPs human security dimensions. There aresome dimensions that are operationalized in a similarway inboth indices.However, our index focuses on aworldwide relation of human (in)security.Hastingsmainlydraws the focusonAsia and thePacificasa regional index(Hastings2009:8).10

9 Foramoredetaileddescriptionpleasesee:http://www.humansecurityindex.org/?page_id=147.

10 AregionalindexhasbeenrecentlypublishedbytheUniversityofthePhilippinesThirdWorldStudiesCenterthatexaminesthehumansecuritysituationinthePhilippines,seeAtenziaetal.2009.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

20/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

18

Anotherapproachhasbeen thevery fruitful (early)operationalizationandcomputationofanIndexofHumanInsecurity (IHI)developedbytheGECHS(GlobalEnvironmental ChangeandHumanSecurity)project in2000.Humaninsecurityisdividedintothedimensionsofenvironment,economy,societyand

institutions.Countries are firstly differentiated along categories of insecurityintotencategoriesandarethenaggregatedtorankeachcountryonanoveralllevelof insecurity.Longitudinaldata from1970up to1995 isused togainanoverallvalueforinsecurity.11

WemainlyfollowtheideaoftheGECHSprojectasregardsthestructureoftheaggregationof thedimensionsofhuman insecurity.However,wemodifythedimensionsandchoiceofindicators.IncontrasttoGECHSwewillskipdatainterpolation formissing values due to the fact thatwewill only use crosssectionaldatafor2008andnotatimeseriesoveralongerperiod.Thisaimsatavoidingahighnumberofmissingvaluesespecially inperiodsprior to2000and inadditionatgettingatimepoint imageofhuman insecurityratherthan

anaverageforalongertimeperiod.TheindexresemblessomeelementsoftheGECHSconstructionbut focusesonadefinedpoint in time (namely theyear2008)anddiffers in thechoiceofoperationalizeddimensions. Inotherwords,sincewechooseasimilaraggregationtechniqueinsomeareasofourindex,itisinawaycomparable to theearlyattemptofGECHS.However,we takeonasignificantlydifferentperspectiveofoperationalizationofhuman(in)securityasaconcept.ThisarguesforareasonableextensionoftheattemptofGECHS.

In line with our understanding of human insecurity as vulnerability ofpeople,ouroperationalization for theHuman (In)Security Index isevenmorecloselybasedontheoriginalthinkingoftheUNDPReportasweinterpretit.

However,

there

is

one

exception:

The

dimensions

of

Personal

and

Community

Securityare combined toonedimensiondue topracticalandmethodologicalreasons: Personal security focuses on the basic threats caused by physicalviolence,be it from states, groups or individual persons,whilst communitysecurityaimsatprotectingpeople from their lossof traditionalpracticesandmembershipincertaingroups,beitafamily,acommunity,anorganizationoraracial or ethnic group from which people derive cultural identity. Tests inpreparation of the index have shown that for now (due to the availablestatisticaldata) the linkage (andcorrelation)between these twodimensions isespeciallyhigh:given the fact thatviolationofphysical integrityalso impactsoncommunitytrustand levelsofbehaviorincommunities.Ahighnumberof

violent

acts,

regardless

whether

carried

out

by

state

or

non

state

actors,

have

a

negativeimpactonsocialcohesionwhichcanbemoreeffectivelymaintainedinfunctioningcommunities.

TheHuman(In)SecurityIndexconcentratesonthevulnerabilityofpeopleinatwofoldway:firstly,assessingtheactualthreatineachdimensionallowsforadifferentiatedunderstandingof therespective insecuritydimensionassuch.That is, it allows for differentiation: whilst, for example, the dimension of

11 Detailedaggregatingprocedureandchoiceofindicatorscanbefoundontheprojecthomepage:http://www.gechs.org/aviso/06/.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

21/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

19

environmental securitymay show low values, the threat to political securitymaybemuch higher for the same country.This could lead todifferentiatedagendaswhenhaving tosetprioritiesandwill therebyhelp todirectpriorityandattentionto(morerelevant)areasofconcern,andpreventfuturedamages

in a more precise and efficient way. The Human (In)Security Index willcontribute to a better alignment of the assessment of vulnerability andcorrespondingagendasetting.Tothateffect,strategiccoursesofactionmaybechosen,dependingonthevalueofeachdimension.Secondly,theoverallvaluefor each country sheds light on the actual human (in)security situation in agiven country; countriesmaybe compared toeachotherand those countrieswhosecitizensarethreatenedmostseverelycanclearlybeidentified.Thismayhelp to gather additional momentum to ask for governmental and nongovernmentalpolicyresponsesandtherespectiveresourcesneeded.

3.1 PreliminaryRemarksontheHuman(In)SecurityDimensionsInthissection,weshallexplicatetheseveraldimensionsandpointtoindicativethreats that canbe identified in eachdimension.Additionally, the indicatorschosenforeachdimensionareshortlyintroducedandsubstantiated.

TheHumanDevelopmentReportstatesthatEconomicSecurityrequiresanassuredbasic income,usually fromproductiveand remunerativework,or inthe last resort from apublicly financed safetynet (UNDP 1994: 24). In otherwords,economicsecuritymeansbeingabletoprovideforaminimumstandardoflivingor,ifthisisnotthecase,beingsecuredbysomekindofsocialsecurityprovidedbythestateorprivateactors.Accordingly,unemploymentaswellasunderemploymentisindicativeissue/threatstoeconomicsecurity.Bothcanbe

compensated (tovaryingextent)byanexistingsocial safetynet.Thismaybeprovidedbyeitherthestateorprivateactors.12Whatismore,theactualaccessto public services can account for another factor that endangers economicsecurity. It is therefore crucial tomeasure the equal access individuals enjoyregardlessoftheirsocialbackground,theirreligion,ethnicityandgenderandtoestimatetowhatextentinstitutionsaresufficientlyabletocompensateforgrosssocialdifferences(BertelsmannTransformationIndex2008).

Againstthisbackground,economicsecurityisoperationalizedby:

a) Gross Domestic Product per Capita at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)(Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook

Database2008)andthe

b) BertelsmannTransformationIndexCombinationoftwoIndicators:SocialSafetyNetsandEqualOpportunity(Source:BertelsmannFoundationBTI2008)

12 Theauthorsarewellawareofthefactthat socialsafetynetsdonotexistineverycountryandthattheymaysometimesbesubstitutedtoavaryingextentbythefamilyorthecommunity.However,dataavailabilitydoesnotofferthepossibilitytomeasurethiskindofsocialsafety.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

22/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

20

The first indicator was chosen since it illustrates the overall economicperformance of a given country allowing for international comparison. Thisindicatorwas chosen instead of unemployment rates since definitions of anunemployedpersonstronglyvaryacrosscountries,whichmakes international

comparisonveryproblematic.The indicatorsofSocialSafetyNets andEqualOpportunity are part of the Status Index regarding the state of themarketeconomyinacountryandarepartofthesubcriterionofthewelfarestate.Thepresenceofsocialsafetynetsdepictsthegivenpossibilitytocompensatefortheloss of income, health care and prevention of poverty. Measuring equalopportunity shows towhat extent a country provides equal access to publicservicesforitscitizens.

Food Security implies that allpeople at all timeshavebothphysical andeconomicaccess tobasic food.This requires thatpeoplehave readyaccess tofoodthattheyhaveanentitlementtofood,bygrowingitforthemselves,bybuying itorby takingadvantageofapublic fooddistributionsystem (UNDP

1994:27).Theproblemhere isnotthemereavailabilityoffood,buttheactualaccess individuals enjoy tobasic food. This might eitherbe constrictedbyunequal distribution (physical access) or the lack of purchasing power(economicaccess).What ismore,malnutritionmaybecausedbyavarietyoffactors such as social structures, armed conflicts, lack of education orenvironmentalcatastrophessuchastheCycloneNargisthatstruckMyanmarinMay2008.Thecyclonestronglyaffected thecountry thatwasalreadymarkedby a dire humanitarian situation with growing impoverishment anddeterioratingsocialservicestructures.Humanbeingsareevenmorevulnerabletoeconomiccrisisornaturalshockshere(InternationalCrisisGroup2008).

Accordingly,

food

security

is

measured

by

the

a) NumberofChildrenUnderFiveUnderweighted forAge (Source:WorldHealthOrganizationWHOSTATIS2006)andbythe

b) Percentage of Population that is Undernourished (Source: Food andAgriculturalOrganizationFAOSTAT20032005).

Measuringchildmalnutritionisinternationallyrecognizedasawaytoestimatethenutritionalstatusandhealthinpopulationsingeneral.Whatismore,childmalnutrition is linked to several other factors such aspoverty, low levels ofeducation and limited access to health care. Children who suffer frommalnutritionasaresultofpoordietsaremorevulnerabletoillnessesanddeath,

malnutrition also affects their cognitive development and their health statuslater in life.A failure tomeet theseneedswillhavepermanentconsequencesthatmay include stunting, reduced cognition and increased susceptibility toinfectiousdiseases(GlobalHungerIndex2008:27).Assuch,thisindicatoralsoshowsthethreatstopotentialfuturedevelopmentofyounggenerations, oftenoneofthemorevulnerablegroupswithinthesocietiesasalreadyindicatedbythe remarks on youth unemployment at the beginning of this chapter.Additionally,thepercentageofthepopulationthatisundernourishedprovidestheoverallpictureof thevulnerabilityofhumanbeingswith regards to foodsecurity.

FoodSecurityiscloselyrelatedtothedimensionofHealthSecuritywhichisdirected towards theprotection frommajorcausesofdeath, includingmainly

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

23/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

21

infectiousandparasiticdiseasesespeciallyindevelopingcountries.Mostofthedeaths causedby infectiousdiseases are linked tomalnutrition andpollutedwater.Forindustrializedcountries,themajorcausesofdeatharediseasesofthecirculatorysystem,oftenconnectedtodietandlifestyle(UNDP1994:27).What

ismore, pollutedwater constitutes one of themajor causes for diarrhea, awaterrelateddisease causingup to 4 per cent of victimsworldwide (GlobalWaterSupplyandSanitationAssessmentReport2000).Furthermore, thespreadof HIV/AIDS poses another major risk to health security. Additionally,epidemicsmayalsoaffectthefunctioningofsocieties,sinceillhealthmaybeadirect cause for poverty since it reduces the possibility of productive andremunerativework and is thus directly related to an increase in householdincome(Pederson2008:27).

It is evident that the problem of infectious diseases can no longer beregardedasamedicalproblemalonebuthastobelinkedtosecurityissues,too.The crossborder characterof infectiousdiseasesheightens the importanceof

implementing efficient strategies to encounter continued human loss, anoutstanding concern especially since the infectionwith the abovementioneddiseasescanactuallybeprevented.Againstthisbackground,infectiousdiseasesandtheinfluenceonchildmortalityrates,ascanbeexemplifiedbythedeathscausedbymalaria,arethemostimportantthreatstohealthsecurity.

According to this,ourHuman (In)Security Indexmeasureshealthsecuritybythe

a) NumberofTotalPopulation affectedbyDiseases (Source:WorldHealthOrganizationWHOGlobalHealthAtlas2007)andthe

b)

Child

Mortality

Rate

(Source:

U.S.

Census

Bureau,

International

Database

2008).

The number of total population affected by diseases depicts the casesmentioned above and demonstrates how vulnerable individuals are towardsinfectious diseases. The following diseases are aggregated within the firstindicator: HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and cholera. Additionally,measuringthechildmortalityrateconstitutesoneoftheleadingindicatorsforthelevelofchildhealthandtheoveralldevelopmentinacountry.Similarlytotheindicatormeasuringchildrenunderfivethatareunderweightedthisfactorpointsouttheoverallhealthinapopulation.

As defined by the Human Development Report 1994 EnvironmentalSecurityincludesthreats inflictedbythedegradationoflocalecosystemsandthat of the global system,mainly globalwarming. In developing countries,access to cleanwater is increasinglybecoming a reason for ethnic strife andpolitical tension, whilst for developed countries the pollution of the airconstitutes amajor threat to environmental security (UNDP 1994: 28ff.).Thelinkbetweenenvironmentalissuesandhuman(in)securityisespeciallyclose,asmuchof the environmentalproblems aredirectly affectedbyhuman activityand yet, their security isbound to the access to natural recourses and theirvulnerability to environmental change (Khagram/Clark/Raad 2003). Globalwarmingcausingamultitudeofeffectssuchas increases inglobalaverageairand ocean temperatures, thewidespreadmelting of snow and ice and risingglobalaveragesealevelposesafiercethreattothesecurityofhumanbeingsat

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

24/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

22

global level. Furthermore, natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods,droughtorwildfireposeanothermajor risk to thewellbeingand securityofhumanbeings.

Besidessuchdirecteffectsasthetotalnumberofreportedvictimscausedby

environmental catastrophes, there are also more indirect and longlastingconsequencesfortheenvironment,theagricultureandindustrialproductionsothatthefuturedevelopmentofsocietiesisincreasinglyendangeredwhenhitbynaturaldisasters.Consequently,environmental securitynotonlycauseshumanbutalsoeconomic losses.Achangingenvironmentcanimpactnotonlyonthewellbeinganddignityofhumanbeings,butalsooneconomicproductivityandpolitical stability.Competition aboutwater resources constitutesaprominentcaseinpoint.Asmentionedabove,pollutedwaterisoneofthemainproblemsin developing countries and access to clean water may cause or heightenpoliticalunrest.However,waterpollutionmainlyresultsfrompoorsanitationwhich iswhy the second indicator as statedbelow combines two factors to

depictthiscloserelation.Withregardstoanotheraspect,wateraccessnotonlyisacrucialconditionforthesurvivalandwellbeingofhumanbeings,butalsoneededforagricultureandtheindustry.

Against this background, environmental security is operationalized by thefollowingtwoindicatorswhichisfirstlythe

a) Percentage of Population that is Affected by Disasters (Source: TheInternationalEmergencyDisastersDatabaseEMDA2006)andsecondlythe

b) Mean of Percentage of Population with Access to Clean Water and

Percentage

with

Access

to

Improved

Water

Sanitation

(Source:

Joint

MonitoringProgrammeforWaterandSupplyandSanitationbyUNICEFandWHO2006)

The first indicator shows thepercentageof thepopulation that isaffectedbydisasters,suchasfloodsorearthquakesandiscrucialsinceithelpstopaintthebroader picture that is causedby environmental catastrophes. Crossbordernatural disasters are a particular evident example that security and livingconditionsinonecountrycanaffectthesecurityandlivingconditionsofothercountriesor even inother regions.This is also true forother factors such asinternational terrorism or migration. The second indicator combines twoaspects, access to cleanwater and access to improvedwater sanitation,both

factorsstronglyrelatedtoimprovedenvironmentalconditions.

Asmentionedabove,wechosetocombinethefollowingtwodimensionstoonedimension, that is, Personal SecurityandCommunity Security.PersonalSecurity is defined as security from threats from physical violence. Thesethreatsmaycomefromthestate(physicaltorture),fromotherstates(war),fromother groups of people (ethnic conflicts), from individuals (crime or streetviolence,theymightbedirectedagainstwomen(rapeordomesticviolence)andthreattoselfsuchasdrugsorsuicide(UNDP1994:30).Clearly,thisdimensioncoversawiderangeofthreatstohumanbeingsoriginatingfrommostdifferent

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

25/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

23

sources.Wewillconcentrateonviolenceexecutedby thestate,whichwillbefurtheroutlinedbelow.13

Community Security aims at the protection of people from their loss oftraditional practices and membership in certain groups, be it a family, a

community, an organization or a racial or ethnic group fromwhich peoplederivecultural identity, thatprovide themwith security.A lossof traditionalpracticesmaybe causedbymodernization,but alsoby sectarian and ethnicviolence(UNDP1994:31f.).

Of the persons that are most vulnerable with regards to personal andcommunity security, internally displaced persons (IDPs) are probably thelargestgroupintheworld(Fielden2008:1).Theirsecurityisaffectedinmanyways: They are often denied theirbasic human rights, are endangeredbyphysicalviolence,areunprotectedbytheirnationalgovernmentandthusmaysuffer from malnutrition, missing access to clean water, health care and

education.

Woman

and

children

are

especially

vulnerable

in

those

conditions

andarethreatenedbysexualandgenderbasedviolence.IDPsmostlylackanyeconomic opportunities so that they are hardly able to secure a minimumstandardoflivingbythemselves(Fielden2008).Insum,IDPsarefacedwithavariety of lifethreatening concerns. Despite the multiple reasons for theirdisplacementand thevarietyof subgroupsof IDPs, theircommonground isthelinktobothcommunityandpersonalsecurity.Beingturnedintoarefugeeorinternallydisplacedpersonmakesindividualsmorevulnerabletotheabovementioned threats.What ismore, formerly functioning communities that arewartornandaffectedbypolitical tensionsmightno longer serveas securingbasis for individualswho derive their security from theirmembership to a

certain

ethnic,

religious

or

racial

group.

Quite

the

contrary

might

be

the

case

giventhefactthatbeingamemberofacertaingrouporfamilymightactuallybe the cause for insecurity which is then again clearly linked to personalinsecurity.Refugeeandmigrationflowsalsoindicatepossiblefurtherinsecuritysincethesocietalinfrastructuremightbedamagedandthuscommunitiesmoveaway from traditional forms of solidarity and societal trust is continuouslydecreased.Causingdamagestothesocietalinfrastructuremaythenalsoinflictuponotherdimensionsofhumansecuritysuchaseconomicorhealthsecuritywhen access to productive and remunerative work or to health care isaggravated.

Thecombineddimensionofpersonalandcommunityisoperationalizedbythe

followingtwoindicatorswhicharethe

a) TotalNumber of people assistedby the UNHCR (Source:UN RefugeeAgency2006)andthe

b) PoliticalTerrorScale(Source:PoliticalTerrorScaleProject2007).

13 Pleasenote:Dataoncrimeandstreetviolence,rapeanddomesticviolence is lackingandnotreliable,especiallyfordevelopingcountries.Forthisreason,thesethreatswereexcludedfromouroperationalizationandareindirectlymeasuredbyoursetofindicators.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

26/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

24

ThePoliticalTerror Scalemeasures the levels ofpolitical violenceusing twodifferentsources,theyearlyCountryReportsofAmnestyInternationalandtheU.S.StateDepartmentCountryReportsonHumanRightsPractices.ThePTSrathermeasurestheviolationsofphysicalintegrityrightsthangeneralpolitical

repression,forwhichreasonthisindicatorischosentooperationalizepersonalsecurity.The PTSmeasure state violence (admittedly, it isnot always clearwhether thestate isdirectlyresponsible forviolence),however, the indicatordoesnotincludeviolenceexecutedby individuals,e.g.crime,orgenderbasedviolencesuchasdomesticviolenceagainstwomenorfemalegenitalmutilation(Wood/Gibney 2008: 3ff.). According to the latest reports by AmnestyInternational, we still witness gross violation of human rights despite theprogressmadeinhumanrightsprotectionoverthepastyears.

Finally, the dimension of Political Security is addressed. Following theHumanDevelopmentReport1994,politicalsecurity focuseson theprotectionofbasic human rights,which is, as theReport emphasizes, one of themost

importantaspectsofhumansecurity.Violationsofhumanrightsmayespeciallyoriginateduringtimesofpoliticalunrest,butalsofrompoliticalrepressionbythestateorsystematictorture(UNDP1994:22f.).

One of the major concerns up to date is securing people from staterepression.2,390peopleareestimatedtohavebeenexecutedworldwide;China,SaudiArabiaandUSAaccounted forthehighestnumberofexecutions.Then,freedomofthepressisoneofthemostessentialrightsandhighlyindicativeforthisdimensionofhumansecurity.For thepast threeyears (2006 to2008), thePressFreedomIndexlistsNorthKorea,TurkmenistanandEritreaastheworstviolatorsofpress freedom.Countries such as Iraq,PakistanandAfghanistan

which

are

involved

in

armed

conflict

and

failing

to

solve

dire

domestic

problemsarealsorankedasblackzonesforthepress(PressFreedomIndex2008). TheHuman (In)Security Indexwill use the following two indicators,whichare

a) Index of Five Indicators14 concerning Personal Security (Source:HumanRightsDataProjectCIRI2006)

b) PressFreedomIndex(Source:ReporterswithoutBorders2006)

Itisimportanttonotethatboth,PTSandCIRI,usethesamedatatocodetheirindicators, that is, statesponsored violations of human rights termed asphysical integrity rights.However, theCIRIdivides the category ofphysical

integrity violence into several subcategories, which are: disappearances,killing,tortureandimprisonment(whicharefouroutoffiveindicatorsusedforthe operationalization carried out here). Secondly, the PTS ranks thegovernment abuses, whilst the CIRI analyses the frequency and type ofviolation so that these two indicators paint a different picture, though they

14 The indicators are:Disappearance,ExtrajudicialKilling,Political Imprisonment,Torture andAssassination. All Indicators are codedon a scale ranging from 0 (frequentlypracticed) to 2(havenotoccurred).Forafurtherdescriptionseehttp://ciri.binghamton.edu/documentation/ciri_variables_short_descriptions.pdf.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

27/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

25

clearly correlatewith each other (on detail see the remarks in chapter 4.2)(Wood/Gibney 2008). The Press Freedom Index is composed from aquestionnaire that comprises 52 questions on press freedom that theorganization Reporters without Borders distributes among its partner

organizationsonanannualbasis.Havinglaidoutourconceptualbackgroundforthechoiceofindicators,we

will now point out the methodological background for developing andconstructingtheHuman(In)SecurityIndex(HISI).

3.2 Methodology:ComputationoftheHuman(In)SecurityIndexThe aim of the Human (In)Security Index as presented in this paper is tooperationalizethecoredimensionsofhumansecurity.Thishastwo importantimplications: Firstly, the indicators that were chosen to operationalize eachdimensionmeasurehumaninsecurity.Secondly,wewillpolarizeourindicators

inanegativeway,meaningthehigherthevalue,thehigherthethreattohumansecurity.Bydeveloping thiskindofHuman (In)Security Indexweareable toidentify the dimensions which present the most severe threats at a givenmomentoftime.Thismayputadditionalimpetusonthenecessitytorespondtospecificthreatsandmayhelptopreventafurtherdeteriorationofthehuman(in)security situationas such.Weargue thataHuman (In)Security Indexwillcontributetoananalyticalrefinementofthenotionofhumansecurityandwillalso allow for improved strategic actions since efficient policies towards thedifferentfieldsofactivityareneededtorespondtotherootcausesofinsecurity.In short, a Human (In)Security Index will help to improve vulnerabilityassessmentandprioritysetting.

TheHuman (In)Security Index includes209countriesandregions (suchasGazaandtheWestBank).ThesixdimensionsasdefinedbytheUNDPReport(personal and community security are combined to one dimension) areoperationalizedby two indicatorseachandareaggregated tocountryspecificvalues.Figure3illustratesthemanifestindicatorsandthelatentconstruct(thatis: human insecurity) they measure. The Human (In)Security Index is arelationalindextothemaximumandminimumvalueofeveryindicator(andina second step to every dimension). Although outliers are computed out,extreme cases (in relation to themean)maybias the data. This applies inparticulartotheenvironmental dimension,wheresingularcasessuchasaone

time

natural

disaster

may

occur.

Given

such

a

situation,

a

high

percentage

of

thepopulationmightbeaffected.Thescoreforallothercountriesiscomputedintorelationtothat.Thiscertainlydoesnot implythat,forexample,thegreenenvironmental dimension should be interpreted as a complete absence ofaffectedpeople.However, the threateningpotential ishardlyathandhere inrelationtotheextremecases.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

28/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

26

Figure3:MatrixofIndicatorsandDimensionsoftheHuman(In)SecurityIndex(HISI)

There are threepossible and adequateways to compute the indicatorvalues

andtoaggregatethemtotheseveraldimensions(OECD2008:83ff):

Zstandardizationofvalues(withthemeanasareferencepoint) Definingintervalsonourown(oroncomputingquartiles) RescalingthevaluesthroughcomputationIt is important to keep in mind that these methods can onlybe used forvariablesmeasuredonametriclevel.Forvariablesonanordinallevel(liketheBertelsmannTransformation Index forSocialNetsor thecombinationofCIRIindicators)aspecificcomputationisusedtorescalethevaluesbetween0and100 (this range is thebasis for all indicators tobe aggregated to dimension

value).Thecomputingproceduresaccountforthefollowingmetricvariables:

GrossDomesticProduct perCapitabased on (Purchasing Power Parity PPP)

ChildrenUnderFiveUnderweightedforAge PercentageofPopulationthatisUndernourished TotalPopulationAffectedbyDiseases ChildMortalityRate PercentageofPopulationthatisAffectedbyDisasters Mean of Percentage of Population with Access to Clean Water andPercentagewithAccesstoImprovedWaterSanitation

TotalNumberofpeopleassistedbytheUNHCRTheindicatorsarerescaledbasedonthefollowingformula:

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

29/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

27

Allcountriesarerankedintheirrelationtotheextremecases(withthehighestand lowest score on the indicator) at a range of 0 to 100. In thisway, thecountriesexperiencingextremeproblemswithregardstohumaninsecurityareespeciallypointedout.Toavoidanartificialskewnessregardingtooutlierswe

excluded the general calculationby adequately identifying them from eachindicatorsdistribution.15

Afterwardsthemeanforeverycountryineverydimensioniscalculatedby:

Thedimensionvalues for every country are summedupanddividedby thenumber of valid rated dimensions to gain a country value for the overallHuman (In)Security Indexwhich is the overallmean of allvaliddimensions

(some

countries

do

not

have

valid

values

on

every

dimension

due

to

the

fact

of

lackingdata).Theformulaforthisprocedureis:

The dimensions and the overall index then varybetween 0 (lowest level ofhuman insecurity)and100(highest levelofhuman insecurity).It is importanttonote thatall indicatorshave thesameweightingfor thecomputationofthedimensions.Oneexceptionoccurs:whenacountryhasamissingvalueinone

of the two indicators, itsdimensionvalue is identicalwith thevalid indicatorvalue.Inastatisticalmanner,the indicatoristhenoverestimatedinrelationtoalldimensionsindicatorswithmorethanonevalidvalue.However,thisdoesnothinder the analytical interpretation as thisonly counts for thedimensionvalue,theoverallIndexofHuman(In)Securityisthereforeacombinationofthedimensionsvaluewithconstantweightsofeverydimension.

After computing thevalues,wedivide theHuman (In)Security Index intoquartileslabelledinthefollowingcategoriesbyscores(seeTable1).Inlinewiththe computationprocedure, the index isanadditiveandnot amultiplicativeone.

15 A country canbe regarded as an outlierwhen its value differsmore than three standarddeviationsfromtheindicatorsmean.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

30/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

28

Table1:AssessingtheLevelofHuman(In)Security

LevelHuman(In)Security

LevelScore Definition

1Level

ofHumanSecurity 025Thereisnosystematicandsustainablethreattolife/

survival

2LevelofRelativeHumanSecurity

2650

Somefactorsandcontextsthreatenlife/survival,butindividualsandgroupsusuallyhavestrategies,means,behaviouraloptions,oraid/helpattheirdisposaltocope

withthesethreats.

3LevelofRelativeHumanInsecurity

5175

Somefactorsandcontextsthreatenlife/survivalandindividualsandgroupshaveonlylimitedorinadequatestrategies,means,behaviouraloptions,oraid/helpat

theirdisposaltocopewiththesethreats.

4 LevelofHumanInsecurity 76100Somefactorsandcontextsthreatenlife/survivaland

individualsandgroupshavenoadequatestrategies,means,behaviouraloptions,oraid/helpattheirdisposal

tocopewiththesethreats.

3.3 FindingsInthefollowingsection,thefindingsineachdimensionarepresentedaschartsillustrating the frequencies of countries falling in the respective categories ofhuman (in)security at a regional macro level.16 Additionally, for somedimensionsaworldmap thatcorrespondswith the typology laidout in table

oneisincluded.17Itshouldbenoted,thatalthoughtwocountriesmayfallintooneinterval,theirvaluesmaydiffertosomeextentwhenbotharelocatedatthedifferent end of the interval. This is the case, for example, for Belgium andBelaruswhichboth fall into the levelofhumansecurity (seeAnnex2),butofcourse differ from each other especially with respect to political security.Additionally,itisimportanttokeepinmindthateventhecategoryofrelativehuman securitymight imply aproblematic level foranadequate life, that is,routinesofdailylifemightbeconstrainedalsothere.

3.3.1 HumanEconomic(In)SecurityAnoverallsecure levelofeconomicsecurity (GDPpercapitaandexistenceofSocialNets) ismainly athand inNorthAmerica,WesternEurope and somepartsofAsiaandOceania.InAfrica,onlyasmallnumberofcountriesreachthehighest category, for example,Gabon,Namibia, Botswana and SouthAfrica.

16 TheregionsareidentifiedaccordingtoUNSTATSidentificationnumbers.Fordetailsseehttp://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm.

17 Foracompleteoverviewonallworldmaps,pleaseseewww.humansecurity.de.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

31/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

29

Theoverallhighest threat toeconomic securityoccurs inAfrica,especially intheDemocraticRepublicofCongo,GuineaBissau,SomaliaandLiberia.NearlyallpartsofAfricaareaffectedbyarelativelyhighlevelofeconomicinsecurityand15countriesareonthehighestlevelofhumaninsecurity(outofoverall19

countriesinthiscategory).Incomefordailylifeisverylowandvastlimitationsof an adequate life occur. If the case of unemployment is at hand, a highnumberofAfricancountrieslackaminimumnetofsocialsafetytocompensatefor the problem of economic insecurity that is causedby notbeing able tosecure aminimum standard of living. Since theBertelsmannTransformationIndex (oneof the indicators for thisdimension)alsomeasuresaconstraint inequal(economic)opportunitiesbesidesalackofsocialsafetynets,ahighlevelof insecurity impliesrestrictions inbothaspects.Thisapplies tosomepartsofSouthAsia.Moreover,NorthKorea,Afghanistan,MyanmarandNepalfacethesame economical problems, but even India, Pakistan, Indonesia and othercountries in East Asia with their overall high population numbers fail in

providing adequate economic opportunities. In the Americas, Bolivia andParaguayandsomepartsofCentralAmericaface thesameeconomicsecurityproblems.

Overall,AfricaandSouthtoSouthEastAsiaaremostaffectedbythreatstoeconomicsafetyandsecurity.EspeciallyinAfricanearlyallgeographicregionsface alarming problems. Economic insecurity is one of the major problemsworldwide.Theimportancetochallengethisthroughpovertyreductionisstilloneofthemajortaskstoday,evenmoresosinceeconomicsecurityisstronglyrelatedtohealthandfoodsecurity.

Table2:RegionalDistributionofHumanEconomic(In)Security

UNMacro

Region

EconomicDimensionNumberofCountries

fallinginoneofthehuman(in)securitylevels

TotalNumberof

Countries

Level1 Level2 Level3 Level4

Africa 3 9 25 15 52

Oceania 2 5 2 0 9

Americas 8 20 7 0 35

Asia 9 15 18 4 46

Europe 27 9 4 0 40

Total 49 58 56 19 182

3.3.2 HumanFood(In)SecurityFood insecurity, measured by the percentage of population that isundernourishedandthenumberofchildrenunderfiveunderweightedforage

isasevereproblemmainly inAfricaandSouthAsia.EspeciallyinSubSahara

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

32/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

30

Africa,foodsecurityisamajorproblemforhugepartsofthepopulation.SomecountrieslikeEthiopia,Eritrea,theDemocraticRepublicofCongo,AngolaandMadagascarfacealarmingscoresinthisdimension.

Inotherpartsoftheworld,onlyAfghanistanfalls intothiscategory(Level

of Human Insecurity). But even some countries in SouthEast Asia (Laos,Cambodia,Bangladesh,NepalandIndia)andYemenfaceproblemsconcerningtheadequatesupplyoffoodfortheirpopulation.Besidesthesecountries,foodinsecurityingeneraldoesnotconstituteacentralproblemforCentralAsiaandtheMiddleEastregion. In theAmericas,Haitikeepson facingproblemswithfundamental food supply for its population. The same applies (with somerestrictions) toBolivia,Nicaragua andGuatemala. Food insecurity inEuropecanberegardedasabsent.Here,theproblemofmissingdataforthisdimensionoccurs,however, it canbe assumed thatSpain,Poland,PortugalandAustria(withmissingdata)willnotbe ranked as highly alarming concerning foodinsecurity.18

Table3:RegionalDistributionofHumanFood(In)Security

UN

Macro

Region

FoodDimensionNumberofCountriesfallinginoneofthe

human(in)securitylevelsTotalNumber

ofCountries

Level1 Level2 Level3 Level4

Africa 12 19 14 7 52

Oceania 7 1 0 0 8

Americas 28 5 2 0 35

Asia 27 10 7 2 46

Europe 39 1 0 0 40

Total 113 36 23 9 181

18 Data providedby FAOSTAT cover the years 20032005 (latest available year used), sinceadequateandreliabledataisproblematicor/andnotavailableforthefollowingyears.

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

33/68

AssessingHumanInsecurityWorldwide

31

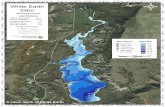

Figure4:WorldMapHumanFood(In)Security

-

8/4/2019 Report 102

34/68

Werthes/Heaven/Vollnhals

32

3.3.3 HumanHealth(In)SecurityHealth insecurity is measured by the occurrence of infectious diseases(HIV/AIDS,malaria,choleraandtuberculosis)andthechildmortalityrate.All

partsofSubSaharanAfricafacetheseproblems.Infectiousdiseasesoccurinallofthesecountries,malaria,HIV/AIDSandtuberculosisarealarmingproblemsforahighnumberofAfricancountriesandtheirpopulation.Itcanbeassumedthat already for today the spread ofHIV/AIDS influences the economicallyworkingpartofAfricancountries.ApartfromAfrica,onlyAfghanistan(duetotheworldwide highest number of childmortality) and PapuaNew Guineareach such a disastrous status. InAsia, Pakistan,Mongolia, Bangladesh andLaoshealthinsecurityalsoisaproblem.Havingthisstated,healthinsecurityisin general nomajor problem in the Americas (only Haiti is affected here),Oceania (except PapuaNewGuinea, the Solomon Islands and TimorLeste),AsiaandEurope.