Rehabilitation of burn patients: An underestimated socio-economic burden

-

Upload

hans-oliver -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Rehabilitation of burn patients: An underestimated socio-economic burden

Rehabilitation of burn patients: An underestimatedsocio-economic burden

Ursula Mirastschijski a,*, Jan-Thorben Sander b, Birgit Weyand b, Hans-Oliver Rennekampff b

aDepartment of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Klinikum Bremen-Mitte and School of Engineering and Science,

Jacobs-University, Bremen, and Hannover Medical School, Hannover, GermanybDepartment of Plastic, Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Burn Center Lower-Saxony, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Accepted 7 June 2012

Keywords:

Health care costs

Burns

Sequelae

Rehabilitation

a b s t r a c t

Purpose: Patients with burns utilise intensive medical care and rehabilitation. Deep dermal

burns lead to scar contractures. Virtually no published data exists on costs for treatment of

acute burns in comparison to burn sequelae. Our purpose was to collect financial data on

burn therapy to estimate the socio-economic burden of thermal injuries.

Methods: German-DRG for in-patient treatment of burns was collected from our burn center.

DRG-related T95.- coding served as a search tool for burn associated sequelae. To include

rehabilitation costs, data from the largest health care insurance and a workmen compen-

sation fund were acquired.

Findings: Acute burn treatment comprised 92% of costs for intensive care with approxi-

mately 4.600 EUR per percent total burned surface area (TBSA). Expenses for non-intensive

care patients were significantly lower than for burn sequelae. Rehabilitation expenses were

4.4-fold higher than costs for acute burns including 59% for manual therapy and 37% for

auxiliary material.

Conclusions: TBSA multiplied by factor 4600 could serve for cost calculation of severely

burned patients. Approximately 0.3 billion EUR in total or 270.000 EUR per patient/year were

spent on burn sequelae. Early admission to specialized burn centers is advocated with state-

of-the-art treatment to minimize burn sequelae and health care expenses.

# 2012 Elsevier Ltd and ISBI. All rights reserved.

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/burns

1. Introduction

Globally, 11 million people presented with burns in 2004 [1]. In

European countries, 4–22% of these patients were hospitalized

[2]. In Germany, 20,000 burns are registered per year with 4000

patients receiving general hospital care and 1200 being

admitted to specialized intensive care units of burn centers

[3]. In comparison with the U.S. [1] or other European countries

* Corresponding author at: Department of Plastic, Reconstructive Surge28177 Bremen, Germany. Tel.: +49 4214975787.

E-mail address: [email protected] (U. Mirast

Abbreviations: AOK, Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse; BG, Berufsgenonational Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Probarea.0305-4179/$36.00 # 2012 Elsevier Ltd and ISBI. All rights reserved.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2012.06.009

[2], Germany has only few severely burned patients with 1.5

per 100,000 inhabitants [4]. Men encounter thermal injuries

2 [1] to 3 [2] times more often compared to women. Children

and elderly people are high risk groups for burns with

incidences between 15% [4] and 58% [5] or 20% [6], respectively.

Fifty to 80% of all childhood burns occur during the first 5 years

after birth [2].

In 2006, 16.2 million people were admitted to German

hospitals with only 0.2% (25,723) being treated for burns [7]

ry and Aesthetic Surgery, Klinikum Bremen-Mitte, St.-Jurgen-Str. 1,

schijski).

ssenschaft; G-DRG, German-Diagnose Related Groups; ICD, Inter-lems; MHH, Hannover Medical School; TBSA, total burned surface

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8 263

comprising 1200 patients with utilisation of intensive care [4].

Thirty-eight German burn centers provide currently highly

specialized treatment according to current burn therapy

standards. After general stabilization and accomplished

wound healing, patients are either transferred to general

wards or to rehabilitation centers [8]. Besides posttraumatic

wound and skin care, a multitude of rehabilitative measures

are employed in order to reintegrate a burn victim into social

and professional life, e.g. physiotherapy, psychotherapy,

manual therapy, massages, splints, prostheses and epitheses

[9,10]. In case of occupational disability rehabilitation pro-

grams are initiated to qualify patients for a more suitable job;

in case of invalidity, annuity insurances and workmen

compensation funds cover for disability pension.

In Norway, annual expenses of 10.5 million EUR arise per

year for in-hospital care of burn patients [11]. In the US,

between 3000 and 5000 USD were spent per day for acute

burns in 1996 [12]. A Spanish burn center conducted a

prospective study with mean costs of USD 95,551 per acute

burn patient and year in 2001 [13]. Taking into account that

burn patients require long-term follow-up and intensive

aftercare, it is amazing that literally no data exist for these

expenses.

The aim of this study was to compare costs between

treatment of acute burns and burn sequelae and to differentiate

between in-patient and out-patient costs. Data from 3 different

sources were compared to state expenses for burn aftercare.

2. Methods

Three different data sources were used to assess treatment

costs.

(1) German Diagnosis Related Groups (G-DRG) accounting for

in-patient treatment after acute burn and for secondary

surgery for burn sequelae at the Department of Plastic,

Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Hannover Medical

School, from 2006 to 2009;

(2) Acute and follow-up treatment costs of burn victims being

insured by the compulsory health care insurance, Allge-

meine Ortskrankenkasse Niedersachsen (AOK) from 2008

to 2010; and

(3) Treatment costs of the 16 most costly patients of the

Workmen compensation fund BG-ETEM (Berufsgenos-

senschaft Energie, Textil, Elektro- und Medienerzeugnisse)

from 2005 to 2010.

The Ethical Committee of Hannover Medical School

approved the study prior to start (No. 578/2009). All data from

each source were acquired anonymously without the possi-

bility to track or identify any patient.

1. German-DRG of burn patients from Hannover Medical

School

The patient database of the Department of Plastic, Hand

and Reconstructive Surgery was screened in order to analyze

treatment costs for in-patients with burn sequelae. DRG is an

economic-medical classification system grouping main and

side diagnoses and different treatments per case for reim-

bursement by insurance companies. G-DRG of the Major

Diagnostic Category (MDC) 09, i.e. skin diseases, and MDC 22,

i.e. burns, were used. Patients were selected according to their

diagnoses, coded by the International Statistical Classification

of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10, version

2006). Main selection criterion follow-up treatment was T95.-

coding for ‘‘sequelae after burn, chemical burn or frostbite’’

according to chapter XIX, ICD-10.

The total burned body surface area (TBSA) was correlated

with treatment costs for acute burn. The DRG reimbursement

sum was provided for acute and follow-up treatment by our

controlling department. Data were analyzed within a time

period of 36 months (2006–2008).

2. Data from the public health care insurance

About 90% of patients are covered by public compulsory

insurances in Germany, the largest being ‘‘Allgemeine

Ortskrankenkasse’’ (AOK) with 24 million members. Each

federal country of Germany holds subdivisions of health

care insurance and AOK Niedersachsen (Lower-Saxony)

kindly provided data of their members. AOK Lower-Saxony

covers 2.4 million people. Databases were screened anony-

mously for patients with burn related ICD-10, i.e. T20.- to

T31.- between January 2008 and June 2010, e.g. 30 months.

For aftercare treatment, ICD-10 codes were used for burn

sequelae T95.- and for scar formation L90.5, L91.0 in

combination with T20.- codes.

Treatment costs were subsumed into 4 categories: (a) in-

patient acute burn care; (b) patient readmissions for treat-

ment of burn sequelae; (c) adjuvant therapies, e.g. physio-

therapy, massages, and manual therapy; and (d) auxiliary

materials, e.g. pressure garments, prostheses, epitheses,

splints, glasses, and medications.

3. Cost analysis of the Workmen compensation fund BG-ETEM

BG-ETEM insures workers in the industrial branches of

energy, textiles, electrical devices and media products

comprising 3.6 Mio employees of 250,000 companies

(http://www.bgetem.de/aktuell/ap_jahresbericht.html). BG-

ETEM agreed to provide anonymous data of their 16 most

costly patients after burn covering a time period between

January 2005 and June 2010. Expenses were subdivided

into costs for medical treatment including hospitalization,

adjuvant therapy, and auxiliary materials.

2.1. Statistics

A binominal distribution with p = 0.5 was assumed for

individual events and p-values were derived for the observed

configurations, i.e. the likelihood that a particular observed

event count is greater or equal to its value when originating

from a binominal distribution. For comparison of the means of

patient cohorts with maximal costs, the Kruskal–Wallis-Test

was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered

statistically significant. The normal distribution belongs to

the maximum domain of attraction of the Gumbel distribution

(single-peaked) which, together with the given robustness of

102

103

104

105

Follow-upNon-ICUICU

Co

sts

(E

UR

)

******

**

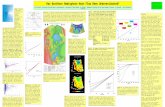

Fig. 1 – Comparison of acute and follow-up in-patient costs

assessed by G-DRG. Acute burn patient costs were

subdivided into costs for treatment on intensive burn care

unit (ICU, median 17,636 EUR, n = 113) and for treatment

on the ordinary plastic surgery ward (non-ICU, median

2335 EUR, n = 110). Both cohorts were compared with costs

for follow-up treatment (median 2726 EUR, n = 109) using

Kruskal–Wallis-Test. Boxes represent 25th to 75th

percentile range (interquartile range), whiskers 5th to 95th

percentile range and horizontal lines within the boxes

indicate the median values. p-Values are given for

statistical significant outcomes. **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8264

the Kruskal–Wallis-test, makes the statistical comparison

presented herein sufficient [14].

3. Results

Costs for in-patient treatment of acute burns and burn

sequelae in a German burn center were assessed by G-DRG

coded reimbursement system. In-patient data for acute burn

care was subdivided into costs for treatment on the burn

intensive care unit (ICU) or on the ordinary in-patient ward of

the department. Data of our hospital (MHH) was compared

with expenses of the public health care insurance (AOK) and

workmen compensation fund (BG). Because burn follow-up

care comprises adjuvant therapies, e.g. rehabilitation, and

auxiliary material, data of health care insurance and a

workmen compensation fund were used to calculate out-

patient expenses.

3.1. Costs for in-patient care

3.1.1. Burn center expenses, MHHTreatment for acute burns comprised in-patient stay on the

ordinary ward and/or on the burn ICU including all

surgical procedures. Adjuvant therapy and auxiliary mate-

rial of these patients during their hospital stay are part of

the G-DRG reimbursement and not paid separately by

insurers.

Ten-times more money was reimbursed for acute burn

treatment compared to burn sequelae. Costs for acute care

amounted to 3.8 Mio EUR (16,857 � 2027 EUR, n = 223; mean

per patient � SEM) in comparison to 371,826 EUR (2946 � 222

EUR, n = 109) for treatment of burn sequelae within 36

months. Notably, most of the costs (92%) were due to

intensive care of severely burned patients (median 17,636

EUR; max 190,015 EUR/min 436 EUR; n = 113; Fig. 1) with

statistical significance compared with either non-ICU acute

(median 2335 EUR; max 7067 EUR/min 436 EUR; n = 110) or

follow-up patients (median 2726 EUR; max 14,227 EUR/min

616 EUR; n = 109; p < 0.0001). Interestingly, costs for follow-up

treatment of burn sequelae were significantly higher

( p < 0.001) compared to non-ICU patients with acute burns

(Fig. 1).

3.1.2. Public health care insurance, AOKA total sum of 4.8 million EUR (n = 599) was spent by public

health insurers on in-patient care for acute burns within a

time period of 30 months, six-fold more than for hospitaliza-

tion of follow-up patients. Four times more money, e.g. 21.4

million EUR, was spent on treatment of burn sequelae

compared with expenses for the acute accident (Table 1).

Table 1 – Public health care insurance’s (AOK) expenses for ac

Acute burn

In-hospital stay Total In-hosp

Costs (EUR) 4,872,233 (n = 599) 21,354,679 783.895 (

Percentage 100 4

Interestingly, in-patient expenses amounted up to only 4% of

all burn sequelae costs.

3.1.3. Most expensive casesComparing 15 most expensive cases of all data sources yielded

similar costs for acute patients of our department (MHH;

median 85,371 EUR; max 190,015 EUR/min 40,002 EUR) and of

public health care insurance (AOK; median 94,385 EUR; max

303,333 EUR/min 70,597 EUR; Fig. 2). In-patient care costs were

significantly lower assessed by workmen compensation fund

(BG, median 32,764 EUR; max 113,784 EUR/min 9831 EUR)

compared to MHH ( p < 0.001) or AOK ( p < 0.001). No differ-

ences between all groups were found for follow-up in-patient

treatment (MHH: 23,334/26,895/16,974 EUR; AOK: 12,925/

231,418/1889 EUR; BG: 18,630/136,732/12,560 EUR; median/

max/min; n = 5; Fig. 2).

3.1.4. Costs per total burned body surfaceDepending on patient age and burn localization, ICU monitor-

ing and treatment is recommended in patients with more than

15% total burned body surface area (TBSA). In-patient costs for

acute burns of the burn center (MHH; mean 110,443 EUR,

ute and chronic burn treatment.

Burn sequelae

ital stay Adjuvant treatment Auxiliary material

n = 36) 12,548,015 (n = 149) 8,022,769 (n = 79)

59 37

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5x 10

5

MHH AOK BGAcute Cases

Costs

(E

UR

)

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5x 10

5

MHH AOK BGFollow-up Ca ses

**

**

Fig. 2 – Comparison of treatment costs for most costly in-patients treatments of burn center MHH, and expenses of public

health care insurance AOK and workmen compensation fund BG. Patient cohorts were compared with regard to costs for

acute (n = 15) and follow-up (n = 5) treatment using Kruskal–Wallis-Test. Median values were for acute costs 85,371 EUR

(MHH), 94,385 EUR (AOK) and 32,764 EUR (BG) and for follow-up costs 23,334 EUR (MHH), 12,925 EUR (AOK) and 18,639 EUR

(BG). Statistically significant differences were found between acute cases of MMH versus BG or AOK versus BG ( p < 0.001).

No significant differences were noted between follow-up costs. Boxes represent 25th to 75th percentile range (interquartile

range), whiskers 5th to 95th percentile range and horizontal lines within the boxes indicate the median values. p-Values

are given for statistical significant outcomes. **p < 0.001.

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8 265

n = 15) were significantly higher ( p < 0.001) compared to

workmen compensation fund (BG; 46,835 EUR, n = 15, Fig. 3).

In the specific patient cohort of workmen compensation

fund BG, burn was mostly inflicted by electricity and to a lesser

degree to direct fire or scalds. In our cohort, patients presented

with an average TBSA of 27% (Table 2). The average TBSA of

BG’s patients was 9%. To enable comparison of diverging

0

20.000

40.000

60.000

80.000

100.000

120.000

140.000

Acute cAcute cases

Tre

atm

ent costs

(E

UR

)

**

Fig. 3 – In-hospital treatment costs of the most costly patients (

fund, BG for acute and follow-up treatment. Acute costs were sta

burned body surface area (TBSA) at initial hospital stay. Costs i

compensation fund, BG; **p < 0.001.

patient cohorts (burn center MHH and workmen compensa-

tion fund BG), in-patient costs were related to TBSA.

By calculating costs per TBSA, expenses evened out to 3944

EUR/percent TBSA in our patient cohort and to 5204 EUR/

percent TBSA in BG ( p = 0.07, n = 15). Thus, an average of

approximately 4600 EUR per percent TBSA per patient can be

estimated for acute burn care (Fig. 3).

Burn sequelaeases per TBSA

n = 15) of burn center, MHH, and workmen compensation

ted as mean W SEM or divided by mean percentage of total

n EUR; white bars burn center, MHH, black bars workmen

Table 3 – Financial expenses of workmen compensationfund (BG) for patients with burn.

Costs (in EUR) Total Percentage

(1) In-hospital treatment

(a) acute burn 704,530 (n = 16)

Burn sequelae

(b) follow-up treatment 109,420 (n = 10) 33

(c) in-patient rehabilitation 134,601 (n = 5) 41

(2) Adjuvant treatment 55,424 (n = 8) 17

(3) Auxiliary material 27,956 (n = 13) 9

Table 2 – Comparison of in-patient costs between burncenter and workmen compensation fund normalized topercentage total burned body surface area.

In-patient costs in EUR MHH BG

Acute costs** (n = 15) 110,443 � 13,053 46,835 � 9364

Acute costs per % TBSA 3944 � 466

(mean TBSA 27%)

5204 � 1040

(mean TBSA 9%)

Follow-up costs (n = 5) 17,215 � 1873 24,402 � 12,876

Mean � SEM.** p < 0.001.

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8266

3.2. Costs for out-patient care

Out-patient care comprised adjuvant treatment with physio-

therapy and manual therapy, and auxiliary material, e.g.

pressure garments, casts, prostheses, silicone sheets, and

other prescriptions. Public health care insurance stated a total

of 20,570,784 EUR with major expenses for adjuvant treatment

(12,548,015 EUR, e.g. 59%) and auxiliary material (8022,769 EUR,

e.g. 37%, Table 1). Ninety-six percent of all follow-up costs

were non-hospital expenses and only 4% for readmissions.

Workmen compensation fund data differed to public

health care insurer’s information. In-patient costs constituted

74% (244,021 EUR, n = 10) of all follow-up expenses with 33% for

readmissions (109,420 EUR, n = 10) and 41% for in-hospital

rehabilitation therapy (134,601 EUR, n = 5). Adjuvant treat-

ments comprised 17% (55,424 EUR, n = 8) and auxiliary

material 9% (27,956 EUR, n = 13) of follow-up costs (Table 3).

4. Discussion

Financial expenses for acute and follow-up burn patient

treatment were assessed from data of a German burn center,

the largest public health care insurance and a workmen

compensation fund. When equated to percentage TBSA, acute

burn costs were comparable between different data sources.

The majority of expenses for follow-up treatment, e.g. 96%,

were due to patients’ rehabilitation and scar prevention

therapy, and only 4% for in-hospital treatment.

The total sum of around 21.4 Mio EUR was spent by the

largest regional health care insurance, AOK Lower Saxony,

from 2008 till 2010 for burn sequelae. Thus, costs amounted to

8.6 Mio EUR per year. This is 4.4 times more than for acute burn

treatment. AOK Germany covers 36% of all patients insured by

public health care providers who insure over 90% of all

Germans. Data extrapolation leads to an estimate of 270

million EUR for surviving patients with burn sequelae after

intensive care treatment per year. Considering the fact that

burns and electrical injuries comprise only 2.4% of all

accidents, and that German global health care costs amounted

to 245 billion EUR in 2006, this underlines the socio-economic

impact of long-term treatment with regard to the relatively

small patient cohort of burn victims.

As expected, treatment on the burn intensive care unit

comprised the major part of acute burn costs with 92%. The

median reimbursement was 17,636 EUR in our patient cohort

corresponding well to previous reports of burned children

with USD 17,220 for acute in-patient stay in 2002 [15]. Taking

inflation and currency exchange rates into account, this sum

corresponds to DRG charges for acute injury in-hospital stay

in this study [15]. Anecdotal case reports [16] and studies with

smaller patient numbers [17] state higher costs for acute burn

patient care. When most expensive cases were compared in

our cohort, significant differences were only found with

regard to data of workmen compensation fund BG. In contrast

to the burn center and public health care insurance with

heterogeneous patient groups, BG covers workers of the

industrial branches energy, technique, electricity and media

with higher proportional incidence of burns inflicted due to

the electrical current. This might explain statistically signifi-

cant differences to G-DRG reimbursement. However, when

costs were calculated in relation to percentage of TBSA,

differences equaled with an average amount of 4600 EUR per

percent TBSA. Multiplying TBSA with a factor of 4600 may

help to estimate socio-economic costs for acute burn care of

severely burned patients according to the burned total body

surface. Inhalation injury, burn thickness or other accompa-

nying trauma can aggravate burn disease and prolong

treatment. Unfortunately, no detailed data on these points

was available which might have contributed to more accurate

cost calculations.

Less than 5% of costs were due to in-hospital treatment, e.g.

readmission for surgery, with major expenses for rehabilita-

tive (59%) or supportive measures (37%). Considering the

intensive physiotherapeutic treatment that can extend over

several years and the need of splinting and compression

garments to prevent post-burn scarring and loss of function,

these numbers do not surprise. Intensive physiotherapy is

essential not only for joint mobility but also for patients’

reintegration into daily life and work. Already in 1995, Fletchall

and Hickerson reported substantial total cost reductions of

40% by converting hospital bound rehabilitation to an out-

patient setting concentrating more than 80% of expenses on

out-patient treatment [9]. However, carefully designed clinical

studies demonstrating the efficacy of pressure therapy are still

needed for optimal duration and tailor-made individual, cost-

effective post-burn treatment [18,19].

The astonishingly small amount for in-hospital treatment

contradicts political accusations of costly in-patient stays.

Polytraumatized patients are a comparable patient cohort

with similar incidence per year [20] and G-DRG reimbursement

for acute care [21]. Comparable to our findings with burn

patients, Hausler et al. noted for Swiss polytraumatized

patients that most of the health care costs were due to

absence from work and rehabilitation with only 5.1% of costs

for hospitalization [22]. Notably, admission of severely burned

patients or patients with inhalation trauma to specialized

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8 267

burn centers is generally recommended for better survival and

functional outcome [23]. Due to inferior outcome results, a

European working party launched guidelines for burn patient

treatment outside from burn centers [24]. Considering the fact

that rehabilitation measures comprise 96% of total costs for

burn sequelae, we emphasize the need for early and highly

specialized patient care at burn centers with continuous early

and intensive adjuvant treatment already during primary

hospital stay.

An explanation for the obvious divergence between

AOK’s total expenses and burn center’s data is that DRG-

derived costs are budgeted per case and account for the

complete in-hospital treatment. The Burn Center Lower-

Saxony is an over-regional burn center with a wide-spread

catchment area of 300 km for severely burned patients.

Therefore, the proportion of admitted patients with minor

thermal injuries to those with severe, life-threatening burns

is shifted to the latter explaining higher costs for acute burn

patients.

Epidemiological data on burn victims in Germany indicates

an average of 27% TBSA [6,25] corresponding to our data and

showing that both minor and major burned patients were

equally admitted to our department. In contrast, BG’s injured

workers presented with lower TBSA, e.g. 9%, possibly due to

the different type of inflicted burn in this professional cohort.

Despite relatively small TBSA, expenses for the initial hospital

stay doubled follow-up costs (Table 3). These expenses may

reflect high co-morbidities of patients after electrotrauma

with limb amputation rates of 45–71% [26].

In contrast to public health care insurance, in-patient costs

for workers constituted 74% of follow-up costs, with 41% for

in-hospital rehabilitation treatment. This discrepancy is

explained by the fact that workmen compensation funds

are highly interested in fast occupational rehabilitation of the

employees into the working process. High in-patient costs

with intensive adjuvant treatment lead to faster recovery and

reduce long-term working disability funding [27]. Notably, 67%

of all follow-up expenses were consumed by rehabilitation

measures.

In conclusion, annual health care costs for burn sequelae

exceed expenses for acute burns with an estimate of 4600 EUR

per percent TBSA for severely burned patients. Main financial

burden constitutes in long-term rehabilitation in contrast to

negligible costs for secondary admissions. Early referral of

acute burn victims to specialized centers is advocated for

state-of-the-art treatment and better long-term outcome.

Thereby, burn sequelae can be minimized with better life

quality, reintegration into the working process and reduction

of socio-economic expenses.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors disclose that there are no financial and personal

relationships with other people or organisations that could

have inappropriately influenced (bias) our work, e.g. in form of

employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria, paid

expert testimony, patent applications/registrations, and

grants or other funding.

There was no financial funding of this study.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Dr. med. P. M. Vogt, chairman of the Department of

Plastic, Reconstructive and Hand Surgery, is acknowledged for

support of this study. B. Rhode, controlling, Department of

Plastic, Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Hannover Medical

School provided G-DRG data and helpful discussions. R. Keye,

BG-ETEM, and Dr. J. Weber, AOK Niedersachsen kindly

provided data of their patient cohorts. U. Zier is acknowledged

for statistical expertise.

Appendix A

Table for currency conversion:

Year EUR USD GBP JPY

2006 1 1.256 0.682 146.015

2007 1 1.370 0.684 161.253

2008 1 1.471 0.796 152.454

2009 1 1.395 0.891 130.337

Average (2006–2009) 1 1.373 0.763 147.515

EUR, Euro; USD, US Dollar; GBP, British Pound; JPY, Japanese

Yen. Averages are stated from each day of corresponding year

(www.ecb.int/stats/exchange/eurofxref/html/index.en.html,

access 05.05.2012).

r e f e r e n c e s

[1] Peck MD. Epidemiology of burns throughout the world.Part I: distribution and risk factors. Burns 2011;37:1087–100.

[2] Brusselaers N, Monstrey S, Vogelaers D, Hoste E, Blot S.Severe burn injury in Europe: a systematic review of theincidence, etiology, morbidity, and mortality. Crit Care2010;14:R188.

[3] Ziegenthaler H, Neumann U, Fritzsche U, Suhnel B.Polytraumatized burn injury victims. Orthopade2005;34:906–16.

[4] German Burn Association DGV. Burn statistics; 2009, http://www.verbrennungsmedizin.de/statistik.php.

[5] D’Souza AL, Nelson NG, McKenzie LB. Pediatric burninjuries treated in US emergency departments between1990 and 2006. Pediatrics 2009;124:1424–30.

[6] de Roche R. Epidemiology. In: Bruck JC, Muller FE, Steen M,editors. Handbuch der Verbrennungstherapie. Landsberg:Ecomed; 2002. p. 27–33.

[7] German Federal Office for Statistics SB. Health-DRGstatistics of in-patients according to operations andprocedures. Bonn: DIMDI; 2009. p. 2–27.

[8] Spires MC, Bowden ML, Ahrns KS, Wahl WL. Impact of aninpatient rehabilitation facility on functional outcome andlength of stay of burn survivors. J Burn Care Rehabil2005;26:532–8.

[9] Fletchall S, Hickerson WL. Quality burn rehabilitation: cost-effective approach. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16:539–42.

[10] Spanholtz TA, Theodorou P, Amini P, Spilker G. Severe burninjuries: acute and long-term treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int2009;106:607–13.

b u r n s 3 9 ( 2 0 1 3 ) 2 6 2 – 2 6 8268

[11] Onarheim H, Jensen SA, Rosenberg BE, Guttormsen AB. Theepidemiology of patients with burn injuries admitted toNorwegian hospitals in 2007. Burns 2009;35:1142–6.

[12] Keswani MH. The 1996 Everett Idris Evans MemorialLecture. The cost of burns and the relevance of prevention.J Burn Care Rehabil 1996;17:485–90.

[13] Sanchez JL, Pereperez SB, Bastida JL, Martinez MM. Cost-utility analysis applied to the treatment of burn patients ina specialized center. Arch Surg 2007;142:50–7. discussion 7.

[14] Embrechts P, Kluppelberg C, Mikosch T. Applications ofmathematics: stochastic modelling and applied probabilitymodelling extremal events. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York:Springer Verlag; 1997. p. 645.

[15] Foglia RP, Moushey R, Meadows L, Seigel J, Smith M.Evolving treatment in a decade of pediatric burn care. JPediatr Surg 2004;39:957–60. discussion-60.

[16] Eldad A, Stern Z, Sover H, Neuman R, Ben Meir P, WexlerMR. The cost of an extensive burn survival. Burns1993;19:235–8.

[17] Dimick AR, Potts LH, Charles Jr ED, Wayne J, Reed IM. Thecost of burn care and implications for the future on qualityof care. J Trauma 1986;26:260–6.

[18] Anzarut A, Olson J, Singh P, Rowe BH, Tredget EE. Theeffectiveness of pressure garment therapy for theprevention of abnormal scarring after burn injury: a meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009;62:77–84.

[19] Bloemen MC, van der Veer WM, Ulrich MM, van Zuijlen PP,Niessen FB, Middelkoop E. Prevention and curativemanagement of hypertrophic scar formation. Burns2009;35:463–75.

[20] Gruppe VIII A. FallpauschalenbezogeneKrankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik): Diagnosen,Prozeduren und Fallpauschalen der vollstationarenPatientinnen und Patienten in Krankenhausern.Destatis. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt;2008. p. 1–68.

[21] Probst C, Schaefer O, Hildebrand F, Krettek C, Mahlke L. Theeconomic challenges of polytrauma care. Unfallchirurgie2009;112:975–80.

[22] Hausler J-MC, Zimmermann H, Tobler B, Arnet B, Husler J.Die volkswirtschaftlichen Kosten vom Polytrauma. Luzern:Print Suva Schweizerische Unfallversicherungsanstalt;2001.

[23] Herndon DN, Spies M. Modern burn care. Semin PediatrSurg 2001;10:28–31.

[24] Alsbjorn B, Gilbert P, Hartmann B, Kazmierski M, MonstreyS, Palao R, et al. Guidelines for the management of partial-thickness burns in a general hospital or communitysetting—recommendations of a European working party.Burns 2007;33:155–60.

[25] Ziegenthaler H. Empfehlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaftfur Verbrennungsmedizin zur RehabilitationBrandverletzter. Bad Klosterlausnitz: Deutsche Gesellschaftfur Verbrennungsmedizin; 2007.

[26] Buttemeyer R. Das Elektrotrauma. In: Bruck JC, Muller FE,Steen M, editors. Handbuch der Verbrennungstherapie.Landsberg: Ecomed; 2002. p. 464–74.

[27] Sheridan RL, Hinson MI, Liang MH, Nackel AF, SchoenfeldDA, Ryan CM, et al. Long-term outcome of childrensurviving massive burns. JAMA 2000;283:69–73.