Reconciling conflicting evidence on the elasticity of ...

Transcript of Reconciling conflicting evidence on the elasticity of ...

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472

0304-3932/$ -

doi:10.1016/j

$Special t

and commen

Lars Hansen

referee, as we

University, M

NBER Econ

Stanford SIT

Elasticity of�Correspo

C3100, BRB

E-mail ad

www.elsevier.com/locate/jme

Reconciling conflicting evidence on theelasticity of intertemporal substitution:

A macroeconomic perspective$

Fatih Guvenen�

Department of Economics, University of Rochester, 216 Harkness Hall, Rochester, NY 14627, USA

Received 21 March 2005; received in revised form 19 May 2005; accepted 24 June 2005

Available online 26 May 2006

Abstract

In this paper we reconcile two opposing views about the elasticity of intertemporal substitution

(EIS). Empirical studies using aggregate consumption data typically find the EIS to be close to zero,

whereas calibrated models designed to match growth and fluctuations facts typically require it to be

close to one. This contradiction is resolved when two kinds of heterogeneity are acknowledged: one,

the majority of households do not participate in stock markets; and two, the EIS increases with

wealth. We introduce these two features into a standard real business cycle model. First, limited

participation creates substantial wealth inequality as in the U.S. data. Consequently, the properties

of aggregates directly linked to wealth (e.g., investment and output) are mainly determined by the

see front matter r 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

.jmoneco.2005.06.001

hanks to Tony Smith and Per Krusell for their advice and encouragement. For helpful conversations

ts, I thank Daron Acemoglu, Aydogan Alti, Olivier Blanchard, Jeremy Greenwood, Robert Hall,

, Robert King (the Editor), Torsten Persson, David Laibson, Nick Souleles, Stan Zin, an anonymous

ll as the seminar participants at Carnegie-Mellon, Chicago GSB, IIES at Stockholm University, Koc

IT, Penn State, Queen’s, Richmond FED, Rochester, Sabanci University, Upenn, UCSD, the

omic Fluctuations and Growth Meeting, the Minnesota Macroeconomics Workshop, and the

E conference. An earlier version of this paper was circulated under the title ‘‘Mismeasurement of the

Intertemporal Substitution: The Role of Limited Stock Market Participation.’’

nding author at: Department of Economics, University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station,

3.118, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

dress: [email protected].

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721452

(high-EIS) stockholders. Since consumption is much more evenly distributed than is wealth,

estimation from aggregate consumption uncovers the low EIS of the majority (i.e., the poor).

r 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classification: E32; E44; E62

Keywords: The elasticity of intertemporal substitution; Limited stock market participation; Business cycle

fluctuations; Incomplete markets; Wealth inequality

1. Introduction

A rational agent will seize intertemporal trade opportunities revealed in asset prices byadjusting her consumption growth, by an amount inversely related to her (counteracting)desire for a smooth consumption profile. The degree of this consumption growth responseis called the elasticity of intertemporal substitution in consumption (EIS). Research inmany fields of macroeconomics has established the EIS as crucial for many questionsranging from the effects of monetary and fiscal policies to the determinants of long-runeconomic growth (see, for example, Summers, 1981; King and Rebelo, 1990; Jones et al.,1999). The goal of this paper is to use macroeconomic analysis to reconcile seeminglycontradictory evidence about the value of this parameter.On the one hand, macroeconomists generally use a value close to 1, reflecting the view

that a high degree of intertemporal substitution is more consistent with aggregate dataviewed through the lens of dynamic macroeconomic models. To illustrate some of thearguments, let us rearrange the consumption Euler equation to obtain

Rft ¼ Zþ ð1=EISÞ � logðCtþ1=CtÞ, (1)

where Z is the time preference rate. For convenience we abstracted from uncertainty.1

Given that the annual per-capita consumption growth in the U.S. is about 2%, anelasticity of 0.1 as estimated by Hall (1988) together with Z40 implies a lower bound of20% for the real interest rate! This observation is well known as Weil’s (1989) risk-free ratepuzzle. Alternatively, substituting a realistic average interest rate of 3%, and aconsumption growth of 2%, requires the EIS to be at least 0.66 if Z is to be positive. Infact, a similar observation has led Lucas (1990) to rule out an elasticity below 0.5 asimplausible (in his notation s � 1=EISÞ:

1The

and Zi

see, fo

If two countries have consumption growth rates differing by one percentage point,their interest rates must differ by s percentage points (assuming similar time discountrates). A value of s as high as 4 would thus produce cross-country interestdifferentials much higher than anything we observe, and from this viewpoint evens ¼ 2 seems high.

Similarly, Jones et al. (2000) have examined the volatilities of the macroeconomic time-series generated by a real business cycle model and concluded that they match the U.S.

following argument is robust to the introduction of uncertainty and generalizing preferences to the Epstein

n (1989) utility function, because an equation very similar to (1) can still be derived under these conditions;

r example, Attanasio and Weber (1989).

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1453

data the best when the EIS is calibrated to be between 0.8 and 1. For manymacroeconomists reasoning like these constitute convincing evidence that the EIS is quitehigh, probably close to 1.

On the other hand, an alternative approach is to use the conditional consumption Eulerequation, and estimate the EIS from the co-movement of aggregate consumption withasset returns (Hansen and Singleton, 1983; Hall, 1988). This line of research, however, hasreached a completely different conclusion. In an influential paper Hall (1988) has arguedthat consumption growth is completely insensitive to changes in interest rates and, hence,the EIS is very close to zero. The subsequent empirical macro literature has providedfurther support (see Campbell and Mankiw, 1989; Browning et al., 1999, and thereferences therein).2 Thus, there is an apparent contradiction between the dynamicmacroeconomics literature and econometric studies which both use aggregate data indifferent ways.

We show that this apparent inconsistency is largely a consequence of the ‘‘representativeagent’’ perspective widely adopted in both literatures. To this end, we study an otherwisestandard real business cycle model and introduce two key sources of heterogeneity: limitedparticipation in the stock market and heterogeneity in the elasticity of intertemporalsubstitution. A large body of empirical evidence will be presented in Section 3 documentingthese facts. Specifically, we consider an economy with neoclassical production andcompetitive markets. There are two types of agents. The majority of households (secondtype) do not participate in the stock market where one-period risky claims to the aggregatecapital stock are traded. However, a risk-free bond is available to all households, so non-stockholders can also accumulate wealth and smooth consumption intertemporally.Finally, consistent with the empirical evidence reviewed in Section 3, stockholders areassumed to have a higher EIS (around 1.0) than non-stockholders (around 0.1).

The main result of the paper can be explained as follows. In the model, limitedparticipation creates substantial wealth inequality matching the extreme skewnessobserved in the U.S. data. Consequently, the properties of aggregate variables directlylinked to wealth, such as savings, investment, and output, are almost entirely determinedby the (high-elasticity) stockholders who own virtually all the wealth (capital) in theeconomy. On the other hand, consumption turns out to be much more evenly distributedacross households, again as in the U.S. data, so aggregate consumption—and hence Eulerequation estimations—mainly reveal the low EIS of the majority, that is, the poor. As aresult, the model delivers several business cycle statistics that appear to be generated froma representative agent RBC model with an EIS of 1 (Section 4), while at the same time aHall-type Euler equation estimation uncovers an EIS of around 0.25 (Section 6).

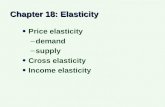

This explanation clearly relies on the premise that the average investor is very differentthan the average consumer. Section 4.1 documents the remarkably different concentrationsof wealth and consumption in the U.S. data. For example, the richest 20% own 83% of networth and 95% of financial assets, but account for only about 30% of aggregateconsumption (Fig. 1). Moreover, it is clear that the ability of the model to generate thissubstantial wealth inequality is crucial for our results, otherwise the average consumer andinvestor would be similar in the model. Further, since similar models with a dynasticstructure typically yield too little wealth inequality, Section 5 explains how theintroduction of limited participation into such a framework generates substantial

2We discuss some econometric studies which obtain higher estimates of the EIS below.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721454

heterogeneity. Finally, an appendix shows—in the context of a capital income taxationproblem—that policy conclusions drawn from a representative-agent model calibrated tothe EIS obtained from Euler equation estimations can be seriously misleading.

1.1. Related literature

This paper is related to two strands of literature. The first one, starting with aninfluential paper by Mankiw and Zeldes (1991), investigates the role of limited stockmarket participation in resolving asset pricing puzzles (Basak and Cuoco, 1998; Attanasioet al., 2002; Guvenen, 2004). However, despite the increasing number of studies in thisfield, the main focus so far has been on asset prices and less attention has been devoted tothe macroeconomic implications of this phenomenon which remain largely unexplored. Inthis paper we attempt to close this gap by studying the role of limited participation ingenerating inequality in wealth and consumption, and consequently, in shaping thedetermination of macroeconomic aggregates. A second literature estimates the EIS usingdifferent versions of the log-linearized Euler equation. Although some early studies(Summers, 1981; Hansen and Singleton, 1983) obtained estimates of the EIS around 1.0,Hall (1988) argued that these estimates were biased upward because of the timeaggregation in consumption data. More recently, Ogaki and Reinhart (1998) have arguedthat non-separability between durables and non-durables could bias the estimates of EIS,such as Hall’s (1988) in the opposite direction—downward—if not accounted for.Similarly, Basu and Kimball (2000) have shown that non-separability between consump-tion and leisure could create a similar downward bias. Both papers obtained estimates ofthe EIS around 0.35. Compared to these studies, this paper stresses a different economicpoint: even when the Euler equation is estimated without any problems, the resultingestimate of the EIS (which is necessarily an ‘‘average’’ of individual elasticities) is not theappropriate measure of elasticity for many questions, especially those related to savings,investment, and output.

2. The model

For transparency of results, our modeling goal is to stay as close to the standard realbusiness cycle framework as possible and only introduce the two key features discussedabove.

2.1. The firm

There is a single perishable consumption–investment good in this economy. The singleaggregate firm converts capital (Kt) and labor (Lt) inputs into output according to aCobb–Douglas technology: Y t ¼ ZtK

yt L1�y

t ; where y 2 ð0; 1Þ is the factor share parameter.The stochastic technology level Zt follows a first-order Markov process with a strictlypositive support. In the absence of any intertemporal links in the firm’s problem (such ascapital adjustment costs, etc.) the firm’s decision can be simply expressed as a series of one-period profit maximization problems:

MaxKt;Lt

½ZtKyt L1�y

t � ðRst þ dÞKt �W tLt�,

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1455

where Rst and W t are the market return on capital and the wage rate, respectively, and d is

the depreciation rate of capital.Finally, capital and labor markets are competitive implying that the factors are paid

their respective marginal products after production takes place:

Rst ¼ yZtðKt=LtÞ

y�1� d,

W t ¼ ð1� yÞZtðKt=LtÞy. ð2Þ

2.2. Households

We consider an economy populated by two types of agents who live forever. Thepopulation is constant and is normalized to unity. Let l ð0olo1Þ denote the measure ofthe first type of agents (who will be called ‘‘stockholders’’ later) in the total population.Both agents have one unit of time endowment in each period, which they supplyinelastically to the firm.

2.2.1. Preferences

Agents value temporal consumption lotteries according to the following Epstein–Zin(1989) recursive utility function:

Uit ¼ ½ð1� bÞðCtÞ

ji

þ bðEtðUitþ1Þ

1�aÞji=ð1�aÞ

�1=ji

; 0að1� aÞ; jio1 (3)

for i ¼ h, n. Throughout this paper the superscripts h and n denote stockholders and non-stockholders, respectively. The subjective time discount factor under certainty is given byb � 1=ð1þ ZÞ, and a is the risk aversion parameter for wealth gambles, common to bothtypes. The focus of attention in this paper is the EIS parameter which is denoted byri � ð1� jiÞ

�1and as the superscript i indicates, types may differ in their intertemporalelasticities.

Before proceeding further, it is important to stress that our choice of recursivepreferences is for clarity: by disentangling risk aversion and the elasticity of intertemporalsubstitution, this specification allows us to introduce heterogeneity in the EIS withoutgenerating corresponding differences in risk aversion. It is worth noting though that riskaversion plays little role in the model: even assuming CRRA utility delivers practically thesame results as long as the calibration of the EIS remains the same as here. Finally, notethat these preferences nest expected utility as a special case: when j ¼ 1� a, thisspecification reduces to the familiar CRRA expected utility function.

2.2.2. Stock market participation

Besides the productive capital asset there is also a one-period risk-less household bond(in zero net supply) that is traded in this economy. The crucial difference between the twogroups is in their investment opportunity sets: the ‘‘non-stockholders’’ can freely trade thebond, but they are restricted from participating in the capital market. The ‘‘stock-holders,’’ on the other hand, have access to both markets and hence are the sole capitalowners in the economy.3

3It is possible to think of the participation structure assumed here as the endogenous outcome of a model where

every period agents have the option of paying a one-time fixed cost of entering the stock market (if they had not

already done so in previous periods). With a cost of appropriate magnitude, the group of agents with high EIS will

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721456

Finally, we impose portfolio constraints as a convenient way to prevent Ponzi schemes.As we discuss later, for the main results of the paper these constraints need not bind; theycan be as loose as possible.

2.3. Households’ dynamic problem and the equilibrium

To state the individual’s problem recursively, the aggregate state space for this economyneeds to be specified. The Markov characteristic of the exogenous driving force naturallysuggests concentrating on equilibria that are dynamically simple. That is, we assume thatthe portfolio holdings of each group together with the exogenous technology shockconstitute a sufficient state space which summarizes all the relevant information for theequilibrium functions.In a given period, the portfolios of each group can be expressed as functions of the

beginning-of-period capital stock, K, the aggregate bond holdings of the non-stockholdersafter production, B, and the technology level, Z. Let us denote the aggregate state byY � ðK ;B;ZÞ, and the financial wealth of an agent by o where superscripts are suppressedfor clarity of notation. Given the recursivity of the utility and the stationarity of theenvironment, maximization of (3) for the stockholders can be expressed as the solution tothe following dynamic programming problem:

V ðo;YÞ ¼ maxC;b0 ;s0

ðð1� bÞðCÞj þ bðE½V ðo0;Y0Þ1�aj Z�Þj=ð1�aÞÞ1=j

s:t.

C þ qðYÞb0 þ s0 p oþW ðK ;ZÞ;

o0 ¼ b0 þ s0ð1þ RsðK 0;Z0ÞÞ;

K 0 ¼ GK ðYÞ;

B0 ¼ GBðYÞ;

b0

X Bh;

where b0 and s0 denote bond and stock (capital) choice of the agent, respectively. Theendogenous functions GK and GB denote the laws of motion for aggregate wealthdistribution which are determined in equilibrium, and q is the equilibrium bond pricingfunction. Note that each agent is facing a constraint on bond holdings with possiblydifferent (and negative) lower bounds. The problem of the non-stockholder can be writtenas above with s0 � 0.

A recursive competitive equilibrium for this economy is given by a pair of value functionsViðoi;YÞ ði ¼ h; nÞ, consumption and bondholding decision rules for each agent, Ciðoi;YÞand bi

ðoi;YÞ, stockholding decision for the stockholder, sðoh;YÞ, a bond pricing function,

(footnote continued)

enter the stock market whereas the other group will stay out. This is because, loosely speaking, agents with a low

EIS are reluctant to accumulate wealth quickly and hence their benefits from participation is lower than agents

with a high EIS. See the working paper version of this article for further discussion. In Guvenen (2004) we

quantify the magnitude of this participation cost in a version of this model with capital adjustment costs in

production. For the purposes of this paper, the present setup seems a reasonable simplification.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1457

qðYÞ, competitive factor prices, RsðK ;ZÞ, W ðK ;ZÞ, and laws of motion for aggregatecapital and aggregate bond holdings of non-stockholders, GK ðYÞ, GBðYÞ, such that:

(1) Given the pricing functions and the laws of motion, the value functions and decisionrules of each agent solve that agent’s dynamic problem.

(2) Factors are paid their respective marginal products (Eq. (2) is satisfied).(3) The bond market clears: lbh

ð$h;YÞ þ ð1� lÞbnð$n;YÞ ¼ 0, where $i denotes the

aggregate wealth of a given group; and the labor market clears: L ¼ l� 1þ ð1� lÞ�1 ¼ 1.

(4) Aggregates result from individual behavior:

K 0 ¼ lsð$h;YÞ, ð4Þ

B0 ¼ ð1� lÞbnð$n;YÞ. ð5Þ

3. Numerical solution and calibration

The model is solved using numerical methods since an analytical solution is notavailable. As usual the existence of aggregate shocks introduces an additional layer ofcomplexity. Instead of approximating the equilibrium functions around the stochasticsteady state (for example, as in Krusell and Smith, 1998) we solve for all the functionsglobally over the state space. Although this generality has additional computational costs,it also allows us to conduct policy experiments involving transitions (such as the capitalincome taxation problem studied in the Appendix) very easily. Moreover, to ourknowledge this is the first attempt at numerically solving a dynamic programming problemwith general recursive utility. A computational appendix available from the author’swebsite contains the algorithm as well as a discussion of the accuracy of the solution.

3.1. Baseline parameterization

The model parameters are chosen to replicate the long-run empirical facts of the U.S.economy. The time period in the model corresponds to one year of calendar time.Following Cooley and Prescott (1995) the capital share of output is set equal to 0.4. Thetechnology shock Z is assumed to follow a first-order, two-state Markov process withtransition probabilities pij ¼ PðZtþ1 ¼ j jZt ¼ iÞ chosen such that business cycles aresymmetric and last for 6 years on average. This condition implies p11 ¼ p22 ¼ 2=3. Themean of the technology shock is a scaling parameter and is normalized to 1. The standarddeviation of the technology shock, sðZÞ, is set equal to 3.1% which is the implied annualvolatility assuming that the quarterly Solow residuals follow an AR(1) process with apersistence of 0.95 and a coefficient of variation of 1%. We also investigate the sensitivityof the results to alternative calibrations.

3.1.1. Participation rates

Our model assumes a constant participation rate in the stock market, which appears tobe a reasonable approximation for the period before the 1990s when the participation ratewas either stable or increasing gradually (Poterba and Samwick, 1995). In contrast, duringthe 1990s participation increased substantially: from 1989 to 2002 the number ofhouseholds who owned stocks increased by 74%, and by 2002 half of the U.S. households

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721458

had become stock owners (Investment Company Institute, 2002). Modeling theparticipation boom in this later period would require going beyond the stationarystructure of our model, so we leave it for future work. In this paper, we calibrate theparticipation rate excluding this later period (1990 onward). We set the measure ofstockholders, l, equal to 30%, which roughly corresponds to the stock marketparticipation rate during the 1980s, when participation is defined as holding any positiveamount of stocks. A significant fraction of stockholders during this period owned no morethan a few thousand dollars worth of stocks (see again Poterba and Samwick, 1995), sothis percentage should probably be interpreted as an upper bound on the percentage ofhouseholds actively participating in the stock market. In the next section we also report theresults by assuming a participation rate of 15%.

3.1.2. Heterogeneity in the EIS

There is a fairly large and active literature documenting heterogeneity in the EIS. A firstgroup of papers consider flexible preference specifications allowing for non-homotheticityand estimate their parameters from the consumption Euler equation. Using this approach,Blundell et al. (1994) find that the EIS is monotonically increasing in income, and in somespecifications it is more than three times larger for the highest decile compared to thelowest decile. They also investigate heterogeneity in the EIS due to other factors butconclude that ‘‘most of the variation in the EIS across the population is due to differencesin consumption (which can loosely be thought of as a proxy for lifetime wealth) and not todifferences in demographics and labor supply variables’’ (p. 73). Similarly, Attanasio andBrowning (1995) confirm this finding by employing an even more general functional form,although they do not report point estimates for the EIS.4 Since stockholders are on averagemuch wealthier than the rest of the population, the finding that elasticity is increasing inwealth also provides evidence of heterogeneity between the EIS of stockholders and others.A second group of papers focus directly on stockholders and non-stockholders and

estimate a separate elasticity parameter for each group (assuming homothetic preferenceswithin each group). For example, Attanasio et al. (2002) use the Family ExpenditureSurvey data set from the U.K. and obtain elasticity values around 1 for stockholders, andbetween 0.1 and 0.2 for non-stockholders. Vissing-Jørgensen (1998) obtains very similarestimates from the Consumer Expenditure Survey data on U.S. households.With Epstein–Zin preferences, the risk aversion and the EIS can be calibrated

independently of each other. For transparency of results, we abstract from heterogeneityin risk aversion and set ah ¼ an ¼ 3, which is within the range viewed as plausible by manyeconomists. This allows us to focus purely on the effects of heterogeneity in the elasticity ofsubstitution. In light of the empirical evidence reviewed above, the EIS of the non-stockholders is set equal to 0.1, and the EIS of the stockholders to 1.0.

4It is possible to give some theoretical justifications for why the EIS may increase with an individual’s wealth

level. For example, if individuals consume a variety of goods with different income elasticities, the intertemporal

elasticity of the total consumption bundle will be higher for wealthier individuals. This is because the share of

necessity goods in total consumption is large when the individual is poor, making her less willing to substitute

these necessities across time. In contrast, wealthy individuals will have a larger fraction of luxury goods in their

bundle, which are more easily substituted across time (see Browning and Crossley, 2000, for a proof). Similarly,

non-homotheticity in preferences due to subsistence requirements, habit formation and so on also typically implies

a higher EIS for the wealthy.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1459

Finally, the subjective discount factor, b, is set equal to 0.96 in order to match the U.S.capital–output ratio of 3.3 reported by Cooley and Prescott (1995).

3.1.3. Borrowing constraints

These bounds are chosen to reflect the fact that the stockholders can potentiallyaccumulate capital which can then be used as collateral for borrowing in the risk-free asset,whereas the non-stockholders have to pay all their debt through future wages. In thebaseline case, the stockholders’ borrowing constraint is set equal to four years of expectedlabor income ðBh ¼ 4� EðW ÞÞ. The borrowing limit of the non-stockholders is set to30% of one year’s expected income, which is the average credit limit typically imposedby short-term creditors, such as credit card companies. Table 1 summarizes the baselineparameterization.

4. Macroeconomic results

This section quantitatively examines if limited participation and heterogeneity in theEIS can explain the conflicting evidence discussed in the Introduction. Our main argumentis that the majority of the population with low elasticity has quantitatively little effect onaggregates directly linked to wealth, such as investment and output, which are determinedby the high elasticity of the wealthy stockholders. On the other hand, aggregateconsumption mainly reveals the preferences of the poor, who contribute substantially.Clearly, this argument relies on the idea that the average investor is significantly differentthan the average consumer violating the representative-agent assumption. Thus, it isimportant to characterize the joint distribution of consumption and wealth in the U.S. datato document that empirically this is indeed the case.

4.1. The empirical joint distribution of consumption and wealth

Table 2 reports the fraction of aggregate consumption and wealth accounted for bydifferent percentiles of the wealth distribution calculated from the Panel Study of IncomeDynamics (PSID) data set.5 The first three rows display the size distributions of differentmeasures of wealth, from the most comprehensive measure in the first row (net worth) tothe most specific in the third (financial assets).6 The intermediate measure, which we call

5Because we are interested in both wealth and consumption, we use the PSID instead of, for example, the

Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which contains more detailed information about wealth but no

consumption data, or the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE), which has detailed consumption data but no

comparable information on wealth holdings. One drawback of PSID is that consumption is limited to food

expenditures and rent payments. We take the sum of these two components (which makes up about 40% of non-

durables and services expenditures) as our consumption proxy in Table 2. The ratio of this proxy to the non-

durables and services expenditures from the CE is roughly constant across income deciles, which suggests that it

could provide a reasonable approximation to the distribution of this more general consumption measure. A data

appendix, available from the author’s website, provides further details about the construction of the consumption

proxy and discusses how it compares to the CE data. Moreover, the size distributions of both wealth measures are

quite similar to those reported by Wolff (2000) using data from the SCF.6‘‘Net worth’’ is defined as the current value of all marketable or fungible assets less the current value of debts.

Specifically, it includes: (1) the net equity in owner-occupied housing; (2) other real estate; (3) cash and demand

deposits; (4) time and saving deposits, CDs and money market accounts; (5) government bonds, corporate bonds

and other financial securities; (6) cash surrender value of life insurance policies; (7) cash surrender values of

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 1

Baseline parameterization

Annual model

Parameter Value

b Time discount rate 0.96

ah Risk aversion of stockholders 3

an Risk aversion of non-stockholders 3

rh EIS of stockholders 1

rn EIS of non-stockholders 0.1

l Participation rate 0.3

p11 Prob (good state j good state) 2/3

p22 Prob (bad state j bad state) 2/3

sZ Standard deviation of Z 0.031

y Capital share 0.4

d Depreciation rate 0.08

Bh Borrowing limit of stockholders 4W

Bn Borrowing limit of non-stockholders 0:3W

Note: The mean of the technology shock is a scaling parameter and is normalized to 1. The borrowing limits are

indexed to the average wage rate, W .

Table 2

The concentration of wealth and consumption

Percentage share of ‘‘variable’’ held by wealth percentiles

U.S. data Model

Wealth percentile 1–10 11–30 31–50 51–100 1–30 1–30 31–100

Variable

Net worth 0.702 0.181 0.087 0.030 0.883 0.89 0.11

Productive wealth 0.742 0.201 0.054 0.002 0.942 0.89 0.11

Financial assets 0.832 0.210 0.026 �0.068 1.043 0.89 0.11

Consumption 0.169 0.251 0.205 0.373 0.429 0.37 0.63

Notes: The data are drawn from the 1989 PSID family file and wealth supplement. All variables are defined at

household level. The consumption measure is a proxy constructed from food expenditures and rent as explained in

footnote 5. Productive wealth is defined as net worth minus equity in owner-occupied housing, where net worth

and financial assets are defined in footnote 6.

F. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721460

‘‘productive wealth’’ for lack of a better term, is defined as net worth minus equity inowner-occupied housing. We use these three measures to show that the general conclusionsdrawn about the concentration of wealth are not sensitive to the specific definition of

(footnote continued)

pension plans, including IRAs, Keogh and 401(k) plans; (8) corporate stocks and mutual funds; (9) net equity in

unincorporated businesses; and (10) equity in trust funds. From the sum of these assets we subtract consumer debt

including auto loans and others. ‘‘Productive wealth’’ is the sum of (2)–(10). The narrowest definition is ‘‘financial

wealth,’’ and is the sum of (3)–(8).

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1461

wealth used. Finally, the last row displays the share of aggregate consumption accountedfor by households in different percentiles of the productive wealth distribution.

The main observation from this table is that all three measures of wealth displaysubstantially higher concentration than consumption: households in the top 10% of thewealth distribution own three-quarters of aggregate productive wealth but account foronly about 17% of total consumption in the U.S. data.7 By also including the next decile(top 20%), this group of households can be thought of as the ‘‘investors’’ since they holdabout 90% of capital and land, and virtually all financial assets. In contrast, observe thevery gradual decline in consumption expenditures moving down the wealth distribution.The bottom 80% own only 12% of productive wealth, yet contribute almost 70% of totalconsumption. Thus this latter group can be thought of as the ‘‘consumers.’’ Expressing thesame information in per capita terms makes this distinction even more striking: an averageinvestor owns 29.3 times the productive wealth of an average consumer, but consumes only1.7 times more. These two groups are also marked in Fig. 1 (which plots the jointdistribution) to give a visual impression of their dramatically different contributions toaggregate consumption and wealth.8 Moreover, the richest 30%—who own 99% of stocksbefore the 1990s, and hence whom we identify with the stockholders—held 88% of networth and more than 100% of financial assets.

The fact that consumption is more evenly distributed than physical wealth is not totallysurprising, since consumption is proportional to lifetime wealth inclusive of human capital,which constitutes a substantial part of lifetime wealth and is more evenly distributed thanphysical capital. As we shall see below, the limited participation model generates the samekind of wealth and consumption distributions and thus captures this key component inexplaining the evidence on the EIS.

4.2. Results from the baseline economy

Given how remarkably different the average consumer and the average investor are, itmight seem almost obvious that each of these groups will (largely) determine differentaggregates, and together with the heterogeneity in the EIS across these two groups, areconciliation of the evidence on the EIS would seem to follow immediately. Why is it thennot sufficient to merely document these two kinds of heterogeneity in the data to qualify asa full explanation?

The reason is the existence of trade in the bond market, which provides a channelthrough which the non-stockholders’ preferences can potentially influence the properties ofaggregate quantities, including investment and output. For example, in a companion paperusing essentially the same model (augmented with capital adjustment costs in production)we found that the non-stockholders’ preferences—and their low EIS in particular—play akey role in determining asset prices despite the fact that they hold very little wealth in that

7One drawback of existing micro-data sets containing consumption data is that they tend to underrepresent

very rich households (i.e., those in the top 1% of the wealth distribution). As a result, stockholders’ consumption

is likely to be somewhat understated to the extent that the consumption of these very rich households are not

captured.8Fig. 1 also makes clear that there is substantial heterogeneity among the very wealthy as well. Thus, while in

the baseline parameterization we take the fraction of stockholders to be 30%, most of the wealth is in fact held by

a subset of these households. In the next section we experiment with a lower participation rate of 15% to examine

whether it makes a difference in our results.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

Fraction of Aggregate Consumption

Frac

tion

of A

ggre

gate

(Pr

oduc

tive)

Wea

lth

Investors(Top 20%)

Consumers(Lower 80%)

Fig. 1. The fraction of aggregate consumption accounted for by households who own a given fraction of

aggregate wealth.

F. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721462

model as well (Guvenen, 2004). Thus, it is essential to investigate the behavior ofaggregates allowing for equilibrium interactions through the bond market, which is donein this subsection.We begin by comparing the cross-sectional distributions of consumption and wealth

generated by the model to their empirical counterparts documented above. With only twotypes of agents, the model generates two-point distributions for each variable reported inthe last two columns of Table 2. First, the wealth distribution is extremely skewed in themodel, with 89% of aggregate wealth owned by the stockholders, similar to the share ofwealth owned by the top 30% in the U.S. data. And second, consumption is much moreevenly distributed, with 37% of aggregate consumption accounted for by the stockholdersin the model, compared to 43% in the data. So, the model is able to generate thesignificantly different concentrations of these two variables, which is an essential elementin our explanation of the evidence on the value of the EIS.We now examine the implications of the limited participation model for business cycle

statistics. The first row of Table 3 reports the standard deviations and the first-orderautocorrelations of aggregate output (GDP), investment and consumption from the U.S.data. First, in order to see why a low EIS seems difficult to reconcile with aggregatefluctuations, consider the statistics reported on row 2 from a representative agent RBCmodel with an EIS of 0.1, which otherwise has the same parameterization as the baselinelimited participation model. Notice that while the volatility of consumption matches itsempirical counterpart, the volatilities of output and investment are overstated. Theexplanation is simple: because the agent desires a very smooth consumption path,investment has to absorb the shock to her income, making the former smooth at theexpense of extra volatility in investment, and consequently, in output. Moreover, all threevariables are too persistent.The third row reports the results when the EIS of the representative agent is raised to

1.0. The implications of the model move closer to data: output and investment become less

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 3

Business cycle statistics

Standard deviation (%) Autocorrelation

Y I C Y I C

(1) U.S. data 2.2 8.5 1.5 0.52 0.36 0.57

Models Panel A: Baseline parameterization

(2) RA ðEIS ¼ 0:1Þ 3.6 10.8 1.5 0.65 0.49 0.98

(3) RA ðEIS ¼ 1:0Þ 3.0 8.7 1.7 0.52 0.33 0.94

(4) Limited participation 3.0 8.8 1.5 0.53 0.36 0.96

Panel B: Fraction holding stocks is 15%

(5) Limited participation 3.1 8.9 1.5 0.54 0.37 0.96

Panel C: Business cycle duration is 8 years

(6) RA ðEIS ¼ 0:1Þ 4.1 11.3 1.9 0.76 0.63 0.98

(7) RA ðEIS ¼ 1:0Þ 3.4 9.1 2.1 0.65 0.45 0.95

(8) Limited participation 3.5 9.4 2.0 0.67 0.47 0.96

Notes: The empirical statistics of the U.S. economy are computed from the National Income and Product

Accounts data at yearly frequencies covering 1959:1999. All variables are first logged and the trend is removed

with Hodrick–Prescott filter with a smoothing parameter of 100. The consumption measure consists of

expenditures on non-durables and services. In Panel B, the borrowing constraint of stockholders is increased to

8� W to keep the total wealth that can be accumulated by the non-stockholders unchanged from the baseline

case.

F. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1463

volatile, without a major change in consumption volatility. The persistence of output andinvestment also come closer to their empirical counterparts. While the persistence ofconsumption falls slightly, it is still significantly higher than in the data.

The fourth row displays the moments from the baseline model. Comparing thesestatistics to those on the previous two rows, it is clear that the limited participation modelbehaves like the representative agent model with a high EIS (row 3) when output andinvestment are concerned. It is interesting that the existence of many households with a lowEIS has almost no effect on the properties of investment and output. In fact, the next rowreports the results when the participation rate is reduced to 15%, which shows noappreciable change in the behavior of output and investment. As for consumption, theunconditional moments examined here do not appear to be very sensitive to the EISparameter.

To examine the robustness of this conclusion, we have experimented with a number ofchanges in the baseline parameterization such as increasing the persistence and variance ofaggregate shocks, reducing the participation rate (discussed above), and relaxing the non-stockholders’ borrowing constraints to 4 years’ of expected income. As an example, rows6–8 report the results when the business cycle duration is increased to 8 years from itsbaseline value of 6. The pattern seen here applies to the other exercises described: theproperties of output and investment mainly reflect the high EIS of the stockholders, whilethe statistics for consumption are not very sensitive to the value of the EIS. However, the

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721464

co-movement of consumption growth with returns is informative about the value of theEIS parameter, which is further analyzed in Section 6.9

4.3. Heterogeneity in the EIS: further evidence

Our motivation for heterogeneity in the EIS came from a large empirical literature,which was discussed in Section 3. However, a potential caveat in that empirical evidence ispointed out by Laibson et al. (1998). Their argument can be summarized as follows.Suppose that there are two agents, a wealthy and a poor, who both have the same EIS. Ifthere are borrowing constraints which frequently bind for the poor agent, her consumptionwill closely track her income and will not respond to the interest rate unlike theconsumption of the wealthy (and unconstrained) agent. When the elasticities are recoveredfrom consumption data on these two agents, the poor one will appear as if she has a lowEIS. If true, then contrary to what we have assumed, there may not be any significantheterogeneity in the EIS in the first place.To further examine the evidence on the heterogeneity in the EIS we first turn to cross-

sectional data. An empirically well-documented difference between the stockholders andthe non-stockholders is that the consumption growth of the former is more volatile thanthat of the latter: the ratio of the variances of consumption growth, s2ðDchÞ=s2ðDcnÞ,ranges from 2 to 4 depending on the consumption measure and the threshold stockholdinglevel used to identify the two groups.10 This finding seems somewhat surprising though.Given that the stockholders are much wealthier than the rest and have access to financialmarkets, and low-income households typically have higher unemployment risk and laborearnings uncertainty, one might expect the former group’s consumption to be smootherthan that of the latter. In fact, it can easily be shown that a standard heterogenous-agentmodel with identical preferences and borrowing constraints (as in Aiyagari, 1994) wouldpredict exactly that: because poor households cannot self-insure as effectively as thewealthy, they keep hitting their borrowing constraints. Thus their consumption will tracktheir income and will be very volatile, contradicting this stylized fact.In fact, a similar result is obtained in the limited participation model if preference

heterogeneity is ignored: when we set rh ¼ rn ¼ 1, the ratio of the variances ofconsumption growth is 0.85, significantly lower than in the data. We have experimentedwith varying the shock size and its persistence, replacing the Markov structure with AR(1)shocks, and changing the calibration of constraints, without a noticeable increase in thisratio. Therefore, limited participation alone does not account for this fact. However, whenwe set rn ¼ 0:1, this picture changes. Now, the non-stockholders’ stronger desire for asmooth consumption path causes them to trade vigorously in the bond market driving theinterest rate down, and increasing the equity premium. Now, the non-stockholders’

9We do not examine a broader set of business cycle statistics, such as the behavior of labor hours, etc., because

the model is not designed to address those issues. It is of course possible to extend the model to investigate those

questions but that would require us to take a stand on further differences between the stockholders and the non-

stockholders (such as whether or not they differ in their labor supply elasticities, etc.) which would distract from

the main point of the paper.10Mankiw and Zeldes (1991) and Poterba and Samwick (1995) document this finding from the PSID, Vissing-

Jørgensen (1998) reports from the CEX, Attanasio et al. (2002) calculate from the Family Expenditure Survey

data set from U.K.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1465

consumption is smoother than that of the stockholders, who bear extra consumptionvolatility. As a result, s2ðDchÞ=s2ðDcnÞ rises from 0.85 to 3.73.

Second, a number of financial statistics implied by the model are very sensitive to theEIS of the non-stockholders and hence make sharp predictions about its value. We studythese asset pricing implications in Guvenen (2004). We find that, starting from an EISvalue of 1 for both agents, the performance of the model improves dramatically as the non-stockholders’ EIS is gradually reduced. For rn � 0:05� 0:2, the model is able to match avariety of asset pricing phenomena, including all the facts explained by the benchmarkmodel of Campbell and Cochrane (1999). Examples in this list include a high equitypremium, a low risk-free rate, the predictability of stock returns, the countercyclicality ofthe equity premium, among others. Given that many of these asset pricing phenomenahave been considered puzzles, these findings provide further support to the thesis that thenon-stockholders have a low EIS.

5. What is the effect of limited participation?

As noted earlier, the substantial wealth inequality is the driving force behind the resultsin this paper. This section examines the role played by limited participation in creating thiswealth inequality. This is especially important because the severity of the restrictionimposed by shutting some agents out of the stock market is not a priori obvious, since theonly source of risk in the model is an aggregate shock with relatively low variance andpersistence, and the non-stockholders still have access to the bond market. One couldtherefore suspect that some other feature of the model—such as the Epstein–Zinpreferences, heterogeneity in the EIS, or borrowing constraints—is behind the wealthinequality.

To study the role of limited participation, in isolation, the following experiment isconducted. First, consider a simplified version of the baseline model where all the frictionsand the preference heterogeneity is eliminated. More specifically, suppose that agents haveCRRA utility with rh ¼ rn ¼ 1; both agents have access to all markets and face noportfolio constraints. Clearly, this economy will reduce to a representative-agent model,and assuming that both agents start out at the same wealth level, there will be no trade inthe bond market, no wealth inequality, and no heterogeneity at all.

Now consider introducing a single friction into this framework: suppose that the secondgroup of agents are restricted from participating in the stock market (but otherwise imposeno other constraint). As Table 4 shows, the effect of this simple change is striking.Suddenly the stockholders come to hold almost 80% of the aggregate wealth (compared to30% without limited participation, since there was no wealth inequality in that case), or inper-capita figures, a stockholder now owns nearly eight times the average wealth of a non-stockholder. They also consume nearly 50% more per-capita than the non-stockholders.Furthermore, the two groups’ wealth holdings are now virtually uncorrelated, down fromperfect correlation with full participation. This example demonstrates the potential oflimited participation for generating substantial cross-sectional heterogeneity.

5.1. Where does the wealth inequality come from?

It is useful to begin by discussing how the wealth inequality in not generated. First, it isnot generated by the parameterization of preferences. Although preference heterogeneity

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 5

Wealth inequality for various parameter values

Parameters Share of wealth held by

EISh EISnRRAh RRAn Stockholders Non-stockholders

1.0 0.1 3.0 3.0 0.88 0.12

1.0 1.0 3.0 3.0 0.85 0.15

1.25 0.25 2.0 7.0 0.87 0.13

0.33 0.33 2.0 2.0 0.85 0.15

0.33 0.14 2.0 4.0 0.86 0.14

Note: r and a denote the EIS and relative risk aversion coefficients, respectively.

Table 4

The effect of limited participation on cross-sectional heterogeneity

Statistics in a limited participation model with otherwise identical agents

Stockholders Non-stockholders

Share of aggregate wealth 0.78 0.22

Per-capita wealth 8.27 1.00

Per-capital consumption 1.48 1.00

Std. of log consumption 0.018 0.019

Correlation of consumption with income 0.44 0.77

Cross-correlation between the two groups’:

Consumption Income Wealth

0.72 0.87 0.04

Notes: To make comparison across columns easier, the per-capita wealth and consumption of the non-

stockholders are normalized to 1.

F. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721466

has some effect on the distribution of wealth, this effect is modest for plausible changes inthe EIS parameter as well as in the risk aversion. This can be seen in Table 5 where theEIS varies from 0.1 up to 1.25, and the risk aversion varies from 2 to 7, without asubstantial change in inequality.Second, the wealth inequality is not generated by assumption, which is the case with a

limited participation model in an exchange economy setting. In that framework, thestockholders are endowed, at time zero, with the entire future stream of dividends inaddition to their labor income, and hence, are wealthier by assumption. In contrast, in thepresent model even when both agents start at the same wealth level, the stockholderschoose to accumulate more wealth in equilibrium. Furthermore, there is nothing inprinciple that prevents the stockholders from having zero wealth in equilibrium despite thefact they must own all the capital stock: a stockholder could borrow in the bond marketand invest all the proceeds in the firm, then pay the non-stockholder after production andconsume the equity premium. So, the stockholders are not wealthier simply because theyown the total capital stock. Then why are they?The basic mechanism can be described as follows. For the sake of discussion, consider a

simplified version of the limited participation model without preference heterogeneity, and

ARTICLE IN PRESS

−5 0 5 10 15 200

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

Asset Demand

Ass

et R

etur

n

Stockholders’wealth

Nonstockholders’wealth

RfRs

−Bmin

Long-Run Asset Demand Scheduleη: Time preference rate

Fig. 2. Long-run wealth distribution in the presence of return differences (limited participation).

F. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1467

where both agents face the same portfolio constraints on their bond holdings.11 Thesefeatures are not primary determinants of wealth inequality as noted above, and thismodification simplifies the following discussion.

In this environment, with infinite horizon and incomplete markets, both assetsearn average returns below the time preference rate. A well-known result in thisframework is that the wealth holdings of an agent will go to infinity if the (geometric)average of return is equal to the time preference rate.12 This result also holds when assetreturns are stochastic (Chamberlain and Wilson, 2000). Similarly, by a continuityargument, one can show that asset demand becomes unbounded as the average returnapproaches the time preference rate from below. Fig. 2 plots the typical long-run assetdemand schedule for an agent in this environment and illustrates the extreme sensitivity ofasset demand to small variations in returns near Z.13 The key feature of the baseline modelis that both the stock and the bond return are close to the time preference rate, so agentsare in this flat region of the asset demand schedule. Furthermore, the equilibrium stockreturn is much closer to the time preference rate than is the bond return:Z� EðRf Þ ¼ 17:8� ðZ� EðRsÞÞ. This last observation, combined with the fact that theequilibrium returns Rs and Rf are on the flat section of the asset demand schedule, explainswhy stockholders who have access to the slightly higher return, Rs, are willing to holdmuch more wealth than non-stockholders.

11It should be noted that borrowing constraints also contribute to the skewness of the wealth distribution. The

non-stockholders can save only up to the maximum amount the stockholders are allowed to borrow. When the

stockholders come closer to their borrowing constraints, this puts a downward pressure on bond return reducing

the nonstockholders’ demand for wealth. But as the example in Table 4 demonstrates, the concentration of wealth

is still substantial without any constraints.12See, for example, Aiyagari (1994) and references therein.13Note that the stockholders and the non-stockholders will still have different asset demand schedules (despite

having the same preferences and facing the same borrowing constraints) because of differences in their investment

opportunity sets. For the parameterizations used in this paper, this difference in asset demand schedule turns out

to be small, so we plot the same graph for both agents in Fig. 2.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721468

Finally, the graph also makes clear that the wealth inequality cannot be simply explainedby the argument that the stockholders have access to a positive equity premium and, hence,they are bound to become very wealthy in the long-run. This is because the equilibriumasset returns could very well lie in the steep region of the asset demand schedule, resultingin little wealth dispersion despite a positive equity premium.A second, and probably more intuitive, way to explain this mechanism is as follows.

With incomplete markets both agents want to accumulate precautionary wealth, and thisincentive is stronger for the non-stockholders who only have access to one asset. However,the only way this group can accumulate wealth (bond) is if stockholders are willing toborrow. In contrast, the stockholders have access to capital accumulation, and they couldsmooth consumption even if the bond market was completely shut down (just as arepresentative agent would do in the standard RBC model). Furthermore, the assetdemand of the non-stockholders is even more inelastic because, in addition, they have alow EIS and hence have a very strong desire for a smooth consumption profile. Therefore,trade in the bond market for consumption smoothing is more important for the non-stockholders than for the stockholders. As a result, the stockholders will only trade in thebond market if they can borrow at a low interest rate. This low interest rate in turndampens the non-stockholders’ demand for savings further, and they end up with littlewealth in equilibrium (and the stockholders end up borrowing very little).The described mechanism also corresponds to an argument commonly given for wealth

inequality, but to our knowledge, which has not been formally investigated in a generalequilibrium framework: the wealthy become wealthy because they face higher returns. Thisis exactly what happens in this model.

6. Another side of the puzzle: the empirical estimates of the EIS

We now look at the model economy through the lens of empirical macro-studies andshow that the aggregate consumption data reveals the low EIS of the majority, i.e., thepoor. Using simulated data we replicate existing studies which estimate the EIS from thelog-linearized consumption Euler equation (Hansen and Singleton, 1983; Hall, 1988;Campbell and Mankiw, 1989, among others). The estimated equation is

Dctþ1 ¼ k þ rrft;tþ1 þ �tþ1, (6)

where small letters denote the natural logarithms of variables, D is the difference operator,

k � r logðbÞ þ1

2rvartðDctþ1Þ

� �,

and �tþ1 is the agent’s forecast error with zero mean conditional on current information:Eð�tþ1jOtÞ ¼ 0.Eq. (6) is estimated via instrumental variables (IV) method using instruments commonly

used in the literature. Specifically, our instrument set is an ð8� 1Þ vector that consists ofthe lags of consumption growth and the risk-free rate: (1, Dci

t�1, Dcit�2, Dci

t�3, Dcit�4, r

ft�2,

rft�3, r

ft�4), where i ¼ h; n or A (referring to aggregate consumption) depending on whether

Eq. (6) is estimated using the consumption of the stockholders, the non-stockholders, orthe aggregate. Finally, we concentrate on large sample results, so a sample path of 63,000observations is simulated and the first 3,000 periods are discarded.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 6

Estimation of the log-linearized Euler equation with risk-free return

Non-stockholder Stockholders Aggregate

True value of EIS 0.10 1.00 0.47

kf¼ constant

EIS 0.11 0.54 0.25

(t-stats) (22.15) (51.1) (36.82)

kf¼ constant þð1=2rÞ � vartðDctþ1Þ

EIS 0.101 1.07 0.48

(t-stats) (17.02) (27.96) (21.84)

F. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1469

In the first step, the estimation is performed by assuming that the intercept term k isconstant through time (or equivalently, that it is uncorrelated with the instruments). Whilethis assumption is almost unanimously made in the empirical macro-literature, it will turnout to significantly affect the results. The first column of Table 6 reports the estimated EISparameter of each group (estimated using that group’s consumption data) as well as for theaggregate (rA). Although with incomplete markets there is no explicit mapping fromindividual elasticities into rA, one can show that the latter will be close to a consumption-weighted average of each group’s EIS: rA � ððlC

h=C

AÞrh þ ðð1� lÞC

n=C

AÞrnÞ, where the

bars indicate time averages of each variable.14This average in the baseline model is 0.47.However, the estimated value is 0.25, almost half of that figure.

One possible candidate for this bias is the omission of the conditional variance term k

from the regression because in simulated data it is significantly (negatively) correlated withthe instruments (lagged interest rates). Thus, we re-estimate (6Þ by properly including thetime-varying conditional variance calculated from the model’s optimal decision rules. Theeffect is dramatic: the aggregate EIS now jumps to 0.48, which is almost exactly theconsumption-weighted elasticity. This exercise suggests that, to the extent that our modeleconomy is able to capture the dynamics of these variables in the data, the previousestimates of the EIS are likely to be downward biased.15

14To see this simply note that logðCAtþ1=CA

t Þ ¼ logð1þ ðlDChtþ1 þ ð1� lÞD Cn

tþ1Þ=CAt Þ � lDCh

tþ1=CAt þ ð1� lÞ

DCntþ1=CA

t � Dchtþ1 ðlCh

t =CAt Þ þ Dcn

tþ1ðð1� lÞCnt =CA

t Þ. This last expression is the weighted sum of the left hand

side of Eq. (6) for the stockholders and the non-stockholders, where the weights are proportional to each group’s

contribution to aggregate consumption. If these weights do not change much over time, or are uncorrelated with

the instruments, the estimated parameter on the right hand side will approximately be the same weighted average

of the group-specific EISs, where the weights are replaced by their time averages.15In principle, one can apply the same correction described here (by including the conditional variance of

consumption growth) to the Euler equation estimations in the literature, such as Hall’s (1988). In practice,

however, computing the empirical conditional variance is not as straightforward as in the model (where we have

access to individuals’ explicit decision rules). To gain an idea about the potential empirical importance of this

correction, we constructed a simple measure of vartðDctþ1Þ for each t, by calculating the rolling sample variance of

consumption growth in the subsequent N periods. Including this term increases the estimate of the EIS from

roughly zero to 0.3–0.6 range (depending on the choice of N, and the instrument set used) with an average slightly

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721470

7. Conclusion

In this paper we attempted to reconcile two seemingly contradictory views about theelasticity of intertemporal substitution. A number of observations on growth andaggregate fluctuations suggest a value of EIS close to 1. In contrast, the co-movementbetween aggregate consumption and interest rates—the focus of the empirical consump-tion literature—implies a very weak relationship between the two, suggesting an elasticityclose to zero.We showed that a simple and otherwise standard real business cycle model featuring

limited participation in the stock market and heterogeneity in the elasticities is able toproduce findings consistent with both capital and consumption fluctuations. In otherwords, an economy where the majority of households exhibit very low intertemporalsubstitution is consistent with aggregate capital and output fluctuations as long as most ofthe wealth is held by a small fraction of population with a high EIS. In this model limitedparticipation in the stock market creates substantial wealth inequality similar to thedistribution of wealth between the stockholders and the non-stockholders in the data.(This is in contrast to the majority of dynastic models which are known to generate littlewealth dispersion, and hence suggests limited participation as an important factor inunderstanding distributional issues.) Consequently, the properties of output andinvestment are almost entirely determined by the high-elasticity stockholders, whereasconsumption is strongly affected by the inelastic non-stockholders who contributesubstantially. This dichotomy explains how the preferences of wealthy are hardlydetectable in consumption data but still strongly influence the economy’s aggregates.The cross-sectional richness of the model allowed us to address related questions. For

example, if the low EIS estimates of the poor were indeed due to severe borrowingrestrictions instead of genuine preference heterogeneity (as argued by some papers), such amodel would have implications inconsistent with cross-sectional and asset price data. Onthe other hand, the current model explains those facts when preference heterogeneity isproperly acknowledged, providing further support to the thesis the poor have low EIS.The idea that aggregates can be better explained by the interaction of heterogenous

agents rather than by a representative agent’s intertemporal problem with a variety offrictions has important consequences. For example, in a representative-agent economyaggregate consumption and savings are determined by the very same preferences, whereasin the current model, they are significantly different from one another. We conclude that,as a result, economic analyses as well as policy discussions based on average elasticitiesmay be seriously misguided.

Appendix A. Policy implications

In the foregoing analysis our goal has been to demonstrate the interaction betweenwealth inequality and heterogeneity in the EIS from a positive perspective. We nowconduct a policy experiment to demonstrate that one can reach misleading policyconclusions if this heterogeneity is ignored.

(footnote continued)

higher than 0.4. To save space, these further results are reported in an appendix available from the author’s

website.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–1472 1471

It has long been recognized in the public finance literature that the welfare effects ofcapital income taxation critically depend on the degree of intertemporal substitution(Summers, 1981; King and Rebelo, 1990). Indeed, Hall (1988) concludes that his estimateof a small EIS also imply a weak response of savings to changes in interest rates. To thecontrary, we argue that the effect of taxation on savings will be determined by the wealth-weighted average elasticity measure, which is—given the enormous wealth inequality—very close to that of the stockholders.

In order to demonstrate this point, we study a simple tax reform problem similar to theone studied by Lucas (1990). Imagine that initially the government imposes a flat-rate taxon capital income and returns the proceeds to households in a lump-sum fashion. At acertain date, capital income tax is completely eliminated and agents have not previouslyanticipated it. The initial tax rate is set equal to 36% which roughly corresponds to theaverage rate in the U.S. All aspects of the baseline model remain intact.

In order to provide a comparison to the existing literature, we first consider the welfaregain from this reform in a representative-agent framework. If the agent has r ¼ 1:0, thewelfare benefit of this policy is 0.93% of consumption per period—taking the transitionpath into account. Although it may not seem much, as Lucas argues, this is about 20 timesthe gain from eliminating the business cycle fluctuations, and two times the gain fromeliminating 10% inflation rate. However, if we assume that the agent has r ¼ 0:1, thewelfare gain is reduced to 0.4% of consumption instead, mainly because now the transitiontakes about 110 years compared to about 23 years in the former case.

Now suppose that the limited participation economy is subjected to the same taxexperiment. The welfare gain is 0.82% of total consumption.16 In effect, this economybehaves as if it was populated only by agents with unit elasticity and non-stockholders’preferences virtually vanished from the problem.

There is an even more interesting side to this problem that transpires from explicitlymodeling heterogeneity: based on policy experiments like the one above, some economistshave argued in favor of eliminating capital income taxes. But, a representative-agentframework masks the question of ‘‘who gains and who loses from this reform?’’ In reality,all agents are not identical, and as we have shown so far, in some dimensions, they differsubstantially. So, it is compelling to take this question seriously and break down the gainsfrom this reform. It turns out that, in consumption terms, the stockholders gain by 5.4%,whereas the non-stockholders, who constitute 70% of the population, actually lose 2.1%of their consumption. Clearly, this is a different conclusion than what comes out from therepresentative-agent economy.

References

Aiyagari, R.S., 1994. Uninsured idiosyncratic shock and aggregate saving. Quarterly Journal of Economics 109,

659–684.

Attanasio, O.P., Browning, M., 1995. Consumption over the life cycle and over the business cycle. American

Economic Review 85, 1118–1137.

Attanasio, O.P., Weber, G., 1989. Intertemporal substitution, risk aversion and the Euler equation for

consumption. The Economic Journal 99, 59–73.

16This calculation is based on the assumption that there is a utilitarian government which tries to attain the

same social welfare index as without taxes and makes transfers to agents in such a way to minimize the total

amount of transfers.

ARTICLE IN PRESSF. Guvenen / Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (2006) 1451–14721472

Attanasio, O.P., Banks, J., Tanner, S., 2002. Asset holding and consumption volatility. Journal of Political

Economy 110, 771–793.

Basak, S., Cuoco, D., 1998. An equilibrium model with restricted stock market participation. Review of Financial

Studies 11, 309–341.

Basu, S., Kimball, M., 2000. Long-run labor supply and the elasticity of the intertemporal substitution for

consumption. Working Paper, University of Michigan.

Blundell, R., Browning, M., Meghir, C., 1994. Consumer demand and the life-cycle allocation of household

expenditures. Review of Economic Studies 61, 57–80.

Browning, M., Crossley, T., 2000. Luxuries are easier to postpone: a proof. Journal of Political Economy 108,

1022–1026.

Browning, M., Hansen, L.P., Heckman, J., 1999. Micro data and general equilibrium models. in: Taylor, J.,

Woodford, M. (Eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics, vol. 1A. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Campbell, J.Y., Cochrane, J.H., 1999. By force of habit: a consumption based explanation of aggregate stock

market behavior. Journal of Political Economy 107, 205–251.

Campbell, J.Y., Mankiw, N.G., 1989. Consumption, income, and interest rates: reinterpreting the time series

evidence. NBER Macroeconomics Annual. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chamberlain, G., Wilson, C., 2000. Optimal intertemporal consumption under uncertainty. Review of Economics

Dynamics 3, 365–395.

Cooley, T., Prescott, E., 1995. Economic growth and business cycles. In: Cooley, T. (Ed.), Frontiers of Business

Cycle Research. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Epstein, L.G., Zin, S.E., 1989. Substitution, risk aversion, and the temporal behavior of consumption and asset

returns: a theoretical framework. Econometrica 57, 937–969.

Guvenen, F., 2004. A parsimonious macroeconomic model for asset pricing: habit formation and cross-sectional

heterogeneity? Working Paper, University of Rochester.

Hall, R.E., 1988. Intertemporal substitution in consumption. Journal of Political Economy 96, 339–357.

Hansen, L.P., Singleton, K.J., 1983. Stochastic consumption, risk aversion, and the temporal behavior of asset

returns. Journal of Political Economy 91, 249–265.

Investment Company Institute and the Securities Industry Association, 2002. Equity Ownership in America,

downloadable at hhttp://www.ici.org/pdf/i.

Jones, L.E., Manuelli, R., Stacchetti, E., 1999. Technology (and policy) shocks in models of endogenous growth.

Working Paper No. 7063, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jones, L.E., Manuelli, R., Siu, H., 2000. Growth and business cycles. Working Paper No. 7633, National Bureau

of Economic Research.

King, R.G., Rebelo, S.T., 1990. Public policy and economic growth: developing neoclassical implications. Journal

of Political Economy 98, S127–S150.

Krusell, P., Smith Jr., A.A., 1998. Income and wealth heterogeneity in the macroeconomy. Journal of Political

Economy 106, 867–896.

Laibson, D., Repetto, A., Tobacman, J., 1998. Self-control and saving for retirement. Brooking Papers on

Economic Activity, pp. 91–172.

Lucas Jr., R.E., 1990. Supply side economics: an analytical review. Oxford Economic Papers 42, 293–316.

Mankiw, G.N., Zeldes, S., 1991. The consumption of stockholders and non-stockholders. Journal of Financial

Economics 29, 97–112.

Ogaki, M., Reinhart, C., 1998. Measuring intertemporal substitution: the role of durable goods. Journal of

Political Economy 106, 1078–1098.

Poterba, J., Samwick, A.A., 1995. Stock ownership patterns, stock market fluctuations, and consumption.

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 295–373.

Summers, L.H., 1981. Tax policy, the rate of return, and savings. Manuscript No. 995, National Bureau of

Economic Research.

Vissing-Jørgensen, A., 1998. Limited asset market participation and the elasticity of intertemporal substitution,

Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Weil, P., 1989. The equity premium puzzle and the risk-free rate puzzle. Journal of Monetary Economics 24,

401–421.

Wolff, E., 2000. Recent trends in wealth ownership, 1983–1998. Levy Institute Working Paper, No. 300.