Four Visions of the Apocalypse Disintegration in the Early Work of J.G. Ballard

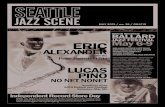

Rage Magazine (Mark Dery Interviews Crash Author j.g. Ballard

description

Transcript of Rage Magazine (Mark Dery Interviews Crash Author j.g. Ballard

GUARANTEEDIAII Girls NOW Silicon Free!

CHEMLAB

Ma-r,k D~ryInterviewsORliSHSJ.G. Ballard

fiction byPaulJ. McAuley

TROMFILMSStill ToxicAfter

All TheseYears

-Mark Dery: I wanted to begin

with an intriguingremark DavidCronenberg made to me in my recent inter-view with him: he said that during your recent publicdialogue with him at the Institute of Contemporary Art inLondon, the question of the moralistic tone you took in your intro-duction to the French edition of Crashcame up. ,'ve alwayswonderedabout that, because it seems out-of tune with the book itself,which is flatlyrepor-torial, appropriate to the flattened affect of the characters. Cronen berg said that you con-fessed to him that you appended that introduction after Crashwas written, and that you had somedoubts about how consonant it was with the bookJ.G. Ballard: The question you've asked is one which was asked by a member of the audience. David made it ~-_

quite clear that he didn't see the film as a cautionary tale, and I pointed out that at the time that I wrote Crash,roughly25 years ago, I certainly didn't see it as a cautionary tale. I was exploring certain trajectories that' saw movingacross the men-tal sky of the planet, followingthem to what seemed to be their likelymeeting point. Moral considerations were neither here northere; I saw myself in the position of a computer attached to a radar set, tracking an incomingmissile. In fact, most of the introduc-tion consists of an endorsement of the nonmoralistic view of Crash,in that I make the point that an author can no longer presidelike a magistrate over his characters and place their behavior within some sort of moral frame, which is the traditional stance of theauthor in fiction. Most criticism of the novel sees it as an instrument of moral criticism of life. I mean, that's the raison d'etre thatjustifiesthe teaching of Englishliterature at universities.MD: Well, American tabloid newscasts still follow that script. They always end with what amounts to a scriptural flourish, and

.there's a Manicheansense that good has triumphed over evilon the slaughter bench of the six o'clock news.GB: Absolutely; that's very well put. I think that's true over here, to a lar~e extent, but I think it's more true in the States, because

. k Americans are a very moralistic people for historical reasons we don t need to go into. Most of my Introduction disputes this

---- ---

view that thenovelist is a moral arbiter, and it's only inthe last paragraph that I actually say that Iregard Crashas a cautionary tale. WhichI do, inthe sensethat Crash,whateverelse it is, is a warning, and insofar as itissues a warning, it's a cautionary tale. Imean, a road sign saying,"Dangerousbends ahead; slow down," is not makingamoral statement, it's being cautionary. Inthat sense"Cd like to think that David'sfilmis a cautionary tale.

MD: In what regard?JGB: Well, I don't want to invoke

Swift's"A Modest Proposal," because it'sso easy to do, but it is possible to playdevil's advocate by deadpanning an atti-tude which seems to be 180 degrees atvariance with what one's supposed to bedoing.

MD: This often seems to be lost oncritics, especiallyof the moralistic stripe,who, if they have a common

trait, seem to exhibitan almost painfulearnestness thatvaporizes irony on contact.JGB: Absolutely.MD: And as a result there's a tenden-

cy, there, to take Crashliterally.JGB: You see, I think this ambiguityis

very important. People have constantlyasked me over the last year, (and theywere sayingit to me nearly 2S yearsago when Crashwas published), "Whatare you saying? Do you believe that weshould all be going out and crashing ourcars? You can't be serious!" But thatambiguityis part and parcel of thewhole thing. In Crash,I'mtaking certaintendencies which I see inscribed in theworld we live in and I'm followingthemto their point of contact. Putting itcrudely, I'm saying,"So you think vio-lence is sexy? Well, this is where itleads."

But ifyou say to me, "Do you thinkwe should allgo out and crash ourcars?," I would say, "Of course not!"This is a very important distinction.I've never said that car crashes are sex-

uallyexciting; I've been in a car

crash, and I can tell you it did not..-ingfor my libido! What I have said is thatthe ideo of car crashes is sexuallyexciting,which is very different and in a way muchmore disturbing: Why is it that our imagi-nations seem so fixated on this particularkind of accident?

MD: Crosh'snarrator,JamesBallard,says at one point that it took a car crashto snap him out of his terminal emotion-lessness: "For the first time I was in physi-cal confrontation with my own body," hesays. In Crash,the car crash functions asa bracing jolt that reconnects us with ourbodies-bodies that are part of a materialreality that seems to be receding as wespend more and more time on the otherside of the screen, be it the computerterminal, the television, or the videogame.JGB: Of course, it's the ideoof the car

crash which jerks us out of our apathy;this is the important thing. One mustn'ttake brief episodes from a novel and tryto generalize a complete moral universefrom them, because these are just cogs ina machine whose purpose is unknown tothe cog. I mean, the characters' roleswithinCrashhaveto be seen as fullyinte-grated into an imaginarydrama, and it'sthe drama as a whole that one shouldlook at.MD:RobertTowers, in hisNewYork

Reviewof Books review of The KindnessofWomen takes you to task for the "lack ofinwardness and psychologicaldepth" hesees in your writing. But I think he andothers like him miss the point that yourfiction constitutes arsychoanalysis ofthe postmodern sel . To my mind,

you're one of the first novelists to offera science-fiction premonition of the post-modern ego-a decentered self, to usethe cultural critic Frederick Jameson'sterm, disoriented by the generic place-lessness of mallsand retail chains and thevertiginous whirl of free-floating facts andimages peeled loose from their referents.Does this resonate with your thinking?JGB: Absolutely. For the last 30 years,

ever since I started writing the piecesthat made up The AtrocityExhibition,I'vebeen sayingthat we live in a world ofcomplete fiction; so much of what usedto be an internalized psychologicalspacewithin an individual'shead-his hopes,dreams, and all the rest of it-has beentransferred from inside our individualskulls into the corporate sensorium rep-resented by the media landscape. Yousee people, these days, who give theimpression that their minds are a com-plete vacuum; no dreams or hopes of anyimportance-even to themselves-emanate through the sutures of theirskulls, as it were. But that doesn't mat-ter, in a sense, because the environmentitself is doing the dreaming for them.The environment is the greater sensori-

um generating theseindividualhopes and ambitions, signs ofthe cerebral activity that has been trans-ferred from inside the individual'sskullinto the larger mental space of the plane-tary communications landscape.

Now that's a very dramatic shift,because it means that Freud's distinctionbetween the latent and manifest contentof a dream now has to be applied to theoutside world. You can't just say thatthese huge figments and fantasies thatfloat across the planet and constitute ourreal sky can be taken at face value; theycan't. .

Exactly30 years ago, when I wrote mypiece, 'Why I Want to Fuck RonaldReagan,"when Reaganwas governor ofCalifornia, I was trying to (Iwon't saydeconstruct, because that's a horribleword) analyzewhat Reagan really repre-sented. Part of the problem that somecritics have with the apparent lack ofdepth in my characters arises from thefact that my characters, right from theearliest days when I started writing fic-tion, were already these disenfranchisedhuman beings livingin worlds where thefictional elements constituted a kind ofexternalized mental activity. They didn'tneed great psychologicaldepth because itwas all out there, above their heads.

MD: You and Cronenberg seem toshare an interest in psychology in generaland Freud in specific;have you two dis-cussed psychology in relation to thecharacters in Crash?JGB: Not really. When Ifirst met

David, I'd seen all his films,but I think inmany ways we were so closely tuned toeach other that we really didn't need totalk about our respective work. Butthere are a surprising number of reso-nances between Cronen berg's work andmy own. I've always thought, from thebeginning,that he was the perfect choiceto film Crash. What's so interesting isthat Crashis in many ways unlike any ofhis other films. So many of theCronenbergian tropes, the biomorphichorrors and the pulsating washingmachines and so on, have all been aban-doned because they're not necessary any-more. The biomorphic horrors areimplicitwithin the ideas being portrayedin the most realistic way. Likewise,youknow, ifyou've got something as dramat-ic and contortionist as the car crash, youdon't need to play around with the every-day structures of material things.

MD: Watching the film, I was struck bythe extent to which its pathological sur-realism has come true. The whole idea

of the sexuali~ of scars is enacted now inthe so-called' modern primitive" subcul-ture, where those on the far fringes ofyouth culture have taken up scarificationas a fashion trend and a tribal totem.Crashseems lessand less like"an

extreme metaphorfor an extreme situation." as you call it inyour introduction. than a laboratory study ofan increasinglypathological culture.JGB: Well, at the ICA conversation in

London, I said to the audience that Crashillustrates what I call the normalizingofthepsychopathic-the way in which formerlyaberrant or psychopathic behavior isannexed into the area of the acceptable.This has been proceeding for probably acentury, ifnot longer, but certainly it hasgathered pace tremendously in the last 30or 40 years, and it's been aided by the pro-liferation of new communications technolo-gies: television, home videos, video games,and all the rest of that paraphernalia, whichallows the anatomizingof desire. The nor-malizingof the psychopathic is mostadvanced. o(course, in the area of sexuality.Sexual behavibr that my parents would havedeemed a one-way ticket to a criminalinsane asylum is now accepted in the priva-cy of the bedroom. tolerable ifboth partiesare in agreement. We're much Jessshocked than we used to be by deviantbehavior. I mean, the tolerance of malehomosexuality and lesbianismand the hugerange of what, previously, would have beenregarded as out-and-out forms of psy-chopathy are now accepted. And thisextends beyond sexuality, into otherrealms as well. To take a trivial example.among my parents' generation, shopliftingwas one of the most reprehensible thingsthe ordinary person could do, and ifyouwere arrested, it would lead to socialostracism. Nowadays, ifyour neighborwas arrested for shoplifting,one would besympathetic: "Poor woman, her husband'sbeen havingall these affairs,she's been veryunhappy..." We're extremely tolerant ofbehavior that would have outraged ourparents' generation.

MD: Again,in the introduction to Crash,you write that "the demise of feelingandemotion has paved the way for all ourmost real and tender pleasures...in theexcitements of pain and mutilation." InCrash,sex, although unencumbered by thetrappings of S&M,is characterized by a rit-ualized brutality that is undeniably sado-masochistic. What do you make of thestrip-mailingof S&M,in the basementscene inPulpFiction,in Madonna's Sex, inGianniVersace's bondage collection, inBatmanForever,and so on? S&Mseems tobe emergingas the talismanicsexuality ofmillennialculture.JGB: It's puzzling,because ifyou don't

share a particular sexual proclivity, it'srather difficultto get worked up about it.But I agree with you; it's everywhere-inmagazines.advertising, and the like. Andone wonders what the subtext really is;whether it's purely a sort of style. intro-ducing a bawdyfascism-the glamour ofthe jackboot, the thrill of the psychopath-ic and the forbidden-or whether it's akind of personal theater in which onesees a preview of pathological virtual real-ity fantasies. I don t know. It strikinglydramatizes all sorts of moral ambiguities;it's a willfulmimicry of activities that inany other space would be regarded asnear criminal.

MD: The Surrealists were great fans ofde Sade. and enshrined him as an hon-orary Surrealist. Didn't you. at one time,

immerseyourself in him?JGB: Immerse myself in de Sade?

What a thought! (laughs)MD:(laughing)Idon't mean

bodily, I mean mentally.JGB: Well. he was, in his

way, a genius; I oncedescribed The /20 Daysof Sodomas a "blackcathedral of abook." De Sadeis an enormouslyimportant influenceon us today, and hasbeen for a long while. Heconstructs a highlyconvincinganti-society which defies bourgeoissociety and liberalism by constructing acommunity based on torturers and their willingvictims. Now, that's a prospect that the liberalconscience just cannot cope with. I'd like to thinkthat Crashisa moviede Sadewouldhaveadored.

MD: You seem to enjoy nettling ideologues and moral cru-saders at both extremes of the political spectrum, and yet, inyour reviewof MauriceLever'sMarquisdeSade[includedinBallard'sA User'sGuideto The Millennium],you raise the moral flagy,ourself,noting that "the jury will always be out" on de Sade, whose'novels have been the pillow-books of too many serial killers for comfort."JGB: Well, that's a worry. isn't it? One can see, on one hand, that de Sade is

an enormously important figure in European and American thought. On the otherhand, he has been the pillow reading of too many psychopaths-the MoorsMurderers, Ian Bradyand Myra Hyndley,who killedchildren, for example.

MD: Likede Sade, they're practically pop stars now.JGB: Yes, and I'm not sure that's a good thing. either. One of the Surrealists-

Breton, I think-said that the ultimate Surrealist act would be to take a revolver andfire at random into a crowd. Now, one can salute the brilliance of that insight, but atthe same time ifsomebody actuallyfound a revolver and put that insight into prac-tice. one would have to deplore it. This same ambivalence,this ambiguity,is at theheart of something like Crash,and this is what people find difficultto cope with-thatthere's no clear moral compass bearing. I'llbe very interested to see how the filmisreceived in the States.MD: Throu~hout the novel. there is an almost "paranoiac-critical" confusion, to use

Salvador Dalis term, of bodies and the built environment. of flesh and commodityfetishes. There's an obsessive repetition of geometry. as in, "Myright arm held hershoulders, feelingthe impress of the contoured leather, the meeting points of hemi-spherical and rectilinear geometries." Disappointingly,we catch only fleetingglimrsesof this Euclideaneroticism in the movie. I kept lookingfor signature images like 'theconjunction of an air hostess's fawn gabardine skirt...and the distant fuselagesof theaircraft," but they weren't there.JGB: One or two people have pointed that out. But to be fair to Cronen berg, no

filmcan possibly contain the whole of a novel in a couple of hours. The importantthing is to concentrate on the nervous system of the novel. I think David has donethat; he'sgoneto the heart of the obsessionalworld that Crashdescribes.

I've seen the filmthree or four times, now, and I constantly see things in it that Ihadn't seen before. The performances are wonderful, and the film itself is very art-fullyconstructed. It's ostensibly quite naturalistic. but in fact it inhabits a strangepenumbral space. There's something deeply premonitory about it. deeply prophetic.Just as some films cast a light on the past. this one seems to cast a light into thefuture.

MD: I'd like to end with a few obvious questions. One of Cronenberg's earliestfeature filmswas a movie about cars, FastCompany,and the first movie he ever madewas an a-millimeter documentary about auto racing in which a CBC producer waskilledwhen his Triumph TR3 rolled over. Have you and he talked about cars?JGB: We talked about his Ferrari, and the differences between American indy car

racing and European Grand Prix racing, over dinner in Cannes. He's a great car buff,which I'm not. People think I'm a car fanatic, but in fact I'm not in the least interest-ed in cars, really. although I am interested in the psychologyof automobile design,car stylingas a barometer of the public imagination. Fluctuations in American auto-mobile design over the decades seem to reflect the state of the American psyche: theenormous Baroque and confidence of the Eisenhower years, and then, afterKennedy's death, the puritanical slab, flat-sided and undecorated-the American carwas in mourning. No, not in mourning-it was in denial, to use the latest jargon.But now it's started to get more exuberant, hasn't it?MD: There seems to be a rroliferation of post-Moderne compact cars-downsized

versions of Raymond Loewys aerodynamic roadsters of the '30s. How do you psy-choanalyze this neo-streamlining vogue? 78 ~JGB: I think it reflects an awareness of the future. Thirties design was

-----

Dstrongly influ-enced by the sensethat one would be liv-ing in the future, and Ithink people are get-ting more aware ofthe future as thecountdown to the year2000 comes. Maybethe human race is t'l-ing to escape. It can tgo into outer space,because that's basicallyinaccessible,and it'salready tried to escapeinto inner spacethrough drugs and mys-ticism and to someextent, the Internet.Maybe it's going to tryto escape into anotherrealm altogether. Godknows what it will be.MD: Your characters

are alwaystrying to tearloose from the time-space continuum. Iwonder if, in a weirdway, the car crash is anattempt to tear throughthe fabric of reality-to"break on through," asthe '60s catchphrase hasit.JGB: I think so,

absolutely. As I've oftensaid, we live in a world ofmanufactured goods thathave no individualidenti-ty, because every one islike every other one, untilsomething forlorn or trag-ic happens. One is con-stantly struck by the factthat some old refrigeratorglimpsed in a back alleyhasmuch more identity thanthe identical model sittingin our kitchen. And noth-ing is more poignant than afield fullof wrecked cars,because they've taken on aunique identity that theynever had in life.MD: One could imagine

the crash as the car's des-perate attempt to estab-lish-if only for a fleetingmoment-a sort of self-hood, even at the expenseof its existence.JGB: Exactly. Very

strange, that; paradoxical.Also, there is a deep melan-choly about fields fullof oldmachinery or wrecked carsbecause they seem to chal-lenge the assumptions of acivilizationbased on an all-potent technology. Thesemachine graveyards warn usthatnothingendures.MD: One last question:

what sort of car are you dri-ving now?JGB: Oh, this willshock you!

I drive a Ford

cR

IIIIIIII

1!

IiI:IIIIIIIIII

II _ ,- Jn.:rcrrr-.:1Hun

( 1131-&511-511011I1111II

H 7.0& )

I: man e y~-------------------------------

Granada.MD: Dear

Lord.JGB: Iknow. But

again, ('m not interest-ed in cars.MD: You had a

rollover right after com-pletingCrash;didthenovel in a sense impelthat? Was that the finalplot twist, an instanceof the book leaking intoreality?JGB: Well, had I died

in the crash, twoweeks after completingthe manuscript, peoplewould have said thatthis was a willed death,expressing the essenceof the book. (think itwas pure coincidence,actually, because Ifound writing thebook a very fearfulexperience. I hadthree very young chil-dren crossing theroad a hundred timesa day, and never atany point during writ-ing that book did Iever envisage puttingthat psychosis intopractice. I was toofrightened by what Iwas uncovering towant to test out thetheories the bookseemed to embody.So I certainly don'tthink I had ablowout because Iwanted to. I thinkit was a case ofnature imitating art.An extreme case. ..NEXT ISSUE:~ark Derv.lnt~d

rvlewsUavi

Cronen berg!

s h e I s

n I c e a n d

w I I I t a k e

y a u r

-----------------

Ii

I

IIIIIIIIIIII

I

she

n

w,I

I: you r :.I I'I I: m 0 n ey :~ ~

Dstrongly influ-enced by the sensethat one would be liv-ing in the future, and Ithink people are get-ting more aware ofthe future as thecountdown to the year2000 comes. Maybethe human race is t'('-ing to escape. It can tgo into outer space,because that's basicallyinaccessible,and it'salready tried to escapeinto inner spacethrough drugs and mys-ticism and to someextent, the Internet.Maybe it's going to tryto escape into anotherrealm altogether. Godknows what it will be.MD: Your characters

are alwaystrying to tearloose from the time-space continuum. Iwonder if, in a weirdway, the car crash is anattempt to tear throughthe fabric of reality-to"break on through," asthe '60s catchphrase hasit.JGB: I think so,

absolutely. As I've oftensaid, we live in a world ofmanufactured goods thathave no individualidenti-ty, because every one islike every other one, untilsomething forlorn or trag-ic happens. One is con-stantly struck by the factthat some old refrigeratorglimpsed in a back alleyhasmuch more identity thanthe identical model sittingin our kitchen. And noth-ing is more poignant than afield fullof wrecked cars,because they've taken on aunique identity that theynever had in life.MD: One could imagine

the crash as the car's des-perate attempt to estab-lish-if only for a fleetingmoment-a sort of self-hood, even at the expenseof its existence.JGB: Exactly. Very

strange, that; paradoxical.Also, there is a deep melan-choly about fields fullof oldmachinery or wrecked carsbecause they seem to chal-lenge the assumptions of acivilizationbased on an all-potent technology. Thesemachine graveyards warn usthat nothing endures.MD: One last question:

what sort of car are you dri-ving now?JGB: Oh, this willshock you!

I drive a Ford

cR....

RIII

II _ I,

in-'-CraT~e HUn

( 113.1151'510111II11II

H 7 !UJIi )s

c a de n

t k ea

Granada.MD: Dear

Lord.JGB: I know. But

again, ('m not interest-ed in cars.MD: You had a

rollover right after com-pletingCrash;didthenovel in a sense impelthat? Was that the finalplot twist, an instanceof the book leaking intoreality?JGB: Well, had I died

in the crash, twoweeks after completingthe manuscript, peoplewould have said thatthis was a willed death,expressing the essenceof the book. (think itwas pure coincidence,actually, because Ifound writing thebook a very fearfulexperience. I hadthree very young chil-dren crossing theroad a hundred timesa day, and never atany point during writ-ing that book did Iever envisage puttingthat psychosis intopractice. I was toofrightened by what Iwas uncovering towant to test out thetheories the bookseemed to embody.So I certainly don'tthink I had ablowout because Iwanted to. I thinkit was a case ofnature imitating art.An extreme case. ..

NEXT ISSUE:~ark Derv.lnt~!;VlewsUaVlu

Cronenberg!