Racial Microinsults in St. Olaf Classrooms · 2018-07-11 · International students are more likely...

Transcript of Racial Microinsults in St. Olaf Classrooms · 2018-07-11 · International students are more likely...

● People who scored high on one MA index (microinsults, microinvalidations, microassaults) were more likely to score high on the other two MA indices (p=0.000).

● Students of color are more likely to report observing or experiencing microinsults than white students. On our student-to-student microinsultmatrix, students of color reported almost twice as many microinsults as white students (p=0.003).

● International students are more likely to report observing or experiencing microinsults than domestic students (p=0.000 for student-to-student index, p=0.050 for professor-to-student index).

● Students with majors in natural science/ mathematics, fine arts, and humanities were more likely to observe or experience professor-to-student microinsults than students who did not have majors in those divisions (p=0.001, 0.021, 0.019, respectively).

● How often do racial microinsults occur?

● What types of racial microinsults occur?

● Who are the targets of racial microinsults?

ResearchQuestions

● Focus group use to construct survey questions● Sample: Survey sent to 2,844 St. Olaf students

(all students on campus and not enrolled in SOAN 371); 25.2% response rate (718/2844)

● Independent Variables: Race/Ethnicity; Gender; Major; International Student (yes/no)

● Dependent Variables:○ Frequency of microinsults (Index of Student-to-

Student Microinsults and Index of Professor-to-Student Microinsult)

○ Type of microinsults (Student-to-Student MIs Matrix and Professor-to-Student MIs Matrix)

○ Target/Observer vs. Not (Indexes and additional survey question)

Methods

● 59.9% of respondents have observed or experienced a student stating or implying a racial, ethnic, or national stereotype about a group of people at least once in the first 11 weeks of this semester.

● 35.5% of respondents reported observing a professor focusing uninvited attention on a student of color or international student at least once in the first 11 weeks of this semester.

● Female-identifying students were more likely than male-identifying students to report observing or experiencing microinsults perpetrated by both professors (p=0.000 for both indices).

Results:Part2

Boysen, Guy A. 2012. “Teacher and Student Perceptions of Microaggressions in College Classrooms.” College Teaching 60(3): 122-129.Collins, Patricia. H. 2004. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York: Routledge.Ford, Kristie A. 2011. “Race, Gender, and Bodily (Mis)Recognitions: Women of Color

Faculty Experiences with White Students in the College Classroom.” The Journal of Higher Education 82(4): 444-478.

García, Alyssa. 2005. “Counter Stories of Race and Gender: Situating Experiences of Latinas in the Academy.” Latino Studies 3(2): 261-273. Harper, Shaun R. 2013. "Am I My Brother’s Teacher? Black Undergraduates, Racial Socialization, and Peer Pedagogies in Predominantly White Post-Secondary

Contexts." Review of Research in Education 37.1: 183-211.Harwood, Stacy A., Shinwoo Choi, Moises Orozco, Margaret Browne Huntt and Ruby Mendenhall. 2015. “Racial Microaggressions at the University of Illinois at Urbana-

Champaign: Voices of students of color in the classroom.” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.Museus, Samuel D., and Julie J. Park. 2015. "The Continuing Significance of Racism in the Lives of Asian American College Students." Journal of College Student

Development 56(6): 551-569.Parker, W. Max, Ana Puig, Joseph Johnson, and Clarence Anthony, Jr. 2016. "Black Males

on White Campuses: Still Invisible Men?" College Student Affairs Journal 34(3): 76-92.Pittman, Chavella T. 2010. "Race and Gender Oppression in the Classroom: The Experiences of Women Faculty of Color with White Male Students." Teaching

Sociology 38(3):183-196 Suárez-Orozco, Carola, et al. 2015. "Toxic rain in class: Classroom interpersonal microaggressions." Educational Researcher 44(3): 151-160.Sue, Derald Wing, Christina M. Capodilupo, Gina C. Torino, Jennifer M. Bucceri, Aisha M.B. Holder, Kevin L. Nadal, and Marta Esquilin. 2007. “Racial Microaggressions

in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice.” American Psychologist 82(4):271-286.Yosso, Tara J., William A. Smith, Miguel Ceja and Daniel Solórzano G. 2009. "Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate for Latina/o

Undergraduates." Harvard Educational Review 79(4):659-690,781,785-786

References

Results:Part1

Racial Microinsults in St. Olaf ClassroomsEmma Beahler, Kellis Brandt, Michelle Olson, and Anna Perkins

SOAN 371B, Fall 2017, St. Olaf College, Northfield, MN

● Recommendation: Mandatory anti-racist training for students and professors on racialized microinsults and other microaggressions(environmental, microinvalidations, microassaults)

● Strengths: Fills a gap in literature (microinsults, MAs at liberal arts colleges), St. Olaf-specific

● Limitations: Self-report, data limited to this semester in classrooms only, positionality of research team (white, female)

● Future research: Investigate microinsults outside the classroom

Conclusion

● Microinsult (MI) = often unconscious, rude verbal or nonverbal acts that belittle someone’s racial identity (Sue et al. 2007)

● Student-to-Student MIs include: racial/ethnic stereotypes, white students staring at students of color, white students avoiding sitting next to a student of color (Harwood et al. 2015, Minikel-Lacocque 2013, Museus and Park 2015, Parker et al. 2016)

● Professor-to-Student MIs include: ascription of intelligence based on race/ethnicity, race/ethnicity stereotypes, minimization of oppression (Harwood et al. 2015, Suárez-Orozco et al. 2015)

LiteratureReview

● 72% of students reported having observed at least one student-to-student microinvalidation.

● White students were more likely to report never seeing any of the student-to-student microinvalidation indicators, compared to students of color.

● Students reported observing more student-to-student than professor-to-student microinvalidations. However 35% of respondents reported seeing at least one professor-to-student microinvalidation in an academic space in the first 11 weeks of the semester.

● Students of color had a higher mean (Mean=4.92) on our student-to-student microinvalidation index than white students (Mean=3.02). Students of color are more likely to observe (notice) or be the target of microinvalidations.

● Female students tended to score higher than male students on our microinvalidations index. This was reflected in our target/observer survey question where females were more likely to be targets and/or observers.

ResultsandDiscussion

Microinvalidations in St. Olaf Academic SpacesRachel Bongart and Juni Lie

● More recent studies have found that racism -long considered overt, explicit and intentional - has become more covert, implicit and unconscious (Minikel-Lacocque 2013).

● Students of color often feel their mere presence in the classroom is invalidated (Harwood 2015)

● Microinvalidations describe often-unconscious microaggressions that ignore, neutralize or negate the lived experiences and emotional realities of racially, ethnically and nationally underrepresented students, such as denying white privilege (Sue et al. 2007).

LiteratureReview

1. What type of “racialized microinvalidations” occur most often in St. Olaf academic spaces?

2. Do “racialized microinvalidations” occur in some academic spaces more than others?

3. What are the demographics of students who:a. are targeted by microinvalidations?b. observe microinvalidations?c. are neither targets nor observers?

ResearchQuestions

● Focus group used to inform our survey questions in the context of St. Olaf College

● Anonymous survey sent to 2,844 students at St. Olaf College. 718 responded (25.2% response rate)

● Survey questions on microinvalidations in academic spaces. Example indicators:○ Stated or implied “racism doesn’t exist

anymore”○ Stated or implied “I don’t see color”

ResearchMethodsHarwood, Stacy A., et al. 2015. "Racial

microaggressions at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Voices of students of color in the classroom."

Pierce, C. (1974). Psychiatric problems of the Black minority. In S. Arieti (Ed.), American handbook of psychiatry (pp. 512-523). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Sue, Derald W. and Madonna G. Constantine. 2007. "Racial Microaggressions as Instigators of Difficult Dialogues on Race: Implications for Student Affairs Educators and Students." College Student Affairs Journal 26(2):136-143

References● Training for professors: We recommend that the college provide

education and training on how professors can: ○ Recognize their personal biases○ Facilitate productive class discussions on microaggressions,

including working through tensions involved with (racially) difficult discussions and challenging stereotyping as it occurs

● Training for students: We also recommend that the college provide more in-depth, interactive training that:○ Explicitly addresses racism ○ Teaches them to recognize power dynamics and personal biases○ Provides them with specific language for discussing racism

Recommendations

Female Male

Target 11.1% 5.4%

Observer (not also target) 33.6% 20.1%

Neither 53.3% 74.5%

Students of Color White Students

Target 29.9% 2.2%

Observer (not also target) 17.3% 35.6%

Neither 52.8% 62.3%

Table 1: Target/Observer and Gender (Grouped) Bivariate Analysis

Table 2: Target/Observer and Race/Ethnicity (Grouped) Bivariate Analysis

What kinds of microassaults happen in St. Olaf classrooms? Who commits and who notices these microassaults?

ResearchQuestions● Professor mocking language styles or

imitating accents: 10.3% of respondents indicated experiencing or observing this at least once this semester

● Professor telling a joke that mocked or degraded a R/E or nationality group(s): 8.7% experienced or observed this.

● These results are surprising, as the literature notes that overt forms of racism have become less common. Also note the difference in reported frequencies of student-perpetrated and professor-perpetrated microassaults.

● Students of color were more likely to report experiencing or observing these microassaults:

• Professor telling a joke that mocked or degraded a student’s race/ethnicity or nationality group (13.2% vs. 7.0%). This was statistically significant (Cramer’s V=0.091, p=0.026).

• Professor using a racial slur to address/refer to a person of color (5.4% vs. 1.7%). This was statistically significant (Cramer’s V=0.098, p=0.017).

ResultsandDiscussion(cont.)

NotSoMicro:MicroassaultsinSt.OlafClassrooms

PearlMcAndrews,MeghanTodd,andArleighTruesdale

We conducted a focus group to develop our survey questions. We administered an online anonymous survey to students at St. Olaf that yielded a 25.2% response rate (718/2844).

Main variables:● Self-identified Race/Ethnicity of the respondent

(Nominal)● Experience or observation of microassaults in

St. Olaf classrooms (Student and Professor Microassault Index)

ResearchMethods

Recommendations: ● Provide training for students and professors

that focuses on racism and microaggressions● Campus policy: Create and promote an

explicit policy regarding acts of racismStrengths: High response rate; generalizability Limitations: All white, female research team;

limited time Future Research: Examine all forms racism

both inside and outside the classroom

● Microassaults are often conscious, small-scale verbal or behavior attacks meant to harm the target with demeaning and degrading actions or words.

Sue et al. 2007: 274, Minikel-Lacocque 2013: 454

● Examples:○ Mocking language styles or imitating accents○ Telling jokes that mock or degrade a

racial/ethnic (R/E) or nationality group(s)○ Using a racial slur to address or refer to

person of color ○ Displaying racist symbols, such as a

confederate flag, swastika, or racist t-shirt

LiteratureReview

Minikel-Lacocque,J.2013.“Racism,College,andthePowerofWords:RacialMicroaggressionsReconsidered.”AmericanEducationalResearchJournal, 50(3):432-465.

Sue,DeraldWing,ChristinaM.Capodilupo,GinaC.Torino,JenniferM.Bucceri,AishaM.B.Holder,KevinL.Nadal,andMartaEsquilin.2007.“RacialMicroaggressionsinEverydayLife:ImplicationsforClinicalPractice.” AmericanPsychologist82(4):271-286.

References

Conclusion

● Student(s) mocking language styles or imitating accents: 42.8% of respondents indicated they experienced or observed this in class at least once this semester in class (first 11 weeks)

● Student(s) telling a joke that mocked or degraded a R/E group(s) or a nationality group(s): 39.7% experienced/observed this.

● These results are surprising: the literature indicates that overt forms of racism have become less common.

● Students of color were twice as likely as white students to report experiencing or observing a student using a racial slur to address or refer to a person of color (21.9% vs. 10.0%). This was statistically significant (Cramer’s V=0.147, p=0.000).

● This fits with prior research; students of color may notice/report more racial microassaults because of being targeted by them.

ResultsandDiscussion

In which types of classes are microaggressionsmost likely to occur at St. Olaf (e.g. lecture-based vs. discussion-based, STEM vs. Humanities, etc.)?

ResearchQuestion ResultsandDiscussion

NotSoMicro:EnvironmentalMicroaggressionsinSt.OlafClassrooms

PearlMcAndrews,MeghanTodd,andArleighTruesdale

Weconducted afocusgrouptodevelopoursurveyquestions.WeadministeredtheonlineanonymoussurveytostudentsatSt.Olafandyieldeda25.2%responserate(718/2844).Ourmainvariableswere:● Self-identifiedRace/Ethnicityoftherespondent(Nominal)

● SettingofexperiencedorobservedMAs(SettingIndex)

● FrequencyofstudentsreportingdepartmentswithmostandleastMAs

ResearchMethods

Harwood,StacyA.,etal.2015."RacialmicroaggressionsattheUniversityofIllinoisatjjjjjjjjUrbana-Champaign:Voicesofstudentsofcolor intheclassroom."Minikel-Lacocque,J.2013.“Racism,College,andthePowerofWords:RacialMicroaggressions

Reconsidered.”AmericanEducationalResearchJournal, 50(3):432-465.

Recommendations: ● Increase funding and specific resources to

support students and faculty of color● Provide training for all professors to discuss

MAs and mitigate effects and prevalenceStrengths: High response rate; statistical jjjjgeneralizability Limitations: All white, female research team; jjjjlimited timeFuture Research: Examination of forms of jjjjinstitutional racism

● Environmental microaggressions are incidents or situations on a systemic level, differentiating them from the other three categories of MAs; they are macroscopic manifestations of racialized assaults, insults, and invalidations Minikel-Lacocque 2013: 436

○Ex:excluding academic material that focuses on the narratives of people of color, failing to create a welcoming and supportive learning environment, and insufficient resources forstudents of color

● Overall, microaggressions (MAs) occur at differing incidence rates depending upon the setting (i.e. more at night, in social spaces with drugs/alcohol)

● We are filling a gap in the literature about MAs as they occur in undergraduate classrooms and academic settings. Harwood et. al 2015: 5

LiteratureReview

References

Conclusion

Figure 1 (Cramer's V=0.128, p=0.018 p<.05) Figure 2 (Cramer's V=0.066, p=0.344, p>.05).

Figure 3 Figure 4

● 37.3% of respondents reported having experienced or observed a MA during a class discussion; 29.7% during group work with other students; 25.4% during a lecture; and 17.7%during a music ensemble led by faculty during the first 11 weeks of fall semester.

● 19.2% of respondents reported having experienced or observed a professor including course material that depicted racism but did not discuss the material as racist in a class during fall semester.

● Students of color were more likely to report a discussion of racism focusing on the experiences or perspectives of white students rather than of students of color in classes than white students; this was found a significant interaction (Cramer's V=0.128, p=0.018 p<.05). Figures 1 and 2

● Students identified the departments in which they believe the most/least MAs occur (not limited to this semester Fall 2017). Note that some departments are listed in both tables. Figures 3 and 4

LiteratureReview ResearchQuestions Results/DiscussionPart2

ImmediateandShort-termReactionstoRacializedMicroaggressionsintheCollegeClassroomFrankDelaney,GraceJackson,andClaireMumford

§ School-wide survey (2844 invited), 25.2% response rate (718 Responses)

§ 5 Survey Questions§ Variables:§ Positionality (Target, Observer, Target and

Observer, Neither; Race; Class year)§ 15 response categories, such as “reacted

nonverbally,” “stayed silent,” etc. § Open-ended option§ Most effective and least effective responses to

microaggressions

Methodology

Boysen, Guy A. (2012). “Teacher and Student Perceptions of Microaggressions in College Classrooms.” College Teaching. 60:3, 122-129.Ford, Kristie A. (2011). “Race, Gender, and Bodily (Mis)Recognitions: Women of Color Faculty Experiences with White Students in the College Classroom.” 82:4, 444-478.Harper, Shaun R. (2013). “Am I brother’s teacher? Black undergraduates, racial and peer pedagogies in predominantly white postsecondary contexts.” Review in Education. 37: 183-211.Salazar, C. F. (2009). “Strategies to survive and thrive in academia: The collective voices of counseling faculty of color.” International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 31:4, 181-198.Solarzano, Daniel, et al. (2000). “Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate: The Experiences of African American College Students.” The Journal of Negro Education 69:60-73.

References

Results/DiscussionPart1

Conclusion

§ Microaggressions (MAs) are “characterized by ambiguity” and therefore often go unaddressed on college campuses (Ford 2011, Boysen 2012).

§ Microaggressions warrant a response, and professors and students respond to microaggressions in a myriad of ways (Harper 2013, Salazar 2009, Solorzano 2000).

§ Students cope with MAs by turning to academic student organizations to find solidarity with other students of color (Boysen 2012, Solaranzo 2000).

§ In the classroom, the most important variable is who is targeted—a student or a faculty member (Boysen 2012, Ford 2011, Harper 2013, Salazar 2009, Solorzano 2000).

§ How do students respond to microaggressions?§ Do responses differ based on positionality?§ How do professors respond to microaggressions?§ Which responses do students view as most and

least effective? How do these views compare with how students and professors actually respond?

Conclusion: § Students of color are disproportionately

targeted by racial microaggressions§ Student reports of their responses to MAs do

differ from what they view as most effective

Strengths:§ Appropriate sample size§ Direct response to relevant campus climate

Limitations:§ Positionality of white researchers§ Limited time frame to conduct research

Recommendations:§ Provide in-depth training for faculty, staff and

students to recognize and respond to MAs in the classroom

§ Provide clear/effective forms of official reporting, as the Community Incident Bias form is not utilized fully nor seen as very effective

§ MA Targets: Of the students of color respondents, 38 (29.9%) report they were the target of a racial/ethnic microaggression in the classroom during the first 11 weeks of this semester.

§ MA Targets and Observers: Of all respondents answering this question, 227 (38.4%) said they observed and/or were targeted by a racial MA in the classroom this semester

§ Most common student response to racial MAs: Nonverbal (64.7%)

§ Least common student responses to racial MAs: Reporting to faculty/staff/administration (2.9%) and using the Community Bias Incident form (0.7%)

§ Most common professor responses to MAs: ignoring, staying silent, or changing the subject when a MA occurred (36.1%).

§ Most effective way to respond to MAs (student view): Confront the enactor gently/asking questions (62.3%)

§ Least effective ways to respond to MAs: Confront the enactor forcefully/yelling (49.6%) and to stay silent/ignore the MA (48.5%)

● Racialized microaggressions can cause physical avoidance and emotional withdrawal, inflicting “racial battle fatigue” on students of color (Smith et al. 2007)

● Students may disengage from or drop a class which perpetuates MAs (Harwood 2015)

● Students of color in predominantly white classrooms often feel scrutinized and stereotyped (Harwood 2015, Harper 2013)

● Assumptions of racialized intelligence raise additional barriers to academic success for students of color (Minikel-Lacoqcue 2013)

Literature Review Results

“He didn’t really say that, right?”: The Impacts of Racial Microaggressions in Learning Environments

Manuel Cardoza, Isabel Galic and Rita Thorsen

● How do MAs impact students’ psycho-emotional well-being?

● How do MAs impact classroom social dynamics?

● How do MAs impact student learning outcomes?

Questions

● Focus group informed survey items● Of 2,844 invited, 718 responded for a 25.25%

response rate● Sample is roughly representative of school● 65.6% respondents identified as White

MethodsHarper, S. R. 2013. “Am I My Brothers Teacher? Black Undergraduates,

Racial Socialization, and Peer Pedagogies in Predominantly White Postsecondary Contexts.” Review of Research in Education 37(1):183–211.

Harwood, S. A., Choi, S., Orozco, M., Browne Huntt, M., & Mendenhall, R. (2015). Racial microaggressions at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Voices of students of color in the classroom. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Minikel-Lacocque, Julie. 2013. “Racism, College, and the Power of Words: Racial Microaggressions Reconsidered.” American Educational Research Journal 50(3):432–65

Smith, William A., Allen, Walter R., Danley, & Lynette L. (2007). “Assume the Position… You Fit the Description: Psychosocial Experiences and Racial Battle Fatigue Among African American Male College Students 51(4): 551-578.

References● Validate that MAs are real and harmful● Establish guidelines and strategies for

classrooms to commit addressing MAs● Educate professors to reduce MAs they

commit and address curricular and student to student MAs

● Address harms to psycho-emotional and academic well-being by expanding relevant services and lowering barriers to access

Recommendations

● 64.2% of all respondents reported negative social impacts

● 65.4% of targets and observers report negative academic impacts

● White students and students of color did not show a significant difference in impacts

86.5% students reported being negatively impacted in some way

Social Impacts: Academic Impacts:

● 73.2% of students report MAs causing negative psycho-emotional impacts

● Mean score students of color: 6.63● Mean score white students: 7.81● Score indicating no change: 9

(p<.05)

Psycho-emotional Impacts:

● Race-related materials in the classroom: Students should be exposed to and engage with these to make them conscious of issues surrounding racism and process their own experiences and biases (Dhillon et al. 2015)

● Discussions of racism reduce its presence and impacts on college campuses (Minikel-Lacocque 2013)

● Educating professors: They need education about microaggressions (MAs) and racism (Patterson-Rivera 2014) and help developing tools to engage with and prevent MAs in the classroom (Harwood 2015)

● Being proactive: There is a gap in the existing literature regarding how professors and institutions can proactively prevent MAs in classrooms and limit their impacts

LiteratureReview1. What proactive actions do professors take in classrooms to

limit or prevent racial MAs, how frequently do they occur, and how do students perceive their effectiveness?

2. How effective have initiatives outside of the classroom, such as Sustained Dialogue and DiversityEdu, been in limiting or preventing racial MAs inside the classroom?

ResearchQuestions1. Effectiveness: Overall, students view actions

taken by professors inside the classroom as more effective in limiting and preventing MAs in the classroom than actions taken outside the classroom. The majority also perceives outside-the-classroom proactive responses to be at least somewhat effective, except for DiversityEduTraining and its Follow-Up Dialogues, which the majority find “not at all effective”

2. Professor (in)actions: A majority of respondents report not experiencing a professor using the term MA (53.4%) and not experiencing a professor initiating a discussion on how to respond to MAs (66.7%) in their courses this semester, at least not by week 12

3. Infrequency of discussing/using the term MA: While there departments vary, it appears that no department does these things frequently

4. Discussions of racism: Of the professor-initiated proactive actions, students view these as “highly effective,” but the discussions more often focus on class materials and less often connect to campus or societal events

ResultsandDiscussion

Reducing Racism: Proactive Measures to Mitigate Racialized Microaggressions in College Classrooms

Maddy Chiu, Olive Dwan, Khadijah Gowdy, and Ann Jensen

● Focus groups: We conducted focus groups to inform the development of an anonymous online survey sent to all St. Olaf students on campus (excluding us) during fall semester

● Sample: We received a 25.2% response rate (718/2844), with sample representation generally consistent with that of the invited student sample, with the exception of a five percent higher response rate of students of color (21.5%, 129/718)

● Main Variables: ○ Individual and indexed frequency of

professors’ actions to proactively address racial MAs in the classroom

○ Students’ perceived effectiveness of the same professorial actions

○ Effectiveness of institutional or organizational measures outside of the classroom

ResearchMethods

Dhillon, Manpreet, et al. 2015. "Achieving Consciousness and Transformation in the Classroom: Race, Gender, Sexual Orientations and Social Justice." Sociology Mind 5.02: 74.

Harwood, Stacy A., et al. 2015. "Racial microaggressions at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Voices of students of color in the classroom."

Minikel-Lacocque, Julie. 2013. "Racism, college, and the power of words: Racial microaggressions reconsidered." American Educational Research Journal 50.3: 432-465.

Patterson-Rivera, Mirtha Rocio. 2014. “Student perceptions of multicultural competence in the graduate programs in the school of education at a small private college in the midwest.” Edgewood College Doctor of Education Degree Program: 1-150.

References

Recommendations: ● Increase professor-initiated proactive responses,

particularly discussions of racism● Create an in-person course that addresses

racism and MAs, and better integrate this information into curriculum across campus

Limitations: Small sample size, our positionality as students who experience and enact racial MAsStrengths: Informs gap in existing literature, relevant to campus current issues and STOGoalsFuture research: Focus on student-initiated proactive actions, improving the effectiveness and frequency of proactive measures, and the implications of racial MAs on “safe classrooms”

Conclusion

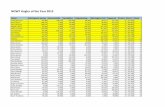

Professor Actions to Proactively Address Racial MAs in the Classroom

Not at all effective

Moderately Effective

Highly Effective

Discussing guidelines for how to address racism in class, such as expectations for classroom conduct regarding racism, how to respond to racist questions and comments, etc. (644 respondents)

10.4% 52.8% 36.8%

Initiating discussion of racism regarding class materials, such as in readings, film, plays, or music (657 respondents)

6.7% 40.9% 52.4%

Using the term microaggression, as related to the course and its material (641 respondents) 17.3% 52.4% 30.3%

Initiating discussion of microaggressions in the classroom, such as what they are and how to respond to them (641 respondents)

15.9% 46.0% 38.1%

Initiating discussion of racism in response to campus events and/or societal events such as elections and public protests (650 respondents)

9.4% 37.8% 52.8%

• Ladson-Billings (1995) defines transformative pedagogy as “culturally relevant pedagogy” (CRP), and describes it as education that promotes collective empowerment and critical understanding of social inequalities and oppressions. CRP promotes direct action and advocacy as an extension of learning.

• The implementation of CRP in schools demands structural, institutional changes to prepare teachers to use it (Young 2015).

• Scholars also conceptualize transformative pedagogy as social-psychological, through students’ tendencies to make structural vs. individualistic attributions when interpreting social phenomena (Lopez 1998).

LiteratureReview

• 33% of students reported that “None or Almost None” of course content in their majors, concentrations, and conversation programs included voices from racially/ethnically marginalized groups.

• Compared to standards of transformative pedagogy that emphasize the importance of including voices and perspectives from racially/ethnically marginalized groups (Nagdaet al. 2003), this is concerning and hinders students’ ability to fulfill the “Responsible Engagement” STOGoal.

• For each indicator measuring STOGoaloutcomes, approximately 20% of students reported that their major provided no support for them in achieving these goals.

• Literature views transformative pedagogy as key for developing cognitive-interpretive recognition of racial social structures and to action-based will to challenge such structures through direct action. These standards are mirrored by the Responsible Engagement STOGoal, which calls students to “Recognize and confront injustice and oppression.”

ResultsandDiscussionPt.1

TheRoleofCurriculainChallengingRacismatSt.OlafTimBergeland,KatieOpperman,SarahZhang

Recommendations:1. Evaluate GEs to ensure that all students

experience curricula which teaches an understanding of racism systematically.

2. Modify departmental review processes to ensure that each major discusses its relation to racial injustice, fulfilling the “Responsible Engagement” STOGoal.

3. Increase awareness of STOGoals so students understand intended outcomes and measure themselves to these standards.

Limitations: representation of departments, concentrations. conversation programs varies

Conclusion

Ladson-Billings,Gloria.1995.“ButThat'sJustGoodTeaching!TheCaseforCulturallyRelevantPedagogy.”TheoryintoPractice 34:3:159-165.Abingdon,UK:Taylor&FrancisPublishing.

Lopez,Gretchen.E.,Gurin,Patricia,andNagda,Biren.A.1998.“EducationandUnderstandingStructuralCausesforGroupInequalities”.PoliticalPsychology 19.2:305-329.

Nagda,Biren A.,PatriciaGurin,andGretchenE.Lopez.2003.“TransformativePedagogyforDemocracyandSocialJustice.”RaceEthnicityandEducation 6.2:Abingdon,UK:CarfaxPublishing.

Young,Evelyn.2010.“ChallengestoConceptualizingandActualizingCulturallyRelevantPedagogy:HowViableistheTheoryinClassroomPractice?”JournalofTeacherEducation 61.3:248-260.ThousandOaks,CA:SagePublications.

References

• Conducted a focus group on racism in the classroom to help generated survey questions

• Survey: Anonymous online survey sent to 2,844 students; received 718 responses (25.2% response rate).

• Independent variables: racial/ethnic identities, class year, and choices of majors, concentrations, and conversation programs.

• Dependent variables: extent of student-reported inclusion of voices from racially/ethnically marginalized groups, extent of student-reported fulfillment of STOGoals-based outcomes through their majors.

ResearchMethods

ResearchQuestions• Students with NSM majors tend to report

lower “Responsible Engagement” STOGoalfulfillment than those without NSM majors, while those with SS, HUM, and FA majors tend to report a higher fulfillment. The data show a link between the academic division of a student’s major and student tendencies to report STOGoal fulfillment via their major. Certain divisions may benefit from critical conversations regarding how to better link course content to the STOGoal of “Responsible Engagement.”

ResultsandDiscussionPt.21.To what extent do students report that

racially/ethnically marginalized voices are included within material in their majors, concentrations, and conversation programs?

2.Based on their experiences, which academic departments, concentrations, & conversation programs do students view as most effective in including voices and perspectives from racially/ethnically marginalized groups?

3.To what extent do students report their major as supporting them in starting or continuing to fulfill STOGoals?

Prior scholarship emphasizes these concepts:• Eurocentric Curricula: A Western-focused

education, giving preference to white scholars and their writings, and omitting or ignoring diverse socio-historical perspectives.

• Racist Pedagogy: Examples of racist pedagogy are excluding scholars of color from syllabi (Delpit 1988), including scholars of color in tokenizing ways (Fishman and McCarthy 2006), affirming color blind rhetoric in the classroom (Harper 2012).

• Positionality in the Classroom: Failure to address one’s positionality can lead to the perpetuation of institutional racism and negative pedagogical practices.

• Searching for Similar Faces: A sense of belonging is the state in which one feels “valued, needed, and considered important by other people or groups,” playing into students’ academic success (Costen 2012).

LITERATURE• 9.6% (53) of respondents “never” actively

participate in discussions of race and racism. • 26.2% (28) of students of color feel expected

to participate in “all or almost all” discussions of race/racism. Nearly 20% of respondents report feeling shut down from participating in at least “some” of these discussions.

• 10% of students “didn’t or didn’t want to register for a class” 5 times or more because the professor was not equipped to address issues of race and racism.

• Our data reveal that St. Olaf College is not currently fulfilling its mission to be an “inclusive community.” To do so, the college needs to create a learning environment in which all students feel respected and engaged in discussions of race and racism.

• A large portion of respondents reported that racism in the classroom did not affect their academic choices or their learning, but students of color disproportionately reported that classroom racism did affect their choices and learning.

RESULTSANDDISCUSSION

1. Hire more faculty of color to match the growing number of students of color.

2. Ask professors to use anonymous feedback forms to address issues in class during the semester.

3. Establish a required first-year seminar course for students to engage with issues of identity, specifically race/ethnicity.

4. The institution as a whole should redefine what diversity means to the college and how it is used in the college’s policies, programs, and promotional materials.

RECOMMENDATIONS

RacismintheClassroomanditsEffectsonStudentAcademicChoicesJennaCastillo,ChaseKoob,AbbyOlson,MariaJacquelynQuispe

• Main variables: the inclusion or exclusion of scholars of color in syllabi, participation in discussions of race, and the ways in which race and racism influence students’ academic choices

• Anonymous online survey sent to 2,844 St. Olaf students with 718 respondents, yielding a 25.25% response rate

• Of the 718 total respondents, 600 fit into the student of color/white student binary, with 78.5% (471) identifying as white and 21.5% (129) identifying as students of color

METHODS

WORKSCITED

1. In students’ views, to what extent and in what ways does the curriculum include and/or exclude racially diverse voices and perspectives?

2. To what extent and in what ways does the presence or absence of racially diverse voices and perspectives affect students’ academic choices?

3. Which students participate in discussions of racially diverse works or issues of racism within the classroom?

4. To what extent are racially diverse perspectives integrated in the curriculum versus tokenized?

RESEARCHQUESTIONS

Costen, Wanda M, et al. 2012. “Mitigating Race: Understanding the Role of Social Connectedness and Sense of Belonging in African–American Student Retention in Hospitality Programs.” Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education12(1):15-24.Delpit, Lisa D.. 1988. “The Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People’s Children.” Harvard Educational Review 58(3):280-298.Fishman, Stephen M. and Lucille Mccarthy. 2006. “Talk about race: when student stories and multicultural curricula are not enough.” Race Ethnicity and Education 8(4):347–64.Harper, Shaun R.. 2012. “Race without Racism: How Higher Education Researchers Minimize Racist Institutional Norms.” The Review of Higher Education 36(1):9-29.

We calculated a chi-square test of independence comparing the frequency of the decision to not register or not want to register for a class because the professor was not equipped to address microaggressions for students of color and white students, and found a significant interaction (X2 (3)=22.30, p>.05).

Decision to not register or not want to register for a class because you believe the professor is not

adequately equipped to address microaggressionsStudents of Color White Students

Never 71.1% 81.1%

1-2 times 17.2% 11.9%

3-4 times 3.9% 3.2%

5 times or more 7.8% 1.1%