Rabb PCB Stories

-

Upload

william-rabb -

Category

Documents

-

view

36 -

download

0

Transcript of Rabb PCB Stories

October 2014

Court won’t rule out cleanup of PCBs in bayby WILLIAM RABB

Note: PensacolaToday.com is the Studer Institute’s online daily newspaper. This story was Rabb’s idea. After more than six years of court �lings, he knew that the case could hold valuable new studies about PCBs in the bay. He spent weeks going through 37 volumes of court �les, reading studies and talking with experts.

Some 45 years after Monsanto Co. allowed some of the world's most dangerous and persistent chemicals to �ow into Escambia Bay, a Pensacola judge has ruled that a massive cleanup of the bay and river is not o� the table. The recent ruling by Escambia County Circuit Judge Jan Shackelford is the latest development in a lawsuit that began in 2008. If the plainti�s prevail, a cleanup could ultimately result in a remediation process that could cost more than $400 million – perhaps something like the years-long e�ort now under way on the Hudson River in New York State, where General Electric Co. dumped the same types of PCB compounds decades ago. The lawsuit was �led by 160 homeowners and businesses around Escambia Bay, who contend that Monsanto and its successor companies damaged their use of the bay and contaminated seafood with the PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, which have been classed as probable human carcinogens. The lawsuit, now in its 37th volume of �lings, has produced a raft of new studies and expert analyses that paint a grim picture of how the companies and regulators may have failed to properly deal with PCB leaks and runo� over the past half-century. Plainti�s' experts contend: The hazardous compounds are still seeping from the plant site in Gonzalez. The plant allowed PCBs to drain into nearby waterways, constituting an unpermitted discharge, in violation of state law. Recent soil and sediment samplings show high levels of the compounds on the plant site, in the river and the bay. Monsanto hid information from regulators and failed to take measures that would have prevented widespread contami-nation. The PCBs threaten dolphins and cormorants because levels in some hot spots are 780 times higher than federal protection limits. PCBs in bay oysters declined from 1989 to 1994, but have remained steady since then – suggesting contaminants are still entering the bay. State and federal authorities have done little to address the contamination, despite guidelines that call for concern.

The defendant companies have denied any wrongdo-ing, and said they have worked closely with regulators to prevent discharges of the chemicals to the river and bay. “The property owners who brought this lawsuit do not have PCBs from the plant on their properties, in their homes, or in the sediments adjacent to their properties,” reads a statement from Pensacola attorney Steve Bolton, who represents the defendant companies. “They, as can the entire Escambia Bay, Pensacola, and Milton communities, safely enjoy the wide range of bene�ts the bay provides.”

The companies declined to talk about the speci�cs of the litigation, but said a cleanup of the bay would be “unneces-sary, given the absence of any health risk posed by the ultra-low concentrations in the Bay,” Bolton said. Defendants Monsanto, its successor companies Solutia Inc. and Pharmacia Inc. and the new plant owner, Ascend Performance Materials, early on o�ered a $1,000 settlement for each plainti�, which most of them rejected. The case, known as John Allen et al vs. Monsanto et al, may go to trial early next year. Both sides have asked for a jury. Since initial news reports when the suit was �led, though, the health threats highlighted by the case have been all but forgotten by the public and by state health authorities. Bayside residents and scientists say that state and local agencies have done little to warn seafood lovers or to address the toxic sites. Some locals have taken it upon themselves to spread the word. “Don't eat the mullet, and don't eat the crab unless you take the fatty tissue out �rst,” plainti� Sherry Starling, a former state environmental inspector, said recently at a public gather-ing of concerned citizens.

The long arm of PCBs

Polychlorinated biphenyls, produced by combining chlorine and benzene, were once hailed as miracle compounds by industry because they can withstand extreme heat while retaining their lubricating and insulating properties in electrical and other equipment. Although most are oily compounds, they are heavier than water and sink into sediment. By the 1970s, PCBs had been shown to cause cancer and other health problems, kill marine life and damage bird eggs the world over. They were mostly banned by Congress in 1977, but some PCBs break down so slowly that they could be toxic in sediment for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years, studies show. Monsanto, a global company that started more than 100 years ago and was the sole U.S. manufacturer of PCBs, has acknowledged that PCBs were used at its nylon plant on the Escambia River, eight miles north of Pensacola, and that they

leaked from air compressors in late 1960s. Documents show the plant allowed as much as three gallons a day to drain into ditches that led to the river. The defendant companies have said that any seepage from the site today is “de minimus,” and contaminated areas in the bay are at concentrations below levels of concern. Defense experts have also said that plainti�s' studies have misinterpreted sediment data, and suggest that PCBs on the bay �oor could also have come from Gulf Power's Plant Crist generating station on the river, and from the former Air Products and Chemicals plant in Pace, which has a treated-waste discharge on the east side of the bay. Those companies strongly refute that suggestion, saying that they have no evidence that PCBs were ever used in quantity or spilled at their plant sites. The plainti�s are asking for monetary damages, but also that the defendants be required to pay for remediation of the contaminated areas around the plant site, in the riverbed and on the �oor of Escambia Bay, where mullet, crab and other marine life live and feed. The defendants this summer asked the judge to dismiss that part of the lawsuit, arguing that remedia-

tion would cost far more than any damages the plainti�s may have su�ered. After weeks of deliberation, Shackelford denied the request, and agreed with the plainti�s that before remediation could be ordered, a thorough site plan of the bay and contami-nated lands would have to be done, a step that itself could cost between $2.6 million and $5.1 million, according to expert witnesses the judge relied on. “The ecological threats...from exposures to PCBs in Escambia Bay will persist until the sources of PCBs, including the Monsanto site, and the environmental media are remediated,” wrote plainti�s' expert Jerome Cura, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Group in Massachusetts. Because PCBs build up in the food chain, even tiny amounts in sediment can end up being hazardous to wildlife and humans, experts said. Some of the studies have shown hot spots as high as 118 parts per billion (ppb) in bay sediment and 3,690 parts ppb in the river sediment. Florida sediment guidelines set 22 ppb as a “possible e�ects level” and

189 ppb as a “probable e�ects level” for biological damage. But Carl Mohrherr, a retired UWF biologist, and others said those state thresholds are misleadingly high: They only refer to immediate e�ects on organisms, and do not re�ect how the poison can bioaccumulate to more dangerous levels. Some plainti�s' experts suggested there's no safe level for the hardy compounds, and that Monsanto should have taken more precautions.“Monsanto documents show that the company had both the knowledge and technology available to prevent PCBs from being discharged into Eagle's Nest Creek and the Escambia River,” another plainti�s' witness, professor Jack Matson of Pennsylvania State University, reported. Most expert witnesses in lawsuits are paid for the time they spend on the case. But a number of independent studies going back to 1969 also have documented the existence of PCBs and a host of other contaminants, including the banned pesticide DDT, in the bay and river. A 2009 report by UWF scientists Mohrherr, Johan Liebens and Ranga Rao may have been the �rst to suggest remediation as an answer: “...the only safe cleanup level for PCBs relative to human consumption of seafood will be sediment concentrations that are below current analytical detection limits,” reads the study. But Mohrherr cautioned that a cleanup of bay hot spots would do little good if PCBs are still coming from the river or plant site. Any cleanup would be expensive and could take many forms, experts have said, including dredging parts of the bay and river below the plant site, or capping contaminated spots with clay. Other ideas include utilizing bacteria that break down the PCBs to less-toxic molecules, a process now under investiga-tion at a number of laboratories, according to published studies. Any course of action could be a huge undertaking. On the Hudson River, named an EPA Superfund site in 1984, crews are dredging 40 miles of river bottom, and plan to replace it with clean soil in a project expected to last another four years and cost more than $500 million. GE has agreed to pay at least part of the cost. Monsanto, like GE, may be able to a�ord an expensive cleanup plan. The company sold the Pensacola nylon plant in 2009, but could still be held liable. Now an agricultural giant, Monsanto reported almost $2.5 billion in annual pro�ts for 2013, the company's annual report shows. The company may have few friends to come to its defense these days: As a leading producer of genetically modi�ed corn, soybean and other crops, Monsanto has earned the ire of a growing number of environmental groups. Monsanto has a history of disregarding environmental problems resulting from their products, said plainti�s' lawyer Don Stewart of Anniston, Ala. “They've been a pretty thuggish company,” he said. Stewart is well familiar with Monsanto's tactics: He was the lead lawyer who in 2002 won a $700 million judgment against Monsanto for extensive PCB pollution around its manufacturing plant in Anniston. (After a brief initial conversation, Stewart did not return emails and phone calls for this article.)

Health Department falling short?

The man who may have done more than anyone to prompt concerns about the PCBs in Escambia waters is Dick Snyder, director of the University of West Florida's Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation. He and colleagues Rao and Natalie Karouna-Renier conducted studies in 2007 and 2008 that showed PCBs in the tissue of a wide variety of �sh, oysters and crab. Concentrations were particu-larly high in striped mullet, bottom feeders that are a staple of many Pensacola-area consumers' diet. The chemicals appear to concentrate in the skin and fatty tissues of the seafood. When PCBs in �sh reach a certain level, the EPA considers that a screening threshold at which consumers should be warned. That means consumers eating the �sh more than once a week stand a one in 10,000 chance of getting cancer over many years. Some of the mullet in Snyder's studies had levels 300 times the EPA threshold, giving consumers a signi�cantly elevated risk if they eat the contaminated mullet on a regular basis. “Consumption of some �n�sh harvested from the Escambia River and Escambia Bay pose a signi�cant risk of cancer and non-cancer health hazards due to contamination from PCBs...” wrote plainti�s' expert Harlee Strauss, a molecular biologist and environmental risk assessment consultant.But Snyder, whose studies are repeatedly quoted in the lawsuit, believes that dredging the bay could do more harm than good. “Disturbing the sediments may well create more exposure than it would solve,” Snyder told PensacolaToday.com. “I think the best outcome was what we did, which was to alert the public to the problem. But, unfortunately, the Florida Department of Health has not continued to monitor the problem and provide updated information.”The state Health Department posts a �sh consumption advisory on its website, warning people not to eat more than one meal a week of skinless striped mullet that was caught in the lower Escambia River or Escambia Bay. But plainti�s in the lawsuit and others have suggested that advisory is inadequate: mullet range far and wide, and could easily feed on PCBs in upper Escambia Bay, only to be caught in Pensacola Bay, in the sound or in the Gulf. “I don't think that advisory does a whole heck of a lot of good,” said Chips Kirschenfeld, senior scientist and division manager for Escambia County's Water Quality and Land Management Division. “You go to a restaurant, you don't know where the �sh comes from.” A few years ago, health o�cials appeared to be more concerned. In late 2007, after the UWF studies and news reports about it were published, the Escambia County Health Depart-ment posted advisory signs at boat launches and secured billboard advertising that explained the risks. But in recent years, those signs have disappeared, and the health department has made no e�ort to post them again, health o�cials said. “A sign like that wouldn't last too long around here, anyway,” said Rick Sconiers, who runs Jim's Fish Camp, a boat

launch and shop near the eastern edge of the U.S. 90 bridge on Escambia Bay. “A �sherman would probably take that down.” Local seafood shops said they have continued to sell mullet, crab and other bay species caught by local �shermen, with little awareness of the dangers. Although experts say that blue crab should be cleaned of its tomalley, or fatty tissues and organs, before it's boiled, “most people just boil them whole,” said Phil Rollo, owner of Rollo's Seafood in Milton, who regularly buys bay crab from local crabbers. “Well, you have given me a lot to think about,” said Alesia Wilkes, a manager at Joe Patti's Seafood in Pensacola, when asked about potential PCBs in local seafood. “We do not post anything in store currently to the e�ects of this, but we would never deny the truth to a customer.” Much of the seafood sold at Joe Patti's comes from outside Escambia Bay, including Mobile Bay and Apalachicola, she said. While some mullet lovers discard the skin these days, local �shermen and seafood sellers all say the same thing: The old-timers like the taste of skin-on mullet. “My dad never took the skin o�,” said Daniel Mabire, who has spent his life on the waters of Escambia Bay. A 2004 survey by UWF, in fact, showed that 40 percent of those Escambia and Santa Rosa residents who eat �sh enjoy it with the skin on. The Santa Rosa County Health Department is in the process of developing paper �yers explaining the �sh advisory, to be left at places where �shing licenses are sold, said Deborah Stilphen, public information o�cer at the department. “It was determined that posting signs would be impractical because of the amount of information that would have to be included,” she said. Santa Rosa and Escambia Health Departments said they have no plans for posting signs or �yers at restaurants or seafood markets, and no plans to include crab in future advisories, despite the worrisome data. “We're constantly pushing people to go to the web site, and we have brochures in the o�ce,” said Marie Mott, public information o�cer for the Escambia Department of Health.

Where are state authorities?

Legally speaking, ordering even a limited cleanup of the bay or river could be problematic. Monsanto and co-defendants in the lawsuit have argued that under the legal doctrine known as primary jurisdiction, only the state Department of Environ-mental Protection can order such remediation. Plainti�s' lawyers and legal scholars, though, said that a court can step in if the state agency shows no signs of taking action. Stewart said that plainti�s and others through the years had, in fact, tried unsuc-cessfully to get the DEP to order the waterways cleaned. And that raises a key question for a number of local environmental activists: If Escambia River and Bay are known to have been contaminated since the early 1970s, and recent studies suggest the contamination is continuing, why hasn't the EPA or DEP shown more interest? Court documents in the case

show that EPA o�cials in 2002 were aware of PCBs continuing to leak into the river, but did not force action. Part of that may have been the result of a decades-long shift in environmental protec-tion nationwide. Thanks to budget cuts and other political concerns, the federal agency now often leaves it to the states to take the lead, news reports show. Dawn Harris-Young with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Atlanta said that when sediment and �sh-tissue levels reach a certain threshold, it's now considered the state's responsibility to take action, perhaps going so far as ordering a �shing ban in the bay. Florida environmental experts say that's less than likely to happen. “The state talks a good show, but they don't really do anything,” said Rich Wiecowicz, a retired wastewater engineer at DEP who studied industrial discharge issues for years. “The DEP has a history of being reluctant to hammer down on industries that provide jobs,” Kirschenfeld said. DEP o�cials declined to comment for this article, except to say the agency has no plans to take any legal action. DEP's own published guidelines suggest that when PCB concentrations in sediment rise above probable e�ects levels, the agency should make it a “high priority” to investigate further and determine what remedial measures are needed. State law also appears to allow the agency to prosecute polluting o�end-ers. Monsanto, in fact, relies on regulators' inaction as a defense: “The lack of a formal regulatory response by DEP and EPA, with respect to PCBs in Escambia Bay, indicates that this is a region where risks of chemical contaminants are low and/or adequately managed,” wrote Charles Menzie, a scienti�c witness for the defendants. The lack of action from the state agencies sounds strikingly similar to what happened in Anniston, Ala., where Monsanto manufactured PCBs for decades. The company failed to fully inform regulators of its poisonous discharges, and state environmental o�cials failed to act, even when they were made aware, according to the 2014 book “Baptized in PCBs,” which documented the Anniston case and mentions the Escambia Bay contamination. It's also possible that local authorities, such as the state prosecutor or county attorney, could bring legal action, some have suggested. Escambia County Attorney Allison Rogers said such an idea “is de�nitely a possibility; I just don't know much

about this situation.” Escambia County may have already taken a step in that direction. In 2008, the county received a $200,000 grant from the Legislature to sample upper bay sediment for a possible remedia-tion project. More than 500 samples showed 25 sites with PCB concentrations at or above the state's probable e�ects level. Most of those were clustered near the mouth of the Escambia River, suggesting that dredging just that area of the bay would remove signi�cant amounts of the chemicals, said Kirschenfeld, who lead the project. But after the recession hit, the Legislature declined to fund any remediation work. “I plan to submit a request again this year,” he said. In the Pensacola lawsuit, other scienti�c experts have produced several reports that have raised a number of red �ags. The reports show that PCBs in high concentrations have been found on the plant site as recently as 2010 and 2012. Soil samplings from 1999 on the plant site showed levels as high as 24,300 parts per billion, or almost 10 times the state's cleanup target levels, the level of cleanliness the state would like to see after a spill has been ordered remediated. In 2011, another soil sample taken near plant holding ponds found PCBs at levels 80 times the cleanup target level. The next year, samplings from the creek bed adjacent to former holding ponds at the site, show Aroclor 1254, Monsanto's most-often used PCB product, at levels ranging from 12 to 350 parts per billion. These sources and others have likely continued to release PCBs into the Escambia River, said plainti�s expert Matson, a professor emeritus in environmental engineering at Pennsylvania State University. “Monsanto documents show that the company had both the knowledge and the technology available to prevent PCBs from being discharged into Eagle's Nest Creek and the Escambia River,” reads Matson's report. At another Monsanto plant, for example, the company built what's known as a “concrete bathtub” to collect all drainage, and used absorbent material to remove contaminants from wastewater, said Matson, who was also a key witness in the Anniston case against Monsanto. The company's neglect dates back decades, the plainti�s argue. In 1971, state environmental authorities, in one of their few actions about this source of pollution, cited Monsanto for violat-ing regulations by allowing PCBs to drain from the plant site. But the company only addressed one source of the drainage, and the state did not follow up, Matson said in his March 2014 deposition. “Here you had an NOV (notice of violation) that if enforced, would indeed have solved the problem, but it was only partially dealt with,” Matson said. “My thinking was that the relationship between the regulatory authorities – the state regulatory authorities and Monsanto – really hadn't changed. They hadn't – because they had put the lid on and suppressed the information about the plant that they were still ignorant on what was going on in the plant.” A $65,000 containment area would have prevented a legacy of contamination, Matson said: “They could have zippered up this plant so that what has happened wouldn't have happened.”

Although the plant manager said in 1969 that the company had stopped using PCBs, evidence shows that high amounts of the compounds were found in sludge in the air compressor tanks in 1995, company workers said in deposi-tions. “Well, the reality is they didn't stop using PCBs and – and the feed pond got horribly contaminated with PCBs, which created a problem in the late '90s as to what to do about it,” Matson said. Monsanto repaired the leaking feed pond, but not before it may have contaminated another area, which ultimately led to runo� into the river, plainti�s experts suggest. The mid and late 1990s is when PCB levels in oysters stopped declining, suggesting that was when additional amounts of PCBs began draining o� the plant site, said plainti�s' expert Edward Garvey, a geochemist who also studied the Hudson River. Another plainti�s' expert raised concerns about continuing pollution after recent soil samplings showed PCBs at �ve spots. “It is evident that PCBs are migrating to the Escambia River and concentrating within the depositional environments of the river,” wrote Ronald Scrudato, director of technology at Global Green Environmental, which specializes in removal of toxic materials from soil and wastewater. “The elevated soil samples collected and analyzed in September 2012 demon-strated that Ascend properties are contributing to the PCB migration to the Escambia River and Bay systems.” “It is likely that the PCBs originating near (the plant site) are the primary source of contamination to �sh in the Escambia River and upper Escambia Bay, as documented by Snyder and Roa,” wrote Garvey.

Not from us, Monsanto says

The defense team has faulted these experts, saying the PCBs found in some samplings were di�erent from the types of PCBs used by Monsanto, and that some of the higher concen-trations were found further downstream, near Plant Crist. Gulf Power o�cials were surprised to hear that claim. “We don't know of any kind of PCB discharge at Plant Crist,” said spokesman Je� Rogers. The utility made an e�ort in the 1990s to remove any traces of PCBs in equipment at the plant, and crews regularly test for hazardous chemicals, he said. Defense consultant Wayne Grip pointed out that in 1999, Gulf Power did obtain a permit to burn waste oil which may have contained PCBs, but Rogers said company engineers have shown that the amount of the compounds in the oil were so small, and were incinerated so completely, that they could not have contaminated any sediment. The defense also has o�ered what a casual observer might call hair-splitting: One section of state law allows damages to be awarded because of a pollution discharge, but only only if the contaminants came from a “terminal facility,” such as the barge dock on the northeast corner of the Monsanto plant site. Monsanto released PCBs only from an

outfall ditch a few hundred yards to the south, so therefore did not violate the law, according to a defense motion. The Monsanto lawyers also o�ered another interest-ing defense: The company couldn't have violated any state sediment pollution standards because Florida has none for PCBs. The DEP didn't establish numerical water quality standards until 1990, and it still has no real sediment standards. The agency has published only Sediment Quality Assessment Guidelines, which encourage investigations of contamination when it rises above a certain level, but do not require any action.

The lawsuit also provides a rare glimpse into Monsanto's corporate mindset in the late 1960s. Shortly after controversy over PCBs spread worldwide, but before contami-nation in Escambia Bay was widely known, Monsanto estab-lished a “PCB Committee” to discuss its options, according to an August 1969 hand-written company memo that was included in the court �les. In Pensacola, the memo notes that state o�cials had visited the nylon plant, but asked “no real searching questions...Lid probably on for the moment.”

Some 45 years after Monsanto Co. allowed some of the world's most dangerous and persistent chemicals to �ow into Escambia Bay, a Pensacola judge has ruled that a massive cleanup of the bay and river is not o� the table. The recent ruling by Escambia County Circuit Judge Jan Shackelford is the latest development in a lawsuit that began in 2008. If the plainti�s prevail, a cleanup could ultimately result in a remediation process that could cost more than $400 million – perhaps something like the years-long e�ort now under way on the Hudson River in New York State, where General Electric Co. dumped the same types of PCB compounds decades ago. The lawsuit was �led by 160 homeowners and businesses around Escambia Bay, who contend that Monsanto and its successor companies damaged their use of the bay and contaminated seafood with the PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, which have been classed as probable human carcinogens. The lawsuit, now in its 37th volume of �lings, has produced a raft of new studies and expert analyses that paint a grim picture of how the companies and regulators may have failed to properly deal with PCB leaks and runo� over the past half-century. Plainti�s' experts contend: The hazardous compounds are still seeping from the plant site in Gonzalez. The plant allowed PCBs to drain into nearby waterways, constituting an unpermitted discharge, in violation of state law. Recent soil and sediment samplings show high levels of the compounds on the plant site, in the river and the bay. Monsanto hid information from regulators and failed to take measures that would have prevented widespread contami-nation. The PCBs threaten dolphins and cormorants because levels in some hot spots are 780 times higher than federal protection limits. PCBs in bay oysters declined from 1989 to 1994, but have remained steady since then – suggesting contaminants are still entering the bay. State and federal authorities have done little to address the contamination, despite guidelines that call for concern.

The defendant companies have denied any wrongdo-ing, and said they have worked closely with regulators to prevent discharges of the chemicals to the river and bay. “The property owners who brought this lawsuit do not have PCBs from the plant on their properties, in their homes, or in the sediments adjacent to their properties,” reads a statement from Pensacola attorney Steve Bolton, who represents the defendant companies. “They, as can the entire Escambia Bay, Pensacola, and Milton communities, safely enjoy the wide range of bene�ts the bay provides.”

The companies declined to talk about the speci�cs of the litigation, but said a cleanup of the bay would be “unneces-sary, given the absence of any health risk posed by the ultra-low concentrations in the Bay,” Bolton said. Defendants Monsanto, its successor companies Solutia Inc. and Pharmacia Inc. and the new plant owner, Ascend Performance Materials, early on o�ered a $1,000 settlement for each plainti�, which most of them rejected. The case, known as John Allen et al vs. Monsanto et al, may go to trial early next year. Both sides have asked for a jury. Since initial news reports when the suit was �led, though, the health threats highlighted by the case have been all but forgotten by the public and by state health authorities. Bayside residents and scientists say that state and local agencies have done little to warn seafood lovers or to address the toxic sites. Some locals have taken it upon themselves to spread the word. “Don't eat the mullet, and don't eat the crab unless you take the fatty tissue out �rst,” plainti� Sherry Starling, a former state environmental inspector, said recently at a public gather-ing of concerned citizens.

The long arm of PCBs

Polychlorinated biphenyls, produced by combining chlorine and benzene, were once hailed as miracle compounds by industry because they can withstand extreme heat while retaining their lubricating and insulating properties in electrical and other equipment. Although most are oily compounds, they are heavier than water and sink into sediment. By the 1970s, PCBs had been shown to cause cancer and other health problems, kill marine life and damage bird eggs the world over. They were mostly banned by Congress in 1977, but some PCBs break down so slowly that they could be toxic in sediment for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years, studies show. Monsanto, a global company that started more than 100 years ago and was the sole U.S. manufacturer of PCBs, has acknowledged that PCBs were used at its nylon plant on the Escambia River, eight miles north of Pensacola, and that they

leaked from air compressors in late 1960s. Documents show the plant allowed as much as three gallons a day to drain into ditches that led to the river. The defendant companies have said that any seepage from the site today is “de minimus,” and contaminated areas in the bay are at concentrations below levels of concern. Defense experts have also said that plainti�s' studies have misinterpreted sediment data, and suggest that PCBs on the bay �oor could also have come from Gulf Power's Plant Crist generating station on the river, and from the former Air Products and Chemicals plant in Pace, which has a treated-waste discharge on the east side of the bay. Those companies strongly refute that suggestion, saying that they have no evidence that PCBs were ever used in quantity or spilled at their plant sites. The plainti�s are asking for monetary damages, but also that the defendants be required to pay for remediation of the contaminated areas around the plant site, in the riverbed and on the �oor of Escambia Bay, where mullet, crab and other marine life live and feed. The defendants this summer asked the judge to dismiss that part of the lawsuit, arguing that remedia-

tion would cost far more than any damages the plainti�s may have su�ered. After weeks of deliberation, Shackelford denied the request, and agreed with the plainti�s that before remediation could be ordered, a thorough site plan of the bay and contami-nated lands would have to be done, a step that itself could cost between $2.6 million and $5.1 million, according to expert witnesses the judge relied on. “The ecological threats...from exposures to PCBs in Escambia Bay will persist until the sources of PCBs, including the Monsanto site, and the environmental media are remediated,” wrote plainti�s' expert Jerome Cura, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Group in Massachusetts. Because PCBs build up in the food chain, even tiny amounts in sediment can end up being hazardous to wildlife and humans, experts said. Some of the studies have shown hot spots as high as 118 parts per billion (ppb) in bay sediment and 3,690 parts ppb in the river sediment. Florida sediment guidelines set 22 ppb as a “possible e�ects level” and

189 ppb as a “probable e�ects level” for biological damage. But Carl Mohrherr, a retired UWF biologist, and others said those state thresholds are misleadingly high: They only refer to immediate e�ects on organisms, and do not re�ect how the poison can bioaccumulate to more dangerous levels. Some plainti�s' experts suggested there's no safe level for the hardy compounds, and that Monsanto should have taken more precautions.“Monsanto documents show that the company had both the knowledge and technology available to prevent PCBs from being discharged into Eagle's Nest Creek and the Escambia River,” another plainti�s' witness, professor Jack Matson of Pennsylvania State University, reported. Most expert witnesses in lawsuits are paid for the time they spend on the case. But a number of independent studies going back to 1969 also have documented the existence of PCBs and a host of other contaminants, including the banned pesticide DDT, in the bay and river. A 2009 report by UWF scientists Mohrherr, Johan Liebens and Ranga Rao may have been the �rst to suggest remediation as an answer: “...the only safe cleanup level for PCBs relative to human consumption of seafood will be sediment concentrations that are below current analytical detection limits,” reads the study. But Mohrherr cautioned that a cleanup of bay hot spots would do little good if PCBs are still coming from the river or plant site. Any cleanup would be expensive and could take many forms, experts have said, including dredging parts of the bay and river below the plant site, or capping contaminated spots with clay. Other ideas include utilizing bacteria that break down the PCBs to less-toxic molecules, a process now under investiga-tion at a number of laboratories, according to published studies. Any course of action could be a huge undertaking. On the Hudson River, named an EPA Superfund site in 1984, crews are dredging 40 miles of river bottom, and plan to replace it with clean soil in a project expected to last another four years and cost more than $500 million. GE has agreed to pay at least part of the cost. Monsanto, like GE, may be able to a�ord an expensive cleanup plan. The company sold the Pensacola nylon plant in 2009, but could still be held liable. Now an agricultural giant, Monsanto reported almost $2.5 billion in annual pro�ts for 2013, the company's annual report shows. The company may have few friends to come to its defense these days: As a leading producer of genetically modi�ed corn, soybean and other crops, Monsanto has earned the ire of a growing number of environmental groups. Monsanto has a history of disregarding environmental problems resulting from their products, said plainti�s' lawyer Don Stewart of Anniston, Ala. “They've been a pretty thuggish company,” he said. Stewart is well familiar with Monsanto's tactics: He was the lead lawyer who in 2002 won a $700 million judgment against Monsanto for extensive PCB pollution around its manufacturing plant in Anniston. (After a brief initial conversation, Stewart did not return emails and phone calls for this article.)

Health Department falling short?

The man who may have done more than anyone to prompt concerns about the PCBs in Escambia waters is Dick Snyder, director of the University of West Florida's Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation. He and colleagues Rao and Natalie Karouna-Renier conducted studies in 2007 and 2008 that showed PCBs in the tissue of a wide variety of �sh, oysters and crab. Concentrations were particu-larly high in striped mullet, bottom feeders that are a staple of many Pensacola-area consumers' diet. The chemicals appear to concentrate in the skin and fatty tissues of the seafood. When PCBs in �sh reach a certain level, the EPA considers that a screening threshold at which consumers should be warned. That means consumers eating the �sh more than once a week stand a one in 10,000 chance of getting cancer over many years. Some of the mullet in Snyder's studies had levels 300 times the EPA threshold, giving consumers a signi�cantly elevated risk if they eat the contaminated mullet on a regular basis. “Consumption of some �n�sh harvested from the Escambia River and Escambia Bay pose a signi�cant risk of cancer and non-cancer health hazards due to contamination from PCBs...” wrote plainti�s' expert Harlee Strauss, a molecular biologist and environmental risk assessment consultant.But Snyder, whose studies are repeatedly quoted in the lawsuit, believes that dredging the bay could do more harm than good. “Disturbing the sediments may well create more exposure than it would solve,” Snyder told PensacolaToday.com. “I think the best outcome was what we did, which was to alert the public to the problem. But, unfortunately, the Florida Department of Health has not continued to monitor the problem and provide updated information.”The state Health Department posts a �sh consumption advisory on its website, warning people not to eat more than one meal a week of skinless striped mullet that was caught in the lower Escambia River or Escambia Bay. But plainti�s in the lawsuit and others have suggested that advisory is inadequate: mullet range far and wide, and could easily feed on PCBs in upper Escambia Bay, only to be caught in Pensacola Bay, in the sound or in the Gulf. “I don't think that advisory does a whole heck of a lot of good,” said Chips Kirschenfeld, senior scientist and division manager for Escambia County's Water Quality and Land Management Division. “You go to a restaurant, you don't know where the �sh comes from.” A few years ago, health o�cials appeared to be more concerned. In late 2007, after the UWF studies and news reports about it were published, the Escambia County Health Depart-ment posted advisory signs at boat launches and secured billboard advertising that explained the risks. But in recent years, those signs have disappeared, and the health department has made no e�ort to post them again, health o�cials said. “A sign like that wouldn't last too long around here, anyway,” said Rick Sconiers, who runs Jim's Fish Camp, a boat

launch and shop near the eastern edge of the U.S. 90 bridge on Escambia Bay. “A �sherman would probably take that down.” Local seafood shops said they have continued to sell mullet, crab and other bay species caught by local �shermen, with little awareness of the dangers. Although experts say that blue crab should be cleaned of its tomalley, or fatty tissues and organs, before it's boiled, “most people just boil them whole,” said Phil Rollo, owner of Rollo's Seafood in Milton, who regularly buys bay crab from local crabbers. “Well, you have given me a lot to think about,” said Alesia Wilkes, a manager at Joe Patti's Seafood in Pensacola, when asked about potential PCBs in local seafood. “We do not post anything in store currently to the e�ects of this, but we would never deny the truth to a customer.” Much of the seafood sold at Joe Patti's comes from outside Escambia Bay, including Mobile Bay and Apalachicola, she said. While some mullet lovers discard the skin these days, local �shermen and seafood sellers all say the same thing: The old-timers like the taste of skin-on mullet. “My dad never took the skin o�,” said Daniel Mabire, who has spent his life on the waters of Escambia Bay. A 2004 survey by UWF, in fact, showed that 40 percent of those Escambia and Santa Rosa residents who eat �sh enjoy it with the skin on. The Santa Rosa County Health Department is in the process of developing paper �yers explaining the �sh advisory, to be left at places where �shing licenses are sold, said Deborah Stilphen, public information o�cer at the department. “It was determined that posting signs would be impractical because of the amount of information that would have to be included,” she said. Santa Rosa and Escambia Health Departments said they have no plans for posting signs or �yers at restaurants or seafood markets, and no plans to include crab in future advisories, despite the worrisome data. “We're constantly pushing people to go to the web site, and we have brochures in the o�ce,” said Marie Mott, public information o�cer for the Escambia Department of Health.

Where are state authorities?

Legally speaking, ordering even a limited cleanup of the bay or river could be problematic. Monsanto and co-defendants in the lawsuit have argued that under the legal doctrine known as primary jurisdiction, only the state Department of Environ-mental Protection can order such remediation. Plainti�s' lawyers and legal scholars, though, said that a court can step in if the state agency shows no signs of taking action. Stewart said that plainti�s and others through the years had, in fact, tried unsuc-cessfully to get the DEP to order the waterways cleaned. And that raises a key question for a number of local environmental activists: If Escambia River and Bay are known to have been contaminated since the early 1970s, and recent studies suggest the contamination is continuing, why hasn't the EPA or DEP shown more interest? Court documents in the case

show that EPA o�cials in 2002 were aware of PCBs continuing to leak into the river, but did not force action. Part of that may have been the result of a decades-long shift in environmental protec-tion nationwide. Thanks to budget cuts and other political concerns, the federal agency now often leaves it to the states to take the lead, news reports show. Dawn Harris-Young with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Atlanta said that when sediment and �sh-tissue levels reach a certain threshold, it's now considered the state's responsibility to take action, perhaps going so far as ordering a �shing ban in the bay. Florida environmental experts say that's less than likely to happen. “The state talks a good show, but they don't really do anything,” said Rich Wiecowicz, a retired wastewater engineer at DEP who studied industrial discharge issues for years. “The DEP has a history of being reluctant to hammer down on industries that provide jobs,” Kirschenfeld said. DEP o�cials declined to comment for this article, except to say the agency has no plans to take any legal action. DEP's own published guidelines suggest that when PCB concentrations in sediment rise above probable e�ects levels, the agency should make it a “high priority” to investigate further and determine what remedial measures are needed. State law also appears to allow the agency to prosecute polluting o�end-ers. Monsanto, in fact, relies on regulators' inaction as a defense: “The lack of a formal regulatory response by DEP and EPA, with respect to PCBs in Escambia Bay, indicates that this is a region where risks of chemical contaminants are low and/or adequately managed,” wrote Charles Menzie, a scienti�c witness for the defendants. The lack of action from the state agencies sounds strikingly similar to what happened in Anniston, Ala., where Monsanto manufactured PCBs for decades. The company failed to fully inform regulators of its poisonous discharges, and state environmental o�cials failed to act, even when they were made aware, according to the 2014 book “Baptized in PCBs,” which documented the Anniston case and mentions the Escambia Bay contamination. It's also possible that local authorities, such as the state prosecutor or county attorney, could bring legal action, some have suggested. Escambia County Attorney Allison Rogers said such an idea “is de�nitely a possibility; I just don't know much

about this situation.” Escambia County may have already taken a step in that direction. In 2008, the county received a $200,000 grant from the Legislature to sample upper bay sediment for a possible remedia-tion project. More than 500 samples showed 25 sites with PCB concentrations at or above the state's probable e�ects level. Most of those were clustered near the mouth of the Escambia River, suggesting that dredging just that area of the bay would remove signi�cant amounts of the chemicals, said Kirschenfeld, who lead the project. But after the recession hit, the Legislature declined to fund any remediation work. “I plan to submit a request again this year,” he said. In the Pensacola lawsuit, other scienti�c experts have produced several reports that have raised a number of red �ags. The reports show that PCBs in high concentrations have been found on the plant site as recently as 2010 and 2012. Soil samplings from 1999 on the plant site showed levels as high as 24,300 parts per billion, or almost 10 times the state's cleanup target levels, the level of cleanliness the state would like to see after a spill has been ordered remediated. In 2011, another soil sample taken near plant holding ponds found PCBs at levels 80 times the cleanup target level. The next year, samplings from the creek bed adjacent to former holding ponds at the site, show Aroclor 1254, Monsanto's most-often used PCB product, at levels ranging from 12 to 350 parts per billion. These sources and others have likely continued to release PCBs into the Escambia River, said plainti�s expert Matson, a professor emeritus in environmental engineering at Pennsylvania State University. “Monsanto documents show that the company had both the knowledge and the technology available to prevent PCBs from being discharged into Eagle's Nest Creek and the Escambia River,” reads Matson's report. At another Monsanto plant, for example, the company built what's known as a “concrete bathtub” to collect all drainage, and used absorbent material to remove contaminants from wastewater, said Matson, who was also a key witness in the Anniston case against Monsanto. The company's neglect dates back decades, the plainti�s argue. In 1971, state environmental authorities, in one of their few actions about this source of pollution, cited Monsanto for violat-ing regulations by allowing PCBs to drain from the plant site. But the company only addressed one source of the drainage, and the state did not follow up, Matson said in his March 2014 deposition. “Here you had an NOV (notice of violation) that if enforced, would indeed have solved the problem, but it was only partially dealt with,” Matson said. “My thinking was that the relationship between the regulatory authorities – the state regulatory authorities and Monsanto – really hadn't changed. They hadn't – because they had put the lid on and suppressed the information about the plant that they were still ignorant on what was going on in the plant.” A $65,000 containment area would have prevented a legacy of contamination, Matson said: “They could have zippered up this plant so that what has happened wouldn't have happened.”

Although the plant manager said in 1969 that the company had stopped using PCBs, evidence shows that high amounts of the compounds were found in sludge in the air compressor tanks in 1995, company workers said in deposi-tions. “Well, the reality is they didn't stop using PCBs and – and the feed pond got horribly contaminated with PCBs, which created a problem in the late '90s as to what to do about it,” Matson said. Monsanto repaired the leaking feed pond, but not before it may have contaminated another area, which ultimately led to runo� into the river, plainti�s experts suggest. The mid and late 1990s is when PCB levels in oysters stopped declining, suggesting that was when additional amounts of PCBs began draining o� the plant site, said plainti�s' expert Edward Garvey, a geochemist who also studied the Hudson River. Another plainti�s' expert raised concerns about continuing pollution after recent soil samplings showed PCBs at �ve spots. “It is evident that PCBs are migrating to the Escambia River and concentrating within the depositional environments of the river,” wrote Ronald Scrudato, director of technology at Global Green Environmental, which specializes in removal of toxic materials from soil and wastewater. “The elevated soil samples collected and analyzed in September 2012 demon-strated that Ascend properties are contributing to the PCB migration to the Escambia River and Bay systems.” “It is likely that the PCBs originating near (the plant site) are the primary source of contamination to �sh in the Escambia River and upper Escambia Bay, as documented by Snyder and Roa,” wrote Garvey.

Not from us, Monsanto says

The defense team has faulted these experts, saying the PCBs found in some samplings were di�erent from the types of PCBs used by Monsanto, and that some of the higher concen-trations were found further downstream, near Plant Crist. Gulf Power o�cials were surprised to hear that claim. “We don't know of any kind of PCB discharge at Plant Crist,” said spokesman Je� Rogers. The utility made an e�ort in the 1990s to remove any traces of PCBs in equipment at the plant, and crews regularly test for hazardous chemicals, he said. Defense consultant Wayne Grip pointed out that in 1999, Gulf Power did obtain a permit to burn waste oil which may have contained PCBs, but Rogers said company engineers have shown that the amount of the compounds in the oil were so small, and were incinerated so completely, that they could not have contaminated any sediment. The defense also has o�ered what a casual observer might call hair-splitting: One section of state law allows damages to be awarded because of a pollution discharge, but only only if the contaminants came from a “terminal facility,” such as the barge dock on the northeast corner of the Monsanto plant site. Monsanto released PCBs only from an

October 2014

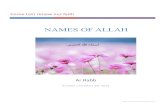

Kirschenfeld, Escambia County; Snyder and Rao; Mohrherr and Liebens; Google Earth. Sampling locations are approximate.

Beaver Creek

Chem

stra

nd R

oad

Scale: 1 mile

N

What lies beneath... the plant site, and is still draining into Escambia River and Escambia Bay. Defendants dispute these

Health advisories recommend no more than one meal per week of skinless mullet from Escambia Bay and River, but

warning doesn’t go far enough.

Escambia River

CreekNest

former Monsanto

nylon plant(now Ascend Performance

Materials)

Map data ©2014 Google 1 mi

Traffic, B icycling, Terrain, Directions

enlarged area

High levels of PCBs found in sediment here

in 2008-2009

Gulf Power’sCrist steam plant

Escambia Bay

Monsanto plant

Some of the highest concentrations

found in sediment here in 2010

High levels of PCBs found in sediment

here in 2010.

PCBs found in 2011 as high as

210,000 ppb.

High levels found in sediment here in

2010.

Building 4081999 samples showed PCBs at

24.3 ppm, above the state threshold.

On site of former emergency

into creek, experts argue.

South Outfall2012 soil samples showed some of the highest levels.

Eagle’s

former Monsanto

nylon plant(now Ascend Performance

Materials)

graphic by William Rabb

outfall ditch a few hundred yards to the south, so therefore did not violate the law, according to a defense motion. The Monsanto lawyers also o�ered another interest-ing defense: The company couldn't have violated any state sediment pollution standards because Florida has none for PCBs. The DEP didn't establish numerical water quality standards until 1990, and it still has no real sediment standards. The agency has published only Sediment Quality Assessment Guidelines, which encourage investigations of contamination when it rises above a certain level, but do not require any action.

The lawsuit also provides a rare glimpse into Monsanto's corporate mindset in the late 1960s. Shortly after controversy over PCBs spread worldwide, but before contami-nation in Escambia Bay was widely known, Monsanto estab-lished a “PCB Committee” to discuss its options, according to an August 1969 hand-written company memo that was included in the court �les. In Pensacola, the memo notes that state o�cials had visited the nylon plant, but asked “no real searching questions...Lid probably on for the moment.”

October 2014

Some 45 years after Monsanto Co. allowed some of the world's most dangerous and persistent chemicals to �ow into Escambia Bay, a Pensacola judge has ruled that a massive cleanup of the bay and river is not o� the table. The recent ruling by Escambia County Circuit Judge Jan Shackelford is the latest development in a lawsuit that began in 2008. If the plainti�s prevail, a cleanup could ultimately result in a remediation process that could cost more than $400 million – perhaps something like the years-long e�ort now under way on the Hudson River in New York State, where General Electric Co. dumped the same types of PCB compounds decades ago. The lawsuit was �led by 160 homeowners and businesses around Escambia Bay, who contend that Monsanto and its successor companies damaged their use of the bay and contaminated seafood with the PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, which have been classed as probable human carcinogens. The lawsuit, now in its 37th volume of �lings, has produced a raft of new studies and expert analyses that paint a grim picture of how the companies and regulators may have failed to properly deal with PCB leaks and runo� over the past half-century. Plainti�s' experts contend: The hazardous compounds are still seeping from the plant site in Gonzalez. The plant allowed PCBs to drain into nearby waterways, constituting an unpermitted discharge, in violation of state law. Recent soil and sediment samplings show high levels of the compounds on the plant site, in the river and the bay. Monsanto hid information from regulators and failed to take measures that would have prevented widespread contami-nation. The PCBs threaten dolphins and cormorants because levels in some hot spots are 780 times higher than federal protection limits. PCBs in bay oysters declined from 1989 to 1994, but have remained steady since then – suggesting contaminants are still entering the bay. State and federal authorities have done little to address the contamination, despite guidelines that call for concern.

The defendant companies have denied any wrongdo-ing, and said they have worked closely with regulators to prevent discharges of the chemicals to the river and bay. “The property owners who brought this lawsuit do not have PCBs from the plant on their properties, in their homes, or in the sediments adjacent to their properties,” reads a statement from Pensacola attorney Steve Bolton, who represents the defendant companies. “They, as can the entire Escambia Bay, Pensacola, and Milton communities, safely enjoy the wide range of bene�ts the bay provides.”

The companies declined to talk about the speci�cs of the litigation, but said a cleanup of the bay would be “unneces-sary, given the absence of any health risk posed by the ultra-low concentrations in the Bay,” Bolton said. Defendants Monsanto, its successor companies Solutia Inc. and Pharmacia Inc. and the new plant owner, Ascend Performance Materials, early on o�ered a $1,000 settlement for each plainti�, which most of them rejected. The case, known as John Allen et al vs. Monsanto et al, may go to trial early next year. Both sides have asked for a jury. Since initial news reports when the suit was �led, though, the health threats highlighted by the case have been all but forgotten by the public and by state health authorities. Bayside residents and scientists say that state and local agencies have done little to warn seafood lovers or to address the toxic sites. Some locals have taken it upon themselves to spread the word. “Don't eat the mullet, and don't eat the crab unless you take the fatty tissue out �rst,” plainti� Sherry Starling, a former state environmental inspector, said recently at a public gather-ing of concerned citizens.

The long arm of PCBs

Polychlorinated biphenyls, produced by combining chlorine and benzene, were once hailed as miracle compounds by industry because they can withstand extreme heat while retaining their lubricating and insulating properties in electrical and other equipment. Although most are oily compounds, they are heavier than water and sink into sediment. By the 1970s, PCBs had been shown to cause cancer and other health problems, kill marine life and damage bird eggs the world over. They were mostly banned by Congress in 1977, but some PCBs break down so slowly that they could be toxic in sediment for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years, studies show. Monsanto, a global company that started more than 100 years ago and was the sole U.S. manufacturer of PCBs, has acknowledged that PCBs were used at its nylon plant on the Escambia River, eight miles north of Pensacola, and that they

leaked from air compressors in late 1960s. Documents show the plant allowed as much as three gallons a day to drain into ditches that led to the river. The defendant companies have said that any seepage from the site today is “de minimus,” and contaminated areas in the bay are at concentrations below levels of concern. Defense experts have also said that plainti�s' studies have misinterpreted sediment data, and suggest that PCBs on the bay �oor could also have come from Gulf Power's Plant Crist generating station on the river, and from the former Air Products and Chemicals plant in Pace, which has a treated-waste discharge on the east side of the bay. Those companies strongly refute that suggestion, saying that they have no evidence that PCBs were ever used in quantity or spilled at their plant sites. The plainti�s are asking for monetary damages, but also that the defendants be required to pay for remediation of the contaminated areas around the plant site, in the riverbed and on the �oor of Escambia Bay, where mullet, crab and other marine life live and feed. The defendants this summer asked the judge to dismiss that part of the lawsuit, arguing that remedia-

tion would cost far more than any damages the plainti�s may have su�ered. After weeks of deliberation, Shackelford denied the request, and agreed with the plainti�s that before remediation could be ordered, a thorough site plan of the bay and contami-nated lands would have to be done, a step that itself could cost between $2.6 million and $5.1 million, according to expert witnesses the judge relied on. “The ecological threats...from exposures to PCBs in Escambia Bay will persist until the sources of PCBs, including the Monsanto site, and the environmental media are remediated,” wrote plainti�s' expert Jerome Cura, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Group in Massachusetts. Because PCBs build up in the food chain, even tiny amounts in sediment can end up being hazardous to wildlife and humans, experts said. Some of the studies have shown hot spots as high as 118 parts per billion (ppb) in bay sediment and 3,690 parts ppb in the river sediment. Florida sediment guidelines set 22 ppb as a “possible e�ects level” and

189 ppb as a “probable e�ects level” for biological damage. But Carl Mohrherr, a retired UWF biologist, and others said those state thresholds are misleadingly high: They only refer to immediate e�ects on organisms, and do not re�ect how the poison can bioaccumulate to more dangerous levels. Some plainti�s' experts suggested there's no safe level for the hardy compounds, and that Monsanto should have taken more precautions.“Monsanto documents show that the company had both the knowledge and technology available to prevent PCBs from being discharged into Eagle's Nest Creek and the Escambia River,” another plainti�s' witness, professor Jack Matson of Pennsylvania State University, reported. Most expert witnesses in lawsuits are paid for the time they spend on the case. But a number of independent studies going back to 1969 also have documented the existence of PCBs and a host of other contaminants, including the banned pesticide DDT, in the bay and river. A 2009 report by UWF scientists Mohrherr, Johan Liebens and Ranga Rao may have been the �rst to suggest remediation as an answer: “...the only safe cleanup level for PCBs relative to human consumption of seafood will be sediment concentrations that are below current analytical detection limits,” reads the study. But Mohrherr cautioned that a cleanup of bay hot spots would do little good if PCBs are still coming from the river or plant site. Any cleanup would be expensive and could take many forms, experts have said, including dredging parts of the bay and river below the plant site, or capping contaminated spots with clay. Other ideas include utilizing bacteria that break down the PCBs to less-toxic molecules, a process now under investiga-tion at a number of laboratories, according to published studies. Any course of action could be a huge undertaking. On the Hudson River, named an EPA Superfund site in 1984, crews are dredging 40 miles of river bottom, and plan to replace it with clean soil in a project expected to last another four years and cost more than $500 million. GE has agreed to pay at least part of the cost. Monsanto, like GE, may be able to a�ord an expensive cleanup plan. The company sold the Pensacola nylon plant in 2009, but could still be held liable. Now an agricultural giant, Monsanto reported almost $2.5 billion in annual pro�ts for 2013, the company's annual report shows. The company may have few friends to come to its defense these days: As a leading producer of genetically modi�ed corn, soybean and other crops, Monsanto has earned the ire of a growing number of environmental groups. Monsanto has a history of disregarding environmental problems resulting from their products, said plainti�s' lawyer Don Stewart of Anniston, Ala. “They've been a pretty thuggish company,” he said. Stewart is well familiar with Monsanto's tactics: He was the lead lawyer who in 2002 won a $700 million judgment against Monsanto for extensive PCB pollution around its manufacturing plant in Anniston. (After a brief initial conversation, Stewart did not return emails and phone calls for this article.)

Health Department falling short?

The man who may have done more than anyone to prompt concerns about the PCBs in Escambia waters is Dick Snyder, director of the University of West Florida's Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation. He and colleagues Rao and Natalie Karouna-Renier conducted studies in 2007 and 2008 that showed PCBs in the tissue of a wide variety of �sh, oysters and crab. Concentrations were particu-larly high in striped mullet, bottom feeders that are a staple of many Pensacola-area consumers' diet. The chemicals appear to concentrate in the skin and fatty tissues of the seafood. When PCBs in �sh reach a certain level, the EPA considers that a screening threshold at which consumers should be warned. That means consumers eating the �sh more than once a week stand a one in 10,000 chance of getting cancer over many years. Some of the mullet in Snyder's studies had levels 300 times the EPA threshold, giving consumers a signi�cantly elevated risk if they eat the contaminated mullet on a regular basis. “Consumption of some �n�sh harvested from the Escambia River and Escambia Bay pose a signi�cant risk of cancer and non-cancer health hazards due to contamination from PCBs...” wrote plainti�s' expert Harlee Strauss, a molecular biologist and environmental risk assessment consultant.But Snyder, whose studies are repeatedly quoted in the lawsuit, believes that dredging the bay could do more harm than good. “Disturbing the sediments may well create more exposure than it would solve,” Snyder told PensacolaToday.com. “I think the best outcome was what we did, which was to alert the public to the problem. But, unfortunately, the Florida Department of Health has not continued to monitor the problem and provide updated information.”The state Health Department posts a �sh consumption advisory on its website, warning people not to eat more than one meal a week of skinless striped mullet that was caught in the lower Escambia River or Escambia Bay. But plainti�s in the lawsuit and others have suggested that advisory is inadequate: mullet range far and wide, and could easily feed on PCBs in upper Escambia Bay, only to be caught in Pensacola Bay, in the sound or in the Gulf. “I don't think that advisory does a whole heck of a lot of good,” said Chips Kirschenfeld, senior scientist and division manager for Escambia County's Water Quality and Land Management Division. “You go to a restaurant, you don't know where the �sh comes from.” A few years ago, health o�cials appeared to be more concerned. In late 2007, after the UWF studies and news reports about it were published, the Escambia County Health Depart-ment posted advisory signs at boat launches and secured billboard advertising that explained the risks. But in recent years, those signs have disappeared, and the health department has made no e�ort to post them again, health o�cials said. “A sign like that wouldn't last too long around here, anyway,” said Rick Sconiers, who runs Jim's Fish Camp, a boat

launch and shop near the eastern edge of the U.S. 90 bridge on Escambia Bay. “A �sherman would probably take that down.” Local seafood shops said they have continued to sell mullet, crab and other bay species caught by local �shermen, with little awareness of the dangers. Although experts say that blue crab should be cleaned of its tomalley, or fatty tissues and organs, before it's boiled, “most people just boil them whole,” said Phil Rollo, owner of Rollo's Seafood in Milton, who regularly buys bay crab from local crabbers. “Well, you have given me a lot to think about,” said Alesia Wilkes, a manager at Joe Patti's Seafood in Pensacola, when asked about potential PCBs in local seafood. “We do not post anything in store currently to the e�ects of this, but we would never deny the truth to a customer.” Much of the seafood sold at Joe Patti's comes from outside Escambia Bay, including Mobile Bay and Apalachicola, she said. While some mullet lovers discard the skin these days, local �shermen and seafood sellers all say the same thing: The old-timers like the taste of skin-on mullet. “My dad never took the skin o�,” said Daniel Mabire, who has spent his life on the waters of Escambia Bay. A 2004 survey by UWF, in fact, showed that 40 percent of those Escambia and Santa Rosa residents who eat �sh enjoy it with the skin on. The Santa Rosa County Health Department is in the process of developing paper �yers explaining the �sh advisory, to be left at places where �shing licenses are sold, said Deborah Stilphen, public information o�cer at the department. “It was determined that posting signs would be impractical because of the amount of information that would have to be included,” she said. Santa Rosa and Escambia Health Departments said they have no plans for posting signs or �yers at restaurants or seafood markets, and no plans to include crab in future advisories, despite the worrisome data. “We're constantly pushing people to go to the web site, and we have brochures in the o�ce,” said Marie Mott, public information o�cer for the Escambia Department of Health.

Where are state authorities?

Legally speaking, ordering even a limited cleanup of the bay or river could be problematic. Monsanto and co-defendants in the lawsuit have argued that under the legal doctrine known as primary jurisdiction, only the state Department of Environ-mental Protection can order such remediation. Plainti�s' lawyers and legal scholars, though, said that a court can step in if the state agency shows no signs of taking action. Stewart said that plainti�s and others through the years had, in fact, tried unsuc-cessfully to get the DEP to order the waterways cleaned. And that raises a key question for a number of local environmental activists: If Escambia River and Bay are known to have been contaminated since the early 1970s, and recent studies suggest the contamination is continuing, why hasn't the EPA or DEP shown more interest? Court documents in the case

show that EPA o�cials in 2002 were aware of PCBs continuing to leak into the river, but did not force action. Part of that may have been the result of a decades-long shift in environmental protec-tion nationwide. Thanks to budget cuts and other political concerns, the federal agency now often leaves it to the states to take the lead, news reports show. Dawn Harris-Young with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Atlanta said that when sediment and �sh-tissue levels reach a certain threshold, it's now considered the state's responsibility to take action, perhaps going so far as ordering a �shing ban in the bay. Florida environmental experts say that's less than likely to happen. “The state talks a good show, but they don't really do anything,” said Rich Wiecowicz, a retired wastewater engineer at DEP who studied industrial discharge issues for years. “The DEP has a history of being reluctant to hammer down on industries that provide jobs,” Kirschenfeld said. DEP o�cials declined to comment for this article, except to say the agency has no plans to take any legal action. DEP's own published guidelines suggest that when PCB concentrations in sediment rise above probable e�ects levels, the agency should make it a “high priority” to investigate further and determine what remedial measures are needed. State law also appears to allow the agency to prosecute polluting o�end-ers. Monsanto, in fact, relies on regulators' inaction as a defense: “The lack of a formal regulatory response by DEP and EPA, with respect to PCBs in Escambia Bay, indicates that this is a region where risks of chemical contaminants are low and/or adequately managed,” wrote Charles Menzie, a scienti�c witness for the defendants. The lack of action from the state agencies sounds strikingly similar to what happened in Anniston, Ala., where Monsanto manufactured PCBs for decades. The company failed to fully inform regulators of its poisonous discharges, and state environmental o�cials failed to act, even when they were made aware, according to the 2014 book “Baptized in PCBs,” which documented the Anniston case and mentions the Escambia Bay contamination. It's also possible that local authorities, such as the state prosecutor or county attorney, could bring legal action, some have suggested. Escambia County Attorney Allison Rogers said such an idea “is de�nitely a possibility; I just don't know much

about this situation.” Escambia County may have already taken a step in that direction. In 2008, the county received a $200,000 grant from the Legislature to sample upper bay sediment for a possible remedia-tion project. More than 500 samples showed 25 sites with PCB concentrations at or above the state's probable e�ects level. Most of those were clustered near the mouth of the Escambia River, suggesting that dredging just that area of the bay would remove signi�cant amounts of the chemicals, said Kirschenfeld, who lead the project. But after the recession hit, the Legislature declined to fund any remediation work. “I plan to submit a request again this year,” he said. In the Pensacola lawsuit, other scienti�c experts have produced several reports that have raised a number of red �ags. The reports show that PCBs in high concentrations have been found on the plant site as recently as 2010 and 2012. Soil samplings from 1999 on the plant site showed levels as high as 24,300 parts per billion, or almost 10 times the state's cleanup target levels, the level of cleanliness the state would like to see after a spill has been ordered remediated. In 2011, another soil sample taken near plant holding ponds found PCBs at levels 80 times the cleanup target level. The next year, samplings from the creek bed adjacent to former holding ponds at the site, show Aroclor 1254, Monsanto's most-often used PCB product, at levels ranging from 12 to 350 parts per billion. These sources and others have likely continued to release PCBs into the Escambia River, said plainti�s expert Matson, a professor emeritus in environmental engineering at Pennsylvania State University. “Monsanto documents show that the company had both the knowledge and the technology available to prevent PCBs from being discharged into Eagle's Nest Creek and the Escambia River,” reads Matson's report. At another Monsanto plant, for example, the company built what's known as a “concrete bathtub” to collect all drainage, and used absorbent material to remove contaminants from wastewater, said Matson, who was also a key witness in the Anniston case against Monsanto. The company's neglect dates back decades, the plainti�s argue. In 1971, state environmental authorities, in one of their few actions about this source of pollution, cited Monsanto for violat-ing regulations by allowing PCBs to drain from the plant site. But the company only addressed one source of the drainage, and the state did not follow up, Matson said in his March 2014 deposition. “Here you had an NOV (notice of violation) that if enforced, would indeed have solved the problem, but it was only partially dealt with,” Matson said. “My thinking was that the relationship between the regulatory authorities – the state regulatory authorities and Monsanto – really hadn't changed. They hadn't – because they had put the lid on and suppressed the information about the plant that they were still ignorant on what was going on in the plant.” A $65,000 containment area would have prevented a legacy of contamination, Matson said: “They could have zippered up this plant so that what has happened wouldn't have happened.”

Although the plant manager said in 1969 that the company had stopped using PCBs, evidence shows that high amounts of the compounds were found in sludge in the air compressor tanks in 1995, company workers said in deposi-tions. “Well, the reality is they didn't stop using PCBs and – and the feed pond got horribly contaminated with PCBs, which created a problem in the late '90s as to what to do about it,” Matson said. Monsanto repaired the leaking feed pond, but not before it may have contaminated another area, which ultimately led to runo� into the river, plainti�s experts suggest. The mid and late 1990s is when PCB levels in oysters stopped declining, suggesting that was when additional amounts of PCBs began draining o� the plant site, said plainti�s' expert Edward Garvey, a geochemist who also studied the Hudson River. Another plainti�s' expert raised concerns about continuing pollution after recent soil samplings showed PCBs at �ve spots. “It is evident that PCBs are migrating to the Escambia River and concentrating within the depositional environments of the river,” wrote Ronald Scrudato, director of technology at Global Green Environmental, which specializes in removal of toxic materials from soil and wastewater. “The elevated soil samples collected and analyzed in September 2012 demon-strated that Ascend properties are contributing to the PCB migration to the Escambia River and Bay systems.” “It is likely that the PCBs originating near (the plant site) are the primary source of contamination to �sh in the Escambia River and upper Escambia Bay, as documented by Snyder and Roa,” wrote Garvey.

Not from us, Monsanto says

The defense team has faulted these experts, saying the PCBs found in some samplings were di�erent from the types of PCBs used by Monsanto, and that some of the higher concen-trations were found further downstream, near Plant Crist. Gulf Power o�cials were surprised to hear that claim. “We don't know of any kind of PCB discharge at Plant Crist,” said spokesman Je� Rogers. The utility made an e�ort in the 1990s to remove any traces of PCBs in equipment at the plant, and crews regularly test for hazardous chemicals, he said. Defense consultant Wayne Grip pointed out that in 1999, Gulf Power did obtain a permit to burn waste oil which may have contained PCBs, but Rogers said company engineers have shown that the amount of the compounds in the oil were so small, and were incinerated so completely, that they could not have contaminated any sediment. The defense also has o�ered what a casual observer might call hair-splitting: One section of state law allows damages to be awarded because of a pollution discharge, but only only if the contaminants came from a “terminal facility,” such as the barge dock on the northeast corner of the Monsanto plant site. Monsanto released PCBs only from an

outfall ditch a few hundred yards to the south, so therefore did not violate the law, according to a defense motion. The Monsanto lawyers also o�ered another interest-ing defense: The company couldn't have violated any state sediment pollution standards because Florida has none for PCBs. The DEP didn't establish numerical water quality standards until 1990, and it still has no real sediment standards. The agency has published only Sediment Quality Assessment Guidelines, which encourage investigations of contamination when it rises above a certain level, but do not require any action.

The lawsuit also provides a rare glimpse into Monsanto's corporate mindset in the late 1960s. Shortly after controversy over PCBs spread worldwide, but before contami-nation in Escambia Bay was widely known, Monsanto estab-lished a “PCB Committee” to discuss its options, according to an August 1969 hand-written company memo that was included in the court �les. In Pensacola, the memo notes that state o�cials had visited the nylon plant, but asked “no real searching questions...Lid probably on for the moment.”