Quality Initiative to Introduce Pediatric Venous ... · screening tool, provider education,...

Transcript of Quality Initiative to Introduce Pediatric Venous ... · screening tool, provider education,...

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Quality Initiative to Introduce Pediatric VenousThromboembolism Risk Assessment forOrthopedic and Surgery PatientsLaura H. Brower, MD,a,b Nathalie Kremer, MD,c,d Katie Meier, MD,a,b Christine Wolski, MD,a,b Molly M. McCaughey, BSN, MSN,e,f Emily McKenna, MSN, APRN, FNP,f,g

Jennifer Anadio, MA,e Emily Eismann, MS,h Erin E. Shaughnessy, MD, MSHCMa,b

A B S T R A C T BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Pediatric hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE)is costly, has high morbidity, and is often preventable. The objective of this quality-improvementeffort was to increase the percentage of general surgery and orthopedic patients $10 years of agescreened for VTE risk from 0% to 80%.

METHODS: At a freestanding children’s hospital, 2 teams worked to implement VTE risk screeningfor postoperative inpatients. The general surgery team used residents and nurse practitioners toperform screening whereas the orthopedic team initially used bedside nursing staff. Both groupsemployed multiple small tests of change. Shared key interventions included refinement of ascreening tool, provider education, mitigation of failures, and embedding the risk assessment taskinto staff workflow. The primary outcome measure, the percentage of eligible patients with acompleted VTE risk assessment, was plotted on run charts. Secondary outcome measures forscreened patients included the level of risk, the use of appropriate prophylaxis, and VTE events.

RESULTS: Median weekly percentage of general surgery patients screened for VTE risk increasedfrom 0% to 86% within 12 months, and median weekly percentage of orthopedic patientsscreened for VTE risk increased from 0% to 46% within 8 months. Among screened patients,the majority were at low or moderate risk for VTE and received prophylaxis in accordance withor beyond guideline recommendations. No screened patients developed VTE.

CONCLUSIONS: Quality-improvement methods were used to implement a VTE risk screeningprocess for postoperative patients. Using providers as screeners, as opposed to bedside nurses, led toa greater percentage of patients screened.

aDivisions of HospitalMedicine, cPediatricUrology, ePediatric

Orthopedic Surgery, andgPediatric General and

Thoracic Surgery,bDepartments of

Pediatrics, dSurgicalServices, fPatient

Services, and hMayersonCenter for Safe and

Healthy Children, Collegeof Medicine, University of

Cincinnati, Cincinnati,Ohio

www.hospitalpediatrics.orgDOI:https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0203Copyright © 2017 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

Address correspondence to Laura H. Brower, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center,3333 Burnet Ave, ML 3024, Cincinnati, OH 45229. E-mail: [email protected]

HOSPITAL PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 2154-1663; Online, 2154-1671).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Drs Brower and Kremer conceptualized and designed the study, oversaw improvement activities, and drafted the initial manuscript;Dr Meier, Dr Wolski, Ms McCaughey and Ms Anadio participated in the design of the study of the interventions for improvement;Ms McKenna and Ms Eismann participated in the design of the study of the interventions for improvement, and provided data support;Dr Shaughnessy conceptualized and designed the study, and oversaw improvement activities; and all authors reviewed and revisedthe manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

HOSPITAL PEDIATRICS Volume 7, Issue 10, October 2017 595

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) events,including deep venous thrombosis andpulmonary embolism, have becomeincreasingly recognized as a significant publichealth burden. In 2008, the US SurgeonGeneral issued a Call to Action to preventVTE,1 and in 2012, the Children’s Hospitals’Solutions for Patient Safety network identifiedVTE as a focus for harm prevention.2

The incidence of pediatric VTE is low, with1 estimate using the National HospitalDischarge Survey database at 4.9 per100 000 children per year,3 although recentevidence suggests that the incidence ofhospital-acquired VTE is increasing by up totwofold in some studies.4–6 Although rare, VTEevents have significant consequences, includingpostthrombotic syndrome, pulmonaryhypertension, and death.7–10 The development ofVTE during or related to a hospitalization alsolikely incurs greater lengths of stay, increasedcosts, and potentially recurrent hospitalization.

For patients .18 years of age, the Capriniet al11 risk assessment model is widelyaccepted as best practice. An evidence-based care guideline for VTE riskassessment and prophylaxis in patients10 to 17 years of age developed at ourinstitution was recently published.12,13

Despite guideline availability, nostandardized process existed for riskassessment. Given that key risk factorsfor VTE include altered mobility, certaintraumatic injuries, and certain orthopedicprocedures, we developed 2 quality-improvement (QI) initiatives to increase VTErisk assessment in high-risk surgicalpatients. One initiative focused on pediatricgeneral surgery patients, and the otherfocused on orthopedic patients. The shared,specific aim of these QI initiatives was toincrease the percentage of orthopedic andgeneral surgery patients who underwentVTE risk screening within 24 hours ofadmission to the hospital from 0% to 80%.We hypothesized that interventions focusedon standardization of the process for riskassessment would improve screening rates.

METHODSContext

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital MedicalCenter is a 522-bed freestanding children’s

hospital. General surgery admits patients toseveral units in the hospital, whereasorthopedic surgery admits primarily to asingle unit. The general surgery andorthopedic services are each staffed byattending surgeons, fellows, residents,and nurse practitioners (NPs). Based onprimary service request, pediatric hospitalmedicine (HM) physicians co-managemany orthopedic patients and provideconsultative services for some generalsurgery patients. Key differences betweenthe 2 initiatives are highlighted in Table 1.The general surgery team included patients10 to 17 years of age, whereas theorthopedic team included all patients.10 years of age because of the concernthat adult patients were not beingconsistently screened for VTE risk (∼10% ofeligible patients). The orthopedic teaminitially used bedside nurses to completethe risk assessments because of lessconsistent provider presence in theinpatient service as compared with thegeneral surgery team. The orthopedic teamincluded only patients in the primaryadmitting unit.

The Caprini et al11 guideline for VTE riskassessment for adults stratifies risk by thenumber of risk factors into low, moderate,higher, or highest risk. The guideline byShaughnessy and co-workers13 for VTEassessment for patients 10 to 17 years ofage similarly stratifies risk for VTE into low,moderate, or high based on the numberof risk factors present and whether thepatient has altered mobility for.48 hours.12

In both guidelines, the risk levels correlatewith the following suggested strategies forVTE prophylaxis: early ambulation, the useof mechanical prophylaxis (such assequential compression devices [SCDs]),and pharmacologic prophylaxis,respectively. Each guideline outlinescontraindications for prophylaxis use.11–13

Intervention

At our institution, QI initiatives for thebenefit of the institutions’ patients are notsubject to review and approval by theInstitutional Review Board.

Each team was multidisciplinary. Forpediatric general surgery, the team includedpediatric general surgery physicians andNPs, HM physicians, and registered nurses(RNs), and for orthopedics, the teamincluded orthopedic physicians, NPs, projectmanagers, research coordinators, and HMphysicians. Each team mapped the processfor patient admission, determined riskassessment opportunities during theadmission process, and identified keydrivers (Fig 1). The teams created a riskassessment tool based on the publishedguidelines for adolescents (ages 10–17 years)13

and adults11 (Supplemental Information).Sequential plan-do-study-act cycles wereperformed to refine the assessment tool anddevelop further interventions to improverates of screening based on the Model forImprovement.14 Successful interventions wereadjusted as needed and adopted. Althoughboth improvement teams implemented ascreening process, the general surgery groupfocused on using NPs and resident physiciansas the primary screeners, whereas theorthopedic surgery team opted for bedsidenurses as the primary screeners. Althoughthere were many reasons for these choices,geography played a central role. For generalsurgery, patients were on several floors,making the NPs and resident providers amore consistent group seeing all patients.Because orthopedic surgery patients werecohorted in 1 nursing unit, bedside nursesseemed a feasible option for the screeningpractitioners.

Study of the Intervention

Data were collected for both teams viareview of the electronic medical record

TABLE 1 Comparison Between General Surgery and Orthopedic Projects

General Surgery Orthopedics

Included patients $10 y and ,18 y of age All patients $10 y of age

Unit All inpatients on service overmultiple units

Limited to 1 primary orthopedicinpatient unit

Risk assessment performed by Residents and NPs Bedside nurses (initially)Residents and NPs (later in project)

596 BROWER et al

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

(EMR). The general surgery team collectedbaseline data during fall 2013. Eligiblepatients included those 10 to 17 years ofage admitted to the general surgeryinpatient service. The orthopedic teamcollected baseline data during spring 2014.Eligible patients included those $10 yearsof age admitted to the orthopedic inpatientservice in the primary orthopedic inpatientunit. Although, at baseline, some patientswere receiving prophylaxis for VTE (ie,SCDs), we did not count the use ofprophylaxis as having been assessed for VTErisk. We determined that successful VTErisk assessment would be defined asdocumentation of risk level per theguidelines.

Measures

The primary outcome measure for eachteam was the percentage of eligible patientswho had documentation of VTE risk level.Secondary outcome measures for screenedpatients included risk level and the use ofprophylaxis. VTE events in eligible patientswere tracked. Other data collected includedage, sex, and primary service for eligiblepatients.

Analysis

Each team used a run chart for analysis ofthe primary outcome measure. Establishedrules were used for identifying specialcause variation for run charts.15–19

Descriptive statistics were used to analyzedemographic data, VTE events, risk levelsof screened patients, and the use ofprophylaxis in screened patients.

RESULTSKey Interventions: General Surgery

The general surgery team recognized 4 keyinterventions that enabled successfulimplementation of the VTE risk assessmentprocess. The first key intervention wasrefinement of the VTE risk assessment toolbased on feedback from frontlinepractitioners. The initial introduction of thetool took place in the Same Day Surgeryarea with the assistance of the nursingstaff. This area was selected because of anexisting standardized process for evaluationand postoperative admission of generalsurgery patients. After refinement, the riskassessment tool was spread to includeadmissions from the emergency departmentand outside institutions. VTE riskassessments were completed by surgicalresident physicians and NPs for admissionsoccurring outside of Same Day Surgery.

The second key intervention was aconcerted effort to educate providersregarding the importance of VTE riskassessment.11,12 The risk assessment tooland project rationale were introduced tophysicians and then all members of thedepartment, including surgical NPs andnurses, through an educationalpresentation at a departmental meeting.Small, brightly-colored pocket cardshighlighting the risk assessment tool weredistributed to providers and were postedon computers in clinical work areas.

A third essential intervention was therecognition and mitigation of process

failures. Daily chart audits identifiedfailures, and team members (typicallythe fellow on the surgical team) provideddirect verbal feedback to responsibleproviders shortly after a failureoccurred. Because of initial high variabilitybetween providers, the team distributeda chart that documented failures perindividual providers as a visual incentiveto improve.

The final set of critical interventionsinvolved embedding key aspects of theprocess into the EMR. Because so much ofthe providers’ work is done directly in theEMR, this step helped to more reliablyincorporate the process as standard work.For example, although providers wereinitially asked to add VTE risk assessmentto their electronic notes, this processdepended on individual providersremembering to perform the task. Theteam later modified general surgicalnote templates to include an automated,mandatory VTE risk section, prompting thecompletion of VTE risk before the note couldbe signed.

To further support provider riskassessment and assist with appropriateordering of VTE prophylaxis, an electronic“VTE order set” was created and added tocommonly used sets of postoperativeorders. The VTE order set included anelectronic version of the risk assessmenttool and the associated recommendedprophylaxis. Providers could click on ahyperlink within the order set to easily referto the appropriate guideline.

Key Interventions: OrthopedicSurgery

The orthopedic team used many earlyinterventions that were similar to thegeneral surgery team. For example, the riskassessment tool was introduced andmodified based on feedback via frontlineproviders, in this case, bedside RNs. Theteam also used provider education viapresentations, handouts, and discussion inmonthly resident educational meetings.Additionally, visual reminders of the newrisk assessment process, including pocketcards and signs in unit workspaces,reinforced provider education.

FIGURE 1 Shared key driver diagram.

HOSPITAL PEDIATRICS Volume 7, Issue 10, October 2017 597

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

A distinct early intervention that provided asignificant boost in VTE assessment rateswas a daily morning huddle, which providedan opportunity for failure mitigation fromthe previous 24 hours. This huddle includedthe unit charge nurse, orthopedic NPs, andHM physicians, who would meet in the unitand identify patients eligible for riskassessment. Bedside nursing championsalso volunteered to actively identify eligiblepatients throughout the day and overnight.However, the boost in assessment ratesproved temporary despite intense effort.

After several months without significant,sustained improvement, the orthopedicteam, with input from the unit nursing staff,failure analysis, and shared learningsfrom the general surgery team, changed therisk assessment responsibility from bedsideRNs to providers (ie, physicians and NPs).This change, although requiring significanteffort from the team as they targeted a newgroup of providers with a different

workflow, ultimately proved essential tosuccessful implementation (Fig 2).

Finally, the orthopedic team adopted asimilar intervention to the general surgerygroup by incorporating EMR changes tosupport provider workflow.

Clinical Outcomes

On the general surgery team, the medianweekly percentage of eligible patientsassessed for VTE risk initially increasedfrom 0% to 82% within 4 months afterconcentrated educational efforts. The teamthen experienced a sustained rate of VTEassessment of 71%, which ultimatelyimproved to 86% after EMR documentationand order set interventions. The medianassessment rate of 86% has remainedstable over a 6-month follow-up period(Fig 2).

On the orthopedic team, during the RN riskassessment period, the median weeklypercentage of eligible patients assessed for

VTE risk increased from 0% to 13% within3 months but continued to show significantvariability without continued increase.Noting a large number of incomplete riskassessments, failure analysis revealeddifficulty with completion of riskassessment, with .50% of our failurescoming from incomplete or incorrectlycompleted risk assessments. After thechange to provider screening followed bythe implementation of changes to theEMR documentation, the median weeklypercentage of completed risk assessmentsincreased from 13% to 46% within 4 months(Fig 2).

No eligible patients were diagnosed with VTEduring the study period. Demographics andrisk levels of screened patients withprophylaxis use are presented in Table 2.The majority of screened patients werefound to be at low or moderate risk for VTE.Prophylaxis was frequently used inscreened patients, with .80% of orthopedic

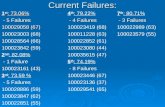

FIGURE 2 Dual run chart for primary measure: the percentage of general surgery and orthopedic patients who were screened for VTE risk.

598 BROWER et al

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

patients and 99% of general surgerypatients receiving prophylaxis in line withthe guideline recommendations or beyondguideline recommendations. For theorthopedic patients with prophylaxis beyondguideline recommendations, the majority(93%) were low-risk patients receivingSCDs.

DISCUSSION

Through using provider-based riskassessment, standardization of the riskassessment process, and embedding therisk assessment into the workflow offrontline providers, we were able toincrease the percentage of pediatricgeneral surgery inpatient adolescents andorthopedic inpatients $10 years of ageassessed for VTE risk; ultimately, thegeneral surgery team effort was moresuccessful. Contrasting the 2 effortsprovides valuable insights for futureimplementation efforts.

Interpretation

In the first phase of the orthopedic teamproject, bedside nurses were assignedto complete the risk assessment. When ourimprovement efforts were not successful,the team completed failure analysis,including eliciting feedback from nurses. Wefound that the VTE risk assessment task didnot fit well into nurses’ workflow or theirtraditional expertise; in particular, some of

the risk assessment questions fell outsidethe scope of what bedside RNs typicallyasked patients and families. Additionally, themajority of the bedside RN workflow washoused in the EMR, and the use of a paperform for risk assessment led to additionalfailures related to inability to find forms andlost forms.

In both initiatives, the creation of a riskassessment tool allowed for the translationof institutional guidelines into a usableformat for frontline providers.11,12 We thenembedded this tool into the daily workflowof NPs and physicians by making the riskassessment process part of the EMR ordersand documentation. This step providedreminders and decreased the amount oftime necessary for a provider to completethe VTE risk assessment.

However, despite efforts to increase thelevel of reliability of our interventions, suchas the use of EMR supports, our riskassessment process remained highlyhuman-dependent. Many of the orthopedicpatients who did not receive riskassessments had hospital stays of less than24 hours, for example, undergoing operativereduction of uncomplicated fracture. Thisshort time frame meant that many patientswere discharged before triggering processchecks, such as daily huddles and NP orhospitalist rounds. We believe this

dependency on individuals to ensure taskcompletion is the primary reason our ratesof implementation by the orthopedic teamremained lower than the goal.

Overall, despite the orthopedic teamadopting several best practices from thesurgery team, it is striking that the surgerygroup achieved and sustained a muchhigher rate of success. We believe a uniquefeature of our surgery care team thatenabled this performance was a high levelof redundancy, with several layers ofproviders ensuring that risk assessmentwas complete. For example, whereasresidents and NPs were primarilyresponsible for the risk assessment, asurgery fellow rounding on all patientsroutinely asked about VTE risk, providinganother check on the process. In contrast,the orthopedic team did not have acorollary to the surgery fellow and did nothave a consistent daily presence of NPs tosupport the process because of anunforeseen staffing shortage.

Reflecting on these differences, we feel thata consistent provider workforce isimportant to support a standardizedprocess, and we plan to regroup the effortonce a more stable NP staff is achieved inorthopedic surgery. Beyond that, we believethat future interventions must use a human-factors engineering approach to makethe completion of risk assessment a defaultoperation (for example, including it as partof standard admission work in the EMR)and thus mitigate the impact of providerfallibility. A final factor that likelycontributed to the surgical team’s successwas a competitive culture; the surgery teampublicly posted individual performance,which proved to be a powerful motivator.The orthopedic team did not feel such anintervention would be effective in its culture.

Secondary Outcomes

We also found that a large percentageof patients admitted to the pediatric generalsurgery and orthopedic services were atlow to moderate risk for VTE. Many low-riskorthopedics patients received SCDs, whichwe suspect is related to a previous practiceof placing SCDs on many postoperativepatients. Because of the low incidence ofpediatric VTE, no eligible patients developed

TABLE 2 Demographic Data, Risk Levels, and the Use of Prophylaxis

General Surgerya Orthopedics

Eligible patients, n 603 506

Age, y, mean 6 SD 14 6 2.3 14 6 3.5

Boys, n (%) 331 (54.9) 276 (54.5)

Eligible patients with completed risk assessment, n (%) 487 (80.8) 135 (26.7)

Risk level

Low, n (%) 404 (83.0) 63 (46.7)

Moderate, n (%) 71 (14.6) 53 (39.3)

High, n (%) 12 (2.4) 19 (14.0)

Prophylaxis useb

Same as risk level, n (%) 475 (97.5) 83 (61.5)

More than risk level, n (%) 7 (1.4) 30 (22.2)

Less than risk level, n (%) 5 (1.0) 22 (16.3)

a The data for general surgery patients are from a 6-month sample in 2013.b Based on recommendations in evidence-based care guidelines. For example, “same as risk level” wouldbe a patient who is at moderate risk who received SCDs; “more than risk level” would be if that patientreceived enoxaparin; and “less than risk level” would be if the patient only received physical therapy orearly ambulation.

HOSPITAL PEDIATRICS Volume 7, Issue 10, October 2017 599

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

VTE during our baseline or study period. Wewere thus unable to measure the effect ofincreased risk screening on the incidenceof VTE.

Other studies have described workimplementing risk assessment andprophylaxis strategies for VTE. Raffini et al20

described a successful quality initiative toincrease the rate of guideline-compliantprophylaxis for VTE, as opposed to ourproject, which focused on risk assessment.The Raffini study population wascomparable, although their younger limitfor screening was 14 years of age. 20 Incontrast to our findings, this group reportedsuccessful implementation of riskassessment as part of the RN intakeprocess.

Mahajerin et al21 described the developmentand implementation of a local guideline forVTE risk assessment and prophylaxis at apediatric tertiary care center. This group ofresearchers aimed to screen all eligibleadmissions ,12 years of age to theirinstitution. Through the use of a screeningtool embedded in the EMR, they increasedthe percentage of eligible patients who werescreened for VTE risk.

A final study, by Hanson et al,22 describedthe results of VTE prophylaxis guidelineimplementation for a specific population,pediatric patients with trauma admitted tothe ICU. They reported successful guidelineimplementation with a 65% decrease indetected VTE in the study population, butthey did not detail the process ofimplementation.

Limitations

Although we included 2 differentpopulations of pediatric surgical patientsand found several interventions that wereimportant for both populations, our findingsas to key interventions may not apply asbroadly to other types of patients, such asgeneral medical or other subspecialtypediatric patients. In addition, because bothimprovement teams worked at a single,large, freestanding pediatric hospital, ourinterventions may not translate equally toother settings.

Finally, this study was not designed toassess the impact on rates of VTE. The

overall rate of VTE is low at our hospital,and the populations included in thisinitiative had relatively low rates of high-riskassessments. Future implementation effortsat our institution will target patients athigh risk.

CONCLUSIONS

The implementation of VTE risk assessmentin pediatric surgical and orthopedicpatients required standardizing theassessment process and embedding itwithin the workflow of providers,particularly by using EMR supports. Ingeneral, we found more success by usingphysician and NPs rather than bedsidenurses to evaluate patients for VTE riskfactors. Future researchers will seek toapply and expand these learnings to otherhigh-risk populations and use human-factors engineering to increase thereliability of the process.

REFERENCES

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US);National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute(US). The Surgeon General’s Call toAction to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosisand Pulmonary Embolism. Rockville, MD:Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Accessed November20, 2014

2. Children’s Hospitals’ Solutions forPatient Safety. SPS recommendedbundles. 2013. Available at: www.solutionsforpatientsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/SPS-Recommended-Bundles.pdf. Accessed December 22,2014

3. Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Incidence ofvenous thromboembolism in infants andchildren: data from the National HospitalDischarge Survey. J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):563–565

4. Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C.Dramatic increase in venousthromboembolism in children’s hospitalsin the United States from 2001 to2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1001–1008

5. Boulet SL, Grosse SD, Thornburg CD,Yusuf H, Tsai J, Hooper WC. Trends in

venous thromboembolism-relatedhospitalizations, 1994-2009. Pediatrics.2012;130(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/130/4/e812

6. Sandoval JA, Sheehan MP, Stonerock CE,Shafique S, Rescorla FJ, Dalsing MC.Incidence, risk factors, and treatmentpatterns for deep venous thrombosis inhospitalized children: an increasingpopulation at risk. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(4):837–843

7. Andrew M, David M, Adams M, et al.Venous thromboembolic complications(VTE) in children: first analyses of theCanadian registry of VTE. Blood. 1994;83(5):1251–1257

8. Biss TT, Brandão LR, Kahr WH, Chan AK,Williams S. Clinical features andoutcome of pulmonary embolism inchildren. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(5):808–818

9. Goldenberg NA, Donadini MP, Kahn SR,et al. Post-thrombotic syndrome inchildren: a systematic review offrequency of occurrence, validity ofoutcome measures, and prognosticfactors. Haematologica. 2010;95(11):1952–1959

10. Monagle P, Adams M, Mahoney M, et al.Outcome of pediatric thromboembolicdisease: a report from the Canadianchildhood thrombophilia registry.Pediatr Res. 2000;47(6):763–766

11. Caprini JA, Arcelus JI, Reyna JJ. Effectiverisk stratification of surgical andnonsurgical patients for venousthromboembolic disease. SeminHematol. 2001;38(2 suppl 5):12–19

12. Multidisciplinary VTE Prophylaxis BEStTeam; Cincinnati Children’s HospitalMedical Center. Best evidence statementVenous Thromboembolism (VTE)prophylaxis in children and adolescents.Available at: www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/bests/. 1–15. AccessedJanuary 27, 2014

13. Meier KA, Clark E, Tarango C, Chima RS,Shaughnessy E. Venousthromboembolism in hospitalized

600 BROWER et al

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

adolescents: an approach to riskassessment and prophylaxis. HospPediatr. 2015;5(1):44–51

14. Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, NolanTW, Norman CL, Provost LP. TheImprovement Guide: A PracticalApproach to Enhancing OrganizationalPerformance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA:Jossey-Bass; 2009

15. Carey RG. How do you know that yourcare is improving? Part I: basic conceptsin statistical thinking. J Ambul CareManage. 2002;25(1):80–87

16. Provost LP, Murray SK. The Health CareData Guide: Learning From Data forImprovement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011

17. Benneyan JC. Use and interpretation ofstatistical quality control charts. Int JQual Health Care. 1998;10(1):69–73

18. Benneyan JC. Statistical quality controlmethods in infection control andhospital epidemiology, part I:introduction and basic theory. InfectControl Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19(3):194–214

19. Benneyan JC. Statistical quality controlmethods in infection control andhospital epidemiology, part II: chart use,statistical properties, and researchissues. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.1998;19(4):265–283

20. Raffini L, Trimarchi T, Beliveau J, Davis D.Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric

hospital: a patient-safety and quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/5/e1326

21. Mahajerin A, Webber EC, Morris J, TaylorK, Saysana M. Development andimplementation results of a venousthromboembolism prophylaxis guidelinein a tertiary care pediatric hospital.Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(12):630–636

22. Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Arca MJ, et al.Effectiveness of clinical guidelines fordeep vein thrombosis prophylaxis inreducing the incidence of venousthromboembolism in critically illchildren after trauma. J Trauma AcuteCare Surg. 2012;72(5):1292–1297

HOSPITAL PEDIATRICS Volume 7, Issue 10, October 2017 601

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0203 originally published online September 12, 2017; 2017;7;595Hospital Pediatrics

ShaughnessyMcCaughey, Emily McKenna, Jennifer Anadio, Emily Eismann and Erin E.

Laura H. Brower, Nathalie Kremer, Katie Meier, Christine Wolski, Molly M.Assessment for Orthopedic and Surgery Patients

Quality Initiative to Introduce Pediatric Venous Thromboembolism Risk

ServicesUpdated Information &

http://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/7/10/595including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Supplementary Material

2016-0203.DCSupplementalhttp://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2017/09/09/hpeds.Supplementary material can be found at:

Referenceshttp://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/7/10/595#BIBLThis article cites 15 articles, 5 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.hosppeds.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/safety_subSafetyrovement_subhttp://www.hosppeds.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/quality_impQuality Improvementon:practice_management_subhttp://www.hosppeds.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administratiAdministration/Practice Managementfollowing collection(s): This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

mlhttp://www.hosppeds.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtin its entirety can be found online at: Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprintshttp://www.hosppeds.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtmlInformation about ordering reprints can be found online:

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from

DOI: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0203 originally published online September 12, 2017; 2017;7;595Hospital Pediatrics

ShaughnessyMcCaughey, Emily McKenna, Jennifer Anadio, Emily Eismann and Erin E.

Laura H. Brower, Nathalie Kremer, Katie Meier, Christine Wolski, Molly M.Assessment for Orthopedic and Surgery Patients

Quality Initiative to Introduce Pediatric Venous Thromboembolism Risk

http://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/7/10/595located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

http://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2017/09/09/hpeds.2016-0203.DCSupplementalData Supplement at:

Print ISSN: 1073-0397. Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2017 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca,publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. Hospital Pediatrics is owned, Hospital Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

by guest on January 15, 2021www.aappublications.org/newsDownloaded from