Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit - University of Toronto · This paper examines the phenomenon of...

Transcript of Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit - University of Toronto · This paper examines the phenomenon of...

This article was downloaded by: [142.1.14.87] On: 20 December 2013, At: 14:09Publisher: Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS)INFORMS is located in Maryland, USA

Marketing Science

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://pubsonline.informs.org

Profit-Increasing Consumer ExitAmit Pazgal, David Soberman, Raphael Thomadsen

To cite this article:Amit Pazgal, David Soberman, Raphael Thomadsen (2013) Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit. Marketing Science 32(6):998-1008.http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2013.0804

Full terms and conditions of use: http://pubsonline.informs.org/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used only for the purposes of research, teaching, and/or private study. Commercial useor systematic downloading (by robots or other automatic processes) is prohibited without explicit Publisherapproval. For more information, contact [email protected].

The Publisher does not warrant or guarantee the article’s accuracy, completeness, merchantability, fitnessfor a particular purpose, or non-infringement. Descriptions of, or references to, products or publications, orinclusion of an advertisement in this article, neither constitutes nor implies a guarantee, endorsement, orsupport of claims made of that product, publication, or service.

Copyright © 2013, INFORMS

Please scroll down for article—it is on subsequent pages

INFORMS is the largest professional society in the world for professionals in the fields of operations research, managementscience, and analytics.For more information on INFORMS, its publications, membership, or meetings visit http://www.informs.org

Vol. 32, No. 6, November–December 2013, pp. 998–1008ISSN 0732-2399 (print) � ISSN 1526-548X (online) http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2013.0804

© 2013 INFORMS

Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit

Amit PazgalJesse H. Jones School of Management, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77005, [email protected]

David SobermanRotman School of Management, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3E6, Canada,

Raphael ThomadsenOlin Business School, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, [email protected]

This paper examines the phenomenon of profit-increasing consumer exit and the related phenomenon ofprofit-decreasing consumer entry. We demonstrate that firms can be better off in shrinking markets and

worse off in growing markets, even in the absence of competitive entry or exit. Specifically, firms may benefitif a segment of consumers who are relatively indifferent about consuming any product in the category leavethe market. Profits can increase for all firms even if the exiting consumers have strong preferences for only oneof the products in the market. In shrinking markets, it is reasonable to assume that the people who are likelyto exit the market first are people who are “least committed” to the category. In particular, people who are theleast satisfied with the existing offers are the most likely to change their behavior by finding an alternative oradopting a new technology. Similarly, in growing markets, consumers who enter the market late are generallythe least committed to the category. Such exiting can relax the competitive pressure between firms and leadto increased profitability. Our findings provide an explanation for profit growth that has been observed inproduct industries exhibiting slow and predictable declines over time, including vacuum tubes, cigarettes, andsoft drinks.

Key words : competitive analysis; analytic models; game theory; market evolutionHistory : Received: March 31, 2012; accepted: May 12, 2013; Preyas Desai served as the editor-in-chief and Eitan

Muller served as associate editor for this article. Published online in Articles in Advance September 5, 2013.

1. IntroductionWould a manager rather compete in a growing mar-ket or a shrinking market? Conventional wisdom sug-gests that growing markets are more attractive (Kotlerand Keller 2012). This is underlined by managerialtools such as the Boston Consulting Grid, which usesmarket growth as a proxy for market attractivenesswhen considering investments (Lilien et al. 1992).This conventional wisdom has been challenged byresearchers who say that firms could be worse off ingrowing markets if such growth is associated withlarge levels of entry that lead to intense competi-tion. For example, the costs of research and devel-opment, distribution systems, and awareness systemslimit the profitability of new entrants in growing mar-kets (Gatignon and Soberman 2002).

What happens, however, when there is no entryor exit by rival firms? Can firms be more profitablein a shrinking market and less profitable in a grow-ing one? We show that these events are quite possi-ble with two uncontroversial assumptions: In growingmarkets, consumers who enter the market late are thepeople who are “least committed” to the category.

Similarly, in shrinking markets, consumers who aremost likely to exit the market first are people who areleast committed to the category.

Consider the cigarette market in the United States.Since 1982, when the cigarette market peaked at 640billion pieces, it has declined significantly. Today, themarket is estimated to be less than 400 billion pieces,a decrease of more than 35% in terms of volume(Womach 2003). Explanations for this decline abound.Studies have demonstrated that tobacco exhibits char-acteristics similar to other categories of consumergoods; important factors that have had a significanteffect on overall consumption are (a) average pric-ing and (b) per-capita income (Wilcox and Vacker1992). In addition, the health effects of smoking haveundoubtedly contributed to reduced smoking in theUnited States. Despite a gradual and predictabledecline in cigarette sales beginning in 1982, the profitsof domestic cigarette manufacturers exhibited signifi-cant growth through 1990 (Bauder 1984, Gordon 1985,Wiggins 1985, Ticer 1986, Yankeelov 1986).1

1 It is important to note that the important lawsuits undertaken byvarious state governments and class actions did not start until the

998

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer ExitMarketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS 999

A key question is, why did the profits of cigarettemanufacturers hold up so well in a context ofdeclining sales and reduced popularity of smoking?2

To answer this question, we first consider the type ofpeople who stopped buying and consuming cigarettesover the course of the decline. We abstract awayfrom the natural evolution of tobacco consumers,where people start buying cigarettes in their teensand stop buying later in life, and focus our attentionon the fraction of consumers who stopped smokingearly or quit smoking. In general, these were peoplewho wanted to reduce their tar and nicotine intake.Many ex-smokers smoked low-tar cigarettes beforethey quit. They may have enjoyed smoking, but theywere perhaps unwilling to accept the level of riskassociated with tobacco consumption.

The reality is that tobacco companies were unableto (or chose not to) develop tar-free cigarettes. Theexistence of a segment that seeks the satisfaction ofsmoking without the inherent risk is underlined bythe recent development of electronic cigarettes, whichdo not deliver tar (Zezima 2009, Keeley 2012). Theseobservations are further supported by research andsurveys that show that people who were (and are)most likely to quit are smokers of low-tar and nicotinecigarettes (Kozlowski et al. 1999, Kelbsch et al. 2005).

In our model, we show that these are preciselythe conditions associated with increased profits ina shrinking market. It is also important to notethat the U.S. tobacco market was dominated by sixmajor cigarette manufacturers in 1982: this marketstructure remained stable until 1994, when Brown &Williamson merged with American Tobacco.3 Thus,it is difficult to explain increased profitability bychanges in market structure or concentration. In a nut-shell, tobacco consumers who were leaving the mar-ket were less committed to the category. Their relativepreference for the products on the market were small(none of the products offered what these consumerswanted: a product that delivered flavor and satisfac-tion without the perceived risk). It is straightforward

early 1990s. Although these lawsuits no doubt reduced the profitsof the tobacco companies, we restrict our attention to the “pre-litigation” period. There were private lawsuits launched againsttobacco companies prior to 1990, but generally, these were suc-cessfully defended or had a negligible impact on tobacco companyprofits.2 The penetration of smoking reached a peak in the 1950s at wellover 40% of the adult population. Penetration has declined to cur-rently less than 25% of the adult population (see http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0762370.html, accessed July 25, 2013).3 Although Big Tobacco was often referred to as the Big Seven(Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson, Lorillard,Liggett & Myers, American Tobacco, and United States Tobacco),United States Tobacco was primarily a manufacturer of smokelesstobacco.

to see how such consumers might exacerbate compe-tition between firms.

Other examples of market decline coupled withprofit growth come from the carbonated beveragemarket and vacuum tubes industries. The per-capitaconsumption of soda declined 16% between 1998 and2011, reflecting increased concerns about obesity: sug-ary soft drinks account for a large fraction of the calo-ries consumed in the average American’s diet (Strom2012). This has led to a decline in overall volume ofapproximately 3.1% over the 13-year period.4 Never-theless, beverage companies have been making moremoney on carbonated soft drinks by raising pricesand forcing die-hard drinkers to pay more to feedtheir sugar habit. In fact, revenue from carbonatedsoft drinks reached a record high of $75.2 billion in2011 (Strom 2012).5

The production of vacuum tubes in the UnitedStates stopped sometime in the 1980s after decadesof market decline.6 As noted in Harrigan and Porter(1983), the discovery of the transistor in the late1940s meant that vacuum tubes were a technolog-ical anachronism; pundits predicted that vacuumtubes would disappear by the 1970s. Despite thesepredictions, the decline stage for vacuum tubeslasted more than 20 years. Throughout the 1960s,manufacturers maintained impressive profitability byreducing volume and focusing on price-insensitivedemand associated with replacement tubes and mili-tary applications.

In these three examples, there are three commonal-ities worth highlighting. First, the decline of the cat-egory was both gradual and predictable. Second, thedecline was driven by the departure of noncommittedcategory participants who stopped using the product(as in the case of cigarettes), switched to an alterna-tive without “negative baggage” (in the soda case,switching to diet soft drinks, water, or fruit juices),or adopted an alternative technology (in the vacuumtubes case, adopting transistors and solid state elec-tronics). Third, and finally, the firms responded byraising prices for customers who remained in themarket.

Our objective is to show how these conditions canlead to profit-increasing consumer exit. Moreover, wedemonstrate that this phenomenon is the expectedoutcome in a model where the firms compete vig-orously with each other. That is, the prediction that

4 The overall decline in volume is obtained by multiplying the per-capita decline in volume by the percentage increase in the U.S.population over the same 13-year period (12.7%) according to U.S.Census data.5 We thank the associate editor for suggesting this example.6 As of 2005, there were still manufacturers of vacuum tubes inChina and Russia.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit1000 Marketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS

incumbents can realize profit growth in decliningmarkets does not rely on any form of collusion orcoordination between the firms.

Understanding the possibility and causes of profit-increasing consumer exit has several important impli-cations for managers. For example, knowing that exitsby customers who do not easily switch between prod-ucts can increase profits. This provides a new contextfor managers to better forecast how their sales, prices,and profits will evolve over time. Furthermore, ourresults run counter to the conventional wisdom thatmanagers should restrict their investments to growingindustries. Rather, in the examples we provided, theprofit-increasing decline takes a long time to play out.Thus, in some conditions, firms in declining indus-tries may want to reinvest in their factories or signlong-term leases if such leases provide better terms.Our results also have implications for advertising andconsumer relationship management (CRM): managersin shrinking industries may be tempted to adver-tise and create loyalty programs aimed at retainingcustomers who are leaving the market. Our resultssuggest this strategy may be ill-advised—profits canincrease when less committed customers leave themarket as long as strong relationships are maintainedwith core consumers in the category.

It is also useful to underline the flip side of profit-increasing consumer exit: profit-decreasing consumerentry. This phenomenon can occur when the growthof a market is both gradual and driven by “doubters”who finally enter the category. A prototypical exam-ple of this phenomenon comes from the market forflat-screen televisions. From 2008 to 2009, unit salesin the U.S. television market rose by 2%. Despite thisincrease in volume, revenues dropped by 7%, drivenprimarily by an approximately 8% decline in prices.7

Although there are several factors that could accountfor lower average prices, a key finding was that televi-sions were increasingly being sold to less affluent andmore price-sensitive customers. In 2009, Sony’s man-agement concluded that the decreased revenues—andprofits8—in their electronics division occurred as aresult of intensified price competition, among otherfactors, despite higher unit sales.9 Gregg Richard,president of the prominent retailer P.C. Richard &Son, noted that they were “selling more TVs, moreunits, at lower retail prices,” as reported in the NewYork Times (Martin 2011). The contrast is even morestark for flat-screen TV sales in China: sales grew 70%comparing the first quarters of 2008 and 2009, but

7 See NPD DisplaySearch (2010). Kono (2011) provides a similardescription in the Japanese market for later years.8 Thus, the price decreases reflected thinner margins, not just lowercosts from learning by doing.9 See p. 3 of Sony (2009a). Unit sales are taken from Sony (2009b).

revenues increased by only 3% in the same period,leading to profit declines for manufacturers of up to90% (Xing 2009). We posit that similar effects occur intechnological industries when early movers are lessprice-sensitive than late adopters (such as Rogers’early and late majority). In many of these industries,prices fall and total profits are lower despite highersales. However, these same industries experience alearning curve where marginal costs fall as well, mak-ing it hard to tease out how much of the price cutis due to better technology and how much is due tointensified competition.10 In the following section, webriefly review the related literature.

2. Literature ReviewThe literature related to profit-increasing consumerexit is sparse because the majority of work that exam-ines decision making in shrinking markets is focusedon how to minimize damage and not on how profitscan increase (Harrigan and Porter 1983, Hague 1985).However, there are three papers that relate directly tothe ideas we investigate.

In Desai (2001), two firms compete for two seg-ments of consumers with product lines targeted bysegment. One segment (the “high” segment) has ahigh preference for quality and is sensitive to the dif-ference between products, and the other is less so(the “low” segment). The author finds that the com-peting firms often reduce the quality of the productsdesigned for the low segment so as to minimize canni-balization. The creation of low-quality line extensionsreduces the incentive that firms have to reduce theprice on high-quality products by siphoning the lowsegment to a lower-priced, lower-quality alternative.This work points to the value that can be created byeliminating price-sensitive consumers from the bas-ket of potential demand for a product. However, it isimportant to note that the value of the strategy high-lighted by Desai also entails firms earning significantprofit on the products being sold to the low segment.

Using a similar model, Coughlan and Soberman(2005) find that competing firms can increase profitsby removing price-sensitive switchers from a primarymarket with outlet malls. Price-insensitive shoppers(who remain in the primary market) are assumed toplace high value on in-store service, whereas price-sensitive shoppers (who are attracted to the outletmall) place no value on in-store service. Similar to themodel of Desai (2001), this model points to the valuethat firms can capture by removing “bad consumers”from a market. The key mechanism that allows seg-mentation to work in this model is the difference

10 Liu (2010) demonstrates that firms set early prices in ways tosubsidize the learning that they anticipate will occur, thus also loos-ening the link between prices and the learning curve.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer ExitMarketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS 1001

between segments in terms of their appreciation of in-store service; without this difference, self-selection bythe segments would not be possible.

Finally, Ishibashi and Matsushima (2009) proposea model that is similar in spirit to the two mod-els discussed above: there are two segments, onewith high preference for quality and high sensitiv-ity to product differences and the other with lowpreference for quality and less sensitivity to prod-uct differences. A low-quality entrant draws all theprice-sensitive consumers away from two incum-bents, and the authors find conditions where theincumbents earn higher profits by serving only theprice-insensitive consumers that remain.

Although none of this work deals explicitly withthe topic of consumer exit (or market shrinkage), itis straightforward to see how it relates to our topic.The contribution of our analysis is threefold. First, weshow that two dimensions of heterogeneity are notneeded for consumer exit to be profit enhancing.11

We demonstrate the phenomenon in a model wherethe only dimension of heterogeneity is horizontal dif-ferentiation. Second, we demonstrate that profits canincrease for both firms even when the customers thatexit from the market consider only consuming fromone of the firms (versus choosing the outside option).For example, a firm’s profits can increase even if theonly consumers that exit are those that are essentiallyloyal to its product. This contrasts with the above-mentioned models, where the market segment that isremoved is one that is hotly contested by both firms.

We now move to our model and consider a marketwhere there is but one dimension of heterogene-ity: horizontal differentiation. Our focus is on under-standing how consumer exit affects profitability. Asnoted earlier, our model is based on exits by con-sumers who are the most likely to exit once a marketstarts declining.

3. Exit by Consumers at theEdge of the Market

Our base model is a Hotelling market with two firmsthat are exogenously located at internal points on thelinear market. The objective to explain how the depar-ture of less committed consumers (i.e., consumerswho realize less surplus from consumption than con-sumers who are central) can lead to higher profits forcompeting firms. First, we analyze a situation wherethe departure of consumers who are less committed tothe market occurs symmetrically. We then present an

11 Desai (2001), Coughlan and Soberman (2005), and Ishibashiand Matsushima (2009) all assume two dimensions of hetero-geneity: transportation costs and a willingness to pay for quality(or service).

asymmetrical version of the model that more closelyreflects the dynamics of the tobacco and carbonatedsoft drink markets discussed in §1.

Consumers are uniformly distributed along the linewith a density of 1. We assume that consumer i’sutility from buying and consuming the product fromfirm j can be represented as

Uij = V − pj − dij1 (1)

where pj is the price charged by firm j and dij isthe distance between consumer i and the location offirm j .12 Consumers can decide not to buy from eitherfirm, in which case they consume only an outsidegood and earn a normalized utility of zero.

We assume that firms compete in prices and haveconstant and equal marginal costs, so profits for eachfirm are equal to 4pj − c5qj , where qj is the quantitysold. Without loss of generality, we set c = 0, with theimplication that p represents the absolute markup onthe product (i.e., the difference between the price andmarginal cost).

Finally, we assume that the firms are located inter-nally, away from the edge of the market, and that Vis small enough such that the market is uncoveredfor some locations (i.e., there are consumers in themarket who find that consuming the outside good ispreferable to buying either of the existing products).In particular, if the distance between the firms is 2D,we focus our attention on a market where 7

3D ≤ V ≤13 47 + 5

√105D. We further assume that the firms are

located at least a distance of 35V −

25D from the edges

of the market (before consumer exit). The basis forthese conditions is explained in §A.2 in the appendix.

One limitation of our analysis is that we treat thelocations of firms as being set exogenously. Althoughthe locations do not reflect the equilibrium outcomeof a location-then-price game, there are many reasonswhy firms might locate internally. For example, thefirms could have been initially located at optimal loca-tions when the market was new, and then the marketmight have grown around them (and moving costsmight have prevented the firms from changing theirlocation).13 Consistent with the lifecycle events notedin §1, our model is designed to represent marketsthat have just started contracting. Alternatively, firmsare sometimes limited by technology. Thus, they maywant to locate closer to the edges of the market butwould be unable to produce products at that location.

12 Note that Equation (1) is equivalent to U = v−�P −�d under thenormalization V = v/� and p = �P/�.13 We prove that there exist conditions under which the locations ofthe firms in Theorem 1 below could be chosen if the market weresmaller and the firms did not anticipate growth that leads to theex ante scenario presented in Theorem 1. Details are available fromthe authors upon request.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit1002 Marketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS

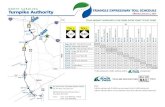

Figure 1 Removing Consumers Near the Edge (K and Farther) from Firms

Firm 1 Firm 2

These consumersexit

These consumersexit

K K

For example, cigarette companies sought to producetar-free cigarettes, but they were unable to do so.Finally, it is possible that firms do not fully know thestate of demand when they enter a market; a lot ofongoing marketing research today is devoted to mea-suring consumer preferences.

Under these assumptions, the solution to thefirst-order pricing conditions (before consumer exit)implies an equilibrium where the firms choose pricesequal to 2

5 4V +D5 and earn profits of 625 4V +D52. Note

that consumers at the edges of the market do not con-sume either product because they obtain a negativesurplus from buying. Instead, they purchase the out-side good and obtain a utility of zero.

We now consider whether profits can increase ifconsumers who are near the edge of the market leave(or exit) the category. Specifically, we consider whathappens to firm profits if consumers located a dis-tance K and farther from the firms (toward the outeredges of the market) leave. Figure 1 illustrates thissituation. We make two comparisons: (1) the rangeof K where profits after consumers exit the marketare higher than the profits before they exit and (2)the range of K where incrementally more exiting (i.e.,an incrementally smaller K) leads to greater profit.The first is a before-and-after comparison; the secondlooks at the derivative of profit with respect to K.

Theorem 1 (Exit from Both Ends of the Mar-ket). Profits increase for both firms if all consumerslocated at a distance greater than K toward the edge( from each of the firms) leave the market for any K ∈

4max842V − 3D5/51V − 4D91 43V − 2D5/55. Further-more, d�/dK < 0 after exit (that is, profits increase asmore consumers exit the market) for K ∈ 44V − D5/2143V − 2D5/55.

The proofs to the theorems are in §A.1 of theappendix. The intuition behind Theorem 1 is thatconsumer exit acts as a commitment device for thefirms to charge high prices. In the first period, firmscompete relatively intensively on price, since cuts inprices attract customers near the edge of the marketwho would otherwise consume the outside good aswell as customers from the center of the market whowould otherwise consume from the competing firm.The optimal price represents the point where the gainthat an increase in price has on profit margins exactlybalances the loss of consumers from both the edge

and the center of the market. After consumers leave,the benefit of higher margins from increased prices isrealized from all remaining customers, but the frac-tion of consumers the firm loses when it increasesprices is less because now the firm does not lose anycustomers toward the edge of the market. This meansthat at first-period prices, the benefit of higher priceson margins outweighs the loss from serving fewercustomers. Ultimately, the firms raise prices after theconsumer exit to V −K such that the most distant con-sumers remaining in the market obtain exactly zeroutility from the closest firm.14 At this point, any fur-ther increase in prices would lead to losing customersboth in the center of the market and at the edge of themarket, so there is a kink point in the demand curveat V −K.

Of course, increasing prices does not automaticallyimply increasing profits. Profits only increase as aresult of higher prices when the price increase morethan offsets the decrease in sales. To see that anincrease in price alone is not enough to guarantee thatprofits increase, consider a monopolist facing a marketwith exiting consumers at its edges. The monopolistwould raise its prices. However, the monopolist’s prof-its must decrease with consumer exit since it alwayshad the option of charging a higher price prior to mar-ket decline and serving fewer customers. Under com-petition, things are different. If a firm raises its price,its competitor’s best response would be to raise itsprice as well, resulting in higher profits for both. Theproblem is that the focal firm cannot commit to thishigh price because the consumers at the edge are stillthere, and once the competitor raises its price, it has anincentive to increase its profit by reducing its price tocapture these consumers’ business. Thus, the mecha-nism behind profit-increasing customer exit is that theconsumer exit decreases a firm’s incentive to undercutits rival, and the rival, recognizing this, will in turnincrease its price since the best response to a higherprice is an even higher price.

The upper bound for K in Theorem 1, 43V − 2D5/5,reflects the marginal consumer for each firm prior toconsumers leaving the market.15 Thus, profits increase

14 Note that a marginal decrease in K would increase prices evenmore, as the price needed to provide consumers at the new edgeof the market zero surplus would be higher.15 Consumers more distant from the firms than 43V 5/5 − 42D5/5can leave the market but have no effect on firms’ profits because

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer ExitMarketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS 1003

Figure 2 Removing Consumers from Only One Side of the Market

Firm 1 Firm 2

These consumersexit

K

as a small number of the consumers “served” farthestfrom the firm exit the market.16 The lower bound on Kreflects that there is a limit on how many consumerscan exit such that firm profits increase. It makes intu-itive sense that at some point, the increased marginthat can be made on existing die-hard consumers can-not offset the loss caused by high levels of marketshrinkage. Note that prices continue to rise with con-sumer exit even if K < 4V −D5/2, reinforcing the ideathat increases in equilibrium prices with consumerexit are not “sufficient” for profits to increase.

Theorem 1 refers to a situation where consumersexit from both edges of the market. We now move toTheorem 2, which addresses a situation where con-sumers exit from just one edge of the market. Thescenario associated with Theorem 2 is illustrated inFigure 2.

If one thinks of the Hotelling continuum as repre-senting tar and nicotine levels (in the case of tobacco)or calories or sugar content (in the case of carbon-ated soft drinks), Theorem 2 is a closer depiction ofthe dynamics described in §1. This is because in thetobacco market, consumers who wanted less tar andnicotine were the most likely to exit the category. Sim-ilarly, in the carbonated soft drink market, the con-sumers who are most likely to exit the category arethose who are looking for significantly less sugar andcalories.

Theorem 2 (Exit from Only One Side of theMarket). Profits increase for both firms if all consumerslocated at a distance greater than K toward the edge ofthe market from one of the firms exit the market for anyK ∈ 4449V − 36D5/851 43V − 2D5/55.

As in Theorem 1, Firm 1 increases its price from25 4V +D5 to V − K, the price at which the consumerat a distance K from Firm 1 toward the edge of themarket receives zero utility. Firm 1 will commit to thisprice for a wide range of prices from Firm 2 sincethis price forms a kink point in Firm 1’s demand

consumers at such locations purchase the outside good prior toconsumer exit.16 In this model, profits increase with the exit of a small number ofrelatively uncommitted consumers, but other models may requirethat a minimum number of consumers exit before such exitingleads to profit increases. We discuss such a model, where con-sumers have heterogeneous sensitivities to product differentiation,in §A.2 in the appendix.

curve. If Firm 1 charges a higher price, it would loseconsumers both toward the edge of the market andin between the two firms, whereas if Firm 1 chargesa lower price, it does not gain additional consumerstoward the edge of the market. Firm 2 knows thatFirm 1 will charge a higher price, and because pricesare strategic complements, it also increases its price(even though its direct incentives have not changed).Ultimately, Firm 2 benefits because Firm 1 chargesa higher price. Firm 1 is also better off—despiteit being the only firm to lose customers—becauseFirm 2’s higher prices allow Firm 1 to increase itsprice enough to offset the lost volume. Thus, Firm 1’sprofits increase from the consumer exit because theexit acts as a commitment device for Firm 1 to keepprices high, softening the competition it faces.

It is possible that Theorem 2 better represents thecigarette market because there are two componentsthat quitters are trying to avoid: tar and nicotine.However, the measured tar and nicotine deliveries ofcigarettes tend to be highly correlated. In any event,as long as one accepts that less committed consumers(those whose preferences are relatively distant fromthe products offered) are the ones exiting the mar-ket, the model provides a cogent explanation for whyprofits might increase in a context of a gradual marketdecline (at least in the first few years after the declinestarts).17

Note that consumers who leave the market are theconsumers who have the lowest willingness to pay forthe products in the market. This explains why firmprofits increase even though market volume drops.Since consumer entry is the opposite of consumerexit, it is straightforward to show the inverse result:profits can decrease in a market where there is con-sumer entry if the entry occurs primarily among con-sumers who have a low willingness to pay for theproducts. Thus, Theorems 1 and 2 are also informa-tive of sufficient conditions for market expansion todecrease profits. If the markets initially extend onlya distance K from the firms, and then consumersenter to fill in the market up to a distance morethan 43V 5/5 − 42D5/5 from the firm, profits will sub-sequently decrease with entry.

17 As an example supporting this assumption, a 1976 advertisementfor True cigarettes (a low-tar brand) declared, “Considering all I’dheard, I decided to either quit or smoke True. I smoke True” (seePollay and Dewhirst 2002 for more examples).

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit1004 Marketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS

The results of the above theorems do not depend onthe linear form of the travel costs. To see this, supposeconsumer utility were quadratic, as shown below:

Uij = V − pj − d2ij 0 (2)

If firms are located in the interior of a linear marketsuch that consumers at the edge choose not to pur-chase in equilibrium, then there are conditions whereexiting by consumers at the edge of the market leadsto increased profits. Unfortunately, the complexity ofthe expressions with quadratic travel costs makes itimpossible to derive explicit conditions that definewhen consumer exit leads to profit increases for thecompeting firms. However, a simple numerical exam-ple can be used to demonstrate the existence of suchsituations. We do this by setting V = 1, and we thencalculate the changes in profits for a range of dis-tances between firms and a range of K, as definedin Figure 1. We limit the distance between firms tobe less than 0.67, since at greater distances there aremultiple pricing equilibria after market contractionfor some levels of market shrinkage. We calculate thepercentage change in profits before and after the con-sumers exit the market, and we map the results in theform of a contour map, shown in Figure 3. There isa significant range where profits increase with con-sumer exit, and the magnitude of the increase canbe substantial: consumer exit leads to an increase inprofits of more than 15% in some cases. Furthermore,profits can increase with consumer exit even in situ-ations where a substantial fraction of consumers exit.For example, when the firms are located at a distanceof 0.67 units apart, profits can increase even if almost30% of each firm’s consumers leave the market.

Figure 3 Fractional Increase in Profits Under Symmetric Exit andQuadratic Travel Costs

0%

+5%

+5%

+10%

+15%

–20%

–40%

–60%

0%

K (

dist

ance

bet

wee

n fi

rms

and

clos

est e

xitin

g co

nsum

er)

0.20

0.35

0.40

0.45

0.50

0.55

0.60

0.65

0.70

0.75

0.80

0.25 0.30 0.35 0.40 0.45

Distance between firms

0.50 0.55 0.60 0.65 0.70

In this region, K is larger than eachfirm’s coverage area, so the change in

profits is zero

4. Exit by Consumers at theCenter of the Market

Further support for the robustness of consumer exitleading to profit growth for competing firms isobtained by considering a version of the model whereinstead of external consumers exiting the market,internal consumers (between the two firms) leave.This situation might relate to a context where die-hard consumers are strongly committed to one of thetwo competing brands (e.g., PlayStation and Xbox inthe videogame console market) and new consumersare relatively indifferent between the two brands.In many cases, this assumption seems reasonable asnovice consumers often have preferences that arepoorly defined. They may even have a poor under-standing of how the products are different.18

In this section, we consider the same model withthe same firm locations as in §3. However, insteadof considering the case where consumers exit fromthe edge of the market, we consider what happenswhen consumers exit from the center of the market.Specifically, we examine consumer exit for a fraction fof consumers in a line segment of length 2G, centeredat the midpoint between the two firms, that leave themarket (see Figure 4).

Theorem 3 (Exit from the Middle of the Mar-ket). Profits increase for both firms if a fraction f of theconsumers located in an interval of 2G centered betweenthe two firms exits the market whenever 4425

√174 −

815/114815V <D< 37V , f < 11

12 , and

4V +D56430 − 11f + 2f 25− 245 − f 5√

343 − f 57

85f − 32f 2 + 4f 3

<G<V +D

f−

45 − f 54V +D5√

3

5f√

3 − f0

Theorem 3 provides a set of sufficient conditionsfor profits to increase with such consumer exiting.We limit ourselves to sufficient conditions in order tosimplify the exposition. The upper bound on f andlower bound on G ensure the existence of a pure-strategy pricing equilibrium. The upper bound on Gis binding for profits to increase, showing that if toomany consumers exit the market, then profits willdecrease. Ultimately, we see that exiting by consumers

18 There is evidence in the behavioral literature that demonstrateshow differently novices and experts perceive and categorize choiceswithin a category (Mitchell and Dacin 1996, Cowley and Mitchell2003). Quite simply, novices are more likely to be indifferentbetween the available choices and sensitive to price. In fact, first-time buyers are known to be heaviest users of sales staff in the retailenvironment because they have so little understanding (or pref-erence) for the differences between the Xbox, PlayStation, andNintendo Wii. These consumers are thus more willing to switchbetween products than the typical consumer.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer ExitMarketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS 1005

Figure 4 Removing Some Consumers from the Middle of the Market

Firm 1 Firm 2

2G

Fraction f of these consumers exit

who are relatively indifferent between two productsin the market can lead to increasing rather thandecreasing profits.19 It seems reasonable to assumethat consumers who have a strong preference for anexisting product (i.e., that are located adjacent to oneof the products) are the least likely to leave the mar-ket, although we believe that the scenarios examinedin Theorems 1 and 2 are more common.

5. ConclusionThe models we propose provide a simple explana-tion of how firm profits can increase in shrinkingmarkets or decrease in growing markets even with-out changes in the number of competing firms or inthe products offered. Are these findings idiosyncraticbecause they rely on restrictive assumptions aboutwhich consumers exit the market? We think not. Asexplained in our discussion of the cigarette market,when a market starts to decline (and we have yet toidentify a category that does not pass through thestages of the product life cycle), the consumers whoare most likely to exit the market are those who arethe most frustrated with the current offerings (i.e., theconsumers that realize the least amount of utility fromconsumption). Our model shows how their depar-ture can help firms by reducing the competitive pres-sure between them. Of course, there is a limit to thisdynamic. Although the profits of the tobacco compa-nies held up surprisingly well through the 1980s andinto the 1990s, at some point, an industry’s declinehits a point Where the higher prices charged to theconsumers who remain active do not make up for thelost volume.20

Another aspect of our analysis relates to recentprescriptions from the CRM literature (Reinartz andKumar 2002). A constant refrain from this literatureis that some consumers are so costly to serve that afirm may be better off refusing to serve them. Thisappears to echo our findings of how departing con-sumers can lead to higher profits for incumbent firms

19 This result is qualitatively robust to other ways of modeling indif-ference between products. First, one obtains a similar result if thefirms are located at the endpoints of a Hotelling market rather thanat internal points. Second, in a separate analysis in §A.2 in theappendix, we show that in a model where consumers have hetero-geneous sensitivities to product differentiation (i.e., heterogeneoustravel costs), profits can increase if the consumers who are leastsensitive to product differentiation exit the market.

(even when the number of firms and their productattributes are kept constant). However, the findingfrom the CRM literature is based on firms carefullymeasuring the revenues and costs of serving indi-vidual customers in their CRM system and makingsure that revenues exceed the costs.21 In contrast, thefindings from our analysis emanate from the strategicinteraction of competing firms: the consumers wholeave the market in our models are worth serving.

Our analysis also raises a number of implicationsthat ought to figure in the management of decliningmarkets. First, as noted in §1, a fundamental tenet ofthe Boston Consulting Grid is that declining marketsare unattractive. Our analysis, however, shows thatwhen a market decline is driven by the departure ofconsumers who are not fully satisfied with the mar-ket’s offerings, a declining market might be every bitas attractive as a growing market. Why? Because thelikelihood of new competitors is low, and consumerswho remain in the market generally have a higherwillingness to pay. This suggests that there are oftenconditions where the conventional wisdom relatedto where firms should invest is incorrect: sometimesit pays to invest, rather than divest, in a shrinkingindustry.22

Second, the natural reaction of many managers todeclining sales is to reduce price to maintain volume.Our analysis underlines the importance of not hav-ing reflexive reactions such as this. In many cases, adecline in sales might be a signal to raise and notlower price.

Third, it is extremely important for managers tofully understand the segments of consumers who aredriving a decline when it is encountered. When thedecline is driven by consumers who appear to be coreconsumers, this is a markedly different situation thanone where the decline is driven by casual (or less com-mitted) category participants.

Finally, our results have implications for the seg-ments of consumers firms should target in decliningmarkets. At first, it might appear reasonable for afirm in a declining market to target customers who

21 In particular, the importance of accounting for indirect costs suchas advertising, service, organizational costs, and direct productcosts is emphasized in this literature (Reinartz and Kumar 2002).22 In a similar vein, if a person had invested in tobacco companiesthat did not pursue diversifications strategies in the 1982–1990 timeperiod (e.g., American Brands, Liggett & Myers), his or her returnswould have been significantly higher than average market returns.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit1006 Marketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS

have only a marginal interest in the firm’s productand are at risk to stop consuming. Our model showsthat firms may be better off to let those customersleave the market and instead focus on extracting moreprofit and sales from the customers who remain.

Appendix

A.1. Proofs

Proof of Theorem 1. For the first part of the theorem,before considering what happens when consumers exit themarket, we first note the equilibrium that occurs with noexit: p =

25 4V +D5; � =

625 4V +D52. Each firm sells to D con-

sumers in between the two outlets and to 35V − 2

5D con-sumers on the other side. Thus, if K ≥ 3

5V − 25D, then there

is no impact from consumers exiting the market. Now con-sider what happens when some consumers exit the market,such that K < 3

5V −25D. Firm i’s profits are then pi4K +D+

4p−i − pi5/25, which gives first-order conditions of pi = K +

D+pi/2. Symmetry ensures that p = 24K +D5. However, thissolution assumes that p = 24K +D5<V −K. If 24K +D5 >V −K, then firm i’s profits are pi4V − pi +D+ 4p−i − pi5/25,which are maximized at a price of p = 2

5 4V +D5. However,at this price, V − pi > K. Thus, firms price at the lower ofp = 24K +D5 or the kink point where p = V −K. This can besummarized as follows:

p =

V −K if K ≥V − 2D

31

24K +D5 if K <V − 2D

30

Note that 4V − 2D5/3 < 42V − 3D5/5 < 4V − D5/2, so theconditions where profits increase involve p = V −K. Equi-librium profits are

� = 4V −K54K +D5= VD+K4V −D5−K20 (3)

Profits will be higher after the consumer exit when VD +

K4V −D5−K2 > 625 4V +D52 →K > 42V − 3D5/5.

We must make sure that the firms do not undercut. Toundercut its rival, a firm must charge p = V −K − 2D, anddemand will be 2K+2D. One can confirm that undercuttingwill not be profitable as long as K >V − 4D.

For the second part of the theorem, taking the derivativeof (3) reveals that d�/dK = V −D−2K < 0 ⇔K > 4V −D5/2.Note that 4V −D5/2 >V − 4D when V ≤ 647 + 5

√105/37D.

Proof of Theorem 2. The calculations for the before-exitcase are presented above.

Suppose that all consumers located at a distance greaterthan K from the closest outlet toward one end of the lineexit, where K ∈ 4449V −36D5/851 43V −2D5/55. Without lossof generality, call the firm that is located near the exitingconsumers firm A, and the other firm is firm B. Then thefollowing prices form an equilibrium:

pA = V −K3 pB =V +D

3+

pA6

=V

2+

D

3−

K

60 (4)

To see this, note that if A responded to B’s price with aprice above V −K, it faces the same first-order condition itfaced before entry. Its best response would thus be to pricesuch that pDev = 4V + D5/3 + pB/6 = 45V 5/12 + 47D5/18 −

K/36. However, it is easy to check that 45V 5/12+ 47D5/18−

K/36 <V −K whenever K < 43V −2D5/5, so A would never

charge a higher price. Similarly, firm A’s first-order condi-tion associated with prices below V −K is pA = V −K+pB/2.Because pB > 0, the best response in this range is to raiseprices back up to the limit of V −K.

The remaining issue is to ensure that profits rise for thetwo firms. Profits for A are given by

4V −K5

(

K +D+V /2 +D/3 −K/6 − 4V −K5

2

)

=4V −K5414D+ 17K − 3V 5

121

whereas profits for firm B are given by 43V + 2D−K52/24.Profits for A are greater than 6

25 4V +D52 whenever K ∈

4449V − 36D5/851 43V − 2D5/55, whereas profits for B aregreater than 6

25 4V +D52 whenever K < 43V − 2D5/5.

Proof of Theorem 3. The profits before the cus-tomer exit are solved in the proof of Theorem 1 above.After the exit, the marginal consumer in equilibrium islocated within the gap (as is the case with any sym-metric equilibrium). This implies that the profits for eachfirm after exit can be represented by pj 6V − pj + D −

f · G + 41 − f 544p−j − pj5/257. Equilibrium prices and prof-its are then p1 = p2 = 24V +D− fG5/45 − f 5 and ç1 =

ç2 = 446 − 2f 54V +D− fG525/45 − f 52, respectively. Giventhe constraints on D, these profits are always higher thanthe profits with no exit (equivalently, when f = 0) wheneverG< 4V +D5/f − 445 − f 54V +D5

√35/45f

√

3 − f 5. However,there are three nonlocal deviations that must be consid-ered for this equilibrium to hold. First, one of the firmsmay deviate to a lower price such that the marginal con-sumer is located on the far side of the “exit gap” fromthe firm. In such a case, the profit of the deviating firmwould be 46D−Df + 6V − 11fG+ 2f 2G−Vf 52/4645 − f 525.The deviation profits are greater than the equilibrium prof-its whenever f < 11

12 and 4V + D56430 − 11f + 2f 25 − 245 −

f 5√

343 − f 57/485f −32f 2 +4f 35 <G. This deviation assumesthat the price is low enough that the marginal consumeris located more than a distance G from the center of theline, which occurs given the constraint on D (which keepsthe conditions simpler). Second, the firms in principle coulddeviate nonlocally by raising their prices to a level wherethe marginal consumer is located on the close side of the exitgap to them; however, such a deviation is not profitable inthe above conditions. Third and finally, we must ensure thatneither firm could profit from undercutting the other if anequilibrium price is charged. This constraint is not binding.

A.2. Example: Consumer Exit in a Market WhereConsumers Have Heterogeneous Sensitivitiesto Product DifferentiationIn this model, we obtain a similar result to the model in§4. However, in some conditions, a substantial amount ofconsumer exit is required before it leads to increased prof-its. We assume that there are two firms, Firm 1 and Firm 2,located at the opposite ends of two Hotelling markets oflength 1 (i.e., Firm 1 is located at 0, and Firm 2 is located at1). Each firm offers a single product to both markets at thesame price. Each Hotelling line represents a segment; onesegment (with mass �) has high travel costs, and the othersegment (with mass 1 −�) has low travel costs. Consumers

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer ExitMarketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS 1007

in both segments are uniformly distributed along the line,and consumer utility is given by Uij = VS −pj −�Sdij , whereS ∈ 8H1L9.23 We assume that �H > �L. Many spatial mod-els that employ this structure (e.g., Iyer 1998, Desai 2001,Ishibashi and Matsushima 2009) also assume a quality com-ponent such that consumers in the first segment are sensi-tive to both product quality and product attributes whereasconsumers in the second segment are less sensitive to both.We assume that the competing products are of equal quality.Higher sensitivity to both quality and horizontal attributescan be represented by allowing VH > VL. Such an assump-tion has no effect on the analysis as along as VH and VL arehigh enough such that no consumer considers purchasingthe outside good.

The indifferent consumer is found at the point wherethe utilities offered by the competing products are iden-tical, located at xS = 4p2 − p1 + �S5/42�S5, where xSdenotes the marginal consumer in segment S. Profits foreach firm are then ç1 = p16�xH + 41 −�5xL7 and ç2 =

p26�41 − xH 5+ 41 −�541 − xL57, respectively. Substituting themarginal consumers into the profit equation and dif-ferentiating with respect to price yields p∗

1 = p∗2 =

�H�L/441 −�5�H +��L5. Thus, the equilibrium prices are theharmonic means of the travel costs for the two segments.Because the market is covered and the equilibrium is sym-metric, the equilibrium profits are

ç∗

1 =ç∗

2 =12

�H�L

41 −�5�H +��L

0 (5)

Suppose that a fraction (1 − �) of the consumers in thelow segment exit. Analogous calculations to those abovegenerate the following the equilibrium profits:

ç∗

1 =ç∗

2 =126�+�41 −�572�H�L

�41 −�5�H +��L

0 (6)

Comparing Equation (5) with (6), it is apparent that prof-its increase with consumer exit whenever �L ≤ �H/2 andeither

• �H/424�H −�L55≤ �, or• �L/4�H − �L5 ≤ � ≤ �H/424�H −�L55 and � ≤ 4�24�H −

�L5−��L5/4�H +��L − 2��H +�24�H −�L55.Note that the finding that � must be small enough if

�L/4�H − �L5 ≤ � ≤ �H/424�H −�L55 means that profits donot increase when only a few low consumers exit the mar-ket. Rather, consumer exit is profitable only if enough cus-tomers leave the market for this range of �. This may seemcounterintuitive—after all, if too many consumers exit themarket, then profits must decrease because there are fewconsumers remaining to whom firms can sell. This intuitionis offset by the fact that the price increases from consumerexit are convex with respect to the rate of exit from themarket, and the rate at which consumers leave the mar-ket is directly proportional to the fraction of low types thatleave (i.e., 1 −�5. If only a few consumers exit, the increasein prices is negligible. However, if enough customers exit,equilibrium prices increase substantially because the firmshave less incentive to fight over the reduced mass of con-sumers in the low segment. When �= �L/4�H −�L5, profitsonly increase when all consumers in the low segment exit.

23 The results are identical if consumers have quadratic travel costs.

ReferencesBauder DC (1984) Tobacco stocks outdo industry. San Diego Union

(January 7) C-7.Coughlan AT, Soberman DA (2005) Strategic segmentation using

outlet malls. Internat. J. Res. Marketing 22(1):61–86.Cowley E, Mitchell AA (2003) The moderating effect of product

knowledge on the learning and organization of product infor-mation. J. Consumer Res. 30(3):443–454.

Desai PS (2001) Quality segmentation in spatial markets: Whendoes cannibalization affect product line design? Marketing Sci.20(3):265–283.

Gatignon H, Soberman DA (2002) Competitive response and mar-ket evolution. Weitz BA, Wensley R, Nixon R, eds. Handbook ofMarketing (Sage, London), 126–147.

Gordon M (1985) Puffing ahead: Tobacco profits buoying AmericanBrands. Barron’s 65(46):67–68.

Hague P (1985) How to survive in a declining industry. Indust. Mar-keting Digest 10(3):127–136.

Harrigan KR, Porter ME (1983) End-game strategies for decliningindustries. Harvard Bus. Rev. 61(4):111–119.

Ishibashi I, Matsushima N (2009) The existence of low-end firmsmay help high-end firms. Marketing Sci. 28(1):136–147.

Iyer GK (1998) Coordinating channels under price and non-pricecompetition. Marketing Sci. 17(4):338–355.

Keeley A (2012) Vice made nice? A high-tech alternative tocigarettes. Stanford Magazine (July/August) http://alumni.stanford.edu/get/page/magazine/article/?article_id=54751.

Kelbsch J, Meyer C, Rumpf H-J, John U, Hapke U (2005) Stages ofchange and other factors in “light” cigarette smokers. Eur. J.Public Health 15(2):146–151.

Kono E (2011) TVs selling well, but profits remain low. Daily Yomi-uri (May 28) http://www.accessmylibrary.com/article-1G1-257503973/tvs-selling-well-but.html.

Kotler P, Keller KL (2012) Marketing Management, 14th ed. (Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ), 310–314.

Kozlowski LT, Goldberg ME, Sweeney CT, Palmer RF, Pillitteri JL,Yost BA, White EL, Stine MM (1999) Smoker reactions to a“radio message” that light cigarettes are as dangerous as reg-ular cigarettes. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 1(1):67–76.

Lilien GL, Kotler P, Moorthy KS (1992) Marketing Models (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ), 551–556.

Liu H (2010) Dynamics of pricing in the video game console mar-ket: Skimming or penetration? J. Marketing Res. 47(3):428–443.

Martin A (2011) Plummeting TV prices squeeze makers and sellers.New York Times (December 27) B1.

Mitchell AA, Dacin PA (1996) The assessment of alternative mea-sures of consumer expertise. J. Consumer Res. 23(3):219–239.

NPD DisplaySearch (2010) Global LCD TV shipments reached146M in 2009, faster growth than 2008. Press release(February 22), http://www.displaysearch.com/cps/rde/xchg/displaysearch/hs.xsl/100222_gobal_lcd_tv_shipments_reached_146m_units_in_2009_faster_growth_than_2008.asp.

Pollay RW, Dewhirst T (2002) The dark side of marketing seemingly“light” cigarettes: Successful images and failed fact. TobaccoControl 11(Supplement 1):i18–i31.

Reinartz W, Kumar V (2002) The mismanagement of customer loy-alty. Harvard Bus. Rev. 80(7):4–12.

Sony (2009a) Consolidated financial results for the fiscal year endedMarch 31, 2009. Press release (May 14), Sony Corporation,Tokyo. http://www.sony.net/SonyInfo/IR/financial/fr/08q4_sony.pdf.

Sony (2009b) Supplemental information for Q1 FY2009 earnings.Press release (July 30), Sony Corporation, Tokyo. http://www.sony.net/SonyInfo/IR/financial/fr/09q1_eleki.pdf.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Pazgal, Soberman, and Thomadsen: Profit-Increasing Consumer Exit1008 Marketing Science 32(6), pp. 998–1008, © 2013 INFORMS

Strom S (2012) Soda makers scramble to fill void as sales drop.New York Times (May 15) http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/16/business/pepsi-and-competitors-scramble-as-soda-sales-drop.html.

Ticer S (1986) Tobacco company profits just won’t quit. Bus. Week22:26–27.

Wiggins PH (1985) Philip Morris, Reynolds profits rise. New YorkTimes (April 19) D.5.

Wilcox GB, Vacker B (1992) Cigarette advertising and consump-tion in the United States: 1961–1990. Internat. J. Advertising11(3):269–278.

Womach J (2003) U.S. tobacco production, consumption, andexport trends. Report, Congressional Research Service, Libraryof Congress, Washington, DC. http://new.nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL30947.pdf.

Xing W (2009) Flat-panel TV sales up, but profits not. ChinaDaily (July 13) http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2009-07/13/content_8420879.htm.

Yankeelov DM (1986) Cigarette profits up, consumption down. Bus.First 3(21):1.

Zezima K (2009) Cigarettes without smoke, or regulation.New York Times (June 1) http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/02/us/02cigarette.html.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

142.

1.14

.87]

on

20 D

ecem

ber

2013

, at 1

4:09

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.