Primary Care Provider Productivity: the Effect on...

Transcript of Primary Care Provider Productivity: the Effect on...

Running head: PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 1

Primary Care Provider Productivity: the Effect on Patient Satisfaction in the

Military Health System

MAJ Jarrod McGee, Capt. Michael McLain, MAJ Marc Skinner

Army-Baylor University Graduate Program in Health and Business Administration

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the

official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the United

States Government.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 2

Abstract

1. Purpose / Hypothesis: In May 2014, Defense Secretary, Chuck Hagel, ordered a

comprehensive review of the Military Health System, which compared it to three civilian

healthcare organizations of similar size, budget, and scope. In response to the survey, the

Army Surgeon General stated the need to improve both access and patient satisfaction. The

purpose of this study is to determine the impact of provider productivity on patient

satisfaction. After an extensive literature review, we hypothesized, as provider productivity

increased, patient satisfaction would increase as well.

2. Participants: This study uses a simple random sample of all Army health care encounters.

3. Design / Methods: This study was a quasi-experimental, one-group post-test only design,

using secondary data from the Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey tool and the Practice

Management Revenue Model. The unit of analysis was at the individual provider level. The

data was cross-sectional, and includes survey results from July 1, 2014, through December

31, 2014. We conducted an associative, multiple linear regression using SPSS v21.0.

4. Findings / Results: Provider productivity levels have no statistically significant effect on

patient satisfaction scores.

5. Conclusions: Leaders should not adjust provider productivity goals with an expectation of

affecting patient satisfaction scores.

6. Value / Relevance: Our research provides military health care leaders with the ability to

evaluate their physicians’ productivity levels and patient satisfaction scores, with confidence

that productivity levels do not affect patient satisfaction.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, productivity, military health system

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 3

Primary Care Provider Productivity: the Effect on Patient Satisfaction in the

Military Health System

In May 2014, Defense Secretary, Chuck Hagel, ordered a comprehensive review of the

Military Health System. The review compared the Military Health System to three private health

systems of similar size and scope: Kaiser Permanente; Intermountain Healthcare; and Geisinger

Health System (Kime, 2014). In October 2014, the Army Surgeon General received the results

of the Military Health System review. While the Military Health System performed on par with

the three comparable civilian institutions, there were still areas for improvement.

A few areas of particular concern to the Surgeon General are patient satisfaction and

access to care. In the Army Surgeon General’s Written Statement of Testimony to the House of

Representative’s Defense Subcommittee on Appropriations, she stated, “we will make the right

care available at the right time.” Furthermore, when discussing patient satisfaction, she stated,

“…my personal belief is that we can get better – we must be better” (Horoho, 2012, p. 6).

In his article for the Military Health System, Sauer noted the argument that increased

productivity, when measured as relative value units, comes at the expense of patient satisfaction

(2008). His study was performed at one Army Medical Treatment Facility, and he found that

lower productivity was significantly correlated with lower satisfaction (Sauer M. C., 2008). The

intended purpose of this study will examine the question of how provider productivity affects

patient satisfaction in primary care clinics in the Military Health System, with a 5% significance

level. At this stage in the research, the effects of productivity on satisfaction will be defined in

terms of monetized relative value units per full-time equivalent and patients’ overall satisfaction

with their health care providers.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 4

This study will contribute to the body of knowledge regarding the effect of productivity

on patient satisfaction, and will provide evidence to MEDCOM leadership regarding the effects

of provider productivity on patient satisfaction in a primary care setting. Furthermore, other

military health systems may be able to evaluate their respective services to determine if

increasing productivity and satisfaction, concurrently, is possible. Together, the study will allow

the service Surgeons General and other military leaders to remain competitive when compared to

their civilian counterparts, consistent with Secretary Hagel’s review of the Military Health

System.

Literature Review

This study will examine the research question of how provider productivity affects

patient satisfaction in primary care clinics in the Military Health System. Studies have reported a

positive relationship between productivity and patient satisfaction (Sauer M. C., 2008;

Glenngård, 2013). However, studies have also shown no relationship between productivity and

patient satisfaction (Mandel, et al., 2003; Wood, et al., 2009). Based on the results of the limited

studies available, we hypothesize that as provider productivity increases, so will patient

satisfaction. The remainder of this literature review will discuss the factors that affect patient

satisfaction, tied closely to the conceptual model used to frame this study, followed by the

empirical model showing how we will test the effect of provider productivity on patient

satisfaction.

Conceptual Model

In their seminal article explaining the framework for the study of access to medical care,

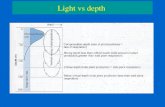

Aday and Andersen presented a conceptual model (Figure 1), which we have elected to use the

as the conceptual model for this study. According to Aday and Andersen, health policy, the

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 5

characteristics of the health delivery system, characteristics of the population at risk, and

utilization of health services all affect patient satisfaction (1974). The model includes

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the factors that affect patient satisfaction. The overall model is

adapted from Aday and Andersen (1974). *We have further modified the model to include the

construct of provider productivity, which was adapted from Bravo, Harmon, and Wood (2014).

**The characteristics of the population at risk was adapted from Andersen and Newman (1973).

***Health policy was adapted from Kim (2014).

adaptations from Kim (2014) regarding health policy. We have adapted the Aday and Andersen

conceptual model to include provider productivity. We based this decision on the unpublished

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 6

work of Bravo, Harmon, and Wood (2014, p. 8), in which they posited a conceptual model of

productivity that was driven by patient and provider demographics, pay structure, and the

environment of care.

Health policy. The construct of health policy is characterized as the starting point for

entry into the health care system, with policies and regulations all making an impact (Aday &

Andersen, 1974; Longest, 2010). For the purposes of this study, health policy is an inclusion

criterion. All patients were TRICARE beneficiaries for our dependent variable, and all providers

were Department of Defense employees (active duty military, General Schedule civilians) and

contract personnel for our primary independent variable.

Characteristics of the health delivery system. Aday and Andersen describe the

characteristics of the health delivery system as primarily organizational or structural components

of the health delivery system (1974). The unit of analysis for the characteristics of the health

delivery system is at the structural level, not the individual level (Aday & Andersen, 1974, p.

213). Tucker reported that 48.9% of the variance in patient satisfaction was explained by the

variance in the characteristics of the health delivery system (2002). The independent variables

Tucker operationalized were communication, access, and telephone access. In the only other

study we identified that investigated a characteristic of health services, Mandel and colleagues

found a significant strong and negative correlation between the number of physicians in a clinic

and patient satisfaction (2003).

Characteristics of the population at risk. The characteristics of the population at risk

is based on the work of Andersen and Newman (1973), and includes predisposing, enabling, and

illness level factors regarding an individual’s propensity to seek health care. The effect of the

characteristics of the population at risk on patient satisfaction has been well studied.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 7

Unfortunately, the majority of studies have investigated primarily predisposing variables from

the Andersen and Newman model (1973), and results are conflicting. For example, sex and age

of the patient have been reported to significantly affect patient satisfaction (Barido, Campbell-

Gauthier, Mang-Lawson, Mangelsdorff, & Finstuen, 2008; Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, &

Weinberg, 2005; Tucker, 2002; Wood, et al., 2009). Authors have also reported that sex and age

have no effect on patient satisfaction (Jackson, Chamberlin, & Kroenke, 2001; Hochman, Itzhak,

Mankuta, & Vinker, 2008). In another study investigating patient satisfaction with nurse

practitioners as the primary care provider, marital status, and education levels, both predisposing

variables, were significantly associated with patient satisfaction (Agosta, 2009). Lin and

colleagues demonstrated a statistically significant increase in patient satisfaction when the post-

visit patient-assessed length of appointment time exceeded pre-visit patient expectations (2001).

While fewer in number, studies that have investigated the illness level variables from the

Andersen and Newman model (1973) also report conflicting results. Health status has been

reported as having a significant, positive correlation with patient satisfaction (Jackson,

Chamberlin, & Kroenke, 2001; Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005; Tucker,

2002). In fact, Jackson, Chamberlin, and Kroenke reported that the variable of unmet patient

expectations was the strongest independent correlate with patient satisfaction (2001). In contrast

to these studies, Barido and colleagues reported that health status was inversely related to patient

satisfaction (2008).

Utilization of health services. The concept of utilization of health services is meant to

measure the effect of utilization of health care services (Aday & Andersen, 1974). It is where the

structural aspects of health delivery systems and the individual aspects of the patient come

together to produce utilization (Aday & Andersen, 1974). The utilization portion of the

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 8

framework consists of four variables: type, site, purpose, and time interval. Type refers to the

“kind of service received and who provided it” (Aday & Andersen, 1974, p. 214). In the

Veteran’s Administration health care system, patients assigned to a physician-led panel were

found to be 13% less satisfied with their care (Stefos, et al., 2011). Stefos and colleagues also

reported that larger panel sizes were significantly correlated to lower patient satisfaction scores

(2011). Agosta reported that nurse practitioners working in a primary care capacity have

comparable patient satisfaction outcomes to physicians (2009). Finally, Barido and colleagues

reported increased patient satisfaction when patients were seen by their primary care provider

(2008).

Site refers to the location in which care was received. Tucker reported increased patient

satisfaction among military beneficiaries abroad, as well as increased satisfaction when the

location of the health clinic was deemed convenient (2002). Mangelsdorff and colleagues

reported that in the Military Health System, facility size was not a significant predictor of patient

satisfaction (Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005). However, in a similar study

further refining a model of patient satisfaction, patient satisfaction was higher when patients

were seen in large facilities with better access to specialty care among military beneficiaries

(Barido, Campbell-Gauthier, Mang-Lawson, Mangelsdorff, & Finstuen, 2008).

Purpose refers to the reason for the visit or acuity of the condition. Patients with a self-

reported poorer health status often report increased overall patient satisfaction with the care they

receive (Mangelsdorff & Finstuen, 2003; Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005;

Barido, Campbell-Gauthier, Mang-Lawson, Mangelsdorff, & Finstuen, 2008). Hochman and

colleagues reported a significant effect between physician communication skills and patient

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 9

satisfaction, but no effect between patient satisfaction and either the purpose of the encounter or

number of prior encounters (2008).

Patient Satisfaction. Patient satisfaction is increasingly used to measure perceived

quality of health care delivery and as an outcome measure. With an ever-increasing focus on

productivity, the twin goals of productive providers and satisfied patients can seem as diametric

goals (Glenngård, 2013; Wood, et al., 2009). Patient satisfaction is defined as an attitudinal

response towards the health care system that is optimally measured shortly after a specific

episode of care (Aday & Andersen, 1974, p. 215). Mangelsdorff and Finstuen (2003) conducted

a study of patient satisfaction in the Military Health System that established who should be

surveyed, when and where the survey should be conducted, as well as survey content. Content

included data such as patient demographics, health status, satisfaction, and familiarity with

benefits (Mangelsdorff & Finstuen, 2003). This model established that the attitude of patient

satisfaction could be predicted based on three constructs: patient demographics, beliefs about the

care itself, and situational factors (Mangelsdorff & Finstuen, 2003). Demographics included age,

health status, and sex. The care itself included patient perceptions regarding the thoroughness of

treatment, how well the treatment met patient needs, overall perceived quality of care, and

explanation of procedures and tests. Situational factors included time spent waiting for the

provider and the size of the facility. This model was subsequently refined to reflect the evolution

in the field of measuring patient satisfaction, as well as changes in health policy concerns

(Mangelsdorff & Finstuen, 2003; Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005; Barido,

Campbell-Gauthier, Mang-Lawson, Mangelsdorff, & Finstuen, 2008).

The first refinement we identified (Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005)

confirmed the earlier model, with addition of several variables into each of the three constructs

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 10

of patient demographics, beliefs about the care itself, and situational factors. For patient

demographics, this refinement confirmed health status and gender, but the authors chose to

stratify age from a continuous variable into a nominal variable of age group, as predictors of

patient satisfaction. Furthermore, beneficiary category (e.g., active duty service member, active

duty family member, retiree, retiree family member) was added to the predictive model. Branch

of service was reported as a non-significant predictor variable for patient satisfaction. Among

beliefs about the care itself, four from the original model (recommend provider, thoroughness of

treatment, how well needs were met, and overall quality of care) remained significant predictors

of patient satisfaction. Two new predictors were identified: how well health care delivery met

needs and the provider’s interest in patient (Mangelsdorff, Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005).

Replication of situational variables demonstrated mixed results. The variable of time spent

waiting for a provider was divided into two variables: satisfaction with the number of minutes

spent waiting for a provider, and satisfaction with the number of days between scheduling the

appointment and the actual day of the visit. Under this refined model, only number of minutes

wait past appointment time, rate number of days between appointment and day saw provider, and

reason for visit (i.e., acuity) were significant predictors of patient satisfaction (Mangelsdorff,

Finstuen, Larsen, & Weinberg, 2005).

The last refinement we identified provided further confirmation of the empirical model of

patient satisfaction (Barido, Campbell-Gauthier, Mang-Lawson, Mangelsdorff, & Finstuen,

2008). Among the patient demographic variables, age group, health status, and gender remained

significant predictors, while beneficiary status and branch of service were not significant

predictors of patient satisfaction. Barido and colleagues confirmed satisfaction with care

received, recommend provider, thoroughness of treatment, overall quality of care, how much

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 11

helped by care, advice received, attention to what patient said, and friendliness and courtesy as

significant beliefs about the care itself variable predictors of patient satisfaction (2008). For

situational variables, the authors confirmed that waiting time, size of facility, and reason for visit

were all significant predictors of patient satisfaction.

Patient satisfaction is positively correlated with time spent with patients (Feddock, et al.,

2005; Leiba, Weiss, Carroll, Benedek, & Bar-dayan, 2002; Sauer M. C., 2008; Morrell, Evans,

Morris, & Roland, 1986). Hochman and colleagues reported a significant effect between

physician communication skills and patient satisfaction, but no effect between patient

satisfaction and either the purpose of the encounter or number of prior encounters (2008). This

represents conflicting evidence, as Mangelsdorff and colleagues found the opposite, that patient

satisfaction was significantly correlated to the purpose of the encounter (2005).

The research detailed in the previous paragraphs provided the foundation for the present

patient satisfaction survey tool in use by the U.S. Army: the Army Provider Level Satisfaction

Survey. The most recent iteration of the Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey consists of 27

questions, which collects data from the constructs of beliefs about the care itself and situational

variables. Altarum, an independent organization, maintains patient satisfaction data linked to a

specific provider by a specific appointment. Patient demographic and health care utilization data

is maintained in a separate data repository, the Military Health System Mart, and can also be

linked to a specific encounter. In spite of these rich sources of data, little is known about the

effect of provider productivity on patient satisfaction.

Provider Productivity. Productivity, as an evidence-based construct, lacks peer-

reviewed evidence regarding reliability and validity of measures used (McGlynn, 2008). There

is also a lack of consensus regarding which measure of productivity is most effective (Fetter,

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 12

Averill, Lichtenstein, & Freeman, 1984). Giuffrida and Gravelle (1999), consistent with the

McGlynn (2008) study, determined that there was no general reason to use any method versus

another when measuring productivity. Lack of uniformity in measuring productivity makes

comparison of studies of health care provider productivity challenging. One measure of

productivity in common use outside of academia is the relative value unit (Dummit, 2009).

A relative value unit is a number assigned to diagnosis and procedure codes, which ranks

the resources used to provide the service provided (Dummit, 2009). In a volume-driven health

care delivery model, the more patients a physician can evaluate, diagnose, and treat will increase

the number of relative value units, that is, increase productivity. Wood and colleagues

corroborated this effect, as they found a significant association between decreased physician time

with the patients (increased number of appointments) and increased relative value units (2009).

In a study within the Military Health System, Bravo, Harmon, and Wood posited a

conceptual model for productivity (2014). The model was tested to determine if physician pay

scale was associated with productivity and was not significant. While the Bravo, Harmon, and

Wood (2014) model has not been tested for validity, we determined it had face validity and chose

to incorporate it into the Aday and Andersen (1974) conceptual model (Figure 1). One weakness

we identified with the Bravo, Harmon, and Wood (2014) study is the model does not account for

variations in provider practice patterns. Smith and colleagues (1995) reported that physician

practice patterns (e.g., time spent with patient, and tests/radiographs in clinic) account for 84.9%

of the variance in productivity, while clinic characteristics (e.g., nurse to physician ratio, clerk to

physician ratio, and cancelled visits) explain only 8.2% of the variance in productivity (1995).

Provider Productivity and Patient Satisfaction. The majority of studies regarding the

effect of productivity on patient satisfaction have been limited in both complexity of productivity

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 13

measure and scope. Studies have reported conflicting results regarding the association between

productivity and patient satisfaction. Sauer (2008) and Glenngård (2013) reported a positive

relationship between productivity and patient satisfaction. Mandel and colleagues (2003) and

Wood and colleagues (2009) reported no relationship between productivity and patient

satisfaction. There is no clear agreement on how productivity influences patient satisfaction.

Further confounding the issue is lack of agreement on how to operationally define productivity.

Baily and Garber define productivity for health care providers as “the physical inputs

used (labor, capital, and supplies) to achieve a given level of health outcomes in treating a

specific disease” (1997, p. 146). Therefore, we chose to use a monetized relative value unit per

normalized full-time equivalent as our primary independent variable. This will directly measure

productivity while accounting for patient acuity and non-clinical provider activities.

Sauer conducted a study within the Military Health System involving a single military

treatment facility finding a statistically significant weak and direct correlation (r = 0.318, p <

0.01) between patient satisfaction and the number of encounters per provider per day (2008).

Furthermore, Sauer also reported that 16% of the variance in patient satisfaction accounts for, or

is shared with, the variance in the characteristics of health care delivery constructs of relative

value units per day and the number of provider encounters per day (2008). Glenngård (2013)

found similar results as Sauer (2008), with a direct relationship between productivity, defined as

volume of encounters, and patient satisfaction. However, there was a significant inverse

relationship between physician productivity and the enabling and illness level constructs of

social deprivation and illness, respectively (Glenngård, 2013). Finally, Wood and colleagues

concluded that there was “little or no clinically meaningful association between physician

productivity and patient satisfaction” (2009, p. 503).

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 14

Empirical Model

Our empirical model (Figure 2) shows how we are testing the effects of provider

productivity on patient satisfaction. Our dependent variable, patient satisfaction with provider, is

question four from the Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey. The raw data for satisfaction is

a five-point Likert scale ranging from completely dissatisfied to completely satisfied. The data

was delivered from the Defense Health Agency with satisfaction scores aggregated to the

provider, with patient identifying information stripped. The data was already transformed from a

five-point Likert scale into a percentage, determined by dividing the number of surveys with

question four marked as satisfied or completely satisfied by the total number of surveys returned.

Our primary independent variable is revenue per full-time equivalent. This data is readily

available from the Practice Management Revenue Model, hosted by the U.S. Army’s Command

Management System website. Our control variables are the following: provider type (by

specialty for physicians, by work site for nurse practitioners and physician assistants), region

(U.S. Army Medical Command regions), personnel category (officer, civilian, and contractor),

facility size (medical center, medical activity, and health clinic), patient-centered medical home

status, and fellowship status. Of these, patient-centered medical home status, fellowship status,

and personnel status have not been included as control variables in previous studies. We

included patient-centered medical home status because we hypothesized that care rendered in a

patient-centered medical home would be perceived as higher quality (increased patient

satisfaction). We included fellowship status as a control variable because we hypothesized that

with the increased training required to become a fellow should result in superior outcomes, and

therefore increased patient satisfaction. We included personnel category as a control variable

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 15

because we hypothesized that due to frequent reassignments for active duty providers, patient

satisfaction would be decreased for that provider type.

Figure 2. Empirical model showing the tested effect of facility type, provider type, and our

primary independent variable of revenue per full-time equivalent on patient satisfaction with

their provider, as measured by the Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey, question four.

*Dependent Variable. **Primary Independent Variable. ***Control Variables. PCMH = patient-

centered medical home, MTF = military treatment facility, FTE = full-time equivalent, APLSS =

Army provider level satisfaction survey.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 16

Methods

Our research design is a quasi-experimental, one-group post-test only, using secondary

data from the Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey tool and the Practice Management

Revenue Model. The data is cross-sectional and includes survey results from July 1, 2014,

through December 31, 2014. The patient satisfaction data is aggregated to the individual

provider; therefore, our unit of analysis is at the individual provider level.

The Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey is offered to a random sample of patients.

Military treatment facility commanders can select which providers are surveyed, but the

selection of the patients is a random process. The data for this study was a simple random

sample, including all survey results across the military health system.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are found in Figure 3. Since our research question was specific

to primary care providers, we excluded all providers not assigned to a primary care product line.

For data quality issues, we excluded all providers with fewer than ten responses (Glenngård,

2013). The U.S. military has a unique requirement to ensure all service members are medically

fit to deploy in support of a wide variety of national interests around the globe. In order to

ensure deployment needs are met, some medical providers work in a readiness or training

capacity. Those providers may be primary care providers, but they do not function primarily to

diagnose or treat. Accordingly, we excluded all providers who were not assigned to primary care

clinics. The Practice Management Revenue Model had limited missing data regarding the

facility size where 36 providers worked, and since that was a control variable, those records were

excluded. The Practice Management Revenue Model also had missing data or error terms

returned for a small number of providers’ revenue per full-time equivalent, and because that was

our primary independent variable, those records were excluded. Finally, due to the presence of

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 17

substantial outliers in our dependent variable, we elected to exclude plus and minus three

standard deviations of productivity (Field, 2009).

Figure 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 18

A list of all of our variables is shown in Table 1. We used question four from the Army

Provider Level Satisfaction Survey, satisfaction with provider, as our dependent variable. Since

our literature review identified that no measure of productivity is preferred over another

(Giuffrida & Gravelle, 1999), we elected to use revenue per full-time equivalent as our primary

independent variable. The remaining variables were used as control variables.

We analyzed the data using IBM SPSS v21.0, with an alpha significance level of .05.

Categorical control variables were dummy coded using the following variables as the base

variable: southern region for region, medical center for facility size, active duty for personnel

category, and primary care physician for provider type. We checked the data for assumptions,

and then conducted univariate and bivariate analysis. Finally, we performed a multiple linear

regression to analyze the association between our dependent and independent variables.

Running head: PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 19

Table 1

Table of Variables Included in the Empirical Model

Note. APLSS = Army Provider Level Satisfaction Survey, PMRM = Practice Management Revenue Model

Concept Measure/

Variable

Variable

Name

Use in

Analysis

Level of

Measure

Type of

Data

Measurement

Units

Data

Source Reference

Patient

Satisfaction

Satisfaction

with Provider sat DV continuous interval percent APLSS

(Barido, Campbell-

Gauthier, Mang-

Lawson,

Mangelsdorff, &

Finstuen, 2008)

Provider

Productivity

Revenue/Full-

time

Equivalent

rev IV continuous Ratio dollars

PMRM (Glenngård, 2013)

Utilization

of Health

Services

Facility Type MTF Control categorical nominal

0 = medical

center, 1 =

medical activity,

2 = Army Health

Clinic

PMRM

(Barido, Campbell-

Gauthier, Mang-

Lawson,

Mangelsdorff, &

Finstuen, 2008;

Gates, 2008)

Utilization

of Health

Services

Provider

Type doc Control categorical nominal

0 = physician, 1

= nurse

practitioner, 2 =

physician

assistant

PMRM

(Barido, Campbell-

Gauthier, Mang-

Lawson,

Mangelsdorff, &

Finstuen, 2008)

Patient

Satisfaction

# Surveys per

Provider SurvNum Control continuous Ratio number APLSS NA

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 20

Table 1, continued

Table of Variables Included in the Empirical Model

Note. PMRM = Practice Management Revenue Model, SRMC = Southern Region Medical Command, WRMC = Western Region

Medical Command, NRMC = Northern Region Medical Command, ERMC = European Region Medical Command, PRMC = Pacific

Region Medical Command, NCR = National Capital Region, PCMH = Patient-Centered Medical Home

Concept Measure/

Variable

Variable

Name

Use in

Analysis

Level of

Measure

Type of

Data

Measurement

Units

Data

Source Reference

Utilization

of Health

Services

Region reg Contol categorical Nominal

0 = SRMC, 1 =

WRMC, 2 =

NRMC, 3 =

ERMC, 4 =

PRMC, 5 = NCR

PMRM (Tucker, 2002)

Utilization

of Health

Services

Personnel

Category PersCat Control categorical Nominal

0 = AD, 1 = GS,

2 = contractor PMRM NA

Utilization

of Health

Services

Fellowship

Status fellow Control categorical Binary 0 = no, 1 = yes PMRM NA

Utilization

of Health

Services

PCMH PCMH Control categorical Binary 0 = no, 1 = yes PMRM (Lewis & Holcomb,

2012)

Running head: PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 21

Results

Descriptive statistics for our continuous variables, including the mean, median, standard

deviation, and range, are shown in Table 2. Descriptive statistics for our categorical variables,

including frequencies and percentages, are shown in Table 3. There were no missing data points

for any variable. Mean patient satisfaction is 92%, with a standard deviation of 8%. Our

primary independent variable, provider productivity, has a mean of $351,177, with a standard

deviation of $236,071.

Table 2

Table of Central Tendencies and Dispersion for Continuous Variables

Patient Satisfaction Productivity Number of Surveys

Mean .92 $351,177 55

Median .94 $318,178 48

Std. Deviation .08 $236,071 36

Range .69 $4,095,338 252

Minimum .31 $10,422 10

Maximum 1.00 $4,105,760 262

Note: Adjusted R2 = .048, F(23, 1113) = 3.516, p < .001

The frequency distribution for the dependent variable of patient satisfaction with provider

has a negative skew, which is consistent with the literature (Glenngård, 2013; Tucker, 2002).

Our overall model is significant (see note in Table 4); however, the coefficient of multiple

determination is only .048, meaning the model accounts for just 4.8% of the variance in patient

satisfaction.

Table 4 shows the multiple linear regression results with the primary independent

variable of revenue per full-time equivalent being neither significant nor meaningful. The

following control variables have a statistically significant inverse association with patient

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 22

Table 3

Table of Frequencies for Categorical Variables

Frequency Percent

Provider Type Family Physician 309 27.2

Internist 144 12.7

Field Surgeon 20 1.8

Flight Surgeon 13 1.1

Pediatrician 152 13.4

Nurse Practitioner: Primary Care 173 15.2

Nurse Practitioner: Internist 16 1.4

Nurse Practitioner: Pediatrics 10 .9

Physician Assistant: Primary Care 259 22.8

Physician Assistant: Internist 7 .6

Physician Assistant: Flight

Surgeon 34 3.0

Total 1137 100.0

Personnel

Category

Active Duty Officer 536 47.1

General Schedule Civilian 511 44.9

Contractor 90 7.9

Total 1137 100.0

PCMH No 295 25.9

Yes 842 74.1

Total 1137 100.0

Region Southern 455 40.0

Western 289 25.4

Northern 196 17.2

European 43 3.8

Pacific 76 6.7

Capital 78 6.9

Total 1137 100.0

Facility Type MEDCEN 467 41.1

MEDDAC 495 43.5

Clinic 175 15.4

Total 1137 100.0

Fellowship Status No 1135 99.8

Yes 2 .2

Total 1137 100.0

Note: Adjusted R2 = .048, F(23, 1113) = 3.516, p < .001

PCMH = Patient-Centered Medical Home, MEDCEN = Medical Center, MEDDAC = Medical

Activity

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 23

Table 4

Inferential Statistics and Regression Results

Model

Unstandardized

Coefficients

Standardized

Coefficients

b Std. Error beta

(Constant) .929 .009

Number of Surveys .000 .000 .051

Productivity 3.88 x 10-9

.000 .012

PCMH -.012 .006 -.070

Western Region -.004 .006 -.023

Northern Region .004 .007 .022

European Region .015 .013 .037

Pacific Region .011 .009 .035

Capital Region -.006 .011 -.020

MEDDAC .006 .005 .041

Clinic .014 .008 .069

Civilian -.005 .005 -.032

Contractor -.021 .009 -.077*

Internist .012 .008 .051

Field Surgeon -.041 .017 -.072*

Flight Surgeon -.035 .021 -.050

Pediatrician .000 .007 .001

Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care -.010 .007 -.049

Nurse Practitioner, Internist .027 .019 .042

Nurse Practitioner, Pediatrics .015 .024 .019

Physician Assistant, Primary Care -.034 .006 -.187**

Physician Assistant, Internist .033 .028 .034

Physician Assistant, Flight Surgeon -.032 .014 -.071*

Fellowship Trained .022 .052 .012

Note: Adjusted R2 = .048, F(23, 1113) = 3.516, p < .001

* p < .05

** p < .001

PCMH = Patient-Centered Medical Home, MEDDAC = Medical Activity

satisfaction: contractor (personnel status), field surgeon (provider type), physician assistant-

primary care (provider type), and physician assistant-field surgeon (provider type). Interestingly,

we found that the control variable patient-centered medical home approached significance at p

= .051.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 24

Discussion

The results of the study demonstrate that while the model is significant, it is not

meaningful and only accounts for 4.8% of the shared variance of patient satisfaction. Health

care leaders and administrators should not direct efforts to alter provider productivity goals and

expect an improvement in patient satisfaction. The results of this study are both consistent, and

conflicting, with the published literature. Additionally, our results provide preliminary evidence

that the number of surveys returned does not affect patient satisfaction, that fellowship status

does not affect patient satisfaction, and that personnel status does not affect patient satisfaction.

Literature

The lack of consensus among current literature made it inevitable that our results would

both support and refute the results of other studies. Perhaps the most significant result of our

study that stands in opposition to Sauer (2008) and Glenngård (2013) is the lack of significant

association between patient satisfaction and provider productivity. Although Sauer (2008)

developed a significant model dealing with health care delivery characteristics, 16% of the

variance was attributed to patient satisfaction. These results stand in contrast to the 4.8% shared

variance of our model. Additionally, counter to Tucker (2002), region of care did not have a

significant effect on the patient satisfaction with their provider.

The lack of significant effect that provider productivity has on satisfaction within our

model is concurrent with the results of Mandel et al. (2003) and Wood et al. (2009). The data for

patient satisfaction was skewed to the left, consistent with results reported by Glenngård (2013)

and Tucker (2002). Patients had a tendency to report higher scores on the satisfaction scale than

lower.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 25

Other than Glenngård’s (2013) use of 10 surveys for inclusion/exclusion criteria, we

identified no sources that discussed the correlation between patient satisfaction and the number

of surveys that a provider receives. Our research shows that there was no significant association

between patient satisfaction with the number of surveys returned. There was also a gap in the

literature regarding the effect of personnel categories, active duty, civilian, and contract

providers, on patient satisfaction. While our results demonstrate no significant association

between fellowship trained providers and patient satisfaction, these results need to be interpreted

cautiously as there were only two providers out of 1137 that were fellowship trained.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is the lack of generalizability. Our research does

permit good generalizability to primary care within the military health system. Evidence based

managers should use due diligence when attempting to apply these results to health care

providers working in specialty care clinics, and to health care facilities outside of the military

health system. The study was designed to reveal associative properties and should not be used as

a predictive model to help improve future patient satisfaction outcomes. There are other factors

which could have added to the merit of the study, including patient demographic information and

information regarding the beliefs about the care itself.

Conclusions

While our model was significant, it was not meaningful. The coefficient of multiple

determination of 4.8% shows that a substantial amount of variance is unaccounted for with our

model. Provider productivity has neither a significant, nor a meaningful impact on patient

satisfaction.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 26

Recommendations

The purpose of this study was to investigate leadership directed objectives and to

discover whether productivity has a significant impact on satisfaction. As such, the results of

this research should temper leadership expectations on adjusting productivity measures for the

purpose of improving satisfaction; the evidence is growing demonstrating no significant

association between productivity and patient satisfaction. Further research is needed on the

impact of patient demographics, provider demographics, and alternative product lines on patient

satisfaction. We recommend including command climate survey results into future studies as

provider satisfaction with their current command structure would likely have an impact on their

interaction with patients and consequently the patient’s satisfaction with the provider.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 27

References

Aday, L. A., & Andersen, R. (1974). A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health

Services Research, 208-220.

Agosta, L. J. (2009). Patient satisfaction with nurse practitioner-delivered primary healthcare

services. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21, 610-617.

doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00449.x

Andersen, R., & Newman, J. F. (1973). Societal and individual determinants of medical care

utilization in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and

Society, 51(1), 95-124. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00428.x

Baily, M. N., & Garber, A. M. (1997). Health care productivity. Brookings Papers on Economic

Activity, 143-201.

Barido, G. T., Campbell-Gauthier, G. D., Mang-Lawson, A. M., Mangelsdorff, A. D., &

Finstuen, K. (2008). Patient Satisfaction in military medicine: model refinement and

assessment of continuity of care effects. Military Medicine, 173(7), 641-646.

Bravo, Harmon, & Wood. (2014). The effect of general schedule pay structure on physician

productivity. San Antonio: Army-Baylor University Graduate Program in Health and

Business Administration.

Dummit, L. A. (2009). The basics: relative value units. Washington, D.C.: The George

Washington University.

Feddock, C. A., Hoellein, A. R., Griffith, C. H., Wilson, J. F., Bowerman, J. L., Becker, N. S., &

Caudill, T. S. (2005). Can physicians improve patient satisfaction with long waiting

times? Evaluation & The Health Professions, 28(1), 40-52.

doi:10.1177/0163278704273084

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 28

Fetter, R. B., Averill, R. F., Lichtenstein, J. L., & Freeman, J. L. (1984). Ambulatory visit groups:

a framework for measuring productivity in ambulatory care. Health Services Research,

19(4), 415-437.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd. ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications Inc.

Gates, T. M. (2008). Quantitative analysis of contributing factors affecting patient satisfaction in

family medicine service clinics at Brooke Army Medical Center. San Antonio: Army-

Baylor University Graduate Program in Health and Business Administration.

Giuffrida, A., & Gravelle, H. (1999). Measuring performance in primary care: econometric

analysis and DEA. Heslington: The University of York.

Glenngård, A. H. (2013). Productivity and patient satisfaction in primary care - conflicting or

compatible goals? Health Policy, 111, 157-165.

Hochman, O., Itzhak, B., Mankuta, D., & Vinker, S. (2008). The relation between good

communication skills on the part of the physician and patient satisfaction in a military

setting. Military Medicine, 173(9), 879-881.

Horoho, P. (2012). Written Statement of Lieutenant General Patricia D. Horoho, Testimony for

Committee on Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense. Washington, D.C. : United

States House of Representatives, Second Session, 112th Congress.

Jackson, J. L., Chamberlin, J., & Kroenke, K. (2001). Predictors of patient satisfaction. Social

Science and Medicine, 52, 609-620.

Kim, F. S. (2014, December). 201440 HCA 5411 01. Retrieved from Baylor University Canvas

data: https://baylor.instructure.com/courses/11098/files

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 29

Kime, P. (2014, Oct 23). 'We cannot accept average,' surgeons general say. Retrieved Jan 10,

2015, from The Military Times:

http://archive.militarytimes.com/article/20141023/BENEFITS06/310230040/-We-cannot-

accept-average-surgeons-general-say

Leiba, A., Weiss, Y., Carroll, J. S., Benedek, P., & Bar-dayan, Y. (2002). Waiting time is a major

predictor of patient satisfaction in a primary military clinic. Military Medicine, 167(10),

842-845.

Lewis, P. C., & Holcomb, B. (2012). A model for patient-centered army primary care. Military

Medicine, 177-183.

Lin, C.-T., Albertson, G. A., Schilling, L. M., Cyran, E. M., Anderson, S. N., Ware, L., &

Anderson, R. J. (2001). Is patients' perception of time spent with the physician a

determinant of ambulatory patient satisfaction? Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 1437-

1442.

Longest, B. B. (2010). Health policymaking in the United States (Fifth ed.). Chicago: Health

Administration Press.

Mandel, D., Zimlichman, E., Wartenfeld, R., Vinker, S., Mimouni, F. B., & Kreiss, Y. (2003).

Primary care clinic size and patient satisfaction in a military setting. American Journal of

Medical Quality, 18(6), 251-255.

Mangelsdorff, A. D., & Finstuen, K. (2003). Patient satisfaction in military medicine: status and

an empirical test of a model. Military Medicine, 168, 744-749.

Mangelsdorff, A. D., Finstuen, K., Larsen, S. D., & Weinberg, E. J. (2005). Patient satisfaction in

military medicine: model refinement and assessment of department of defense effects.

Military Medicine, 170(4), 309-314.

PROVIDER PRODUCTIVITY AND PATIENT SATISFACTION 30

McGlynn, E. A. (2008). Identifying, categorizing, and evaluating health care efficiency

measures. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Morrell, D. C., Evans, M. E., Morris, R. W., & Roland, M. O. (1986). The "five minute"

consultation: effect of time constraint on clinical content and patient satisfaction. British

Medical Journal, 292, 870-873.

Sauer, M. (2008). Patient Satisfaction and Productivity. Fort Jackson: Unites States Army.

Sauer, M. C. (2008). Patient satisfaction and productivity. San Antonio: Army-Baylor University

Graduate Program in Health and Business Administration.

Smith, D. M., Martin, D. K., Langefeld, C. D., Miller, M. E., & Freedman, J. A. (1995). Primary

care physician productivity: the physician factor. Journal of General Internal Medicine,

10, 495-503.

Stefos, T., Burgess, J. F., Mayo-Smith, M. F., Frisbee, K. L., Harvey, H. B., Lehner, L., . . .

Moran, E. (2011). The effect of physician panel size on health care outcomes. Health

Services Management Research, 24, 96-105. doi:10.1258/hsmr.2011.011001

Tucker, J. L. (2002). The moderators of patient satisfaction. Journal of Management in Medicine,

16(1), 48-66.

Wood, G. C., Spahr, R., Gerdes, J., Daar, Z. S., Hutchinson, R., & Stewart, W. F. (2009). Patient

satisfaction and physician productivity: complementary or mutually exclusive? American

Journal of Medical Quality, 24(6), 498-504.