BLM Lower Sonoran Field Office Arizona. BLM Lower Sonoran Field Office Arizona.

Post-Trial Filing by BLM

-

Upload

rushdiesrocket -

Category

Documents

-

view

60 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Post-Trial Filing by BLM

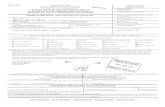

COMMONWEALTH OF MAS SACHUSETTSTRIAL DEPARTMENT

LAND COURT

BRISTOL, ss

LANDING AT SOUTH PARKCONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION.

Plaintiff

vs.

BORDEN LIGHT MARINA. INC..Defendant/PlaintiffIn Counterclaim

vs.

LANDING AT SOUTH PARKCONDOMINIUM AS SOCIATION,

Defendant inCounterclaim

DOCKET NO. 99 Misc 254067(JCC)

POST-TRIAL BRIEF OFDEFENDANT/PLAINTIFF INCOI'NTERCLAIM, BORDENLIGHT MARINA" INC.

)))))I

)I

))l

I

)I

)

The Defendant/Plaintiff in Counterclaim, Borden Light Marina, Inc. ("BLM"), submits

this Post-Trial Brief for consideration by the Court.

I. INTRODUCTION'

This action was first filed by the Plaintiff, Landing at South Park Condominium

Association ("LSP"), in February of 1999. The Complaint claimed jurisdiction under G.L. c.

185, $1(k) and G.L. c. 2314, $1. The Complaint alleged trespass and nuisance and sought a

declaration of the rights of the parties to use and occupy a 20-foot wide strip of BLM property

' All parenthetical references Tr. Vol. _ and Ex._ are to the trial transcript volumes and pages, and theexhibits admitted at trial, respectively.

adjacent to the LSP property. Specifically, the original Complaint alleged Trespass in Violation

of Visual Easement (Count I); Trespass in Violation of an Erosion Control Easement (Count II);

Private Nuisance (Count III); Negligence (Count IV); Declaratory Judgment (Count V); and a

Request for Injunctive Relief (Count VI).

The Defendant answered the Plaintiff s Complaint and included a Counterclaim alleging

trespass by LSP onto BLM's property as the result of encroachments by LSP's building

improvements and as the result of LSP's managers, agents, seryants, employees and members

wrongfully entering upon BLM's property to mow grass and cut down and remove BLM's trees

and protective plants. The Plaintiff answered Defendant's Counterclaims.

On May 23, 2A00, the Court entered a Preliminary Injunction (Kilborn, J.) enjoining

BLM until further order of the Court from undertaking certain actions, including "Engaging in

construction within the Erosion Control Easement recorded at Fall River District Registry of

Deeds at Book 1724,Page327." (Ex.15).

On or about June 3, 2010, LSP filed a Complaint for Contempt against BLM alleging a

violation of the Preliminary Injunction entered by the Court ten years earlier on May 23,200A.

BLM answered the Complaint for Contempt, raising various defenses, including laches and

waiver. A hearing on LSP's application for a Preliminary Injunction was held on October 12,

2010, and after hearing, the Court took the matter under advisement pending completion of ttre

trial of the underlying case.2

'At the conclusion of the trial, the court entered a Preliminary Injunction pending final disposition of the case.The Preliminary Injunction enjoined the Defendant from using the 20 ft. easement area adjacent to the 630+l- ft.long retaining wall constructed between 2008 and 2009 for storage purposes of any kind pending fur*rer Order ofthe Court. The Defendant complied with the Orderby removing all boats and equipment from the areawithin thetime frame set forth by the Court.

On or about October 1, 2010, the Plainti amended its Complaint wherein it abandoned

original Count Ill-Private Nuisance and original Count IV-Negligence, and added for the first

time allegations that the construction of a retaining wall within the 20 foot non-exclusive

easement violated the terms of the easement and that boats are structures for purposes of the

visual easement. At the time of the filing of the original complaint in 1999, a substantial portion

of the retaining wall had been constructed and boats were being stored above elevation 19 feet

above mean sea level and within the 20 foot non-exclusive easement area.

On November 15, 201,0, the Defendant filed an Amended Answer to the Amended

Complaint, once again including its Counterclaims.

The case was heard on November 8, 9 and 10, 201A, and concluded on January 19,

2011.

II. F'ACTUAL BACKGROT]ND

The Plaintiff is the Board of Managers of The Landing at South Park Condominium

Association, the governing body of the owners of the condominium units at LSP. (Tr. Vol. II

98). The LSP property consists of 140 condominium units built on Lots 1 and2 as shown on a

plan entitled "Division of Land in Fall River, Massachusetts, Belonging to Green River Realty

Trust dated July 14, 1986-, with a combined area of 7.73 acres. (Tr. Vol. I3) (Ex. 16). The

BLM property is shown as l,ot 3 on Exhibit 16 and consists of 3.5 acres. Subsequently, Lot 3

was divided into Lots A and B. Lot A was conveyed to "The Admiralty, Inc." and Lot B was

retained by BLM. (Tr. Vol. lV 74-75) (Ex.l9). The Admiralty, Inc. is not a party to this action,

and Lot A as shown on the referenced plan is not at issue.

BLM is a fulI service marina consisting of 27A sHps, fuel services, boat maintenance and

repalr, clubhouse and pool areas, docking facilities, boat storage and food services. (Ex. 34,

Photographs 25,26,27,28,29). The marina is licensed for up to 310 slips. (Tr. Vol. III 139).

ln addition to the docking facilities and food services, the usual operation of the marina consists

of hauling boats out of the water in the fall, power washing and winterizing them, servicing the

boats and then preparing them for launching and launching them in the spring. BLM then

conducts activities throughout the summer, which include fishing tournaments, swimming

lessons and organizing cruises. (Tr. Vol. III 135-137).

The development of the condominiums and the marina is the product of a vision by Mr.

John C. Lund, who took his first steps to develop the property in 1985 when he and his business

parbrer, Brian R. Corey, obtained an Option to Purchase the entire parcel. (Tr. Vol. IV 67). :_

Historically the property, which is zoned Industrial, was owned by Penn Central

Railroad and had been improved by railroad tracks and a turntable. (Tr. Vol. IV 66). In 1985,

when Mr. John C. Lund secured the Option to Purchase, tlre railroad tracks and turntable had

been removed, and there were twenty-six shacks situated along the shoreline. (Tr. Vol. IV 66).

One of the terms of the Option to Purchase was that Mr. Lund and his partner were required to

remove the twenty-six shacks, which they did. Some of the shacks and the existing conditions

in 1985 of what would become the LSP and BLM properties are shown as Exhibit 34,

Photographs 1,9, 34,37,38,40, 4I and47.

The original development concept in 1985-1986 was to build a full service marina on

the waterfront with 140 condominium units overlooking the marina, together with a 16-story

1 tl| Ftrt*high-tit"_b94fu_ut th" tgutherly end of lhe property. (Tr. Vol. IV 63-69). The southerly end

of the property is adjacent to the King Philip Boat Club. (Tr. Vol. IV 69). The original concept

4

also included some buildings between the condominiums and the shoreline. (Tr. Vol. IV 69).

The use of those buildings was undetermined at that time, but storage and marina related

activities were contemplated. Lund and Corey never intended to be the developer of thg

condominium portion of the development. (Tr. Vol. IV 70). They sought, through the services

of a broker, third parties to do so. (Tr. Vol. IV 70). Keith Development Corp. of Stoughton,I

Massachusetts, subsequently purchased an option from Lund and Corey to buy Lots 1 andZ and

to develop the condominiums. (Tr. Vol. W 70 and72).

Thereafter, plans to develop the property progressed. In particular, the high-rise

component of the marina project moved from the southerly to the tj1ther'ly end of the property

and some contemplated buildings on the marina property were eliminated. (Tr. Vol. IV 7t-72).

The parcel shown as Lot A on Exhibit 19, now owned by The Admiralty, Inc., and became the

site of the proposed high-rise. (Tr. Vol. fV 75) @x.19). Ultimately, in September of 1986, Keith

Development Corp., exercised its option and purchased Lots I and 2, and Lund and Corey

purchased Lot 3. (Tr. Vol. lY 7l-73). Keilh Development Corp. took title to Lots 1 and 2 as

The Landing at South Park, Inc., and John C. Lund and Brian R. Corey took title to Lot 3 as

individuals. (Exs. 1 & 2). The closings on both properties took place simultaneously. (Tr. Vol.

IV 73). The deed from Leo M. Kelly, Trustee of Green River Realty Trust, to Lund and Corey

for Lot 3 conveyed that property subject to various easements, and made reference to a visual

easement and a 2Q-foot easement for the benefit of Lots I and 2. (Ex.l). The deed to The

Landing at South Park, Inc., also made reference to the visual easement and 2O-foot easement

as appurtenant to the premises conveyed. (Exs.l and2). There were other easements referred to

in the deeds, including an access easement, which are not at issue in the case at bar.

BLM contends that the easements at issue in this case were created not by grant or

reservation in the deeds, but rather by express grant set forth in separate documents executed at

the closing and recorded with the Bristol County Fall River District Registry of Deeds. (Exs. 4

and 5). The language in the deeds @xs. 1 and2) contemplates the execution of specific grants

of easement subsequent to the deeds. Unlike the specificity used for the access easement, these

deeds merely referenced general termq for the contemplated visual easement and 20-foot

easement, with the particulars subsequently to be set forth by specific grants. (Exs. 4 and 5).

This interpretation is bolstered by the fact that when LSP granted a partial release of certain

rights under the non-exclusive easement, it referred not to the deed (Ex. 2), but, rather, to the

grant of easement captioned "Non-Exclusive Easement". (Exs. 5 and 7).

Although, the language in the deed relating to the visual easement differs in minor

respects from the terms of the easement itself, BLM maintains that such differences are of no

consequence to the rights of the dominant and servient estates; that is, the rights granted and

limitations imposed are the same regardless of whether the Court interprets the easements under

the references in the deeds or the specific grants. In its Amended Complaint, the Plaintiff

pleads the benefit of easements under Exhibits 1,2, 4 and 5 without distinguishing the rights

granted or reserved in each. BLM maintains that the operative documents for determining the

rights of the parties to the visual easement and the 20-foot non-exclusive easement are Exhibits

4 and 5 respectively.

Lund and Corey transferred title to the marina property (Lot 3 on Ex. 16) to Borden

Light Marina, Inc. on July 25, 1989. As noted above, a portion of Lot 3 was cut out, labeled

Lot A, and transferred to The Admiralty, Inc., and again, is not part of this case.

After acquiring title to the property, BLM commenced the permitting process to build

the marina. It filed an application under M.G.L.A. c. 91 with the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts, Department of Environmental Quality Engineering "for a license to construct

and maintain floats, finger floats, mooring piles, gangways, fixed piers, fixed and floating wave

attenuators, boat ramp, riprap, roadway, walkway, parking spaces, public overlooks and other

marina related facilities." (Ex. 7). The license applied for is known as a Chapter 9lWaterways

License. The details of the proposed marina were set forth on DEQE License Plan No. 1848,

Sheets 1-15, titled: "Plans Accompanying Petition of Borden Light Marina, Inc., License No.

1848." (Ex.7).

On December 19, 1988, the license was approved to allow a colnmercial and

recreational boating facility. Id. The License was recorded at the Bristol County Fall River

District Registry of Deeds on December 21, 1988. Id. The recording took place prior to the

construction of the condominiums. The License, as approved, provided for 410 slips, 253

parking spaces, an l8-foot asphalt roadway beginning at Club Street at the southerly end of

BLM and running northerly to Ferry Street, and among other things, a retaining wall with

portions of the wall within 10 feet of the common property line as shown on Sheets 9-12 and I5

of license plans. Id.

After the issuance of Waterways License No. 1848, the Fall River Conservation

Commission issued an Order of Conditions dated February 8, 1991, based in part upon the same

plans that accompanied the Waterways License application. (Ex. 9). Waterways License No.

1848 was amended at various times over the subsequent years. See Waterways License No.

8001 (Ex. l1), Waterways License No. 9876 (Ex. l4), and a Draft License issued in 2010. (Tr.

Vol. III 143-144). Corresponding Orders of Conditions issued from the Fall River

Conservation Commission and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

@xs. 9, 10, 12, 13, 25 and 26). The Orders of Conditions that issued carried forward the

retaining wall as shown on the original Waterways License No. 1848 and on the subsequent

Waterways Licenses that issued. (Exs.7, l l and 14).

The significance of the various Waterways Licenses and Orders of Conditions rests with

the public hearing process and public notice requirements for each. Furthermore, each

Waterways License and Order of Conditions was required to be recorded at the Bristol County

Fall River District Registry of Deeds providing notice to the world. In addition, notice of the

first Waterways License application was sent to Mr. John Keith, Principal of Keith

Development Corp,, the developer of the condominium project. (Tr. Vol. tV 70, 71,79,82 and,

89). The license application was filed before 1988, establishing notice to the developer of the

condominium project that the BLM property would be developed as a marina and that a

retaining wall would be constructed in the vicinity of the common property line and located, at

some points, as close as l0 feet from the property line. (Ex. 7, Sheets 9-13 & 15) (Tr. Vol. III

I42-I44). Once recorded, all subsequent owners took title to their respective units with notice

of all recorded documents.

Subsequent to receiving the Waterways License and Orders of Conditions, Mr. John

Lund, President of BLM, started construction of the marina. When construction commenced in

1989, BLM excavated into the embankment adjacent to the common property line between

BLM and LSP and constructed a retaining wall in phases beginning in 1989 and continuing

through 2009. (Tr. Vol. IV 85-86). Mr. John C. Lund testified that the first part of the retaining

wall constructed was in front of Buildings l1- 12, where BLM constructed a 4-foot retaining

wall (Tr. Vol. IV 83), which was subsequently modified by Keith Development Corp. (Tr. Vol.

IV 84). Note that Michael Lund indentified the addition of the wall by Keith development as in

front of buildings 10 and 11. (Tr. Vol. III 106). Building l0 is actually the one fronting on the

wall that was added onto by Keith development. See also Exhibit 2l for building identification

numbers. The wall in front of Buildings 11 and 12 as built by BLM was 4 feet high on each end

and 10 feet high in the middle. (Tr. Vol. IV 83). The modifications by Keith Development

Corp. increased the height of the wall to 10 feet in that area. (Ex. 34, Photographs 7,35,49 and,

51). Keith Development was building the condominiums for the Landing at South Park, Inc.,

LSP's predecessor in title.

Throughout the 20 years during which the retaining wall was being constructed, the

construction materials for the wall varied. The first section of wall was poured concrete, and

then a portion was steel sheet piling, with the remainder being a segmented concrete block wall.

(Ex. 3a). The steel sheet piling was used at the point where the condominium foundations were

in close proximity to the property line. (Tr. Vol. IV 87).

As previously stated, this Court entered a Preliminary Injunction in May of 2000 that

prohibited construction activity within the 2O-foot easement area. (Ex. 15). Nevertheless, the

parties had discussions about the retaining wall subsequent to the date of entry of the

Injunction, and, in fact, the parties came to an agreement that allowed filther construction of

the retaining wall. (Tr. Vol. M2-94) (Ex. 28 & 29). Mr. John C. Lund testified that from

October 8,2002,1o 2010, no one from LSP objected to the retaining wall construction and ttiat

the retaining wall had been completed before he received the first objection in 2010. (Tr. Vol.

IV 94). Mr. John C. Lund further te'stified that he personally observed the retaining wall being

built and that he observed members of the LSP Board of Managers watching the construction of

the retaining wall. (Tr. Vol. IV 95). He testified that during the construction work on the

retaining wall in 2008-2009, he observed and spoke with members of the Board of Managers qf

LSP, including Marcel Daquay, Bert Bouffard, Paul Beatti and Charles Schnitzlein. (Tr. Vol. IV

153-156). Mr. John C. Lund fuither testified that the individuals identified above never asked

him to stop construction of the retaining wall. (Tr. Vol. IV 156).

Mr. John C. Lund testified as to the scope of the marina's operations and specifically

noted that the storage of boats is a usual part of its business. (Tr. Vol. IV 96-101). He testified

that it took him almost 22 yearsto develop the marina to the point where it exists today. (Tr.

Vol' IV 101). The facts as established by Mr. John C. Lund's testimony are consistent with

those set forth in Michael Lund's testimony. Michael Lund testified in detail about the areas

depicted in Exhibit 34, Photographs 1 through 51" (Tr. Vol. III 94-145). Of parricular

importance is the photographic evidence set forth in these exhibits depicting the state of the

LSP and BLM properties in 1986 and the following years as development of both parcels

progressed through 2009.(Ex. 34, Photographs I through 5l).

Michael Lund detailed in his direct testimony the excavation of the embankment,

starting in 1986 and ending in 2009. (Tr. Vol. III 94-145) (Ex. 34, Photographs I through 5t).

These exhibits clearly establish pre-existing conditions, the time it took to build the marina, the

extent of the construction work undertaken in plain view of LSP, and LSP's failure to take any

reasonable steps to curtail the work about which it now complains. (Tr. Vol. III 117).

Mr. Michael Lund confirmed the receipt of a "thank you" letter from the LSP Board of

Managers dated October 2,20A8. (Tr. Vol. III 119) (Ex. 38). He testified that the manner ini

which BLM created storage space for vessels has been consistently the same since 1988-that

is, excavate the embankment, add revetment and construct retaining walls. (Tr. Vol. III 139-

140). The marina evolved over two decades. BLM's efforts were constant, and LSP had every

10

opporhmity to protect the interests it now claims have been violated. LSP took no meaningful

steps to do so.

Through the testimony of Michael Lund, Exhibit 34, Photographs 1-51 were

admitted into evidence. Photographs 4,5j7,8,1 4,21,22,39,42,49, and 51 of Exhibit 3,4 aIl depict

construction activity or retaining walls built prior to filing of the original complaint wherein

LSP did not challenge the excavation of the embankment or the construction of the walls. This

is compelling evidence of the state of mind of the parties to the easement at the time the

easement was drafted in 1986 until the complaint was amended in October of 2010, a period of

24yearc.

The Plaintiff failed to offer any evidence to dispute most of the facts established by the

testimony of Mr. John C. Lund and Mr. Michael Lund.

IMr. Bertrand Bouffard testified for LSP. He testified that he moved into LSP, Building

3, Unit 304, in 2001. (Tr. Vol. I 49). It is significant to note that by that time, Waterways

Licenses Nos. 1848 and 8001, togethel with four Orders of Conditions from the Fall River

Conservation Commission and/or Massachusetts DEP, and the deed to Borden Light Marina,

Inc., had all been recorded at the Bristol County Fall River District Registry of Deeds,

providing notice to the world that a marina was to be built on the BLM property. (Exs. 7, 8, 9,

10, 1l ari- tZ). These documents establish the scope of the marina, which clearly includes the

work at the south end of the marina properfy, which was the focus of LSP's evidence at trial.

To the extent Mr. Bouffard testified as an individual, and to the extent such testimony is

relevant, he took title to his unit with actual knowledge of the fuIl build-out of the marina by

virtue of the recorded documents; and to the extent he testified as a member of LSP Board of

Managers, the Board was a party to the original development plan. (Exs. 1, 2,3,4 and 5).

ll

Mr. Bouffard, who resides in Building 3, the southernmost building, became a member

of the Board of Managers in 2004. (Tr. Vol. I61). He served as chairman in 2010. (Tr. Vol. I

62). ln 2007, Mr. Bouffard was asked by his fellow Board of Managers of LSP if he would

approach Mr. John C. Lund and ask him to add an additional row of blocks to the block wall

BLM was then constructing. (Tr. Vol. I 65). The Lunds complied with the request. (Tr. Vol. I

65). lvk. Bouffard acknowledged this aclpommodation on behalf of the LSP Board by thanking

the Lunds for their efforts. (Tr. Vol. I 66) (Ex. 38). Mr. Bouffard testified that at the time

Exhibit 38 was signed, he and the Board of Managers did not know of the Preliminary

Injunction that issued in 2000. (Tr. Vol. I 71). His testimony strains credibility. He

acknowledged the 2006 Settlement Agreement, which he signed, and which makes reference to

the Land Court action. (Ex. 39). In fact, all three of the individuals who testified on behalf of

LSP-- Mr. Daquay, Mr. Bouffard and Mr. Schnitzlein--all signed the 2006 Settlement

Agreement as Managers of LSP. (Ex. 38). At all times relevant to the Settlement Agreement,

LSP was represented by legal counsel. (Tr. Vol. I 118). Mr. Bouffard testified that when he

observed the retaining wall construction in 2009, he, acting on behalf of the Board of Managers,

went to Fall River City Hall to inquire about permits for the work. (Tr. Vol. I 104-107).

Curiously, this was when construction of the retaining wall approached his unit in Building 3.

Mr. Bouffard testified that he was a businessman and had developed land. (Tr. Vol. I

116). He testified that he had retained the services of professionals such as land surveyors and

attomeys. (Tr. Vol. I 116). Mr. Bouffard testified as to his knowledge of hauling a boat out of

the water and the steps necessary to winterize a vessel. (Tr. Vol. I 138-140). He was an assistant

harhormaster in Portsmouth, Rhode Island for ten years. (Tr. Vol. I 135). He also testified that

when a boat is stored for the winter, it is not affixed to the ground. (Tr. Vol. I 140-142). He

12

also testified repeatedly about the effect the marina had upon "his" building and his unit. (Tr.

Vol. I 145-148). Mr. Bouffard testified that the residents of LSP can no longer walk around the

perimeter of the property. (Tr. Vol. I 155). To the extent that he was referring to the area within

the 20-foot easement that was excavated by BLM, his testimony is irrelevant because the terms

of the 20-foot easement do not give LSP residents any right to walk within the easement area,

and they are committing a trespass when they do so. (Tr. Vol. I 154,161-162). I

Mr. Marcel R. Daquay also testified for the Plaintiff. He testified that he has resided in

Building 4, Unit 401, since 2002, and he has been a member of the Board of Managers since

2005. (Tr. Vol. II 65-66). Like Mr. Bouffard, Mr. Daquay purchased his unit after the recording

of the two Massachusetts G.L. c. 9l Waterways Licenses and the series of Orders of Conditions

from the Fall River Conservation Commission and Massachusetts DEP, which, again,

constitutes actual notice to the world. (Exs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12). Any testimony that he was

not aware of the extent of the BLM build-out, as a unit owner, or as a member of the Board of

Managers, contradicts the public notice he had in the form of the recorded documents at the

Bristol County Fall River District Registry of Deeds. His testimony as to the changes in the

marina from the time he moved into LSP in 2001 up through the dates of various photographs

he referred to during his testimony is irrelevant because the issues at trial relate solelv to the 20-

foot non-exclusive easement and to the visual easement.

Mr. Daquay, like Mr. Bouffard, also testified that he was a member of the Board of

Managers of LSP in 2006 when a Settlement Agreement was signed and that he in fact signed

the Agreement. (Tr. Vol. II 7l-72). Although he testified that the Board of Managers was

represented by the Law Firrn of Marcus Erico during negotiations leading up to the signing of

the Settlement Agreement, he disclaimed any knowledge of the pending Land Court litigation

l3

and of the Preliminary Injunction. (Tr. Vol. II 72-73). That testimony as to lack of knowledge

is incredible because the Land Court litigation was referenced in the Settlement Agreement that

he and the other members of the Board of Managers signed. (Ex. 39).

Apparently, LSP would like the Court to conclude that it was being advised as to the

status of the pending litigation by the Lunds, despite the fact that it was represented by counsel

at all times relevant hereto. (Tr. Vol. lI 74-77). Mr. Daquay admitted that the Board of

Managers was aware of the construction and excavation work that commenced in 2008. (Tr.

Vol. II 76'77). In fact, Mr. Daquay testified that he watched the construction every day (Tr.

Vol. II 83) and that the work done in 2009 was completed with full knowledge of the Board of

Managers. (Tr. Vol.II 103-104).

Mr. Charles E. Schnitzlein, Jr., testified on behalf of LSP. He testified that he has been

a resident of LSP since 1998, a member of the Board of Managers since 20A5, and he was

chairman of said Board in 2010. (Tr. Vol. 1I176-178). Like the other unit owners rvho testified,

Mr. Schnitzlein took title to his unit subject to, and with notice of, all of the recorded

documents depicting the build-out of the marin4 and his personal objection to the expansion of

the marina is irrelevant. Mr. Schnitzlein testified that the Board of Managers was aware that

the Settlement Agreement (Ex. 39) provided for retaining walls being constructed after atrigger

event occurred, and not before. (Tr. Vol: II 191). He testified that the Board of Managers was

aware that the retaining wall was constructed, albeit prematurely, under the terms of the

Settlement Agreement, but the Board assumed that the Settlement Agreement would "take

place". (Tr. Vol. 1I197). LSP did not submit a plan showing the 20-foot easement area and the

location of the retaining wall within that area. Mr. Schnitzlein testified that he was aware of the

pending litigation referenced in the Settlement Agreement (Ex. 39) when he signed it, but that

l4

he didn't inquire as to the terms of the litigation or of its nature or subject matter. (Tr. Vol. III

15-17). Mr. Schnitzlein also testified consistently with the other LSP Managers that the Board

of Managers requested BLM to add to the height of the block wall BLM was constructing by

adding an additional row of blocks. (Tr. Vol. lII22-23). Mr. Schnitzlein also acknowledged the

"thank you" letter from LSP to BLM referencing that raising of the height of a portion of the

wall. (Tr. Vol. III 21) (Ex. 38). The *Thank you" letter issued during the one year that LSP was

"investigating" BLM's construction activities. (Tr. Vol. III 20-22). Mr. Schnitzlein testified

that the Board of Managers of LSP did not realize that BLM would expand its operation. (Tr.

Vol. III 35). That testimony is incredible based upon the records at the Bristol County Fdil

River registry of Deeds. Mr. Schnitzlein resides in building 2, Unit 202, in close proximity to

buildings 3 and 4, nearthe south entrancb to the marina. (Tr. Vol. lI 177)(Ex. 21). He testified

that BLM stored boats within the 20-fooi easement area in 2005 when he became a member of

the Board of Managers and that the Board did not object. It would appear that, like other

members of the Board of managers, he did not object to the marina activities until he perceived

that they had a direct impact upon his unit at LSP.

III. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTS

(r) Visual Easement

i

LSP has the benefit of a visual easement due west over a portion of BLM's property.

@x.a). The limits of the visual easement are set forth in the grant. (Ex. a).

l

LSP has the burden of proving that BLM is in violation of the visual easement by (1)

storing boats within the visual easement area 19 feet above mean sea level (MSL), and/or (2)

constructing and maintaining two building roofs within the visual easement area 19 feet above

15

i

MSL. LSP has not met its burden on either count. LSP frst raised the issue of a boat beinsia

"structure" when it amended its 1999 colnplaint in 2010.

The benefit of the easement to LSP is for a o'view unobstructed bv anv structure in the

area 19 feet above Mean Sea Level...." LSP offered no evidence at trial that a boat is a

"structure" as that term is used in the grant of easement. To the contrary, BLM offered

evidence that it is a licensed marina under M.G.L.A. c.91, and that its operations as such are

governed by 310 CMR 9.00, et seq. (Ex. 23). BLM's operations fall under both the definition

of a boatyard and a marina as set forth in the regulations. The regulations also define a

structwe as follows: structure "means any man- made object which is intended to remain in

place ...", and vessels are specifically excluded from the definition of a structure unless thdy

are "permanently fixed". (Ex. 23,310 CMR 9.02).

Boats stored seasonably within the easement area are not 'opermanently fixed" in place

and therefore do not arise to a structure as that term is used in the CMR. BLM argues that in

light of the indisputable evidence that BLM property was to be developed as a marina from the

initial concept in 1986, including certain language in the easement itself, the CMR regulations

pertaining to marinas are the most logical place to look for guidance as to what the term

'ostrlrch.re" means as used in the context of the visual easement over the marina,

Likewise, LSP failed to offer any evidence as to the elevations of the building roofs on

the club house and the guard's shack which LSP claims are in violation of the visual easemedt.

The two buildings are situated on pilings over the water. LSP needed to prove three things in

order to be successfirl in its claim: (l) establish MSL; (2) establish the height of each roof top as

being greater than 19 feet above MSLI and (3) establish that the two buildings are in fact

16

situated on Lot 3 and within the easement area. LSP failed to address any one of these three

elements and thus failed to meet its burden of proof. It is also evident from Exhibit E of LSPIs

complaint that the "Guard Shack" is outside of the Visual Easement.

(ii) Non-Exclusive Easement

LSP has the benefit of a non-exclusive easement over an arca 20 feet wide and running

parallel to the common property line between LSP and BLM as shown on a sketch attached to

the grant of the easement. (Ex. 5). The hand sketch does not identiff any existing conditions

from which the Court can locate buildings, walls, property lines, topography, elevations or other

physical features of the land. i

The easement as originally drafted was subsequently modified to eliminate LSP's right

for construction and maintenance of a public walkway and bicycle path within the easement

area. The modification reduced LSP's easement rights to "construction and maintenance of

drainage systems and for construction and maintenance of a sloped, graded erosion and flood

protection barrier". (Exs. 5 and 6). The easement by its terms is non-exclusive; that is, BLM

may use the easement area so long as such use does not interfere with LSP's exercise of its

rights. (Ex. 5).

BLM argues that to the extent the retaining wall it constructed is within the 2O-foot

non-exclusive easement area, the wall, and the area above it, acts as a sloped, graded erosion

and flood protection barrier and adequately addresses the rights of the dominant estate.

Accordingly, BLM argues it has not interfered with LSP's rights under the easement. Also,

t7

BLM argues that LSP offered no evidence that it (LSP) ever took any steps to ooconstruct" a

sloped, graded erosion and flood protection barrier. Quite to the contrary, LSP cut into the

embankment when it added onto the retaining wall originally built by BLM in front of buildings

11 and 12. LSP did exactly what it now claims BLM is prohibited from doing, that is, build a

retaining wall as an acceptable replacement for sloped, graded erosion and flood protection

barrier. LSP, having neglected to exerriise its right to construct a sloped, graded erosion and

flood protection barrier, except for the retaining wall it constructed as noted above, should not

now have veto power over the mailler in which BLM uses the non-exclusive area so long as the

retaining wall serves the purposes stated in the non-exclusive easement.

At trial, LSP's evidence relative to the wall was limited to the 630+l- feet of the

retaining wall at the southerly end of BLM's property. As to the drainage system, it offered no

evidence from which the Court can conclude that BLM has interfered in any way with its

drainage system by constructing the retaining wall or in any other manner. i

LSP's challenge to BLM's right to build a retaining wall within the 20 foot non-

exclusive easement area was not raised until it amended its complaint in 2010, after the

retaining wall was fully constructed.

(iii) BLM's Counterclaim for Trespass

BLM has pleaded in its answer a counterclaim against LSP claiming trespass upon

BLM's property as a result of encroachments by LSP's fence, porch overhang at Building 10,

and a concrete step plus two concrete pads at Building 11. All of the encroachments are

t8

depicted in Exhibit 43, entitled o'Plan of Land Showing Encroachments From The Landing at

South Park Over Borden Light Marina Property in Fall River, Massachusetts, Scale 1" : 60'

Date: october 29, 1999, Mount Hope Engineering, Inc. 163 G.A.R. Highway, Swansea, MA

02777".

LSP offered no testimony to rebut Exhibit 43 or the testimony of Mr. James Hall, whp

testified that, unlike other plans, Exhibit 43 was prepared based upon a field survey for the

purpose of depicting LSP's encroachments onto BLM property.

TV.APPLICABLE LAW

"An easement is by definition a limited, nonpossessory interest in realty." M.P.M.

Builders" LLC v. Dwver. 442 Mass. 87,92,809 N.E. 2d 1053 (2004). An easement can be

either affirmative or negative. Whereas an affrrmative easement permits one to enter upon and

use land in possession of another for a particular pu{pose, "[a] negative easement consists solely

of a veto power. The easement owner has, under such an easement, the power to prevent the

servient owner from doing, on his or her premises, acts that, but for the easement, the servient

owner would be privileged to do." Patterson v. Paul. 448 Mass. 658, 663,863 N.E. 2d 527

QllT(quoting 4 R. POWELL, REAL pnOpgnrY $4.02121[c], at 34-16(M. Wolf ed. 2000).

Thus, a negative easement operates as a restriction on land. Id. At 662-663.

It is a long-established rule in the Commonwealth that the owner of real estate may

make any and all beneficial uses of his property consistent with the easement. M.P.M.

Builders. LLC v. Dwyer. 442 Mass. at 91. The nature and scope of an easement, and

conversely the parameters of how a servient owner may use his or her properfy, are to be

19

construed in accordance with the intent of the parties to the easement grant as determined from

the words of the instrument creating the easement, as well as the circumstances existing at the

time itwas created. Pattersonv. Paul.448 Mass. 658,665,863 N.E. 2d527 Q007); see also

Dale v. Bedal,305 Mass.102,103,25 N.E.2d 175 (1940); Lowell v. Piper.31 Mass. App. Ct.

225, 230, 575 N.E. 2d Il59 (1991). Generally, however, Massachusetts law disfavors

restrictions on land and *[if the interpretation of a particular restriction] can be said to be

doubtful, then it is a doubt which should be 'resolved in favor of the freedom of land frorn

seryitude." Hemenway v. Bartevian. 321 Mass. 226,229,72 N.E. 2d 536 (1947) (quoting St.

292 Mass. 430,433,198 N.E. 903 (1935).

The burden of proving that BLM has violated the easements at issue in this case rests

squarely on LSP. See Mt. Holyoke Realty Corporation v. Holyoke Realt)' Corporation. 284

Mass. 100, 105, 187 N.E. 227 (1933). Mr. John Keith of Keith development Corp., the entity

that developed the condominiums, prepared the easements. (Tr. Vol. tV 73-74).It is a well

established rule of law that writing is construed strongly against the party who drew it if

ambiguous or uncertain language is used. Bowser v. Chalifour, 334 Mass. 348, 135 N.E. 2d 643

(1956). BLM did not find any case wherein a boat was determined to be a structure, in the

context of a visual easement- or otherwise.

Laches is an equitable doctrine which penalizes a litigant for negligent or willful failure

to assert his or her rights. Valmor Produits Company v. Standard Products Corporation. 464 F .

2d,200,204 (l't Ck. lg72). The equitable doctrine of laches will bar a party from asserting a

claim if the party so unreasonably delayed in bringing the claim so as to cause some injury or

prejudice to the defendant. Polaroid Corp. v. Travelers Indemnitv Co.. 414 Mass. 747,75g-760,

20

610 N.E. 2d 912 (1993), citing Yetman i,. Cilv of Cambridee. 7 Mass. App. Ct. 700,707,389

N.E. 2d 1022 (lg7g). Its presence is ordinarily a deterrnination of fact based on the particular

circumstances of the case. Yetman v. Citv of Cambridge. 7 Mass. App. Ct at 707 (citing

McGrath v. C.T. Sherer Co.. 291 Mass. 35, 59-60 (1935) and Tzitzon Realtv Co. v. Mustonen.

352 Mass. 648, 650 (1967). The doctrine of laches may save a defendant from the expense of

removing a structure built on another's land. Harrington v. McCarthy. 169 Mass. 492,494,48

N.E. 278; Geragosian v. Union Realty Company. 289 Mass. 104,193 N.E. 726 (1935)

The essence of an action of trespass to real property is a showing that the Defenda4t

committed an intentional and unprivileged interference with the PlaintifPs possessory rights.

Prosser and Keeton, Law of Torts, 5'h Ed SI3, pp. 69-70. To establish a prima facie case in an

action in tort for trespass, the Plaintiff must prove the breaking and entering of the Plaintiff s

close. The elements of proof are: l) PlaintifPs possession or right to possession; 2)

unauthorized act or entry by the Defendanf 3) damage. Bishop, Prima Facie Case - Proof and

Defense, 531.21 (4th ed. 1997). Damages are not an essential element of the tort of trespass.

In order to find for the Plaintiff in civil contempt, there must be clear and unequivocal

command and equally clear and undoubted disobedience. Whelan v. Frisbee. 29 Mass. App. Ct.

7 6, 557 N.E. 2d 55 (1990); Larson v. Larson. 28 Mass. App. Ct. 338, 551 N.E. 2d 43 (1990).

Civil contempt proceedings are remedial and coercive and intended to achieve

compliance with court's Orders for benefit of complainant, whereas criminal contempt

proceedings are exclusively punitive and designed wholly to punish. Furtado v. Furtado. 380

Mass. 137,402N.E.2d 1024 (1980).

V. ARGTJMENT

2l

A. BLM'S STORAGE OF BOATS ON ITS PROPERTY DOES NOT VIOLATETHE TERMS OF THE VISUAL EASEMENT GRANTED TO LSP DATEDSEPTEMBER 30. I.986.

The visual easement at issue in this c4se provides:

For a view unobstructed by any structure in the area 19 feet aboveMean Sea Level on the premises...Excluded from the definition ofthe term structure as used in this Visual Easement and expresslypermitted to occupy the area 19 feet above Mean Sea Level on thepremises are pilings, supporting piers and floats, hvac exhaustsand/or intakes which are reasonably screened, trees, shrubbery andpicnic tables.

@x. a). The portion of BLM's property encumbered is described in the easement as

follows: i

A parcel of land in Fall River, Massachusetts, located on thewesterly side of Almond Street, bounded and described as follows,running:

i south 89o 53' 55" West to the Mounti Hope Bay; thence rururing

along the Mount Hope Bay to landnow or formerly of the King PhillipBoat Club; thence running

by land now or forrnerly of KingPhillip Boat Club 96.44 feet; thencerunning

by lot I and lot 2 on the planhereinafter described to the point ofbeginning as herein specified.

Being a portion of Lot #3 on that plan of land entitled: "Division ofLand in Fall River, Massachusetts, belonging to Green River RealtyTrust Scale: l" : 80', Date: July 14,1986, prepared by: Site WorkAssociates, Inc., 251 Bank Street, Fall River, Massachusetts",recorded with the BristoliCounty Fall River Registry of Deeds inPlan Book 79, Page 80, as deeded to Grantor by Instrument No.15885 recorded with said Registry of Deeds on October 1, 1986.

WESTERLY:

SOUTHWESTERLY:

EASTERLY:

NORTHEASTERLY:

22

That portion of Lot 3 encumbered by the visual easement can be identified as that part

of Lot 3 lying between an extension of LSP's northern properly line in a westerly direction S.

89o 53' 55" West to Mount Hope Bay and BLM's southerly properfy line running N. 89o 59'

10" West for a distance of 96.44 feet. The southerly line of BLM's property and the northerly

line of LSP's property are shown on Exhibit 16. The visual easement is limited to that portion

of BLM's property lying southerly of LSP's northerly property tine. (Ex. 16, Line Table, Line

DA).

Although the language itself is clear, the issue as to what the term "structure" entails and

how it should be interpreted is vehemently contested and is central to this case. Simply stated,

whether BLM can be said to have violated the terms of this easement by storing boats that reach

19 feet above Mean See Level on its own property hinges upon whether a boat constitutes a

Ioostructure." In light of the applicable larr, the language of the easement grant, as well as the

attendant circumstances sulrounding the sarne, this Court must find that a boat is not a

"structure" within the purview of the easement.

The analysis as to whether a particular thing constitutes a "structure" is governed by the

general rules for the interpretation of easements. The Supreme Judicial Court has determined

that "[a]nything 'constructed or built' (dictionary defrnition) is a structure but whether a

particular thing constructed is within the meaning of the word as used in a statute, regulation, or

contract depends bn the context." Scott v. Board of Appeals of Wellesley, 356 Mass. 159, 161-

162,284 N.E.2d 281 (1969) (concluding that a swimming pool was a "structure" for purposes

of the set-back requirements of the Wellesley zoning by-laws, specifrcally noting that it waq a

"large permanent installation").

23

In Sapah-Gulian v. Lomanno, 17 LCR 692 (Mass. Land Court 2009), the Land Court

was faced with the issue as to whether a swimming pool and retaining wall constituted

"structures" prohibited by a particular view easement. In the course of making its

determination, the Land Court considered the definition of the term as set forth in the local

zoning by-laws and Black's Law Dictionary. Id. at 11-14. The Land Court also noted the

divergent Massachusetts case law on whether particular things amount to structures in particular

contexts. Id. at 15, n. 11 (citing Williams v. Inspector of Bldgs. of Belmont,341 Mass. 188,

191, 168 N.E.2d 257 (1960) (finding that a tennis court was not a structure within the meaning

of a local zoning by-law); Millbury v. Galligon.37l Mass. 737,740 (1977) (finding that a

billboard was not a structure in context of the mechanic's lien statute)). Ultimately, the Land

Court determined that the swimming pool and retaining wall were "structures," in that they fell

squarely within the various definitions of the term. Id. at 16. Of particular consequence to the

Land Court was the size and permanence of the improvements. Id.

Other jurisdictions have likewise sought to interpret the meaning of the term "structure"

as used in restrictive covenants and easements. See e.g., Paye v. City of Grosse Pointe, 2i1

N.W. 826, 827 (Mich. 1937); Stewart v. Welsh, 178 S.W.Zd 506,508 (Tex. 1944); Conrad v.

Boogher,2l4 S.W.211 (Mo. App. 1919). InLeavittv. Davis, 153 Me.279, 136 A.zd535

(1957), the Supreme Judicial Court of Maine was called upon to interpret a restrictive covenant

that prohibited structures on a piece ofproperty so as to preserve a view to the ocean from the

property behind it. The pertinent terms of the covenant provided:

. . . and the said grantors hereby covenant and agree with the saidgrantee that upon the parcel of land lying in front of said lotNinety included between Bay View Avenue, and the sea, and theside lines of said lot Ninety produced to the sea, they will erect ormaintain no buildins or structwe of such a character as to

24

intemrpt or interfere with'the view over said parcel from said lotNinety.

Id. at 536. The owner of the servient properfy had been using his property as a public parking

lot and the issue before the court was whether parked cars or buses constituted "structures"

under the covenant. Id. at 536-537. The court determined that they were not, "[t]he vehicles

are not buildings, nor do they have the characteristic pennanency which we associate with

structures." Id. at 537. The court went on to state that "[a] restrictive covenant ought not to be

extended by construction beyond the fairmeaning of the words," Id.

In the case at bar, a boat shouldinot be considered a structure prohibited under LSP's

visual easement. The terms of the easernent provide insight into the parties' intent involving its

grant. The document preserves "a view unobstructed by any structure in the area 19 feet above

Mean Sea Level on the premises . . . ." (Ex. a). Although the term "structure" is not

affirmatively defined within the easement itself, a list of items is set forth and specifically

excluded from the definition, namely "pilings, supporting piers and floats, hvac exhausts and/or

intakes which are reasonably screened, trees, shrubbery and picnic tables." Admittedly, this list

does not specifically exclude a boat from the definition of structure. But this language clearly

illustrates that the parties envisioned that BLM's property would be used for a marina. The

Lunds testified, without any evidence asserted to the contrary, that one of the ordinary seasonal

operations of a marina is to haul vesselsl out of the water, winterize them, and store them untilj

the boating season returns. (Tr. Vol. IVr96-101). Mr. Bouffard's testimony on behalf of LSP,

admitted a familiarity with marina operations, and he specifically acknowledged that while

boats are in storage they are not permanently affixed to the grotrnd. (Tr. Vol. I I40-I42).

There is nothing in the terms of the visual easement to suggest that the list in the visual

easement is complete and exhaustive. The list simply provides specific examples of items

25

usually associated with a marina that rnight typically be considered a structure, and exempts

them from the purview of the easement. j See e.g., Meyer v. Donovan, 9 LCR 302,304 (Mass.

Land Court 2001) (finding that a pier and dock constituted a prohibited structrne under a

restriction); Monday Villas Property Owners Assoc. v. Barbe, 598 N.E.2d 1291,1293 (Ohio

App. 1991) (finding that radio antennas affixed to a condominium constituted a structure under

the condominium association's rules and regulations); Stewart v. Welsh, 178 S.W.2d at 508

(Tex. 1944) (finding that a fence was a prohibited structure under a restriction). It does not

follow that something that is clearly not a structure, for example a boat, would be prohibited

because it was not included in this list. This interpretation is clearly supported by the fact thpt

the items that are listed in the easement are cofllmonly associated with a marina and have an

element of permanence once set in place.,

The notion of permanence being an attribute of a structure cannot be denied. A

structure is defined by Black's Law Dictionary as *(1) Any construction, or any production or

piece of work artificially built up or composed of parts purposefully joined together <a building

is a structure>." BLecr's Lew DIcrtoNARy 1436 (7e ed. 1999). Moreover, as in the Sapah-

Gulian case where the court considered the local zoning by-laws for guidance in determining

the scope of the term "structure" as it pertained to a view easement involving two homes, the

applicable Massachusetts regulations goveming marinas and boatyards is the logical source for

guidance when determining the scope of that term to be applied to view easements overlookirig

a marina. Title 310, Section 9.00 et seq. of the Code of Massachusetts Regulations governs

waterways, including the marina's licensing, and defines a structure as

[A]ny man-made object which is intended to remain in place in,on, over, or under tidelands, Great Ponds, or other waterways.Structure shall include, but is not limited to, any pier, wharf, dam,seawall, weir, boom, breakwater, bulkhead, riprap, revetment,

26

jetty, piles (including mooring piles), line, groin, road, causeway,culvert, bridge, building, parking lot, cable, pipe, pipeline,conduit, tunnel, wire, or pile-held or other permanentlv fixedfloat. barge. vessel, or aquaculture gear.

310 C.M.R. $ 9.02 (emphasis added). (Ex, 23).

Thus, it is not surprising that the idea of permanence factors heavily in the decisions of

Scott v. Board of Appeals of Wellesley, 356 Mass.I59,284 N.E.2d 281 (1969), in which the

Supreme Judicial Court decided that a swimming pool was a "large permanent installation" and

thus a structure under applicable zoning by-laws, and Sapah-Gulian v. Lomanno, 77 LCP. 692

(Mass. Land Court 2009), in which the Land Court, relying heavily on the Scott decision,

determined the scope of a particular view easement. Likewise, in Leavitt v. Davis, 153 Me.i

279, 136 A.2d 535 (1957), the Maine Supreme Judicial Court wholly based its decision thht

automobiles were not structures on the fact that they lack the necessary permanence.

Similar to the automobiles in Maine's Leavitt decision, the boats stored on BLM's

property lack the necessary permanent nature to be considered a structure. BLM's storage of

the boats is largely seasonal and in fact works much like a parking lot. It is important to note

that not one of said boats is permanently affrxed to the land and, therefore, the boats do not fall

within the definition of a structure under the applicable regulations governing licensed marinas,

as well as any common notion of what constitutes a sffucture. See 310 C.M.R. $ 9.02.

The same logic applies to the travel lift used by BLM to lift boats out of the water and

transport them to different locations on BLM's property. The travel lift has four wheels and sis

driven around the marina property in exactly the same fashion as a truck. There is not a single

element of permanency applicable to the travel lift. (Tr. Vol. IV 97) (Tr. Vol. III 136-138).

27

The terms of the visual easement must not be construed so as to include boats within the

definition of "structure." The language of the easement deed itself clearly evidences an

understanding between the parties that the BLM property was to be used as a marina and boats,

and their storage, are inseparable from such a use and were not intended to be prohibited by the

terms of the easement. As set forth above, Massachusetts law preserves the right of servient

properly owners to use their property in whatever lawful way they choose, consistent with the

terms of the easement. M.P.M. Builders. LLC v. Dwyer,442 Mass. at9l. Inthis case the

servient property owner, BLM, is using its property in precisely the way that was originally

contemplated at the time the visual easement was created and consistent with the intent of the

parties thereto.

Clear and convincing evidence of what the parties intended to be a "structure" at the

time the easement was drafted in 1986, and their understanding of that term in 1999, is the fact

that when LSP filed suit in 1999 alleging a violation of the visual easement, it only raised tlie

roof elevations of the two buildings on BLM's property. See Count I of LSP's Complaint,

paragraphs 25-30.It made no claim that a boat is a "structure" as that term is used in the visual

:

easement, despite the fact that BLM was storing boats above 19 feet above MSL prior to 1999.

(Tr. Vol. III 138-140). It is also noteworthy that LSP did not address boats as "structures" in the

2006 Settlement Agreement either. (Ex. 39). It is obvious from the record that that thought did

not occur to LSP until2010.

LSP has not met its burden of proof that a boat is a "structure" as that term is used in the

visual easement. Therefore, BLM's use of its property to store boats 19 feet above the Mean

Sea Level does not violate the visual easement.

28

B. THE ROOF TOPS OF THE "CAPT. E.G. DAVIS BUILDING'AND *GUARD SHACK'' DO NOT VIOLATE THE TERMS OF T}IE VISUALEASEMENT GRANTED TO LSP DATED SEPTEMBER 30, 1986.

LSP seems to have abandoned this part of its case. Although pleaded in its Complaint,

LSP offered no evidence of where the two buildings at issue are situated on Lot 3, or what the

elevations of their roofs are in relation to MSL or 19 feet above MSL. When LSP rested, BLM

moved for a directed finding on this issuq, and the Court reserved its ruling. BLM again moved

for a directed finding at the conclusion of its evidence, and, again, the Court reserved its ruling

pending a decision on all issues heard at fial.l

Having offered no evidence to support the claim that certain roof tops of BLM's

buildings violate the visual easement, judgment must enter for BLM dismissing that portion of

LSP's Complaint with prejudice.

C. BLMOS CONSTRUCTION OF A RETAINING WALL AND SEASONALSTORAGE OF BOATS SEAWARD OF THE RETAINING WALL, ALLWITHIN THE 20 FOOT NON-EXCLUSIVE EASEMENT AREA, DOES NOTINTERFERE WITH LSP'S RIGHT TO CONSTRUCT AND MAINTAIN ADRAINAGE SYSTEM AND A SLOPED, GRADED EROSION AND FLOODPROTECTION BARRIER.I

i

The language in the grant of the non-exclusive easement and the historical development

of the marina by BLM provide clear evidenoe that BLM intended at all times relevant hereto to

use the easement area for marina purposes. The evidence at trial clearly establishes that it has

done so for over two decades by gradually developing its land as a marina in a southerly

direction along the common property line with LSP. Notice of its intention to do so is

indisputable based upon documents recorded with the Bristol County Fall River District

Regisky of Deeds. @xs. 1,2,4 ,5,7,9JAJ1,12,13 and l4). The photographs taken between 1986

29

and 2009 provide conclusive, uncontroverted physical evidence of the existing conditions in

1986 and in 2009, and how they changed during that time frame. @x. 3a). BLM has pleaded

laches, estoppel and waiver as defenses. It took 23 years to build the marina as it exists today,

and but for the litigation commenced in 1999, which for all practical purposes was abandoned

by LSP as of May 2000, LSP has sat on its rights and watched BLM expend its time, effort and

money to build the retaining wall as an integral part of the marina. To complain now about the

use of the easement area for marina purposes is the epitome of inequity, and barred by the

defenses raised. i

In addition, it is significant to point out that when LSP filed suit in 1999, the action

complained of was not the construction bf *re retaining wall within the 20 foot non-exclusive

easement area, but rather the storage of boats on the top and sides of the bank. The importance

of this point is the when the Court interprets the easement, it must attempt to ascertain the intent

of the parties to the easement when drafted. When suit was filed in 1999, a large portion of the

retaining wall was already constructed, yet LSP did not challenge BLM's right to build the wall.

It did not do so until it amended its complaint in 2010. Therefore, in addition to the laches

argument, it is BLM's position that LSP's omission to challenge the retaining wall in 1999 is

due to LSP's understanding that the non-exclusive easement allows the marina to use the 20

foot easement area for marina prrrpor"r,,including building a retaining wall, an understanding

evidenced by its actions until it concocted its present argument in 2010 that the retaining wall

violates the easement. The record in this case clearly supports this conclusion as to LSP's

understanding of BLM's right to build a retaining wall as part of its marina operations. LSP

offered no evidence of an undersknding to the contrary. Additional evidence of LSP's state of

mind is the 2006 Settlement Agreement which provides for construction of a retaining wall to

30

i

within l0 feet of LSP buildings and pool. (Ex. 39). In fact, LSP did not offer any evidence at

trial from which the Court could conclude that the original intent of the parties to the easement

was consistent with LSP's position in 1999 or 2010. Having failed to offer any such evidence,

LSP has not met its burden of proof. LSP's emphasis at trial was BLM's activities in 2008 and

2009 and how it effects the individual board members. rather than LSP as a.whole.

BLM does not contest LSP's right to challenge in the appropriate forum the construction

methodology employed by BLM to build the wall; that is, its structural integrity should LSP

choose to do so.3 BLM argues that the issues now before the Court are whether or not the

language of the non-exclusive easement allows the construction of a retaining wall within the!

easement area and the use of part of the easement area for marina related pu{poses, and not the

structural integrity of the wall. A claim of negligent construction is not within the jurisdiction

of the Land Court under M.G.L.A. c.185; Sec. 1(k) as there is no underlying dispute concerning

a proprietary interest in land. The property lines delineating ownership and the location of the

easements are not in dispute. Therefore, there is "no right, title or interest in land" within the

meaning of the statute. Shepoard v. Lansone, 16 LCR 155, 156157 (2008).

BLM maintains ttrat it has this right to build the retaining wall within the non-exclusive

easement area, and to use the non-exclusive easement area for marina purposes. Specifically,

the detailed and comprehensive testimony of Dr. Peter Rosen, Ph.D., Coastal Geologist,

supports a finding that the retaining wall accomplishes what LSP is entitled to under the no[-I

exclusive easement; that is, it provides:a sloped, graded erosion control and flood protection

barrier. BLM argues that a retainingi wall exceeds the effectiveness of the pre-existing

t BLM filed a Motion in Limine that was heard by the Court prior to the start of evidence. The Court ruled on themotion concluding that it would not hear evidence of damage to individual units and reserved its ruling on the

allegation of negligent construction. (Tr. Vol. 123-24).

31

conditions for erosion control and flood protection, and that the area above the retaining wall

continues to be sloped and graded in a manner reasonably consistent with the intent of thp

parties to the easement. In fact, LSP itself built a retaining wall within, or immediately adjacent

to, the 20 foot easement area when it added six feet onto the wall built by BLM in front of

buildings 1land 12.Thatretaining *att,ias modified by LSP, serves as an erosion control and

flood protection barrier in exactly the same manner as the wall constructed by BLM.

BLM also points out that at no time did LSP undertake any action to "construcf' a

sloped, graded erosion control and flood protection barrier and that the pre-existing conditions,

including the earth embankment, were created by BLM in the course of building the marina in

phases. As noted above, when LSP did want to take some action within the 20 foot easement

area, it constructed a vertical retaining wall by adding onto the height of a wall built by BLM.

Having done so, LSP has conceded by its actions the right to build a retaining wall within the

easement area and that such a wall will serve the purposes of the easement. Therefore, it

follows that it is within BLM's reserved rights under the easement to change the existing

conditions by building a retaining wall so long as the rights of LSP are not infringed upon.

ln support of its argument that BLM can build the retaining wall and store boats within

the easement area without interfering with LSP's easement rights, BLM relies upon the direct

examination of Dr. Peter S. Rosen. Ph.D. and the cross-examination of Donald N. Leffort, P'E.

Dr. Rosen has a Ph.D. in marine science with a concentration in geological oceanography and

holds a Master's degree in geology with a specialization in coastal geology. (Tr. Vo. III 184).

He is also a Certified Professional Geologist. (Tr. Vol. III 185). At trial Dr. Rosen was

qualified to render an opinion as a coastal geologist. (Tr. Vol. III 187). Prior to his testimony,

he visited the site on three occasions, [eviewed the Ch. 91 Waterways License documents,

32

historic plans, a range of historic photographs, and examined the nature of Mt. Hope Bay. (Tr.

Vol. III 188-189). Dr. Rosen identified and described the two coastal banks on the BLM

property, explained what a coastal bank is, the different types of coastal banks and the purpose

they serve. (Tr. Vol. III 189). He testified that a coastal bank could be natural or manmade and

could be a vertical wall. (Tr. Vol. III 190-191). Dr. Rosen testified that the coastal bank at issue

in this case acts as a vertical buffer to flooding and flood damage. (Tr. Vol. III 191). Dr. Rosen

walked the upper and lower levels of the retaining wall each time he was there. (Tr. Vol. III

195). Dr. Rosen described the entire length of the retaining wall as the upper coastal bank. (Tr.

Vol. III 196). He described the area off the top of the wall at the upper bank as a grassy slope

extending to the condominium buildings. He described a drainage system and a fairly uniform

grassy slope. (Tr. Vol. III 197). Dr. Rosen testified that a vertical coastal bank, comprised of

concrete, has a low likelihood of erosion, with less potential of erosion on top of the bank due

to a gentler slope causing a lower velocity of backwash. (Tr. Vol. III 199). He defined the

terms "slope" and "graded" (Tr. Vol. III 199-2A0), and he defined a'osloped graded erosion arid

flood protection barrier" as follows:

a. As a coastal geologist, could you tell me what a sloped graded erosion and flood

protection barrier means tti you?

A. A flood protection barrier is some form that retards flooding, elevated water

level. A sloped graded erosion and flood protection barrier means it has slope to

it. It means one end is higher than the other, which can involve any level of

slope, from a very slight increase in elevation to vertical and graded means that

it is a smoothed off, leveled surface on that slope.

(Tr. Vol.III201).

JJ

Dr. Rosen testified that the vertical wall that he observed dwing his site visits provides

erosion control and flood protection for the LSP property, and he described how the wall

accomplishes the protection, that is, he explained the basis for his opinion. (Tr. Vol. III 205-

206). His opinion applied to the entire length of the retaining wall. (Tr. Vol. III 206). He also

testified that a properly constructed retaining wall provides flood protection and erosion control

superior to that of the coastal bank observed in the pictures of pre-existing conditions hpi

reviewed. (Tr. Vol. III 209-210). Dr. Rosen testified that the segmented block wall that he

personally observed on the southerly 650 feet of the site provides flood protection and erosion

control for LSP superior to that which is shown in the photos he reviewed of prior existing

conditions. (Tr. Vol. tV 48).

Mr. Donald N. Leffort testified for LSP as to his opinion of the construction of the

retaining wall. (Tr. Vol. I 169). The Court noted that whether the wall was constructed well or

poorly is really not the critical issue in the case, which the Court identified as how does the wall

affect the erosion and drainage rights of LSP, and the location of the wall within the easement.

(Tr. Vol.I178-179).

He testified that he was retained by LSP to give an opinion on the wall between tJte

south end of LSP's property and the southwest corner of Building 5. (Tr. Vol. I 225). He

testified that segmented walls can be used in proximity to water. (Tr. Vol. | 212). He testified

that he examined about 500 feet of the wall. (Tr. YoI. I 227). Mr. Leffort's opinion as to the

lack of geofabric behind the wall was based upon four eight-inch test holes over a 500 foot

length of wall. (Tr. Vol. I 230). He admitted to having no knowledge as to the length of the

geofabric behind the wall over the remaining 496 feet. (Tr. Vol. 1230-231). He offered no

opinion as to the wall lying north of the southwest corner of Building 5. (Tr. Vol. I231). Mr.

34

Leffort admiued that installing geofabric;is not the only way to stabilize the wall. (Tr. Vol. I

232-234). He also testified that he measured the wall for movement at four different points a

total of 24 times over a three-month period and detected movement of one inch at one point.

The last measurement was in April 2010. (Tr. Vol. I 236-2lS). Mr. Leffort admifted to

rendering his opinion without consideration of prior uses or disturbances of the bank on the site.

(Tr. Vol. I 23S). He testified that photographs of previous conditions of the embankment

showed signs of erosion. (Tr. Vol. II 31-37). Mr. Leffort agreed that given the soil materials

shown in Exhibit 34, Photographs 9, 10, 11, 12,31,37 and 38, a retaining wall would give LSP

greater erosion control and flood protection than what was shown in the photographs. (Tr. Vol.

II 44). Mr. Leffort was not retained as an expert/consultant relative to LSP's drainage system

and, accordingly, offered no opinion on that topic. (Tr. Vol. II 45).

One of LSP's other experts, James Holmes, likewise agreed on cross-examination that a

segmented wall is suitable as a retaining wall in coastal areas, and that he questioned the wall

construction, not the use of a retaining wall as an erosion control and flood protection barrier.

(Tr. Vol. II 139-140). He also only testified as to the block wall at the southerly end of the

property. (Tr. Vol. II 140).

LSP also called Mr. Sterling Wall as an expert witness. His deposition transcript with

Exhibits was marked as Exhibit 30. His deposition testimony focused on the excavation of t$e

coastal bank (Ex. 30 P. 75). He testified that he was unaware of the historical use of the

property as a railroad facility and admitted that a coastal bank may include man-made materials.

(E. 30 P. 75). BLM refers the Court to Exhibit 30 and the objection raised thereon by Attomey

Kevin J. McAllister, who represented BLM at the deposition.

35

Based upon the testimony of both Dr. Rosen and Mr. Leffort, a vertical retaining wall ls

suitable as an erosion and flood protection barrier. The easement, as identified in its caption, is

a non-exclusive easement. The retainingrwall acts as an erosion and flood control barrier. The

area above the wall is sloped away from the LSP property line. It is, or has been in the past,

graded and maintained by LSP. Nothing in the easement gives the residents of LSP the right to

walk within the non-exclusive easement area. Nothing in the easement identifres the slope or

grade to be constructed or maintained by LSP or provides a basis upon which the Court can find

that either the existing slope or grade above the retaining wall violate the language of the

easement.

LSP chatlenges the suitability of a retaining wall to provide erosion control and flood

protection to LSP's property, yet that is exactly what LSP did when it added onto the cement

retaining wall in front of Buildings 10 and 11. (Tr. Vol.I[. 106-107) (Tr. Vol. IV 83-84).There

are no legally tenable grounds upon whioh LSP can argue that the wall it constructed in front of

Buildings 10 and 1l is allowed under the terms of the non-exclusive easement, but the wall as

constructed by BLM is not. Mr. John Lund testified the Keith Development, Inc. constructed

an observation deck within the 20 foot easement. He testified that it was required under the c.

91 Waterways License. (Tr. Vol. IV 85). The observation deck is shown on Exhibit 7, page 12

of 15 as "Overlook No. 3". Also, since building the retaining wall in front of Building 10 and

11, LSP has not exercised the right to construct and maintain a sloped, graded erosion and flood

protection barrier anywhere within the easement area. LSP accepted what BLM built without:

complaint until 2010, a year after it was completed.

Furthermore, BLM has the right to relocate the sloped, graded erosion and floodi

protection barrier so long as it does not interfere with the purpose of the easement. M. P.M.

36

Builders. LLC v. Dwvel 442 Mass. 87; 809 N.E.2d 1053 (2004). In M.P.M. Builders, LLC,

the Supreme Judicial Court adopted the Restatement (Ihird) of Property (Servitudes) $4.8

(2000). In adopting $4.8, the Court held as follows:

We conclude that $ 4.8(3) is consistent with these principals in itsprotection of the interests of the easement holder: a change may notsignificantly lesson the utility of the easement, increase the burden on theuse and enjoyment by the owner of the easement, or frustrate the purpose

for which the easement was creatqd.

M.P.M. Builders. LLC,442 Mass. At 91. @91.

Although the M.P.M. Builders, LLC, Court noted that a servient owner may not resort

to self-help remedies, the evidence in this case is such that the Court can find that as BLM built

the retaining wall over the last two decades, it had good reason to believe that it was doing so

with the assent of LSP. That is a finding warranted by the evidence notwithstanding LSP's

untimely Complaint for Contempt. Based on its actions, LSP as dominant estate owner should

not now be allowed to raise the "self-help" defense to BLM's use of the non-exclusive

easement in an effort to avoid the rule of law established by the SJC in M.P.M. Builders.

As in M.P.M. Bqilders, the deed and grant creating the easement in this case do not

expressly prohibit relocation. Therefore, BLM may relocate the easement at its own expense

provided the change in location does not significantly lessen the utility of the easement,

increase the burden on LSP's use and enjoyment of the easement, or frustrate the purpose for

which the easement was created. ld. at 94. Based upon the evidence at trial, BLM has satisfied

each of the conditions of the Restatement (Ihird) of Property (Servitudes) S4.S(3) (200q.

LSP is seeking a mandatory injunction compelling BLM to remove the retaining wall

and restore the embankment to its prior condition. BLM has raised the defenses of laches ar'rd

waiver. BLM activities have occuned in full view of LSP over a period of more than two

37

decades. LSP, by itself adding onto a retaining wall, has actively participated in the precise

activity of which it now complains.

It is well established that injunctive relief may be refused where the Plaintiffis guilty of

estoppelorlatches. Malinoskiv. D. S.McGrath.Inc.,283 Mass. l, 11, 186N.8.225,(1933);

In the case at bar, LSP, through its Board of Managers, testified that it was aware at all times

that the retaining wall was being constnicted, with each witness claiming ignorance of LSP's

legal rights, despite documents to the contrary. Incredibly, they testified that they believed that

the construction by BLM to be legal because the Lunds told them so. Now, after completion of

the wall, LSP argues it has been advised of its legal rights and seeks removal of the wall.

Removal will be a severe burden on BLM. It will cost a lot of money, cause much

inconvenience, and reduce usable marina space within the non-exclusive easement area. BLM

does not seek to use the doctrine of laches as a sword, which is to gain rights by overburdening

an easement, but rather as a shield to protect it from and avoid an inequitable result.

Although LSP did file suit in 1999 raising issues relative to the roof tops of the Capt. E.

G. Davis building and the Guard Shack buildings, alleging they violated the visual easement

(Cognt I), LSP did not challenge the construction and placement of the retaining wall within the

20-foot non-exclusive easement until it ainended its complaint in October of 2010, a few weeks

before the start of trial. The Amended Complaint in 2010 challenges BLM's construction of

part of the retaining wall between building 5 and LSP's swimming pool in 2000, ten years after

the fact. The Amended Complaint likewise challenges the retaining wall construction in 2008

and 2009, well after ttr. "orlrt*ction

of the wall was completed, and 23 years after the first

retaining wall was constructed within the 20-foot non-exclusive easement area. The case was

38

pending from February 1999 to October 2010 before LSP raised its objection to the retaining

wall as being in violation of the 20-foot non-exclusive easement.

LSP unjustifiably delayed in prosecuting its challenge to the construction of the

retaining wall within the non-exclusive easement area. It was represented by counsel at all

times relevant hereto. It had actual knowledge of the construction activity by BLM, and in fact,

participated in the construction of a portion of the wall and expressed appreciation to BLM for

the construction of another part of the wall by way of a written thank you letter in Octobe{,

2008 and by reference in its news letter of March, 2009. (Exs. 38 and 40). The thank you note

and newsletter both referenced the segmbnted block wall. BLM reasonably relied upon LSP's

implied consent to the construction of the wall as evidenced by the actions of LSP's Board of

Managers. BLM has been prejudiced by LSP's unjustified delay of two decades in challenging

BLM's right to construct the wall.

To the extent that LSP argues that the equitable defense of laches is not available to

BLM because it acted inequitably, that argument must fail. BLM anticipates that LSP will

claim that BLM acted in bad faith by not securing all necessary government permits to