Public Identity and Collective Memory in U.S. Iconic Photography

Post-totalitarian national identity: public memory in ... · Social & Cultural Geography, Vol. 5,...

Transcript of Post-totalitarian national identity: public memory in ... · Social & Cultural Geography, Vol. 5,...

Social & Cultural Geography, Vol. 5, No. 3, September 2004

Post-totalitarian national identity: publicmemory in Germany and Russia

Benjamin Forest1, Juliet Johnson2 & Karen Till31Department of Geography, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755, USA;2Department of Political Science, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A2T7, Canada; 3Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of

London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK

Through a comparative analysis of Germany and Russia, this paper explores howparticipation in the memorialization process affects and reflects national identity formationin post-totalitarian societies. These post-totalitarian societies face the common problem ofre-presenting their national character as civic and democratic, in great part because theirnational identities were closely bound to oppressive regimes. Through a comparison ofthree memorial sites—Sachsenhausen concentration camp memorial in Germany, andLubianka Square and the Park of Arts in Russia—we argue that even where dramaticreductions in state power and the opening of civil society have occurred, a simpleelite–public dichotomy cannot adequately capture the nature of participation in the processof memory re-formation. Rather, mutual interactions among multiple publics and elites,differing in kind and intensity across contexts, combine to form a complex pastiche ofpublic memory that both interprets a nation’s past and suggests desirable models for itsfuture. The domination of a ‘Western’ style of memorialization in former East Germanyillustrates how even relatively open debates can lead to the exclusion of certain represen-tations of the nation. Nonetheless, Germany has had comparatively vigorous public debatesabout memorializing its totalitarian periods. In contrast, Russian elite groups have typicallycircumvented or manipulated participation in the memorialization process, reflecting botha reluctance to deal with Russia’s totalitarian past and a emerging national identity lesscivic and democratic than in Germany.

Key words: Germany, monuments and memorials, politics of memory, public memory,Russia.

Introduction

As much recent scholarship suggests, ‘publicmemory’ develops and solidifies through socialand cultural processes rather than individualpsychology. Societies create ‘histories’ forthemselves through material representations ofthe past in arenas that, in turn, function as

symbols of a ‘people’ or nation (Halbwachs1992 [1951]; Nora 1996; Till 2003). Nora, forexample, describes how self-consciously con-structed commemorative places and events ofmemory (lieux de memoire) in modern France,including archives, parades, books and monu-ments, result from confrontational relation-ships between official and vernacular

ISSN 1464-9365 print/ISSN 1470-1197 online/04/030357–24 2004 Taylor & Francis Ltd

DOI: 10.1080/1464936042000252778

358 Benjamin Forest et al.

memories. In that case, alternative, unsanc-tioned forms of public memory oppose andcontest the dominant ‘official memories’ pre-sented by political elites. We argue that thisdichotomy between official (or elite) and ver-nacular (or public) forms of memory is overlysimplistic. Mutual interactions among multiplepublics and elites, differing in kind and inten-sity across contexts, combine to form a com-plex pastiche of public memory that bothinterprets a nation’s past and suggests desirablemodels for its future. Through an analysis oftwo post-totalitarian societies, Germany andRussia, we argue that even where a dramaticreduction in state power and the opening ofcivil society has occurred, an elite–public di-chotomy does not adequately describe the na-ture of participation in the process of memoryre-formation.

Places of memory typically represent the pastthrough historical exhibitions, sculptures or asfocal points for commemorative events. Theymay be symbolic spaces where officials andother social groups express their contemporarypolitical agendas to a larger ‘public’. The socialand spatial nature of public memory affectsboth symbolic representations and dominantconceptualizations of the nation. We definepublic memory as the cultural spaces and pro-cesses through which a society understands,interprets and negotiates myths about its past;through those processes, dominant cultural un-derstandings of a ‘nation’ or ‘people’ may beformed (Till 1999: 255). Yet there may not beconsensus amongst state and local elite groupsas to how and if these places should be remade,because ‘official’ agendas vary. Further, differ-ent social groups, functioning as distinct ‘pub-lics’ and counter-publics, may interact withofficials or choose other actions that influencethe remaking of these places. As we demon-strate below, public memory is an activity orprocess rather than an object or outcome.1

The process of public memory is especiallyevident during the political changes that ac-company post-totalitarian transitions. A suc-cessful transition from totalitarianism todemocracy arguably requires a public dis-cussion about how a society remembers itsrecent past, including how the previous regimerepressed civil society through fear, silence andviolence. Should such acts be defined as‘crimes’? If so, who is held responsible: individ-uals, representatives of the state and/or societyin general? Such questions are particularlytroublesome in societies in transition, especiallyin those cases where human rights abuses weredenied and (may still be) concealed by stateofficials (Kramer 2001; McAdams 2001). Dis-cussions about ‘crimes’ and responsibility arecentral to the politics of public memory, be-cause national histories are (re)narratedthrough such debates.

For societies undergoing political transition,place-making and memory processes aresignificant spatial practices through which thenational past is reconstructed and throughwhich political and social change may be nego-tiated. There may be practical reasons for stateofficials or groups to publicly acknowledge (orforget) victims of the previous regime and com-municate post-totalitarian principles: commem-oration involves relatively little materialinvestment and does not require most people tochange institutional and everyday practices.Yet the memorialization process is far fromstraightforward. The reasons why a place maybe established and (re)situated through com-memorations or historical narratives may vary,as will the ways such places of memory will beinterpreted and used.

The national and international contexts ofpublic memory in any given society also haveprofound influences on the negotiation anddefinition of places of memory. In this respect,Germany and Russia offer striking contrasts. In

Post-totalitarian national identity 359

comparison to Russia, Germany has had along-standing history of addressing and com-memorating the crimes and victims of NationalSocialism through various venues (war tri-bunals, de-Nazification policies, political edu-cation programmes, museums at historiclocations, memorials and so on). These at-tempts were uneven in the divided Germaniesfollowing the Second World War and haveremained so since unification, resulting fromboth international coercion and in response tolocal and national popular protests (Fulbrook1999; Herf 1997). Although problems, contra-dictions and silences remain in the post-unification process of public memory (Doddsand Allen-Tompson 1994; Smith 2000), Ger-many has had relatively open and vigorouspublic debates about its totalitarian periods,including the German Democratic Republic(GDR) past. In contrast, the most powerfulRussian elite groups have typically circum-vented or manipulated public participation inthe memorialization process since 1991,reflecting both a reluctance to deal with Rus-sia’s totalitarian past and an emerging nationalidentity less civic and democratic than in Ger-many.

In this article, we first review the connectionbetween place and public memory, arguing thatthe specific nature of this relationship is es-pecially important in understanding nationalidentity formation in post-totalitarian regimes.The article then examines three case studiesfrom Germany and Russia. We first considerdebates over the renovation of the Sachsen-hausen concentration camp memorial in theformer GDR. In Russia, we examine place-based memory and forgetting at LubiankaSquare (headquarters of the Soviet and nowRussian secret police) and the Park of Arts(where several significant Soviet-era statuesfound new homes after their removal fromplaces of honour in Moscow). We conclude

with a discussion of how the nature of partici-pation in public memory is fundamental to there-presentation of national identity and mem-ory in post-totalitarian societies.

Place, public memory and post-totalitariansocieties

What is required for a society to confront ashameful past? Should a new regime memorial-ize past acts of state-perpetrated violence andinjustice as part of its heritage, and if so how?How should the past—the memory of the vic-tims, the acknowledgement of ‘crimes’, and theconfrontation of social responsibility—be rep-resented and remembered? While Germanshave long rigorously debated and negotiatedsuch questions as a consequence of the legaciesof National Socialism, other states in transitionhave also begun to explore these difficult ques-tions in recent years.

Central to these public debates have been theprocesses of defining ‘criminal’ acts (in stateand/or international law) and assigning re-sponsibility for such acts. What is the nature ofpast acts and under what jurisdiction (cultural,state, international, humanity) should thesepast acts be tried (if at all)? Questions alsoemerge about individual and societal complic-ity, denial and resistance, which become es-pecially complicated when state officialscontinue to hold positions of power after thepolitical transition. Citizen demands for com-pensation, accountability and mourning forprior acts of state-perpetrated violence mayalso be difficult to adjudicate. In short, thelarger social task of working through the his-tories and lingering spectres of these pasts incontemporary society is far from straightfor-ward (Barkan 2000; Buruma 1994; Nevins2003).

Post-totalitarian societies provide especially

360 Benjamin Forest et al.

good cases for studying the negotiation andreformation of public memory precisely be-cause they must face such questions about pastregimes. Totalitarian regimes differ from auth-oritarian regimes in that they demand masspopular mobilization in support of the state,mobilization that ranges from coerced, to indif-ferently feigned, to genuinely enthusiastic. Eventhough the extent of actual mobilization maybe limited, totalitarian regimes base their legiti-macy on symbolic mobilization; even Fascistdictators claimed to rule ‘in the name of thepeople’ (Agnew 1998). Thus, as Cohen (1985:126) observes in regard to the Soviet case,‘historical justice is a powerful “ethical-moral”idea that knows no statute of limitations, es-pecially when reinforced by the sense that thewhole nation bore some responsibility for whathappened’. Nonetheless, widespread publicparticipation and reckoning with the past didnot simply replace top-down state control ineither Germany or Russia. Indeed, as we dem-onstrate, the transitions had complex and am-biguous consequences for public memory inboth societies.

If post-totalitarian societies choose to ad-dress previous crimes, the process of publicmemory must reconcile collective and individ-ual participation and complicity in ways thatprovide both penitence and catharsis.2 In suchsocieties, the recognition and acceptance of thepast requires public participation for the veryreason that the previous regime excluded the‘public’—in the active, democratic and deliber-ative sense—from state representations of thenation. As a result, dealing with the past afterthe fall of the regime also demands publicparticipation and attracts interest from citizensin uniquely profound ways. Without genuineinvolvement by a range of social groups andcitizens, representations of the past are simplya new form of state spectacle or propagandathat reinforces centralized authority and ex-

cludes democratic participation (cf. Ley andOlds 1988; Thomas 2002). While the politics ofplace-making and memory in public settings(even in democratic states) is always marked bythe spectres of past memorialization practicesthat served to legitimate state power,3 in post-totalitarian societies commemorative genresand representational forms—the monumentalmemorial on a pedestal, the museum-templehousing national collections and victories,officials ceremoniously laying wreaths on na-tional memorial days—may be interpreted bycitizens and others as providing continuity,rather than a break, with state power andsocial relations. Indeed, continuity may some-times be a goal of such practices.

In contrast, widespread participation in mak-ing and remaking ‘public’ places of memorycan be both a means and an end of post-totali-tarian transitions where the past is confrontedand a new civic-democratic society is created.Critical discussion about the multiple meaningsof the forms, functions and locations of publicplaces of memory, as well as the pasts to beremembered, may be a process through whichpast injustices can be confronted to workthrough cultural trauma (LaCapra 1994), andto imagine different futures.

Yet transitions may also result in a crisis ofmemory and representation, and a questioningof normative ‘regimes of place’ (McDowell1999). Societies cannot simply abandon pastcultures of memory or meanings of place.Rather, continuities from past to present andfamiliar narratives of self and belonging fre-quently appear in the discussions on the consti-tution of memory in the media, through legalinstitutions, and local political and culturalpractices. We argue that the political and socialuncertainties that characterize transitions mayin fact encourage a process of bricolage,whereby citizens and social groups use ‘a pas-tiche of materials at hand to create a coherent

Post-totalitarian national identity 361

narrative of tradition, memory, and history’(Forest and Johnson 2002: 542). In such cases,it may be especially difficult for a society toconfront its recent past, particularly becausethe recent past remains part of the present,creating unexpected and unknown social insta-bilities, and making it more difficult for peopleto imagine possibilities for different futures.

Scholars have identified the ‘invention oftradition’ as a means to provide stability in aseemingly chaotic present (Hobsbawm andRanger 1992). Yet they have not been as sensi-tive to the complex interactions of the range ofparticipants in the process of public memory.Social scientists influenced by Nora (1989) tendto focus on elite roles in public memory forma-tion and reformation, and when they do in-clude citizen participation, they tend to assumeimplicitly a dichotomy between elite/officialmemory, on the one hand, and popular/ver-nacular memory, on the other. For example, inher discussion of concentration camps in Ger-man memory, Koonz (1994: 261) distinguishesbetween official memory (expressed in cere-monies and leaders’ speeches) and popularmemory (reflected in the media, newspapers,oral histories, memoirs and opinion polls), andargues that ‘public memory is the battlefield onwhich these two compete for hegemony’.

While we agree that there are differences inthe outcomes of public memory, the emphasison this official/popular dichotomy results in anincomplete understanding of the process ofmemory. Certainly there are methodologicalreasons for emphasizing official memory, in-cluding the limited nature of archival materialsand documents, and the investment of timeneeded to research contemporary transitions.Nonetheless, the epistemological assumptionsunderlying the official/popular memory di-chotomy also inform how scholars read suchdocuments and practices, and interpret powerrelations. Koonz, for example, while providing

a rich range of representational materials in heranalysis, problematically assumes that ceremo-nial speeches reflect the intentions of those inpower, and that newspaper articles representthe populace. Such an approach implies thatelites constitute a coherent group or that theycan impose their ideological understandings onto seemingly passive subjects through grandiosepublic displays and monumental spaces. Whilethis may be true in certain ways and for certainforms of control, power cannot be conceivedmerely as a directional flow of ruler to ruled, ordescribed simply as repression and domination(Foucault 1977a). Particularly in democratic orquasi-democratic settings, elites may need tonegotiate with diverse centres of power, or mayneed to respond to popular understandings andinterpretations. Even in totalitarian and auth-oritarian regimes, individuals may choose toresist elite interpretations of monumental land-scapes through everyday practices, such as tell-ing jokes (Atkinson and Cosgrove 1998;Hershkovitz 1993; Scott 1985).

At the same time, recent work maintains thedistinction between official and popular mem-ory by assuming a crisis model of modernsociety, nostalgic understandings of the pre-modern and/or romantic depictions of politicalstruggle (Johnson 1999; Legg 2004; Sturken1997; Till 2003). Nora, for example, describesthe disappearance of ‘true’ memory—embodiedin cultural practices situated in milieux, orcontexts, of memory—with the rise of his-tory—self-reflexive acts of archiving and cere-moniously re-enacting the past—through theemergence of modern lieux, or sites, of memory(Nora 1989, 1996). As Legg (2004) argues,Nora’s nostalgia for a time when memory was‘real’ prevents him from critically engagingwith the contesting and heterogeneousclaimants to the idea of the French nation.Nora’s project, continues Legg, mourns for theFrench nation, or at least the ideal of a time

362 Benjamin Forest et al.

with coherent state power as opposed to apluralistic nationhood. Further, Johnson (1999)argues that Nora’s temporal framework treatsspace as epiphenomenal to the process of his-tory.

Scholars who take seriously the ‘voices frombelow’ and what Foucault (1980) called ‘subju-gated knowledges’ into the analysis of memorypractices tend to focus on acts of resistance andthe creation of ‘alternative’ places of memoryin ways that also maintain the official andpopular memory distinction (Bal, Crewe andSpitzer 1999; Davis and Starn 1989; Gillis1994a). Gillis (1994b) delineates a historicalprogression from pre-national to national topost-national phases of commemoration, wherein the final phase, social groups challengingelite and official depictions of national historyhave severed the ideological coherence betweenthe nation and the state. Within this postmod-ern phase of commemoration, scholars oftentheorize alternative sites of memory as venuesof resistance that challenge exclusive and total-izing national narratives, such as Young’s(1993) counter-sites of memory by Germanartists. Such alternative places are theorized,following Foucault (1977b), as popular sites of‘countermemory’ defined in terms of their chal-lenge to official and elite commemorative prac-tices.

This analytical emphasis on resistance andopposition simplifies the agendas of variousindividuals and groups who may, at times,work together to create alternative or subalternvenues of memory (Frazier 1999). FollowingPile (1997) we argue that the underlying as-sumptions about the domination–resistancecoupling are questionable (cf. Abu-Lughod1990; Sharp, Routledge, Philo and Paddison2000). Social groups historically have interactedwith officials to establish state venues of mem-ory; officials and elites may also play significantroles in the constitution of alternative places.

Further, as Sturken (1997) demonstrates, not allplaces that result from this entangled process ofmemory are necessarily political, and warns ofthe implicit romanticization of Foucault’s con-ception of popular memory.

Ultimately, the elite–public dichotomy is lim-iting because neither category is conceptuallyor politically coherent. Local, national andeven international officials, politicians andother elites may have very different ideas ofwhat places of memory mean, what forms theyshould take, what pasts should be remembered(and in whose name) and what symbolic mean-ings these places should communicate to alarger audience (other officials, locals, nationalsor tourists). They may have different agendasfor these places, and may compete with eachother for control over monument sites, leadingto ideological conflict or incoherence (Agnew1998; Forest and Johnson 2002).

Likewise, there is seldom a coherent ‘public’or populace. Rather, there are many publics,sub-publics and counter-publics, each possess-ing distinct political agendas, access to re-sources and authority, and understandings ofplace (Fraser 1990). Their conceptualizations,uses, experiences and understandings of specificplaces of memory may differ sharply dependingupon their social positions and needs in thepresent and projected future. As the case stud-ies below demonstrate, at certain momentssome publics enjoy greater support, resourcesand access to authority than others, and thusmay actively change landscapes; at other timesthese publics are excluded (by state officials,the media or other actors) in various realms(Staeheli 1997). Further, while some publicsmay engage in passionate conflicts with localand national authorities over the politics ofmemory, in other circumstances many peopleare simply indifferent to these monumentalconflicts.

In short, public memory is a political process

Post-totalitarian national identity 363

that both creates and responds to power rela-tions and identities. At the national scale, elites,publics and public spheres are dynamic, mul-tiple, and intersecting social and spatial cate-gories that cut across and through local, urban,regional and international affiliations andpower relations. Consequently, studies of pub-lic memory require nuanced understandings ofthe complex relationships among these unstablecategories and social groupings that are con-tinuously created and recreated through place-making, social memory, and their relatedmulti-scaled and shifting configurations ofidentity and belonging.

Place and public memory in Germany

Unlike other countries undergoing the tran-sition from East Bloc satellite state to Westerndemocracy, in Germany the history of the GDRis linked to the history of Germany’s othertotalitarian state, the Third Reich. Indeed, thevery existence of the GDR was a direct legacyof National Socialism; after the end of theSecond World War, Germany and Berlin werepartitioned and occupied, and later divided intotwo states that came to symbolize a larger ColdWar conflict. Not only did the National Social-ist past continue to haunt the new Germany, sotoo did the ways that the past was rememberedand forgotten in the Cold War period (Herf1997). These hauntings were materialized in the‘New Berlin’ and Germany through the estab-lishment of new places of memory and theremaking of GDR commemorative sites, in-cluding sites of National Socialist violence(Habermas 1997; Huyssen 1997; Till forth-coming).

Contemporary German discussions about theGDR totalitarian past were unique in anotherway: they were tied to Western narrativesabout ‘winning’ the Cold War, of ‘good’ tri-

umphing over ‘evil’. No other state so directlyaddressed Cold War narratives of victory whilesimultaneously working through a totalitarianpast. Following unification, the workings of theGDR regime were interrogated through legaltrials of leaders and border police, and federalinvestigative commissions, a process based inpart on Germany’s experience dealing with theNational Socialist past (Deutscher Bundestag1994). This process included scholarly researchand discussions over which public places ofmemory in the former East should be closed,reformed or left open. Nonetheless, a relativelyblack-and-white representation of the GDRregime emerged to replace more nuanced un-derstandings of East German society that hadbeen prevalent for the previous twenty years(Fulbrook 1997). ‘The new historical picturewhich was presented was one of heroes, vil-lains, and victims: of an evil gang of criminalsat the top oppressing an innocent people be-low, challenged only by a few resourcefulheroes of the opposition’ (Fulbrook 1999: 226).

The post-unification narrative of East Ger-man society drew from the familiar trope of‘Germans as victims’, one dating back to the1930s, if not earlier, that projects responsibilityfor past actions on to an ill-defined evil other(Assmann and Frevert 1999; Marcuse 2001). Inthis new myth, ‘ordinary’ East Germans wererepresented as ‘victims’ of repressive regimesand not held personally responsible for theiractions (and inactions) supporting the statusquo. Dominant cultural narratives also repre-sented the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG)as the ‘natural’ and inevitable model for aunified German democratic state. Although theGerman constitutional mandate required it,there was no renegotiation of the Federal Re-public’s Basic Law (similar to a constitution) atthe moment of German reunification. Based inpart on this omission, Habermas (1997) arguesthat post-1990 social memory did not reflect a

364 Benjamin Forest et al.

self-critical re-evaluation of the West Germanstate and political system.

Western mainstream magazines such as DerSpiegel, newspapers like the Frankfurter Allge-meine Zeitung and commentaries by formerChancellor Kohl sent the message that EastGermans needed to work through their pasts inorder to become part of (West) German civilsociety. A problematic understanding that the‘West’ had overcome its National Socialist pastand established a ‘normal’ democracy was im-plicit in this narrative. The numerous radicalright activities that included xenophobic acts,brutal attacks and even murder in places likeRostock and Solingen were represented as anEast German youth problem. Yet evidence indi-cated a more complicated social situation, suchas the activism and support of the radical rightin Western states (including activities by so-called ‘necktie neo-Nazis’) and by West Ger-man voters who supported far right orestablished conservative parties running onanti-foreigner campaigns. Rather than examinethis violence within the shifting social contextsof unification, West German experts and crimi-nologists characterized former GDR citizens asmorally flawed (Horschelmann 2001).

Places of memory, their historical narrativesand their social functions offer venues to ex-plore how (and if) post-unification Germanidentities changed. Some scholars have exam-ined the material erasure and reinterpretationof GDR landscapes of memory in Berlin wherenumerous monuments were quickly torn down,Marxist–Leninist institutions were closed andstreet names previously dedicated to commu-nist fighters changed back to their pre-1933names (Azaryahu 1997; De Soto 1996; Till1996). Activist Western-based groups, such asthe Active Museum of Resistance against Fas-cism in Berlin, argued that getting rid of theGDR past in the material landscape recalledthe ‘forgetting’ of the National Socialist past

after the war, and would only make coming toterms with the GDR past more difficult forfuture generations (Aktives Museum 1990),(Till, personal interviews with Christiana Hossand Martin Becher, Active Museum academicstaff, Berlin, 1997). Yet memorials created bythe East German state located at sites of Na-tional Socialist violence could not simply beshut down. Instead, these places of memorywere renovated and their histories revised toreflect Western standards of pedagogy and his-torical research.

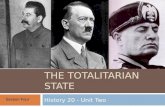

The Sachsenhausen Concentration CampMemorial Museum in Oranienburg, Branden-burg (near Berlin) in the former GDR was onesuch place where post-totalitarian social identi-ties were both constituted and challenged (Fig-ure 1). A range of actors have articulated anddebated questions of social responsibility forthe dark national past through the functions,forms and public meanings of this memorial.Certain aspects of this process have been troub-ling: the continued hegemony of conservativecultural narratives, such as Germans as ‘vic-tims’; the dominance of Western expert opin-ion; and the simultaneous lack of criticalreflection about Western practices of memory.Nonetheless, we interpret the discussions aboutSachsenhausen as a positive result of a long-standing, albeit conflict-ridden, post-war WestGerman politics of memory.

Sachsenhausen was originally built as a‘model’ concentration camp in 1936 and in-cluded a SS-training camp and related labourcamps; during the GDR period some of thesebuildings were reused by the People’s Armyand later the GDR police.4 Before this time,from 1945 to 1950, Soviet occupiers used Sach-senhausen (like Buchenwald) as a ‘SpecialCamp’ to intern Nazi functionaries as well asperceived enemies of the Soviet and emergingGDR states. For ideological reasons, that his-tory of the camp was not officially documented

Post-totalitarian national identity 365

Figure 1 The main gate of Sachsenhausen’s prisoner concentration camp, Oranienburg, August1997. Photograph by K. Till.

in the GDR. In 1961, in response to NationalSocialist camp survivors’ demands, a memorialcomplex was built, and Sachsenhausen, to-gether with Buchenwald (1958) and Ravens-bruck (1959) concentration camp memorials,was transformed into one of the central com-memorative ritual sites of the GDR. A monu-ment, museums and ceremonial eventscommemorated international anti-fascist resist-ance fighters to support the myth of the EastGerman state (Morsch 1996, 2001; Wiedmer1999; Young 1993).

After unification, the new, Western directorsof Sachsenhausen faced the difficult task oftransforming this central symbol of East Ger-man anti-fascist identity into a part of largernational and international networks of histori-cal memory. They used recommendations froma committee of historians and memorial mu-seum experts commissioned by the state ofBrandenburg to evaluate these GDR concen-tration camps (Endlich 1992). According to theexpert commission’s findings, the racist under-pinnings of National Socialist persecution

were ignored because the historical exhibitionsat Sachsenhausen created during the GDR em-phasized the central role of communist prison-ers (including GDR leaders) in anti-fascistresistance. Camp histories emphasized the in-ternational origins of camp prisoners (from 19different countries) and their heroic struggleagainst Fascism, rather than describe the rea-sons why Jews, Sinti and Roma, and othersocial groups, such as homosexuals, were se-lected for genocide or persecution (DeutscherBundestag 1994; Endlich 1992; Morsch 1996).An immediate goal of the new directors, there-fore, was to work with National Socialist pris-oner and survivor groups whose histories hadbeen underrepresented or misrepresented dur-ing the GDR (Till, personal interviews withGunter Morsch, Oranienburg, 1997).

The emergence of new victim groups compli-cated this goal. Following unification, humanremains and mass graves were discovered at theSoviet internment ‘Special Camps’ at Sachsen-hausen and Buchenwald. Directors had to ad-dress the concerns of newly formed Soviet

366 Benjamin Forest et al.

internment camp survivors and victim groupswho demanded recognition of their sufferingand who received local media attention. Ac-cording to museum directors, considerable ten-sion among different victim groups emerged.5

Indeed, at times these groups refused to sit onthe same memorial advisory and consultingboards because National Socialist survivor andprisoner groups felt that the internment campgroups equated their suffering with NationalSocialist persecution.

The new directors pursued a ‘decentralizedapproach’ to reinterpret the artifacts, historicalresearch and memorialization of the GDR pe-riod, and to provide a more extensive represen-tation of the camp’s history under NationalSocialism and for the periods after 1945 (Till,personal interviews with director GunterMorsch, Oranienburg, 1997, 2000). Directorshoped to emphasize the historical significanceof the camp during National Socialism, butalso to include the post-war histories in newexhibits. The decentralized approach does twothings: it offers exhibitions about different as-pects of the camp’s historical layers at particu-lar sites and designates specific areas forcommemorative and mourning activities by dif-ferent victim and survivor groups at differenttimes of the year (Till, personal interviews withGunter Morsch, Oranienburg, 1997, 1999,2000) (also see Morsch 2001). This decentral-ized approach draws from the grassroots his-tory workshop and memorial museummovements that developed in the FRG in the1980s (Rurup 2003; Till 1996), although newhistorical research conducted after unificationhas also had an influence. This approach, how-ever, conflicts with commonly accepted EastGerman, and to a lesser degree West German,understandings of concentration camp memori-als before unification. Memorials in both theFRG and GDR were generally understood asplaces of memory for National Socialist vic-

tims, and in the case of the GDR, for resistancefighters. In the case of Sachsenhausen thismeant that only the triangular portion of theconcentration camp proper was preserved as ahistorical site. When new directors proposedincluding the SS training camp, SS officer resi-dential units and inmate labour camps as partof the concentration camp memorial complex,a number of controversies ensued.

First, the proposal to expand the memorialconflicted with local plans to urbanize some ofthe same area. In 1992–3, the City of Oranien-burg (near the camp site) sought to develop anarea that included the locations of the formerSS troop camp and SS officer residences (StadtOranienburg 1992). The winning design of thepublic competition proposed a multi-use com-plex with residential units, office space, schoolsand a sport centre (Berliner Morgenpost 1993;Der Tagesspiegel 1993; Stadt Oranienburg1992). Although the proposal encouraged theintegration, rather than isolation, of the his-toric area and the contemporary city, campdirectors and other West German memory ex-perts objected, arguing that this was a ‘pro-fanization’ of an important national historicalsite.6 Oranienburg city officials were initiallyconfused about the intense criticisms and de-bates, but subsequently rescinded their initialdecision and selected a proposal by DanielLibeskind that had been awarded honourablemention in the competition. Libeskind’s plan,called ‘Hope Incision’, rejected the premise ofurbanization, and called for a confrontationwith the past through excavations, signs andlandscape designs that mark historic buildingsand significant sites (ForschungsgruppeStadt � Dorf and Schafer 1994; Libeskind 1993;Stadt Oranienburg 1993: 63). These historicalsites provide a dialogue with contemporaryland uses such as schools, an internationalyouth centre, an Institute for Tolerance and anInstitute for Human Rights.

Post-totalitarian national identity 367

These debates included more than historians,urban professionals and artists. Local residentsliving in former SS officer neighbourhoods dur-ing the GDR formed a citizen’s initiative op-posing preservation status of their homes. Theywanted to prevent what they felt was the‘Western’ usurpation of their newly acquiredproperty rights, but also feared that theirneighbourhood would become a neo-Nazi pil-grimage site (Till, personal interview with citi-zen initiative organizer, Oranienburg, 1997).7

In negotiating the conflicts between Westernhistorians and local East German citizens, theLibeskind architectural group became very im-portant. Through discussions with the archi-tects in formal and informal venues (includinglocal pubs and coffee shops), local residentsfinally agreed to place their homes under‘group’ historical preservation provisions,which will limit the changes they can make tothose structures, but still allow the Libeskindproject to be realized (Till, personal interviewwith Mattias Reese, project co-ordinator,Daniel Libeskind Buro, Berlin, 1998).

Although West German directors and mem-orial museum experts, and American–WestGerman architectural teams played aninfluential role in these public debates, the re-conceptualization of Sachsenhausen resultedfrom a complex process of negotiation amongmany actors with different personal and politi-cal interests in the future of this site, includingrepresentatives of various social victim and sur-vivor groups; memorial advisory boards, edu-cators, historians, politicians and memorialmuseum directors; homeowners’ citizen groupinitiatives; historic preservationists; cityofficials; city planners; architects; and others.Debates largely arose in response to memorialpreservation proposals, planning competitions,media coverage about historical and archaeo-logical findings, citizen initiatives and otherrelated contemporary events. Although some

GDR citizens had practical reasons for theirinvolvement, many attended planning boardsand open meetings, discussed plans with archi-tects and preservationists, and were active andinfluential in victim and survivor groups. In-deed, one organizer of a homeowner citizeninitiative group now volunteers at Sachsen-hausen’s main office. By confronting the com-plex histories and perspectives of Sachsen-hausen as a historical place, the groups in-volved found ways to begin working throughpost-totalitarian histories as well as German–German post-war identities.

Place and public memory in Russia

Like Germany, Russia faced an internal debateabout its totalitarian past after the fall of thecommunist regime. While repression and hu-man rights violations had characterized theSoviet regime throughout its history, this de-bate cut most deeply in regard to the Stalin eraand the secret police. Under Josef Stalin, whoruled the Soviet Union from the late 1920s untilhis death in 1953, millions of Soviet citizenswere executed, exiled to labour camps, orotherwise disgraced and traumatized (Conquest1973; Tucker 1990). Millions more denouncedtheir fellow citizens out of fear or desire foradvancement. The state security services, thenknown as the NKVD and already familiar withthe instruments of repression, carried out thispolitical persecution.

Although the Communist Party distanced it-self from much of this legacy during theKhrushchev-era de-Stalinization campaign(when, for example, Stalin’s body was removedfrom the Lenin Mausoleum), this selective re-writing of history occurred without significantpublic participation. The ‘excesses’ of theregime were blamed on Stalin as an individual,even as his bloody efforts to collectivize and

368 Benjamin Forest et al.

industrialize Russia were tacitly approved (Co-hen 1985; Khrushchev 1956). Moreover, thecommunist representations of Stalinist historydid not lead to significant change in the secretpolice apparatus (by then renamed the KGB),which merely scaled back its intimidating activ-ities (Knight 1988). Under Brezhnev the crimesof the Stalin era were once again swept underthe rug, not to surface again until MikhailGorbachev introduced glasnost in the 1980s(Tumarkin 1994).

Gorbachev signalled his willingness to ad-dress the past by releasing physicist and activistAndrei Sakharov from exile in Gorky, encour-aging the ‘rehabilitation’ of individuals exiledor murdered in the Stalin era, and in generalopening up Soviet history to public discussionand evaluation. Human rights groups emergedat this time as well. The most important ofthese, Memorial, aimed to reveal and acknowl-edge the dark past by (among other efforts)erecting a national monument to victims ofpolitical repression (Smith 1996). However, thismovement of memory angered those whoviewed the overall contributions of Stalin andthe secret police in a more positive light (An-dreeva 1990 [1988]; Ligachev 1993). It is notcoincidental, for example, that the heads of theKGB and the Ministry of the Interior playedprominent roles in the failed attempt to over-throw Gorbachev in August 1991 (Daniels1993). These controversial and painful debatesabout the past contributed to the collapse ofthe Soviet regime. When the Russian Feder-ation then emerged as an independent state, forthe first time Russians as a nation had to thinkabout incorporating and recognizing this aspectof Soviet history in their public memory.

Unlike in Germany, though, the question inRussia was not how to recognize and memori-alize the totalitarian past, but whether it shouldbe openly acknowledged as a problem at all(Applebaum 1997; Kramer 2001; Weir 2002). In

Russia, no majority understanding emergedthat saw such public remembering as necessaryfor the future health of the state (Suny 1999).Many Russian political elites had held highpositions in the Soviet party and state appar-atus, and often this translated into a desire todownplay or simply ‘move past’ the past. Simi-larly, much of the population did not see thepast, on balance, as something to be ashamedof, or believed that energy and resources shouldbe invested in public displays of repentance.For example, a survey by the respected agencyVTsIOM found in early 2003 that over half ofRussians polled viewed Stalin’s role in Soviethistory as ‘probably’ or ‘definitely’ positive(VTsIOM Analytic Agency 2003). Indeed, theNew Russian Barometer surveys sponsored bythe Centre for Public Policy at the University ofStrathclyde since 1993 consistently show thatlarge majorities of Russians rate the pre-per-estroika political and economic systems muchmore highly than the current ones (Rose 2002).Moreover, unlike Germany, Russia was notjoining a ‘West’ whose political discourse de-manded a reckoning with the past. As a result,unlike Germany’s Neue Wache memorial, Rus-sia as yet has no recognized central nationalmonument to the victims of political re-pression.

As in Germany, conflict over memory inRussia cannot be described as an elite–publicbattle. Rather, debate embraces majority elitesand publics who prefer to forget, and minorityelites and publics who fight to remember. Inmost cases, however, the process of publicmemory cannot be described as one of nego-tiation and compromise. In the typical pattern,leading political elites erect and remove monu-ments with little effective outside input (Forestand Johnson 2002). If minority elites and publicgroups mobilize to oppose these efforts, ma-jority elites listen but rarely reverse their deci-sions; only reactions from other politically

Post-totalitarian national identity 369

Figure 2 Lubianka Square, Moscow, August 2001. The Solovetskii stone is on the left. The arrowindicates the former location of Dzerzhinskii’s statue in the centre of the square. Photograph by

B. Forest and J. Johnson.

powerful forces prove effective.8 If the minorityopposition is loud enough, majority elites may‘mobilize’ broader public opinion in their fa-vour through commissions, polls and proposedreferenda, using these tools to justify their ac-tions. In addition, particularly in terms ofelites, ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ can refer notsimply to numbers, but to power resources.With former security services head VladimirPutin as president, for example, Russian elitegroups wishing to reinterpret the past in a morepositive light now have a supporter at the top.As the case studies of Lubianka Square and thePark of Arts reveal, the battle over whether andhow to remember the past in Russia remainssensitive and complex, yet far more circum-scribed than that in Germany.

Lubianka Square

The changing face of Lubianka Square inMoscow epitomizes Russia’s conundrums over

recognizing its totalitarian past (Figure 2). Thisis a tale of three monuments—one old, onenew and one not yet constructed—and theimposing headquarters of the state security ser-vice looming over it all. The first monument, toSoviet secret police founder Feliks Dzerzhinskii,stood in the centre of the square until 1991.Since its removal, different elite groups havemade three efforts to restore it. The activistorganization Memorial installed the secondmonument, a small stone from the Solovkigulag, in a park on the square’s edge in 1990.The third, a proposed central national monu-ment to victims of political repression, hasnever been erected despite Memorial’s contin-ued fundraising and lobbying efforts.

For Russians, Dzerzhinskii symbolizes theorder, the terror and the power of the Sovietregime. In August 1991, after the failed coupattempt, crowds surrounded the monumentand tried to tear it down. The Moscow citygovernment, riding the populist wave, acquireda crane and removed it (Luzhkov 1996). After-

370 Benjamin Forest et al.

wards, as disillusionment with the Russian pol-itical, economic and social situation set in, theempty circle of grass where Dzerzhinskii’smonument had stood became a festering sore inthe heart of Moscow. During the 1990s, theconflict over the restoration of Dzerzhinskii—and thus, symbolically, the Soviet past—was aconflict fought principally among elites. In De-cember 1998, the State Duma (Russia’s lowerlegislative house) overwhelmingly passed a res-olution to restore the statue ‘as a symbol of thefight against crime’. The Agrarian Party, Com-munist Party and several smaller parties sup-ported the resolution, while only Yabloko (theparty of liberal, educated urban intellectuals)opposed it unanimously (Tolstikhina 1998).Moscow mayor Yurii Luzhkov forcefully re-jected the resolution, but on the grounds that itviolated the principle of local control. TheAgrarians and Communists proposed a similarresolution in the State Duma in July 2000, butthis time could not muster enough votes to passit (Uzelac 2000).

This dynamic changed again in the yearsafter Putin’s election in 2000, as the presidentsymbolically and rhetorically re-interpreted theplace of the security services and the Stalinistpast in a more positive light (Forest and John-son 2002; Kurilla 2002; Traynor 2000). At thesame time, Putin made strong efforts to re-con-solidate political power in the hands of thepresidency while taming both the Duma andassertive local leaders like Luzhkov. As a result,Luzhkov reversed his position on the Dzerzhin-skii question. When Nikolai Patrushev, head ofthe FSB (the KGB’s successor and current occu-pant of the Lubianka), publicly said in Septem-ber 2002 that he would like to see Dzerzhinskiiback in his former place of honour, Luzhkovapparently interpreted it as a hint from Putin(Abdullaev 2002). Attempting to curry favourwith the powerful president, Luzhkov statedthat Dzerzhinskii’s statue was an ‘excellent

monument’ and that it should be returned tothe square (Filimonova 2002).

While the Communist Party, the FSB andtheir supporters cheered Luzhkov’s proposal,liberal parties and human rights groupsprotested (Abdullaev 2002). The Union ofRight Forces party proposed a Duma resolutioncondemning the idea, which failed for lack of aquorum. Liberal political elites joined humanrights groups for a small protest demonstrationon Lubianka Square, and circulated a petitionagainst the move (Associated Press 2002).Memorial re-released its 1998 statement againstrestoration, but admitted in the new prefacethat restoring the statue ‘is supported byinfluential forces at the top of Russia’s politicalpower structure’ (Memorial 2002). Despite theopposition from minority parties and humanrights groups, a reliable nationwide poll re-vealed that Russian public opinion favouredLuzhkov’s proposal, with 56 per cent support-ing Dzerzhinskii’s restoration, 30 per cent notexpressing an opinion and only 14 per centspeaking out against it (Public Opinion Foun-dation 2002).9

Throughout the debate, Putin himself re-mained silent on the matter. As SakharovFoundation director Yurii Samodurov ob-served, ‘We cannot imagine the German chan-cellor not protesting if the mayor of Berlindecided to erect a monument to the head of theGestapo. Here, it is possible’ (quoted in Rodin2002).10 However, an official statement fromthe Kremlin did come four days afterLuzhkov’s proposal, when deputy chief of staffVladislav Surkov attempted to defuse the ten-sion by stating that ‘today, some are calling forthe restoration of the Dzerzhinskii statue; to-morrow others will demand the removal ofLenin’s body from the mausoleum … both[ideas] are equally inopportune’ (quoted inBirch 2002). As a result, in January 2003 theMoscow City Council finally rejected

Post-totalitarian national identity 371

Luzhkov’s proposal to restore the statue, on thegrounds that it would cause unnecessary dis-cord (O’Flynn 2003). The centre of the squarethus remained empty, its fate (like that of themonument itself) still unresolved.

Given this significant, near-successful effortto restore a central symbol of the totalitarianpast, the second monument on LubiankaSquare—the Solovetskii stone—seems ever-smaller and more incongruous. As its inscrip-tion states, ‘The society “Memorial” wasespecially nominated to provide this stone fromthe territory of the Solovetskii camp and toerect it in memory of the millions of victims ofthe totalitarian regime’. Memorial placed thismonument in October 1990 with the expressco-operation of the Gorbachev regime and theMoscow city government, at a moment when afew powerful elites preferred to remember theSoviet past in order to transcend it. For almosta year, Dzerzhinskii’s statue and the Solovetskiistone stood across the street from each other,as duelling symbols of a state tearing itselfapart. After Dzerzhinskii’s removal, its locationserved as a rallying point for anti-communistprotestors and victims of the Stalinist regime.

Its presence, however, is also a constantreminder of the absence of a third monument,a proposed national monument to the regime’svictims. Memorial has laboured almost alonein this seemingly lost cause to construct acentral symbol of memory and atonement. Thislengthy, so-far futile effort to construct a cen-tral monument contrasts sharply with the rapidconstruction of a prominent state-sponsoredmonument to those who died at Moscow’sDubrovka theatre in October 2002 during ahostage crisis perpetrated by armed Chechenseparatists. Just one year after the attack, Putinpresided over the well-publicized unveiling of alarge monument commemorating the victims(Yablokova and Valueva 2003). As Memorial’swebsite ruefully observes:

Up until now, even after many discussions and two

design competitions, Memorial has not received a

conclusive answer to the question of whether or not

the monument will be established. Or has the

Solovetskii stone … already become this monu-

ment? … The work of recent years demonstrates

that the perpetuation of memory exceeds the powers

of one social organization. (Memorial 2002)

In short, following Memorial’s placement ofthe Solovetskii stone in 1990 and the removalof Dzerzhinskii’s statue in 1991, the transform-ation of Lubianka Square arguably representedthe greatest success in recognizing victims ofthe Soviet state. Yet even this success wasambiguous, both because of the resistance (andapathy) faced by Memorial in its efforts toconstruct a central monument to the victims ofStalinist repression, and because of subsequentattempts to return Dzerzhinskii to his pedestal.As the conflicts over Lubianka Square demon-strate, many Russian elites and publics wouldnot only prefer to forget the injustices of thepast, but to symbolically restore their perpetra-tors to a place of honour.

The Park of Arts

On the evening of 22 August 1991, the Moscowcity government used cranes to remove thestatues of Dzerzhinskii and other Soviet leadersfrom their pedestals in the centre of Moscow.These statues ended up in the Park of Arts(sometimes also referred to as ‘The Park ofTotalitarian Art’). Subsequently, the park cameto play an unusual role in the re-conceptualiza-tion of public memory. Not only did localpolitical elites engage in a concerted effort tode-politicize the statues, but Yurii Luzhkovalso approved the erection of an immense andreviled statue to Peter the Great on the river-bank by the park’s edge. Local elites carried

372 Benjamin Forest et al.

out both the de-politicization of the Sovietstatues and the construction of Peter the Greatwith little public input (Forest and Johnson2002). Yet several public groups actively (andfutilely) protested against the statue of Peterthe Great, while the de-politicization strategymet resistance only from Dzerzhinskii’s sup-porters.

At first, the Soviet statues sat forlorn andunmarked in a weedy corner of the park. But in1996, the Moscow city government formalizedthe display by restoring the statues, installingsmall plaques identifying the figures, and nam-ing the area the Park of Arts. The new parkwas placed under the jurisdiction of Muzeon, asubsidiary of Moscow’s Committee on Culture,and became a display area for contemporaryartistic works. By the summer of 1999, formerSoviet leaders shared the park with a rosegarden, abstract religious art and numerousbusts.

The most important Soviet-era statues hadplaques describing the subject, artist, materialused and where the piece had been displayed.After this description, the plaques attached tothe statues ended with a depoliticizing dis-claimer: ‘It has historical and artistic value.The monument is in the memorializing style ofpolitical-ideological designs of the Soviet pe-riod. Protected by the state’. Characterizingthese statues in historical and artistic termsintended to drain them of contemporary politi-cal significance by politically decontextualizingthe works and emphasizing their alleged artisticvalue. Indeed, the pieces were placed haphaz-ardly and the descriptions never referred tomore than a single statue.

Only the display surrounding Stalin’s statuehad obvious political symbolism, and it isclearly an unusual case. Unlike the other, re-cently removed Soviet-era statues, the Stalinstatue was a casualty of the de-Stalinizationprocess under Khrushchev, and had reportedly

been buried in the sculptor’s garden until it was‘resuscitated’ and placed in the park in 1991(Boym 2001). Ironically, the Stalin statue thusreappeared at the same moment that his leader-ship was most severely called into question.Then, at the height of Luzhkov’s anti-commu-nist sentiments in 1998, the amateur artist Ev-genii Chubarov donated a sculpture groupsymbolizing the gulag to the park, whichpromptly erected it behind Stalin’s statue. Botha de-politicizing description and the stone rep-resentations of the gulag stood together withthe statue, epitomizing the tension over theStalinist past.

Luzhkov’s decision to erect a huge, 60-metre-high statue of Peter the Great nearby moreaccurately indicated how many political elitespreferred to remember the past—by skippingover the Soviet period entirely and glorifyingRussia’s Tsarist period (Figure 3). Although thecity ostensibly held a public competition todesign the monument, Luzhkov’s favouritesculptor Zurab Tsereteli got the commission(Smith 2002). After the statue took up its dom-inating position on the Moscow skyline in1997, two public groups spoke out against it.One group, a coalition of artists led by galleryowner Marat Gel’man, pressed for a publicreferendum on removing the statue. Luzhkovpromised to create a commission to study thematter, but this proved to be merely a stallingtactic. As Smith (2002) notes, Tsereteli’s sup-porters in the political and art worlds thencarried out a massive campaign in the press todefend the sculpture and to publicize the re-ported $12 million cost of dismantling it. Themayor’s efforts to mobilize ‘public opinion’paid off, with surveys revealing that only 12 percent of Muscovites wanted to hold the ‘costly’referendum, and, although many had reserva-tions about the monument’s aesthetic merits, afull 86 per cent spoke against dismantling it(Itar-Tass 1997). Armed with this data, the

Post-totalitarian national identity 373

Figure 3 Peter the Great statue, Moscow, July1999. The Park of Arts lies in the foreground.

Photograph by B. Forest and J. Johnson.

body from his mausoleum on Red Square. Al-though the group did not actually detonate theexplosives, they declared the monument ‘sym-bolically destroyed’ (Kamakin 1997).

Thus, the transformation of the Park of Artsdemonstrates how leading Russian politicianshave often chosen to avoid confrontations withthe totalitarian past. De-politicizing Soviet stat-ues and icons through their placement in thepark represented an attempt to circumvent thekind of vigorous, participatory debates charac-teristic of German public memory. The statuesof Soviet leaders in the Park of Arts remainedin their new places, silent witnesses to a pastthat many Russian elites and publics preferrednot to remember. In addition, Luzhkov’s de-cision to construct the widely detested Peter theGreat statue illustrates how organized publicgroups have often been marginalized in thememorialization process. Although the statuefaced challenges from public groups with verydifferent compositions, ideologies and motiva-tions, Luzhkov and his city government usedtheir influence to marshal the support ofbroader ‘public opinion’ and justify the statue’spresence. The statue remained despite its un-popularity, exemplified by an aborted attemptto blow it up—a far cry from the ‘normal’process of negotiation in Germany.

‘Public’ cultures of memory

As Staeheli (1996) suggests, many scholars tendto assume that a ‘public place’ like a memorialcan be equated with the ‘public sphere’. Yet todo so fetishizes places of memory as objectsrather than ongoing sets of processes throughwhich understandings of political communityand social identity are negotiated. Further, bymistaking the physical existence of ‘publicplaces’ as evidence of a public sphere, scholarsdo not pay enough attention to the ways that

mayor’s commission decided to leave the statuein place.

Not long after this decision, another group‘spoke out’, but in a very different way. In July1997, the obscure ‘RSFSR Revolutionary Mili-tary Council’ placed plastic explosives aroundthe monument and threatened to blow it up inprotest of Luzhkov’s threats to remove Lenin’s

374 Benjamin Forest et al.

place-making processes produce publics. Thethree case studies presented here indicate howpublic memory is a process, rather than ma-terial object or outcome. The comparison ofGerman and Russian public memory since 1989highlights the distinct ways in which multipleelites and publics typically engage in the memo-rialization process, illustrating why studies ofpublic memory should move beyond the simpledichotomy between ‘elite’ and ‘public’.

These examples also demonstrate the com-plex ways various ‘publics’ re-narrate nationalhistory(s) through place-making. Groups mayhave different agendas and conceptions thatsometimes lead to elite–public conflicts, butthat may also engender elite–elite and public–public conflicts. The category of ‘counter-mem-ory’ as ‘resistance’ is too simplistic: a range ofactors and groups may act in ways not necess-arily structured by opposition to state or elitedomination. Furthermore, civic organizationsand interest groups may have highly differenti-ated access to public forums that affect theirpower and influence in the process of publicmemory.

Discussions and events about Sachsenhausen,for example, took place in a range of venues,including the local and national media, artisticpractices, public competitions and protests.While these discussions were at times quitecontentious, overall the process resulted innegotiation and the incorporation of differentperspectives. Participants see the current pro-posal for Sachsenhausen’s future developmentas a compromise solution that incorporatesdifferent layers of history, contemporary socialviews and Western humanitarian (or universal-ist) hopes for the future.

Moreover, given the complex histories andpost-unification debates about Sachsenhausen,some Western museum memorial directors nowargue that different claims to ‘victim’ statusand social responsibility for past crimes should

be evaluated by comparing different total-itarian periods within German history atparticular historic sites. These same directorsmay not have supported such a process in theformer West Germany in the 1980s becausethey may have interpreted the Kohl admini-stration’s cultural politics as an attempt to blurthe categories of National Socialist victim andperpetrator (see Habermas 1989; Maier 1988;Till 1996). Sachsenhausen shows how GDRand even FRG approaches to representingand remembering totalitarian pasts can bereconceptualized.

In the new Germany, emerging practices ofpublic memory may conflict with existing nar-ratives, political cultures and social hierarchiesthat limit the participation and influence ofsome groups—notably former East German cit-izens—but there is still a sense that the ‘nor-mal’ or proper process of memorializationinvolves vigorous public debates and nego-tiation rather than simple top-down, elite-driven decision-making. Civic organizationsplay a central role in these discussions andprocesses, and a broad array of publics success-fully engaged ‘official’ memorial and planningproposals to produce new conceptions of Ger-man identity through a confrontation with thepast.

In contrast, Russian civic organizations havebeen both less interested and less influential inpublicly confronting the more troublesome as-pects of the Soviet past. The relative lack ofinterest—with the notable exception of Mem-orial—reflects a broadly shared opinion thatsuch ‘reckoning with’ or ‘atoning for’ the So-viet past is unnecessary for contemporary Rus-sians and would devalue the more positiveaspects of Soviet history. This indifference doesnot carry over into other realms of publicmemory, however. Peter the Great’s immenseand aesthetically questionable statue provokedintense outcry, both organized and diffuse.

Post-totalitarian national identity 375

Similarly, civic and elite groups have co-oper-ated to erect or restore many cultural andreligious monuments across Russia.

More importantly, though, elites in local,provincial and federal governments have cap-tured the memorialization process for thosepublic sites with potential political resonance.This is not to say that powerful Russian politi-cians ignore popular opinion; indeed, they areattentive to the national ‘visions’ that publicmonuments convey, and manipulate such mon-uments in order to associate themselves withattractive symbols and to bolster their legiti-macy. Rather, as the case studies illustrate,their control over the process contributes tocircumscribing debate over and recognition ofthe more controversial aspects of Soviet his-tory.

This comparative perspective in discussionsof public memory highlights the shifting natureof inclusions and exclusions of various publicsand sub-publics. Conflicts over memorializa-tion in Germany since 1989 show how even arelatively open and participatory culture ofpublic memory still privileges experts in waysthat can exclude or diminish other perspectives.Russia demonstrates, however, that such ex-clusion is relative: post-totalitarian societiesmay develop a top-down rather than a moreparticipatory culture of public memory, ulti-mately placing greater constraints on the waysin which a nation can imagine a new identityfor itself.

Acknowledgements

The authors contributed equally to this articleand are listed alphabetically. The Nelson A.Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College, theAssociation of American Geographers (Anne U.White Grant), the Alexander von HumboldtFoundation and the Office of the Vice President

for Research/Dean of the Graduate School(Grant in Aid) at the University of Minnesotaprovided research support for this article. Wewould like to give special thanks to DerekAlderman, Owen Dwyer and Steven Hoelscherfor their help and encouragement, and for or-ganizing this special issue. Thanks also to RobKitchin, David Sibley and two anonymous re-viewers for their thoughtful comments on ear-lier versions of the article.

Notes

1 We use the term public memory to emphasize thecomplex interactions and tensions within and betweenelite and other social groups. The term public impliespolitical engagement and discussion, whereas culturalmemory need not be political (Sturken 1997).

2 See the voluminous literature about working throughthe past in Germany (Assmann and Frevert 1999;Jaspers 1961; Kittel 1993; Reichel 1995).

3 On hauntings, ghosts, memory and place, see Bell(1997), Gordon (1997), Pile (2002) and Till (forth-coming).

4 Information for this section comes from numerouspersonal interviews, newspaper articles and participant-observations collected and conducted by Till from 1995to 2001. On the history of Sachsenhausen, see Endlich(1992), Morsch (1996), Till (forthcoming) and Wiedmer(1999).

5 Forty-one national associations exist for the pre-1945prisoner groups; 17 are the most important numericallyand have national Sachsenhausen committees. In Ger-many, three Sachsenhausen committees exist (WestBerlin, East Germany and West Germany); other na-tional associations include the Central Council of Ger-man Jews, the Central Council of Sinti and Roma, fourhomosexual organizations and the Social DemocraticWorking Group. The foreign groups, according toMorsch, are unified and have national groups withsubgroups. The prisoner advisory board consists ofrepresentatives from up to twenty groups, includingpost-1945 groups (Till, personal interviews with GunterMorsch, Oranienburg, 1997).

6 Similar debates emerged for development proposals atRavensbruck and Auschwitz (see Charlesworth 1994;Dwork and van Pelt 1996).

376 Benjamin Forest et al.

7 Oranienburg gained a reputation for radical right ac-tivity after unification, and visitors to the camp wereharassed by neo-Nazis, visitor books had anti-Semiticentries and the camp suffered physical defacements,including an arson attack on the so-called Jewish bar-racks in 1992 (Oranienburger Generalanzeiger 1995).

8 One recent exception to this trend was Moscow mayorYurii Luzhkov’s decision to abandon plans to buildnumerous monuments representing characters fromMikhail Bulgakov’s novel Master and Margarita in thewealthy Patriarch’s Pond area. The outcry among localresidents was so great that Luzhkov scaled back theproject considerably, agreeing to erect only a simplemonument to Bulgakov himself (Balmforth 2003).

9 Support in Moscow itself was more mixed, with aVTsIOM poll showing 44 per cent in favour and 38 percent opposed (Saradzhyan 2002).

10 Ironically, there is a memorial space at the formerGestapo Headquarters in central Berlin, called the Top-ography of Terror International Documentation Cen-tre. In contrast, however, this space functions as an‘open wound’ of the city and nation, rather than as amonument to Nazi officers and leaders (Till forth-coming).

References

Abdullaev, N. (2002) Notes from Moscow: the bronzeChekist, Transitions Online, �http://www.tol.cz/look/TOLnew/article.tpl?IdLanguage � 1&IdPublication� 4&NrIssue � 37&NrSection � 17&NrArticle � 7395� (accessed 1 October 2002).

Abu-Lughod, L. (1990) The romance of resistance, Ameri-can Ethnologist 17: 41–55.

Agnew, J. (1998) The impossible capital: monumentalRome under liberal and fascist regimes, 1870–1943, Ge-ografiska Annaler 80B: 229–240.

Aktives Museum (1990) Erhalten, Zerstoren, Verandern:Denkmaler der DDR in Ost-Berlin: Eine dokumen-tarische Ausstellung. Berlin: Aktives Museum und NeueGesellschaft fur Bildende Kunst.

Andreeva, N. (1990 [1988]) I cannot give up my principles,13 March, translated in The Current Digest of thePost-Soviet Press XL, p. 13.

Applebaum, A. (1997) A dearth of feeling, in Kimball, R.and Kramer, H. (eds) The Future of the European Past.Chicago: Ivan Dee, pp. 25–50.

Assmann, A. and Frevert, U. (1999) Geschichtsvergessen-heit-Geschichtsvergessenheit: vom Umgang mitdeutschen Vergangenheiten nach 1945. Stuttgart:Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

Associated Press (2002) Activists protest Dzerzhinsky statueplan, 17 Sept.

Atkinson, D. and Cosgrove, D. (1998) Urban rhetoric andembodied identities: city, nation, and empire at theVittorio Emanuele II monument in Rome, 1870–1945,Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88:28–49.

Azaryahu, M. (1997) German reunification and the politicsof street names: the case of East Berlin, Political Geogra-phy 16: 479–493.

Bal, M., Crewe, J. and Spitzer, L. (eds) (1999) Acts ofMemory: Cultural Recall in the Present. Hanover, NH:Dartmouth College, University Press of New England.

Balmforth, R. (2003) Moscow literary site saved afterresidents protest, Reuters, 1 April.

Barkan, E. (2000) The Guilt of Nations: Restitution andNegotiating Historical Injustices. New York: W.W. Nor-ton.

Bell, M. (1997) The ghosts of place, Theory and Society 26:813–836.

Berliner Morgenpost (1993) Wohnungsbau rund um dasehemalige KZ-Gelande, 17 Feb.: 1.

Birch, D. (2002) Russian nostalgia feeds struggle overmonument to KGB founder, Baltimore Sun, 30 Nov.: 1A.

Boym, S. (2001) The Future of Nostalgia. New York: BasicBooks.

Buruma, I. (1994) The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War inGermany and Japan. New York: Farrar, Straus, andGiroux.

Charlesworth, A. (1994) Contesting places of memory: thecase of Auschwitz, Environment and Planning D: Societyand Space 12: 579–593.

Cohen, S.F. (1985) Rethinking the Soviet Experience: Poli-tics and History Since 1917. New York: Oxford Univer-sity Press.

Conquest, R. (1973) The Great Terror. New York:Macmillan.

Daniels, R.V. (1993) The End of the Communist Revol-ution. New York: Routledge.

Davis, N.Z. and Starn, R. (1989) Memory and Counter-memory, Representations 26: Special Issue.

De Soto, H.G. (1996) (Re)inventing Berlin: dialectics ofpower, symbols and pasts, 1990–1995, City and Society1: 29–49.

Der Tagesspiegel (1993) Abreißen, Fluten oder als Mahn-mal erhalten, 17 Feb.: 1.

Deutscher Bundestag (1994) Bericht der Enquete-Kommis-sion: ‘Aufarbeitung von Geschichte und Folgen derSED-Diktatur in Deutschland’, gemaß Beschluß desDeutschen Bundestages vom 12. Marz 1992 und vom 20.Mai 1992.

Post-totalitarian national identity 377

Deutscher Bundestag, 12. Wahlperiode, Referat Of-fentlichkeitsarbeit.

Dodds, D. and Allen-Tompson, P. (eds) (1994) The Wall inMy Backyard: East German Women in Transition.Amherst: University of Masschusetts Press.

Dwork, D. and van Pelt, R.J. (1996) Auschwitz, 1270 to thePresent. New York: Norton.

Endlich, S. (ed.) (1992) Brandenburgische Gedenkstattenfur die Verfolgten des NS-Regimes: Perspektive, Kontro-versen und internationale Vergleiche. Berlin: EditionHentrich.

Filimonova, A. (2002) ‘Zheleznyi Feliks’ mozhet vernut’siana Lubianku, Izvestiia, 13 Sept.: 21.

Forest, B. and Johnson, J.E. (2002) Unraveling the threadsof history: Soviet-era monuments and post-Soviet na-tional identity in Moscow, Annals of the Association ofAmerican Geographers 92: 524–547.

Forschungsgruppe StadtDorf and Schafer, R. (1994) Prozes-sorientierte Stadtentwicklungsplanung Oranienburg:‘Umgang mit der NS-Vergangenheit:’ 2. Forum Stadten-twicklung Oranienburg am 6.12.1994 in Schloss Oranien-burg: Protokoll. Oranienburg: Stadt Oranienburg.

Foucault, M. (1977a) Discipline and Punish: The Birth ofthe Prison. New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1977b) Language, Counter-memory, Prac-tice. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Foucault, M. (1980) Power/Knowledge. New York: Pan-theon.

Fraser, N. (1990) Rethinking the public sphere: a contribu-tion to the critique of actually existing democracy, SocialText 25/26: 56–80.

Frazier, L.J. (1999) ‘Subverted memories’: countermourningas political action in Chile, in Bal, M., Crewe, J. andSpitzer, L. (eds) Acts of Memory: Cultural Recall in thePresent. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College, UniversityPress of New England, pp. 105–119.

Fulbrook, M. (1997) Reckoning with the past: heroes,victims and villains in the history of the GDR, inMonteath, P. and Alter, R. (eds) Rewriting the GermanPast: History and Identity in the New Germany. AtlanticHighlands, NJ: Humanities Press, pp. 175–196.

Fulbrook, M. (1999) German National Identity After theHolocaust. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gillis, J. (ed.) (1994a) Commemorations: The Politics ofNational Identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UniversityPress.

Gillis, J. (1994b) Memory and identity: the history of arelationship, in Gillis, J. (ed.) Commemorations: ThePolitics of National Identity. Princeton, NJ: PrincetonUniversity Press, pp. 3–26.

Gordon, A. (1997) Ghostly Matters: Haunting and theSociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University ofMinnesota Press.

Habermas, J. (1989) The New Conservativism: CulturalCriticism and the Historians’ Debate. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1997) A Berlin Republic: Writings on Ger-many. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Halbwachs, M. (1992 [1941, 1952]) On Collective Memory.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Herf, J. (1997) Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the TwoGermanys. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard Uni-versity Press.

Hershkovitz, L. (1993) Tiananmen-Square and the politicsof place, Political Geography 12: 395–420.

Hobsbawm, E. and Ranger, T. (1992) The Invention ofTradition. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Uni-versity Press.

Horschelmann, K. (2001) Breaking ground: marginality andresistance in (post) unification Germany, Political Ge-ography 20: 981–1004.

Huyssen, A. (1997) The voids of Berlin, Critical Inquiry 24:57–81.

Itar-Tass (1997) Monument to Peter will remain in place,Nezavisimaia gazeta, 20 May: 2.

Jaspers, K. (1961) The Question of German Guilt. NewYork: Capricorn Books.

Johnson, N. (1999) The spectacle of memory: Ireland’sremembrance of the Great War, 1919, Journal of His-torical Geography 25: 36–56.

Kamakin, A. (1997) Terrorism, Nezavisimaia gazeta, 8July: 2.

Khrushchev, N. (1956) The Crimes of the Stalin Era:Special Report to the 20th Congress of the CommunistParty of the Soviet Union. New York: New Leader.

Kittel, M. (1993) Die Legende von der ‘Zweiten Schuld’:Vergangenheitsbewaltigung in der Ara Adenauer. Berlin:Ullstein.

Knight, A. (1988) The KGB, Police and Politics in theSoviet Union. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman.

Koonz, C. (1994) Between memory and oblivion: concen-tration camps in German memory, in Gillis, J. (ed.)Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 258–280.

Kramer, M. (2001) Why Soviet history matters in Russia,PONARS Policy Memo 183. Center for Strategic andInternational Studies, �http://www.csis.org/ruseura/PONARS/policymemos/pm 0183.pdf� (accessed 3 Jan-uary 2004).

Kurilla, I. (2002) Who is at the gate? The symbolic battleof Stalingrad in contemporary Russia, PONARS Policy

378 Benjamin Forest et al.

Memo 268. Center for Strategic and InternationalStudies, �http://www.csis.org/ruseura/PONARS/poli-cymemos/pm 0268.pdf� (accessed 3 January 2004).

LaCapra, D. (1994) Representing the Holocaust: History,Theory, Trauma. Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell Uni-versity Press.

Legg, S. (2004) Contesting and Surviving Memory: Space,Nation and Nostalgia in Les Lieux de Memoire, paper,Looking Back at Nora conference, Institute of RomanceStudies, London, February.

Ley, D. and Olds, K. (1988) Landscape as spectacle: worldsfairs and the culture of heroic consumption, Environ-ment and Planning D: Society & Space 6: 191–212.

Libeskind, D. (1993) Mourning (conceptual proposal forOranienburg public art competition), 12 February.

Ligachev, E. (1993) Inside Gorbachev’s Kremlin. NewYork: Pantheon Books.

Luzhkov, Y. (1996) My Deti Tvoi, Moskva. Moscow:Bagrius.

Maier, C.S. (1988) The Unmasterable Past: History, Holo-caust, and German National Identity. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Marcuse, H. (2001) Legacies of Dachau. Cambridge: Cam-bridge Univeristy Press.

McAdams, A.J. (2001) Judging the Past in Unified Ger-many. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UniversityPress.

McDowell, L. (1999) Gender, Identity and Place: Under-standing Feminist Geographies. Minneapolis: Universityof Minnesota Press.

Memorial (2002) Eshe raz o pamiatnike predsedateliuVChK-OGPU Dzerzhinskomu, �http://www.memo.ru� (accessed 30 September 2002).

Morsch, G. (ed.) (1996) Von der Erinnerung zumMonument: Die Entstehungsgeschichte der NationalenMahn- und Gedenkstatte Sachsenhausen. Oranienburg:Stiftung Brandenburgische Gedenkstatten und EditionHentrich.

Morsch, G. (2001) Concentration camp memorials in east-ern Germany since 1989, in Roth, J. and Maxwell-Mey-nard, E. (eds) Remembering for the Future: TheHolocaust in an Age of Genocides. New York: Palgrave,pp. 367–382.

Nevins, J. (2003) Restitution over coffee: truth, reconcili-ation, and environmental violence in East Timor, Politi-cal Geography 22: 677–701.

Nora, P. (1989) Between memory and history: les lieux dememoire, Representations 26: 7–25.

Nora, P. (1996) Realms of Memory: Rethinking the FrenchPast, Vol. 1: Conflicts and Divisions. New York: Colum-bia University Press.

O’Flynn, K. (2003) City rejects return of Dzerzhinsky,Moscow Times, 22 Jan.: 3.

Oranienburger Generalanzeiger (1995) Chronik der Er-eignisse seit September 1992, 30 March.

Pile, S. (1997) Introduction: opposition, political identitiesand spaces of resistance, in Pile, S. and Keith, M. (eds)Geographies of Resistance. London: Routledge, pp. 1–32.

Pile, S. (2002) Spectral cities: where the repressed returnsand other short stories, in Hillier, J. and Rooksby, E.(eds) Habitus: A Sense of Place. Aldershot: Ashgate,pp. 219–239.

Public Opinion Foundation (2002) Zagolovok: Vokrugpamiatnika F. Dzerzhinskomu, �http://www.fom.ru�

(accessed 28 September 2002).Reichel, P. (1995) Politik mit der Erinnerung: Gedacth-

nisorte im Streit um die Nationalsozialistische Vergan-genheit. Munich: Hanser.

Rodin, I. (2002) Russia debates restoring KGB ‘Iron Felix’statue, Reuters, 27 Sept.: 3.

Rose, R. (2002) A Decade of New Russia Barometer Sur-veys. Glasgow: Centre for Public Policy, University ofStrathclyde.

Rurup, R. (2003) Netzwerk der Erinnerung: 10 JahreGedenkstattenreferat der Stiftung Topographie des Ter-rors. Berlin: Stiftung Topographie des Terrors.

Saradzhyan, S. (2002) Iron Felix panned by Kremlin, Patri-arch, Moscow Times, 23 Sept.: 3.