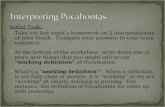

Pocahontas in London - olli.illinois.eduolli.illinois.edu/downloads/courses/2018 Spring/Thames -...

Transcript of Pocahontas in London - olli.illinois.eduolli.illinois.edu/downloads/courses/2018 Spring/Thames -...

Pocahontas in London Tracing a 400-year-old journey across the Atlantic In 1616, Pocahontas caused a sensation in English society when she travelled to London as an ambassador for the Virginia Company. Just ten months later, she was dead, and laid to rest in a Gravesend church. In the 400th anniversary year of her death, Carly Hilts explores how far we can find her presence 1n the material record.

RIGHT In 1617, Pocahontas' visit to England ended in tragedy when she died suddenly of an illness, while still in her early 20s. She was buried in Gravesend, close to where a statue of the young woman stands today.

Four centuries ago, a young woman travelled thousands of miles across the Atlantic to visit London, a heaving city far removed from the

world she knew. She was introduced to society as Mrs Rebecca Rolfe- names she had taken on her recent baptism and marriage- and her family back in America knew her as Matoaka. To us, though, she is best known by her childhood nickname, meaning 'little mischievous one': Pocahontas.

It was the world of commerce that carried Pocahontas from the New

World to the Old: she was brought to England as an ambassador for the Virginia Company and the settlement it had founded at Jamestown, symbolising its success in 'taming' the wilderness. In reality, the colony was struggling financially and eager to attract new investment- something that they hoped Pocahontas' presence might encourage. To this end, she was treated as an important visitor, able to move in the upper echelons of polite society, as befitted her status as the favourite daughter of Wahunsenacawh (also known as Powhatan), foremost

chief of a tributary confederacy of dozens of Algonquian-speaking tribes living in east Virginia. Yet she was also an object of curiosity and condescension, and her adventures would have a tragic end: less than a year after she set foot in England, she was dead, laid to rest among strangers in a Gravesend church.

While Pocahontas' time in England was only brief, the events of her visit still resonate in popular legend. In most of these accounts, however, her own voice is silent. How far can we trace her footsteps in the material record?

SEPTEMBER 2017

• E . ., E . ~ 0

§ t

FIF

Th< wit shE ajc On Co sai an thl Di.

lar ul1 frc th

dt

m OJ t[

p

v

v

Jf

he j

es a

he ;ers

md is it most JWD

tee [?

ER 201 7

FIRST CONTACT The story of Pocahontas' relationship with the English begins long before she arrived on these shores, with a journey in the opposite direction. On 19 December 1606, the Virginia Company's expedition fleet set sail from London in search of land and riches in North America. The three ships- the Susan Constant, the Discovery, and the Godspeed - made landfall in April 1607, reaching their ultimate destination, about 60 miles from the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, the following month.

Here, on the banks of what they dubbed the James River (after the monarch under whose charter they operated), the colonists founded their first settlement. Jamestown was initially a military base- the first women did not arrive until 1608, and this initial wave numbered just two - and it was here that they first encountered the area's indigenous population: Pocahontas' people.

Contemporary accounts describe the young woman as a frequent visitor to the fort. Her interactions with the colonists have been romanticised in later retellings:

ISSUE 330

POCAHONTAS .

her relationship with John Smith in particular has been painted, not least by Disney, as a

LEFT & BELOW The Virginia Company's expedition to the New World, which brought Pocahontas into contact with the English, involved three ships, the Susan Constant, the Discovery, and the Godspeed. The vessels are commemorated in a (1960s) stained-glass window at St Sepulchre-without-Newgate, the London church where one of the most famous colonists, John Smith, was buried in 1631 .

North American Romeo and Juliet tale- despite Pocahontas having been around ten years old when they first met, and Smith's account of her saving his life being more imaginative than factual. Nonetheless, her cooperation and that of her countrymen was vital to the fledgling settlement 's survival.

Yet this friendly contact was not to last: by 1609 relations had soured to the point of open hostilities between the communities, and it was this breakdown that set Pocahontas on her path to England. Matters came to a head when, in 1613, she was lured aboard an English ship, the Treasurer, and taken as a hostage to a new settlement, Henrico. During her captivity, •

c ro

..c ro c

.<; ch

5 I 0.

she learned English, converted to Christianity, and met the recently widowed tobacco planter, John Rolfe, whom she married in Jamestown in 1614. How much of this was by her own volition we do not know, but the union brought an end to the conflict, marking the beginning of a period known as the 'Peace of Pocahontas', and the young convert was soon seized on by the Virginia Company as a perfect poster girl to promote their project back at home.

On this side of the Atlantic, we find little contemporary sign of the expedition's origins. The fleet's departure point, Virginia Quay in Blackwall (opposite the 02 in London) is now a residential area, and all trace of the 17th-century docks have long since vanished beneath later incarnationsalthough the site itself is marked by a stone and bronze monument, built in the 1950s and recently granted Grade IIlisted status by Historic England.

We find far richer remains surviving stateside, however. Since 1994, the Jamestown Rediscovery Project (led by Dr James Kelso) has been excavating the site of the 17th-century settlement, and their investigations

LEFT Although no trace of the 17th-century docks from wh ich the Jamestown expedition set out can be seen today, their departure point is commemorated with this monument at Virginia Quay, east London.

have uncovered a wealth of evidence, from traces of the fort's bastions and palisades to the ditches, buildings, rubbish pits, and graves that its occupants created. The team has also recovered thousands of native artefacts from within the fort, ranging from pottery and projectiles to shell beads and stone axes, all painting a clear picture of how the colonists interacted with Pocahontas' community.

The excavations have also produced tangible evidence of an actual episode from her life: in 2010, the team discovered

the remains of the church, built in 1608, where she married John Rolfe. Five deep postholes, spaced 12ft apart, tally precisely with a contemporary description of the building by the colony's secretary, William Strachey: 'a pretty chapel, in length three score foot'. The location of the finds and the recorded site of the building also match, while further persuasive evidence for its identity comes from the excavated structure's east end. Here, the team found four graves, leading them to interpret the space as the church's chancel, where high-status individuals were interred. It was in this part of the church too that Pocahontas' wedding would have taken place.

ABOVE &LEFT Long-running excavations at Jamestown, Virginia, have uncovered a wealth of 17th-century artefacts made by Pocahontas' people, from mussel-shell jewellery to pots, pipes, needles, and tools. For more information on the project, see www. historicjamestowne. org

SEPTEMBER 2017

ro ·c -~

> c 0 . ., :1 ~ ~ ~ ?::-~ § '6 ID

"' ~ 0 t: ID

~ 0 iii ID t: 0

8 Ui 0 ,._ 0 :r: Cl.

PO Twc Poe Eng her she her her for sor ret1 of I

l_

wa figl Jor cle rec Bis fes Ih otl th. da re~

st;

ISS

wn ed

n lfe. part, :ary 1e 1ey: :ore d the Jatch, for 1ted lffi

to l'S

uals 'the ling

FT

ealth

ts,

nore the !W.

wne.

2017

POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCES Two years after her marriage, Pocahontas was back on board an English ship, and with no account of her thoughts, we can only imagine how she felt to be in similar circumstances to her imprisonment, when the course of her life changed forever. She was bound for England with her husband and new son (Thomas, born 1615), a number of returning colonists, and an entourage of her own people.

Upon reaching London Pocahontas was whisked away to meet influential figures including the Bishop of London, John King. Samuel Purchas, an English clergyman who was present at the time, recorded the occasion, saying that the Bishop entertained his visitor 'with festival state and pompe, beyond what I have seen in his hospitalitie offered to other ladies.' He also notes approvingly that Pocahontas 'carried her selfe as the daughter of a king, and was accordingly respected [by] persons of Honor'.

Pocahontas' perceived royal status granted her access to the

ISSUE 330

r--

-~ .. '

most privileged levels of London society- although she was never formally presented to James I, she did visit his court, attending a royal masque on 6 january 1617. It was an enviable invitation: the Twelfth Night masque was the high point of the court's Christmas season, held in the sumptuous surroundings of •

POCAHONTAS .

TOP In 2010, the Jamestown Rediscovery Project uncovered a series of large postholes, representing the remains ofthe 1608 church in which Pocahontas married the colonist John Rolfe. ABOVE The grand interior of Banqueting House, the only surviving portion of the Palace of Whitehall, where Pocahontas attended a royal masque performed for James l's court.

Banqueting House. Today, the hall is open to the public as the only surviving portion of the Palace of Whitehall (the rest was destroyed in a fire in 1698), and while some of its features - such as its ornate ceiling, painted by Rubens- postdate Pocahontas, visitors can still appreciate the grand space in which she found herself.

It must have been a dazzling experience for the young woman (by now aged around 21 or 22) . Masques combined music, poetry, and dancing, as well as elaborate scenery and dramatic special effects, to tell mythological stories with proroyal propagandist undertones. Held in the huge hall that, on that dark january night, would probably have

LEFT & BELOW Jacobean masques were colourful spectacles, with costumes and scenery often designed by the architect Inigo Jones. Although no such sketches for The Vision of Delight, which Pocahontas watched, are known, Chatsworth House holds a large collection of his designs for other masques, which hint at the elaborate performance that Pocahontas wou ld have seen. For more information about the house and its collections, see www.chatsworth.org

been illuminated by leaping torch flames, it would have been an almost magical sight. We know which masque Pocahontas watched:

+<• -------

it was Ben Jonson's The Vision of Delight,

for which, happily, the entire text survives, as does the setting for the final song (with music by Nicholas Lanier).

Inigo jones, the architect behind Banqueting House, also lent his creative skills to theatrical costume and set designs, and it is likely that The Vision of Delight, like most royal masques of the time, featured his ideas. Unfortunately no designs for this particular production are known, but Chatsworth House in the Peak

District boasts a large collection of jones' sketches for other masques, which give us a good idea of quite what a colourful spectacle Pocahontas would have witnessed.

Again, we have no record of Pocahontas' exact feelings about that night, but she does seem to have enjoyed her time in London. Clues come from a series of letters by john Chamberlain, a London gentleman and irrepressible gossip who corresponded frequently with

SEPTEMBER 2017

his Vis(

lett' ofF anc ofh reh

y.

glir per Ch. soc Poe Ho wo the shE rna see po dif ho jar by far far she wi

set Po co

wl

he

ISS I

for ~own,

ns for that lt the

ttas

L

!1

ER 2017

In a hnus~; \: ln~c 1~' l i,cd ·

p,wahnnla~

fLI5 1)5 lhl l nl' l h._·

his friend Sir Dudley Carleton (1st Viscount Dorchester). Several of his letters from 1616-1617 make mention of Pocahontas' activities in the city, and in one, written towards the end of her stay, he notes that 'she is on her return (though sore against her will).'

Writings like these also allow us glimpses of how Pocahontas was perceived by the English- although Chamberlain, ever-mindful of social jockeying at court, notes that Pocahontas' attendance at Banqueting House went well ('the Virginian woman Pocahontas ... hath been with the King and graciously used, and both she and her assistant well placed at the maske'), her marriage to John Rolfe seems to have been a controversial point. It was not the couple's racial differences that attracted comment, however, but their disparity in status; ]ames I is recorded as being displeased by the fact that Rolfe, a mere gentleman farmer (albeit of a wealthy Norfolk family based at Heacham Hall), should have married a king's daughter without his permission.

Yet while the Virginia Company seems to have been keen to push Pocahontas' elite status, not all were convinced- including Chamberlain, who writes (rather cattily): 'with her tricking up and high style

ISSU E 330

LEFT Pocahontas' health rapidly decl ined during her stay in London, and she and her family soon moved out of the city to rural Brentford. A plaque commemorating her time there was recently unveiled at Syon House.

and titles, you might think her and her worshipful husband to be somebody, if you do not know that the poor company of Virginia [only] allow her four pounds a week for her maintenance'.

PICTURING POCAHONTAS If Pocahontas' funds were so straitened, this might explain why her London lodgings were in such an unglamorous area. For the first part of her visit, she was based at the Belle Sauvage Inn on Ludgate Hill (close to where the City Thameslink station stands today), which historical accounts describe as being plagued by thieves and located rather too close to a pungent refuse ditch. The building no longer survives (one more victim of the Great Fire of London), but in its heyday it was an Elizabethan playhouse and coaching inn. Although performances had long since stopped by the time Pocahontas stayed there (banished to fringe locations like the South Bank after an edict banned theatres from the City in 1594), contemporary descriptions suggest that it had retained its original courtyard layout, with a central square surrounded by covered galleries.

Life in the heart of London does not appear to have agreed with Pocahontas' health, however - the polluted air seems to have affected her breathing, and (perhaps showing the first signs of the respiratory

RIGHT This image is a copy of a portrait of Pocahontas, drawn from life by Simon Van de Passe during her visit to London. Pocahontas' features are surprisingly haggard for a woman still in her early 20s- are these hints of the respiratory illness that would kill her the same year?

POCAHONTAS -

disease, possibly tuberculosis, that is thought to have killed her) she later decamped with her family to a house in Brentford, which was then a rural Middlesex village rather than the built -up London suburb that we see today. Her second home is long since demolished - a Royal Mail sorting office now occupies the spot- but a plaque commemorating Pocahontas' links to Brentford was unveiled on the boundary wall of nearby Syon House earlier this year.

While based in this new location, Pocahontas was visited by her old associate John Smith, and the playwright Ben Jonson whose masque she had attended. This latter meeting may have been in the Three Pigeons, a Brentford inn that] onson is known to have frequented. He later immortalised the episode in his play, The Staple of News, first performed in 1625. In this text, the character Pennyboy Canter delivers the lines: 'I have known a Princess, and a great one, come forth of a tavern .. . The •

f'IIITClltArdkH'O(OIJY 4 7

blessed Pocahontas (as the historian calls her) and a great king's daughter of

· Virginia hath been in womb of a tavern'. Perhaps the most personal piece of

material evidence from Pocahontas' travels, though, is a portrait of her that was drawn from life by Simon Van de Passe, a Dutch engraver based in London. Although no original prints survive, numerous copies were sold and circulated, and many of these are known today. It may be to one of these copies that]ohn Chamberlain refers when he writes in a letter of 'the Virginian woman whose picture I sent you'. Pocahontas is shown modestly but fashionably dressed in the garb of a high-ranking English lady of the time- her fine lace collar, tall hat, and ostrich feather fan would all have been familiar markers of her status and respectability to contemporary society.

Most striking, however, is her face;

}/ ,;.'?T ~ :&:

"~ -1

her drawn features make her look far older than her true age. Is this the haggard image of a woman desperately ill with consumption? If so, it comes as no surprise that the full text of Chamberlain's note about the portrait reads: 'the Virginian woman whose picture I sent you died last week in Gravesend as she was returning home'.

THE LOST GRAVE The end, when it came, was sudden. Pocahontas and her party were on their way back to Virginia, but they only made it as far as Gravesend before she fell dangerously ill. She died aboard ship, and in these final moments at last we hear her voice (albeit filtered through English accounts). In a letter, the newly bereaved John Rolfe records her final words as 'all must die. Tis enough that the child [her son]liveth.'

Pocahontas was buried in StGeorge's

LEFT StGeorge's, Gravesend, built in the 18th century, stands over the site of its predecessor, in whose chancel Pocahontas was la id to rest in 1617. The precise location of her grave is unknown. More information: www.stgeorgesgravesend.org.uk ABOVE The burial register in wh ich Pocahontas' internment is recorded gives her name as 'Rebecca Wrolfe', the name she adopted following her baptism and marriage -yet her identity as a 'Virginia lady' has also been preserved. Her entry can be seen under 21 March, marked with a cross.

Church, Gravesend, on 21 March 1617. Contemporary documents record that she was laid to rest in the chancel, though the precise location of her grave is today unknown. The church burned down in 1721, and although its successor, the present church, was constructed on the same site, its scale and architecture are quite different, and it is not known whether the modern apse overlies the old.

The church's 17th-century burial register does survive, however, complete with the entry for Pocahontas' interment. It reads: ' 1621 March 21. Rebecca Wrolfe, wyffe of Thomas [an error for John] Wrolfe, Gent, a Virginia lady Borne, was buried in ye Chancel!.' Pocahontas may have been laid to rest under her baptismal and married names, but the reference to her as a 'Virginia lady' shows that her new English identity (whether adopted or imposed) had not completely erased her Native American origins. I

Acknowledgements Grateful thanks are due to the Jamestown Rediscovery Project, Chatsworth House, the Institute of Historical Research, and the Reverend Canon Chris Stone of StGeorge's Church, Gravesend .

SEPTEMBER 2017