Peter Furst- Dolmatoff

-

Upload

david-fernando-castro -

Category

Documents

-

view

55 -

download

2

Transcript of Peter Furst- Dolmatoff

Seeing a Culture without Seams: The Ethnography of Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians. by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff; The Shaman and the Jaguar: A Study of Narcotic Drugs among the Indians of Colombia. by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff; Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians. by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff Review by: Peter T. Furst and Jill Leslie Furst Latin American Research Review, Vol. 16, No. 1 (1981), pp. 258-263 Published by: The Latin American Studies Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2503227 . Accessed: 12/01/2013 22:27Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The Latin American Studies Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Latin American Research Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SEEING A CULTURE WITHOUT SEAMS: The Ethnography of Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff PeterT Furstand Jill LeslieFurstState UniversityofNew Yorkat Albany AMAZONIAN COSMOS: THE SEXUAL AND RELIGIOUS SYMBOLISM OF THE TUKANO INDIANS. By GERARDO REICHEL-DOLMATOFF. (Chicago, Ill.: THE SHAMAN AND THE JAGUAR:A STUDY OF NARCOTIC DRUGS AMONG THE INDIANS OF COLOMBIA. By GERARDO REICHEL-DOLMATOFF. (PhilaBEYOND THE MILKY WAY: HALLUCINATORY IMAGERY OF THE TUKANO INDIANS. By GERARDO REICHEL-DOLMATOFF. (Los Angeles, Calif.:

University of Chicago Press, 1971.)

delphia, Pa.: Temple University Press, 1975. Pp. 280. $15.00.) UCLA Latin AmericanCenter,1978. $25.00.)

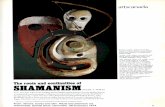

The underlying base ofNative Americanreligion,wroteWestonLa Barre in 1970, was and continues to be even now an essentiallyMesolithictype of Eurasiaticshamanism, originally carriedinto the New Worldby early bands of big-game hunters and food gatherers. Shamanism by definition is inseparable fromthe ecstatic-visionary experience,and it is this, according to La Barre and other recentstudents of the phenomeof sacred hallucinonon, that explains the extraordinary proliferation genic or psychoactiveplants in indigenous ritual,especially in Mexico and parts of South America. No fewer than eightyto one hundred of these botanicalhallucinogens have thus farbeen catalogued, principally by Harvard's RichardEvans Schultes, and more are coming to lightwith each passing year. In any event, La Barre's "shamanistic-ecstatic base" can be identified not only in the religionsof huntersand gatherers, but, of agriculturalpeoples as well, not excluding the great significantly, Meso-American and Andean civilizationsof the pre-European past. If this shamanisticbase was not previously recognized, or continues to be questioned or even rejected, it is because of the mistaken assumption that shamanism is a phenomenon of a "primitive"world, and would thus have to be exclusive to preagricultural societies,particularlythose of northeastern Asia and the Arctic.Indeed, it is oftencoupled with the adjective "simple," the implications being thatshamanism is too archaic, too primitive, or too naive to be associated with complex socioeconomic conditions,or even with tropicalforestor highland agriculture. In fact,judging fromthe sophisticationand complexity of sha258

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEW

ESSAYS

manisticIce Age art, the shamanisticworld view has probablynot been as recent studies of "simple" fortens of thousands of years; certainly, South America or Indian Mexico have shown, it shamanism in northern is in no sense "simple" whereverit survives today in the New World. no one has done more to explore Among modern fieldworkers, interrelationship the complexitiesof thisphenomenon and its functional with the ritual use of sacred hallucinogenic plants than the Austrianborn Colombian anthropologistGerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff.Formerly chairmanof the Departmentof Anthropologyat the Universidad de los is best known to English-speaking Andes in Bogota, Reichel-Dolmatoff readers forbooks on Colombian archaeology and art-Colombia (1965), in the Praeger Ancient Peoples and Places series, followed in 1972 by also published by Praeger-and on San Agustin,A Cultureof Colombia, the intellectualculture of Colombian Indians-Amazonian Cosmos, The He has also published a theMilkyWay. and Beyond Shamanand theJaguar, Indian mythologyand American on South articles number of major symbolism and the use of the hallucinogenic yaje vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) in ecstaticvision quests. Less well known, but indispensable as a source work, is a two-volumeethnographyin Spanish on the first-hand Kogi of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (1950-51), a traditionalindigenous society whose complex religionand temple cult are again the focus of his currentresearch. considers the role Reichel-Dolmatoff In TheShamanand theJaguar, and use of different hallucinogenic plants, including potent psychoas they active snuffs, by South AmericanIndians in general, particularly and functionin the central experience of shaman-jaguar identification But in much of his ethnographicwork, including this transformation. seminal ethnographicstudy of felinesymbolismthat figuresso heavily in the iconography of pre-Hispanic art in Meso- and South America, on the Deand in his earlierAmazonian Cosmos,he focuses specifically sana, a small subgroup of the Tukano, numberingsome one thousand of members,livingmainlyin the dense and humid equatorial rain forest Amazonia. As is oftentrue of names apthe Vaupes, in northwestern plied to tribalpeoples, Desana, a termof apparent Arawakan origin,is wiranot theirown designation; rather,theycall themselvesalternately Sons of the Hummingbird, the pora, Sons of the Wind, or mimi-pora, little bird recognized as mythologicalancestor by all their sibs. The Desana economy is a mixed one of hunting,fishing,and horticulture, but although the products of the hunt make up only a quarter of the theirmen-insist that totaldaily food intake,they-or, more accurately, and horticulture and foremost hunters,and consign fishing theyare first to a farlower place on theirscale of values. The principal products of horticulture are bittermanioc as the basic staple, plantains, bananas, 259

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LatinAmerican Research Review yams, sweet potatoes, pineapple and chili peppers, and it is on these, augmented by fishand game, thatthe Desana rely,notwithstanding the assertionthatthe lifeof the hunteris the only one fitfora man. All this sounds like standard ethnography,with emphasis on in relationto tropicalforest economics and social structure ecology,and ifit were, Reichel-Dolmatoff's place among modern fieldworkers would already be assured. But thereis more, much more, forhe is one of the lamentablysmall handfulof ethnographers who insistthatthe ideology and intellectuallifeof native peoples deserve to be taken seriously-as seriously, indeed, as do the carriers of the culturethemselves-and who recognize not just the decisive role of ideology in the regulation and organization of daily life but the functionalinterrelationship of mental lifewith the environment, whether socioculturalor natural. Equally to the point, in accepting the validityof native ideology and explanation, Reichel-Dolmatoff avoids the pitfallsof imposing Westerncategories,or the fragmented Westernworld view in which these categoriesare sealed offin discrete pigeonholes. (Parenthetically, it mightbe noted that his main informant for AmazonianCosmos,in the course of talking to the ethnographerand explaining his culture to him, himselfbegan to see the inner connections between contemporaryDesana social structure and the originmyths,environment, and hallucinogenicyaje visions in which ancestors,cultureheroes, and events and places of native history reveal themselves and their validityto the participantsin the ecstatic rituals,and came to feel that he himselfwas achieving a deep level of wisdom thathe did not possess at the outset of the relationship.This is an experience other ethnographershave also had with some of their informants.) True, Reichel-Dolmatoff gave colored pencils and other drawing materialsto the Desana and asked them to draw and explain theiryajeinduced visions and certain symbols that apparentlyrecur with some regularity in yaje trancestates,and thathave become an integralpart of the artistic repertoire of the culture.But even though the materialswere of alien origin,the recordingof yaje motifs,alone and in combination, on different flatsurfaces,including the walls of houses, or on pottery vessels, and public discussion of the significanceof these motifs,were well withinthe indigenous tradition; in any event, thisaspect ofReichelDolmatoff'sfieldwork is brilliantly presented,with reproductionsof the native drawingsin fullcolor,in his latestbook, Beyond theMilkyWay. It is art historyof a very different kind, and a major new contribution not only to the growing corpus of authoritative literature on botanical hallucinogens in theirculturalcontextbut also to the study of "primitive" art. Here again, as in his earlierwork, what emerges fromthe writings of Reichel-Dolmatoff is the richness of culture as a whole that by and 260

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEW

ESSAYS

who large characterizedthe published volumes of earlier fieldworkers came to anthropologyfromthe natural and physical sciences, and who of timenor by academic straightwere constrainedneitherby limitations and insatiablycurious. jackets, and who were, above all, respectful work it is a cerIf thereis one problem with Reichel-Dolmatoff's tain sexual imbalance. The intellectualcultureof the Desana sometimes appears Freudian beyond even Freud's fondest dreams, inasmuch as almost everything is sexually-related.But the problemwith this is thata femininepoint of view is singularlylacking. One would like to know, in such sex-charged forexample, whetherthewomen also see everything terms,and what they themselves have to say about the taboos thatare in the taken so seriouslyby the men. Women do not participatedirectly yaje rituals,i.e., they do not themselves drinkthe powerful hallucinoin the yaje visions. It is thus genic brew and thus do not share directly of the the men, not the women, who receive supernaturalconfirmation validityof the culture and its symbols. How does this affecttheirattitudes? One would like to know how the women view the ecstaticvisionaryexperience and to hear this fromthe women's own mouths; through what littlewe get of the women's viewpoint is largelyfiltered or the ethnographer'sobservationsof overtbehavior. male informants This imbalance plagues much ethnographicfieldresearch. It is, in fact,inherentin the practiceof sending studentsof one or the othersex into situations where, as a rule, the female sphere is closed to males, and the male to females. This mightbe correctedif ethnographersgo into the field as male-female teams, because areas normallyclosed to when the invesone sex or the other tend to open up, at least partially, tigatoris perceived as a memberof a familyunit. works in the great These reservationsaside, Reichel-Dolmatoff of anthropology.Above all, he appreciates the role of ideology, tradition or mental life. But forhim it is not just ideology influencingdaily life, but a far more complex process of reciprocal interactionbetween idetrances), enology, mental life (both waking and in ecstatic-visionary the enculturationof the young, vironment, economics, social structure, the arts and crafts, conservationof scarce naturalresources, technology, are not and so on. The implicationis thatwhere these interrelationships recognized, cultureis distorted.This is not to say thatit is wrong per se to focus on one or another aspect-e.g., a marketsystem, or hunting technology.But it must be acknowledged thatin doing so, the aspect so isolated fromthe otherculturaleleselected tends to become artificially ments with which it is interdependentand which, indeed, make it possible to exist in the firstplace. A beautifulexample of this vital interkind of ethnographyis his account, dependence in Reichel-Dolmatoff's in Amazonian Cosmosand elsewhere, of the replenishingof the energy 261

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LatinAmerican Research Review cycleof the naturalenvironment throughthe exchange, in the shaman's hallucinatory yaje trance,of the souls of taboo violators forgame animals belonging to the supernatural"master of animals" of the Vaupes region. The Desana are acutely aware of the danger of overhuntingand seek to assure continued balance between theirneeds and the environmental possibilitiesby supernaturalmeans. Hunting is thus as much a matterof ideological determinants as of economic ones. Undoubtedly, the isolationisttendency and lack of attentionto ideology and religion,and theirimpacton the culturalwhole in much of but of modern ethnography, are the resultnot just of academic training, enculturationfroman early age into-and unconscious acceptance of the values of-a secular and highly technologized society fascinated with economics, innovation, change, specialization, energy input and output, and what has come to be known in social science jargon as "adaptive strategies." Unlike psychoanalysts, who must undergo intense self-examination beforeinterpreting the minds of others,anthropologists, with few exceptions,are ill-preparedby theirtrainingto turn the eye inward and ask the nature and sources of their own preoccupations. Even the simplest and stablest native culturemust have an economic dimension and over millenia it must experience change and innovation. But this is not necessarilythe salient featureor concern of such a culture. On the contrary, the prime concern may be and often is-especially today-the preservationof traditionalways and values and the minimizationof the impact of change fromthe outside, even where such change is seen to offer economic benefits.A friend,the late Eva Hunt, once told us of an experienceamong the Cuicatec of Oaxaca, a people with wide mercantile interests.As she kept asking questions of the women about theirmarketsystemand tradingpatterns,theywould patientlybut insistently reply,"But Eva, that is not important.This is important, writethis down," and proceed to speak of theirbeliefsand, in some instances,of the sacred natureof things. No doubt, Reichel-Dolmatoff's European background has had a profound influence on his concern and respect for native intellectual attainment.In this he is the heir to a long and honorable list of Americanists of European intellectualheritageor education whose major concern has been the ideological universe of the indigenous peoples of the New World: among others, Boas, Kroeber,Lowie, Preuss, Hultkrantz, Schultze Jena,Levi-Strauss, Rasmussen, W. Muller,Wilbert,and some of theirAmerican students come to mind. In the European intellectual tradition,ideas are importantand are capable, like faith,of moving mountains. While the European intellectual tradition is worlds removed fromthatof native Americans,an educational systemthattakes its own ideas seriouslywould betterprepare the anthropologist to take the ideas 262

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEW

ESSAYS

of others seriously as well. In comparison, our own system of higher education stresses method and theory.Is it, then, realistic to expect serious and respectfulconcern with native ideologies and intellectual culture on the order of the contributions of a Reichel-Dolmatoff where the educational system that produced the ethnographerplaces so little value on its own intellectualheritage?How many recentPh.D.s in anthropologyhave read Plato's Republic, or even the major works of the foundersof theirown discipline?SELECTED GERARDO 19501951 1972 1976 1976 1978 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF REICHEL-DOLMATOFF

Los Kogi: Una Tribu de la SierraNevada de Santa Marta, Colombia.2 vols. Bogota. "The Cultural Context of an Aboriginal Hallucinogen: Banisteriopsis caapi." In PeterT. Furst,ed., FleshoftheGods: TheRitualUse ofHallucinogens, pp. 84-113. New York:Praeger. "Desana Curing Spells: An Analysis of some Shamanistic Metaphors." Journal ofLatinAmerican Lore2 (2), pp. 157-219. "Cosmology as Ecological Analysis: A View fromthe Rain Forest."Man 11 (3), pp. 307-18. "The Loom of Life: A Kogi Principle of Integration."Journal of Latin American Lore4 (1), pp. 5-27.

263

This content downloaded on Sat, 12 Jan 2013 22:27:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions