Perceptual Poetics: Carel · PDF fileTwo years later Rudy Fuchs and Jan Debbaut at the Van ......

Transcript of Perceptual Poetics: Carel · PDF fileTwo years later Rudy Fuchs and Jan Debbaut at the Van ......

blending of two mediums not normally associated with each other — one relatively new, high-tech, and viewed on pixelated screens, the other as old as art, poetically intimate, and horizontally oriented because of the flow of pigmented water. Art at the intersections of different mediums is often about the space or state of being “in between”: neither the one, nor the other, yet both, or plural, and more. Balth’s Videowatercolors are the culmination of work in series of four decades. Showing them in relation to these earlier works heightens their depth and visual diversity. MW.

Topicality

Carel Balth examines the question of perception, a question that has a long tradition in Dutch art but that is asked anew in his work by means of contemporary materials, techniques, and ways of seeing — from Plexiglas light objects in the late 1960s to digital videos in his most recent work. Especially in the last two decades Balth has examined the intersections between painting, photography, and new media, and is thus part of a growing group of artists who put the question of interdisciplinarity central, venturing into fields of exploration that lie between the different art forms.Over the years Balth’s work has always had strong affinities with what was current in contemporary art. In his most recent series of Videowatercolors and digital videos he borrows in subtle ways motifs and imagery from the work of other contemporary artists — among others Zhang Wang, Olafur Eliasson, Cildo Meireles, Angela Bulloch, Liam Gillick — and hence plays on themes and questions that are topical. The exhibition aims to link the earliest work, which shows a marvelous play of light through Plexiglas wall objects, to a renewed interest today in the formal and perceptual dimensions of art — work that explores the interface between abstraction and concrete reality.

Background

Early on Balth received recognition with his Light Objects (1969-75), which were shown in the late 1960s and early 70s by gallerist Riekje Swart and in 1974 by Edy de Wilde in a small solo show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Two years later Rudy Fuchs and Jan Debbaut at the Van Abbemuseum made an exhibition with Balth’s Light-Photoworks (1976-78), which received a follow-up in a solo show in the Folkwang Museum in Essen, where he received another exhibition later, organized by Zdenek Felix. Balth participated in what is now recognized as the so-called “photographic turn in contemporary art,” to which Peter Weibel in his Vienna Secession of 1981 referred as “Erweiterte Fotografie” [Expanded Photography] and which included examples of Balth’s New Collage series (1979-82). Balth’s work increasingly began to develop in series, from the Polaroid Paintings (1982-86), Suites (1977-91) and Laser Paintings (1991-96), to the Vinyls (1997-99), Videowatercolors (2001— ) and digital videos (2011— ). Throughout the years this work received recognition both in the Netherlands —among others a solo show in the Groninger Museum curated by Frans Haks and in the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague made by Hans Locher— and abroad — taken up by Zdenek Felix in Essen, Rainer Crone in New York (the Wallach, Castelli and Sonnabend galleries), and more recently by Lyle Rexer in a traveling exhibition (since 2009) in the US (The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography). Most recently, I was able to stage –with generous support from the Mondriaan Foundation— Videowatercolors: Carel Balth Among His Contemporaries at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle (2011-12), offering with 44 works by Balth a broad overview of his oeuvre (selections from eight series) in relation to 18 works by contemporaries, among whom Warhol, Baldessari, Smithson, Richter, Sugimoto, Gursky, Tillmans, Lambri and Beshty.

Design

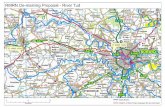

A possible presentation could be a preliminary selection of some twenty works, with the option of adding a few works from 2012 and 2013 in order to assure topicality. I plan to pick only a few works from five series, which together form a dynamic whole and create a balanced image of Balth’s place in the contemporary art world of the last forty years. The earliest work, in the form of Light Objects of which four were shown at this year’s TEFAF in Maastricht, is important because the play of light and space has gained interest in recent times — a fact that receives a new interpretation in Balth’s recent, luminous digital videos, such as Materialization II, which builds on the Videowatercolors but is also based on the colorful, atmospheric ambiance of a work by Olafur Eliasson. Working with light and shadow is central to the Light Objects, such as 1 Meter Light (1973), which by means of light and shadow lines on the wall actually separates two components that normally are inseparable. When Balth speaks of “sculpting with light on the canvas of reality,” he conjures up, already early on in his career, the image of an area that is situated between painting and sculpture (Balth began as a painter, in 1967). And by admitting color into some of the Light Objects, and by allowing it to radiate onto the wall by way of an indirect light falling through the Plexiglas, Balth suggests that light can be a medium that painting has to share with sculpture, that a one-sided attachment to the medium (Greenberg) belongs to the past. In four works from the Suite we see the result of the projection of a razor-sharp rectangle of bright light into the pitch-dark of the night, which sometimes yields ephemeral and capricious, sometimes solid, almost sculptural forms, forms which return in the first Laser Paintings. Two selected works from 1995 from this series carry the suggestive title A la recherche and play on both the poetic dimensions of time and memory in Proust’s masterpiece as well as the role played by technology in today’s re-valuation of painting. In the Videowatercolors, represented by a selection of seven works, we find two or more moments from a digital video recording printed on watercolor paper or canvas, whereby a connection is forged between the continuous, kaleidoscopic flow of pixels across the whole image and the fluid gestures that compose a watercolor. The title invokes the

Light Objects (1969-75)All Light Objects consist of crystal-clear Plexiglas and take light as their medium. Balth thus sought to concretize light as clearly as possible, and to allow light and matter to flow into each other, thereby involving the viewer in the process of separating the two. The first works in the series often have set into the Plexiglas shiny metal bands, which reflect the light in poetically suggestive ways. Later works, such as the rods (long, hanging bars, which are able to turn slowly), actively play with light because of the subtle movement in the refractions of the light. Some of the works also have color, which is not always directly visible as paint, but therefore precisely lends a sort of mysterious, radiant effect around the object. The largest group consists of often-simple rectangles that, by way of cuts into the material, project a light- and shadow line on the wall. They retain a remarkable luminosity, especially under lower light conditions, thereby apparently enhancing the light lines, which causes wonderment at such a simple given.

This page : Exhibition at Charles Kriwin Gallery, Brussels, 1973 (photo by Jan Versnel)Next page left : Untitled, 1971, 100 x 100 cm (photo by Jan Versnel)Next page right : Untitled, 1969, 70 x 70 cm (photo by Jan Versnel)

Previous pages left : Carel Balth in his studio with Light Objects, 1973 (photo by Jan Versnel)right : Corner Piece, the Perception of Color (Yellow), 1974, acrylic on plexiglas. 200 x 2,5 x 2,5 cm

This pageThree works from Suite II, 1977 - 1991, laser print on aluminum with epoxy finish.each 135 x 100 cm

Suite I and Suite II (1977-91)Balth arrived at these images by projecting a razor-sharp rectangle of white light into the darkness of night. The at times capricious, at times solid shapes that resulted represent an attempt to address reality by means of artificial light in a rather abstract manner, by concretizing, rather than simulating. In discussions of photography, from C. S. Pierce, via Roland Barthes and Rosalind Krauss, the question of indexicality has been key, an ontological question, which lends to photography a reality effect because the print is an (indexical) trace of light captured on the sensitive plate. Due to the laminate on these photos, rich contrasts have been well preserved — the night is truly black, attaining a sort of materiality that contrasts with the lighter parts, which sometimes appear sculptural, sometimes take the form of a hesitatingly searching line.

The New Collages (1979-82)Balth plays on the idea of reflection — the photograph reflecting earlier reality, while the collaged foil literally reflects light here and now. The viewer, in turn, reflects on the real-scale juxtaposition. Balth revived collage to include the medium of photography. He used commonplace motifs and emphasized materiality by maximizing contrasts and similarities: the light raking across the walls, the shadow cast by the foil, its curvature in real space, and the curves resulting from the cutting out of shapes. These elements reveal what is real and what is only represented, while putting the idea of collage itself into question.

Left : The New Collage (11), 1980/81, 61 x 45 cmRight : The New Collage (2), 1979/80, 101 x 136 cm

The New Collage (10), 1981, 101 x 136 cm

Left page : A la Recherche, 1995, Inkjet print on canvas, 116 x 85 cmRight page : A la Recherche, 1995, Inkjet print op canvas, 176 x 125 cm A la Recherche, 1995, Inkjet print op canvas, 176 x 125 cm

Laser Paintings (1991-96)The Laser Paintings derive their name from a process Balth developed in the mid 1980s. He scanned an image with a laser scanner, which he then manipulated and printed enlarged on canvas. Because the canvas ran untreated and unprimed through the large inkjet plotter, the pigments in this dot-shooting process were not sprayed onto but into the canvas, resulting in beautiful sfumato color effects. In the series which Balth in playful homage to Proust called A la recherche, we find images that are at first sight difficult to place, because the motif — the brushstroke of Monet from his Nymphéas series of waterlillies — was already blown up 2,500 times on the scanned photograph. Moreover, Balth had wrinkled the paper of the photograph, so that the image enhances the sense of something that flows. The references to Monet’s brushstroke, the capturing of the light of the moment, the sfumato of flowing color, and the disorienting effect which Leo Steinberg also noted in Monet’s Nymphéas all again conjure up an image of a water landscape of sorts. As I described in The Touch of Light: Laser Painings by Carel Balth (1993), the light of the laser scan becomes an index of a process of digital translation that, as with the nearly blind Monet, holds onto the reality of painting by only a hair.

Videowatercolors (2000 — )The name Videowatercolors conjures up the image of two mediums that are almost opposed yet nevertheless have the flow of the image in common. Because digital video has no stills but consists of a maelstrom of thousands of pixels that simultaneously transform the entire image field, the so-called Videograbs that Balth chooses and enlarges from a longer take are a kind of materialized metaphor of the flow of time and light across certain surfaces. In Moving IV, which at first sight has something sensual about it, a sort of blown-up image of lips, we actually see a red seat Balth videoed on a train, the light shifting with the movement of the train and time and the pliable skin of the seat conjuring up the presence of travelers. Moving II consists of four parts of which the bottom two are recognizably of undulating water; the top two, however, appear strange, as though we witness a sort of icy, stringy substance — until we tilt our head to the left or right and recognize that our sight is completely conditioned. Skyscape (Blue Horizon) looks like a landscape but in reality consists of two Videograbs from a long shot taken with the lens of the video camera held still against an airplane window. Dark clouds announce themselves in the top image and form, a little while later, a thick blanket below, so that in reality we are looking at different manifestations of water, including the ice crystals that have formed on the window, which engage in a kind of digital dance with the pixels of the flowing image that Balth presents.

Moving II, 2002, Inkjet print on canvas, 140 x 195 cm

Skyscape (Blue Horizon), 2003, Inkjet print on plexiglas, 108 x 141 cmRound Trip II, 2012, Inkjet print on canvas, 160 x 140 cm

Dawn, 2008, Inkjet print on canvas, 190 x 140 cm Transvision V, 2011, Inkjet print on canvas, 140 x 160 cm

Installation Henry Art Gallery , Seattle , oktobre 2011 - january 2012Left page : Time Shift IV, 2009-2010, Inkjet print on canvas, 140 x 145 cm

Left : Materialization I, 2011, digital video, 4min 59sec loopRight : Materialization II, 2011, digital video, 5min 12sec loop

Digital Videos (Materializations) (2011— )The two selected works from the recent new series of digital videos derive from the Videowatercolors, a kind of moving version, projected on what appears to be a floating screen or board set slightly off the wall. The slowly moving images had an enchanting effect on the audience that first saw these works in public in the fall of 2011 and beginning of 2012 at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle. Materialization I, shown in the brochure as a combination of stills, is fragmented in a manner typical of Balth; the viewer experiences shifts in the imagery as shifts in time and space through subtle manipulations of light and color.

Marek Wieczorek

Marek Wieczorek is a Dutch curator and Associate Professor of modern and contemporary art history at the University of Washington in Seattle. He specializes in modern and contemporary art, in particular the question of the avant-garde and abstraction. He has published among others on De Stijl, Mondrian, Georges Vantongerloo, Gerhard Richter, Carel Balth, the Situationist International, and “bioart.” He has curated exhibitions in Europe and the US and has collaborated on the traveling retrospective of Vantongerloo and contemporaries and the exhibition of De Stijl that was recently shown at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou. His first show, The Desire of the Museum (Whitney Museum of American Art, 1989), is now known as one of the first exhibitions with art that critically examines the museum as institution. His most recent exhibition was Videowatercolors: Carel Balth Among His Contemporaries (Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, Oct. 2011- Jan. 2012).

Carel Balth

Making sculptures with light on the canvas of reality. 1978

The question is how to formulate the complexity of our time without losing hope for the future. 2000

There is new territory to explore - a more abstract way of looking at reality. 2011