Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

-

Upload

bocahbritpop -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

-

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

1/9

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-3794; originally published online November 30, 2009;2010;125;60Pediatrics

Shouldice, Hosanna Au and Kathy Boutis

Nisanthini Ravichandiran, Suzanne Schuh, Marta Bejuk, Nesrin Al-Harthy, MichelleDelayed Identification of Pediatric Abuse-Related Fractures

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmllocated on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2010 by the American Academypublished, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

2/9

Delayed Identification of Pediatric Abuse-RelatedFractures

WHATS KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Patient assessment byphysicians of children who are at risk for abuse is suboptimal,

and, therefore, abusive fractures are at risk for escaping

detection or delayed recognition. It is unknown, however, how

often this occurs.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: Approximately 20% of abusive

fractures were missed at initial physician visits. Boys who

present to a nonpediatric ED with an extremity fracture seem to

be at highest risk of the abusive etiology of the fracture escaping

of detection by a physician.

abstractOBJECTIVES: Because physicians may have difficulty distinguishing

accidental fractures from those that are caused by abuse, abusive

fracturesmay be at risk fordelayed recognition;therefore, the primary

objective of this study was to determine how frequently abusive frac-

tures were missed by physicians during previous examinations. A sec-

ondary objective was to determine clinical predictors that are associ-

ated with unrecognized abuse.

METHODS:Children who were younger than 3 years and presented toa large academic childrens hospital from January 1993 to December

2007 and received a diagnosis of abusive fractures by a multidisci-

plinary child protective team were included in this retrospective re-

view. The main outcome measures included the proportion of children

who had abusive fractures and had at least 1 previous physician visit

with diagnosis of abuse not identified and predictors that were inde-

pendently associated with missed abuse.

RESULTS:Of 258 patients with abusive fractures, 54 (20.9%) had at

least 1 previous physicianvisit at which abuse was missed. The median

time to correct diagnosis from the first visit was 8 days (minimum: 1;

maximum: 160). Independent predictors of missed abuse were malegender, extremity versus axially located fracture, and presentation to a

primary care setting versus pediatric emergency department or to a

general versus pediatric emergency department.

CONCLUSIONS: One fifth of children with abuse-related fractures are

missed during the initial medical visit. In particular, boys who present

to a primary care or a general emergency department setting with an

extremity fracture are at a particularly high risk for delayed diagnosis.

Pediatrics2010;125:6066

AUTHORS:Nisanthini Ravichandiran,

a

Suzanne Schuh,MD,a Marta Bejuk, MD,a Nesrin Al-Harthy, MD,a

Michelle Shouldice, MD,b Hosanna Au, MD,b and

Kathy Boutis, MD, MSca

Divisions ofaPediatric Emergency Medicine andbPediatric

Medicine and Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect, Hospital for

Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

KEY WORDS

pediatrics, child abuse, bone fractures, diagnosis

ABBREVIATIONS

EDemergency department

SCANSuspected Child Abuse and Neglect

HSCHospital for Sick Children

ORodds ratio

CIconfidence interval

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2008-3794

doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3794

Accepted for publication Jul 28, 2009

Address correspondence to Kathy Boutis, MD, MSc, 555

University Ave, Toronto, ON, M5G 1X8, Canada. E-mail:

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have

no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

60 RAVICHANDIRAN et alat Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

3/9

Although fractures are a common pre-

senting finding in child abuse,1,2 clini-

cians may have difficulty differentiat-

ing abuse-related fractures from

those that are caused by accidental

trauma24; however, this distinction is

crucial because of its impact on con-sequences for the child.5,6 Whereas

accidental injuries carry only their

inherent risks, repeat injury occurs

in 35% of all abuse cases, and 5% to

10% of patients will die if there is no

intervention.7

Despite the serious risks associated

with delayed recognition of abusive

fractures, patient assessment for this

diagnosis is often suboptimal.14,8 One

study found that of 100 children who

were younger than 3 years and pre-

sented to an emergency department

(ED) with long bone fractures, 31 had

indicators suggestive of abuse but only

1 was referred to child protection ser-

vices for additional assessment.2 Ban-

askiewitz et al3 demonstrated that in

infants who were younger than 1 year,

the possibility of abuse was underesti-

mated by ED clinicians in 28% of

cases when compared with a retro-

spective diagnosis by a child protec-

tion team pediatrician. Moreover, re-

search conducted in a pediatric ED

demonstrated that 42% of charts re-

viewed did not have adequate docu-

mentation to explain the cause of the

fractures, and inflicted injuries were

therefore not adequately ruled out.1

This evidence suggests that abusive

fractures arelikely at risk for escapingdetection or delayed recognition; how-

ever, the frequency with which this oc-

curs remains unknown. The primary

objective of this study was to deter-

mine the proportion of abuse-related

fractures that were missed at previ-

ous physician encounters. The clinical

factors that may have contributed to

the reasons for the diagnostic delay

were also examined.

METHODS

Patient Population

Children who were younger than 3

years,2,911 had abusive fractures that

occurred from January 1993 to Decem-

ber 2007, and were referred to amultidisciplinary hospital-based Sus-

pected Child Abuse and Neglect (SCAN)

team at the Toronto Hospital for Sick

Children (HSC) were included. HSC

SCAN consists of specialty pediatri-

cians, psychologists, social workers,

and nurse practitioners. Members of

HSC SCAN team are the only child

abuse specialists in the Greater To-

ronto Area and are involved in the as-

sessment of most cases of suspected

abuse in that area. The HSC SCAN

teams assessment results in a classi-

fication of these fractures as abusive,

indeterminate, or accidental. The study

sample included only cases for which

the first physician visit was primarily

for an isolated fracture. Cases were

excluded when the childs clinical pre-

sentation was predominantly consis-

tent with some other type of trauma,

medical records were inaccessible,

only metaphyseal corner chip frac-

tures (usually asymptomatic) were

present, or the cause of the fracture

was indeterminate or accidental.

Definitions

Fractures were determined to be abu-

sive when at least 1 of the following

criteria was met2,6,12: (1) confession of

intentional injury by an adult caregiver;

(2) inconsistent/inadequate history

provided; (3) inappropriate delay in

seeking medical care; (4) associated

inadequately explained injuries; (5)

in the absence of bone disease, pres-

ence of fractures uncommon for

accidental injury and frequently re-

ported in abusive injury (eg, meta-

physeal limb fractures, posterior rib

fractures not caused by birth trau-

ma)6,13,14; and (6) witness to abuse

came forward.

A case was considered recognized

when a referral to local child protec-

tion authorities was made the first

time the child presented to a physician

with the index fracture(s). This is in

contrast to missed when the child

had at least 1 physician encounter forthe index fracture(s) before the visit

when the abuse was confirmed. In all

missed cases, the signs andsymptoms

compatible with a fracture and/or a

radiograph diagnosis were present at

the initial visit, but the possibility of

abuse was not raised. Thereafter, 1

of the following occurred: (1) the child

improved clinically but experienced re-

peat trauma and the HSC SCAN team

found the previous fracture(s) abu-

sive; (2) recognition of red flags and

referral to the SCAN team at a routine

follow-up for the index fracture(s) led

to recognition of abuse; (3) the childs

continued symptoms resulted in re-

peat unscheduled visits and a referral

to the SCAN team with recognition of

the index fracture(s) as abuse-related;

(4) the index radiographs initially read

as normal by the primary treating phy-

sician were found by a radiologist to

have a fracture that required a repeat

visit, when the suspicion for abuse was

raised; (5) the perpetrator later con-

fessed or a witness came forward;

and/or (6) abuse was suspected in a

sibling and review of the patients frac-

tures yielded abuse as the cause. The

determination of missed versus recog-

nized cases was made independent of

the knowledge of potential predictors.Because specific income of the fam-

ily was not available, this was esti-

mated on the basis of median income

of families in a given postal code.15

On the basis of the 2006 Ontario me-

dian household income of $60 455,

median income was then additionally

classified as low ($45 341.25), mid-

dle ($45 341.25$90 682.50), or high

($90 682.50).16 Income classifica-

ARTICLES

PEDIATRICS Volume 125, Number 1, January2010 61at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

4/9

tion was used as a surrogate mea-

sure of socioeconomic status.17

Social concerns were defined as any

primary caregiver who had 1 of

the following: young single parent

(younger than 20 years and no live-in

partner at the time of the childs eval-

uation); previous contact with child

protection services; or history of incar-

ceration, substance abuse problem,

living in group housing (eg, shelter), or

domestic violence. A positive skeletal

survey was defined as additional frac-

tures other than the index fracture(s).

In a primary care office, children are

assessed by a family physician or

pediatrician. In general EDs that

serve all ages, children are seen by

ED physicians.

Case Selection, Data Collection,

and Review

Once the HSC SCAN team has reviewed

a case, referral information is entered

into a database. This database was

searched for eligible patients, and

study-specific information of identified

cases was collected from original pa-

tient records (Fig 1). Information col-

lected by 2 research assistants (Ms

Ravichandiran andDr Bejuk) whowere

trained in the methods of chart ab-

straction included relevant patient

and family demographics, social his-

tory, history of present illness, details

of the childs injury(ies), subsequent

clinical course, and details from previ-

ous visits related to the index frac-

ture(s). For missed cases, the clinical

data from the initial physician visit(s)

before the visit when abuse was diag-nosed were reviewed by 1 SCAN physi-

cian (Dr Al-Harthy), who was masked

to the final SCAN opinion and the pur-

pose of the study, to ascertain the

presence of indicators of abuse that

should have led to a referral to a child

protective team at that visit.

An a priori defined list of potential pre-

dictors that were independent of the

outcome of a missed diagnosis of

abuse was selected by 3 expert mem-

bers of the HSC SCAN team1,2,6,10,12,18,19

and later modified in accordance with

the available data. For example, al-

though race3,8,12 has been strongly as-

sociated with referrals to child protec-

tive teams, this information is notcollected by the reviewing HSC SCAN

team. The final list of predictors is de-

tailed in Table 1. Some of the variables

used routinely in ascertaining abuse

could not be considered as predictors

because they are not independent of

the outcome.

After data collection was complete, in-

formation on each patient was re-

viewed for accuracy and completeness

by a pediatric ED physician (Dr Boutis)in collaboration with the 2 research

assistants. Missing data were imputed

by inserting the respective median

(categorical) or mean (continuous

data) value from the group data into

blank cells.20 Permission for this re-

search was obtained from our re-

search ethics board.

Analysis

The sample size was calculated by us-ing the methods by Hsieh21 and the fol-

lowing parameters were used:

.05, and .20, estimated proportion

of missed abusive fractures of 20%,22

and an odds ratio (OR) of 2.023 of

missed abuse corresponding to an in-

creaseof1SDfromthemeanvalueofa

covariate.21 In this study, there are

multiple covariates and a possibility of

some unknown correlation between

covariates. Thus, a conservative valueof .5 was estimated, and the ad-

justed minimal total sample size is

therefore 182.

A univariate analysis was used to as-

sess whether a particular variable

was associated with the outcome vari-

able of interest, missed case of abu-

sive fracture (Table 1). For the latter,

Pearson2 test was used for categor-

ical values and independent Students

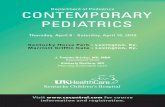

FIGURE 1Patient inclusion/exclusion flow diagram.

62 RAVICHANDIRAN et alat Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

5/9

ttest for continuous variables. Inde-

pendent variables with P .20 and any

relevant interaction and confounding

terms were entered into a multivariate

logistic regression model using the

forward selection method (Table 2).24

Approximately 14 missed cases per

variable were entered into the model,

meeting the minimal criteria of 10

events per variable to minimize over-

fitting of the data.2527 Wald and Like-

lihood ratio testing were then used

to iteratively remove noncontributory

variables from the model.24 Goodness

of fit of the final model to the data was

tested by using the Hosmer-Lemeshow

test. A receiver operating characteris-

tic curve was plotted to check the pre-

dictive ability of the model. Odds of a

case being missed for a given variable

were reported with respective 95%

confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses

were performed by using SPSS 13 for

Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

This study included 258 eligible pa-

tients with abusive fractures (Fig 1).

A comparison of characteristics of

missed and recognized cases is de-

tailed in Tables 1 and 2. Of the 258 pa-

tients, 54 (20.9% [95% CI: 15.8 26.0])

had at least 1 previous physician visit

at which abuse was missed. Of the 145

children with an abusive extremity

fracture, 41 (28.3% [95% CI 20.8 35.8])

were missed. From the initial visit for

the index fracture(s), the median delay

of the diagnosis of abuse was 8 days

(minimum: 1; maximum: 160), and the

median number of physician visits was

1 (minimum: 1; maximum: 3). Of the

children who re-presented for medical

care after the abusive cause of the

fracture was missed, 9 (16.7%) pre-

sented with new abusive injuries. In 7

of these cases, there was a different

fracture; 1 child had serious abdomi-nal injuries, and another had serious

head trauma that resulted in death.

Incorrect interpretation of the radio-

graph findings by the physician re-

sulted in 18 (33.3%) missed cases

(Fig 2), 7 of which were skull fractures.

In 7 (13.0%), the initial imaging series

was incomplete and the abuse-related

fracture was therefore not seen. This

subgroupreturnedto an ED because of

persistence of symptoms, more exten-sive imaging was performed, the frac-

ture was detected, and a referral to

the SCAN team was made. The exact

reasons that the remaining 29 cases

were missed are not certain because

of a lack of available data; however,

inadequate screening or accepting im-

plausible mechanisms may have con-

tributed to missing these cases. SCAN

documentation revealed that these

children had risk factors for abuse: 25(86.2%) of 29 were nonambulatory; in

26 (90.0%) of 29, parental report of

mechanism did not explain injuries;

and 14 (48.3%) of 29 had social con-

cerns. Furthermore, review of the ini-

tial visit records demonstrated that 13

(50.0%) of 26 had incomplete docu-

mentation of the preceding events or

possible related risk factors for abuse.

The univariate analysis demonstrated

that 3 variables were found to be sig-nificantly associated with a missed di-

agnosis of abuse: male gender, initial

presentation to a nonpediatric ED, and

an extremity fracture (Table 1). The

probability of missing this diagnosis

for each predictor after adjustment

for all significant predictors is summa-

rized in Table 3. No statistically signifi-

cant interaction terms or confounding

variables were identified in this analy-

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Missed and Recognized Abuse Cases

Characteristic Recognized

Cases

(n 204)

Missed

Cases

(n 54)

Pfor Univariate

Analysis of

Independent

Variables

Potential predictors independently associated with

missed abuse

Age, mean

SD, mo 8.28

7.05 9.24

8.31 .3910Male gender, % 44.4 60.8 .0250a

Pediatric ED setting at initial visit, % 89.9 10.1 .0001a

Injury event reported, % 41.5 38.9 .8840

Extremity fracture, % 51.0 75.9 .0010a

Parents living apart, % 26.5 31.5 .4410

Low socioeconomic status, % 27.4 22.4 .6100

Additional baseline characteristics (not independently

associated with missed abuse)

Nonambulatory, % 71.6 66.7

No. of fractures on initial radiograph, median (range) 1 (2) 1.0 (2)

Positive skeletal survey,n(%) 82 (40.1) 34 (63.0)

No. of fractures on skeletal survey, median (range) 1 (25) 2 (26)

Lack of plausible mechanism, % 98.5 94.4

Delay in seeking care, % 29.5 38.9

Single caregiver, % 26.0 29.8Social concerns, % 43.6 50.9

a Statistically significant.

TABLE 2 Fracture Locations of Recognized

Versus Missed Cases

Fracture

Location

Recognized

Abuse

Cases

(n 204)

Missed

Abuse

Cases

(n 54)

Clavicle,n(%) 8 (3.92) 2 (3.70)

Humerus,n(%) 32 (15.70) 13 (24.10)

Forearm,n(%) 19 (9.30) 7 (13.00)

Wrist,n(%) 0 (0.00) 1 (1.90)

Digits,n(%) 0 (0.00) 1 (1.90)

Femur,n(%) 48 (23.50) 9 (16.70)

Tibia/fibula,n(%) 24 (11.80) 11 (20.40)

Scapula,n(%) 0 (0.00) 2 (3.70)

Skull,n(%) 73 (35.80) 15 (27.80)

Sternum,n(%) 4 (2.00) 0 (0.00)

Totala 208 61

a Numbers exceed total number of patients because some

patients had1 fracture.

ARTICLES

PEDIATRICS Volume 125, Number 1, January2010 63at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

6/9

sis. In the resultant model, the Hosmer-

Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test did not

reject the null hypothesis of good fit

(P .718), and the predictive ability of

the model is good (area under the

curve: 0.841). Applying this model pre-

dicts that if all 3 factors were present,then the probability that an abusive

fracture would be missed is 50%.

Sixteen charts were missing and un-

available for review, and if we assume

that all were recognized abuse, then

the proportion of missed abuse would

decrease only to 54 (19.1%) of 274. Of

the 139 initial visits that occurred out-

side HSC, 3 of 45 of the missed and 15

of 94 of the recognized first physician

visit documents were not available for

detailed review. In 2 (0.8%) of the 258

cases, the initial clinical setting could

not be determined. In 16 (6.2%) cases,

it was uncertain whether an injury was

reported. Forty (15.5%) had living sta-

tus of parents unavailable. Finally, a

postal code was not recorded for 49

(19.0%) cases. Sensitivity analyses

with and without imputed data for

these missing variables were per-

formed and did not reveal any signifi-

cant differences; therefore, only unim-

puted results are presented.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to report the fre-

quency of delayed recognition of abu-

sive fractures in children. One fifth of

children with abusive fractures were

missed at initial physician visits, which

is comparable to that reported for

other types of abuse12,19; however, we

do not know how many cases of abu-

sive fractures are never detected. We

also found that boys, children who

present to a nonpediatric ED or a pri-

mary care setting, and/or those with

an extremity fracture seem to be at the

highest risk of the abusive etiology of

the fracture escaping of detection by a

physician at an initial visit.

In 17% of missed abuse cases, chil-

dren sustained repeat injuries be-tween their initial visit and their even-

tual diagnosis of abuse; previously

missed fractures that led to serious

abusive injuries were also found by

Oral et al.28 The skeletal survey that

was performed during subsequent vis-

its may have a major impact on the

correct diagnosis. In this study, two

thirds of patients had healing frac-

tures identified on the survey, and this

is higher than that reported previous-ly.5,22 This highlights the importance of

having a low threshold to consider a

skeletal survey for children who may

be at risk for abuse5,14,22 before dis-

missing the fractures as accidental.

In the 54 missed cases, approximately

one third of the fractures were not

detected on the initial radiographs

by front-line physicians in a country

where immediate radiology interpre-

FIGURE 2A, Missed versus recognized abusive fracture cases. B, Recognized versus missed abusive fracture cases by presentation site.

TABLE 3 Predictor Variables That Were

Independently Associated WithMissed Abuse

Predictor OR 95% CI

Male vs female gender 2.00 1.033.80

Setting

Primary care office vs

pediatric ED

5.20 1.7715.39

General ED vs pediatric ED 7.20 3.0017.30

Extremity vs axial skeleton

fracture

2.30 1.104.77

64 RAVICHANDIRAN et alat Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

7/9

tations are not routine practice in the

ED or office setting. Pediatricians have

limited skills in the recognition of frac-

tures on radiographs.29 This is true

particularly of skull fractures,30 and

identification of this type of fracture,

especially in very young infants, mayprompt the physician to assess for

other maltreatment risk factors.31 This

study suggests that front-line physi-

cians should strongly consider con-

sulting a radiologist when the pres-

ence of a fracture may lead to

increased suspicion of abuse.

In our study, abuse was more likely to

be missed when a child presented to a

general ED or primary care setting.

These results support those by Trokelet al,23 who found lower rates of abuse

in patients who had traumatic brain

injury or femur fracture and pre-

sented to general hospitals compared

with their pediatric counterparts. This

could suggest that abuse may be

missed in these settings. Clinicians

who work in these areas may lack ex-

pertise in the recognition of abuse-

related fractures despite the presence

of indicators for abuse.1,2,32

This re-search supports the need for quality

improvement programs at general

hospitals and primary care settings.

Children with extremity shaft frac-

tures caused by abuse were also found

to be at increased risk for having

physicians attribute their injuries to

accidental causes. Although extremity

fractures are the most common skele-

tal injuries that occur in abused chil-

dren,2

radiology literature demon-strates that these injuries also have

the lowest specificity for abuse.14 No

fracture on its own can distinguish an

accidental from a nonaccidental trau-

ma,31 but the likelihood of abuse in-

creases when there is a fracture in a

nonambulatory child and when the

fracture type includes the femur or hu-

merus in infants who are younger than

18 months.31,33,34 Indeed, in this study,

these types of fractures in nonambula-

tory children were commonly seen in

cases for which abuse was missed. Inaddition, many of the missed extremity

fractures had associated risk factors

for abuse that were not adequately

screened for at the initial physician

visit; therefore, the possibility of abuse

should be carefully considered for

children with extremity fractures, and

associated risk factors should be

excluded.

An abuse-related fracture was almost

twice as likely to be missed in a boyversus a girl. Although the reason for

this is unclear, injuries in general oc-

cur more often in boys,35 which may

bias a clinician in assuming that the

cause of a fracture is accidental.

This study has limitations that warrant

consideration. This was a retrospec-

tive study with its inherent limitations,

such as missing data, and thus absent

data may have biased predictor vari-

able results. Although our case classi-fication was based on current avail-

able standards for the diagnosis of

abuse, there may have been ascertain-

ment errors. Children with abusive

fractures that were never referred to

the SCAN team and were assumed to

be accidental were not included in this

review; however, given that ED records

are often incomplete,1 a retrospective

assessment by the child protection

team of all of the nonreferred caseswould have resulted in only specula-

tive assignments of cause. Finally, al-

though most cases of abusive frac-

tures are seen by our SCAN team, some

of the less complex cases may not have

been seen. This introduces the poten-

tial for referral bias, and it may result

in an overestimation of the proportion

of cases that are missed at an initial

physician visit; however, child abuse is

underrecognized,12 and there is also

the possibility that we are underesti-

mating the proportion of casesmissed.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that a consider-

able proportion of abuse-related pedi-

atric fractures are missed during the

initial visit. We can make the following

suggestions that may facilitate the di-

agnoses of abusive fractures. A de-

tailed review of the mechanism and

screening for other risk factors ofabuse should be included in the initial

assessment of a young child with frac-

tures. Children who are nonambula-

tory are at especially high risk, and

consultation with the child protection

team in these cases is often appropri-

ate. Clinicians should have a low

threshold to perform a skeletal survey

in potentially vulnerable populations,

and a radiologists review of any imag-

ing that may change suspicion forabuse is recommended. Finally, appro-

priate targeted education or practice

guidelines may help in achieving bet-

ter outcomes in clinical settings that

are susceptible to missing abusive

fractures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a

grant from the Canadian Hospitals In-

jury Reporting and Prevention Pro-

gram (CHIRPP).

We acknowledge the efforts of Dr S.

Walter and Mr A. O. Odueyungbo for

statistical expertise and critical review

of the analysis.

ARTICLES

PEDIATRICS Volume 125, Number 1, January2010 65at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

8/9

REFERENCES

1. Oral R, Blum KL, Johnson C. Fractures in

young children: are physicians in emer-

gency departments and orthopedic clinics

adequately screening for possible abuse?

Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(3):148153

2. Taitz J, Moran K, OMeara M. Long bone frac-

tures in children under 3 years of age: is

abuse being missed in emergency depart-

ment presentations? J Paediatr Child

Health. 2004;40(4):170174

3. Banaszkiewicz PA, Scotland TR, Myerscough

EJ.Fractures in children younger than age1

year:importanceof collaboration withchild

protection services.J Pediatr Orthop.2002;

22(6):740744

4. Lane WG, Dubowitz H. What factors affect

the identi fication and reporti ng of child

abuse-related fractures? Clin Orthop Relat

Res.2007;461:219225

5. Leventhal JM. The field of child maltreat-ment enters its fifth decade. Child Abuse

Negl.2003;27(1):1 4

6. Leventhal JM, Thomas SA, Rosenfield NS,

Markowitz RI. Fractures in young children:

distinguishing child abuse from uninten-

tional injuries. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147(1):

8792

7. Johnson CF, Oral R.Diagnosis and Manage-

ment of Child Abuse of Children. Columbus,

OH: Ohio State University Print Shop; 1999

8. Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian

CW. Racial differences in the evaluation of

pediatric fractures of physical abuse.JAMA.2002;288(13):16031609

9. Akbarnia B, Torg JS, Kirkpatrick J. Manifes-

tation s of the battered child syndrome.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(6):1159

1166

10. Fong CM, Cheung HM, Lau PY. Fractures as-

sociated with non-accidental injury: an or-

thopaedic perspective in a local regional

hospital. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11(6):

445451

11. Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of

fractures in accidental and non-accidental

injuries in children: a comparative study.Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6539):

100102

12. Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay

TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive

head trauma [published correction ap-

pears inJAMA.1999;282(1):29].JAMA.1999;

281(7):621626

13. Kleinman PK. Diagnostic Imaging of Child

Abuse. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998

14. Kleinman PK, Marks SC Jr, Richmond JM,Blackbourne BD. Inflicted skeletal injury: a

postmortem radiologic-histopathologic

study in 31 infants. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

1995;165(3):647 650

15. Statistics Canada. Census Tract Profiles,

2006 Census. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 2006.

Available at: www12.statcan.ca/english/

census06/data/profiles/ct/Index.cfm?

LangE. Accessed August 8, 2008

16. Statistics Canada. Study: Income Inequal-

ity and Redistribution. Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada; 2007. Available at: www.statcan.

gc.ca/daily-quotidien/070511/dq070511b-

eng.htm. Accessed September 12, 2008

17. Heisz A. Income inequality and redistribution;

1976 to 2004. Analytical Studies Branch Re-

search Paper Series.2007;(298):158

18. dos Santos LM, Stewart G, Meert K, Rosen-

berg NM. Soft tissue swelling with fractures:

abuse versus nonintentional. Pediatr Emerg

Care.1995;11(4):215216

19. King WK, Kiesel EL, Simon HK. Child abuse

fatalities: are we missing opportunities for

intervention. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;

22(4):211214

20. Fung KY, Wrobel BA. The treatment of miss-

ing values in logistic regression. Biometri-cal Journal.2007;31(1):35 47

21. Hsieh FY. Sample size tables for logistic re-

gression.Stat Med. 1989;8(7):795802

22. Dalton HJ, Slovis T, Helfer RE, Comstock J,

Scheurer S, Riolo S. Undiagnosed abuse in

children younger than 3 years with femoral

fracture.Am J Dis Child.1990;144:875878

23. Trokel M, Wadimmba A, Griffith J, Sege R.

Variation in the diagnosis of child abuse in

severely injured infants [pubished correc-

tion appear s in Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):

1324].Pediatrics.2006;117(3):722728

24. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE, NizamA. Applied Regression Analysis and Other

Multivariable Methods. 3rd ed. Pacific

Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company;

1998

25. Bagley SC, White H, Golomb BA. Logistic re-

gression in the medical literature: stan-

dards foruse andreporting,with particular

attention to one medical domain.J Clin Epi-

demiol. 2001;54(10):979985

26. Concato J, Feinstein AR, Holford TR. The risk

of determining risk with multivariable mod-

els.Ann Intern Med.1993;118(3):201210

27. Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR,

Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the num-

ber of events pervariable in logistic regres-

sion analysis.J Clin Epidemiol.1996;49(12):

13731379

28. Oral R, Yagmur F, Nashelsky M, Turkmen M,

Kirby P. Fatal abusive head trauma cases:

consequence of medical staff missing

milder forms of physical abuse. Pediatr

Emerg Care.2008;24(12):816 821

29. Ryan LM, DePiero AD, Sadow KB, et al. Rec-ognition and management of pediatric frac-

tures by pediatr ic resid ents. Pediatrics.

2004;114(6):15301533

30. Chung S, Schamban N, Wypij D, Cleveland R,

Schutzman SA. Skull radiograph interpreta-

tion of children younger than two years:

how good are pediatric emergency physi-

cians?Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(6):718722

31. Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Pat-

terns of skeletal fractures in child abuse:

systematic review.BMJ.2008;337:a1518

32. Ziegler DS,Sammut J, Piper AC.Assessment

and follow-up of suspected child abuse inpreschool children with fractures seen in a

general hospital emergency department.

J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41(56):

251255

33. Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Asnes AG. Inci-

dence of fractures attributable to abuse in

young hospitalized children: results from

analysis of a United States database. Pedi-

atrics.2008;122(3):599 604

34. Loder RT, Feinberg JR. Orthopaedic injuries

in children with nonaccidental trauma: de-

mographics and incidence from the 2000

kids inpatient database. J Pediatr Orthop.

2007;27(4):421426

35. Cramer KE, Scherl SA. Orthopedic Surgery

Essentials: Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: Lip-

pincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003

66 RAVICHANDIRAN et alat Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ -

8/10/2019 Pediatrics 2010 Ravichandiran 60 6

9/9

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-3794

; originally published online November 30, 2009;2010;125;60PediatricsShouldice, Hosanna Au and Kathy Boutis

Nisanthini Ravichandiran, Suzanne Schuh, Marta Bejuk, Nesrin Al-Harthy, MichelleDelayed Identification of Pediatric Abuse-Related Fractures

ServicesUpdated Information &

lhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmincluding high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

l#ref-list-1http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmat:This article cites 28 articles, 5 of which can be accessed free

Citations

l#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmThis article has been cited by 14 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

e_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abusChild Abuse and Neglectthe following collection(s):This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

Permissions & Licensing

mlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhttables) or in its entirety can be found online at:Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

Reprintshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2010 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Alland trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elkpublication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on June 22, 2014pediatrics.aappublications.orgDownloaded from

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#ref-list-1http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#ref-list-1http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#ref-list-1http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/child_abuse_neglect_subhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#related-urlshttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#ref-list-1http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html#ref-list-1http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.htmlhttp://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/125/1/60.full.html