PARTICIPATION EDUCATION COMMUNITY ...mcohen02.tripod.com/aplaceatthetable.pdfTales of the Hasidim)....

Transcript of PARTICIPATION EDUCATION COMMUNITY ...mcohen02.tripod.com/aplaceatthetable.pdfTales of the Hasidim)....

SPRING 2004– NISAN 5764 • VOLUME V, ISSUE 1

tion found expression in song. One ofthose is Shirat HaYam, the Song at theSea. There are two versions of this song.First Moses and the children of Israel singand then:

;,v ,t irvt ,ujt vthcbv ohrn je,uohp,c vhrjt ohabv kf itm,u vshchf 'vk urha ohrn ovk ig,u /,kjncu

/ohc vnr ucfru xux vtd vtd

Miriam the prophetess, the sister ofAaron, took the tambourine in herhand; and all the women followed herwith tambourines and dances. AndMiriam called to them: “Sing to God,the most exalted; horse and rider Godcast in the sea…(Exodus 15:20-21)

I read the following based on the teach-ings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe:

The men sang, and then the women. Themen sang…they sang their joy over theirdeliverance, they sang their yearning for amore perfect redemption—but somethingwas lacking. Something that only a woman’ssong could complete. Miriam and her chorusbrought to the Song at the Sea the intensityof feeling and a depth of faith unique towomankind.

The Midrash, quoted above, goes on tosay that the tenth song will be the shirhadash, the “New Song” of the ultimateredemption—a time when suffering, ignorance, jealousy and hate will vanishfrom the earth. So much of our liturgy is filled with references to this “NewSong.” Everyday in our morning prayerswe recite the words of the Psalmist: “Shirulo shir hadash”—Sing to God a new song. At our seder we sing again:

/vasj vrha uhbpk rntbuLet us sing before God a new song.

As we sit around our seder table thisyear, may we all be privileged to sing theold songs that are part of our heritage. Atthe same time, let us not be afraid to openourselves to the new—the shira hadasha.

A Happy and Kosher Pesach!

Iam an endangered species—I stillmake Pesach at home. While not near-ly as grueling as it once was, it is still

a lot of work. I often get caught up withthe cleaning, shopping and cooking andforget to take time for the studying.My friend Alice, who is not obser-vant, recently started makingseder. As she studied the Hagad-dah, she would periodically callme with the most wonderful ques-tions, and, for just a moment, Iwould sit and remember what the holiday is all about.

It is hard to find the “new” in some-thing you have been participating in forover fifty years. I love the old traditionspassed on to me by my parents. I want tokeep them for the next generation. How-ever, I also want my granddaughters tofeel part of the extraordinary story of theExodus from Egypt. The women were,after all, also part of the miracle. It wasYocheved, Moses’ mother, who had thefaith to bring a child into the world. It wasthe midwives, Shifrah and Pu’ah, who hadthe courage to deliver the children of theIsraelites. And it was Miriam, with herunrelenting optimism, who watched overher brother’s basket as he traveled downthe Nile.

I love setting the table before the seder,with its traditions old and new. One of thenew items on my table is Miriam’s Cup.As I fill this cup with water, I am remind-ed of the well that accompanied theIsraelites through the desert. This well, weare told, was given by God to Miriam tohonor her. Miriam’s Cup, the new symbolon my table, allows me to begin a conver-sation about the women who have beenan essential part of the story of the Exodusand of the Jewish people.

The Midrash tells us that there are tenoccasions when the experience of redemp-

From Our PresidentSing a New SongBy Carol Kaufman Newman

EDUCATIONPARTICIPATION COMMUNITY

WWW.JOFA.ORG

LEADERSHIPJournal

The issues of this year’s JOFA Journal are made possible through the generosity of Zelda R. Stern and The Harry Stern Family Foundation.

...continued on page 9

C lose to a thousand women and menattended JOFA’s Fifth InternationalConference on Feminism & Ortho-

doxy in New York, entitled “ZacharU’Nequevah Bara Otam (Male andFemale God Created Them): Women andMen in Partnership.” Twenty per cent ofthe attendees at the conference were men,and there were representatives from allover the United States, Israel, England,Canada, and Spain. Partnership was thetheme of the day, as participants consid-ered the ways in which women and menare partners in Jewish practice, learning,growth and change. As in the past, sessions explored increasing ritual oppor-tunities for women and examinedhalakhot that relate directly to women.However, this conference also addressedbroader social questions, examining thelarger implications of changing genderroles in Jewish families, institutions, synagogues and schools.

Dr. Tamar Ross’s opening plenarytouched on these issues by examining theconsequences of redefining gender roles.Rabbi David Silber, Rabbanit Malke Binaand Rabbi Dov Linzer participated in aforum moderated by Giti Bendheim aboutthe future of Jewish leadership. The ses-sion confronted new ideas and toughissues. The likelihood of one day havingwomen as Orthodox rabbis was discussedand viewed by many as an inevitable andpositive development.

Many of the conference’s smaller work-

Fifth International Conference on Feminism & Orthodoxy

Chavruta study and text sessions.

2

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

assover, a time of liberation,has also been a difficult time for women as we strug-

gle to rid our houses of every last bitof hametz. While today our house-hold responsibilities are increasinglyshared by women and men alike, ourJewish foremothers alone took on the task of preparing their homes forthe holiday. Some viewed this as alabor of love, a means of experiencingthe Exodus, while others felt the burden of preparation detracted from the spiritual experience of theseder. Today, as we clean our houses,we remember generations of womenbefore us who toiled to ensure thattheir families would have a shulhanarukh, a set table for Passover.

As women were traditionally incharge of household affairs, the Rab-bis assumed that women would takeon the task of baking matzah for theholiday. The job came with a greatdeal of responsibility—women wereentrusted to ensure that no hametz

At JOFA’s Third International Conference on Feminism & Orthodoxy in 2000, an exhibit was presented entitled A Place at the Table: An Orthodox Feminist Exploration of the Seder. The exhibit was much admired by conference participants.The texts below were originally written for that exhibit by Lisa Schlaff, Tammy Jacobowitz and Andrea Sherman.

A PLACE AT THE TABLEAn Orthodox Feminist Exploration of the Seder

he Passover seder is a communal celebration, commemorating the journeyof the Jewish people from slavery to freedom. An exploration of thePassover rituals from a feminist perspective affords contemporary Jews an

opportunity to reveal the strong women’s tradition that already exists withinJudaism. Inspired by the seder, we can enhance and enlighten our understanding ofJewish concepts and further integrate into Jewish tradition the realities of women’slives and contributions. Identifying female motifs and symbols contained within the traditional seder can stimulate discussion about the expanding spiritual andintellectual opportunities for women in Orthodox Jewish life.

Feminist ideas and images are woven throughout the fabric of our ancient her-itage. Some feminist themes intrinsic to the Passover holiday include the develop-ment of women as religious and communal leaders and the connections between thecovenantal birth of the Jewish nation, the seasonal rebirth of springtime, and thecycles of the female body. We can also pay tribute to the struggles and gains of Jewish women through the ages and in our own time, and acknowledge women asguardians, teachers and advisors of halakha. The Passover themes of birth and liberation speak both to the biological connection of women to the birthing process,and to women’s desire for freedom from their circumscribed roles.

By gathering together around a seder table of our own creation, may we deriveinspiration and strength from one another, and begin to incorporate women’s concerns as normative, rather than marginal, components of Jewish spiritual life.Harmonizing our voices with those of our foremothers, may we begin to prepare aplace for feminism at the abundant table of Jewish tradition.

contaminated the dough. The Mishnalays out rules for baking the matzah:

,uak ohab aka rnut kthknd icr /uz rjt uz ,jt rub,c ,uputu ,jtf,uexug ohab aka ohrnut ohnfju

,frug ,jtu vak ,jt ,jtf emcc(swd ohjxp) /vput ,jtu

Rabban Gamliel said: Three women mayknead the dough together, and bake in thesame oven one after another. The Rabbissaid: Three women may work with onepiece of dough, one kneading, one rolling,and one baking (Pesahim 3:4).

Entrusted with the baking of matzah,women were also responsible for riddingtheir houses of hametz. The JerusalemTalmud points to the special zeal ofwomen in performing this mitzvah:

///ohab ukhpt .nj rughc kg ihbntb kfv,uesuc ivu ,ukhmg iva hbpn ,ubntb iv (1:1 ohjxp trnd) tuva kf tuva kf

All are trusted with the responsibility ofbiur hametz, including women... Womenare especially trustworthy because they arescrupulous in performance of this task,searching every little bit, every little corner(JT Pesahim 1:1).

dopting the tasks of baking thematzah and cleaning theirhomes, women often found

that the work was backbreaking anddifficult. In the eighteenth century oneof the most famous Hasidic figuresnoticed how hard women worked tobake the matzah:

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev discov-ered that the girls who kneaded the doughfor the matzah drudged from early morn-ing until late at night. Then he cried aloudto the congregation gathered in the House of Prayer: “Those who hate Israelaccuse us of baking the unleavened bread with the blood of Christians. Butno, we bake it with the blood of Jews!”The rabbi pronounced the matzah “treif”because it was produced through oshek,the oppression of workers (M. Buber,Tales of the Hasidim).While we remember the hours upon

hours of physical labor our foremothersinvested in preparing for Passover, wealso note their spiritual contributions tothe holiday. In nineteenth century Italy,Rachel Morpurgo wrote the followingprayer, invoking our Matriarchs andexpressing her wish that the Temple berebuilt so that the people of Israel mayonce again offer the Passover sacrifice:

cuegh ejmh ovrct ubh,uct lrca hn,t lrch tuv vtku kjr vecr vra

vhjbu vfzbu ktrah ,sg kve kfjcznv hcd kg ohjxp chrevk vkgbu

ubhasen ,hc ihbcc ohaau ohjna/int ubhnhc vrvnc

May the One who blessed our ancestorsAbraham, Isaac, and Jacob, Sarah,Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, bless theentire congregation of Israel. May wemerit and live to make pilgrimages tooffer the paschal sacrifice on the altar,happy and rejoicing in the rebuilding ofour Temple, speedily in our days. Amen.(Letter dated 1850, reprinted in UgavRachel 1903)

unmg ,t ,utrk ost chhj rusu rus kfc/ohrmnn tmh tuv ukhtf

In every generation, we must see ourselves as if we went out of Egypt.

n every generation, we reclaimthe heroines and heroes of Jewish history whose visions

are truly timeless.Miriam is one such heroine. An

�

3

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

They asked of the two foods placed on theseder table, and he responded that theysymbolize the two messengers, Moses andAaron, whom God sent to Egypt. Thereare those who place a third food on theseder table in memory of Miriam, as itsays, “And I will send before you Mosesand Aaron and Miriam” (Micah 6:4).These three foods are fish, meat, and anegg, which correspond to the three types offoods Israel will eat in the world to come(Ma’aseh Roke’ach, 59).The fish was in memory of Miriam; as

both the Bible and Midrash associate herwith water, the fish is a fitting symbol. Italso recalls the fish that the Israelitewomen fed their husbands in Egypt.

idrashic tradition associatesMiriam with the well that fol-lowed the people of Israel in

the desert, quenching their thirst intime of need. Miriam’s well became asymbol of sustenance and healing forJewish people of all times, and espe-cially for women. A medieval encyclo-pedia of customs (14th c. France)records the following practice:

,ca thmunc ohn ,uksk ohabv udvbuvhrcy ka vnhc ohrn ka vrtca

kf kg ihrhzjn ,ca thmun kfutuva hn kfu /,urtc kf kgu ,ubhgn

ukhpt v,ahu ohn uk inszhu vkuj/vprb shn ihja vfun upud kf

It is the custom that women draw wateron Saturday night, as we find in theaggadah that the well of Miriam is locatedin the Sea of Tiberias. Every Saturdaynight this well taps into all the wells andsprings of the world, and all who drinkfrom this water, even if their entire body isfull of boils, will be healed (Kol Bo 41).

While Miriam is remembered as ahealer, she is also invoked as an inter-cessor. In the Yiddish tekhines (indi-vidual prayers of Ashkenazi women)the heavenly Miriam is called upon toplead on behalf of her sisters on earth:

In the merit of Miriam the Prophetess, awell of water accompanied the Jews inthe desert from the month of Iyar and on.Beloved God, remember us now in hermerit, for she sang with the women whenthe Jews went out of the Red Sea, as itstates, “Miriam the Prophetess, the sisterof Aaron, took up the drum in herhand.” Wake up, Miriam the Prophet-ess, wake up from your rest and stand infront of the King of all Kings, the HolyOne, and beg Him to have pity on us inthis month of Iyar! (Tekhine for Shabbatbefore Rosh Hodesh Iyar).

As we strive to increase women’s

involvement in Jewish spiritual life,we can look to Hasidic thought forinspiration. In the early nineteenthcentury, Rabbi Kalonymos KalmanEpstein interpreted Miriam’s danceon the banks of the sea as a symbolof the equality men and women willenjoy in the world to come:

vhvhu u,nab ekj sjt kf ie,h sh,gkrfs ,bhjc zt vhvh tku vua uevu kudhgv

vthcbv ohrn ,buuf v,hv ,tzu///tceubu ovng v,agu vhrjt ohabv kf vthmuva iht rat iuhkg rut vfhanv vzcu///,upev

/vceubu rfs ,bhjc oa In the future there will no longer be thecategories of male and female. All willcome to realize the divine light equally.This is just like a circle dance, whereevery part of the circle’s circumferenceis equidistant from the center. So willall absorb the clear light of divinityequally. This was the intention of theprophetess Miriam. She had all thewomen follow her and performed cir-cle dances with them, in order to draw

�instrumental part of the Exodus, shecarefully watched over her brotherMoses and joyously led the people insong following the crossing of the sea.While Miriam is not mentioned in theHaggadah (the name of Moses actuallyappears only once in Rabbi Yossi theGalilean’s elaboration on the number ofplagues), her story has been retoldthroughout the centuries by Jews wholook to her as a model of faith, forbear-ance, and leadership. Miriam’s song isheard once again.

The Bible tells us that Miriam “took atimbrel in her hand,” and sang:/ohc vnr ucfru xux vtd vtd hf 'vk urha Sing unto God for God is great, a horseand its chariot have drowned in the sea.However, the Bible does not record

the full text of Miriam’s song. A com-plete version of the song of Miriam wasfound among the Dead Sea Scrolls (1st c.BCE):

God, you are great, the savior, the enemy'shope has died and he is forgotten, theyhave died in the copious waters, we extolhim who raises up, and performs majesti-cally (4Q364: 6,2).

Others took note of Miriam’s absenceat the seder and strove to remember herwith ritual. A medieval collection ofresponsa preserves a dialogue betweenthe people of Kairouan and Rav SheriraGaon (10th c.):

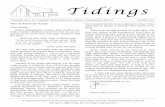

Miriam holding timbrel and women dancing at the Red Sea.The Golden Haggadah, Spain, probably Barcelona, c.1320.

British Library, Add.MS.27210, folio 15r, a.

A publication of theJewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance

Volume IV, Issue 4Spring 2004 — Nisan 5764

President:Carol Kaufman Newman

Founding President:Blu Greenberg

Executive Director:Robin Bodner

Editor:Jennifer Stern Breger

Editorial Committee:Abigail TamborMarcy Serkin

Founding Donors:Belda and Marcel Lindenbaum

Jewish Life Network / Steinhardt Foundation

The Harry Stern Family Foundation,Zelda R. Stern

JOFA Journal is published quarterly by the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, a non-profit organization. Annual member-ship—$36. Life membership—$360. All correspondence should be mailed to: Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, 15 East 26 Street, Suite 915, NY, NY 10010.We can be reached by phone at (212) 679-8500 or by email at: [email protected].

...continued on next page

4

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

upon the supernal light from the placewhere the categories of male andfemale do not exist (Ma’or va-Shemesh, B’shalakh).

uktdb ,uhbesm ohab ,ufzc/ohrmnn ubh,uct

By the merit of the righteous women, our ancestors were

redeemed from Egypt.

eep in the darkness ofEgyptian slavery, our fore-mothers caught glimpses of

light. The pyramids of hardshipsurrounding their vision did not per-suade them; they dreamt of openingsfor themselves and moved swiftlythrough them. How could theyweep at night, when a nation waswaiting to be born?

These ingenious women devisedelaborate plans to reawaken desirein their work-worn husbands. Theyfed them, bathed them, anddrenched them with sweet-smellingoils–and their magic worked won-ders. Our mothers’ wombs grew tobe as full as pomegranates. Themidrash relates that each womancould have birthed the wholenation–six hundred thousand ineach womb!

Shifrah and Pu’ah, the mighty pairof midwives, defied Pharaoh’s strictorders to ensure life continued for anew generation. Girding themselveswith the fear of God, they acted willfully and gracefully—and theywere successful.

But our mothers’ foresight andskill extended beyond the birthingroom. With Miriam as their ableguide, they greeted God’s splitting of the sea with an eruption of their own beautiful music. “Fromwhere did they have instruments in the middle of the desert?” asks the midrash. They were believers inGod’s miracles, these women andthey were prepared for redemption.

As we greet redemption at Pass-over each year, we, too, are the mid-wives of our people. Preparing ourhouses and families for the holidayis a true labor of love, fueled by fearof God and faith in the future. Allyear long, as we assume leadershiproles in our homes and in the community at large, we see new possibilities where there appears to

be darkness. We gather strength from Shifrah and Pu’ah, Miriam andYocheved, joining our forces togetherto effect change. Let us allow Miriam’ssong of praise to inspire us and guideour steps.

Maggid: Telling Our Story

eaching and learning, mesorahand kabbalah, they form thecore of the seder experience.

The halakha instructs that even if onecelebrates the Passover alone, the taleof the Exodus must still be told. Thenight’s obligations cannot be fulfilledwithout transmission, absorption,renewal. We all shine as teachers at theseder as we endlessly explore new waysto engage our children and ourselves.The chain of Jewish tradition andlearning is kept strong all year long byour teachers.

As part of this chain, Jewish womenhave long held the keys to Jewish

knowledge and tradition.Women have carefullymolded Jewish identity fortheir children, as theypassed down the intricateways of our foremothers.At times, Jewish womencould not even write theAlef-Bet, but they sharedthe wealth of knowledge,from mouths to ears.Women, along with men,are responsible for the edu-cation of their children, asthe verse says, “Listen, myson to the lessons of yourfather; do not stray fromthe Torah of your mother”(Proverbs 1:8).

Outside the home as well,women are visible as teach-ers and models of Torah.In ancient times, Miriam,Deborah, and Hannah litthe torch for the publicteaching of Torah. Today,we reclaim that early flame.Female Torah giants of ourtimes, like Nechama Lei-bowitz and Sara Schenirer,have left indelible marks onthe ways we study biblicaltexts. They did not emergefrom an unlit path. The fir-zogerins, or female prayerleaders, of Ashkenazi syna-gogues and the tenacious

female masters of Torah in Sephardilands were the forebears of our teachers.

We have only begun to witness theimpact of female teachers on our com-munity. As more women are trained inTorah study and are afforded theopportunity to share their knowledge,our community will be transformed. Asthe Haggadah says, the more we teach,the more we shall be praised.

/jcan vz hrv rpxk vcrnv kf

Matzah: Struggle and Liberation

hen extended Maggid discus-sions give way to pangs ofhunger late on the seder night,and we munch on our matzah,

we experience the freedom of the Exo-dus. Matzah, representing the bread of the Jews who fled Egypt, is primarily a symbol of liberation. We eat theunleavened bread on Passover toremember that ancient journey of free-

Miriam Chair, Miriam Stern, 2000. Part of a series on the ushpizot, the chair

was painted in a stylized manner representing Egypt. The back of the chair

depicts the Nile and the bulrushes. The front shows Miriam with a tambourine

at the Red Sea.

�

��

...continued from preceding page

Detail of Front

MIRIAM CHAIR

without ever forgetting to look back—and all around us.

Blood and Water

he mark of blood on the door-posts of theIsraelites signals

not only God’s mercy in letting danger “passover” our ancestors, butour arrival as a nation at a sacred threshold, apoint of transforma-tion, a borderline to becrossed. At this time ofyear we are summonedto “pass over” physicallyand spiritually from win-ter to spring, from dor-mancy to awakening life,from the cities of Egyptto the wilderness of Sinai,from the narrowness ofslavery to the exultationof freedom. For Jewishwomen, blood marks thecrossing of other sacredthresholds; from girl-hood to adulthood, frommaidenhood to mother-hood. Our rituals are astopping place, an oasis,the brink between therealms of the sacred andthe profane. Like theIsraelites sheltered withinthe bloodstained door-posts of their homes untiltheir passage through theredemptive waters of the

dom and to recreate the journey in ourown lives. However, matzah is also thebread of affliction, of poverty. It isbread without luxury or substance–flatand dry. A poor person, a slave, sub-sists on matzah without recourse.

In this sense, “freedom matzah” isbaked with the ingredient of slavery.Matzah reminds us of our lowly originsand humbles us. At the same time,matzah teaches us to celebrate the priv-ileges God has granted us. Jewishwomen of the late twentieth centuryare all too familiar with this type ofduality. We live with enormous free-dom and burgeoning possibility, fargreater than our foremothers couldhave imagined. Jewish scholarship andstudy are no longer closed to us. Weare day school principals, philanthro-pists, professors, and halakhic advi-sors. We may choose to congregate aswomen to pray, to celebrate RoshHodesh, to honor the bride. We are themasters of our own Jewish identities.

And yet our freedom is still limited—we incur losses on our journey. Thereare those among us who live in thechains of the agunah. We still struggleto find the solutions within our life-giv-ing halakha to release them from theirpersonal slavery. Despite our collectivegains as Jewish women, we suffer frommarginalization, rifts and misunder-standings. We search for bridges toconnect disparate groups, to foster dia-logue and create widespread change,but we still meet with difficulties onour way.

And so matzah remains a powerfulsymbol of caution amidst celebration.It pushes us to reach higher and higher,

Scene showing a father leading the seder, a male guest opposite him, and the mother with two

boys on her right and a girl on her left.Spanish Haggadah, 1350-1360. British Library,

Add.MS.14761, folio 28 v (detail).

Dedication page to haggadahcommissioned in 1816 by the Hatam Sofer, Rabbi Moshe Sofer, for his wife Serel, the

daughter of Rabbi Akiva Eiger.In the Grace after Meals, theHarachamon which usually says: “May the All Merciful One bless my wife…” here says: “May the All Merciful One bless my husband…”

Red Sea, Jewish women in niddahconstitute a holy community tem-porarily set apart until immersion inthe purifying mikvah waters.

Water, like blood, symbolizes transi-tional states of being. Intimately connected with the cycles of women’sbodies, these twin elements permeatethe threshold between our selves andthe world. Images of blood and waterinfuse the Passover seder in the fourcups of blood-red wine that some com-mentators consider represent ourmothers Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel andLeah; in the haroset, whose wine-soaked apples recall our foremothers inEgypt who conceived beneath appletrees. Rivers, wells and seas; images offeminine consciousness recur throughthe Passover story. They connect uswith the deepest meaning of the festi-val, hallowing through our ritualsGod’s essential partnership withwomen as agents of transfiguration andsalvation, and as bearers of new life.�

5

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

ase: Blessing the WineKadesh evokes images of women’s

voices, which can be heard loud andstrong, as we recite kiddush over wineon Shabbat and holidays.

.jru: Washing the HandsThe many ways water can be used

to wash away ritual impurity arefamiliar to women. Here we cele-brate the generations of women whohave served on their community’shevra kadisha, performing the finalact of kindness for their fellow sistersby cleansing them with water beforeburial.

xprf: Dipping the VegetableThe fresh green vegetables on the

seder table remind us that each springwe celebrate the earth’s ability to cre-ate life anew, and that we have newcelebrations of simhat bat and batmitzvah to welcome Jewish girls intothe community with joy.

.jh: Breaking the MatzahJust as we separate the matzah and

set apart a portion, women for cen-turies have been separating hallah. Intemple times, the separated doughwas given to the priests. As we sepa-rate hallah today, we remember thetemple and the giving hands of ourforemothers who sustained those whoserved in it.

shdn: The NarrationAs we recount the story of the Exo-

dus, we honor our mothers who sangsongs of praise after leaving Egypt.We add our voices to theirs as weserve as ba’alot hamaggid—leadersand tellers of the Passover story.

vmjr: Washing the HandsThis use of water in the seder to

wash away ritual impurity resonates inthe minds of women as we think ofour own monthly uses of the waters ofthe mikvah.

vmn thmun: Blessing theMatzah

In reciting the blessing over thematzah, we are reminded that we

may recite the hamotzi for our fami-lies each week at the Shabbat table.

rurn: Bitter HerbsAs we experience the bitter taste of

the maror, we think of the manyagunot in our community whose livesare truly embittered.

lruf: The Matzah SandwichRepresenting the uniting of the

various elements of the seder plate,korekh alludes to the uniting ofwomen’s strengths in gatherings suchas women’s tefillah and women’sRosh Hodesh groups. It may alsorepresent women uniting with men in their communities to work in part-nership to address inequities andinjustice that affect us all.

lurg ijka: The Meal As the food appears on the seder

table, our thoughts are drawn to thevarious ways in which women areinvolved with the ritual observance ofkashrut. Throughout history, womenhave been trusted in matters ofkashrut, and today, many womenturn to other women with halakhicquestions regarding kashrut and foodpreparation.

iupm: Eating the AfikomenAs the hidden portion of matzah

emerges at the end of the seder meal,we celebrate of the emergence ofwomen from the shadows of modernJewish life. We reaffirm the impor-tance of modesty in the lives of bothmen and women, even as we take onpublic communal roles.

lrc: The Blessing After MealsThe recitation of zimmun at the

beginning of birkat hamazon remindsus that women may lead and partici-pate in our own zimmunim.

kkv: PraiseAs we sing the hallel, we reflect on

the growing power of women’s voic-es, and the ways in which the voicesof Miriam, Devorah and Hannah res-onate in our lives and prayers. Wepay tribute to more inclusive minyan-im, like Shira Hadasha in Jerusalem

and Darkhei Noam in New York, forproviding a place for women to morefully participate in tefillah and com-munity leadership.

vmrb: ThanksgivingConcluding with notes of hope and

praise, the nirtzah service reminds usto be thankful for our many blessingsas Jewish women. While the strugglefor involvement of women in reli-gious ritual may be painful and slow,we learn to cherish each new gain,and are encouraged by the words“Next Year in Jerusalem.”

Young girls being instructed by elderly male teachers. Since it is

highly unusual to find such a scene in an illuminated haggadah,

scholars consider that the manuscript might have been commissioned by a woman.

The Darmstadt Haggadah, MiddleRhine, mid 15th century, folio17b.

The fourteen ritual stages of the Passover Seder are specific ceremonial acts that can help us reflect on the many rituals that enhance our lives as Jewish women throughout the year.

6

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

7

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

Two women bridge the stories ofGenesis with that of the Exodus.Both women are involved in the

birth of the nation and its redemption.They are Yocheved and Serah batAsher. Both are granddaughters ofJacob; both are identified in differentsources as the seventieth member of thefamily of Jacob to go down to Egypt.

According to the gemara in BavaBatra, Yocheved, mother of Moses,Aharon and Miriam, was conceived onthe way down to Egypt and was born“between the walls”–at the entrance toEgypt. Her face had the look of theDivine Radiance of Glory, and that wasthe meaning of her name–God’s glory.Despite Pharaoh’s decrees, Yochevedhad the faith to give birth to Moses andthen trusted in Divine Providence whenshe hid the baby in the bulrushes. Sheis also identified by the Midrash asShifrah, one of the midwives who savedthe Israelite babies during this period of great affliction. To reward her faith,we are told, she entered the Land ofIsrael at the age of 250, though none ofher children did.

Serah bat Asher is mentioned threetimes in biblical genealogies and censusfigures. According to the MidrashhaGadol and Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, itwas Serah who, in music and song, toldJacob that Joseph was still alive.(Thomas Mann in Joseph and HisBrothers describes the scene beautiful-ly.) Because Serah restored Jacob’s lifeand spirits, she lived a long life andbecame one of the few individualstaken up to heaven to enter Paradisewhile still alive. According to one ren-dition, Jacob said to her, “the mouththat told me the news that Joseph isalive will never taste death.”

Serah, like Elijah, is said have returnedthrough the ages to help the Jewish peo-ple when needed. Serah was the one whomanaged to convince the Israelites inEgypt that Moses was God’s chosenleader because she recognized in Moses’speech the special verbal signs that herfather had revealed to her. According tothe Midrash, it was also Serah who wasable to tell Moses before the Exoduswhere the bones of Joseph were locatedso that the promise to take him for bur-

ial in the Land of Israel could be ful-filled. During the reign of King David,the Midrash identifies her as the WiseWoman of Abel who managed to wardoff a rebellion without a battle by per-suading a city to surrender Sheba, a trai-tor and rebel, to Joab, David’s general.Finally, Pesikta de-Rav Kahana recordsa much later appearance of Serah inJewish history, noting that in the firstcentury C.E., it was Serah who was ableto give details of the crossing of the RedSea to Yochanan ben Zakkai and thuskeep the miracle of the Exodus accessi-ble for future generations.

Thus in Yocheved and Serah batAsher we have two transitional figuresthat according to the Midrash wereinstrumental in ensuring the future ofthe Jewish people. Both of them appearin the quite extraordinary descriptionsof women’s paradise that are found inthe Zohar, in other kabbalistic worksand in certain tekhines, where womensit together and learn Torah.

Yocheved and Serah bat Asher

Women and the Fast of the Firstborn

Traditionally, firstborn males haveobserved the fast of the firstbornon the Eve of Passover either by

fasting or by participating in a siyyumor another se’udat mitzvah, where theobligation to eat or be part of the sim-cha overides the fast. The originalsource for the fast in Tractate Soferimdoes not specify the reason for the fast,or whether the fast is limited to males.The Vilna Gaon, the Mishnah Berurahand the Arukh Hashulhan all point outthat there are two possible reasons forthe fast–either because the Israelitefirstborn were saved in Egypt orbecause of the particular holiness offirstborn males. They indicate that ifthe former reason is correct, it is equal-ly applicable to women, since womenwere also included in the miracle inEgypt, while if the latter reason is cor-rect, women would not have to fast.The assumption that women were alsosaved is based on the midrash thatrelates that Bitya, daughter of Pharaoh,was spared in the merit of Moshe,

thereby implying that other femaleEgyptian firstborn were killed. TheShulhan Arukh therefore writes:“v’yesh she’omer she’afilu nekeivabekhora mitaneh” (and some say thateven a women fasts if she is a first-born–siman 470, se’if 1). This is alsothe view of later Sephardi authorities(see haggadah of the contemporarySephardi authority, R Ovadiah Yosefwho adds leniencies for women whoare pregnant or nursing, but says that ifa firstborn woman can attend a siyyumwithout too much trouble she shoulddo so). The Maharil and the Bach wentfurther, saying that women should fastor go to a siyyum. Nevertheless, theprimary Ashkenazi authority of the six-teenth century, the Rema, writes “einhaminhag ken” (this is not the custom).While this is endorsed by some otherauthorities, it might be that attending asiyyum on Erev Pesach is a custom thatfirstborn women today should adoptsince many sources believe that womenlogically should have as much of an obli-

gation to fast as men.It is interesting that while the Rema

stated that it was not the custom forfirstborn women to fast, he consideredthat a woman should fast instead of heryoung firstborn son if the father is alsoa firstborn. The rationale is that thefather’s fast is for himself, and cannotfulfill his son's obligation as well as hisown. The Mishnah Berurah, notingthat some authorities disagree and holdthat the father’s fast can fulfill the son’sresponsibility as well, advises that whenit is very difficult for a woman to fast,there is room to be lenient and allowher not to fast. Thus it would seem thatnowadays when the general practice isto attend a siyyum and not to fast, that a mother of a firstborn child whosefather is also a firstborn should go to asiyyum on behalf of her child.

JOFA is grateful to Samuel Groner forsharing his sources and research on thistopic.

Introduction

The piyyut (liturgical hymn) Va-Yehi ba-Hazi ha-Lailah (ItWas in the Middle of the Night), sung at the seder on thefirst night, was composed by the classic liturgical poet

Yannai, whom scholars date to the 6th to 7th centuries. Thepiyyut refers to events that occurred at various times in Jewishhistory on Passover night. Most of these events involved malepersonalities. There is one indirect reference to a female figure:Danta Melekh Gerar ba-halom ha-lailah (You judged the kingof Gerar in a dream at night). This refers to Avimelekh whowas judged for “taking” Sarah on the eve of Passover (see Gen-esis, chapter 20). There is no known source for this, and it ismost probably based on the linguistic and contextual similari-ties between the Avimelekh story and that of the “taking” ofSarah by Pharaoh on the eve of Passover, which is mentionedin midrashic literature.[1]

I have composed two additional stanzas, consisting of threelines each, to Va-Yehi ba-Hazi ha-Lailah. They are based onreferences to events on the Eve of Passover involving female fig-ures that are found in midrashic literature. These stanzas arewritten in the linguistic style of the original piyyut. The womenincluded in the first stanza are Sarah, to whom the first twolines are devoted, and Rebecca. The second stanza deals withthe actual story of the Exodus as well as the Purim story. Itrefers to Rachel, an Israelite woman in Egypt before the Exo-dus, and to Bitya, daughter of Pharaoh, as well as to the Bibli-cal Esther. The traditions concerning Sarah, Rebecca andRachel all appear in Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, compiled in thefirst half of the eighth century.

The following is the Hebrew text of the extra verses, a linearEnglish translation, and a commentary.

vkhkv hmjc hvhu • It Was in the Middle of the NightAdditional Stanzas Concerning Women

By Yael Levine

Commentary:1. Sarah was also included in the Brit ben ha-Betarim

(Covenant between the Pieces) (Midrash Sekhel Tov, ed. Buber,Genesis 15:18, p.5). According to various sources, thisCovenant was established on the first night of Passover (see,inter alia, Mekhilta de-Rabbi Yishma’el, ed. Horovitz-Rabin,Bo, Masekhta de-Pisha, chapter 14, p. 51). Sarah is called Roshle-khol ha-Imahot (the Head of all the Matriarchs) in BereshitRabbati (ed. Albeck, 23:1, p. 101).

2. Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer states that Sarah was taken byPharaoh (Genesis, chapter 12) on this night (Pirkei de-RabbiEliezer, ed. Higger, chapter 26, p. 185). As already mentioned,according to the piyyut Va-Yehi ba-Hazi ha-Lailah, Sarah wasalso taken by Avimelekh (Genesis, chapter 20) on this night.

3. According to Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, the switching of theblessings between Jacob and Esau took place on Passover nightat Rebecca’s initiative (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, ed. Higger,chapter 31, pp. 197-198). Rebecca is compared to “a roseamong the thorns” (Song of Songs 2:2) because she remainedpure even though she grew up in a corrupt household (Va-YikraRabbah 23:1, ed. Margaliyyot, pp. 526-527).

4. Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer relates the plight of Rachel, anIsraelite woman in slavery in Egypt before the Exodus who isnot mentioned in the Biblical text at all. Although she wasabout to give birth, the Egyptians still forced her to makebricks by treading clay. Her child was born and became stuckin the bricks. Rachel’s cry of horror ascended to the Throne ofGlory, and that very night the angel Michael came down toearth and took the brick mould containing the baby up to God.

The Holy One, Blessed Be He, then descended “on that verynight,” and smote the firstborn of the Egyptians. Thus it wasRachel’s cry that triggered the Plague of the Firstborn and theExodus. (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, ed. Higger, chapter 47, pp. 239, 294). The term reshit onim is based on the depictionof the Exodus in Psalms 71:51.

5. This line refers to Bitya, daughter of Pharaoh, who savedMoses by night, and who, we are told in midrashic sources,was not killed in the plague of the firstborn although she wasa firstborn child (Exodus Rabbah 18:3 and parallel sources).This is connected to the verse from Eshet Hayyil (A Woman ofValor): Ta’amah ki tov sahrah, lo yikhbeh va-lailah nerah(Proverbs 31:18). In Exodus, this woman is known only as“the daughter of Pharaoh.” However, she is identified in talmudic and midrashic sources with “Bitya, daughter ofPharaoh” mentioned in Chronicles I 4:18.[2]

6. According to Midrash Panim Aherim, (ed. Buber, p. 74),Hadassah, i.e. Esther, was occupied on Passover Eve, the nightKing Ahasuerus could not sleep, with preparing a feast forHaman.

Yael Levine holds a Ph.D. from the Talmud department at Bar-Ilan University. She has published numerous articles in scien-tific journals, mainly on issues related to women and Judaism.

[1] See Mahzor Pesah, ed. Y. Fraenkel, Jerusalem 1993, p. 26. [2] See Y. Heinemann, Darkhei ha-Aggadah, Jerusalem 1970,

pp. 28-29.8

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

vkhkv hmjc hvhu

/vvkkhhkk ,uvntv atr ,t ,jycv ,hrc/vvkkhhkk ,kmv lknhctku vgrp-,hck ,kcun

/vvkkhhkkcc ,ufrcv ;hkjvk vmgh vbaua ,kuan/vvkkhhkkvv hhmmjjcc hhvvhhuu

/vvkkhhkk ohbut ,hatr ,hfvu ,skuhv vegm/vvkkhhkkcc vrb vcfh tk ,ykn vrufc

/vvkkhhkkcc inv ka u,sugxc v,hv veuxg vxsv/vvkkhhkkvv hhmmjjcc hhvvhhuu

Translation:You promised a covenant to the head of the Matriarchs at

night.She who has been taken to Pharaoh and Avimelekh you have

saved at night. She who has been likened to a rose suggested exchanging the

blessings at night.It was in the middle of the night.

The woman who gave birth cried out and you smote thefirstborn at night.

You saved a firstborn, her candle did not extinguish at night.Hadassah was busy with the feast of Haman at night.It was in the middle of the night.

9

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

shops had a different feel from those inprevious years. These workshops weregeared toward facilitated discussiongroups that were incredibly interactiveand lively. The discussion groups cen-tered around such pertinent topics asraising Orthodox feminist children, deal-ing with mikvah and sexual desire, the changing demographic of Orthodoxfamilies and the effect of gender on dating in the Orthodox community.

Gender and education played a largerole in the conference. One Sundayafternoon panel focused on Orthodoxday schools and highlighted education asa centerpiece toward future change.Participants noted that there was anenormous gap between JOFA’s work and the current attitudes and thoughtprocesses of Orthodox day schools.The panelists noted that, while the femi-nist movement has done a tremendousamount in expanding educationalopportunities for women post-highschool, there is an urgent need forgreater parity in the earlier years ofOrthodox education.

Participants were especially pleasedwith the highly successful chavruta

learning program on Sunday afternoon.A loud buzz filled the ballroom as peo-ple paired off to learn in traditionalchavruta style. The learning sessionsexplored texts involving a wide varietyof subjects, including the partnership of Mordecai and Esther, the Biblical figure of Deborah, and the Talmudiccharacter Imma Shalom. Accessibility ofall texts to all people is one of the great-est achievements of the feminist move-ment in general and JOFA in particular.The open atmosphere of the JOFA bet midrash exemplified this accom-plishment.

After a full day of programs, morethan four hundred people returned Sun-day evening for the screening of “Teho-ra” (Purity), directed by Anat Zuria. Apanel consisting of Blu Greenberg,Devora Steinmetz and Devorah Zlo-chower and moderated by Sylvia BarackFishman discussed issues of niddah froma halakhic and emotional point of view.A spirited question and answer periodfollowed.

Morning workshop elicits smiles from spirited participants.

Rabbanit Malke Bina of MaTaNresponds to questions.

Conference...continued from page 1

mesira (turning someone over to the civilauthorities) and that of hilul Hashem(desecrating God’s name). Both Rabbisconcluded that the Orthodox communi-ty and Rabbinate need to do more to protect the victims from the outset byputting a clear system in place for deal-ing with accusations of abuse and mak-ing victims feel safe coming forwardwith such accusations.

Other conference sessions reflectedJOFA’s commitment to breaking thesilence surrounding abuse within theOrthodox community. Two workshops,aimed at “Shattering the Silence” dis-cussed the sexual abuse of children in theOrthodox community. There were also anumber of sessions devoted to the agu-nah and how the community is workingto free women chained in untenablemarriages.

In an e-mail to the conference plan-ners, Rachel Keren, head of MidreshetEin Haatziv in Israel, summed up thefeeling of the conference. “I felt thisconference was an upgrading of the pre-vious ones, mainly because it gave thesense that on the basics we already standon solid ground and there is a way tomove ahead. Let us hope that a lot ofgood will result from the conference.”

Tapes of all sessions of the conferenceare available through our website atwww.jofa.org.

A crucial element in this year’s confer-ence was a panel addressing clericalabuse. Rabbi Yosef Blau and RabbiMark Dratch confronted the issuedirectly, in a panel discussion moderatedby Judy Heicklin. Rabbi Dratchaddressed three traditional mechanismsthat have been misused to silence vic-tims: directives against lashon hara(malicious gossip), the principle of

Have you visited our new website? Please be sureto check back regularly as it is constantly beingupdated. Look for the weekly d’var Torah by

Erica Brown and order the tapes from the Fifth International Conference on Feminism & Orthodoxy.

Visit JOFA’s website at:www.jofa.org

Rabbi Daniel Sperber engages in discussion with enthusiastic attendees.

Miriam’s Cup

Linda Gissen, Miriam’s Dance.Picture Courtesy of

HUC-JIR Museum, N.Y.

Women, Birth, and Death in Jewish Lawand PracticeBy Rochelle L. MillenBrandeis Series on Jewish WomenBrandeis University Press 2004 (paperback) $27.50

In this book, Rochelle Millen, Professor ofReligion at Wittenberg University,explores Jewish birth and death rituals in a comprehensive

fashion. She examines how these rituals are treated inhalakhic literature, and considers the written views of Con-servative and Reform Judaism as well as Orthodox. Sheincludes details of her own personal experiences as sheexplores issues of contraception and birth control, fertilityand birth rituals, and then of kaddish and mourning rites. Sheusefully includes complete texts of four simhat bat cere-monies. Aware of the importance of determining the place ofcustom and its authority in determining religious practice, shefocuses on the broader issues of women’s roles in Judaism andthe expansion of halakhic boundaries. In addition, sheexplores the extent to which modern day Orthodoxy recog-nizes the need for women to act publicly as autonomous individuals within the community structure. The communalcelebrations of a simhat bat for a female child and the welcome extended by many congregations to a woman whocomes to say kaddish are indications of that recognition.Millen concludes that, “The public autonomous woman must not only be tolerated, but also respected, accepted and integrated within the tradition’s view that recognizes, valuesand welcomes her full humanity.”

To Study and To Teach: The Methodology of Nechama LeibowitzBy Shmuel PeerlessUrim Publications 2004 $21.00

Nechama Leibowitz zt”l requested to beidentified on her metzevah (tomb-stone) only as “morah” — teacher. As

one of the great contemporary teachers ofTanach, she was a role model to the manywho attended her classes, studied her week-ly gilyonot (study-sheets) and read her books. While she neveridentified as a “feminist,” her influence on Jewish women ofall ages has been immense. Shmuel Peerless, one of her manystudents who knew her simply as “Nechama,” skillfully pres-ents her method of teaching and pedagogic techniques withdetailed examples from her lectures and published works. Asa teacher, her goal was to inspire a love of Torah learning andobservance of mitzvot, but there was nothing of the “feel-good” approach to texts in her teaching. Always aiming atmaking the text come alive, she modeled rigor in her methodof independent and active learning. She introduced her students to a broad range of commentators and taught themhow to use the commentaries to answer questions and resolvetextual difficulties. Nechama gave her students a competencein literary analysis that could be applied to any form of liter-

ature in any language, but most significantly opened up therichness and complexities of Torah to them all. This well-organized book will help to preserve the legacy of Nechama’steaching and provide teachers and students with the essentialskills she aimed to provide in her classroom.

Mystics, Mavericks, and Merrymakers: An IntimateJourney among Hasidic Girls By Stephanie Wellen Levine New York University Press 2003 $26.95

Stephanie Wellen Levine spent a year inCrown Heights as a Harvard PhD can-didate in American studies, examining

the world and experiences of Lubavitchgirls. She was surprised to find the girls werefar more secure, lively and full of self-esteemthan many of their peers in general society. While Levineconsiders the single-sex nature of their education and sociallife a central factor in fostering this confidence, she alsoattributes it to their specific Lubavitch mission—the beliefthat each person, male and female, has the power to bringMashiach (Messiah), and the sense of purpose in going outand “proselytizing”–bringing this message to other Jews.(Thus it is Habad in particular, rather than Hasidism or ultra-orthodoxy in general, which seems to be the determining factor in this prevalent sense of self confidence.) Levine inter-viewed 32 girls between the ages of 13 and 23. She gives usseven fascinating portraits of individual girls and youngwomen who each relate very differently to their Lubavitchcommunity and to the outside world. She concludes that theircommunity gives these girls, “a combination of comfort,direction and sense of strength that eases their lives and culti-vates a deep seated confidence.” Levine vividly portrays thesegirls, their hopes and their struggles, as well as her own feel-ings towards Orthodoxy and the Lubavitch way of life.

Women in Israel: A State of Their OwnBy Ruth Halperin-Kaddari University of Pennsylvania Press 2003$59.95

Law Professor Ruth Halperin-Kaddari,who spoke at the recent InternationalJOFA Conference, heads the Rackman

Center for the Advancement of the Status ofWomen at Bar-Ilan University. She authored Israel’s officialreport to CEDAW (the United Nations Convention on theElimination Of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women)and this book is a revised and expanded version of that study.Halperin-Kadarri explores the legal status of womenthroughout Israeli government and society, combining statis-tical data and a sociological perspective with her legaldescription and analysis. In her view, Israel lags behind otherWestern countries in concern for and sensibility towardswomen’s rights. She discusses the effect of the integration ofreligion and state on women’s lives in both public and private

10

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

Book Corner

11

JOFA

JOU

RNAL

SPRI

NG

2004

–N

ISAN

576

4

spheres. An important chapter deals with marriage and fam-ily life, detailing how Israeli family law is governed by prin-ciples of religious personal law. Halperin-Kadarri skillfullyanalyzes Jewish marriage and divorce laws, issues of childand spousal support, as well as developments in reproductivetechnology and surrogacy. She examines the possibilities forwomen’s inclusion in the rabbinical court system, assesses theeffect of women’s certification as rabbinical advocates, andanalyzes the court decisions that allowed female participationin the committees for the selection of Chief Rabbis and inmunicipal religious councils. She sees the internal mobiliza-tion of women within the religious community itself as vitalfor the movement towards change.

The Women’s Haftarah CommentaryEdited by Rabbi Elyse GoldsteinJewish Lights 2004 $39.99

While the origin of the institution ofhaftarah reading is somewhatobscure, the texts themselves are a

window into the world of “The Prophets”—the second section of the Tanakh, which

Drisha Institute for Education, New YorkDrisha has a full array of summer programs for women of allages: two Summer Institutes–a three-week program fromJune 7-25, and a five-week program from June 28-July30–with options for full-time or part-time study in Talmud,Bible, Jewish Law, Biblical Hebrew, Philosophy and Midrash.The Summer High School Program (June 28-July 30) offersteenage girls a unique experience of intensive text study com-bined with sports and cultural events. Contact Judith Tenzer,Program Director at (212)595-0307 or [email protected].

Nishmat Summer Programs, JerusalemSpeaking With and Listening to God: Prophecy and Prayer,July 4-July 22. Exciting beginner, intermediate and advancedlevel programs for women in text-based Torah learning. Forinformation and registration call the American Friends ofNishmat at (212)983-6975 or visit the Nishmat website atwww.nishmat.net.

Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies, JerusalemPardes offers two summer sessions–June 1-23 and /or July 6-29–for male and female students over the age of 19. All levels, from Beginner to Advanced, are welcome. Weeklongseminars and mini-sessions are also available. For informa-tion contact [email protected] or in the U.S. call toll free 1-888-875-2734 or write to [email protected].

MaTaN Summer Programs, JerusalemMighty Waters Cannot Extinguish Love: Exploring FamilyRelationships in Jewish Sources. Session 1; July 4-15; Session 11; July 18-29. An advanced Gemara track isoffered. Some dorm-style rooms are available in apartments.For information contact [email protected] or in the UScontact Leora Bednarsh at Tel/fax (718) 951-6421.

Midreshet Ein Hanatziv, Kibbutz Ein Hanatziv, Beit She’an ValleyWomen in the World of Torah Summer study program. Twosessions are available: June 23-30 and July 7-14. The pro-gram will be offered for both sessions with a minimum of 10participants. Study of Gemara, Tanach and ContemporaryJewish Thought in classes taught by leading Israeli instruc-tors of the Midrasha. All instructors are English speaking.Participants will be housed in Midrasha guest rooms with all meals provided in the kibbutz dining hall. Access to outdoor swimming pool and tennis courts. Tiyulim(trips) are included. For information, contact Dalia or Rachel at [email protected] or visit websitewww.midrasha.co.il.

Midreshet Lindenbaum, JerusalemThis summer program is primarily for alumnae of MidreshetLindenbaum, though a limited number of other students willbe accepted. The single session runs from June 21- July 8.Classes daily from 2-7 pm, though the Beit Midrash is avail-able all day. Morning volunteer programs will be arrangedfor those interested in conjunction with Yavneh Olami. Forfurther details and registration, email [email protected].

is their source. They are replete with prophecy and poetry,historical narratives and tales of relationships, both betweenindividuals and between the Jewish people and God. A com-panion to an earlier volume on the weekly Torah portions,this book contains insights from women rabbis on the 54weekly haftarah portions, on the readings for the specialSabbaths, and on the five megillot of the Bible also read insynagogue during the course of the year. All of the writerslook for something in the text that speaks to them directly aswomen, seeking particularly to put the female characters inperspective and exploring the imagery in the readings.Included are pieces on the special readings for holidays, a section on particular biblical women who do not appear inhaftarot and a commentary on Eshet Hayyil, the Woman ofValor. While the contributors to the volume are not Ortho-dox, there is much that we can learn from the wide-rangingcommentaries which often give a new perspective and anenlarged understanding of the readings. (JOFA is proud toremind readers of the weekly d’var Torah on our website byErica Brown that now focuses on the haftarah readings.)

snku tm • Go and LearnOpportunities for Summer Learning 2004

15 East 26th StreetSuite 915New York, NY 10010

Mission Statement of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist AllianceThe Alliance’s mission is toexpand the spiritual, ritual,intellectual, and politicalopportunities for womenwithin the framework ofhalakha. We advocate meaningful participationand equality for women infamily life, synagogues,houses of learning, andJewish communal organiza-tions to the full extent possible within halakha. Our commitment is rootedin the belief that fulfillingthis mission will enrich and uplift individual andcommunal life for all Jews.

■■ COUNT ME IN! I want to support JOFA's work and have an opportunity to be part of a community striving to expand meaningful participation for women in Jewish life.

ENCLOSED IS MY GIFT OF:■■ $2,500 ■■ $1,800 ■■ $1,000 ■■ $500 ■■ $360■■ $100 ■■ $36 ■■ Other $_______

■■ $360 or more includes Life Membership ■■ $36 or more includes Annual Membership

Name: ____________________________________________________________________

Address:___________________________________________________________________

City:____________________________________State:_______Zip: ___________________

Day Phone:__________________________Evening Phone: __________________________

■■ Check enclosed made payable to JOFA

■■ Please charge my:

■■ MasterCard ■■ Visa ■■ Amex

Card # _____________________________________ Exp. Date ____________________

Signature _______________________________________________________________

All contributions are tax deductible to the extent permitted by law. Thank you.

■■ Please include me in important updates

via email. My email address is:

_________________________________

![Portable MD Player - MiniDisc GH.pdfPanasonic alkaline: 15 hours/ 15 hours/ 15 hours Both together:26 hours/ 26 hours/ 26 hours [When the rechargeable battery (included) is fully recharged.]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5febeeab898faa4f94579279/portable-md-player-ghpdf-panasonic-alkaline-15-hours-15-hours-15-hours-both.jpg)

![Disposition and metabolism of [ c]- levomilnacipran, a ... · 1 hour, 2 hours, 2.5 hours, 3 hours, 3.5 hours, 4 hours, 5 hours, 6 hours, 8 hours, 10 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours, 48](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5f73b26d02e65a52de6394cc/disposition-and-metabolism-of-c-levomilnacipran-a-1-hour-2-hours-25.jpg)