“Paradise” Found: The Suburbanization of One Baltimore ...

Transcript of “Paradise” Found: The Suburbanization of One Baltimore ...

“Paradise” Found: The Suburbanization of One Baltimore Family

Rachel Rettaliata

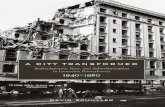

Westview Park development, aerial view of area west of Beltway, c. 1965. Photo by Morton Tadder. Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

Volume 45 Spring 2016

Editor:

Kathleen M. Barry

Numbers 3 & 4

PAGE 2 History Trails

There is a brick row home that stands on West

Lombard Street in Baltimore City. A real estate

listing might reveal that it is three stories tall, is an

end unit, and enjoys the shade of one of the many

trees on the block; it has street parking and is

conveniently located near the major highways and

the city center. Most likely, the real estate listing

would not describe this row home as average, but

that is exactly what it is. There is nothing

particularly distinctive about 819 West Lombard

Street compared to any other row home on West

Lombard Street, on the block, or in the entire city.

There are no spectacular architectural features, no

stained glass windows, and no reasons exist to give

this house a second glance—except that this row

home offers a perfect example of the urban

dwellings from which so many American families

departed in the postwar era in a mass migration to

the suburbs. Because it is average, 819 West

Lombard offers us an ideal starting point for

exploring an average family’s experience of

suburbanization. This typical family’s move from

Baltimore City to the leafier suburbs in Baltimore

County helps us put a human face on a

transformation that profoundly reshaped the city

and county, as well as the rest of Maryland and

America in the middle decades of the twentieth

century.

Dorothy Shifflett (née Hoffman) and her ten

brothers and sisters were raised at 819 West

Lombard Street. The house offered only one

bathroom for all thirteen members of the Hoffman

family, but boasted five bedrooms. There was a

small, fenced backyard for the children to play in,

“646 West Conway Street (House) & 819 West Lombard Street (House), Baltimore, Independent City, MD”: Measured

drawing by Russell Wright (undated), Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS MD-932. Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/md1042/).

SUBURBANIZATION PAGE 3

which kept them out of the streets.1 Shifflett’s

parents, Mr. and Mrs. Hoffman, had been raised in

the city and their children attended public city

schools, just as they had.2 Shifflett and her siblings

experienced a typical childhood in the city. They

would play sports in the park, socialize indoors

with friends in the parlor room, and, when they

carried on outside, they were harangued by their

crotchety old neighbor, Ms. Mary. Just to

antagonize her, Shifflett and her sisters would

swing in their backyard, loudly singing, “God Bless

Mary’s underpants!”3

Despite the charms of city life, the Hoffman

family moved from West Lombard Street in 1961.4

The Hoffmans found their new home in the

pleasant suburbs of Catonsville, Maryland, in a

neighborhood called Paradise.5 Shifflett joked, “I

guess it was ‘paradise’ to [my parents] after living

in the city.”6 Perhaps surprisingly, the spacious,

Cape Cod-style home on Prospect Avenue was

comprised of fewer rooms than the row home in the

city, but some children had grown and married by

this time and the suburbs offered amenities

that the city could not.7 In Paradise, there

was tranquility, a sense of safety, and

green space that was unparalleled in the

city.8 To Shifflett and her family, the move

from the city to suburb represented

security, comfort, and upward mobility.

The movement of families out of the

city was not unusual at the time; the

Hoffman family could have represented

any family leaving Baltimore City in the

post-World War II era. So what about this

family’s move is special or unique? The

answer is: absolutely nothing. But the

Hoffmans’ move is historically significant

precisely for its typicality, which allows us

to explore suburbanization on a personal

scale. Suburbanization exploded in the

years following World War II for many

reasons; improvements in transportation

systems, the growing affordability of

housing, and the escalation of racial

tensions all played a role in the growth of

the American suburbs. How and why the

Hoffman family relocated from the city to

the county helps us see the interplay of

these social and economic developments of the

1950s and 1960s in America.

What is Suburbia?

The vast process of suburbanization was in full

force by the time the Hoffman Family moved from

Baltimore City in 1961. The Baltimore Sun

featured countless articles and advertisements

endorsing suburban living at the time. One editorial

titled, “Act Early, Buyers Advised,” described the

boom of the housing market and averred that early

1961 would be the best time to buy a house.9 These

articles ran in the newspaper alongside pages full of

advertisements for new housing developments. One

advertisement for a community named Edgewood

Meadows promised, “This is Livin,’ beautiful trees

too!”10 Most of the advertisements for suburban

communities highlighted the “green spaces”11 and

“fresh air to breathe.”12 When asked how living in

Paradise differed from the city, Shifflett recalled

that “it was pretty out there, a lot of green trees, and

Street scene, Colonial Village in Pikeville, c. 1955.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

PAGE 4 History Trails

all that, and my father loved the ground.”13 The

Hoffman’s house on Prospect Avenue had a rolling

backyard, with an area akin to a secret garden.

There was a wrought-iron rocking bench-for-two

tucked behind huge honeysuckle and rose bushes

and a stone path that wound around the lot.

Apparently, American families did truly covet the

greenery of the suburbs and, as a result, the notion

of the picturesque suburb surrounded by nature

proved to be highly marketable for housing

developers. The lure of the suburbs caused

Baltimore County’s population to more than triple

between 1940 and 1960.14

Yet even before 1961, the suburbs were not

without their critics. In 1956, John Keats published

his cynical views on suburbanization in The Crack

in the Picture Window. Keats condemned the

shoddy workmanship of suburban housing

developers and the G.I. Bill of Rights for increasing

the affordability of housing, which allowed for the

rapid expansion of the suburbs. “You too,” Keats

wrote in his introduction, “can find a box of your

own in one of the fresh air slums we’re building

around the edges of America’s cities…you can be

certain all other houses will be precisely like yours,

inhabited by people whose age, income, number of

children, problems, habits, conversation, dress,

possessions and perhaps even blood type are

precisely like yours.”15 Similarly, leftist activist and

folk singer Malvina Reynolds wrote scathingly in

1962 of “Little boxes of ticky tacky… And they all

look just the same,” in a song called “Little

Boxes.”16 Aerial photographs of postwar suburban

housing developments like Levittown captured the

uniformity of design that critics like Keating and

Reynolds derided.

Contrary to such portrayals, however, not all

suburbs were comprised of monostylistic, low-cost

tract housing built after WWII. The Hoffmans’

house, for instance, was situated in a spacious

neighborhood, full of character and cultivated

lawns. As historian Kenneth T. Jackson made clear

in his widely influential study, Crabgrass Frontier:

The Suburbanization of the United States, there was

no single mold from which all suburbs were

created. The suburban neighborhood might come

into existence by happenstance, gradual progress,

or it could be designed intentionally.17 Jackson

surmised, “Suburbia is both a planning type and a

state of mind based on imagery and symbolism.”18

By his definition, the postwar suburbs included the

new sprawling developments that troubled critics

like Keats; but the “suburbs” also encompassed

neighborhoods formed outside of cities that varied

quite a bit from one another in ethnic diversity,

From Baltimore County Department of Public Works: Progress and Accomplishments, 1951-1957 (1958), p.89.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

SUBURBANIZATION PAGE 5

affluence, and age, among other things.19 Thus the

Hoffman family’s move to Paradise in Catonsville,

with its previously owned homes, tree-lined streets

and mature landscapes, was as much a part of

suburbanization as other families’ move to new

homes in new subdivisions across the country.

Race and Suburbanization

Although Keats’ concept of the contagiousness

of the “Levittown” suburb was exaggerated, the

neighborhood of Paradise did fit Keats’ description

in one aspect: the socio-economic uniformity

among residents.20 Paradise was inhabited by

white, lower-middle to middle class families.21 The

1960 census showed that Baltimore County overall

was nearly all white, with a mere four percent of

the population listed as non-white.22 These figures

seem almost improbable due to the high level of

disparity. However, the lack of racial diversity in

suburban communities was virtually universal in

the 1950s and 1960s.23 For example, Park Forest, a

suburb of Chicago, Illinois, did not allow a single

black family to move in until 1959.24 There were

many barriers at mid-century that prevented

African Americans from living wherever they

could afford to and wanted to live. As an economist

who studies racial issues in housing explains, these

included “racially restrictive covenants among

white property owners, biased lending practices of

banks and government institutions, strong social

norms against selling or renting property to blacks

outside established black neighborhoods, and

harassment of blacks seeking residence in

otherwise white neighborhoods.”25

The disproportionate distribution of benefits

from the G.I. Bill of Rights offers a clear example

of racial disparities in suburbanization.26 While the

Hoffman family did not directly utilize or benefit

from the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944,27

also known as the G.I. Bill of Rights, it improved

the affordability for housing by guaranteeing home

loans to veterans throughout the nation and

encouraged developers to construct more housing,

cheaply.28 The G.I. Bill made the purchasing of

homes, through taking on a mortgage,

York Road and Baltimore Beltway, aerial view, Towson, c. 1960.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

PAGE 6 History Trails

commonplace and enabled ordinary families to own

homes at an increasing rate. Unfortunately, for

servicemen of color, Veterans Administration (VA)

offices did not bequeath the benefits of the G.I. Bill

in an egalitarian fashion.29 Since fewer African

Americans served in World War II than white men,

fewer homes funded by G.I. Bill loans would have

been owned by African American families than

were owned by white families. But black veterans

were further discriminated against by the mostly

white counselors available at the VA.30 The small

numbers of black veterans who did receive loan

approval from VA counselors were often turned

down by banking institutions because “the G.I. Bill

only permitted the VA to guarantee loans, not

actually lend veterans money.”31 As a result, very

few black families were able to relocate to the

suburbs. Even if they were able to afford the move,

they were either unwelcome or logistically unable

to live too far from their children’s segregated

schools, at least until desegregation.

As more and more African Americans left the

rural South to seek better lives and opportunities in

cities over the middle decades of the twentieth

century, growing urban racial tensions also factored

in suburbanization. Such tensions would come to a

head only seven years after the Hoffman family

moved from the city, culminating in the Baltimore

Race Riots. When asked about the environment

surrounding West Lombard Street before the

Hoffman family’s move, Shifflett specified that by

1961, “the neighborhood was changing…different

kind of people were moving in and it was getting

rowdier, you know, people did not take care of their

houses as much anymore and [her] parents did not

like it there much anymore because they were

getting afraid for the children.”32 The practice of

families moving from their neighborhoods when a

“different kind of people” moved in is commonly

referred to as “white flight.” As incidents of

interracial tensions grew between 1950 and 1980,

so in turn did “white-flight communities” in the

Hutzlers Brothers Store in Towson, aerial view of store and parking lot, December 1952.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

SUBURBANIZATION PAGE 7

suburbs.33 Baltimore City public schools proceeded

with desegregation during the late 1950s and early

1960s and this, most likely, only heightened

friction within the city.34

Improvements in Transportation

Racial tensions in Baltimore did not prevent

Shifflett’s father, Richard Hoffman, from

commuting to the city for work. The conveniences

of paying a mortgage and having job stability

permitted the Hoffman family to afford living in

Baltimore County. Unexpectedly, by 1968,

employment in the suburbs was less stable than

employment in the city, mostly due to the high

concentration of young workers outside of the

cities.35 Fortunately, Hoffman worked a steady job

in the boiler room of the Bethlehem Steel

Company.36 In 1961 and the ten years previous,

Bethlehem Steel Company, according to Mark

Reutter, “had the greatest metal-making capacity

on earth.”37 Hoffman worked at Bethlehem Steel

Company during the peak of the company’s steel-

making capabilities and remained there until

retirement. At the time of their move to the

suburbs, the Hoffman family did not own a car.

When they lived in the city, Hoffman took the bus

or the streetcar to work and “if they were on strike,

he would walk” to the Bethlehem facility on Key

Highway.38 The Hoffman family would not

purchase a car for several years after their move to

Catonsville. In order to get to work, Hoffman

continued to catch the streetcar from the suburbs.39

Although the car-less Hoffman family did not

profit much if at all from the improvements to the

transportation system during the 1950s and 1960s,

the improvements benefited many Americans by

providing the option to live outside of the big cities

and commute to work. As the suburbs, private car

ownership, and commuting grew, so did the need

for a better highway system. The Federal-Aid

Highway Act, better known as the National

Interstate and Defense Highways Act, was passed

in 1956 and resulted in massive highway

construction and infrastructure improvement.40 The

National Interstate and Defense Highways Act not

only created an improved highway system, it also

fueled the evolution of the suburbs.41 After the

enhanced transportation system was implemented,

even more families could leave the city for the airy,

quiet life that the suburbs offered.

The improved transportation system may not

have been a factor that pulled the Hoffman family

into suburbia, but developments in transportation

definitely pushed the Hoffman family out of the

city. With the rise of suburban development in the

1950s and 1960s, Baltimore City suffered great

economic and business losses.42 The convenience

of suburban strip malls, the popularity of the

automobile, and the increasing ease of

transportation slashed profits in city business

districts and caused the closure of many downtown

department stores.43 The Baltimore City Planning

Commission decided to construct the beltway and

Catonsville Area Branch, Baltimore County Public Library.

Exterior view of new building, 1100 Frederick Road, August 1962.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

PAGE 8 History Trails

expressways, even before the passage of the

National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, in

order to bring business back to the Central Business

District.44

The proposed construction of Harbor City

Boulevard (now known as Martin Luther King Jr.

Boulevard) threatened to demolish the Hoffman’s

home on West Lombard Street.45 The city planned

to build Harbor City Boulevard perpendicular to

Lombard Street and the construction would split the

street in half.46 Mr. Hoffman was told that his

house would be one of those destroyed in the

process.47 By building an expressway conjoined

with Fremont Avenue, across Lombard Street and

the other parallel streets in the vicinity, the city

hoped to connect interstate highways I-395 and I-

170.48 Harbor City Boulevard also would provide

“freeway access to many of the City’s main streets,

creating access to Baltimore’s Central Business

District.”49 Under the impression that his row home

would be demolished, Hoffman took the

opportunity to move his family to greener pastures.

As it turned out, the plans to build Harbor City

Boulevard were delayed by bureaucratic wrangling

over choosing a highway system plan that most

benefitted the city.50 Eventually, the construction of

the boulevard was completed in 1982 and it was

renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.51 The

Hoffman’s old row home on West Lombard Street

was never demolished.52

Conclusion

A young couple today may search the internet

for the perfect starter home. They might stumble

upon a humble community nestled in the town of

Catonsville. The “home for sale” listings on

Prospect Avenue might capture their interest. The

rows of post-war homes on quiet, tree-lined streets

still exist. They are much older now and are even

considered “fixer-uppers.” But they have a lot of

potential. Any young couple looking to purchase

their own bit of the American Dream, a concept

cultivated through decades of suburbanization and

development, might just fall in love with the

detached houses that sit back from the winding

roads of Baltimore County, Maryland.

Had the planned construction of Harbor City

Boulevard not pushed the Hoffman family out of

the city, several other factors would have likely led

them to reach the same decision. The increasing

racial tensions that led to the Baltimore Riots of

1968 presumably encouraged the Hoffmans’ move

to the suburbs. As a family that still consisted of

school-aged children and aging parents, the specter

of violence and increasing crime rates would have

probably prompted the Hoffmans to consider

options beyond West Lombard Street in any case,

as so many other families did. With the increased

affordability of housing, the booming business of

the steel mill, and improved transportation, the

Hoffmans did indeed have alternatives to choose

among, including the house in Catonsville that they

purchased. Not every factor in the phenomenon of

suburbanization was at play in their decision to

leave their Baltimore City home for the suburbs of

Baltimore County. Their experience is only one

example of how certain factors helped to make

suburban living a widely shared goal and reality.

Did the Hoffman family find their own version

of paradise? Perhaps they found, for them, the

closest place to it. Mr. and Mrs. Hoffman lived in

their house on Prospect Avenue for the rest of their

lives. After their deaths, the house was passed

down to their youngest daughter, Penny, who lived

there for over twenty years. The story of their move

from the city to the county is a typical one. Their

eleven sons and daughters find no particular

historical significance in the move worthy of

discussion, except to revive childhood memories

from their city days. But, to us, their move shows

how the events that led to the growth of

suburbanization, as a whole, affected the decisions

of the average family. The social and economic

transformations and sweeping changes in the

transportation infrastructure of the 1950s and 1960s

created a compelling combination of push and pull

factors for the Hoffmans, as for so many other

families. And so they chose the suburban life over

the city living that they had identified with their

whole lives.

SUBURBANIZATION PAGE 9

Ingleside Shopping Center, 5600 Baltimore National Pike, Catonsville, mid-1958.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

Cromwell Valley Elementary School, Towson, under construction, c. 1962-1963.

From Construction Photos between February 3, 1962 & March 2, 1963 by Foster Photography.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

PAGE 10 History Trails

Map of “Urban Communities in Baltimore County,” from Planning in Baltimore County:

An Information Booklet (Office of Planning and Zoning, Towson, Maryland, 1968), p. 4.

Collections of the Historical Society of Baltimore County

SUBURBANIZATION PAGE 11

Notes 1 Dorothy Shifflett, interview by author, Catonsville, MD,

November 11, 2012. 2 Shifflett interview. 3 Shifflett interview. 4 Shifflett interview. 5 Shifflett interview. 6 Shifflett interview. 7 Shifflett interview. 8 Shifflett interview. 9 Editorial, “Act Early, Buyers Advised,” Baltimore Sun,

January 2, 1961. 10 Advertisement, “This is Livin,’” Baltimore Sun, January 2,

1961. 11 Advertisement, “Howard County: Land of Opportunity,”

Baltimore Sun, March 13, 1961. 12 Advertisement, “There’s Plenty of Room for Everyone,”

Baltimore Sun, January 6, 1961. 13 Shifflett interview. 14 Neal A. Brooks and Eric G. Rockel, A History of Baltimore

County (Towson, MD: Friends of the Towson Library, 1979),

369. 15 John Keats, The Crack in the Picture Window (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1956), xi. 16Malvina Reynolds, “Little Boxes,” lyrics reprinted in

Charles H. Smith and Nancy Schimmel, Malvina Reynolds:

Song Lyrics and Poems, accessed April 26, 2016,

http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/MALVINA/mr094.htm. 17 Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The

Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1985), 3-11. 18 Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier, 4-5. 19 Ibid., 5. 20 Museum label for “Shapes of the Suburbs,” American on the

Move, Smithsonian National Museum of American History,

Washington, D.C. [viewed November 2, 2012]. 21 U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population:

1960, Vol. I, Part 22, Maryland (Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Office, 1961), Table 33. 22 Ibid., Table 27. 23 Museum label for “Diversity in the Suburbs,” American on

the Move, Smithsonian National Museum of American

History, Washington, D.C. [viewed November 2, 2012]. 24 Ibid. 25 William Collins, “Fair Housing Laws,” EH.Net

Encyclopedia, ed. Robert Whaples, February 10, 2008,

accessed April 27, 2016, http://eh.net/encyclopedia/fair-

housing-laws. 26 David H. Onkst, “‘First a Negro…Incidentally a Veteran’:

Black World War Two Veterans and the G.I. Bill of Rights in

the Deep South, 1944-1948,” Journal of Social History 31, n.

3 (1998), 522-523. 27 An act to provide Federal Government aid for the

readjustment in civilian life of returning World War II

veterans, June 22,1944 ; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of

Congress, 1789-1996; General Records of the United States

Government; Record Group 11; National Archives, accessed

November 11, 2012, Access to Archival Databases at

www.archives.gov. 28 Keats, The Crack in the Picture Window, xiii. 29 Onkst, “‘First a Negro…Incidentally a Veteran,’” 521-520. 30 Ibid.

31 Onkst, “‘First a Negro…Incidentally a Veteran,’” 522. 32 Shifflett interview. 33 Rachael A. Woldoff, White Flight/Black Flight: The

Dynamics of Racial Change in an American Neighborhood

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011), 3. 34 Maryland State Department of Education, A Decade of

Progress in Education in Maryland: 1949-1959 (Baltimore:

State Department of Education, 1961). 35 Thomas M. Stanback and Richard V. Knight,

Suburbanization and the City (Montclair: Allandheld, Osmun

& Co., 1976), 124-125. 36 Shifflett interview. 37 Mark Reutter, Making Steel: Sparrows Point and the Rise

and Ruin of American Industrial Might (New York: Summit

Books, 1988), 7. 38 Shifflett interview. 39 Shifflett interview. 40 Museum label for “On the Interstate, 1956-1990,” American

on the Move, Smithsonian National Museum of American

History, Washington, D.C. [viewed November 2, 2012]. 41 Ibid. 42 Terry Wikberg, "Building Baltimore: The Baltimore City

Interstate Highway System," Maryland Legal History

Publications 13 (2000), 4. 43 Museum label for “The Sprawling Metropolis,” America on

the Move, Smithsonian National Museum of American

History, Washington, D.C. [viewed November 2, 2012]. 44 Wikberg, “Building Baltimore,” 4. 45 Wikberg, “Building Baltimore,” 12. 46 Ibid. 47 Shifflett interview. 48 Wikberg, “Building Baltimore,” 17. 49 Ibid. 50 Wikberg, “Building Baltimore,” 13. 51Wikberg, “Building Baltimore,” 17. 52 Shifflett interview.

PAGE 12 History Trails

About the Author

Rachel Rettaliata is a 2014 graduate of UMBC

with a degree in History and International Affairs.

This article is a revised version of a semester-long

family history research paper, written under the

guidance of History Department Chair, Dr.

Marjoleine Kars. Rachel is currently an intern with

Preservation Maryland and a Fulbright Scholarship

recipient. As a Fulbright Fellow, she will spend the

2016-2017 academic year conducting historical

research on national monuments in the Republic of

Moldova. Rachel will return to the United States in

fall 2017 as a graduate student in University of

Maryland, College Park's Historic Preservation

program.

Board of Directors

Tom Graf, President

Dale Kirchner, Vice President

H. David Delluomo, CPA, Treasurer

Phyllis Bailey

Brian Cooper

Evart ‘Bud’ Cornell

Geraldine Diamond

Edward R. English, III

John Gasparini

John Gontrum

Jeff Higdon

Len Kennedy

Larry Trainor

Vicki Young

Honorary Board

Hon. Helen D. Bentley

Louis Diggs

Robert Dubel, Ph. D.

Adrienne Jones

Charles Scheeler

Submissions

While the subject matter of History Trails has

traditionally focused almost entirely on local

concerns, we are interested in expanding its scope

into new areas. For example, where one article

might focus on a single historic building, person, or

event in the county, others may develop and defend

a historic argument, compare and contrast

Baltimore County topics to other locales, or tie

seemingly confined local topics to larger events.

Articles abiding by the Chicago Manual of Style

Documentary Note (or Humanities) system will be

given priority. For an abbreviated guide to Chicago-

style citations, see Kate L. Turabian's A Manual for

Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and

Dissertations (University of Chicago Press, 2007;

http://www.press.uchicago.edu/books/turabian/turab

ian_citationguide.html).

Digital and/or hard copies of articles may be

submitted to the attention of the History Trails

editor at the address below. E-mailed and digital

copies are preferred.

9811 Van Buren Lane

Cockeysville, MD 21030

(Phone) 410-666-1878

(Web) www.hsobc.org

(Email) [email protected]

Find us on social media:

![CWS ParadiseLine. · 2019-04-02 · 12 ] Paradise Air Bar 13 ] Paradise Seatcleaner 14 ] Paradise Toiletpaper 15 ] Paradise Superroll 16 ] Paradise Paper Bin 17 ] Paradise Ladycare](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5f4d115eb47f9811753b5af9/cws-2019-04-02-12-paradise-air-bar-13-paradise-seatcleaner-14-paradise.jpg)