Panther Legacy Magazine

-

Upload

mosi-ngozi-fka-james-harris -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Panther Legacy Magazine

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

1/36

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

2/36

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

3/36

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaklsdfjEDITORIAL

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaldh3PANTHER LEGACY

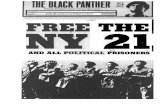

This magazine Panther Legacy- has been puttogether by the Black Panther Commemora-tion Committee in time for the visit to Lon-don of Emory Douglas, former Minister ofCulture of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence, and Billy X Jennings, head of theBlack Panther Alumni.

It is an honour to welcome these Brothers inorder to spread the legacy of the Panthersand to raise money for the Black PantherAlumni projects. It is the very least that theBPCC can do, indebted as we are to the ex-ample and sacrice by the members of theBlack Panthers on behalf of oppressed peo-ple in the US and across the world.

Whereas many people will know somethingof the Panthers due to frequent references inpopular culture, especially in Hip-Hop, manypeople do not necessarily have an under-standing of what the Panthers stood for andwhat happened to the organisation. We hopethat this publication will be a tool for learningas to the legacy of the Black Panthers, theircommitment to ideology and struggle tobetter the conditions of their/our peoples.

The Black Panthers in the US made an impor-tant contribution to developing the worldstruggle against oppression and racism in thelate 1960s and 1970s. The post-Second WorldWar period saw a massive upsurge in the

worldwide struggle with the newly estab-lished socialist countries in East Europe,north Korea and China assisting by everymeans Third World anti-imperialist strugglessuch as those in Vietnam, South Africa, Cuba,Algeria, Egypt, Mozambique, Namibia, Zim-babwe and many other places. The BlackPanthers were a part of this global struggle.

The Black Panthers in the US were an exam-ple of a radical grassroots movement forrevolutionary change within the West itself.The Panthers along with many other move-ments in the Black Liberation Movement andtheir allies amongst the movements in theNative American, Hispanic, Chinese, and

radical White left communities, had achievedthe highest level of mass revolutionary strug-gle in the US.

The Panthers understood hat they had aunique internationalist duty, as their strugglewas positioned within the US, the countrywhich was conducting a world oensiveagainst Third World peoples and socialistcountries. As the Field Marshall of the BlackPanther Party, George Jackson (murdered byprison guards in Soledad prison in August1971) stated in his Prison Diaries in 1970; Theentire colonial world is watching the blacksinside the U.S., wondering and waiting for us to

come to our senses. Their problems and strug-gles with the Amerikan monster are much more

dicult than they would be if we actively aidedthem. We are on the inside. We are the onlyones (besides the very small white minority left)who can get at the monsters heart withoutsubjecting the world to nuclear re. We have amomentous historical role to act out if we will.

The students and intellectuals who wererebelling were tamed in the 1960s and 70s.The white working class were also manipu-lated by the elites through racism to dividethe masses. In contrast oppressed peoples inthe West, such as those represented by thePanthers played and continue to play a fun-damental role in developing the struggle fora people-centred society: one which treats

working people with dignity and a societywhich compensates Third World peoples forthe holocausts committed against them bythe Western elites, and opens up a new era ofrespect and friendship with them.

To those of us who are committed to pro-gressive change, the Panthers remain animportant experience to learn from. Thereare also other examples of struggle in theWest. Some of these struggles and move-ments were crushed while others have stead-ily developed their socialist and anti-imperialist strategies such as the people inIreland, Ireland being a colony of Englandsfor over 800 years. For us in England, Scot-

land and Wales, the struggle of the Irish Re-publicans remains another primary referencefor our struggles today. They are taking upthe same challenges in their communitiesthat we face in our communities. The dier-ence between us and them is that they havea political movement whereas we dont. Andthis remains a central issue for us in Englandwhere the movement is next to non-existentfor the masses of people in our communities:to learn the lessons of the Panthers, as part ofthe experience of oppressed people through-out the world, and apply it in our the presentconditions.

We also have important struggles from the

Scottish, Welsh and Black and Asian workingclass struggles to learn from. The experiencesin Brixton, Southall, Ladbroke Grove/NottingHill, Toxteth, Bristol, Handsworth and manyother communities as well as the Great Min-ers Strike of 1984-85 remain important recenthistories whose lessons, both positive andnegative, need to be returned to time andtime again.

For people today confronting problems ofIslamophobia, war and racism in all its forms,homophobia and sexism, poverty and youth-on-youth crime in our communities, the ex-

periences and initiatives of the Black Pan-thers in the US deserved to be looked at very

closely. The challenge remains today as it wasin George Jacksons time, as the former FieldMarshall stated: The whole world for all timein the future will love us and remember us asthe righteous people who made it possible forthe world to live on. If we fail through fear andlack of aggressive imagination, then the slavesof the future will curse us, as we sometimescurse those of yesterday. I dont want to die andleave a few sad songs and a hump in theground as my only monument. I want to leave aworld that is liberated from trash, pollution,racism, nation-states, nation-state wars andarmies, from pomp, bigotry, parochialism, athousand dierent brands of untruth, and li-centious usurious economics.

Indeed we in the BPCC salute those whostruggled and sacriced in the worldwideBlack Panther movement. We will keep onkeeping on.

Sukant ChandanLondon, November 2008

ABOUT US

The Black Panther Commemoration Commit-tee in England consists of people from dier-ent political experiences and backgroundswho came together in the September 2008united in the belief that the Black PantherParty for Self Defence was one of the mostimportant experiences of oppressed people'ssocial, political and cultural struggle in theWest.

AIMS

The BPCC work towards keeping the experi-ence and legacy of the Black Panthers alivefor current and future generations.

The BPCC support the excellent work of theBlack Panther Alumni.

The BPCC support and work towards cam-paigning for justice and liberation of politicalprisoners who were associated with the BlackPanthers.

The BPCC understands that the Black Pan-thers had an international impact, and webelieve in raising consciousness about theexperiences and legacy of the Black Panthersacross the world, and especially here in Eng-land.

blackpanther1966.blogspot.com

EDITORIAL

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

4/36

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

5/36

Why honour the rank and le members

and who were these members?

The answers to these questions arefound by remembering and giving rec-ognition to those who actually did thework and who really made the BlackPanther Party Programs happen.

The reality is that the average Partymember was between the ages of 18 to20 years old. These young Party mem-bers worked long and very hard hoursboth day and night without any pay.They lived collectively and shared al-most everything with their fellow Pan-ther members. They owned nothing andfor the most part their closest relation-ships were with their comrades.

These young Panthers rose at dawn andworked until their assigned jobs weredone. They functioned for the peopleand for their communities. They shoul-dered the tasks of cooking breakfasts forschool children and working in the com-munities soliciting donations in order tokeep those programs supplied. Theywent door-to-door, gathering signaturesfor petitions on issues that aected theircommunities and educating those com-munities on those same issues. Theycollected clothes for the free clothingprogram.

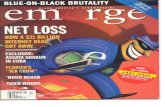

Very importantly, there was the job ofselling the Black Panther Party Newspa-pers, which they did every daydoor-to-door, on college campuses, in bars,restaurants, clubs, bus stations, and onstreet corners. This work brought on theharassment of the police, includingarrests and time in jail. Even imprisonedthey worked to politically educate andrecruit inmates to join the Black PantherParty.

At the end of the day, these young Pan-thers were expected to read the BlackPanther Party Newspaper cover-to-cover. They also had to attend politicaleducation classes as well as rallies anddemonstrations. They were expected tomemorize and understand the Partys 10Point Party Program and Platform, theThree Main Rules of Discipline, and theRules of the Black Panther Party.

The rank and le members of the BlackPanther Party forged new revolutionaryways of thinking and demonstrated newways of behaving. They developed and

practiced the art of collective thinkingby casting aside egotism and arrogance.

The

We became more important than theI.

These were no easy tasks, but for therank and le members of the Black Pan-ther Party to accomplish them on a na-tional level, among poor, Black, disen-franchised, and oppressed people, weremonumental and astounding revolu-tionary achievements.ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE AND ALLPOWER TO THE RANK AND FILE MEM-BERS OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY.

Elbert "Big Man" Howard, one of the origi-

nal six members of the Black PantherParty, served as the Party's deputy ministerof information and as a member of theInternational Solidarity Committee. Hewas the founding editor of the Party'snewspaper, the Black Panther Party Com-munity News Service. Howards Pantheron the Prowl is available by sending amoney order for 15 US dollars to him andthe DVD A History of the Black PantherParty is available for $20He can be emailed at:

Honouring the Rank and File Members of the Black Panther Party

Elbert Big Man Howard

hfdhhkkdfkdmnviornfvkdfkasdfklhhhHONOURING THE RANK AND FILE MEMBERS

Elbert Big Man Howard

OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY

hgfdhjhgkjkjfkdmnviorgfjkasdjfkljdsfalohhin5PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

6/36

The Black Panther Party is not a blackracist organization, not a racist organiza-tion at all. We understand where racismcomes from. Our Minister of Defense,Huey P. Newton, has taught us to under-stand that we have to oppose all kinds ofracism. The Party understands the imbed-ded racism in a large part of white Amer-ica and it understands that the very smallcults that sprout up every now and thenin the black community have a basicallyblack racist philosophy.

The Black Panther Party would not stoopto the low, scurvy level of a Ku Klux Klans-man, a white supremacist, or the so-called"patriotic" white citizens organizations,which hate black people because of thecolor of their skin. Even though somewhite citizens organizations will stand upand say, "Oh, we don't hate black people.It's just that we're not gonna let blackpeople do this, and we're not gonna letblack people do that." This is scurvydemagoguery, and the basis of it is theold racism of tabooing everything, and

especially of tabooing the body. Theblack man's mind was stripped by thesocial environment, by the decadentsocial environment he was subjected toin slavery and in the years after the so-called Emancipation Proclamation. Blackpeople, brown people, Chinese people,and Vietnamese people are called gooks,spicks, niggers, and other derogatorynames.

What the Black Panther Party has done inessence is to call for an alliance and coali-tion with all of the people and organiza-

tions who want to move against thepower structure. It is the power structurewho are the pigs and hogs, who havebeen robbing the people; the avaricious,demagogic ruling-class elite who movethe pigs upon our heads and who orderthem to do so as a means of maintainingtheir same old exploitation.

In the days of worldwide capitalistic im-perialism, with that imperialism alsomanifested right here in America againstmany dierent peoples, we nd it neces-sary, as human beings, to oppose miscon-

ceptions of the day, like integration.

If people want to integrate - and I'm as-suming they will fty or 100 years fromnow - that's their business. But right nowwe have the problem of a ruling-classsystem that perpetuates racism and usesracism as a key to maintain its capitalisticexploitation. They use blacks, especiallythe blacks who come out of the collegesand the elite class system, because theseblacks have a tendency to ock toward ablack racism which is parallel to the ra-cism the Ku Klux Klan or white citizensgroups practice.

It's obvious that trying to ght re withre means there's going to be a lot ofburning. The best way to ght re is withwater because water douses the re. Thewater is the solidarity of the people's rightto defend themselves together in opposi-tion to a vicious monster. Whatever isgood for the man, can't be good for us.Whatever is good for the capitalistic rul-ing-class system, can't be good for themasses of the people.

We, the Black Panther Party, see ourselvesas a nation within a nation, but not forany racist reasons. We see it as a necessityfor us to progress as human beings andlive on the face of this earth along with

other people. We do not ght racism withracism. We ght racism with solidarity.We do not ght exploitative capitalismwith black capitalism. We ght capitalismwith basic socialism. And we do not ghtimperialism with more imperialism. Weght imperialism with proletarian interna-tionalism. These principles are very func-tional for the Party. They're very practical,humanistic, and necessary. They shouldbe understood by the masses of the peo-ple.

We don't use our guns, we have never

used our guns to go into the white com-munity to shoot up white people. Weonly defend ourselves against anybody,be they black, blue, green, or red, whoattacks us unjustly and tries to murder usand kill us for implementing our pro-grams. All in all, I think people can seefrom our past practice, that ours is not aracist organization but a very progressiverevolutionary party.

Those who want to obscure the strugglewith ethnic dierences are the ones whoare aiding and maintaining the exploita-

tion of the masses of the people: poorwhites, poor blacks, browns, red Indians,poor Chinese and Japanese, and theworkers at large.

Racism and ethnic dierences allow thepower structure to exploit the masses ofworkers in this country, because that's thekey by which they maintain their control.To divide the people and conquer them isthe objective of the power structure. It'sthe ruling class, the very small minority,the few avaricious, demagogic hogs andrats who control and infest the govern-ment. The ruling class and their runningdogs, their lackeys, their bootlickers, their

Toms and their black racists, their culturalnationalists - they're all the running dogsof the ruling class. These are the oneswho help to maintain and aid the powerstructure by perpetuating their racistattitudes and using racism as a means todivide the people. But it's really the small,minority ruling class that is dominating,exploiting, and oppressing the workingand laboring people.

All of us are laboring-class people, em-ployed or unemployed, and our unity hasgot to be based on the practical necessi-ties of life, liberty, and the pursuit of hap-piness, if that means anything to any-body. It's got to be based on the practicalthings like the survival of people andpeople's right to self-determination, toiron out the problems that exist. So inessence it is not at all a race struggle.We're rapidly educating people to this. Inour view it is a class struggle between themassive proletarian working class and thesmall, minority ruling class. Working-classpeople of all colors must unite against theexploitative, oppressive ruling class. So letme emphasize again - we believe ourght is a class struggle and not a racestruggle.

hgfdhjhgkdmnviorgfvkdfkasdjfkljdsfaklhhilohWHY THE PANTHERS ARE NOT RACISTSTaken from Bobby Seales Seize The Time

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgn6 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

7/36

40 years onand the BlackPanthers stillprovide inspira-tion and les-sons for youngprogressivepolitical activ-ists.

The 1960s wasa time of greatsocial changeand upheaval,with the CubanRevolution inits infancy, theCold War at its

height, the daily massacres in Vietnambeing ashed across television screens,and the black civil rights movement inthe US steamrolling forward.

In the north of Ireland, young people,students, workers and those who could-nt get a job, joined together to demandcivil rights, they where inspired by thepositive and deant actions of the blackcommunity in the USA.

The fraternal links between the Irish and

black Americans have historic links, withan escaped black slave Frederick Douglasarriving in Ireland in 1845, to campaignin support for the anti slavery movementin the US, receiving backing from DanielOConnell.

The 1960s was a time to take action,struggles across the globe showed thatthey could only be won by confrontingthe oppressor and making the demandsfelt loud and clear.

Against this backdrop, an organisation inOakland, California, the Black Panthersarose in defence of the Black communityand to ensure that civil rights be

achieved and the racism that oppressed,and marginalised their people be con-fronted and ended.

Throughout the civil rights movement inthe USA, the white supremacists understate orders, and in state uniforms, batoncharged, brutalised, jailed and even mur-dered those who marched in support ofequal rights for the black community, asimilar trait that would later manifest onthe streets of Belfast, Tyrone and Derry.

Defence for the black community wasneeded in such times, and the Black

Panthers stood up and where countedwhen their people needed them. Thiswas a major factor in a huge upsurge insupport for the edgling organisationwhich soon spread, empowering blackpeople and communities across the USA.

The Black Panthers, where not simply adefence movement, yet placed commu-nity led socialism at the very heart oftheir struggle, they believed in organisedempowered communities, where citizenswhere cared for and accommodated on aneeds basis. They soon began to organ-ise many community projects, which

enhanced and built a community spirit,and while providing training, and educa-tion, they also provided food kitchens,and refuge for the most needy in theircommunities.

While many in the Black Panthers whereMarxist-Leninist, they did not stick rigidlyor dogmatically to Marxs teachings, andvery much applied their ideology in amodern pragmatic context.

Irish Republicans similarly organisedtheir struggle through the oppressednationalist ghettos in the north, andwhile our ultimate objective is a 32County Socialist Republic, when the

Provisional IRA arose in 1969, their pri-mary role was in defence of the national-ist community who where being sub-jected to genocide, with whole national-ist streets being burned out and manybeing brutalised and murdered by un-ionist death squads aided by the unioniststate.

The simi-larities inthe re-sponse byboth theUnionistState and

US au-thoritiesare shock-ing.

Indeed theBlack Pan-thers kepta close eyeto Ireland,theemergingcivil rightsand war of

national liberation, with KathleenCleaver of the Black Panthers saying atthe time, All our sympathies were withthe IRA -- even with the Provisionals --because they took such a clear-cut posi-tion on armed struggle,"

The Black Panthers received massive andsustained harassment and repressionfrom the US authorities, and coupledwith that it has been widely suggestedthat the State allowed and even directeda huge inux of narcotics into black com-munities in order to destroy any attemptat an organised and empowered com-

munity, the same has been said of BritishIntelligence in Ireland, with drug dealersreceiving immunity in return for theirattempts at disempowering communi-ties and passing on information.

While the Black Panthers no longer existas an organisation, their ideology andlegacy prevails, they stand as a monu-ment to Black Power, and a risen peoplewho confronted the state head on, ex-posing their institutionalised racism andensuring that it could never happenagain.

The Black Panthers played a huge role inbuilding condence and empowering of

the black and working class communitiesnot only in America, but across theglobe.

Barry McColgan is national organiser of SinnFein Youth / Ogra Shinn Fein.He can be contacted at:

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnissopopokljdsfaklsshhhkh

A RISEN PEOPLEThe Panthers and the Irish freedom struggleBarry McColgan

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnrgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsf7PANTHER LEGACYFredrick Douglas mural in West Belfast, northern Ireland

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

8/36

Olive Morriswas an activemember ofthe BrixtonBlack PantherMovementuntil thegroup dis-solved andreformedinto a num-ber of organi-

sations working on specic aspects

within the Black struggle.

The Black Panther and the Black PowerMovements in Britain developed fromthe work of the Universal Coloured Peo-ples Association. Several American BlackPanthers and radical activists visited theUK and gave lectures in London, includ-ing Malcom X (1965), Stokely Carmichealand Angela Davis (both in 1967). Theirmessage struck a chord in second gen-eration Black youth, and gave impulse tothe formation of a local Movement.

The British Black Panther Movement,although inspired by the ideology of theUS Black Panther Party, was a dierent

type of organisation that responded tothe specic reality of Black people in theBritain. As an organised movement itwas short lived, and its main period ofactivity was from 1970-1973. Don Lett, amember of the Movement explains thedierence in an interview by Greg Whit-eld, published by http://www.punk77.co.uk

It all seems so easy now, the very wordjust rolls o your tongue, Black British,but for awhile back there, it wasnt sosimple you know? Fundamentally theBlack British and the Black Americanexperience was dierent, right from

source. Black Americans were dragged,screaming and kicking, from the shoresof Africa to an utterly hostile America,whilst my parents, they bought a ticketon the The Windrush bound for Lon-don! So, right o, you have it there, amajor fundamental dierence. So eventhough I attended the Black Panthermeetings, proudly wearing my AngelaDavis badge, read Soul on Ice, therewas still so much more that we neededto do. Its true that we became aware,became conscious in many respects andthat was partly due to those Panther

ideologies, but the total relevance ofthat movement just didnt translate intothe Black British experience.

The Black Panther Movement organiseditself in groups based around a particu-lar location or area, and each grouporganised and run their work and activi-ties independently but overseen by acommon centre core. This central core -the intellectual leadership of the move-ment made up of university students -organised the setting up of local groupsin areas with a large Black population,

and recruited local working class youththat constituted the local core.

Many members of the Brixton groupwent on to become inspiring commu-nity leaders and became notorious g-ures in their eld of work. The BrixtonPanthers had their headquarters atShakespeare Road in a house that wasbought with money donated by JohnBerger when he won the Bookers Prize.

Here are some of the members of theBrixton Black Panthers:

Althea Jones - medical doctorFarukh Dhondi - broadcaster and writer

David Udah - church ministerDarcus Howe - broadcasterKeith Spencer - community activistLeila Hussain - community activistOlive Morris - community activistLiz Turnbull - community activistMala Sen - authorBeverly Bryan - academic and writerLinton Kwesi Johnson - writer and musi-cianNeil Kenlock - photographer and foun-der of Choice FM London

This quote from an interview with LintonKwesi Johnson published in 1998 byClassical Reggae Interviews, describesthe work and ethos of the Brixton Black

Panthers:

It was an organization that came in tocombat racial oppression, to combatpolice brutality, to combat injustices inthe courts against black people, to com-bat discrimination at the place of work,to combat the mis-education of blackyouths and black young people.

The Black Panther movement was not aseparatist organization like Louis Farra-khans Nation Of Islam. We didnt be-lieve in anything like that. Our slogan

was Black Power - Peoples Power

and we also realized that we had tolive in the same world as white peopleand that if we wanted to make somechanges we had to win some supportfrom the progressive section of thewhite population.

We published a newspaper which wewould sell on the streets. I used to dothat myself. Every Saturday morning Ihad to go to Brixton Market, CroydonMarket, Ballem Market, wherever().

We would organize campaignsaround specic incidents where therewas some racial injustice involving thepolice and so on. We had educationalclasses for the Youth Section (I wasmember of the Youth Section) where westudied Black History, Politics and Cul-ture.

And as a matter of fact it was throughmy involvement with the Black Panthermovement I discovered Black Literatureread a book called The Souls Of BlackFolk by W.E.B. Dubois and got inspiredto write poetry.

When in time the Black Workers Move-ment dissolved, its members used theexperience they have gained to set upnew organisations, such as Black Work-ers Movement, the Race Today Collec-tive and the Brixton Black WomensGroup. Olive Morris was a foundingmember of the BWG and OWAAD, andmaintained close ties to both organisa-tions throughout her life, even while shewas based in Manchester.

If you or someone you know was in-volved with the Brixton Black Panthersand have stories or pictures of that timethat you are willing to share please getin touch, in particular if you have any

memories of Olive Morris work in theMovement.

Ana Laura Lopez de la Torre is an artist fromUruguay, based in London since 1996. AnaLaura is currently working on two public artprojects in South London, where she lives. AnaLaura de la Torre is part of the Remember OliveCollective -http://rememberolivemorris.wordpress.com -and can be contacted at:

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmngnfvkdhfjkasdjfkljdsflh

OLIVE MORRIS: A PANTHER IN BRIXTON

Ana Laura Lopez de la Torre

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgn8 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

9/36

OliveMorris

speaking

atarallyagainstpoliceb

rutalityoutsideBrixtonLibrary(ca.

1972)

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

10/36

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

11/36

In all the places that Ive been I thinkthat West Indian people are probablythe most abandoned people in theworld. Abandoned by their host coun-try and abandoned by their own coun-try too.Michael X - 1967

We have always taken our idea of whatit means to be black from the Ameri-cans.

Right now we are all black and whitewaiting for Obama to dene themeaning of Race in the world today. Ifhe becomes president what will thatmean that being black is no longer aproblem? If he doesnt does thatmean the West is still a racist place,that perhaps America - or any countryis ready will ever be ready for a blackhead of state.

Weve always looked across the Atlan-tic for understanding of identity andfor solutions.

In the 50s and 60s around the time of'want a nigger for your neighbour votelabour ' and No Irish, no dogs, noblacks black people took their cuefrom Publicised riots, lynchings andsegregation in America in terms oftheir options. After meeting MalcolmX. A young Michael de Freitas, a pimp,Rachman [Ladbroke Grove landlord-editor] hardman and gambler,changed his name to Michael AbdulMalik and decided he was going tobring about social change in Britain.

This was echoed by the media whoimmediately baptised him Michael X

after Malcolm, they were lookingacross Atlantic too - to nd a point ofreference Brits could understand.

It is interesting and it is very sad thatwe do this. Interesting because this iswhere Michael De Freitas found theinspiration to say some very importantthings about what it means to be ablack man in Britain. He understoodthat it was a dierent experience toAmerica, hence his thought provokingcomment above, despite the fact thatat that time he made it black Ameri-

cans were sitting at the backs ofbuses.

However, it is sad because our experi-ence is not dened by what happensin America.

Black British people have very dier-ent histories, cultures and even lan-guages compared to African Ameri-cans. We also livein very dierentsocieties. We needto look to our-selves for theanswers.

In America blackhistory is wellknown and evencelebratedthrough legen-dary works such asAmistad and Be-loved and ColourPurple.

Where are ours?We too had a richand complex his-tory. We too hadour legends and

our heroes. Wealso had a civilrights movementand importantleaders. Unfortu-nately we dontknow it enough dont celebrate itenough. We knowmore about Mar-tin Luther Kingthan MarcusGarvey never

mind that Garvey died in Kensington.Most of us dont even know who Mi-chael X, Claudia Jones or AnthonyLester.

Positive identity is the starting pointfor self-improvement and you canttruly know yourself, unless you under-stand where and what you have comefrom.

Vanessa Walters is a UK writer. She haswritten two novels, Rude Girls and BestThings in Life. She has had several plays

staged around the UK. She has recentlypublished 'Smoke! Othello!' a poetrycollection about Afro-Caribbean experi-ence in West London. Her latest play'Michael X' is on at The Tabernacle, Not-ting Hill Gate, London from 6th Novem-ber.www.carnivalvillage.org.uk for bookingsor call box oce on 0871 271 51 51

What does it mean to be black and British?

Vanessa Walters

Michael X

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnrgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfakluhnWHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE BLACK AND BRITISH?

Vanessa Walters

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljh11PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

12/36

While Nga Tamatoa wasthe radical group foryoung Maori in the '70s,the Polynesian Pantherswas the outlet for youngPacic Island agitators.

Originally formed inAuckland in June 1971 asthe Polynesian PantherMovement, the organisa-tion was a fusion ofyoung Pacic Island stu-

dent radicals and their gang member cousins.

Director of Pacic Island Studies at Auckland University, DrMelanie Anae, quoted this passage from Panther material, ina 2004 "Anew" article to highlight the group's outlook.

The revolution we openly rap about is one of total change.The revolution is one to liberate us from racism, oppressionand capitalism. We see many of our problems of oppressionand racism are tools of this society's outlook based on capi-talism; hence for total change one must change society alto-gether.

Their Marxism was like that of their US based Black Pantherheroes: Maoist oriented. The Panthers also reached out tovariety of radical allies.

The PPM (known the Polynesian Panther Party, after Novem-ber 1972) allied with the Maori radicals

of Nga Tamatoa and the Maoists of Roger Fowler's PeoplesUnion and the NZ Race Relation's Council, HART and theCommunist Party.

They also mixed with the Trotskyists from the Socialist ActionLeague and with members of the Pro-Soviet, Socialist UnityParty.

The Panthers worked closely with the Marxist controlledCitizen's Association for Racial Equality and the AucklandCommittee on Racial discrimination (ACORD).

In July 1973, PPP "Minister of Culture" Ama Rauhihi attendeda Maoist "People's Forum" in Singapore and was selected totour China with several Maori members of the CommunistParty of NZ.

In July/August 1974, PPP member Norman Tuiasau attendedthe 10th International Youth Festival in East Berlin. The con-ference was convened by the Soviet front, World Federationof Democratic Youth and the trip was organised by the So-cialist Unity Party.

Tuiasau heard US Communist Party leader, Angela Davis,speak in East Berlin and traveled on to Moscow where he sawLenin's tomb.

The Panthers delegated a young Melanie Anae to make con-

tact with the real Black Panthers, during a trip to Los Angelesto stay with relatives. In September 1974 an article on thePPP was published in "Black Panther" magazine in the USA.

In mid 1972, PPP leader Will 'Ilolahia toured Australia wherehe met Aboriginal Black Power groups. On his return he an-nounced plans for "solidarity and co-operation" between thePPP, Aboriginal groups and black power supporters inPapua-New Guinea.

At their peak, the Panthers had a busy HQ in Ponsonby,Auckland, several branches across the city, a shortlivedbranch in Dunedin and supporters in other centres.

lhgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaklshPOLYNESIAN BLACK PANTHERSSina Brown-Davis

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgn12 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

13/36

The PPP was very active forseveral years. They randances for youth, agitatedfor trac lights at unsafepedestrian crossings, ranfood banks, organisedprison visits and ran candi-dates for local high schoolboards.

More politically, in 1972,the PPP worked with NgaTamatoa, the Stormtrooperand Headhunter gangs toform a "loose PolynesianFront"

In January 1974 the PPPparticipated in a meeting

"amongst all Maori andPolynesian progressive organisations to form aunited front".

Understandably the PPP focussed on exposingracism, particularly by the police. In 1974, thePPP, jointly with Nga Tamatoa, CARE, ACORDand the Peoples Union organised the PoliceInvestigation Group, which mounted "P.I.G.patrols" to monitor police dealings with Poly-nesian youth.

The PPP's military wing also assisted in theParty's several campaigns against rack renterswho allegedly preyed on the Polynesian com-munities at the time.

The PPP was active until the late '70s and neverocially disbanded. Several cadres were ar-rested at Bastion Point in 1978 and some evenplayed a role in the "Patu" squad during the1981 Springbok Tour.

The legacy of the Panthers lives on in Aotearoa today.Younger generations have beneted from the struggle thatour elders engaged in during the 60s 70s & 80s. Still how-ever there is much to do and still much oppression felt byour brothers and sisters in the Pacic and world-wide. Statusin white society and the material comfort of some of us doesnot negate the fact that the majority of Pacic peoples livelives of racism & poverty. The best legacy we can leave forthe Polynesian Panthers is to rekindle the struggle and ght

against oppression in our communities & our islands.

Sina Brown-Davis is a descendant of Te Roroa, Te Uri o Hau,Ngapuhi, Fale Ula & Vava'u tribes. She is an indigenous Activist,Mother & Blogger, and can be contacted [email protected]

Patu squad from the 1981 Springbok tour

Polynesian Panthers Ponsonby Auckland 1970

Emory Douglas & Gary Foley ( long time Aboriginal Activist)

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaldh13PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

14/36

For some the Black Panthers representa romantic revolutionary brand - some-

thing to put on a t-shirt. However justlike Brother Malcolm/Udham Singh/TipuSultan etc and many others, their ap-pearance on the political scene caused aseismic change: it was the beginning of

the end of White Supremacy,although we continue to ghtfor its end.

We can and should have a dis-course about whether MartinLuther King or Ghandi for thatmatter were really non-violentpacists. This depends if you seewords as ammunition or theprojection of these giants of thecivil rights movement as manu-factured by those who have aninterest in letting people ofcolour know that they cannot beviolent, that violence is a mo-nopolised by "white folks".

The notion that those oppressed,slaughtered and enslaved shouldsomehow limit themselves topeaceful struggle whilst theoppressor has no boundaries totheir violence is comical if not arepulsive. The price for dogmaticand rigid non-violence is alwaystoo high for the oppressed.

When the arrival of something far moreradical starts to emerge that's when anunjust system begins to shake and theemergence of the Black Panther Partywas a turning point that did indeedshake the system.

In the corridors of that despicable worldpower, the US government, the windwas really blowing them into a panic. Itwas inconceivable or incomprehensiblethat those they had murdered for yearswithout any remorse might be able todefend themselves from their murder-ers, these murderers being usually thepolice.

Turning the other cheek came at a highprice for the African-Americans. Whitesupremacy works on many levels andthe US government were the masters ofit along with the Brits, essentially per-petuating a cowardly system whichworks on continuing and increasinginjustice. When it is faced with confron-tation from the oppressed it runs behinda mask of compromise and negotiation,maintaining its privilege and positionbut giving the impression that it some-how has seen the light. In history youwill not nd any white holocausts butmany black ones.

All the apparatus of the State went towork against the Panthers, yet the Pan-thers grew with great speed and thatcan only happen when there is a massappetite for justice and also the massfeeling that there are scores to settle.Enough is enough" and an "eye for aneye" really got those turkies in Washing-ton working overtime. Cointelpro was

put into action. The pro-gramme says it all, the deceitof the power structure and theparanoia.

The Black Panther Party historyis written but look in betweenthe lines and you see an or-ganisation and a movementthat shook the established

order far more than what wasprobably intended when HueyNewton and Bobby Seale setup the Party. The Panthersshowed that just a littleplaying outside of the boxcan move the biggest devilsinto panic. They were perhapsthe Hizbullah or Hamas of theirtime!

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmhgnfvkdfjkjfkljdsfaklsdfjh

THE HAMAS AND HIZBULLAH OF THEIR TIME

Aki Nawaz of Fun-Da-Mental

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhgkjkdjfkdmnn14 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

15/36

"We realize that some people who happen to be Jewish and whosupport Israel will use the Black Panther Partys position that isagainst imperialism and against the agents of the imperialist asan attack of anti-Semitism. We think that is a backbiting racistunderhanded tactic and we will treat it as such. We have respectfor all people, and we have respect for the right of any people toexist. So we want the Palestinian people and the Jewish peopleto live in harmony together. We support the Palestinians juststruggle for liberation one hundred percent. We will go on doingthis, and we would like for all of the progressive people of theworld to join our ranks in order to make a world in which all peo-

ple can live."

(On the Middle East, Huey Newton)

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnrgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljodsfa

HUEY NEWTON:

WE SUPPORT THE PALESTINIANS 100%

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaldh15PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

16/36

Thirty-six years ago in rural Louisi-ana, a white guard was murdered inthe State Penitentiary; then re-garded as the bloodiest and mostbrutal prison in the United States.

The violence wasnt unusual in thisdeep pocket of Louisiana. Back inthe 1800s, slaves worked on theplantation; now a predominantlyAfrican-American inmate popula-tion cultivates the crops grown onthe sprawling expanse of the prison,

also known as Angola, after the country that provided theAmericas with most of its slaves.

Black Panthers Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox were atthe prison convicted on unrelated charges of armed rob-bery on that April morning in 1972 when Brent Miller wasstabbed to death.

Born activists, Wallace and Woodfox founded the only recog-

nised Black Panther chapter inside a prison to combat theirdegrading environment. Shortly after their arrival in Angola,they spoke out against inhumane treatment such as system-atic rape; united inmates in solidarity; and attempted to putan end to racial segregation. They also organised a well-publicised non-violent hunger strike with the aim of securingbetter conditions.

Our greatest campaign, I would say, was when we formedanti-rape squads, trying to protect the young men that wascoming into the prison systemWe just said no more,Woodfox told POCC Block Report Radio this year. As danger-ous as it was, we thought the risk of injury or death was worthit, and so we decided to take action. We fought against the

open racism, the horrible conditions, lack of adequate cloth-ing, lack of adequate food, the brutality, just about every formof corruption in this prison that was going on.

As Woodfox and Wallace waged their campaign, they beganto capture attention from the outside. The two men weresubsequently convicted, in 1973 and 1974 respectively, ofMillers murder, though no physical evidence has ever linkedthem to the crime.

The men were charged on the basis of bribed testimony.Bloody ngerprints at the scene of the murder did not matchtheirs, and ocials have refused to check them against theprisoner ngerprint database to nd the real killer. Numerousalibi witnesses came forward in their defence, while prisonerswho testied against them have recanted their testimony and

admitted they were coerced by ocials to lie under oath.

The men, known collectively with the now freed Robert Kingas the Angola 3, have languished in Angola prison ever since.

The three have, however, succeeded in steering an interna-tional coalition to raise awareness of their cases and those ofothers in Angola and to secure their freedom. King, releasedin 2001 after his conviction for another murder at the prisonwas overturned, speaks around the world on their behalf. Hehas just released his autobiography, Cry from the Bottom ofthe Heap, about his time at Angola.

Recent momentum in the campaign has been undeniable.Until March this year, Wallace and Woodfox were held insome of the most punitive conditions of the notorious 18,000-

acre complex by the Mississippi River, spending up to 24hours a day in spartan cells, with little human contact or otherdistractions.

However, after an upsurge in media attention and an un-precedented visit to Angola by John Conyers, chair of the UShouse judiciary committee, which oversees the justice depart-ment (including the FBI) and the federal courts, prison ocialsswiftly moved the men out of solitary, after almost 36 years,into a maximum-security dormitory.

One month later, Conyers wrote to FBI director Robert Muellerrequesting FBI documents relating to the case. In his letter, he

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfakhANGOLA PRISON, LOUISIANA:

Helen Kinsella

MODERN-DAY SLAVE PLANTATION

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhldjfkdmnviorgn16 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

17/36

stated that he was deeply troubled by what evidencesuggests was a tragic miscarriage of justice with re-gard to these men.

Amnesty International has also weighed in on the

Angola 3. Last year, they described the mens treat-ment as cruel, inhuman and degrading, and said thattheir prolonged isolation breached the InternationalCovenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Con-vention against Torture.

This autumn, the campaign has had what may be itsbiggest success yet. Last month, a federal judgemade the spectacular decision to overturn Woodfoxsconviction, despite State appeals, on the basis ofevidence of prosecutorial misconduct, inadequaterepresentation, and racial discrimination, in his 1973trial. The ruling acknowledged that Woodfox hadbeen wrongfully imprisoned.

Though that means that he is no longer convicted of

the murder of Brent Miller, due to legal complexities,that decision does not automatically set Woodfoxfree. The State has appealed the judgement, and attime of going to print, Woodfox is waiting to hear ifhe will be released on bail.

Woodfox has demonstrated the deep aws in thestate's investigation and prosecution of the caseagainst him, and has presented evidence of his inno-cence, Chris Aberle, one of Woodfox's lawyers, saidon hearing the ruling. If the State of Louisiana ap-peals, it will bear the burden of showing the court ofappeals that both of the judges [a magistrate judgepreviously ruled in his favour] were incorrect. As thefacts and the law are so clearly on the side of Mr.Woodfox, we are condent that the State cannotcarry that burden. No further legal delay should de-prive Albert of even one more day of his life.

If Woodfox is released, campaigners hope that Wal-lace will also walk into freedom, given that the caseagainst him rests on the same evidence.

The International Coalition to Free the Angola 3 draws muchof its support from Europe, where grassroots campaignershave been raising awareness of the mens plight as well asthat of another inmate at Angola, Kenny Zulu Whitmore, a54-year-old who has spent more than 31 years in solitaryconnement.

Zulu, also aliated with the BPP, was convicted of murderand armed robbery in 1977 and immediately placed in soli-tary at Angola. He believes he was framed for speaking out

against police abuse in his community. On arriving at Angola,he was immediately placed in solitary, and has remainedthere ever since, barring interludes of months at a time in thecrushing prison dungeon.

Artist and activist Carrie Reichardt, aka The Baroness, serves asa spokesperson and tireless campaigner for the London chap-ter of the A3 Coalition and the Free Zulu campaign.

In June this year, she unveiled a spectacular mosaic on theoutside wall of her house and studio (called The TreatmentRooms) in the west London suburb of Chiswick to raise aware-ness of, and give honour to, the men, to whom she frequentlywrites.

The colourful public artwork, which took four months to cre-ate, is the latest in a series of mosaics adorning The TreatmentRooms.

She is also keen to expose her 11-year-old daughter to politi-cal activism. In August this year, Poppy stepped inside thegates of Angola to visit Woodfox and Wallace, eating friedchicken and ice-cream with men the State wishes would re-main hidden forever.

Herman and Albert have been waiting for justice for nearlyfour decades, Reichardt said. We wont stop ghting untilthey are out. But there are many more men like them in An-gola and across the US. Zulu has spent all of his twenties,thirties, forties and now into his fties locked in a 6x9 foot cell.As far as Im concerned, the laws that keep him there do notequal justice.

Helen Kinsella is a freelance writer in London, working in mediaand for non-prot organisations. She campaigns with grassrootsmovements, including the Angola 3, whom she has representedat the United Nations. She can be contacted at :

Albert,PoppyandHerman

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnrgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfa17PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

18/36

The scene irresistibly evokes Tupac'srevolutionary roots: When he was a fewdays old, Tupac was taken to his rstpolitical speech, given by "Minister LouisFarrakhan at the 168th Street Armory inNew York." That was the rst time I sawhim says Karen Lee, then a black militantwho, in another twist of fate, served asTupac's publicist nearly twenty years

later. "He was a little baby with big eyes.They were the rst things you couldsee." Those big eyes and the world theyenvisioned made Tupac the hip-hopJames Baldwin: an excruciatingly consci-entious scribe whose narratives amedwith moral outrage at black suering.Tupac imbibed his disdain for racialoppression from his mother's revolu-tionary womb. As Tupac's godfather,Black Panther Elmer "Geronimo" Prattremarks, the artist "was born into themovement

That birthright of black nationalismhung over Tupac's head as both promise

and judgment. Some saw him as thebenighted successor to Huey, Eldridge,Bobby, and other bright stars of blacksubversion. In this light Tupac's careerwas best imagined in strictly politicalterms: Rapping was race-war by othermeans. Others see the Black Panthers asa strident symbol of political destructionturned inward. This would mean thatTupac's violent lyrics and wild behaviorsuggest the ethical poverty of romanticnationalism. Tupac initially embracedthe former view, though he quickly wea-

ried of the aesthetic and economic im-peratives it imposed. As he won fameand money, he brooked no ideologicallimits on what he could say and how hecould live. But even as he exchangedrevolutionary self-seriousness for thethug life, he never embraced the notionthat the Panthers were emblematic ofpolitical self-destruction. To be sure,Tupac saw thug life extending Pantherbeliefs in self-defense and class rebel-lion. But he never balked at Panther

ideals. The practices, as we shall seeshortly, were another matter.'

The boosters and critics of the Panthersalike agree that Tupac was problematic.It is an agreement, however, stamped inirony. Each side nds Tupac unaccept-able for the same reasons they nd eachother's views intolerable, even repre-hensible. Panther purists claim that-Tupac's extravagant materialism anddeant hedonism are the death knell ofpolitical conscience, the ultimate selloutof revolutionary ideals. Critics of themovement contend that Tupac's thugfantasies fullled the submerged logic of

Panther gangsterism, what with its sex-ual abuse of women nancial malfea-sance, and brutal factionalism. In eithercase Tupac is the conicted metaphor ofblack revolution's large aspirations andfailed agendas. Early in his short life hesought to conform practical survival torevolutionary idealism. Later he reversedthe trend.

To borrow W. E. B. DuBois's notion ofdual consciousness, in Tupac two war-ring ideals were (w)rapped in one darkbody. The question to ask now is: CouldTupac's dogged strength alone havekept him from being torn asunder? In

hindsight a negative answer seems cer-tain, though perhaps disingenuous. Itwas perilous enough for old heads to tryto reconcile competing views of blackinsurgence, as proved by gures as dif-ferent as Malcolm X and Huey Newton.How much wisdom could one expectfrom an artist who barely lived beyondhis twenty-fth birthday, even thoughhe was hugely talented and precociousto a fault? It is a testament to his gargan-tuan gifts-and to our desperate need,which after all, screams so loudly be-

cause of our failure to nd suitable an-swers-that the expectation existed at all.Our best chance of understanding Tu-pac's dilemmas, and his failures andtriumphs, too, rests in probing the idealswith which he was reared and thatshaped his life for better and for worse.What did it mean to be a child of theBlack Panthers, to have a post-revolutionary childhood?'

In explaining his ministerial vocation,

Martin Luther K ing Jr. remarked that hisfather, grandfather, and great-grandfather were preachers. "I didn'thave much choice, I guess," he humor-ously concluded. Although Tupac's revo-lutionary lineage is not as long, it isequally populous and perhaps morestoried. He was surrounded by guresthat lived and died the struggle for blackfreedom. Afeni and her lovers Lumumbaand Billy Garland were Black Panthers.Tupac's stepfather, Mutulu Shakur, anacupuncturist and black revolutionary,was sentenced in 1988 to sixty years inprison for conspiracy to commit armedrobbery and murder. He was also found

guilty of attempting to break Tupac's"aunt" Joanne Chesimard, later knownas Assata Shakur, out of prison, whereshe was sent in 1977 after being con-victed of murdering a New jersey statetrooper. And Tupac's godfather,Geronimo Pratt, loomed large as a he-roic gure. From the very beginning,Tupac was, as Pratt says, "fascinatedwith the history of that which he wasborn into.' "

In the haunting footage of Tupac atschool at age seventeen, he conrmsPratt's impression. "My mother was aBlack Panther, and she was really in-

volved in the movement," Tupac says."Just black people bettering themselvesand things like that." And from the start,Afeni's role in the movement was costly,limiting, in Tupac's mind, the time shespent with him. "At rst I rebelledagainst her because she was in a move-ment and we never spent time togetherbecause she was always speaking andgoing to colleges and everything," Tu-pac says. But after a period of intensemovement activity, Tupac and hismother bonded. "And then after that

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnrgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaklsdfhTUPAC SHAKUR: "THE SON OF A PANTHER"Extraxct from Holler If You Hear: Me Searching for Tupac ShakurMichael Eric Dyson

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgn18 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

19/36

was over, it was more time spent withme and R was] just like, 'You're mymother,' and she was like, 'You're myson.' So then she was really close withme and really strict on me."

Even as a youth, Tupac discerned theprice paid for revolutionary principles,especially when one had little money."Being poor and having this philosophyis worse," Tupac says. But he brilliantlyanalyzes the dierence between nan-cial and moral wealth. "Because youknow if money was nothing, if there wasno money and everything depended onyour moral standards and the way thatyou behaved and the way you treatedpeople, we'd be millionaires. We'd berich." Ever the realist, Tupac prescientlysizes up his family's situation, especiallythe cost of critical thinking spurred by

revolutionary beliefs. "But since it's notlike that, then we're stone broke. We'rejust poor because our ideals always getin the way, 'cause we're not 'yup-yup'people." Tupac knows that taking criticalinventory of one's surroundings doesnot make for job security, though headmits that he's bitter about being poorfor his principles, since he missed "outon a lot of things" and because "I can'talways have what I want or even thingsthat I think I need." That does not keephim from dissecting the futility of manywealthy people's lives. "But I know richpeople, or people just well-o, who arelost, who are lost." For that reason, hismother's sacricial choices really havepaid o. "She could have [chosen] to goto college and get a degree in some-thing and right now [could have] beenwell-o. But she chose to analyze societyand ght and do things better. So this isthe payo. And she always tells me thatthe payo to her is that me and my sis-ter grew up good and we have goodminds and ... we're ready for society."

Tupac admits that his mother, by havinggone " through the sixties," is cool-headed and more inclined to say, "Letme think about this rst and then do it,because I know how that happens." Buthe also recognizes that her noble eortsare often harshly repaid. Tupac claimshis family moved from New York"because of my mother's [political]choices. And she couldn't keep her jobbecause of her choices, because it wastoo much.... They gured out who shewas and she couldn't keep a job. Thatshould be illegal." It is almost impossiblefor those who have never been undersurveillance by the government or had

their families shattered by political har-assment to comprehend the veil of sus-picion, skepticism, and of course para-noia that hangs between hounded po-litical activists and the rest of the world.

We now know that many governmentagencies covertly and corruptly tried todestroy the black freedom movement,from the Southern Christian LeadershipConference to the Black Panthers.'

The Panthers' example inspired Tupac toaddress racial conict. Discussing a ghtbetween skinheads and black youth at aparty in Marin City, seventeen-year-oldTupac says he and his friends tried to"gure out what to do." Concluding that"this couldn't happen in the sixties"without a response from black activists,Tupac and his friends decided that "we'llstart the Black Panthers again." Tupac

says that unlike the Panthers of the1960s, "we're doing it more to t ourviews: less violent and more silent."There would be "more knowledge tohelp" with the restoration of black pride."I feel like if you can't respect yourself,then you can't respect your race, thenyou can't respect another's race. . . . Itjust has to do with respect, like mymother taught me." By starring the BlackPanthers again, Tupac ,in(] his comradeswould not only teach black pride butinstil the value of education as a meansof self-defense and as a safeguardagainst bigotry. By doing this, theywould harken back to a turn-of-the-century strategy adopted by DuBois Therevived Black Panthers would function"as a defense mechanism [against] theskinheads, because that'swrong, and I hate to feel help-less," Tupac explains. "And soskinheads hate black peopleand ... I have this vision of usjust growing, and them de-creasing, because that's howknowledge works. It's conta-gious, you know. And if there[are] war and peace, peacewins out." Tupac says he will"learn from our mistakes. AndI'm talking to a lot of the ex-members of the Panthers fromthe sixties now, because they'reless violent. You know, they'velearned." Tupac is quick, how-ever, to underscore their vir-tues. "They did a lot of goodthings in the past, and we cando a lot of good things. . .. Mymother was an ex-Panther, and[we'll be] talking to GeronimoPratt, and a lot of ex-ministersof defense. So we're going todo a lot of good."

Contrary to the caustic criticism he laterreceived, Tupac was not drawn to thePanthers because of their stylized vio-lence, their hyper-masculinized images,

or their alluring social mystique. Hisattraction to the Black Panthers was apractical attempt to answer racial op-pression. The embrace of black pridewas not for compensatory or therapeu-tic ends. Rather, its purpose was, rst,self-respect and, then, respect of others.It was self-regarding morality linked toother-regarding social concern.

For all of his reveling in Panther racialtheories, Tupac was far less enthusiasticabout their contradictory practices.Tupac was especially wounded because

he felt the party unjustly abandoned hismother at her most needy moments. IfTupac grew bitter about the povertyAfeni's ideals brought about, he wasequally bitter about the failure of thePanthers, for whom she sacriced familyand career, to oer help. As they toutedanti-capitalist beliefs, some of the party'schief icons lived luxuriously, even disso-lutely, at the expense of the proletarianrank and le. If such practices appeareddistasteful from a distance, up close theywere downright ugly. Afeni remembersthat her children inherited her sacricialspirit. "If they had too many [toys], theygave them away," Afeni recalls, "and Iwas not rich." Their practice reectedher belief that "everything should go tothe community." She says that receiving

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaldh19PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

20/36

her "training from the movement"made her believe that ... capitalism' wasa dirty word." Tupac, however, haddierent ideas. He "had a logical mind,"Afeni says, and thus examined her situa-tion without the ideological trappingsthat bound her. But according to Afeni,Tupac "really resented the fact" of herbetrayal by the party. Afeni remembersthat Tupac wanted desperately to arguewith godfather Geronimo Pratt, but outof respect he held his tongue. Tupac feltless favorable about other members."Other people who were in the party, hereally didn't have a lot of respect for,"Afeni says. "Because he was a child whowas there. He knew what they did andwhat they didn't do. And I never ed tomy kids ... for better or for worse. That isbasically the way we lived our lives, so

they knew exactly what was going on inour lives as it was happening. And theyknew who wasn't there and who left usand who never bothered to help." Afenibelieves that Tupac saw the contradic-

tions, and "he did stand in judgment."But she quickly adds, "He loved theprinciples. It wasn't the principles thathe was mad at." Instead, it "was the lackof courage in the face of " suering thatriled him, especially the hurt it causedthe movement's female soldiers.

Many male Panthers chose, or wereforced, to leave behind children andwomen. The government's repressivetechniques destroyed many activistblack families, often dividing fathersand mothers from their kin. In fact, Tu-pac was constantly approached atschool by FBI agents seeking the where-abouts of his stepfather, Mutulu Shakur.Tupac was grieved by the gruesomepattern of family abandonment he wit-nessed, perhaps reminding him of his

own desperate plight. Afeni says thatfrom the perspective of a child suchevents were surely painful. "When youtalk about the pain that the child felt,especially when you realize that you

can't changeit, it is hard,"she says. "It issuch a deepplace." A placeso deep that itobviously lefta permanentscar on hisconscience,leaving Tupac

with the beliefthat onecould be-infact, shouldbe-a rich revo-lutionary. Ifrevolutioncan't pay thebills-or, moreprecisely, ifthose revolu-tionaries whoare the move-ment's breadand buttercan't keep

their headsabove water-then the revo-lution hasalready failed.Afeni says thatin Tupac'seyes,---notonly was[the] revolu-tion not pay-ing the bills,but it was

causing a great deal of disaster for me."Tupac therefore taught Afeni to makepeace with money. "I think I am learninghow to live in a capitalist society, whichI did not know how to do," she says."But I learned that from Tupac. I didn'tknow how to do that. I just knew how tobe mad with capitalism Tupac, accord-ing to Afeni, learned to rebel and makecash, a lesson she slowly absorbed. "Itnever occurred to me," she says. "I nevergave myself permission to do that. . . .He released me from so much. . . . Tupacwould challenge the [things] that I heldsacred. He would make me think aboutthem."

If Tupac demanded that his revolution-ary forebears consider the conse-quences of their failed practices, he also

challenged artistic communities andthe entertainment industry to face upto their equally heinous contradictions.Free from the bruising environmentthat trumped revolutionary ideology,Tupac appeared free to embrace itsworthier elements. It was evident fromthe start of his edgling career thatTupac wasn't simply play-acting thepart of a revolutionary, even if his ex-cesses sometimes made him appearextreme, even self-destructive. "Hemade me think," says Danyel Smith,former editor of Vibe Magazine whowas a twenty-four-year-old strugglingwriter when she met eighteen-year-old

Tupac in Oakland. "Even before he wasfamous, and even more so after he wasfamous, and began to really write thekind of songs that were in his heart,"Tupac made "you question whateverline you were riding on." Smith says thatshe would have been happy simply tohave a job whether at Kinko's or thedepartment store, and "Tupac wouldsay, 'Why are you working for the whitepeople?' Now you know, people havesaid that throughout history to blackpeople: 'We were slaves to the whitepeople; we need to start our businesses;why are you working for the whiteman?"' But the way Tupac would say it

made it appear to Smith Eke a new,urgent, even inescapable quest don.'And then I would be sitting there reallysaying to my~ self, 'Should I really beworking for white people?... Smith saysthat Tupac had "an absolute truth forhimself, which is appealing in anybodybecause it's so rare."

hgfldthhrbzeuiiipkkyuerfgajdfiiiiiiiiiilpaojhgkjkdjfkdmnh20 PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

21/36

Unity in the Community!Black Power to Black People!

White Power to White People!

Brown Power to Brown People!

Yellow Power to Yellow People!

Red Power to Red People!

These phrases were the cries that emanatedfrom Black communities throughout thisnation they were initiated by the BlackPanther Party in 1968. Many organizationswere formed after hearing and rallyingaround those calls, including the PatriotParty, the Young Lords, the Brown Berets,

the Red Guard, and the American IndianMovement.

Who were these groups and how did theycome into existence?

The Patriots were a group of white working-class and poor young people which origi-nally formed in Chicago and many of themoriginated from street-turf gangs. Theirchapters and Ten Point Program were mod-eled after the Black Panther Partys and theywere strong supporters of the Black PantherParty. They closely followed the Black Pan-ther Partys example and dedicated them-selves to serving the basic needs of theircommunities, such as feeding hungry chil-dren with free breakfast programs. Manyworked to establish free health clinics andother services in their communities. ThePatriot Party, like the Panthers, published anewspaper.

The Young Lords also followed, in purposeand actions, many of the examples set bythe Black Panther Party. These young PuertoRicans formed chapters in Philadelphia,Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New Jersey,Boston Massachusetts, and Puerto Rico.

Their female leadership strongly pursuedthe ght for womens rights and formed andworked with prison solidarity groups forincarcerated Puerto Ricans. By 1976, theYoung Lords had been all but destroyed bythe FBI. However, their impact remained other groups formed and continued to pur-sue their goals.

San Franciscos Red Guard was patternedclosely after the Black Panther Party. In 1969,the federal government wanted to shutdown a Tuberculosis testing center locatedin San Franciscos Chinese community. Atthe time, Chinatown had the highest TB ratein the country. The young Asians in the RedGuard organized the community and stagedsuccessful protest demonstrations to keepthat TB testing center open. Through these

protests and the programs that the RedGuard initiated, Chinatowns citizens wereenlightened and became open to moreprogressive politics.

In 1970, members of the Red Guard werepart of a delegation that was invited to joinEldridge Cleaver and they accompanied himin a visit to China, North Korea, and NorthVietnam. After about two and a half years,due to political and police repression, suchas oce raids, arrests without warrants, falsearrest, and armed stand-os with police, theorganization collapsed.

Cesar Chavezs United Farm Workersbrought attention to the plight of Hispanicfarm workers in this country. Because of hisinuence, and that of the Black PantherPartys, young Chicanos from the barrioscame to realize that struggle against oppres-sive conditions was necessary for change,and the Brown Berets organization wasformed in 1967. The Brown Berets had a 13Point Party Platform similar to that of theBPP. In the summer of 1968, the Brown Be-rets marched with the Rainbow Coalition inthe Poor Peoples Campaign in Washington,DC. Among their many contributions, theyorganized Vietnam War protests, exposedpolice brutality, and started the Chicanomovement for self-determination. Unfortu-nately, this organization also met with a

similar fate to that of the Black PantherParty.

AIM was organized in the summer of 1968when approximately 200 members of theNative American community met to discussvarious critical issues and developments intheir communities. These included policebrutality, slum housing, an 80% unemploy-ment rate, and racist and discriminatorygovernment policies. Today, after manylegal battles and repressive actions on thegovernments part, including the imprison-ment of leaders such as Leonard Pelletier,AIM has grown and today still continues toserve their communities from a base ofNative American culture. In Minnesota, AIMs

birthplace, organizations have developed toinstitute schools, housing and employmentservices.

In November of 1969, the world took noticewhen young Bay Area Native Americanstudents and urban Indians occupied Alca-traz Island for 19 months, claiming it asfederal land in the name of Native Nations.

In the 1960s and 1970s all of these diversegroups formed strong bonds with the BlackPanther Party. They came to understandthat we all had common problems; ourcommunities were suering from many

similar social and economic conditions. Wewere being oppressed and exploited by thesame perpetrators. These groups met withthe Black Panther Party and discussed andset forth plans to resolve some of theseissues. The Black Panther Partys 10 PointPlatform and Program was a basic plan ofaction that spelled out clearly what wewanted and what we believed. This programand platform was so powerful and so on-target that many of those solidarity groupsdrew up similar programs and tailored themto their communities needs.

Because of strong solidarity with these manydierent groups, the Black Panther Partywas able to amass great numbers of peopleto participate in demonstrations such asFree Huey, Stop the Draft, and End the Viet-nam War rallies, which occurred all over thecountry.

Included among these supportive organiza-tions were many splinter groups such as theGay Liberation Front, the Peace and Free-dom Party, the Womans Liberation Move-ment, the Yippies, the Grey Panthers andgroups that formed for the rights of disabledpeople. These solidarity groups did not gounnoticed by the FBI and were also sub-

jected to the FBIs dirty tricks and Cointelproprogram. Their oces and residences werebugged, they were inltrated by govern-

ment spies, and set-up for frame-ups andfalse arrests. Although they were harassedand brutalized, no other party, except forthe Black Panther Party, was singled out forcomplete extermination.

Many members of the Black Panther Partywere tortured, murdered, and/or lockedaway in dungeons, where many still remain,however, they did not get us all. We, thesurvivors, have a duty and a responsibility tocontinue to ght for those same 10 Points,for What We Want and What We Believe.

So, on the occasion of this Black PantherParty 40th Year Reunion and Celebration onOctober 13-15, 2006, we recognize and

invite former members of solidarity groups,especially all those rank and le members,our friends, and all those community work-ers who continue to struggle for freedomand justice to join us. We will talk about thepast, but most importantly, we will look atwhat we are doing today and explore thepossibilities of what we can accomplish inthe future. I believe we have much to do, forthe struggle does not end with us and, per-haps, by coming together in solidarity again,we can set into motion the birth of a newbeginning.

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaklshhBLACK PANTHER SOLIDARITYElbert Big Man Howard

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaldh21PANTHER LEGACY

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

22/36

-

8/6/2019 Panther Legacy Magazine

23/36

The people who have triumphed in theirown revolution should help those stillstruggling for liberation. This is our inter-nationalist duty.(Mao tse tung, Little Red Book)

Today, when I think of my experiences inthe People's Republic of China - a coun-try that overwhelmed me while I wasthere - they seem somehow distant andremote. Time erodes the immediacy ofthe trip; the memory begins to recede.But that is a common aftermath oftravel, and not too alarming. What isimportant is the eect that China and its

society had on me, and that impressionis unforgettable. While there, I achieveda psychological liberation I had neverexperienced before. It was not simplythat I felt at home in China; the reactionwas deeper than that. What I experi-enced was the sensation of freedom as ifa great weight had been lifted from mysoul and I was able to be myself, withoutdefense or pretense or the need forexplanation. I felt absolutely free for therst time in my life completely freeamong my fellow men. This experienceof freedom had a profound eect onme, because it conrmed my belief thatan oppressed people can be liberated iftheir leaders persevere in raising theirconsciousness and in struggling relent-lessly against the oppressor.

Because my trip was so brief and madeunder great pressure, there were manyplaces I was unable to visit and manyexperiences I had to forgo. Yet therewere lessons to be learned from eventhe most ordinary and commonplaceencounters: a question asked by aworker, the response of a schoolchild,the attitude of a government ocial.These slight and seemingly unimportantmoments were enlightening, and theytaught me much. For instance, the be-haviour of the police in China was arevelation to me. They are there to pro-tect and help the people, not to oppressthem. Their courtesy was genuine; nodivision or suspicion exists betweenthem and the citizens. This impressedme so much that when I returned to theUnited States and was met by the Tacti-cal Squad at the San Francisco airport(they had been called out becausenearly a thousand people came to theairport to welcome us back), it wasbrought home to me all over again that

the police in our country are an occupy-ing, repressive force. I pointed this outto a customs ocer in San Francisco, aBlack man who was armed, explainingto him that I felt intimidated seeing allthe guns around. I had just left a coun-try, I told him, where the army and thepolice are not in opposition to the peo-ple but are their servants.

I received the invitation to visit Chinashortly after my release from the PenalColony, in August, 1970. The Chinesewere interested in the Partys Marxistanalysis and wanted to discuss it with us

as well as show us the concrete applica-tion of theory in their society. I was ea-ger to go and applied for a passport inlate 1970, which was nally approved afew months later. However, 1 did notmake the trip at that time because ofBobby's and Ericka's trial in New Haven.Nonetheless, I wanted to see China verymuch, and when I learned that PresidentNixon was going to visit the People'sRepublic in February, 1972, I decided tobeat him to it. My wish was to deliver amessage to the government of the Peo-ple's Republic and the Communist Party,which would be delivered to Nixonwhen he made his visit.

I made the trip in late September, 1971,between my second and third trials,going without announcement or public-ity because I was under an indictment. Ihad only ten days to spend in China.Even though I had no travel restrictionsand had been given a passport, theCalifornia courts could have tied medown at any time because I was undercourt bail, so 1 avoided the states juris-diction by going to New York instead ofdirectly to Canada from California. Be-cause of my uncertainty about what thepower structure might do. I continuedto avoid publicity after reaching New

York, since it was not implausible thatthe authorities might place a federalhold on me, claiming illegal ight. Byying from New York to Canada I wasable to avoid federal jurisdiction, andonce in Canada I caught a plane to To-kyo. Police agents knew of my inten-tions, and they followed me all the wayright to the Chinese border. Two com-rades, Elaine Brown and Robert Bay,went with me. I have no doubt that wewere allowed to go only because thepolice believed we were not comingback. If they had known I intended to

return, they probably would have doneeverything possible to prevent the trip.The Chinese government understoodthis, and while I was in China, they of-fered me political asylum, but I toldthem I had to return, that my struggle isin the United States of America. .

Going through the immigration andcustoms services of the imperialist na-tions was the same dehumanizing ex-perience we had come to expect as partof our daily life in the United States. InCanada, Tokyo, and Hong Kong theytook everything out of our bags and

searched them completely. In Tokyo andHong Kong we were even subjected to askin search. I thought I had left thatroutine behind in the California PenalColony, but I know that the penitentiaryis only one kind of captivity within thelarger prison of a racist society. When wearrived at the free territory, where secu-rity is supposed to be so tight and every-one suspect, the comrades with the redstars on their hats asked us for our pass-ports. Seeing they were in order, theysimply bowed and asked us if the lug-gage was ours. When we said yes, theyreplied, "You have just passed customs."They did not open our bags when we

arrived or when we left.

As we crossed into China the borderguards held their automatic ries in theair as a signal of welcome and well-wishing. The Chinese truly live by theslogan "Political power grows out of thebarrel of a gun," and their behavior con-stantly reminds you of that. For the rsttime I did not feel threatened by a uni-formed person with a weapon; the sol-diers were there to protect the citizenry.

The Chinese were disappointed that wehad only ten days to spend with themand wanted us to stay longer, but I had

to be back for the start of my third trial.Still, much was accomplished in thatshort time, traveling to various parts ofthe country, visiting factories, schools,and communes. Everywhere we went,large groups of people greeted us withapplause, and we applauded them inreturn. It was beautiful. At every airportthousands of people. welcomed us,applauding, waving their Little RedBooks, and carrying signs that read WESUPPORT THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY,DOWN WITH U.S. IMPERIALISM, OR WESUPPORT THE AMERICAN PEOPLE BUT

hgfdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaklsdfj

HUEY NEWTON:

Huey Newtons auto-biography Revolutionary Suicide

CHINA IS A LIBERATED TERRITORY

fdhjhgkjkdjfkdmnviorgnfvkdfjkasdjfkljdsfaldh23PANTHER LEGACY

-