p53 Expression in ulcerative colitis: a longitudinal study

Transcript of p53 Expression in ulcerative colitis: a longitudinal study

Gut 1995; 37: 802-804

p53 Expression in ulcerative colitis: a longitudinalstudy

M Ilyas, I C Talbot

Abstractp53 Mutation is a late event in thedevelopment of sporadic colorectalcarcinoma (CRC). The timing of p53mutations in the development of ulcera-tive colitis associated colorectal carci-noma (UCACRC) is, however, less certainand some reports suggest that it may be arelatively early event. This study sought toestablish the timing of p53 mutations inneoplasia arising in ulcerative colitis.Blocks of 10 resected colorectal specimensfrom patients who had had a biopsypositive for dysplasia at least one yearprior to resection were retrieved fromthe archives of St Mark's Hospital.Immunochemistry using the monoclonalantibody DO-7, specific for both mutantand wild type p53, was performed onsections from both the resection speci-mens and dysplastic biopsy specimens.Seven of the 10 resection specimens werepositive for p53. Two of these seven speci-mens showed p53 overexpression inspecimens taken two years before thedevelopment of carcinoma or high gradedysplasia. Five of the seven specimenswere negative for p53 overexpressionbetween one and four years prior toresection. These results suggest that p53overexpression is usually a late event inthe development ofUCACRCs.(Gut 1995; 37: 802-804)

Keywords: p53, dysplasia-carcinoma sequence,UCACRC.

Colorectal CancerUnit and PathologyDepartment, ImperialCancer ResearchFund, St Mark'sHospital, NorthwickPark, Harrow,MiddlesexM IlyasI C Talbot

Correspondence to:Dr M Ilyas, ColorectalCancer Unit, ImperialCancer Research Fund,St Mark's Hospital,Northwick Park, WatfordRoad, Harrow, MiddlesexHA1 3UJ.Accepted for rapidpublication24 July 1995

p53 Is a DNA binding protein that participatesin both DNA repair and induction ofapoptosis. 1 2 Mutation of the p53 gene is prob-ably the single most common mutation foundin malignant tumours in humans.3 This muta-tion is generally deemed a late event in mostcarcinogenetic pathways. It occurs as one ofthe final steps in the adenoma-carcinomasequence in sporadic colorectal carcinoma(CRC)4 5 and participates in high grade trans-formation in malignant lymphomas.6 In ulcer-ative colitis the picture is rather less clear. Mostreports show that it is found far more fre-quently in high grade dysplasia than low gradedysplasia suggesting that p53 mutation is a lateevent.7-10 Some reports, however, suggest thatit may be a relatively early event11 and in one

report mutations have been detected in up to30% of biopsy specimens from non-dysplasticepithelium.12 Another report from the same

group has shown loss of heterozygosity, an

event that usually occurs later than mutation,

in specimens negative and indefinite for dys-plasia.8 We aimed to identify the timing of p53mutations in a longitudinal retrospectivestudy.

Selection criteriaSpecimens were selected from a series pre-viously described in a study by Connell et al inwhich all samples positive for dysplasia werereviewed.13 From those patients in which thespecimens were still positive for dysplasia afterreview, inclusion into this study was acceptedonly if at least 12 months had elapsed betweenthe dysplastic biopsy and the resection of thebowel. After application of these criteria only10 cases were found to be suitable.

ImmunohistochemistryStandard immunohistochemistry was per-formed by the ABC method using a VectastainABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Fresh 4 Kmthick sections were cut from the dysplasticspecimens and sites anatomically correspond-ing with these samples in the resection speci-men. In addition any other interesting sitesfrom the specimens were also examined.Sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydratedthrough graded alcohols. Endogenous peroxi-dase activity was blocked by incubating for20 minutes in 0 5% hydrogen peroxide inmethanol. Antigen retrieval was by boiling thesections for two minutes in an aluminium pres-sure cooker at 15 psi in sodium citrate buffer(0.01 M, pH 6.0). After preincubating for 30minutes in normal horse serum, sections wereincubated overnight at room temperature withthe mouse monoclonal antibody DO-7(Novocastra) at a dilution of 1:100. This anti-body recognises a fixation resistant epitope ofboth mutant and wild type p53. Bound anti-body was detected using the Vectastain ABCkit in accordance with the manufacturer'sinstructions with diaminobenzidine (Sigma) asthe chromogen. Sections were then counter-stained with haematoxylin and reviewed blind.Epithelial staining was scored in a semi-quantitative manner using the followingscale: 0=<10% positive cells; + =10-25%;++=25-50%; +++=>50%.

ResultsThe Table shows the results of the positivecases. Only sections in which over 10% ofepithelial cells showed clear staining wereregarded as positive. In some areas there waspale background staining of normal epithelialnuclei. Nuclei were only counted as positive if

802

p53 in UC

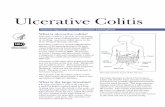

Results of the p53 immunostaining of the dysplastic biopsyand resection specimens from the seven specimens that werepositive for p53 in the resection. 0=<10% positive cells;+=10-25%; ++=25-50%; +++=>50%

Biopsy Resection Time: biopsyCase p53 (histology) p53 (outcome) to resection (y)

1 0 (LGD) + (HGD) 22 ++ (LGD) +++(Ca) 23 ++ (HGD) ++ (HGD) 24 0 (LGD) + (LGD) 45 0 (LGD) ++(Ca) 16 0 (HGD) + + (HGD) 17 0 (HGD) +++ (Ca) 2

LGD=low grade dysplasia, HGD=high grade dysplasia,Ca=cancer.

both pathologists agreed that there was signifi-cantly greater staining than that seen in thebackground. From the 10 cases, seven werepositive for p53 staining in the mucosa of theresection specimen. Of these seven, two werepositive for p53 in the earlier dysplastic biopsyspecimens (Figs 1 and 2). In both of thesecases the specimens were taken two years priorto resection. One of these patients developed amucinous carcinoma while the other showedhigh grade dysplasia in the resection. The

remaining five p53 positive specimens showedno evidence of p53 overexpression in thespecimens and there was no patient in whomthe biopsy result was positive but the resectionspecimen was negative. These results showthat p53 overexpression can occur in low gradedysplasia at least two years prior to malignanttransformation or development of high gradedysplasia. In most cases, however, the over-expression of p53 was a late event.

DiscussionThe increased risk of development of CRCin ulcerative colitis is well reported. As ulcera-tive colitis associated colorectal carcinomas(UCACRCs) often arise from flat mucosashowing cellular atypia without the polypoidarchitectural changes seen in adenomas,these tumours provide an alternative model forthe study of carcinogenesis - that is, a'dysplasia-carcinoma' sequence in contradis-tinction to the 'adenoma-carcinoma'sequence. Similar genetic changes have beenseen in UCACRCs as in sporadic CRCs and

a n .§'7@4I

FrXlW" _̂-ki'tbA-

p . --a. m..'4

Is,

A'

* -

.

..',,B '.m.js,

Figure 1: p53 Staining and a haematoxylin and eosinsection from case 3. Strong nuclear staining with themonoclonal antibody DO-7 in areas of high gradedysplasia in both the biopsy (A) and resection specimen(B). Haematoxylin and eosin section of high gradedysplasia from the resection specimen (C). (Magnification:(A) = X 562; (B) =X 288; (C) =X 144.)

Figure 2: p53 Staining and a haematoxylin and eosinsection from case 2. Strong nuclear staining with themonoclonal antibody DO 7 in areas of low gjrade dysplasiain the biopsy (A) and mucinous carcinoma in the resectionspecimen (B). Haematoxylin and eosin section of thebiopsy specimen showing low grade dysplasia (C).(Magnification: (A) = X,450 (B) =X225 (C) X36.)

803

...

2,M-Wc

804 Ilyas, Talbot

the putative 'dysplasia-carcinoma' pathwaymay share many features with the 'adenoma-carcinoma' pathway.Most p53 studies in ulcerative colitis have

shown that the frequency of immunohisto-chemical overexpression and point mutationincreases with the severity of dysplasia and thissuggests that it is probably a late event.7-10 Ouraim was to investigate this further in a longitu-dinal study in which early biopsy specimensshowing unequivocal dysplasia were investi-gated for p53 overexpression. Our selectioncriteria required that there be at least a 12month interval between the biopsy and theresection. Only 10 cases fitted our criteria and,of these, seven were p53 positive. Two of theseseven cases showed p53 overexpression twoyears prior to resection while the remaining fiveshowed no such early overexpression. Ourfindings are significant in that they show thatp53 overexpression is probably a late event inthe development of UCACRCs and are inagreement with other studies. In this respect,the carcinogenetic pathway in UCACRCs isprobably similar to that of sporadic CRCs.One important function ofp53 lies in its role

in the induction of apoptosis.2 The reductionin the ability to undergo apoptosis may lead toimmortalisation of cells. This would tend toincrease the accrual of mutations, which mayeventually be sufficient for malignant transfor-mation (as in the Epstein-Barr virus inducedimmortalisation of lymphocytes).14 15 In such amodel the loss of ability to undergo apoptosis isan early event. Alternatively, if the 'transform-ing' mutations have already occurred then lossof ability to undergo apoptosis will allow theseordinarily lethal mutations to survive. In thismodel loss of apoptosis inducing processesoccurs as a late event. Our findings suggestthat p53 is a late mutation in the developmentof UCACRCs and suggest that, in terms ofdisease biology, loss of apoptosis may be a lateevent.

This study is, however, limited by too fewcases to draw any important conclusions.None the less, only in a truly longitudinal studysuch as this can the natural history of a diseasebe followed. Another limitation is the use ofimmunohistochemical overexpression as anindication of probable mutation. We may thushave missed some non-sense mutations result-ing in truncated protein. In addition, given thehigh degree of sensitivity of antigen retrievalmethods, we may have detected overexpres-sion of wild type protein - that is, appropriate

expression of non-mutant p53 - in an attemptto induce apoptosis in neoplastic cells.Unequivocal overexpression of p53 protein inover 5% of tumour cells has been shown tobe very highly correlated with p53 pointmutations in colorectal carcinomas.16 We setrigid criteria for the definition of positivestaining to prevent false positive results - onlywhen both pathologists were in agreementwere cells accepted as positive. For complete-ness, however, direct genetic analysis of thep53 gene in these cases is required.

In summary, we conducted a longitudinalstudy in an attempt to identify the timing ofp53 mutations in ulcerative colitis. Our resultssuggest that this is probably a late event inthe 'dysplasia-carcinoma' pathway. In this weare in agreement with other workers and thissuggests that a 'dysplasia-carcinoma' sequencehas some features in common with the'adenoma-carcinoma' sequence.

1 Lane DP. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature1992; 358: 15-6.

2 Hinds PW, Weinberg RA. Tumor suppressor genes.Curr Opin Genet Dev 1994; 4: 135-41.

3 Hall PA, Lane DP. p53 in tumour pathology: can we trustimmunohistochemistry? - Revisited! J Pathol 1994; 172:1-4.

4 Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectaltumorigenesis. Cell 1990; 61: 759-67.

5 Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, Paraskeva C,Markowitz S, Wilson JK, et al. p53 Gene mutations occurin combination with 17p allelic deletions as late events incolorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 1990; 50: 7717-22.

6 Sander CA, Yano T, Clark HM, Harris C, Longo DL, JaffeES, et al. p53 Mutation is associated with progression infollicular lymphomas. Blood 1994; 82: 1994-2004.

7 Harpaz N, Peck AL, Yin J, Fiel I, Hontanosas M, Tong TR,et al. p53 protein expression in ulcerative colitis-associatedcolorectal dysplasia and carcinoma. Hum Pathol 1994; 25:1069-74.

8 Burmer GC, Rabinovitch PS, Haggitt RC, Crispin DA,Brentnall TA, Kolli VR, et al. Neoplastic progression inulcerative colitis: histology, DNA content, and loss of ap53 allele. Gastroenterology 1992; 103: 1602-10.

9 Chaubert P, Benhattar J, Saraga E, Costa J. K-ras mutationsand p53 alterations in neoplastic and nonneoplasticlesions associated with longstanding ulcerative colitis.AmJr Physiol 1994; 144: 767-75.

10 Taylor HW, Boyle M, Smith SC, Bustin S, Williams NS.Expression of p53 in colorectal cancer and dysplasiacomplicating ulcerative colitis. BrJ Surg 1993; 80: 442-4.

11 Yin J, Harpaz N, Tong Y, Huang Y, Laurin J, GreenwaldBD, et al. p53 Point mutations in dysplastic and cancerousulcerative colitis lesions. Gastroenterology 1993; 104:1633-9.

12 Brentnall TA, Crispin DA, Rabinovitch PS, Haggitt RC,Rubin CE, Stevens AC, et al. Mutations in the p53 gene:an early marker of neoplastic progression in ulcerativecolitis. Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 369-78.

13 Connell WR, Lennard-Jones JE, Williams CB, Talbot IC,Price AB, Wilkinson KH. Factors affecting the outcomeof endoscopic surveillance for cancer in ulcerative colitis.Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 934-44.

14 Epstein AM, Achong BG. The Epstein Barr virus. Berlin:Springer, 1979.

15 Niedobitek G, Herbst H. Epstein-Barr virus-associatedcarcinomas. EBVReport 1994; 1: 81-5.

16 Costa A, Marasca R, Valentinis B, Savarino M, Faranda A,Silvestrini R, et al. p53 gene point mutations in relation top53 nuclear protein accumulation in colorectal cancer.JPathol 1995; 176: 45-53.