ORPHEUS LOST - HarperCollinsstatic.harpercollins.com/harperimages/ommoverride/Orpheus Lost... ·...

Transcript of ORPHEUS LOST - HarperCollinsstatic.harpercollins.com/harperimages/ommoverride/Orpheus Lost... ·...

HarperCollinsPublishers Teaching Notes

on

ORPHEUS LOSTby Janette Turner Hospital

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 1

Fourth EstateAn imprint HarperCollinsPublishers Australia

These teachers’ notes are not to be sold

Prepared for HarperCollinsPublishersby John Allen. Typeset by Helen Beard, ECJ Australia Pty Limited

Orpheus Lostfirst published in Australia in 2007by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty LimitedABN 36 009 913 517www.harpercollins.com.au

Orpheus Lost © Janette Turner Hospital 2007

HarperCollinsPublishers25 Ryde Road, Pymble, Sydney, NSW 2073, Australia31 View Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 2

Contents

Orpheus Lost . . . • 5

Structure • 8

The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice • 9

Themes • 11

Characters • 14

Style of Writing • 17

About the Author • 18

Questions for Discussion • 19

Essay Topics • 21

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 3

Orpheus Lost . . .

Orpheus Lost is a rich and complex story exploring what drives

people to behave the way they do, as they search to give meaning to

their lives. Janette Turner Hospital examines the comfort of living in

the privacy and security of one’s isolated world, yet with the

realisation that such ‘cocoons’ are illusory once we acknowledge our

connection with other people, especially those we love.

Taking on a theme that has continued to preoccupy writers – not

least of all William Shakespeare – the novelist is fascinated by the way

people are rarely what they seem. Indeed, it is only when the

characters come to know one another that they arrive at a glimmer of

understanding of what drives them, even when the persons themselves

are unsure as to the reason for their preoccupation. Turner Hospital

lets us know how, under these circumstances, people can change

remarkably for the better or the worse.

Primarily, the author is concerned with the redemptive quality and

the pain of loving in a world where, so often, power in the hands of

both institutions and individuals comes to be a brutal force of

destruction, not least of all the terrifying power of religious fanaticism

and political activity for which no one will take responsibility.

Orpheus Lost maps the youth and early childhood of three

characters: the Orpheus figure, Mishka Bartok (aka Mikael Abukir);

his Eurydice, Leela Moore; and her childhood friend, and the couple’s

nemesis, Cobb Slaughter. Mesmerised by the power of Mishka’s violin

playing in a Boston underground station, Leela falls in love with the

5

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 5

Jewish Australian. He is completing advanced studies in music at

Harvard; she, a post-doctorate in mathematical equations pertaining

to musical composition, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

(MIT). Cobb, a retired officer with the Unites States army, now

working as an independent military advisor, is involved in the

surveillance of Mishka, who is associating with a radical Islamic

group in Boston, in an attempt to make a connection with his father,

whom he thought was dead. Cobb’s ‘watching’ focuses intensely on

Leela, his ‘blood sister’, with whom he has always been obsessed and

dementedly jealous of any male she may favour ahead of him.

The novel is a fascinating study of obsession. All three characters

are driven by their passions, and experience the ecstasy and anguish

that result from such drive, for, as the sign above Leela’s desk says,

‘Obsession is its own heaven and its own hell.’ Suicide bombers attack

American cities. Radical Islam devotees pronounce their own manic

vision of the world while Leela’s father lives in the little town of

Promised Land, Southern Carolina, where his repair business is titled

‘Sword of the Lord and of Gideon’, and he attends the ‘Church

Triumphant of Tongues of Fire’! Cobb’s alcoholic father still

acknowledges the Confederate flag that continues to be flown in

Charleston, and, wracked by brutal memories of his service in

Vietnam, pours vitriol upon the world. Thus, the characters are not

‘normal’, in the sense that they do not accord with the usual

parameters of society: each is driven, in one way or another, by their

predicament, and each is immeasurarably human. They have to make

decisions and live with the consequences of their actions – and all of

this takes place in a riveting tale, exploring moral dilemmas in a world

of pain and loss.

Critic Peter Craven writes of the novel that Turner Hospital ‘bridges

the gap between highbrow and popular fiction’, commenting that ‘she

is writing literary fiction that has the readability and the page-turning

6

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 6

suspense normally associated with popular or trash writing’. Her

notable literary qualities lie in the intriguing structure of the text and

the sophisticated point of view from which that story is told; the

richness of the character delineation and the mythic sub-strata of the

tale; the complex moral issues the text explores, and the superb

command of language that appears to be so effortlessly employed.

7

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 7

Structure

From the opening sentence, ‘Afterwards, Leela realized, everything

could have been predicted from the beginning,’ the retrospective

nature of the narration is apparent. The story is told by shifting back

and forth between past and present, and the significance of the past to

the present situation is revealed. At the end of the novel, Leela’s future

actions are suggested: ‘She knew she would…’ Each title of the nine

chapters, or books, as they are called, is the name of one of the three

main characters; the home town of Leela and Cobb, Promised Land;

or other dimensions, Underworld and Unheard Music.

While the point of view remains omniscient, so that the characters

and their world are seen from a God-given perspective, the personal

focus of each book allows the reader to gain an intimate perspective

of each of the characters’ thoughts and feelings. Much of this results

from subtle shifts in tone. One can compare the perspective of Leela

in Book I, which is personal, passionate and questioning, to that of

Cobb in Book II, where the tone is cold, clinical and objective –

‘Slaughter had the woman taken directly to the interview room.’

Such a kaleidoscopic point of view and complex structure are in no

way a burden, as the narrative unity is never lost, and the reader is

drawn into the lives of these complex and fascinating characters.

8

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 8

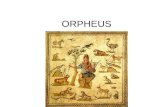

The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice

Turner Hospital’s novel is a re-imagining of the myth of Orpheus and

Eurydice. Orpheus was the sweetest singer and most accomplished

musician the world had ever seen. His lyre, said the ancient Greeks,

was presented by Apollo himself. When he played and sang, wild

animals gathered and even trees swayed in harmony. When his bride,

Eurydice, is bitten by an adder and goes to the land of the dead,

Orpheus can not be consoled. Taking his lyre, he follows her spirit. In

the underworld, he begs Hades and Persephone to restore his wife to

him and to the sweet sunshine. Charmed by his music, they agree, but

one condition is laid down: on their way up from the valley of the

dead, neither Orpheus nor Eurydice is to look back. Up and up

through the darkened ways they go, Orpheus leading, never looking

behind. As they near the place where the land of light and living opens

up, a white-winged bird flies by, and Orpheus turns in ecstasy to

Eurydice, exclaiming, ‘O, Eurydice, look upon the world I have

returned you to.’ As he speaks, he turns to Eurydice, and, in that

instant, she slips back into the darkest depths of the valley. All he

hears is one word, ‘Farewell.’

Not only is Mishka called Orpheus for much of the text, his

personality and actions parallel that of the mythic character. His lyre

is the heritage of the revered Uncle Otto; the animals he charms may

not be wild, but the travellers in the Boston underground are

mesmerised by the young man’s music. Then the myth is subverted; the

identities are reversed. It is not Eurydice but Orpheus who is bitten by

9

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 9

the fang of international terrorism, brutal interrogation and torture.

While Orpheus’s music had charmed Cerberus at the gates of Hades,

on this occasion, Mishka’s music brings nothing other than scorn.

Nevertheless, the devoted female follows the spirit of her lover

through dream, psychic connection and determined action. The novel

concludes with a positive vision. The battered Orpheus is not left to

eternal darkness, but is eventually freed by Cobb, to return to the

sanctuary of the Daintree and the love of his Eurydice.

10

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 10

Themes

Finding Sanctuary

Most people wish to feel safe and secure in their world, and create

microcosms so that they can peacefully pursue their interests and live

out their lives. Turner Hospital suggests that such ‘cocoons’ are fragile

indeed, even illusory. Mishka lives in the ‘haunting cocoon of his

music’, but that offers little protection from brutality. Chateau

Daintree, the promised land, which represents safety, belonging and

connectedness, is a little ‘cocoon’ in which Grandpa Mordecai and

Grandma Malika are suspended, cut off from the world, yet, living

with the legacy of Hitler’s death-camps, they have to ‘unmake the past’

in order to find meaning in the world. Leela comes to realise that her

obsession with mathematics was ‘an addiction. It was my beautiful

cocoon,’ which she leaves behind as she pursues her lover. In studying

the text, one ought to consider how effectively the various characters

pursue independent interests yet still manage to function in the world.

Descent into the Underworld

Turner Hospital has stated: ‘I have always been intensely interested in

people without political agendas who get caught up in political events

and have to negotiate their way through them … That’s been the

subject of all my novels, and specifically this one.’ Set in the immediate

present, Orpheus Lost taps into public fears about terrorism, war and

11

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 11

torture in the Iraq context. Along the way, Turner Hospital probes the

secrecy surrounding ‘extraordinary rendition’, ‘ghost detainees’ and

Abu Ghraib, to examine what can happen to individuals when errors

are made in the name of national security. ‘Rendition’ is a process

whereby political prisoners are taken to countries where torture is not

illegal, in order to inflict it upon them without consequence. The term

‘ghost detainees’ refers to people who are arrested or kidnapped and

imprisoned of whom no record of arrest or imprisonment is kept. In

terms of military and prison records, these people don’t exist and

nothing was ever done to them.

Mishka’s search for his father becomes a journey spiralling out of

control, resulting in his brutal torture in Iraq. He is a victim of

rendition. Searching for her love, Leela visits Camp Noir, a detention

centre in Australia, where the ‘ghost detainee’ who is suffering from

‘post-interrogation disorder’, proves not to be Mishka. The

inhumanity of the treatment of those who are politically suspect is the

didactic focus of the novel.

Another dimension of the underground are figures such as Cobb,

ex-military personnel who carry out clandestine activities in order to

serve governments and companies, or simply pursue their own

personal vendettas. They hold frightening power in the community

and are accountable to no one.

A Sense of Place

Orpheus Lost examines the private lives of individuals – their inner

lives, the particular places in which they live – and all of this is seen

within the context of global concerns. Leela and Mishka are studying

in Boston, a diverse and complex modern city where there is tension

in Muslim–Christian relations. In the wake of 9/11, of the Bali

bombings, and the London and Madrid railway bombings, the novel

12

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 12

imagines a possible near future in America where random terrorist

attacks are occurring.

Two of the nine chapters are titled ‘Promised Land’ after that

remarkably named place in South Carolina where Leela-May

Magnolia Moore and Cobb Slaughter grew up and where their

families still reside. Promised Land seems lost in time: the Civil War

seems as though it was fought only a decade earlier and its legacy is

ever present – think of Cobb’s tattoo! A Mason-Dixon Line is still

perceived, and Leela is distrusted for going to the North. This is a

fundamentalist community, inhabited by many eccentrics, but

ultimately a place of kindness. Leela’s sister, Maggie, wants to keep

living there to serve the community. Whilst racial tensions have

lessened, the figure of Benedict Boykin, an African-American,

represents the disproportionate number of black and impoverished

Americans in the regular army fighting in the Iraq war.

Also called ‘Promised Land’, at one point, is the home of Mishka’s

grandparents in the Daintree. The focus here is less on the area than it

is on the house itself, and ‘Bartok’s Belfry’, which Mishka describes as

‘paradise’. The enchantment of Europe is transplanted to this

fabulously colourful and peaceful home, the very antitheses of the

underworld and the place of repose to which, literally and

symbolically, Mishka returns at the end of the novel for the healing to

take place.

13

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 13

Characters

Akin to Orpheus, his mythic self, Mishka is a recluse who ‘live[s]

inside [his] music’. As he declares upon first meeting Leela, ‘I listen to

music, I play music, I compose it. I don’t do anything else … I’m just

no good at anything normal’. Mishka’s creative endeavour involves

reconciling Western and Islamic culture, composing music set to the

work of Rumi, the thirteenth-century Persian mystic, and as with the

mystics, the young musician appreciates that understanding comes not

only from analytical thinking but also by attending to one’s intuitive

self and one’s dreams. He implores Leela to place her ear against his

heart so that she may hear his sonatine before he has written it down.

After his awkward initiation to primary schooling the five-year-old

seeks escape through art: ‘I do not belong on this page, he concluded.

He wanted his mother to paint him somewhere else.’ His intuitive self

is apparent when, before meeting his father, he tells Leela, ‘I have a

feeling of dread’.

Leela also comes to realise that humans co-exist in multiple

dimensions. The couple live much of their time in music and

mathematics, which, as Berg says to Leela, ‘constructs an ideal world

where everything is perfect but true’. However, she too comes to listen

to her inner self, realising that ‘dreams can mean something … that we

don’t have equations for’, as she comes to make a psychic connection

with her lover, now in a different country to her. In many ways, Leela

is the hero of the novel. Perhaps she inherited a ‘fearless gene’ from

her father. She has a ‘rapacious curiosity’, fierce determination,

14

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 14

together with an acerbic wit. Threatened by the drunken Calhoun

Slaughter, she asserts, ‘if you lay a hand on me, you know my Daddy

and the elders will come and pray for you on your own front porch.

They’ll pray the Holy Spirit down and you’ll get Jesused.’ Yet her

finest quality is her love for, and devotion to Mishka. Whilst she

certainly doesn’t understand his actions for much of the time, she

never loses faith in her lover, pursing him with hope against hope,

when, like Orpheus, he is lost in his underworld.

In many ways the most fascinating character in the novel is Cobb

Slaughter. His ‘skittish intensity’ and the ‘need for totemic power’ can

well be understood when one considers how he was beaten as a child

by his tortured father who had been given a Dishonourable Discharge

in the Vietnam war. With the death of his mother, there is no nurturing

figure in his life, but a consoling figure for him is Leela. The

youngsters come to realise that ‘they both lived in crackbrained

families; they both lived without benefit of mothers; they both

navigated, daily, around highly unpredictable dads.’ Bonded by blood,

Cobb, when separated from Leela, is like an ‘amputated limb’.

In many ways Cobb is an obnoxious character. He makes a

frightening imposition upon the privacy of others; is brutally offensive

to Leela, whom he calls ‘the slut of Promised Land’; and is sexually

kinky. Yet he comes to be the moral hero of the novel, and, as with his

crass father, he is seen to have redeeming qualities. As Leela says to

him when they are searching for Mishka, ‘you’re decent, Cobb, and

he’s innocent’. He attempts to redress the situation, recognising that

things were not as he had planned, and he searches for ‘atonement’.

Mishka’s nemesis eventually becomes his saviour, at the cost of his

own life.

While the three main figures are rich and fascinating characters, one

of the intriguing qualities of Turner Hospital’s novel is the minor

characters. Such creations are necessary to serve the plot, to move the

15

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 15

action along, but, in the hands of this writer, all are distinct individuals

with their own personalities. Indeed, the reader’s perception of these

figures can change dramatically, as is the case with Calhoun Slaughter.

Students should examine the details of the text to consider what we

learn of the following characters and how the writer brings them to

life:

Devorah Bartok

Calhoun Slaughter

Berg

Jamil Haddad

Maggie

Ali Hassan

Benedict Boylan

Mr Hajj

Marwan Abukir

Grandma Malika

Grandfather Mordecai

Gideon Moore

16

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 16

Style of Writing

It has been said that, for the writer, style should be a feather in one’s

arrow rather than a feather in one’s cap. The wonderfully evocative

prose of Turner Hospital’s novel is never simply employed for effect;

rather it is crafted to capture place, character and incident. Consider

the fusion of people and place in this description of Bartok’s Belfry:

‘Grandma Malika would light the candles, and Mishka thought of

himself and the three people he loved as figures inside a music box,

leaning toward each other over the white linen cloth. They were inside

the light, inside the golden circle, and just beyond the table, on all

sides, were the heavy drapes of rain, folds of water flashing white and

silver like roped silk.’

The descriptions of the Daintree provide moments of transcendent

beauty for Mishka:

‘His grandfather drove him down when the morning lay like gold

leaf on ocean and on cane fields and on the steep forested slopes. Last

night’s rain was always steaming up from the road so that Mishka saw

hundreds of wraith-cobras performing for the snake-charmer sun.’

Consider also the way in which the writer employs a mythic

dimension throughout the tale. In ‘searching for nuggets of his father’

Mishka ‘could not speak of the precious but ominous thing he had

found: his father’s existence. It was like one of those double-edged

treasures in Scheherazade’s tales: a jewel that brings death to the

finder’. Consider the prescience of that image within the context of the

novel.

17

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 17

About the Author

Janette Turner Hospital was born in Melbourne in 1942, but grew up

in Brisbane and then began her teaching career in northern

Queensland. She completed her post-graduate studies in Canada and

has lived in India, England, France and the USA, where she currently

holds the endowed chair as Carolina Distinguished Professor of

Literature at the University of South Carolina.

Her first novel, The Ivory Swing, was published when she was forty,

and won Canada’s Seal Award. The Last Magician, her fifth novel,

was listed by Publishers Weekly as one of the twelve best novels

published in the US in 1992, and was a New York Times Notable

Book of the Year, as was Oyster, her sixth novel. Due Preparations for

the Plague won the Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2003, the

Davitt Award for best crime novel of the year by an Australian

woman, and was shortlisted for the Christina Stead Prize in the 2000

NSW Premier’s Literary Awards.

In 2003 Janette Turner Hospital received the Patrick White Award

for lifetime literary achievement.

Her inspiration for Orpheus Lost came whilst standing on the

subway station in Harvard Square, listening to buskers from the

nearby Julliard and Harvard schools of music. She became so

enamoured of the music that she missed trains, ‘listening to this

glorious music in the bowels of the earth.’ For all this, Orpheus Lost

remains an intensely political novel.

18

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 18

Questions for Discussion

1. The impact of religion is obvious throughout the novel:

Leela’s family’s fundamentalism; Islam; Berg’s Judaism; the

Diaspora and the Bartoks.

What is Turner Hospital’s final verdict on religion? Does shemake any judgments? To what extent does the novel suggestthat redemption will be found other than in religion, i.e.through the intensity of one’s love?

2. The author’s interconnected narrative does require energy

to follow the plot.

Does such a structure enhance or inhibit the novel’s progress?

3. Through the media, readers have been extensively exposed

to news stories about turmoil and terrorism.

To what extent is Turner Hospital’s novel different?

4. ‘Leela is self-centred, impulsive, rebellious; Maggie, her

sister, is a much more pleasant person.’

Do you agree with the above judgment? Can Leela beconsidered the ‘hero’ of the novel?

19

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 19

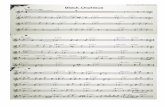

5. Music in all its forms is seen as the dominant leit motif of

the novel: the violin and the Persian oud; Uncle Otto; the

two universities; the epigraph itself.

Discuss the importance of music in the novel.

6. In what ways do the Slaughters – Calhoun and Cobb –

come to mirror one another?

Consider your initial impressions of both men, and how andwhy they change.

7. Turner Hospital has stated that she was always interested

in people without any political agenda who get caught up

in political events.

In Orpheus Lost, how do the characters manage to cope withthis experience?

20

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 20

Essay Topics

1. In what way is the text structured to engage the reader’s

curiosity and present the story in an engaging manner?

2. ‘Turner Hospital’s characters are flawed individuals, but

ultimately good.’

Do you agree?

3. ‘Despite the black horror of the subject matter, the novel is not

pessimistic.’

Do you agree?

4. ‘Ultimately, the true hero of the novel is Cobb Slaughter.’

Do you agree?

5. ‘Sport of the gods,’ Mishka Bartok said. ‘That’s what we are.’

Does Turner Hospital’s novel endorse this point of view?

21

Teaching Notes - Orpheus Lost 27/9/07 1:33 PM Page 21