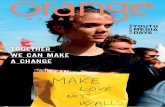

Orange Magazine 2013

-

Upload

deutsche-welle -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Orange Magazine 2013

Where the economy meets the media

2

MAGAZINEEDITORIAL

Where are the

economic values?

The raid-like closure of the Greek state broadcaster ERT caused a wave of outrage in Athens and surrounding Europe: getting rid of mass media this way should be, democratically speaking, an abso-lute no-go and is actually unworthy of a developed European state. The topic of this year´s Global Media Forum, ‘The future of growth – Economic Values and the media’ emphasises these issues. Our economic system has little to do with solidarity and social fairness. Instead, it’s all about growth. Or at least that is what media is lead to �������Ǥ� �������ǡ��������������������������������Ƥ������ Ǯ����������ǯǣ�an economic and political system controlled by corporations or cor-porate interests.

As DW Director General Erik Bettermann said in his keynote speech on Monday, the international community is facing pressing chal-lenges: among them international tensions, rising energy prices and

Editorial: Armand Feka, Austria

�����������Ƥ��������������Ǥ����������ǡ��������ǡ����������������������-bility to deal with the consequences of these developments.

We see old national stereotypes quickly re-emerging. Interest rates, spreads and the almighty markets dominate everyday life. We have ��������������������Ƥ��������������ǡ������������������������������(“the markets reacted in an unsuspected way”). But the markets are merely unkind and juvenile Greek gods, punishing those they do not consider worthy of their power.

If participants took just one message from Noam Chomsky’s speech it was that the old cheques and balances have been disabled and new, less democratic economic values are dominating the current economical Zeitgeist.

3

CONTENTS

4 | PINEAPPLE: The profitable industry that damages communitiesTen years ago, Xinia Briceño received the alert that the water in her community was polluted. Studies proved that it had residues of agrochemicals.

8 | MICROFINANCE���������Ƥ������������������������ ����� ǯ����������������������������������������������ǯ������Ǣ���������������������������������������������������������Ƥ�������������the one that needs saving.

10 | YOUTH EMPLOYMENT Youth unemployment is at an all time high globally; in Kenya the latest statistics stand at � ��������Ǥ��������������������������������������������������Ǧ���������������������� change the tide.

18 | EGYPT: When joblessness hits hardDuring the January 25th revolution, Egyptian youth demanded solving the unemployment problem, putting an end to nepotism and setting minimum and maximum wage rates.

23 | PALESTINEMa‘an is the most important news agency in Palestine. Raed Ohtman, its founder, says the key to its success has been to be the voice of those who can’t speak.

26 | PEACE

27 | GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

EUROPEAN YOUTH PRESSEuropean Youth Press is an umbrella association of young journalists in Europe. It involves more ����� ǡ� ������������ �������� ���� �����������magazines, Internet projects, radio and video productions, or are interns in newsrooms, freelance journalists, journalism students or trainees. With print magazines or blogs, podcasts and v-casts, the association wants to give young media makers from all over Europe the opportunity to cooperate directly with each other. Above all, the aim of all member associations and the umbrella structure is to inspire young people to deal with media and take an active part in society by fostering objective and independent journalism.

ORANGE MAGAZINEFresh. Vibrant. Creative. Orange Magazine provides journalistic education and supports young journalists by giving them room to explore media ���� �������� �ơ����Ǥ� �������� ���� ���������������������ơ������ �����������������������������������make this magazine unique. They create multi-faceted magazines with new and interesting content. Creating it means having an exciting time in an ever-changing environment. Reading it means getting facts and opinions directly from young and innovative journalists.

POWERED BY

IMPRINT

Orange Magazine European Youth Press,����������������ǡ����������ǡ��������

Editors in ChiefDobriyana Tropankeva (Dinamark)Armand Feka (Austria)

Photos bySuy Heimkhemra (Cambodia)Biayna Mahari (Armenia)Michele Lapini (Italy)

Layout byPetri Vanhanen (Finland)Bruna Pickert (Brazil)

Proofread byEmanuela Campanella (Canada)Vanessa Ellingham (New Zealand)

ContributorsFisayo Soyombo (Nigeria)Nina Lex (Canada)Nadya Priscilya Hutajulu (Indonesia)Camila Salazar (Costa Rica)Sebastián Rivas (Santiago)Akanksha Saxena (India)Sarah El Masry (Egypt)

���������������������� ���������������������������������Ǧ���������������������������Ǥ�Does a country’s economic growth lead to peace for its people?

Dz��������������������ǡ����������������������������Ǥ��������������������������������Ǥdz�Ǧ�Aart de Geus, Chairman of Bertelsmann Stiftung.

4

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

Ten years ago, Xinia Briceño received the alert that the water in her community was polluted.

Studies proved that it had residues of agrochemicals. This was almost six years ago. Now a

truck has to come twice a week to the village to provide drinking water to its residents.

Xinia Briceño lives in Milano, Limón one of the several communities in Costa Rica, where the pineapple industry has settled in. This tropical fruit is currently the country’s leading export crop. Just ��� ǡ� ���������� �������� ������������ ������ ��� Ǥ� �������ǡ� ά� ��� ����product goes to Europe. Even if Costa Rica has grown pineapple for the foreign markets since the sixties, over the last ten years the activity has risen exponentially. ���� ������������ ����� ����� ����� Ǥ���������� ��� � ��� Ǥ� ��� ǡ�according to the Ministry of Agriculture.

BITTER TASTEAccording to the National Chamber of Pineapple Producers (CANAPEP), besides the revenues, the pineapple industry gives to ������������Ǥ������������Ǥ��������������ǡ�this phenomenon has also lead to negative consequences for communities next to plantations and for workers.

To export the fruit, the enterprises have ��� ���Ƥ��� �������� ������ ������������� ������������������ �����Ƥ�������ǡ� ����� ���������������������� Ǥ����������������that the product has certain standards. However, the companies are not obliged to have a mitigation plan for the social and environmental impacts. At the same time, the ministries of Agriculture, Environment and

Health are in charge of technical supervision of plantations, but a lack of personnel hinders �������Ƥ�������������������������Ǥ�

As a result, problems such as water and soil pollution, erosion, sedimentation and deforestation, have arisen. For example, the community of El Cairo, in Limón, has had to collect their drinking water from a ������� ������ ǡ� ������ ������ ����� ��� ����Costa Rican Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers (AyA), that determined the water had traces of the agrochemical Bromacil (used ��� ���������� ����������Ȍǡ� Ǥ� �����������per litter, which is way above the quantity ���������������������������������ǤǤ��

by Camila Salazar, Costa Rica

Pineapple: tJG� RTQƇVCDNG� KPFWUVT[�VJCV�FCOCIGU�EQOOWPKVKGU

<<

Young media entrepreneurs are reshaping the way content in the media is created and delivered in Chile.

Photo: Camila Salazar

5

fEATuRE

Dz������ ���� ����� ǡ� ����� ���� ����������plantations were installed in our community, people’s health have deteriorated. Since then, people began reporting breathing problems, skin diseases and cancer”, said Erlinda Quesada, a community leader in Guácimo, Limón. Due to the expansion of big plantations, some local farmers are incapable of competing, so most of the time they decide to sell their lands to big enterprises. Most of the workers are men between the ages �������ǡ������������ά����������������immigrants, especially in the north of the country, and the Caribbean coast. Didier Leitón, member of the Union of Plantation Workers (Sitrap in Spanish), explained that depending on the plantation, the working time can go from eight to sixteen hours a day, and average salaries are below the minimum ����ǡ���������������������������Ǥ��

To avoid the payment of social security charges, some companies subcontract enterprises to hire workers. They make temporary contracts for two or three months, so that they can

���� �ơ� �������� �������� ��������� ���������Ǥ��This also reduces the company’s direct responsibility to provide adequate working conditions. Despite these situations, most of the workers have no choice, considering that pineapple or banana plantations are the only sources of employment.

WHAT TO DO?Since Europe is the main market for Costa Rica’s pineapple, some organizations, such as Consumers International, have tried to raise awareness of the situation in this tropical Central American country.��� ���������ǡ� �������� ���� �����Ƥ��������such as Fairtrade, is a way to ensure that the pineapple comes from a plantation with good social and environmental practices. Also, some communities have found shelter in environmental organizations that help �����Ƥ���� ���� ������ ������Ǥ� ����� ����������of Guácimo, for example, after struggling for several months, managed to make the local authorities adopt a moratorium on the cultivation of pineapple in the southern part

of the region, were previous plantations had polluted the water.

The alternative for Erlinda Quesada, the community leader in Guácimo, is simple: “Instead of pineapple plantations, we need support from the local government to invest in rural tourism, and give more credit facilities to local entrepreneurs”.

This solution is possible. For example, a few kilometers from Guácimo several families united to create the Association of farms for the development of rural community tourism (AFITURA). The idea was to provide locals an alternative for sustainable development.

If the plantations continue to grow without regulations and social responsibilities, Xinia Briceño and her family will continue to receive water from a truck. For them the drinkable liquid will just be a memory once shattered by a fruit that came to the community without invitation.

“ „after the pineapple plantations were installed in our community, people began reporting breathing problems, skin diseases and cancerErlinda Quesada, a community leader

<< Pineapple is mostly cultiveted in the Caribean and Northen regions of Costa Rica. Photo: Camila Salazar

6

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

by Sebastián Rivas, Chile

6GNN�OG�UQOGVJKPI newYoung media entrepreneurs are reshaping the way content in the media is created and

delivered in Chile. They are new faces that are unafraid to criticizethe current system

and voices of a generation that is changing the way people consume information.

“Here begins DemasiadoTarde”. Every night, NicolásCopano opens his program in Santiago, Chilewith the samecatchphrase. ����� � ������ ���ǡ� ��� ��� ���� ������ ����� ���prestigious late night showDemasiadoTarde

(Too Late) partnering with Google and CNN. But their live show is not broadcasted on any TV channel, you can only watch it online.

Copano leads a group of young journalists who are changing the rules of the game in the Chilean media. His production company ��� ����� ��� ���� ��� ����� Ƥ��� ���������� ���YouTube for Latin America and he has

anchored streaming broadcast events such as Lollapalooza Chile –the Chilean version of one of the most important music festivals in ���������Ǥ�����������ơ�������������������and traditional journalists is that he actually ����� ���� ����Ǥ� Dz�� �������� ����� ��� Ƥ��� ������ago that I could be a media partner and not an employee,” Copano says.

>>31 Minutos is a kids show presented by puppets. Two of them are Tulio Trivinõ (left) and Juanin. Photo: APLAPLAC

7

fEATuRE

DemasiadoTarde has a business model which has been very successfulup to now. Its main revenues are from advertising: Copano explains that the companies pay almost the same than in TV: in prime time, for example, one single commercial could cost almost Ǥ� ���� � ������Ǥ����� ��ơ������� ��� �����the companies enjoy advertising not only in the show, but also in social media like Twitter and Facebook.

��������������ƪ�������������������������������� ��������������Ǥ� ��� ǡ� ���� �������� ����������� ��� ���� �������� ��������� ��� � ������of democracy: hundreds of thousands of students questioned the economic and social development of the state.Copano took the role of spokesman of a new platform. “Our average viewer age is only 22 years,” he says. The same age ashis team, with most of them beingyoung students.His show is seen live ��� ǡ� ����� ������ �����Ǥ� ���� ��� ����� ����������������������������������������������to reaching your comments and the highlights of each program. “We are the only Latin American internetstartup channel. For us, the main focus is online”, he says.

WORKING WITH NEW IDEASA decade before Copano, another group of young people followed a similar path. Alvaro Diaz, Pedro Peirano and Juan Manuel Egaña

�������� ����������� ǡ� �� �����������company with the idea of creating content for TV.Their ideas were promoted too risky for �����������������Ǥ����ǡ�����������������children’s news program hosted by puppets, but with strong irony and addressing issues considered adult: allegations of damage to the environment, human rights and social criticism to a market-oriented system. ”Children watched a lot of TV, therefore already seeing news.” The proposal was not accepted by the channel. However, they won a millionaire fund awarded by National Television Council, a state institution focused on supporting new projects that allowed the production and broadcasting of the show.

�������������ǡ����������������ȋ��������Ȍǡ�soon became an unexpected success. Not only for its ratings, but because it became a symbol of a generation of children. It had one of the most viewed Internet pages of the country at a time when it was unusual for programs to have an online presence. The soundtrack of the series became the best selling album of Chile of the last decade.The program was sold to Nickelodeon channels and other countries such as Mexico, Uruguay, Colombia and ������Ǥ����� ����� ���� �� Ƥ��� ������������ �������������������� ǡ�������������� �������ǡ�the biggest budget for a Chilean movie at that moment.Last year, the children’s program

was presented at the Festival de Vina del Mar, Chile’s most prestigious event. It achieved ������������������������������ǣ�ά������������in the country saw the show. “Originality is fundamental, if you don’t have a dynamic trial and error system, you will succumb to the very Ƥ�����������dzǡ����������Ǥ

ORIGINALITY TO CHANGE�����������������������������������������believe that in an atmosphere of change in the Chilean media, young voices have much more space to contribute. “Our audience is born after the Pinochet dictatorship. It is a generation unafraid to say its opinion. It’s like the public of Egypt, Syria and Libya: a new voice”, Copano says. Diaz believes that taking a stand is a factor that cannot be absent in the new media:”Neutrality is a bad idea. If humanity and programs have special features, they become more attractive”.

But the greatest contribution of this new generation is the diversity of ideas they bring and the quest for a brand new model of media. “The new audience is already leaving to see television,” poses Copano. “It’s an audience that when leaving university, is not going to buy an expensive TV, but an expensive ��������Ǥ�����ǯ��������ơ������dzǤ

“ „Nicolás Copano and the creators of 31 Minutos believe that in an atmosphere of change in the Chilean media, young voices have much more space to contribute

Nicolas Copano (right) hosting his late show. Demasiado Tarde. Photo: El Grupo

<<

8

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

In the small southern African nation of Ma-����ǡ���������������ǡ�����������������ȋ��Ȍ������Ƥ���������������������������������������������������������Ƥ��Ǥ�������������������������������������������������������������repayment. Instead of spending the loan to ��������Ƥ�����������������������������������to pay school fees and funeral costs. “It was very ��ƥ�����������������������������������������on. Emergencies would happen and the money would be used for other purposes, which was bad and very stressful,” says Muhango.

Every two weeks debt collectors would knock on Muhango’s door for repayment. Under pressure he was forced to borrow money from other village members to pay back his ����Ǥ�Dz�����������ơ����������������������Ǥ�����whole family was under stress, a few days be-fore paying back the loan I had to run around ��� Ƥ��������� ��� �� ������ ��� ����� ��� ���� ���back. I had debts all over.” After two months Muhango’s loan was repaid in full including ��������� ��� ��������Ǥ� ����Ƥ������������had been started and the family owed loans to other villagers.

THE CRISIS OF MICROFINANCEFrom Malawian farmers to Indian vendors,

Muhango’s story is retold: high interest rates, stringent repayment plans, crippling stress ���� �����Ƥ����� ��������� �����Ǥ� �� ��ơ������������������������������Ƥ�������������������have been telling: one of female empower-����ǡ�������������������������������������������������������Ǥ������Ƥ���������������criticized for being too focused on commer-cial interests. A growing trend has seen non-���Ƥ�������Ƥ������ �������������� ���������commercial enterprises, such as SKS Micro-Ƥ������ ��� ������ ����� ������� � �������� ������ ����������������ơ�����Ǥ�������������������headlines for aggressively collecting loan re-payment from poverty-stricken families and allegedly driving some borrowers to suicide.

by Nina Lex, Canada

6JG�OKETQƇPCPEG�TGXQNWVKQP�KP�VJG������CPF�����ŋU�YCU�JCKNGF�D[�UQOG�CU�C�UCXKQT�HQT�VJG�YQTNFŋU�RQQT��PQY�UWTTQWPFGF�D[�UECPFCN�CPF�EQPVTQXGTU[�KV�UGGOU�OKETQƇPCPEG�OC[�DG�VJG�QPG�VJCV�PGGFU�UCXKPI��6JG�EWTTGPV�ETKUKU�KP�VJG�OKETQƇPCPEG�KPFWUVT[�TCKUGU�VJG�SWGUVKQP�YJCV�ECP�QT�UJQWNF�DG�GZRGEVGF�HTQO�VJG�����DKNNKQP�INQDCN�OKETQƇPCPEG�KPFWUVT[!

6JG�ƇPG�DCNCPEG�DGVYGGPJCPFQWVU�CPF�RTQƇVGGTKPI�

<<

+P�.KNQPIYG��/CNCYKŋU�ECRKVCN��OCKP�OCTMGV�OCP[�XGPFQTU�WUG�OKETQETGFKV�UVCTV�WR�DWUKPGUUGU��2JQVQ��0KPC�.GZ�

�

fEATuRE

$QUVQP�/WJCPIQ�YQTMU�QP�C�HCTO�QWVUKFG�$NCPV[TG�/CNCYK��*G�VQQM�QWV�C�OKETQƇPCPEG�NQCP�KP�QTFGT�VQ�UVCTV�C�ƇUJ�UGNNKPI�DWUKPGUU�Photo: Nina Lex

<<

SKS charged poor women an interest rate �������������������������������������-��������������������Ǥ�����������������������of its borrowers in the state of Andra Pradesh ��������� ��� ������ ������ ��� Ǥ� ������ ��-���Ƥ������ ����������������������������������������Ǥ�����������������������Ƥ����������������ǡ�banks raise interest rates and resort to ag-gressive marketing and loan collection.

In an opinion piece in The New York Times, ���� ������� ��� �����Ƥ������ ���� ������ ������Prize winner, Muhammad Yunus, was shocked by what commercialization has done to mi-���Ƥ�����Ǥ���������ǡ� Dz�������� ��������� �����one day microcredit would give rise to its own breed of loan sharks. Poverty should be eradicated, not seen as a money-making op-portunity.” Yunus founded the Grameen Bank ���������������������������������������������� �������� ���� ����� Ǧ� �������� �����-est and often used brutal methods to ensure repayment. Most of the world’s poor doesn’t have access to banks and savings accounts ����������������������������Ƥ����������������ǡ�������������������������������������Ǥ�������Ƥ-nance can bridge this gap. However, “micro-

credit does not automatically mean develop-ment, it might as well just let families survive when otherwise people would starve,” says Niclaus Bergmann, managing director of ������������������������������Ǧ���Ƥ�������-tution that has been working globally on mi-���Ƥ��������������Ǥ�������������� ������������-����� ���ǯ�� �������� Dz����dz� �����Ƥ�����ǡ� �������������Ǥ��Dz�����Ƥ�����������Ƥ�������������to have a social objective. In most countries, �����������������������������������Ƥ��������-stitution. They might work with the poor, give small loans – but overcharge their clients and don’t have a social objective. They are not real �����Ƥ������������������Ǥ���������������������������������Ǯ�����Ƥ�����ǯ�����������������Ǥdz�

However, some proponents of microfi-nance commercialization say it’s needed to collect funds to expand microfinance pro-jects and reduce dependence on charities. The main challenge for sthe microfinance industry is finding a balance, between be-ing socially focused and economically sus-tainable. “Microfinance without a social objective is just banking. Microfinance without economic sustainability is social

policy or charity. Banking and charity are fine, but microfinance is more than that,” says Bergmann. “That’s why I think doing microfinance in a responsible way is much more demanding and complicated than just being a profit-maximizing banker.”

THE FUTURE OF MICROFINANCEThe idea of microfinance has changed over the last decades. Today microfinance includes much more than loans, such as savings, insurance, money transfer and fi-nancial training and counseling. Past stud-ies suggests the poor have entrepreneurial talents to make microcredit work, but they often need larger loans and more flexible terms than microfinance provides, which is what Boston Muhango hopes for.

Despite his struggles with microfinance, Muhango is still convinced that microfi-nance can help poor Malawians and has a future in developing nations. “With some changes I would use microfinance again. It helped me pay school fees and deal with emergencies. Maybe next time my fish business will make me a millionaire.”

“ „�����Ƥ������������������������������������������������Ǥ������Ƥ�������������������������������������� ��� ����������������� �������Ǥ�������������������������Ƥ��ǡ����������Ƥ���������������������������������������ǡ������������������

��

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

;QWVJ�WPGORNQ[OGPV�KU�CV�CP�CNN�VKOG�JKIJ�INQDCNN[��-GP[C�VJG�UVCVKUVKEU�UVCPF�CV�����CU�QH�������+P�URKVG�QH�VJGUG�ITKO�HCEVU�C�PGY�DTGGF�QH�[QWVJU�CTG�FGVGTOKPGF�VQ�EJCPIG�VJG�VKFG�

ō'XGT[FC[�+�UVTKXG�VQYCTFU�RGTHGEVKPI�O[UGNHŎ

It is a lazy, Wednesday afternoon when I meet up with Steve Nyaga, the proprietor of Pop Inn boutique, a middle-income clothing shop retailing in womens’ apparel. Pop Inn is located in Ongata Rongai, a town in the Great Rift Valley some 22 kilometers from the capital city,

Nairobi. The cool aesthetically lit interior was a great relief from the scorching sun outside. Steve was working on an interior design order online when I walked in, giving the impression that there was more to his life than just selling clothes.

Like many youths all over the world, Steve completed his studies in Fine Art and ������� ��������� ������������ ����������“well paying job.” However, after doing

short contracts as an illustrator for local book publishing firms, it dawned on him that he needed to be creative in order to make a substantial living to cater for his young family then.

“ART IS A PASSION”��� ǡ� ������ �������� �������� ������Ǧ�����clothes with an average start-up capital ��� ǡ� ������ ���������ǡ� � ��������� �����his father. A lover of all things colorful, he

by Kagonya Ngana, Kenya

Photo: Kagonya Ngana

<<

11

fEATuRE

chose not to be just any clothes vendor but a unique one for that matter. Drawing from his artistic background, Steve says that each piece of cloth in his shop is a collected piece of art. This is his unique selling point.

“Art is a passion that I have carried since I was a child and this is what guides me every time I go looking for stocks.” He says.

Necessity as they say is the mother of all invention, and in the four years that Steve has been selling clothes, he has had to perfect his trade. He is now selling new clothes, employed two other youths and most importantly, he has incorporated the use of the social media like Facebook to market his boutique online. The Pop Inn Boutique Facebook page has ������ ��������� ��� ���� ���� ���������������������������������������Ǥ

“Advertising is an expensive endeavor for a small business like mine, word of mouth has worked for me, but I believe online marketing like Facebook can help me reach

an international audience.” Steve adds with a determined look in his eyes.He has recently started working as an independent interior designer and the newly installed studio in his boutique tells it all with beautiful pieces adorning that part of the wall.

“This studio is my latest achievement, I feel ���Ƥ����� ��� �ǯ�� ������ ����� �� ����� �������wanted to do with my life and at the same time build my business.” He says.

His clientele base on the boutique part ������ ��� ���� � ��� � ���� ������������ ������who buy his art pieces are well-educated ������������������������������������Ǥ

TRYING NOT TO BE DEPENDED ANYMOREHumbled when I address him as a job creator, Steve says that it is high time that the youth discard their “dependency on the government” mentality and take it upon themselves to seek ways of empowering themselves economically.

“ I have no role models, I believe I’m the best in my world and every day I strive towards perfecting myself,” he says” I am never �����Ƥ��� ����� ������� ��� ����� ���ǡ� �� ��� ���biggest challenge.”

Half an hour later, I leave the boutique both impressed and inspired. Impressed because, Steve represents many young Kenyans who have decided not to let the prevailing economic hardships to bog them down into the generalized ‘unemployed’ statistics. He has decided to employ himself at the same time creating opportunities for others. I am inspired because if likeminded youth were to create into opportunities for other youths to earn a decent living then unemployment would be unheard of and most economies would be thriving. May be this is wishful thinking but I believe the solution to curbing unemployment lies in the involvement of the youth in the creation of policies and not ������������������������������Ƥ�������Ǥ

Photo: Kagonya Ngana

<<

12

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

Indonesia, the world’s 4th largest country, is used to colliding with crisis. Five decades ������ ���� ������� ������������ǡ� ������ Ƥ���-����� ������� ���� ����� ��� Ǥ� ��ƪ������ ��������Ǥά�����ȋ����������Ȍ�����������������collapsed. This causes social unrest and mul-tidimensional crisis. Desperate about the situation, the idea of national reformation eventually came out.

Another blow struck ten years after the cri-sis. Fortunately, Indonesia has learned much from the previous crisis and has also taken necessary actions, such as intervening into banking system and improving governance �������Ǥ� ������������ ���� ����� ����Ƥ���� ����country this time. Slightly disturbed by the turbulence, the economy was performing ���������������������������Ǥ������ơ������������������ǯ��������ƫ��������������������Ǥ������-

ver, Indonesia has been performing better in the following years.

McKinsey Global Institute even puts Indo-nesia as the world’s 7th largest economy in Ǥ��������� ���������������� ���ǡ� �������predicted that there would be possibility for Indonesia becoming a larger economy than ���������������������Ǥ���ƪ���������������-day’s reality, it seems quite like an attainable yet ambitious goal.

POVERTY IS STILL A NIGHTMAREDespite the economic glory, GDP growth has not been distributed evenly among all citizens, leaving the nation in miserable in-equality. According to the World Bank, pov-erty headcount ratio at national poverty line �����������������άǤ����������������������������� ��� ���������ǡ� ����Ƥ�����������������������������������������������������������Ǥ�Although the trend shows that the ratio has been declining in the last decade, there is an-other alarming signal to be concerned about.

It is common to hear cynical comments say-ing that riches grow richer when poor get poorer. Sadly, it holds partly true in reality as data supports. Inequality has been grow-ing wider, proven by all-time high Gini Index ��� Ǥ� ��������� � ȋ����������� ���������ȌǤ�Despite the economic growth, the poor still unfortunately favours little portion of the na-tion’s prosperity.

Government has imposed some policies, such as conditional and unconditional cash trans-fers, to tackle poverty. However, poverty has ��������������������Ƥ������Ǥ���������������������a fundamental problem that still remains but cannot be eradicated through what govern-����� ���� ����� �����Ǥ� ���� ��ƥ�������� ������������ ����� ��� ���������� Ƥ�������� ���������are the fundamental problems government needs to answer. According to the World ����ǡ����������������ά��������������������������������������ά���������������-holds did not have bank account. Banks have been unreachable for poor Indonesians due to considerably high start-up deposits and

by Nadya Hutajulu, Indonesia

In the midst of recent economic storm, Indonesia stands out with stable GDP growth.

#NVJQWIJ�KPVGTPCVKQPCNN[�TGEQIPK\GF�HQT�UWEEGUUHWNN[�OCKPVCKPKPI�UVCDKNKV[��VJG�KPGSWCNKV[�between the rich and the poor has grown wider. Indonesia is now facing great challenge

in familiarizing prosperity to all.

4GCEJKPI�VJG�WPTGCEJCDNG

13

fEATuRE

administration costs, among others.

RECONSIDERING GROWTHPaying attention to the condition, Bank In-donesia as the central bank commenced a �����������������������������������������������������������Ƥ���������������������������ǡ�especially the poor. This is a way to alleviate poverty as well as to gain sustainable and equitable development for all. The strategy ��� �����������������������������������Ƥ���aspects from strengthening monetary sta-bility, encouraging banking intermediation functions, to strengthening banking supervi-��������������Ǥ�����������������������ǡ�Ƥ��������inclusion is seen as a solution for Indonesia’s challenge in promoting sustainable develop-ment and growth.

�������������������������Ƥ�����������������the strategy. India has realized the idea ear-lier with satisfactory results in lifting the poor ��� ������� ����Ǥ�� ����� ����������� Ƥ��������inclusion as one of main pillars of global de-velopment agenda not so long before the

initiative was announced in Indonesia. With ����������������ǡ�Ƥ����������������������������developing countries dreaming to include the poor to national growth.

AIM HIGHER, AIM WIDERWith tagline “Ayo ke Bank” or “Let’s Go to Bank”, Indonesia has successfully let more ��������� ������� ������ Ƥ�������� ��������Ǥ������� ���� ����������� ��� ǡ� Ǥ� �������� ��-banked people have become the banked peo-ple, eightfold the program’s achievement in Ǥ����������� �����ǡ������ �����������������to consider the building of branchless bank ����������������������������������Ƥ��������services. The program is now being tested in ����������Ǥ

�������Ƥ�������� ��������ǯ�� ����������������-plexity, the challenge now is to balance cor-porate governance quality in banking sector ���������������������Ƥ����������������Ǥ�����-���� ������ ����� Ƥ�������� ��������� ���� �����reachable in countries with better corporate governance. This is another issue for the suc-

�������� Ƥ�������� ���������� ��� �������������-ernance quality is still considerably low in In-donesia. Besides, there are issues regarding Ƥ�������������������������������������������obstacles to the success of the program.

Financial inclusion is more than just changing the status of unbanked people. The inten-����� ��� ����������� �������� ��������� ���Ƥ���-cial system is a sincere strategy to alleviate poverty, reduce inequality and eventually empower the poor to achieve better live. De-spite obstacles and challenges along the way, this program helps the poor become part of economic growth and prosperity of the big-nation-to-be.

Photos: Nadya Hutajulu

<<

14

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

The slow recovery from the global economic downturn has further exacerbated the

effects of the youth employment crisis and the search for jobs has become longer

and longer for many ill-fated young jobseekers. However, unemployment is just the

tip of the iceberg. Underneath this startling situation lie problems that are often

NGHV� QWV� KP�OGFKC� EQXGTCIG�CPF� VJG�RQNKE[� CIGPFC�� VJG�SWCNKV[� QH� GZKUVKPI� LQDU� KU�diminishing and informal employment is drastically rising.

<<

���������� ��� ���� ������� Ƥ������ ���������by the International Labour Organization ȋ���Ȍǡ� ������ ���� � �������� ������ �������unemployed in the world, a drastic increase ���Ǥ���������������Ǥ�Dz��ǯ������������������to be a young person looking for a job and the prospects don’t look like they’re getting

better,” said Theodore Sparreboom, ILO Senior Labour Economist.

With unemployment levels soaring, what happens to the rest of the young people who actually have jobs? Those who have a job feel lucky enough to have found it. Some are jumping from one short term contract to the next. Many accept jobs that are irrelevant to their studies or skills. Others who have no other means of supporting

themselves are often under-employed, �����������������������������������������Ƥ�����or city alleyways of the informal economy. Persistent youth unemployment is just one dimension of the youth employment crisis. Meanwhile, low quality jobs, precarious work, skills mismatch and informal employment remain prevalent. Too many young people Ƥ��������������������������������������ǡ������with a job.

Photo: Michele Lapini

by Emanuela Campanella, Canada

The tip of the�KEGDGTI

15

fEATuRE

�������ǧ������������������The youth employment crisis has left many young people ready to accept anything that is given to them and many employers have taken advantage of this. Take, for example, the buzz around the “intern generation”. Many young people today are jumping from one training or internship to another.

“Internships should always have a training component, since they are about on-the-job training,” said Gianni Rosas, the Coordinator of the Youth Employment Programme at the ILO. “If they use young people for duties that are normally carried out by core workers this can be considered as disguised employment, which can be pursued in labour courts.”

The importance of training has risen as young ����������Ƥ������ ���������������ƥ�������������a job. But widely reported abuses have led to vocal criticism of trainings as a source of cheap and often free labour. “Employers in ������������ơ�����Ǯ���������ǯ�������������������employment. During ‘training’, trainees do not receive a contract of any sort, no insurance of any sort and can be dismissed without any prior notice,” said Farah Osman, a young advocate from the Education for Employment Network. Young people are hesitant in voicing their concerns, because jobs don’t come by easy. Often, they are caught in a paradoxical situation in which they want to gain professional experience but feel

the only way to do so is by working for free.

Equally important, informal employment, especially in developing countries, remains to be a developmental stumbling block. The informal economy is not taxed or monitored by the government, and work is poorly paid and unprotected. According to the ILO, as many as eight out of ten young workers are in informal employment in developing countries. There is a large number of young people in poor quality and low paid jobs with intermittent and insecure work arrangements. After graduating university, Joel Kakaire from Uganda worked as a ���������������������������Ƥ�������������Ǥ�He started working without any formal contract. “We did this work for close to three months but without pay and none of us was willing to discuss issues of payment with the management, because of fear of loss of job,” said Joel. Due to the youth employment crisis, more young people are succumbing to unprotected work.

NOT JUST MORE JOBS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE BUT BETTER JOBS������ �������� ������� ��� �ơ������ ������rights, even if jobs are scarce. While the public has recognised that unemployment �����������������ơ�������������������ǡ�����diminishing of labour rights is sometimes being left unnoticed. This is particularly important for labour markets where young

people are over-represented in informal jobs or trapped in involuntary, part-time or temporary work. Addressing the youth employment crisis is bound up with the over-riding issues of employment growth and economic development. However, it also has its own dimensions that involve more than ����� ������������ǡ� ������ �������� �����Ƥ��actions and policy responses.

Experts suggest that comprehensive employment programs that promote job creation and labour rights are needed. “The best ones combine education and training with work experience and job placement support and also target labour rights,” says Rosas of ILO. “They include incentives for employers to hire disadvantaged youth, such as wage subsidies, tax reductions for a limited period of time”.

In countries where most young people are working in subsistence jobs in the informal economy, programmes that focus on literacy, occupational and entrepreneurial skills, as ����� ��� ����� ��� ������� ������ǡ� ���ǦƤ��������services and markets are most important, likewise with national regulations on labour right violations. The world today is not only confronted with the monumental challenge of creating more jobs for a large number of young people but better jobs for those young people who are struggling to improve their working conditions.

Photo: Michele Lapini

<<

16

MAGAZINEwORLD mAp

Bruna Pickert, BrazilOnline media is the main platformand the population is using itto speak out.

Media institutions in Cambodia havechanged their old perceptions bycreating new multimedia platforms toserve their audiences.

Akanksha Saxena, IndiaLocal media is becoming strong asmainstream corporate-owned mediacut jobs. Digital newsroom, blogs andsocial media promise change.

Dobriyana Tropankeva, Denmark Denmark is one of the leading countriesin social media. Around 85.3% of thepopulation is online. Every new platformis considered trendy & hip.

Camila Salazar, Costa RicaMultimedia newsrooms are the

new north of big newspapers andtelevision media, but journalism

remains one of the professionswith a high unemployment rate.

Sebastián Rivas, ChileIndependent media are using Internet astheir main platform and developing new

business models to keep them viableall the time.

Nina Lex, CanadaThe CBC is combating funding

cuts by targeting younger audiences andinnovative multimedia stories.

Emanuela Campanella, CanadaIt's surviving through passionate

journalists who are jacks of all trades.The people get their news through

print, broadcast and new media.

Michele Lapini, ItalyConcentration of mainstream media

ownership, but an independentinformation is growing up strong.

Freelancers still resist and survive.

17

fEATuRE

Bruna Pickert, BrazilOnline media is the main platformand the population is using itto speak out.

Media institutions in Cambodia havechanged their old perceptions bycreating new multimedia platforms toserve their audiences.

Akanksha Saxena, IndiaLocal media is becoming strong asmainstream corporate-owned mediacut jobs. Digital newsroom, blogs andsocial media promise change.

Dobriyana Tropankeva, Denmark Denmark is one of the leading countriesin social media. Around 85.3% of thepopulation is online. Every new platformis considered trendy & hip.

Camila Salazar, Costa RicaMultimedia newsrooms are the

new north of big newspapers andtelevision media, but journalism

remains one of the professionswith a high unemployment rate.

Sebastián Rivas, ChileIndependent media are using Internet astheir main platform and developing new

business models to keep them viableall the time.

Nina Lex, CanadaThe CBC is combating funding

cuts by targeting younger audiences andinnovative multimedia stories.

Emanuela Campanella, CanadaIt's surviving through passionate

journalists who are jacks of all trades.The people get their news through

print, broadcast and new media.

Michele Lapini, ItalyConcentration of mainstream media

ownership, but an independentinformation is growing up strong.

Freelancers still resist and survive.

18

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

The walls of Cairo’s buildings, the underground stations and metro carriages are emblazoned with employment agencies’ �������������������ƪ����Ǥ�����������������capitalise on the Egyptian youths’ biggest ����������Ǣ� ������������Ǥ� ��� ��� ������ǡ� ��������� ��������� ��� ��������� ����Immigration Khaled Al-Azhry announced ����� ���� ����� ��� ������������� �������� �������������������������������������Ǥ�Therefore, the tiresome commute now brings hope to youths connecting them to those who can solve their problem. At least this is what Mahmoud Eltobgy thought.

HOPELESS Like thousands of Egyptian youths who approach employment agencies hoping to get through the unemployment crisis in

�����ǡ� Ǧ����Ǧ���� �������� ���� ���� ����Ǥ����������������������� ����������������� ���information technology, Eltobgy was not a slacker. On the contrary, he became an entrepreneur and with a group of friends, he established a small company for event organising; a skill he acquired while being an undergraduate.

For quite a while his business was thriving. ���� ���Ƥ��ǡ� �������ǡ� ��������� ������ ����January 25th revolution making it extremely hard for him to maintain the business. “My ���Ƥ���������������������������������������and I ended up stuck between a rock and ����� �����Ǣ� �����Ƥ������ ��������� ������������������������������Ƥ�������������������Ǥ�I had to look for another job,” he says. With an eight to nine years experience in sales, marketing and event organising, Eltobgy started searching for jobs. His quest lasted for over one year and half, but came to no avail. He left his CV at an employment agency, but

the agency mismatched him with a job that he did not qualify for. Living at the heart of Cairo in Abdeen neighbourhood, he set himself on a mission to apply for all sorts of companies disregarding how far they might be; multinationals, medium size ones and local employers.

“I applied even in companies in the area of greater Cairo, but the problem persisted. ���� ������� �ơ����� ���� ������ ��� ��� ������on transportation and not much would be left for my expenses,” he explains. Eltobgy understands that the economic conditions are impacting the job market and forcing �������������������������������ơǤ�Dz�������ǡ�companies now resort to interns from universities to do the jobs for no money or peanuts. It’s inexpensive for them, but it �ơ������������������������Ƥ������������������jobless,” he says.

by Sarah El Masry, Egypt

#DQWV�QPG�OKNNKQP�RCUUGPIGTU�VTCXGN�FCKN[�WUKPI�%CKTQŋU�/GVTQ��1P�UWEJ�C�ETCOOGF�metro, there is really not much to do but wait for the commute to be over. However,

[QWŋF�PQVKEG�C�TGRGCVGF�UEGPG�QH�[QWPI�OGP�QT�YQOGP�SWKEMN[�UETKDDNKPI�UQOGVJKPI�on a piece of paper or frantically pressing the buttons of their phones before the metro

UVQRU��9KVJ�OQTG�UETWVKP[��VJG�CPUYGT�VQ�VJG�TKFFNG�WPHQNFU��RGQRNG�CTG�YTKVKPI�FQYP�the numbers of employment agencies.

9JGP�LQDNGUUPGUU�JKVU�JCTF�6JG�ECUG�QH�'I[RV

<<

'ORNQ[OGPV�CIGPEKGUŋ�RQUV�VJGKT�CFXGTVKUGOGPVU�KP�UQOG�QH�VJG�OQUV�UGGP�RNCEGU�UWEJ�CU�VJG�%CKTQ�OGVTQ�VJCV�KU�WUGF�D[�QPG�OKNNKQP�passengers daily. Photo: Credit: Sarah El Masry

��

fEATuRE

A WAY OUT? Unemployment has always been part of Egypt’s biggest challenges, but right after the revolution and the ensuing political instability, the growth rate of the Egyptian economy plummeted leaving about one million Egyptians jobless. This number increased in the second and third year after ���� ����������� ��������� Ǥ� �������� ������������ � ���� ��� ���� ������������� �����������of the economy. According to “Egypt’s ��������� ���Ƥ��dz� ����� ��� ���� ���������Chamber of Commerce in Egypt, the country ��� ��ơ������ ����� �� ������������ ��������ǡ������������������ƪ���������������������������Ǥά���� �����������ǡ������������Ƥ������Ǥ���������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������Ǥ

Specialists studying the Egyptian labor market attribute the problem of unemployment to the lack of proper education system. The

����������� ��������� ������� ������������ǡ�“A Review of National Policies for Education: Higher Education in Egypt,” stipulates that the current educational policies that depends mostly on rote learning produce students with Dz����������� ��������ǡ� �������Ǧ�����Ƥ�� ��������������Ǧ�������� ������� ���� ����ƥ������academic foundation for employment.” They suggest that certain reforms in the Egyptian national educational system should be implemented to enhance the critical abilities of students and equip them with soft skills they lack to qualify for their career aspirations. These reforms include strengthening links between the labor market and higher education through surveying the skills needed in the market and incorporating them in educational institutions, modernizing technical and vocational education and expanding research capacity.

Eltobgy believes that experience or skills are not his issue, but rather the lack of job

opportunities. That’s why “government should create more jobs and help youths who ���������Ƥ�������������������������������dz����says.Yet, the youth of Egypt are not waiting for the government to solve the crisis. They have ����� ���������� ��� Ƥ��� �����Ǧ����� ����������by launching campaigns and initiatives. For example, the initiative of “Shoghlana” (a job) sponsored by German Society for �������������� ������������ ��� Dz���� Ƥ���� ���Ǧ���Ƥ�� ���������� ����� ��������� ����Ǧ�������workers” and connects job demanders and suppliers. The newspaper publishes every four months providing blue-collar workerswith vacancies that match their skills.

Will the short-term solutions pave the way for the government’s long-term plans? The answer remains unclear at the moment, but what’s palpable is that the youths will not be giving up any time soon, Eltobgy included. “No matter how hopeless it gets, I will keep on searching.”

Photo: UNICEF Facebook page

<<

��

MAGAZINEfEATuRE

���� Ƥ���� ������ ���� ������ ������� ��� ����country’s capital New Delhi. Cricket is India’s most popular game but for many fans this tournament is even more special because it had players drawn from a displaced community - the Kashmiri Pandits. The radio commentators left the listeners teary eyed who were sitting miles away in Jammu. The community had migrated fearing persecution during the height of the

����������� ��������� ��� �� ����� ����rocked the Jammu and Kashmir valley.

��� ���� Ƥ���� �������� ��� �� ���������� ������������������������ƪ�������������������ǡ�������Sharda in Jammu city has only transmission ��������� ��� � ������ ������� ������� ǡ� ���� ���works as an emotional connection for friends and relatives displaced and dispersed from their own land.

BRIDGING THE GAP“The elderly anguished in the pain of losing their home and hearth. The young are

disconnected with the past and have not been exposed to the rich cultural history. Struggling with the feeling of getting alienated from our traditions, language and culture, we decided ��� ���� ��� �� ���Ǧ���Ǧ���Ƥ�� ���������� �����dz��������� ������� �������ǡ� ǡ� ���������� ���Radio Sharda and a journalism graduate.

The studio with digital recording facility has ���������������������������ƥ��������Ǥ�������out pit right outside the porch anchors the foot ���Ǧ��������������������������Ǥ����� �����and Kashmir government leases the building. �� ������ ���� ���������� ���ơ� ����������� ��� ��

by Akanksha Saxena, India

On air: OCMKPI�YCXGUDz����������������������ǤǤǤ���������������dz����������������������������ǯ�����������Ǩ�

A radio commentator rising to his feet in excitement almost screaming on the microphone

HTQO�C�OCMGUJKHV�EQOOGPVCT[�DQZ�CV�VJG�HCT�GPF�QH�VJG�ƇGNF��6JG�DCNN�JKV�VJG�DQWPFCT[�HQT�HQWT�TWPU�CPF�,COOW��C�VGCO�HTQO�0QTVJ�+PFKCP�UVCVG�QH�,COOW�CPF�-CUJOKT��YQP�VJG�ƇPCN�match of the cricket league that went down to the wire.

<<

Photo: Akanksha Saxena

21

fEATuRE

radio jockey, contributors, a sound engineer ���� �� ���������� ������� ��������� ��� �ƥ���executive runs the day fares .

This resource crunch has not dampened the spirits. “During our religious festival Herath this year there was a record surge in the numbers of people tuning into our station. We had Kashmiri Muslim Bhakti (devotional) singers for the special telecast on the day and we were full of song requests. Interestingly, Muslim poets singing Hindu Shaivite devotional songs are popular choice of Kashmiri Pandits. They sometimes sing better than the Pandits.” recalls Hangloo.

The community radio station had begun for Kashmiri Pandits but it enjoys unswerving listenership among Kashmiri Muslims too. The radio has helped bridge the gap between two communities. “Fifteen thousand families listen to us by FM in Jammu city. We do know of people in Tral, Srinagar and other places in the valley supporting us. More tune in on Internet to listen. Sometimes economic viability and team capacity creates hurdles.” explains Hangloo.

A DAUNTING TASKThe community radio movement is not ���� ��� �����Ǥ�������� � ���������� ������stations in India have a viral outreach to people who use transistors costing as low ������� ��������������������������������������aspirations. Indian government plans to help �������������������������������������Ǥ�

A daunting task for media here is to cater ��� �� ������� �������� �������� ����� Ǥ� ��������people belonging to complex castes (a social division), regions and religion structures. The problems intensify with limitation of media in outreach, lack of resources to sustain local media and viciousness of hunger and livelihood that drive people out of their native place to search for work in cities.

People speak in numerous tongues. Nearly ά���������������������������ȋǤȌ������Ǥ�TV is beyond the reach. Electricity has not reached many of these villages. Community radio in India therefore has a huge potential to transform local economy and social mores of small hamlets and towns of this India. It is also bringing together those communities that have been traditionally marginalised through local community participation.

Socially relevant broadcasts are empowering vast majority of rural youth employed in the informal sector by connecting them to prospective employers. The range of this change is from bringing silent change in Kashmir valley to the tribal districts of Jharkhand and Chattisgarh in central India that have been hit by left-wing insurgency.

Community radios in India are licensed to NGO’s and universities. Sustaining community radio in India is a challenge. Since they are not run by private groups and the greater aim is generally to be socially relevant, generating revenue remains a tough task.

Big advertisers do not trust the quality of transmission or its intent, so local shops and businesses are the only sources of revenue besides small funding. On an �������� �� ���������� ������ ������ ǡ $ annually to run. A chance of good revenue generation is limited. The corporate groups can come forward and support community radios by integrating Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) approach.

ON A HIGH NOTEA testimonial on the Radio Sharda page on facebook by a listener Usha Nehru writes “Kashmiri music sooths my nerves that I had forgotten from more than thirty years. I don’t feel that I am lonely anymore. Thanks to all of you who run this radio station.”

However sustainability and funding remain crucial problems for community radios. Advertisers and mass communicators wishing to reach rural audiences can bring a ����������ơ�����������������������Ǥ�

The community radio has a long way to go but the start has been on a high note.

“We are optimistic of change and we’ve helped people overcome the feeling of loss and dispossession. We say it in the tagline ‘Booziv ti khosh rooziv’ i.e listen and be happy” smiles Radio co-founder Hangloo. These airwaves may just change things in India.

“ „������������������������������������������������Ǥ���������community radio stations in India have a viral outreach to people

<<

Photo: Akanksha Saxena

InterviewingdatabasesAfter the Fukushima nuclear disaster a group of citizens decided to collect data about the radiation. The analysis of this information by the media is an example of data journalism, a way to tell stories where statistics and computer engineering mix.

Photo: Suy Heimkhemra

<<

Interviewing an excel database or learn-ing how to speak with numbers doesn’t seem like traditional journalism. The reason is simple: it is not. It is called data driven journalism (DDJ) – translating data with public interest to audiences.

“Data journalism is about asking the important questions,” explained Holger Hank, Head of Digital Division at the Deutsche Welle Akademie. With the out-burst of technology in newsrooms, this practice – even if it’s not new – has be-come a great tool for media specialists. Its secret lies in combining skills of tradi-tional journalism with statistics, web de-velopment, computer engineering and design to tell original stories that are

useful to people.

“Data doesn’t speak and we have to do the right questions. In order to make the right questions we have to know how to approach data”, said Giannina Segnini, a data journalist from Costa Rica. There are numerous examples: using container registration numbers to investigate or-ganised crime or analysing databases to see how money is spend in communities.

Seek AnD you WIll fInD one of the big challenges this type of journalism faces is non-accessible infor-mation.

“If you look at what’s available, it’s just the tip of the iceberg,” said Christian kreutz from the German open knowl-edge foundation. But the tip isn’t small. A lot of documents can be found online

in government or organization’s sites.

“There’s a political movement trying to open data, and a lot of open software”, said Mirko lorenz, an Information Archi-tect from Germany. on the other hand, when data doesn’t exist or isn’t avail-able an option is to build it. for exam-ple, in Japan after the 2011 earthquake, a group of citizens collected information about radiation in different communi-ties, since they didn’t trust the official reports.

An oppoRTunITy foR SMAll MeDIAeven though some of the best examples of DDJ come from big media organiza-tions, this way of telling facts can be a great opportunity for small newsrooms. “It can be achieved at low cost”, stated lorenz. Instead of ten people working on a story, one or two people can be asking questions to a data set.

According to Segnini, it’s easier to make change when you have a small news-room. “This is not really about money, it’s not rocket science. It is more about the will to change things”.

by Camila Salazar, Costa Rica

22

MAGAZINEreportage

Reading the peopleMa’an is the most important news agency in Palestine. Raed Ohtman, its founder, says the key to its success has been to be the voice of those who can’t speak.

“nowadays all you need to cover news is a laptop”. It was 2003 and Raed othman had an idea in his head; he hadn’t found a place to read all the information about daily life in pales-tine yet. The solution was to create some-thing entirely new: an independent news agency that collects news from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The following year he created Ma’an, which means “together” in Arabic. The idea was to use the power of the media for the people. othman, who was a panelist in the workshop ‘news for Social Change’ at the DW GMf 2013 in Bonn, says his phi-losophy is simple: make the media get in-volved with people.“If you don’t go with them, don’t listen to

their stories and their problems and don’t publish daily life news, they will not read you”, he says.

fInD eveRy SToRyMa’an has become the largest news agency in the country: today 85 percent of pales-tinians regularly view its website, which is read by over 3 million people every month. It also has 10 radio stations, which are heard by nearly 55 percent of the population, as well as the second biggest cable channel. He describes them as his “three arms”.

According to a survey cited by othman, 82 percent of those who support Hamas and 86 percent of supporters of fatah consider Ma’an as “independent”.

“We started to read the people. We went to a lot of little villages and towns all over the country to find stories and news”, he says. In addition, their english website is regarded as a worldwide reference for un-

derstanding the reality of the palestinian people.

othman sums it up: “now we are the main source about palestine for palestinians and everyone else.”

A neW WAy of DeBATeMa’an has also taken a leadership role in the discussion regarding complicated is-sues in palestine. on June 24 this year, the Tv channel will present the final of presi-dent, a reality show in which about 1200 palestinians applied with the idea of being ‘elected’ the new president. Although it isn’t a real election, the program has high ratings: the final chapter will be covered by more than 100 journalists.

And for othman it is another opportunity to achieve Ma’an´s goals: “In the show, we speak about democracy, human rights, the struggle with Israel and how to end pover-ty. We speak about big issues”.

by Sebastián Rivas, Chile

Photo: Biayna Mahari

<<

23

reportage

Sustaining social change through news“Credibility of media upheld by sincere journalists combined with a concern for issues of importance about people can bring a real social change,” said Nihar Kothari, Managing Director and Executive Editor of publication Patrika, based in Jaipur, India.

Photo: Biayna Mahari

<<

Kothari was part of a panel in a media workshop at the Global Media Conference hosted by Deutsche Welle taking place in Bonn, Germany. The workshop looked at how to cover news for social change: me-dia’s emerging value proposition. Speaking on the issue, Kothari explained that the future of news organisations lies in moving to higher value-based activities like engaging powerfully with communi-ties, becoming a conduit between margin-alised sections and the government. He also stressed that covering news and activ-ism should not be mixed. “Activism is not for journalists. But journalists can convince readers about a problem, cover the issue with stories and keep a sustained effort at

generating public concern about the issue.”

“Writing on an issue supported by facts and objectivity can result in sense-making and action.” Kothari comes from a news organisation with bureaus in eight states in India. They boast of a robust network of 3800 journalists and stringers. His news organization, Patri-ka, has become a media action group over the years. The stress has always been on the community correspondents who bring ground reports that the publication can pick up to become agents of change. The panel emphasised that reports can more often ����� ��� ���ƪ�������� �������������� ���������-tisers who essentially support the newspa-pers and publications by buying advertis-ing space in the publication. The challenge, however, is to balance news and revenue generation without compromising truth.

“We reported on the mobile phone tower radiation problem around areas in Jaipur. The radiation emitted was found to have ������������ ����� ������� ��Ƥ�� ��� ��� ��� ��residential area. People living around the mobile tower had developed medical condi-tions ranging from irritability to more seri-ous ailments.”

“A lot of people got in touch with us and asked us for a solution. We ran a campaign for change and wanted the telecom compa-nies to adhere to the norms and maintain radiation standards. Now Rajasthan is the only state in India with no mobile towers in school buildings. That was a court ruling that achieved such intervention,” explained Kothari. “We ended up losing substantial revenue by our telecom partners. Even the cost of the property made by builders in the vicinity of mobile towers fell. We also got less adver-tisement from them,” he said.

“There is a choice that publications have to make as to whose problems they want to highlight. In the process we may lose rev-enue but the truth must be investigated and facts must be uncovered.”

by Akanksha Saxena,India

24

MAGAZINEreportage

Growth, yes!But what kind of growth?The world’s audacious bid to improve human wellbeing yet conserve resources has not been ignored. Summarised as green economy, talks of its enormous possibilities as well as the flipsides have heightened since the Rio+20 Conference, The foremost targets are to improve wellbeing and social equity while trimming environmental and ecological risks.

“There ought to be talks of sustainable econo-my rather than green economy, because there have to be fair conditions globally concerning access to resources and access to energy,” said Wilfried Kraus, Deputy Director General of Di-rectorate Sustainability, Climate, Energy, Fed-eral Ministry of Education and Research, Bonn.

While Kraus would rather have sustainable economy than green economy, Head of Corpo-rate Responsibility at REWE Group, Dr Daniela Buchel believes it is just enough that the for-

mer is a component of the latter.

Dz������������������������������Ƥ������������������������ǡdz������������ǡ���������������������ơ���perspectives on how to drive the green econo-my plan.

“It is important to have sector-wide initiatives,” she added. “We have to think about how we can award and reward our suppliers for positive change towards green economy. We have to have a sort of competition in the home market on these things.”

CAN IT WoRK? AND HoW?Speakers at the conference believe so.

They offered critical recommendations.

“We have to reduce Co2 emission into the atmosphere and we have to reduce energy consumption by 50 percent,” Kraus said.

“We have to really focus on the future of our lifestyle,” said Rudi Kurz, a professor of economics at Pforzheim University, Ger-many. “We have to know the future of our actions and their consequences.”

For Andreas Loschel, professor of econom-ics at University of Heidelberg, support of the people is crucial. “The policies are nec-essary,” he admitted. “But it is important to bring a lot of people behind the regula-tions.”

THE IDEAL TyPE oF GRoWTH“Growth is important but you have to con-sider what growth you want to achieve,” said Buchel. “Is it growth in terms of quan-tity or growth in terms of quality?”

It’s the latter. “It has to be a growth in terms of quality and not quantity,” she said. “That is what we want!”

by ‘Fisayo Soyombo, Nigeria

Photo: Suy Heimkhemra

<<

25

reportage

Economic growth and the Global Peace IndexAustralian Steve Killelea, founder and chair-man of the Institute for Economics and Peace, which is based in New York and Sydney, sheds light on the connection between economics and peace and the results of this year’s GPI.

What is the importance of peace for a coun-

try’s future?

If you look at the attitudes, institutions and structures that create peace, they also cre-ate the same societies, which are economi-cally thriving, environmentally friendly, have strong social policies and adequate economic distribution. This eventually creates the op-timal environment for human potential to ƪ������Ǥ

What does this year’s Global Peace Index

tells us?

����Ƥ������������������ǯ�� �������������������

���������������������������������������ǡ�������ǣ�a continuing shift away from nations taking up arms against one another and towards ���������������������������ƪ����Ǥ����������-tor associated with this is that the peace gap between countries under authoritarian re-gimes and the rest of the world is becoming larger. This can be seen with the slowdown of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which are re-����������������������ƪ������������������ǡ�����ǡ�Somali and Syria, which recorded the great-est score deterioration in the history of the �����Ǥ� How are peace and the economy linked?

Violence directs resources away from pro-ductive uses and towards containing violence and the consequences of violence. People do �������ơ�����������������������������������-�������ƥ�������������������������Ǥ

Does a country’s economic growth ensure

development and progress?

Economic growth generally does help create peace, security and develops a country. But it depends how economic growth is distributed throughout society. If economic wealth only goes to a few people, peace and security will be impeded.

Has the rise of BRICS nations (Brazil, Rus-

sia, India, China and South Africa) led to

greater human security and peace?

If you look at the BRICS countries, generally their attitudes, institutions and structures are fairly developed in their level of peace. There-fore that means we should see economic pickup in those countries.

For more information on this year’s Global ���������������������Ǥ�������Ƣ�������Ǥ���

�����������ǡ�������

Photo: Suy Heimkhemra

<<

26

MAGAZINEinterview

Global Governance:Blueprint for a Sustainable Work Economy?What is Global Governance and how we can achieve it? This was the main question discussed at the plenary session of the Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum.

Photo: Michele Lapini

Aart de Geus, the Chairman of the largest pri-����� ���������� ���Ǧ���Ƥ�� ����������� �����-many, Bertelsmann Stiftung, shared a con-����ǡ�����������������������������ǣ�Dz��������in one Earth, but we use it like we have 1.5 and in few years we might have 0.1”. The numbers are clear and action needs to be taken. But what would be the most appropri-ate method? For de Geus, there is a need to create a new global agenda and reformulate �������������������������������Ǥ�Dz�����������that smaller population lives in real poverty, but there is an increasing inequality that needs to be addressed.” �����������������������������Ǧ �������������ǡ���������������������GIZ, the German federal enterprise for sustain-able development, describes global govern-����� ��� ����������������Ǥ�����Ƥ���� ��� ������-thority, which is the ability to enforce norms,

rules and regulations on an international level. The second dimension is the capacity, which ���������� �������� ������� ���� ������� ������-ance is able to answer to the needs of the peo-���Ǥ���������������������������ǣ��������������-ers can access superior levels. ��������������������������ǡ�����������-������ ���������� ���� �����������ǡ� ���������that achieving global governance requires ����������� ���������� �������� ��ơ������stakeholders. Governments have to collabo-rate more with responsible business, civil �������ǡ�����������������������������������results. �������������������������������������� �����ǡ� �� ������� ������������ �ơ�����������������������������������������ǡ�������about the important role of media in global ����������Ǥ������������� ���� �������� ��� ��-�������� ���������ǣ� ���� �������� ���� ���������media are under tremendous pressure, they have to cut costs and, at the same time, they have to produce around the clock.

�Dz����������������������������������������ǯ��have the capacity to produce so fast. So they copy-paste report stories from the big US wires. That makes accurate reporting really ��ƥ����Ǥdz�� Although traditional media outlets are un-der pressure, de Geus sees opportunities in the new media information era. For him, the �����ơ��������������������������������-ing journalism research. Social media also has great power. Public image is important ��������������Ǥ����������������������������and shaming in social media has turned dog-gy policies of some big corporations to more sustainable strategies. ��� ���� ���� ��� ���� �������ǡ� ��� ������� ��-dressed the plenary full of journalists, en-couraging media makers to focus not only on negative stories, but to report more about best practices. Positive reporting can contribute to our sense of achievement and ������������� ���Ƥ�������� ���������������-��������������������ơ������������������� ���society.

�����������������������ǡ�Bulgaria

<<

27

feature