Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care Populations

-

Upload

jasmine-tucker -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care Populations

Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3): 147-167REVIEW ARTICLE 1173-8790/04/0003-0147/$31.00/0

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved.

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in ManagedCare PopulationsImproving Clinical and Economic Outcomes

Rachel Czubak, Jasmine Tucker and Barbara J. Zarowitz

Pharmacy Care Management, Henry Ford Health System, Bingham Farms, Michigan, USA

ContentsAbstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1471. Managing Drug Therapy Outcomes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

1.1 Overuse, Misuse, and Underuse of Medications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1501.1.1 Overuse of Medications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1501.1.2 Misuse of Medications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1511.1.3 Underuse of Medications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1511.1.4 Implications in Managed Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

2. Factors Influencing the Prescribing of Medications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1522.1 Aging Population . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1522.2 Availability of Healthcare Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1522.3 Direct-to-Consumer Advertising . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1522.4 Adverse Effects of Medications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

3. Improving Prescribing Practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1533.1 Private Sector . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1533.2 Education by Academic Detailing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

4. Evolution of a Strategic Framework for Providing Quality Healthcare . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1535. Chronic Care Model: Changing Care Delivery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154

5.1 Community Resources and Policies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1555.2 Formulary Management . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1555.3 Evidence of Effectiveness in Reducing Cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1555.4 Physician Report Cards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1565.5 Self-Management Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1565.6 Abundance of New Drug Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1575.7 Practice Guidelines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1575.8 Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1595.9 Physician Incentives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1615.10 Tools for Improving the Medication Use Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

6. Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

Managed care presents interesting opportunities to optimize clinical and economic outcomes related to drugAbstractprescribing. There are very few randomized controlled trials that have evaluated methods to educate orincentivize physicians, implement formulary management or guideline tools, profile physicians, and implementpharmacist interventions to ensure optimal drug prescribing. Single methods of optimizing medication outcomeshave not been shown to be as effective as multifaceted approaches. Specific reinforcement of the message at thetime of prescribing has been shown to improve antibiotic prescribing in patients with chronic bronchitis andimprove adherence to treatment guidelines for the management of patients following myocardial infarction.Results from a randomized controlled trial showed that changes in pharmacy benefit design decreased costs and

148 Czubak et al.

medication utilization. Much of the literature evaluating the effectiveness of utilization management techniquesin optimizing drug therapy outcomes is retrospective in nature. However, pharmacist intervention has beenshown to reduce polypharmacy in a randomized controlled trial in the elderly. Appropriate prescribing scoreswere improved and this improvement was sustained at 12 months post intervention.

Clinical pharmacy services have been shown to reduce hospital admission and hospital days, decreaseprescription and total health care costs, reduce the number of drugs per patient, and improve attainment of targetlow density lipoprotein cholesterol values.

Recent analyses have shown that there is a higher likelihood of achieving improved outcomes of care whenthree or more of the following aspects of healthcare are impacted: patient self-management, clinical informationavailability, redesign of the way care is delivered, decision support strategies, the healthcare system, and theprovider organization. In a review of interventions designed to improve the care of patients with chronicillnesses, process variables were improved when one or two of the aspects were improved. Outcome variableswere improved when three or four of the aspects were impacted.

There continues to be great focus on improving the quality of care in managed care environments. With thepassing of the Medicare legislation in the US, by 2006 the vast majority of citizens will receive healthcare inmanaged care environments. Additional research designed to explore methods of optimizing drug therapyoutcomes is needed to characterize the most efficient, transparent, and least costly ways to reduce misuse,overuse, and underuse of prescription drugs.

The statistics for healthcare spending in the US, released by the A Medline search (January 1996–August 2003) was conductedof English-language studies containing original, quantitative refer-US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2003,ences pertaining to the achievement of managed care outcomes.revealed an explosion in US healthcare spending that has beenSearch terms included ‘drug therapy outcomes’, ‘overuse’, ‘mis-sustained for the past 5 years.[1] In 2002, US healthcare spendinguse’ and ‘underuse’. Articles using pre/post methodology, ran-reached $US1.6 trillion, representing a 9.3% increase over thedomized/controlled designs and longitudinal designs in severalprevious year.[2] Among categories reported, prescription drugareas of managed care practice are discussed.spending grew at the fastest rate of 15.3%, compared with a 9.5%

rise in hospital spending and a 7.7% increase in spending on1. Managing Drug Therapy Outcomesphysician services.[2] The success of managed care in controlling

healthcare costs during the 1990s has diminished with recent Optimizing drug therapy outcomes cannot be achieved withoutincreases in the cost of healthcare services and growing utiliza- the implementation of a multi-pronged approach. There are severaltion.[2] Diminished cost control is especially obvious with the key components to achieving managed drug therapy outcomes. Insurge in expenditures for prescription drugs. The prescription drug managed care settings, the mission of organizations is to assurecost burden has forced healthcare plans to explore a variety of safe, appropriate, and cost-effective drug therapy. Pivotal com-strategies aimed at containing the costs associated with providing ponents needed to fulfill the managed care pharmacy mission areprescription drug coverage. Optimizing clinical outcomes to pro- formulary management, contracting strategies, claims manage-vide exemplary quality has been the focus of managed care, large ment, data and reporting, utilization management, medicationemployer groups, purchasing coalitions, and credentialing agen- safety, and clinical pharmacy services (table I).cies.[3] The value of healthcare can be improved through the Achieving optimal drug therapy outcomes begins with theenhancement of quality and the reduction in associated costs. The careful review and selection of medications within the formularyrising cost of prescription drug coverage and barriers to reducing to ensure that only those drugs that meet efficacy, safety, tolerabil-costs are issues that are fundamental to optimizing therapeutic ity, and cost-effectiveness criteria are chosen. While new molecu-outcomes. The US Institute of Medicine (IOM) has defined 20 lar entities can be reviewed individually, tactics that have helpedchronic conditions in great need of improved healthcare out- to ensure appropriate drug use within the Henry Ford Healthcomes.[4] These conditions represent patients who are at risk of System in Michigan, USA include condition treatment reviews topoor outcomes, where clear evidence exists that better outcomes determine the role of the new medication in therapy. For example,can be provided. This paper reviews strategies for optimizing drug with the availability of alefacept for the treatment of moderate-to-therapy outcomes in managed healthcare. severe cutaneous psoriasis, an evidence-based review covering

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care 149

patients from receiving the medication without undergoing anindividualized assessment of their history and condition. A quanti-ty limit was placed to prevent long-term use of the medicationwithout the necessary lymphocyte monitoring. Educational mater-ials were disseminated to physicians and other healthcare profes-sionals within the healthcare plan and the delivery system topromote the appropriate use of alefacept. Claims data, outliningphysician-prescribing patterns, are used to monitor the effective-ness of these strategies to ensure the appropriate use of alefacept.

Clinical pharmacists, nurses, or case managers who routinelymonitor high-risk, high-cost medications and patients, conditions,and drug therapy, work closely with prescribing physicians toensure that drug use is appropriate and that patient safety isassured. In a prospective, concurrent, or retrospective fashion, dataare reviewed to evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and cost result-ing from the strategic decision to place alefacept on the formulary,with restrictions. Based on the prescribing data and evolvingmedical evidence, modifications of the pharmacy managementplan are made to assure that the medication is available to patients

Table I. The inter-relationship of key components for achieving optimalclinical and economic benefits in managed care environments

Decision phase

Formulary management (e.g. evidence-based decision making;guidelines and drug policy)

Contracting and rebates (e.g. incentives for pharmacies and physicians;drug market share incentives)

Benefit design (e.g. right-size employee cost share)

Data and systems phase

Claims management (e.g. proactive cost controls; prior authorization;quantity limits)

Data reporting and measurement (e.g. physician report cards; data-driven system decisions)

Care delivery phase

Utilization management (e.g. prescriber education and behavioralmodification)

Medication safety (e.g. reduce unnecessary medications; decreaseoveruse and misuse of medications)

Clinical services (e.g. specialty clinics such as: lipid, anticoagulation,asthma; linkage to disease management)

who meet the criteria for treatment, that it is used safely, and forthe approved duration, with resulting clinical improvement.

psoriatic therapeutic strategies, their comparative effectiveness,Physicians in reimbursement arrangements without the burden

adverse effects, and costs, was performed. The findings wereof financial risk are motivated to change their behavior if given

discussed with medical experts in dermatology and rheumatologyfinancial incentives (also see section 5.9). In the physician incen-

to develop a consensus about the likely utility and impact oftive program of the Health Alliance Plan, the top 200 most

alefacept in the treatment of psoriasis. The process began prior toexpensive drugs are excluded in the calculation of the incentive to

drug approval by the US FDA.avoid interjection of an adverse selection bias. Thus, alefacept

By the time the psoriatic drug review was presented to the utilization would not be a component of the physician incentiveAmbulatory Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee of the Henry program. However, drugs commonly used to treat chronic condi-Ford Health System, the place of alefacept in therapy was estab- tions are included in the incentive calculation and weigh heavilylished, with the delineation of required monitoring parameters and on per member per month drug cost.drug-use criteria to assure that only those patients who are likely to There are economic strategies available to achieve the desiredbenefit from this treatment will receive the drug. Because the therapeutic outcomes and to control rising drug costs. Theintravenous and intramuscular routes of administration require alefacept example can be extended to elucidate the value of benefitdifferent doses, and the intramuscular dose of 15mg is associated design (see table I) in managing pharmacy outcomes. Many healthwith much higher costs without additional therapeutic benefits, the maintenance organizations (HMOs) have developed, or are in thecommittee approved only the use of intravenous administration of process of developing, strategies to manage high-cost injectablealefacept for patients enrolled within the Henry Ford Health Sys- and infusible medications, such as alefacept. These medicationstem. Given that the treatment of cutaneous psoriasis with alefacept are typically covered in the highest co-payment tier where theoccurs in the ambulatory environment, only the Ambulatory member contribution is substantial. It is common to establishPharmacy and Therapeutics Committee evaluated the drug. Med- vendor relationships with specialty pharmacies who become theication reviews are coordinated between the inpatient and ambula- sole provider of infusible or injectable drugs. Under these businesstory committees when pharmaceutical drugs are likely to be ad- relationships, drug use is regulated, monitored, and managed byministered in both settings. the specialty pharmacy to assure that drugs are used within estab-

Using the pharmacy care management model table I as a guide, lished guidelines and that optimal outcomes are achieved. Further-criteria were developed to restrict the use of alefacept to the more, given that the volume of infusibles and injectables pur-situations and conditions of greatest benefit and lowest cost. chased by specialty pharmacies is large, volume discounts arePharmacy claims edits were implemented to prevent ineligible passed on to the HMO and help to keep costs down.

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

150 Czubak et al.

1.1 Overuse, Misuse, and Underuse of Medications Health in the eValue 8 survey,[11] used by employer groups in theannual review and purchase of employee healthcare insurance.

Numerous examples of overuse, misuse, and underuse of medi-Perhaps the greatest opportunity to improve pharmacy out-cations exist in the literature.[12-16] Yet there are few studiescomes derives from the excessive waste within healthcare. Ac-providing evidence that quality is improved when controlled inter-cording to the US IOM’s series about American healthcare, theventions are implemented to decrease overuse, misuse, and un-quality of healthcare has suffered for a variety of reasons, includ-deruse of medications (table II).ing the overuse, underuse, and misuse of services.[5-7] In 1990,

Hepler and Strand[8] characterized problems of medication1.1.1 Overuse of Medications

overuse, misuse and underuse, as drug-related problems. Drug-An example of the overuse of medications is that of antibac-

related problems, later estimated to cost more than drug therapyterials in upper respiratory tract infections, which has been the

itself, must be a focus of managed pharmacy outcomes.[9]

subject of numerous reports throughout the world. The best experi-The National Council on Quality Assurance and the Health ence in reversing the consequent increase in antimicrobial resis-

Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) has introduced tance patterns occurred in Finland in the early 1990s when nation-quality measures of overuse, misuse and underuse related to drug ally, healthcare providers worked together to decrease unnecessa-therapy and condition management in an effort to reduce waste ry antibacterial use.[23] Gonzales et al.[17] produced impressiveand improve healthcare quality.[10] An example of a HEDIS mea- reductions in antibacterial overuse for patients with acute bronchi-sure for overuse is the use of antibacterials in viral upper respira- tis as a result of the provision of physician and patient education attory tract infections. An example of a HEDIS measure for misuse the beginning of the cough and cold season, as well as on the dayis the ratio of long-term controller therapy to short-term reliever of the physician visit. Personal reminders were more effective thantherapy for patients with asthma, where the misuse of short-acting mailed reminders, and ‘just-in-time’ information reinforced theβ-adrenoceptor agonists and the underuse of inhaled corticoster- message resulting in the greatest reduction of antibacterial use.oids occurs. The use of β-adrenoceptor antagonists after a myocar- Successful changes in prescribing practices incorporated educa-dial infarction is an example of a HEDIS measure of underuse. tion, guidelines, reminders, one-on-one discussion with patientsThese measures are scored by the National Business Coalition on and physicians before and at the time of the visit for antibacterials.

Table II. Studies assessing the effect of correcting the overuse, misuse, and underuse of medications on the quality of healthcare outcomes

Study Study design Study focus Intervention Results

Overuse

Gonzales et al.[17] Randomized Prescriptions of Physician and patient education prior Reduction of unnecessary(1999) controlled trial antibacterials in to and at the time of the visit antibacterial use

acute bronchitis

Zarowitz et al.[18] Longitudinal Polypharmacy (>5 Pharmacist intervention, physician 50% reduction of cost and utilization(2003 and from chronic medications) and patient education of medicationsunpublished data)

Misuse

Andrade et al.[19] Retrospective Prescriptions of Implementation of a prescription OTC switch program reduced(1999) histamine H2- to an OTC switch program prescriptions of H2-receptor

receptor antagonists by a factor of 1.5. Noantagonists increase in physician visits

Brufsky et al.[20] (1998) Prospective Prescriptions of Education and performance Increase in cimetidine market shareH2-receptor feedback of 53.8%, which translated to aantagonists saving of $US1.06 million annually

Underuse

Bloome et al.[21] Longitudinal Prescriptions of Enrollment of patient in a lipid clinic. Drug doses increased and the(2000); drugs for lipid Pharmacist management proportion of patients reaching LDLSmits et al.[22] (2003) disorders cholesterol goal was increased to

72%

LDL = low-density lipoprotein; OTC = over-the-counter.

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care 151

The value of this intervention was demonstrated in a multicenter, misuse of H2-receptor antagonists was corrected by alternativecontrolled, randomized design and resulted in the best example of recommendations, and thus, medication use was improved.behavioral changes attributed to specific interventions.[17]

1.1.3 Underuse of Medications

Polypharmacy A noted example of underuse is in the treatment and preventionof coronary artery disease with the use of appropriate lipid-Another intervention to decrease medication overuse was con-lowering medication. Studies have shown that approximately onlyducted at the Henry Ford Health System (as previously pub-31% of patients with coronary artery disease achieve low-densitylished[18] and from unpublished data). Patients receiving five orlipoprotein cholesterol target values associated with efficacy.[24]more medications concurrently, on a chronic basis, were identifiedThe business case for quality has been made by Smits et al.[22] forfrom pharmacy claims data and identified for prospective inter-effectively implementing approaches to optimally manage lipidvention. Pharmacists evaluated the likelihood that medicationstherapy. In this case study published by the Commonwealth Fundwere causing drug-related problems and intervened with the physi-in New York, USA, the Henry Ford Health System noted a returncian and patient, where appropriate. Drug doses were adjusted,on investment of 2 : 1 associated with a lipid clinic model ofunnecessary medications were discontinued, necessary medica-optimizing drug therapy.[22] Prior to the intervention, as much astions (that were not being administered) were initiated, drug$US6.5 million was wasted annually in drug therapy that wasinteractions were anticipated and avoided, and drug therapy wasconsidered to be inadequate to produce the desired therapeuticstreamlined to improve the affordability of medications for pa-outcome. Despite the cost savings associated with the lipid clinic,tients with chronic illnesses. As a result of the program, drug costthe service was not expanded because of the fixed costs, for whichand utilization were decreased by an average of 50% 6 monthsno new revenue was generated. In a fee-for-service model, servicefollowing the implementation of the intervention. The greatestreimbursement could produce revenue that would offset fixedlikelihood of modifying therapy was in high-risk specific targetedcosts and generate a profit. However, in the managed care capitat-areas where the implications of drug therapy complications coulded environment, higher fixed costs, associated with improvedbe associated with harm. The design involved a prospective cohortquality, do not result in increased revenue. The case-study makesof patients who were followed longitudinally, but did not involvethe business case for quality while defining the complexity of therandomization. However, the design of the study attempted todecision to provide each service.control for bias because the patients served as their own control

and were re-examined multiple times over 3 years.1.1.4 Implications in Managed Care

1.1.2 Misuse of Medications Characteristic of each of these successful strategies (underuse,overuse, and misuse) is the integrated changes in the model ofMisuse can occur when more expensive medications are usedcare. Each involved technology and information to identify eligi-instead of lower cost alternatives, given that one of the greatestble patients, education of patients and healthcare professionals,concerns in healthcare today is cost. The correction of medicationimprovements in the delivery of care or care organization, andmisuse was demonstrated in two trials involving histamine H2-either community support or public policy changes. In thesereceptor antagonists.[19,20] In the first trial, Brufsky et al.[20] pro-studies,[17-22] improved outcomes were attempted and achieved invided education and performance feedback to physicians prospec-therapeutic situations where indisputable evidence existed to sup-tively regarding their patients who were receiving prescription H2-port the goals of clinical care and strategies proven to achievereceptor antagonists. The goal of the study was to move marketthem. Other common features of these studies include the interdis-share to cimetidine from other H2-receptor antagonists (e.g. famo-ciplinary approaches used to achieve improved outcomes.tidine and ranitidine). The market share of cimetidine was in-

creased by 53.8% and was associated with a cost savings of The fact that these improvements occurred in managed care$US1.06 million. In the second trial, a retrospective evaluation by environments does not make them unique, as much as it makes theAndrade et al.,[19] showed that the implementation of a switch problems addressed common. One of the benefits afforded byprogram to convert prescription H2-receptor antagonists to over- managed care is the availability of large relational claimsthe-counter (OTC) versions of the same medication successfully databases that allow the exploration of approaches to improvingreduced the number of prescriptions by a factor of 1.5 without care. Furthermore, the mandate for healthcare quality from pur-increasing the number of physician visits. While the study design chasers coupled with the standards and measures supported by thehas limitations because it is retrospective, the use of pharmacy US National Council on Health Care Quality, has led to renewedclaims data reduces the likelihood of selection bias and provides a impetus to reduce overuse, misuse and underuse of healthcarereliable assessment of drugs dispensed. In both of these studies the resources including prescription drugs.

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

152 Czubak et al.

2. Factors Influencing the Prescribing 1996 and 2001, reaching $US2.8 billion.[31] DTC advertising is aof Medications marketing strategy used to complement promotional efforts

targeted to professionals.[32]

Increased spending on prescription drugs has been attributed toSome critics of DTC advertising view it as a stimulus thatseveral factors, which include an aging population, the availability

encourages healthy people to believe they need medical attention,of diagnostic technology, a broader coverage of drugs in health-the negative consequence of which has been coined ‘medicaliza-care insurance plans, newer high-priced drugs and increased con-tion’,[33] i.e. non-medical problems become defined and treated assumer demand exaggerated by direct-to-consumer (DTC) adver-medical problems. It has been suggested that manufacturers deter-tising.[25,26] All have resulted in increased prescription utilizationmine whether a DTC campaign for a particular agent will beas reflected in more days of therapy per user and more users.pursued by estimating the level of persuasibility among doctors.[33]

Higher prescription utilization has heightened the potential forOne study concluded that despite the fact that physicians claimeddrug-related problems.to be ambivalent towards therapy that was requested by patients, inmost cases physicians did prescribe the requested medication.2.1 Aging PopulationThus, the demands of patients who are exposed to DTC advertis-

It is estimated that the growth in the number of Americans aged ing may be associated with inappropriate prescribing decisions.[34]

>65 years will double from 35 million to 70 million by 2030, along When consumers receive poor quality healthcare information orwith an exponential increase in the number of adults aged ≥85 misinterpret information from advertisements, healthcare out-years.[27] Innovative medical technology and the discovery of new comes can be impacted negatively. Valuable practice time ispharmaceutical agents have improved a patient’s quality of life wasted when physicians must explain why a particular therapy isand led to increased levels of functioning for many US patients inappropriate or unnecessary.[34] Physicians are not blameless aswith chronic medical conditions. Many of these patients are elder- they consistently overestimate patients’ expectations and underes-ly individuals, 90% of whom fill at least one prescription during a timate the cost of medications.[35] Proponents of DTC advertisingyear.[27] On average, elderly Americans with prescription drug and Internet access to medical information argue that health litera-coverage consume multiple medications for more than four condi- cy has been improved by wider availability of information totions per year. Often, the prescriptions that are filled are for the patients.newest and most expensive drugs.[28] The correlation between ageand prescription utilization is evidence of the challenge facing

2.4 Adverse Effects of Medicationsprivate healthcare plans and the federal government who arecharged with the task of providing prescription drug coverage to

Suboptimal prescribing, which may lead to suboptimal out-the growing number of elderly Americans over the coming years.comes, can occur when an adverse drug reaction is misinterpreted

2.2 Availability of Healthcare Information as a new medical condition, and an additional medication is thenprescribed to treat the adverse drug reaction. The new drug places

Increased prescription drug utilization can be linked to thethe patient at risk of developing additional adverse effects.[36]

increased availability of healthcare information.[26] The InternetIncorrectly prescribed therapies can lead to medication misadven-

has become an endless portal of healthcare information. In 2000,tures, such as the failure of a therapeutic agent to produce the

of the 52 million American adults who sought healthcare informa-intended outcome. Medication misadventures can result in mor-

tion, 21 million found it on the Internet.[28] Access to healthcarebidity and mortality that is preventable.[37] Studies have been

information has grown within public and health-science librar-conducted in an attempt to identify the potential for drug-related

ies.[29] This information wave has led to the evolution of themorbidity and mortality.[38-40] In 1996, it was estimated that

‘consumer specialist’.[30]

21.3%, or more than one in five, of elderly Americans in thecommunity setting used at least 1 of 33 drugs identified as being

2.3 Direct-to-Consumer Advertisinginappropriate for use in geriatric patients.[41] The propensity forthis inappropriate prescribing to result in morbidity and mortalityPatient demand for newer, more expensive medication can behas not been evaluated. However, hospitalization rates have beenattributed to aggressive DTC advertising that began in 1997, withshown to increase as a result of medication noncompliance andthe release of the US FDA’s guidelines regarding advertising toadverse drug effects. In 2000, drug-related morbidity and mor-consumers through electronic media.[26] In the US, annual spend-tality in the US was estimated to cost $US172 billion.[9]ing on DTC advertising for prescription drugs tripled between

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care 153

Researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, portion of which is their condition. However, a substantial burdenMassachusetts, USA concluded that adverse events caused by of illness is associated with medical error, cost, rework, andmedications are frequent.[38] Using a computerized search program complexity of the healthcare system. Excessive cost of medicationto detect incidences of adverse drug events, researchers found an or medication co-payments contributes to the burden of illness andadverse drug event rate of 5.5 per 100 outpatients who presented can lead to non-adherence and failure to achieve the desiredfor care, which is similar to the rates reported in hospitals of 2 per outcomes.100 admissions to as high as 7 per 100 admissions. Among adverse

3.2 Education by Academic Detailingdrug events, 23% were life-threatening or serious and 38% werejudged preventable. Hospitalization was required in 9.1% of ad-

A physician may write a drug prescription to end a difficultverse drug events.patient consultation.[45] Inappropriate prescribing may occurIn 2001, results from a study conducted in an integrated health-through habitual prescribing rather than through an active prob-care network found that 3.2% of hospital admissions were causedlem-solving approach.[45] Through active detailing, physicians canby adverse drug events and 76% of them were preventable.[39]

be equipped with unbiased, quality, patient-targeted information.A meta-analysis suggests that more than 1 million outpatients

Academic detailing strategies are best individualized to accommo-in the US experienced an adverse event that required admission to

date physicians’ behavioral styles, their perspective along thethe hospital in a year.[40] Furthermore, 4.7% of all annual hospital

continuum of change, and their individual pattern of adoption (i.e.admissions were caused by drugs.

how fast an individual incorporates knowledge into behavioralchange).[46-48] Incorporating this knowledge into the development3. Improving Prescribing Practicesof educational outreach programs and collaborative practice envi-ronments may yield higher physician acceptance.

3.1 Private Sector The American Medical Association[49] and the US Pharmaceu-tical Manufacturers Association[50] recently released revised stan-

The benefits of improving prescribing patterns in the private dards, which provides a guideline for the rights and responsibili-sector can be viewed on a large scale by considering third party ties of physicians and pharmaceutical representatives when engag-insurers, employers, and payers, or on a small scale, by consider- ing in educational activities. These guidelines are expected toing healthcare providers and patients. Often the benefits are ac- decrease the number of social outings, gifts, and trips that maycrued from both perspectives. unduly bias physician prescribing. However, it is too early to

The large-scale benefits include reduction in costs and im- determine the impact of the guidelines on drug prescribing pat-provements in quality indicators. A reduction in cost associated terns.with decreased medication consumption is realized by healthcareplans that are at financial risk for the members they insure.[42]

4. Evolution of a Strategic Framework for ProvidingThese savings may or may not be passed on to employer groups as Quality Healthcarethey may be translated into dividends used to cover additionalmedical benefits. Patients with prescription drug coverage are In the 1980s the US government and large employer groupsrelatively insulated from the costs of medication as they contribute relied heavily on HMOs to develop solutions to slow the rate ofonly the required co-payments. Physicians are often unfamiliar rising healthcare cost inflation. HMOs responded by focusing onwith the costs of prescription medications.[43] As employers seek individual delivery components of the healthcare system, such asto do business with healthcare plans that meet or exceed industry reducing hospitalization rates and regulating physician reimburse-standards in providing quality healthcare, achieving optimal out- ment.[51] This fragmented approach was not able to slow the risingcomes with the appropriate use of medications equates to addition- costs of healthcare. Too much emphasis was being placed on costal payor benefit.[44] alone instead of the quality of care.

Healthcare providers and patients appreciate benefits such as Case management programs were developed out of the effortsimproved quality and safety of the medication use process, the to provide quality care while reducing healthcare costs. With thisenhanced efficiency of the delivery of medication information approach, case managers were assigned to individual patients withfrom healthcare providers to patients, and the opportunity to high-cost or complex medical conditions. The case managers,strengthen the patient-provider relationship emphasizing the im- usually nurses, became involved in all aspects of the patient’s careportance of the patient perspective. A goal of all healthcare provi- and coordinated their efforts with physicians to develop a careders and institutions is to reduce the patient’s burden of illness, a plan. However, these programs proved to be more expensive over

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

154 Czubak et al.

the long term and were focused on the care of individual patients tensively advertised by a healthcare plan, may even attract morerather than on an entire population.[52] chronically ill patients to the program than anticipated, negating

any potential cost savings.[55] Furthermore, enrolling patients in aBy the 1990s, the focus shifted to population-based approachesdifferent program for each chronic illness can disrupt the continu-of reducing cost and maintaining quality care for patients withum of care between the patient and their primary care physician.[51]chronic illnesses (table III). One such approach is disease manage-Patients may change healthcare plans several times throughoutment. This concept was pioneered by the pharmaceutical industrytheir lifetime which can also disrupt the continuum. Several inte-as a means to maintain a positive relationship with HMOs, at agrated healthcare systems, such as the Henry Ford Health System,time when most HMOs were determined to decrease the amounthave tried to maintain this balance by providing disease manage-they paid for prescription drugs. Many pharmaceutical companiesment programs to enrolled patients.sold these programs as ‘value-added’ services to the HMO. The

The current healthcare system in the US is designed to focus onpharmaceutical industry uses disease management programs totreating patients with acute illnesses rather than patients requiringincrease product sales by gaining access to the HMO’s formularylong-term care for chronic conditions. With the advent of theand to identify non-adherent patients. The involvement of the drugHMO, primary care physicians have become the ‘gatekeepers’ tocompanies with the physician for disease management purposesspecialty care, laboratory and radiology services.[56] Primary carealso provides access for product detailing.[53]

physicians are expected to coordinate all aspects of patient care,Most disease management programs focus on conditions ofwhich has become increasingly difficult as the number of patientshigh prevalence, with high treatment cost, and those susceptible tothey are expected to treat continues to rise. Time constraints of thepractice variability. Disease management programs rely on evi-shortened office visit often lead to dissatisfaction for the physiciandence-based guidelines with interventions proven to improve pa-and patient. The physician may not be able to adequately addresstient outcomes.[54] Hundreds of disease management programseach chronic condition for patients with multiple chronic condi-exist, including those for chronic conditions such as diabetestions. For example, it is not uncommon for a patient with diabetesmellitus, asthma, heart disease, and hypertension. Disease man-mellitus to also have coronary artery disease and hypertension, allagement programs have been effective as a means to identifyrequiring intensive medical management, drug therapy regimens,patients with chronic illnesses and offer them educational servicesand laboratory monitoring. Without the support of a motivatedabout their conditions and medications; however, the return onpatient, it is difficult for the physician to make significant im-investment has been questioned.[51]

provements in the patient’s health during the course of a chronicSeveral problems with the disease management approach havecondition.been identified. Programs offered by the pharmaceutical industry

Several innovative ideas have been proposed to allow for themay be somewhat biased. An example is when the pharmaceuticalprovision of quality healthcare to patients with chronic conditions,industry promotes their own products as first-line therapy insteaddespite the challenges posed within the current healthcare system.of diet and exercise, or promotes a brand-name product when aThese ideas include working in primary care teams, providinggeneric is available.[53] Disease management programs, when ex-same day appointment scheduling, setting collaborative goals withpatients, treating patients during group visits, shifting to an elec-tronic medical record and adopting the chronic care model devel-oped by Bodenheimer.[56]

5. Chronic Care Model: Changing Care Delivery

The chronic care model integrates all aspects of chronic illness,from the community, organization, physician, and patientlevels.[57] This model seeks to encourage the patient to take onresponsibility for their care, while seeking help from an educatedand motivated healthcare team. Within the chronic care modelthere are six components identified to implement this approachwithin the community, the healthcare system, and the providerorganization. These components include: community resourcesand policies, healthcare organization, self-management support,

Table III. Evolution of the strategic framework for optimizing drug therapyoutcomes

Period Strategy Features

1980–1990 Drug focus Choices of medications within drugclasses; drugs blamed for pooroutcome

1990–2000 Disease focus High-cost, prevalent diseases;drug classes involved in diseasetreatment; disease or physicianblamed for poor outcome

1995–present Patient focus High-cost, complex-care patients;patient or physician blamed forpoor outcome

2000–present Chronic care System of providing care;focus; disease blameless cultureprevention

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care 155

delivery system design, decision support, and clinical information lower co-payment to the patient, usually $US10–15 for a month’ssystems.[57] These components are discussed briefly in this section supply of the medication.as they relate to the experience of implementing aspects of the The Henry Ford Health System has promoted formulary adher-chronic care model at the Henry Ford Health System and other ence through several mechanisms. The co-payment is lower if thehealthcare systems with the goal of managing pharmacy outcomes. patient requests to fill a generic medication. Physicians and pa-

tients are educated about the value of generic medications withacademic detailing, brochures, and television public service an-5.1 Community Resources and Policiesnouncements. When a patient chooses to fill a drug that is not onthe formulary, they are then forced to share in paying for the costProviding support to patients with chronic illnesses outside ofof the drug by paying a higher co-payment. Step-care protocols arethe primary care office is an important part of the continuum ofdesigned to prevent the use of more expensive agents as first-linecare. It is necessary for the primary care physician to have addi-therapy, by requiring prescribers to follow a step guideline of non-tional resources available in his or her community for chronicallypharmacologic and prescription treatment options. Quantity limi-ill patients, especially if the physician is not part of a largertations include restricting greater than a month’s supply for mosthealthcare system. These resources include nutritional and dietarydrugs or imposing a specific limit on the number of doses basedcounseling, exercise and weight loss programs, behavioral supportupon a clinically accepted duration of treatment. Prior authoriza-groups, and individual case managers.[57] By encouraging the usetions restrict the use of expensive, complex, or non-formularyof outside resources, the physician motivates the patient to becomedrugs by requiring the prescriber to seek the approval of the payermore active in their own care while at the same time offers servicesfor coverage based upon criteria evaluating the safety and efficacythat may otherwise not be available at the office visit.of the drug along with the individual circumstances affecting thepatient.5.2 Formulary Management

The goals of the healthcare delivery systems and the healthcare 5.3 Evidence of Effectiveness in Reducing Costteam need to become aligned in order to ensure that these pro-grams are viable and can continue uninterrupted over a patient’s The effectiveness of interventions in decreasing drug costs haslifetime. Most healthcare organizations have adopted integrated not been studied widely in the literature. A retrospective studyinpatient and outpatient formularies or a specific listing of drugs conducted by Joyce et al.[59] examined claims data of patients agedand devices that are preferred by the delivery system based upon 18–64 years to determine how multi-tier formularies and manda-their safety, efficacy, and cost data. Each new drug or drug class tory generic substitution influence costs to the payer and patientthat enters the market is reviewed by the healthcare organization’s for outpatient drugs. The study found that the cost of drug expendi-pharmacy and therapeutics committee, usually composed of a tures for the healthcare plan could be significantly reduced bygroup of physicians, pharmacists, and nurses. Decisions on wheth- requiring mandatory generic substitutions, introducing an addi-er to include a drug onto the formulary are based on multiple tional co-payment level, or increasing existing co-paymentfactors. These include reviewing peer-reviewed medical literature, amounts or percent co-insurance rates paid by the patient. How-clinical practice guidelines, comparative safety and efficacy infor- ever, the overall reduction in spending on drugs was of greatermation of other drugs, patient compliance, drug interactions, ad- benefit to the healthcare plan since the patient was often burdenedverse drug events, and potential cost savings.[58] Managing the with increased cost sharing by have to pay more for out-of-pocketpharmacy formulary can become a daunting task as a number of expenses.new medications are being introduced into the market including In a literature review, Carroll[60] evaluated peer-reviewed clin-combination drug products, multiple drugs within a drug class, and ical studies to determine the way in which effective MCOs usebiologic agents with unique mechanisms of action. formularies, therapeutic interchange programs, and prior authori-

Formularies have become increasingly complex over the years zation protocols to change prescribing and dispensing behaviors.and several different methods have been developed to maintain the This review concluded that few studies have examined the impacteffectiveness of the formulary as well as patient and provider of open formularies on behavior, and yet studies assessing the usesatisfaction. Formulary management has been improved by utiliz- of closed or more restrictive formularies have produced conflict-ing multi-tier benefit designs, step-care protocols, and prior au- ing results. According to the review by Carroll[60] most studiesthorization protocols. Multi-tier benefits allow the healthcare or- have shown that an increase in formulary restrictiveness will lowerganization to promote its preferred formulary drugs by charging a the utilization rate of drugs or related non-formulary products,

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

156 Czubak et al.

however, some studies have also shown an increase in utilization as well as their peers, as a means of continuously monitoringrates. Therapeutic interchange programs, which allow pharmacists prescribing behaviors and providing clinician feedback. Compara-to dispense a therapeutically equivalent product with a different tive data are an effective tool for identifying discrepancies inchemical. Only four published studies evaluating prior authoriza- clinician prescribing behavior for clinical policies or utilizationtions were identified by Carroll, who concluded that prior authori- goals.[63]

zations were effective at reducing costs,[60] but the results may not Within the Henry Ford Health System, adherence to the form-be generalizable since they focused specifically on NSAID and ulary is managed by clinical pharmacists. The pharmacists meetbenzodiazepine drug classes. Both drug classes include generic with physicians on a quarterly basis to review their prescribingalternatives and most patients taking these drugs have mild or performances. The physicians are provided with prescribing datamoderate symptoms which are unlikely to result in hospitaliza- presented to them on report cards. This allows the physicians totions or increased medical costs.[60] compare their prescribing habits to their peer group of physicians

Maintaining physician and patient satisfaction can also be and to see if they are meeting healthcare system goals. Thechallenging when managing a formulary. Effective formularies are pharmacist is then able to work with the physician to improve theirdynamic and always evolving. Patients and physicians may feel prescribing patterns. The pharmacists recommend strategies to thethat the formulary is too restrictive, especially when they must try physician to decrease overutilization of non-preferred productsmultiple drugs on the formulary in order to find a drug that is and antibacterials, increase the generic use rate, and promote cost-effective for treating the patient’s symptoms. Physicians and their saving alternatives to prescription drugs such as lifestyle modifica-support staff may feel burdened by added time constraints asso- tions and OTC drugs.ciated with filling out paperwork and additional telephone calls to A similar approach has been utilized by another large integratedcomplete multiple authorization requests. Patients may also be healthcare system in the US, Kaiser Permanente of California.[64]

reluctant to pay the higher co-payments that are instituted with Within this HMO, clinical pharmacists are trained to work as drugmore three-tier benefit designs. information coordinators to assist prescribers with adhering to the

A study conducted by Nair et al.[61] examined how two- and healthcare system’s formulary. These specially trained pharma-three-tiered pharmacy benefits affect members’ attitudes toward cists develop education programs on therapeutic interventions fortheir healthcare plan.[61] A survey was mailed to a sample of over appropriate cost-effective drug therapy. Each physician is also10 000 members who had at least one common chronic disease provided with data regarding their prescribing performance instate (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, gastroesophageal re- order to evaluate their own practice and compared their perform-flux disease, or arthritis) at a large managed care organization in ance with their peer group. However, this healthcare system isthe US with either a two or three-tiered pharmacy benefit plans. unique in that prescribers are authorized to use a non-formularyThe members responding to the survey were generally older, medication if the prescriber feels that it is clinically indicated,sicker, and filled more chronic medication prescriptions. The without requesting a prior authorization. These circumstancesresults of the survey found that members enrolled in a three-tier include known allergies, intolerance, or non-response to formularybenefit plan reported a lower satisfaction rate with their plan medications. Even though this approach appears to be less restric-compared with those in a two-tier plan. Members enrolled in two- tive, and ultimately leaves the choice of drug therapy to thetier plans were more likely to recommend their current healthcare judgment of the prescriber, Kaiser Permanente has a formularyplan to others and less likely to switch plans than those in three- compliance rate of approximately 98%.[64]

tiered plans. Members with increased cost sharing for their pre-scription benefits tended to have less favorable attitudes with 5.5 Self-Management Supportprescription coverage by their healthcare plan.[61] Three-tierpharmacy benefit designs can control drug costs and have not been The chronic care model encourages patients and their familyshown to increase the utilization of other medical resources such members to take an active part in their own healthcare since it isas physician office visits, hospitalizations, or emergency room the patients who must make daily decisions affecting their chronicvisits.[62]

illness. It is up to the patients as to whether or not they willexercise, what foods they will eat, and whether they will take their

5.4 Physician Report Cards medications as prescribed. The patients and their family memberscan be taught how to self-manage aspects of their illness with the

Pharmacy utilization reports are an important tool used in support and guidance of the healthcare team. The healthcare teamacademic detailing. Clinicians are benchmarked against standards, must first emphasize the role the patients play in the decision-

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care 157

making process. Then the team will need to assess the patients’ govern behavioral change with respect to how they deal with newown skills, confidence level, support systems, and the potential information.[45]

barriers to self-management before developing a patient specific The abundance of medical information, published in a varietycare plan with collaborative goals.[65] The patient specific care of mediums (such as medical journals, CD-ROMS, bulletins,plan needs to include realistic goals that the patient can achieve circulars, e-mails, professional discussion groups, videotapesand would be willing to work towards.[66] [both education and promotional], and the Internet), clinicians are

The self-management component of the chronic care model has becoming overwhelmed by the task of remaining current withbeen difficult to implement in the past since it requires the collabo- medical practice[67] and drug therapies.[68] If clinicians were sur-ration of healthcare providers and the development of evidence- veyed to find out what the barriers were to keeping up with newbased programs. Traditionally, programs with self-management medical information, time constraints would probably be the mostcomponents have been disease state focused, are of short-term frequently reported. They might be less inclined or even embar-duration, and are not aligned with the goals of the primary care rassed to admit that they have difficulty accessing, interpreting,team.[65] and applying current and correct information. The fact is, knowing

when to look for new evidence, where to locate it, and how toWhether self-management support programs have improvedevaluate, synthesize and apply it to a clinical situation is diffi-outcomes for patients with chronic conditions, such as asthma andcult.[69] Having too much, poorly organized information can leaddiabetes, was addressed by Bodenheimer et al.[66] These research-to decision errors.[68] Therefore, clinicians who lack adequateers conducted a literature evaluation of controlled clinical trialsmedical information skills or who rely on biased informationand identified 23 studies that measured outcomes related to im-sources may be more apt to make inappropriate prescribingprovements in lung function. An analysis of these studies revealedchoices because their perceptions of drug attributes are skewed.that there was a greater improvement in outcomes when action

plans were developed and utilized, especially for patients with To ensure that new practitioners are competent in using medicalmore severe forms of asthma. A secondary analysis of the litera- information resources, medical informatics is now emphasized inture was conducted to evaluate self-management teaching and undergraduate medical curricula. For those who have been practic-improvements in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.[66] Unfor- ing for years, continued medical education programs focused ontunately, very few of the studies in this secondary analysis includ- improving medical information skills are a necessity and health-ed teaching patients problem-solving skills and creating action care plans and organizations can benefit from promoting suchplans. Of the 46 studies found that measured the impact of patient programs.[67]

education and knowledge about diabetes, the reviewers found thatin 33 of the studies there was a positive benefit in improving 5.7 Practice Guidelinesglycemic control, the patient’s understanding about diabetes, and adecrease in cardiovascular risk factors.[66] The challenge of imple- The development of practice guidelines is another approachmenting self-management techniques in the primary care setting is taken by professional groups, scientific organizations, and regula-complicated by a lack of training of healthcare professionals, lack tory bodies to encourage evidence-based medical care. Guidelinesof acceptance of the patient as their own primary caregiver, and are general recommendations developed to help practitioners andfailure to receive reimbursement from third party payers, Medicare patients make informed healthcare decisions regarding certainand Medicaid.[66]

clinical circumstances. However, guidelines do not always resultin improved outcomes and cost reductions.

Comprehensive practice guidelines for the treatment of non-5.6 Abundance of New Drug Informationspecific upper respiratory tract infections were implemented atfour primary care clinics in a large HMO and its effect on theIf we consider the point of prescribing as the rate-limiting stepquality and cost of care was evaluated.[70] Patients diagnosed within prescription drug utilization, it becomes apparent that carefulnon-specific upper respiratory tract infections conditions wereattention should be given to influencing clinicians’ prescribingassessed by telephone and if appropriate, given treatment advicehabits and decisions. Long-lasting effects on prescribing practicesand instructed to visit their physician if their symptoms becamemay be achieved if the factors that contribute to a clinician’spersisted or became worse. The guideline discouraged initial anti-therapeutic decisions are considered when interventions are devel-bacterial therapy.oped. Perceived attributes of medications, sources of drug infor-

mation, the culture and policies of the system in which the clini- The investigators expected that use of the guidelines wouldcian practices, and the clinician’s own unique attitudes and beliefs reduce physician visits as well as the number of antibacterial

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

158 Czubak et al.

prescriptions written and therefore treatment costs would be re- patients admitted for AMI, 2409 pre-intervention (1992–1993)duced.[70] However, the number of physician visits within the and 2938 post-intervention (1995–1996) were included for treat-21-day period following initial contact increased from 54% prior ment selection performance analysis. The first intervention was ato the implementation of the guideline to 75% after the guidelines 1-day meeting of all of the opinion leaders to review the guideline,were adopted. There was a slight, insignificant increase in the confirm commitment to the program, and identify barriers toproportion of patients who received initial care by telephone after guideline adherence. After the meeting, the opinion leaders werethe guideline was implemented (from 45.5% to 47.2%). There was given tools such as slides with ‘talking points’, administrativea significant decrease in the number of initial antibacterial pre- support (i.e. meeting scheduling and producing discussion hand-scriptions written on the first day of contact with the clinic, which outs) and illustrated educational material. This printed materialwas a positive result. However, there was an increase in the covered the appropriate use of the targeted drugs and they werenumber of antibacterials prescribed during the 21-day period drafted, approved and edited by the opinion leaders. These toolsfollowing initial assessment. The rates were 44% during the pre- were used as part of the second phase of education, which involvedguideline period and 55% during the post-guideline period. The formal and informal consultations and meetings with physicians asimmediate reduction in antibacterial prescriptions, but similar well as activities to modify current clinical policies on the treat-cumulative antibacterial prescription rates over the 21-day post- ment for AMI.[72]

assessment period, demonstrated the inability of guidelines imple- As a result of the intervention, the use of β-adrenoceptormented in this manner to produce sustained changes in prescribing antagonists and aspirin significantly increased.[72] Among the ex-practices when used alone.[70] The study was an uncontrolled pre-/ perimental hospitals, aspirin use in the elderly increased by 17%post-evaluation and thus may have been subjected to bias.[48,71] compared with a decrease of 4% in the control group. β-Adre-The guideline may have failed because of ineffective guideline noceptor antagonist use increased in all of the hospitals (an in-implementation, the difference in time periods during which the crease of 63% for experimental hospitals and 30% for controls).two patient groups were treated (pre-guideline winter 1993, post- The authors concluded that national guidelines based on strongguideline winter 1994), and the lack of consideration of the evidence could be used to improve the quality of care whenpatients’ expectations for treatment. opinion leaders facilitated their acceptance amongst physicians.[72]

Cabana et al.[71] identified several specific barriers to guideline The study intervention evaluated by Soumerai et al.[72] wasadherence including lack of awareness that guidelines exist, unfa- effective because it encompassed various educational interven-miliarity with their content, lack of agreement with recommenda- tions including provider-targeted literature, formal educationaltions, lack of physician confidence in their ability to adhere with programs, outreach visits, (including academic detailing), localthe guideline, lack of confidence in the expected outcomes, no opinion leader influence, and provider audits with feedback. Thesemotivation to change practice, time limitations, guideline com- were all interventions identified as having positive effects whenplexity, patient preference, and unavailable resources. In order to used to change prescriber behavior by Davis and colleagues.[73]

improve guideline adherence, the barriers to adherence in a partic- Patient-mediated interventions and physician reminders were alsoular practice need to be identified initially. Once identified, inter- shown to be effective. The rate of positive behavioral changesventions targeting those specific barriers can be implemented as increased with the number of simultaneously employed interven-part of guideline education efforts. tions. When three or more interventions were used the rate of

Soumerai et al.[72] took a multifaceted approach to improving change was reported to be 79%.[73]

guideline adherence. He and his colleagues evaluated the effect The most effective single intervention was outreach visits,that local medical opinion leaders providing educational outreach including academic detailing activities.[73] The ease of implemen-and performance feedback would have on improving adherence to tation and proven efficacy of academic detailing has led to itsthe American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association popularity and frequent use in a variety of practice settings. Thisguidelines for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). intervention consists of repeated personal visits made by a utiliza-During the study the use of β-adrenoceptor antagonists in all tion manager that include feedback, clear and relevant practiceeligible patients, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) and thrombolytic recommendations, and suggestions for implementing new proce-agents in the elderly and reduced use of prophylactic lidocaine in dures. These outreach sessions can be conducted with individualall patients were measured to assess guideline adherence. clinicians or in small group settings. A randomized controlled trial

The study by Soumerai et al.[72] was a randomized controlled of 200 clinicians proved that both are effective.[74] In this trial,[74]

trial and was conducted at 37 hospitals (20 were experimental and pharmacists and general practitioners were randomized to receive17 acted as control hospitals) in Minnesota, USA. Data for all either an individual educational visit, a group visit or no visit at all

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

Optimizing Drug Prescribing in Managed Care 159

(control group). The aim of the educational visits was to raise 5.8 Solutions

clinician awareness regarding the anticholinergic adverse effectsof antidepressants and encourage the use of antidepressants with Strong leadership support is effective in changing prescribinglower anticholinergic properties. Prescribing rates of highly anti- behavior because physicians look to others in their field who theycholinergic antidepressants were reduced by 30% after two indi- respect to clarify the benefits of new therapies, and peer pressurevidual visits and by 40% after two group visits. Compared with the leads to faster practice changes in a closely knit environment.[77]

control group, the decrease associated with both interventions The closely knit association of physicians employed by the healthcombined and for the group visit intervention was significant. The system and the respect that local opinion leaders command

amongst network providers should be leveraged when initiativesauthors concluded that both methods were effective and that groupto promote preferred drug use and appropriate prescribing within aapproaches would likely be useful and cost effective.[74]

healthcare plan are developed.The least effective educational strategies were short programsAn unpublished example of an educational intervention at thewhich generally resulted in no change at all.[73] In one study,

Henry Ford Health System combining academic detailing andinvestigators compared strategies to improve compliance withphysician prescribing is the use of antibacterials for upper respira-National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel (NCEP)tory infection. An example of a physician’s utilization report isguidelines.[75] This randomized controlled trial was conducted inshown in table IV. This clinician’s rate of antibacterial prescrip-an urban teaching hospital. The physicians included in the studytions per member per month exceeded that which was expected

were second- and third-year medical residents seeing patients inand acceptable by 10% and he/she was therefore identified as an

outpatient clinics. Over a 5-week period, one of the interventionoutlier prescriber requiring educational intervention. His/her aver-

groups attended a lecture and received generic chart reminders ofage cost per antibacterial prescription also exceeded the acceptable

the NCEP guideline recommendations on each eligible patient’slimit, signaling that higher cost non-preferred agents are being

chart. The second intervention group attended the lecture andprescribed.

received patient-specific information regarding recent laboratoryDuring the academic detailing session a utilization manager can

results along with treatment recommendations immediately beforefocus on appropriate indications for antibacterials using tools such

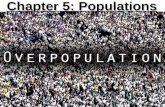

patient consultations. The control group attended a lecture only.as the upper respiratory infection treatment algorithm (figure 1).

Guideline compliance rates improved within the two intervention Appropriate situations for antibacterial use can be discussed withgroups, but not in the control group.[75]

reinforcement of the treatments of choice as narrow spectrum,Another study attempted to assess factors that may influence low-cost generic antibacterials. To further reinforce the message

NCEP guideline adherence by randomizing primary care physi- of appropriate prescribing, patient education with brochures orcians from 174 practice sites to receive offers to either (i) attend a audio-visual displays can be effective.3-hour seminar on high cholesterol; (ii) in addition to the 3-hour Combining multiple educational interventions, as suggested inseminar, attend follow-up seminars and receive free office materi- the previous example, demonstrated success when evaluated byal; or (iii) receive no education (control group).[76] After 18 Gonzalez et al.[17] The approach was a well designed, effectivelymonths, no significant differences in cholesterol screening rates or implemented, multidimensional intervention to reduce antibacteri-compliance with the NCEP guidelines were seen between the al therapy in patients with acute bronchitis. Two levels of interven-intervention groups and the control group. tion were implemented at selected clinics to decrease antibacterial

Table IV. Example of a specified antibacterial report by a primary care provider during a period of 1 month

Prescribing Specialty Prescriptions written for patients on the doctor’s panela Prescriptions written by specific physician

characteristics no. of panel no. of cost per no. of total no. of cost perprescriptions total prescriptions member prescriptions paid prescriptions member

paid ($US) per member per ($US) per member perper month month ($US) per month month ($US)

Actual Pediatrics 59 1923.71 0.1 3.28 58 2606.63 0.1 4.44

Expectedb <0.06 <1.05 <0.04 <0.90

a Prescriptions may be written by specific physician or other physicians.

b Goals were set by examining appropriateness of prescriptions to determine that they were linked to volume and cost/member. Prescribersachieving >0.06 prescriptions per member or >$US1.05 per member are more likely to prescribe antibacterials inappropriately.

© 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2004; 12 (3)

160 Czubak et al.

No underlying factors• Fluids (vaporizer)• Rest• Doxycycline 100mg every 12h for 10 days or• Clarithromycin 500mg every 12h for 10 days

Upper respiratory infection/pharyngitis

Acute bronchitis Community-acquired pneumonia

Cough up to 14 daysFever/chills for 72hSinus x-ray may show opacityPurulenta rhinitisSore throat up to 5 days

Coughb up to 3 weeksFever/chills for 72hNegative chest x-rayPurulenta phlegmIncreased dyspnea

Persistent coughChronic bronchitisNegative chest x-rayPurulenta phlegmIncrease dyspnea, coughIncreased sputum volume

CoughFever and chills for 72hAbnormal chest x-rayPurulenta sputumDyspnea, tachypneaAbnormal breath sounds, crackles

Treatment Treatment Treatment Treatment• Fluids (vaporizer)• Rest• Antipyretics• Decongestants• Antitussives• No antibacterials

• Fluids (vaporizer)• Rest• Antipyretics/analgesics• Antitussives• Short-acting β-adrenoceptor agonists (if wheezy)• No antibacterials

Mild disease• Fluids (vaporizer)• Rest• Short-acting β-adrenoceptor agonistsModerate disease• Add oral corticosteroids• O2 as required• Doxycycline 100mg every 12h for 10 days or• Clarithromycin 500mg every 12h for 10 days (evidence supporting antibacterials is weak)

Underlying factors• Fluids (vaporizer)• Rest• Levaquin 500 mg/day for 10 days or• Other supportive therapy as needed

Acute exacerbation ofchronic bronchitis

Fig. 1. Guidelines for the management of upper respiratory infection treatment. These guidelines should be considered general recommendations for theconditions described. The best treatment for an individual may vary based on their clinical presentation. a Sputum color does not denote bacterial infection.b Consider pertussis when cough lasts >2 weeks. Recommendations were derived from Bach et al.,[78] American Thoracic Society,[79] Sinus and AllergyHealth Partnership,[80] and Bisno et al.[81]

use for uncomplicated acute bronchitis. All patients at the full therapeutic regimens during or before office visits and makeimmediate recommendations.intervention sites received educational mailers in addition to of-

fice-based education materials that they received if they presented Pharmacist-managed medication management clinics and con-with bronchitic symptoms. The full intervention included periodic sultative services have demonstrated success in reducing prescrib-education sessions and practice feedback provided to clinicians ing inappropriateness and saving costs.[82,83] Significant reductionsduring staff meetings facilitated by clinic medical directors. The in the rate of inappropriate prescribing among patients aged >65limited intervention consisted of office-based educational materi- years were seen when the effects of clinical pharmacists providing

pharmaceutical care were evaluated during a randomized, control-als provided to patients, but no education intervention was pro-led trial including 208 patients who were recipients of polyphar-vided to clinicians. The effect of these interventions was comparedmacy.[82] Polypharmacy was defined as more than or equal to fivewith control sites that did not receive any additional education,chronic medications per patient. This study by Hanlon et al.[82]

similar to usual care. Antibacterial prescription rates for 2027took place in a general medicine clinic at the Veterans Affairsadults were included in the final analysis. The full intervention siteMedical Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. A clinical phar-demonstrated a substantial decrease in antibacterial prescribing formacist reviewed the patient’s drug regimens, met with them tobronchitis, i.e. from 74% to 48%. No significant changes indiscuss their therapy, and made recommendations to both the

antibacterial prescribing were seen in the limited interventionpatient and their physician. The primary study measure was the

(slight, nonsignificant reduction from 82% to 77%) or control sitesinappropriate prescribing score for each drug regimen as deter-

(slight, nonsignificant reduction from 78% to 76%). The limita- mined by the clinical pharmacist. After 3 months of the interven-tions of the study include a lack of a randomization process and tion, the inappropriate prescribing score in the intervention groupexclusion of antibacterial prescriptions filled at non-HMO affiliat- decreased by 24%, compared with a 6% decrease in the controled pharmacies. Successful reduction in antibacterial use required group. This improvement in prescribing was sustained 1 year afteran initial assessment of factors influencing patients’ and physi- the study was completed.[82] The magnitude of this interventioncians’ beliefs about antibacterial treatment, and carefully devel- was reported by the investigators to be similar to the effectsoped interventions aimed at changing each of those perceptions.[17] achieved when an academic detailing program was implemented

at a nursing home to improve psychoactive drug prescribing.[74]Academic detailing and utilization management techniques are

most often implemented retrospectively, after inappropriate be- In a study by Borgsdorf et al.[83] (similar to that of Hanlon ethavior is identified. A more proactive approach to changing pre- al.[82] in that it investigated pharmacist-managed interventions) a

total healthcare cost savings of $US644 per patient per year wasscribing behavior and educating clinicians is to screen patient’s