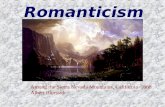

Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California (1868) by Albert Bierstadt.

On the Merced River, Albert Bierstadt. COURTESY OF THE ...Ed Ruscha, who began exploring the...

Transcript of On the Merced River, Albert Bierstadt. COURTESY OF THE ...Ed Ruscha, who began exploring the...

On the Merced River, Albert Bierstadt. COURTESY OF THE CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY.

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

amy scott

Twenty-First-CenturySublime

Nature and culture entangled

‘‘The word ‘nature’ is a notorious semantic and metaphysical trap.’’

—Leo Marx1

T ension between the desire to experience nature in its unadulterated form and

the urge to exploit it for material gain has long been at the center of landscape

painting in the American West. This is especially true in California, where

spectacular examples of both natural and built environments often exist in close

temporal and geographic proximity. Here, you can begin your day on a remote stretch

of the Pacific coast and within the hour be watching Chinese shipping containers

unload in the Port of Los Angeles; you can take in the sunrise over suburban San

Fernando Valley and the sunset in Yosemite National Park.

The connection between these places is as much about the conceptual as it is

the geographical, however. Whereas nineteenth-century artists projected visions of

the ‘‘Golden State’’ as a faraway place flush with natural resources, California’s

landscape today is less exotic and more closely entwined with human industry. Yet

far from rendering previous methods of depicting the landscape obsolete, contem-

porary artists are using historical practices and conventions to convey contemporary

experience. The influence of the classic California landscape has not waned, but

rather evolved.

BOOM | F A L L 2 0 1 4 29

BOOM: The Journal of California, Vol. 4, Number 3, pps 28–35, ISSN 2153-8018, electronic ISSN 2153-764X.

© 2014 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for

permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s Rights and

Permissions website, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp. DOI: 10.1525/boom.2014.4.3.28.

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

Of the traditional methods for representing California’s

natural environment, perhaps none has enjoyed more stay-

ing power than the sublime. This is due in part to the mul-

tivalent, flexible nature of the concept itself. The American

sublime emerged in the late eighteenth century but under-

went a significant transformation in response to the open-

ing of western lands following the Civil War. What once

represented a fear of the unknown became a more distinctly

market-based interest in expansion. Shifting the mood of

landscape art away from a solemn meditation on nature’s

mystery to a more passive contemplation of its development

potential, the New York–based painter Albert Bierstadt

asked his audience not to fear the wilderness but to look

hopefully toward a bicoastal future.2 Indeed, paintings such

as On the Merced River rejected metaphysical interpretations

of nature in favor of the rationalist logic of survey science

(Bierstadt accompanied the Lander Survey to the Rocky

Mountains in 1859) and thus encouraged a more tangible

connection to the West as a place. This is reflected in Bier-

stadt’s work both in the easy visual access he provides to

deep space as well as in his tightly painted foreground

fauna, which caused critics to marvel.

As Bierstadt’s career suggests, the sublime is not a fixed

concept but one that draws upon contemporary ideas of

nature to respond to external changes—including develop-

ments in technology—that shape the ways in which we

imagine both the natural and the built environment in rela-

tion to ourselves. An aesthetic formula designed to elicit an

emotional response to an apparently natural vision, the sub-

lime has been reconfigured in the postmodern era as

a means of naturalizing the presence of technology within

the contemporary landscape. Consider, for example, the

aesthetic proximity between Bierstadt’s version of Yosemite

and Michael Light’s large-scale photographs of San Pedro.

The former is a preindustrial ideal, the latter a fully realized

commercial setting dominated by the machinery of interna-

tional shipping. Both evoke an ambitious sense of scale

drawn from singular vantage points: Bierstadt’s oft-used

magisterial view and Light’s aerial perspective; both use

receding diagonals to create a sense of deep space and visual

command; both are cleared of human presence, reinforcing

the independent nature of the systems at work within them.

Painted shortly after the close of the Civil War, Bierstadt’s

On the Merced River anticipates California’s future as the

gateway to Pan-Pacific commerce. Light’s San Pedro fully

consummates that vision by the shipping containers stretch-

ing endlessly toward the horizon.

The technological continuum between Bierstadt’s Yose-

mite and Light’s San Pedro, between the Romantic era and

today, is more than superficial. In Bierstadt’s painting,

technology—though not visible—is implied throughout

the composition. Survey science is there, in the carefully

painted, highly detailed foreground topography. A sense of

materialism and accumulation is there, too, in the vignette

of natural wonders on display, especially the ample timber

supplies represented by the forest. Although Bierstadt does

not directly reference the coming industrial landscape,

he nevertheless anticipates it. In its perfectly ordered scene

of natural abundance, his On the Merced River speaks

powerfully to nationalist expectations of postwar economic

growth and progress.

Light’s San Pedro shares this sense of mastery over the

natural world and a seemingly unshakeable faith in America

as a geopolitical powerhouse. There is, however, a darker

aspect to the fully realized technocratic state as depicted in

Light’s work. In his San Pedro, one of several photographs of

the Port of Los Angeles bound together in an oversize folio,

a literal sea of commodities expands across the image,

bleeding past its borders. Visually organized by its dense

grid of intersecting lines, the photograph combines the real-

ism of immense amounts of surface detail with the aerial,

all-encompassing perspective of the map. Light requires not

only a wide-angle lens but also a plane to produce these

photographs (Light has had his pilot’s license since age

sixteen)—images that elicit a sense of wonder in the face

of a totalizing spectacle of technologic power, a ‘‘techno-

euphoria,’’ as some scholars have called it.3

Light’s visual embrace of heavy industry is intended to be

both awesome and beautiful. Yet for all the dynamics of order

and control that pervade his technocratic landscapes, they

also resonate with an element of ‘‘terror at the power and

progress of industrialization,’’4 in which the scales threaten

to tip from order to the chaos of industry run amok.5 This

element of anxiety or dread aligns Light not with Bierstadt,

but with the earlier, ‘‘Gothic’’ sublime popular with American

painters prior to the 1850s. It also sets him apart from some

of his contemporaries, including the decidedly un-sublime

Ed Ruscha, who began exploring the sameness of Los

Angeles during the 1960s. Working from a viewpoint sunk

deep within the city, Ruscha’s series, such as Some Los Angeles

30 B O O M C A L I F O R N I A . C O M

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

Apartments and Every Building on the Sunset Strip, chronicles

the experience of Los Angeles as an unending sequence of

buildings, each as undistinguished as the last. Archival in

their objective cataloguing and emotionally unresponsive to

their subject, Ruscha’s photographic series take no interest in

the sense of wonder that so awed his predecessors.6

Between the clinical objectivity of Ruscha’s series and the

frightening beauty of Light’s industrial San Pedro are a con-

tingent of artists who see the sublime more as the product of

a precarious balance between the awesome side of infrastruc-

ture and its threat to overrun the environment all together.

James Doolin’s Bridges, for example, uses compositional

Rancho San Pedro 04.28.06: Evergreen Container Terminal Looking Southeast, Terminal Island; Exxon Mobil Facility At Left, Michael Light.

COURTESY OF THE AUTRY NATIONAL CENTER, LOS ANGELES.

BOOM | F A L L 2 0 1 4 31

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

devices drawn from the Romantic-era sublime to affect

a sense of industry on an overwhelming scale. From a mon-

ocular perspective, the viewer takes in a breathtaking array of

industrial and natural features, from the majestic arc of the

overhead walkway to the elegant lines of the exit ramp and

multiple freeways converging in the distance. These encircle

other, more classic landscape elements including a placid

body of water, the Los Angeles River—itself only part-natu-

ral—crossed with train tracks, and distant mountains

enshrouded in an atmospheric haze common to both histor-

ical landscape painting and the Los Angeles skyline. How-

ever, if the painting outwardly celebrates the beauty of

industrial design, Doolin also conveys a sense of alienation

between the city and its human population. Cars with unseen

drivers move like automatons; graffiti—undesirable mark-

ings made by people no longer present—covers the

foreground; and a single tiny figure in the center of the paint-

ing trudges into the distance, his back to the viewer.

The scale differential between the human, the organic,

and the industrial components of Doolin’s Los Angeles sug-

gests a place where the natural and the manmade land-

scapes are deeply entangled. This nature-meets-culture

dynamic—in which the interstices between the two are

a valid subject in and of itself—is the focus of photographer

Karen Halverson, whose panoramic Mulholland Drive series

explores the ways in which these elements can work as

seamless extensions of one another. In Above Universal City,

for example, the curve of the guardrail echoes the hillside,

which gives way to clusters of thickly grown brush. Lush and

verdant, the dense tangle of flora is lit by an artificial glare (a

streetlight or camera flash), which reveals an abundance of

visual detail not unlike the topographic elements found in

Bridges, James Doolin. COURTESY OF THE ESTATE OF JAMES DOOLIN AND KOPLIN DEL RIO GALLERY.

Detail from Every Building on the Sunset Strip, Ed Ruscha, ©Ed Ruscha. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GAGOSIAN GALLERY.

BOOM | F A L L 2 0 1 4 33

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

Romantic-era painting. Both are designed to lure the viewer

in before giving way to a deep recession of space.

Mulholland Drive—which meanders through some of Los

Angeles’s toniest neighborhoods offering breathtaking views

of the city below—is in itself emblematic of the ways in which

feats of technology and engineering have transformed the

experience of the natural in the city. The road was cut through

twenty-two miles of hillside, which clearly entailed a massive

reworking of the natural environment. The construction

engineer, David Raeburn, described how the road was

designed with an awe-inspiring scenic experience in mind:

‘‘In driving over the completed portion of the highway,

one is charmed and amazed at the wonderful view of

the surrounding country, which is continually changing as

the vision sweeps from one side of the summit to the other.

The Mulholland Highway is destined to be the heaviest

travelled and one of the best-known scenic roads in the

United States.’’7

Halverson’s Above Universal City shares with Raeburn

a sense of optimism in the power of technology to improve

lives, while forging a unique alliance between the built and

natural environments. As the image itself suggests, Los

Angeles may be far from pristine, but its industrial sprawl

isn’t approaching post-apocalyptic status. Most of the city

exists in a visual continuum between a historical ideal and

more recent images that allude to its impending, catastrophic

doom. Frighteningly vast and beautifully complex, these are

the spaces of the twenty-first-century sublime. B

34 B O O M C A L I F O R N I A . C O M

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020

Notes

1 Leo Marx, ‘‘The Idea of Nature in America,’’ Daedulus 137:2

(Spring 2008): 9.2 The ‘‘transcendental sublime’’ was coined by Earl Powell in

his essay ‘‘Luminism and the American Sublime,’’ in John

Wilmerding, ed., American Light: The Luminist Movement,

1850–1875 (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art,

1980), 69–94. See also Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture:

American Landscape Painting, 1825–1875 (Oxford and New

York: Oxford University Press, 1980, 1995, 2007).3 See Rob Wilson, ‘‘Techno-Euphoria and the Discourse of the

Sublime,’’ boundary 2 19:1 (Spring 1992): 208.4 Ibid., 207.

5 For more on the idea of horror and the banal as related to Los

Angeles, see Cecile Whiting, ‘‘The Sublime and the Banal in

Postwar Photography of the American West,’’ American Art, 27:

2 (Summer 2013): 51.

6 The antithetical relationship between Ruscha and the sublime

is explored fully in Cecile Whiting, ‘‘The Sublime and the Banal

in Postwar Photography of the American West,’’ American Art,

27:2 (Summer 2013): 44–67.

7 City Engineer, Annual Report, 1923–24, 23. Cited in Matthew

W. Roth, ‘‘Mulholland Highway and the Engineering Culture of

Los Angeles in the 1920s,’’ Technology and Culture, 40:3 (July

1999): 547–8. The eastern portion of Mulholland Highway was

renamed Mulholland Drive in 1939.

Mulholland Above Universal City, Los Angeles, California, Karen Halverson. COURTESY OF THE AUTRY NATIONAL CENTER, LOS ANGELES.

BOOM | F A L L 2 0 1 4 35

Dow

nloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/boom

/article-pdf/4/3/28/381802/boom_2014_4_3_28.pdf by guest on 23 M

ay 2020