OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

Transcript of OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

1/8

OECD Urban Policy Reviews: Mexico 2015. Transforming Urban Policy and Housing Finance.

DOI:10.1787/9789264227293-en

66- 1. CITCES, HOUS NG AND PENSIONS IN MEXICO:

AN

OPPORTUN

ITY TO BOLSTER

GROWfH

AND WELL-BEING

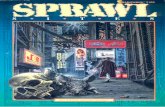

Suboptimal, costly urban developmentpatterns

Urban sprawl

Cities

in

many O

ECD

countries are sprawling - t

hat

is, the growth

in

the built-up area

has outpaced the population growth, occurring at ever greater distances from the centre

city and in increasingly dispersed (rather t

han

clustered) patterns. Figure 1.24 classifies

urban development trends across OECD countries between 200] and 2011 into

four categories: i} increasingly single-hub (monocentric) urban areas with suburban

dispersion;

ü

increasingly multi-hub (polycentric) urban areas;

iü

increasingly compact

urb

an

areas; and iv increasi

ng

ly sprawled

ur

ban areas. The latter two development

patterns are the

most

dominant. 1n severa European countries, including Austria,

Belgium, Denmark, Germany, the

Ne

therlands, Norway, Sweden and the

United Kingdom, the trend since 200 1

has

b

ee

n towards more compact cities: the distance

to the city centre thus decreased as the concentration

of

population incr,eased, indicating a

den

ser

built structure. Increasi

ng

ly sprawled cities represent the second most common

development

pa

ttern across the OECD; Mexico belongs to this category. In the case

of

Mex

i

co

, urban development occurred

at

increasing distances from t

he

cent

re city (x-axis)

and, albeit to a lesser extent, was increasingly deconcentrated (y-axis) - or in other words,

urban development was increasingly dispersed, rather than clustered, within urban areas.

Figure 1.

24

. Ur

ba

n development patterns ac ross OECD countries, 2001-11

lncreasingly single·hub (monocentric)

urban areas

with

suburban dispersi

on

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

Korea

~ al Á

u

xembourg

Austria

Germany .feelgiu

Sweden

•

Norway

•

N e t h e r t a n

ca

rÍda

Japan,

Estonia

•

·0.01

.Q02

Poland

•

lnCleasingty sprawled

urbanareas

Czech Republi

c_

_

r e l n d

p i n

France

•

ex

o

a n d SWi rla

rd

~ i ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

• Slovenia

Chile

•

Greece

•

l ncreasingly compact urban areas

-0.03

lncreasíngly multi·hub

(potyc

en1ric

) urban areas

-0.04 -0.03 -0.02 .0.01 o 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04

O.OS 0.06

Change in population decentralisation. 2001·11 (aver

age

distance rom he

ma

in centre weighted

by

population,

AOC

iodex)

0.07

Notes:

The

vertical axis measures the average change in the degree of spatial de-concentration of population

withiu functional urban areas. Spatial de-concentration is measured through an enn·opy index where lúgher

valnes s

ugg

est a Jow degree

of

clustering (higher dispersiou) of people in space. On

th

e horiz

on

tal axis, the

ADC index measures the extent to which population is located far from the main urban centre. Higher values

indicate

Jb.igher

distances, 011 average, from the centre (lúgher decentralisation). Cou

ntry

values are obtailled as

averages of values for functional urban areas. See source for details.

Sourc

e Veneri, P. (forthcoming), "Urban spatial stmcnire in OECD cities. Is urban population decentralising

or clusteriug?

",

OECD Regional Developm ent Working Papers, OECD Publishiug, Paris, fo1thcoming.

OECD URDAN

PO

LICY

RE

V EWS: 1' EX CO . TRANSFO&\,flNG URDAN POL CY ANO HOUS NG F NANCE O O

ECD

2015

ttp: www. eepee .com D g ta -Asset-Management oec ur an-rura -an -reg ona - eve opment oec -ur an-po cymexico-2015_9789264227293-en#page1

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

2/8

l. CITIES, HOUSING AND PENS ONS IN MEXJCO: AN OPPORTIJNITY TO BOLSTERGROWTH AND WELlrBEING -

67

While urban sprawl is

ev

ide

nt

on a national scale for Mexico. different patterns

emerge across the country's 30 largest metropolitan zones. In almost half of the metro

zones, population growth outpaced

the

growth

of

the urban area - th

at

is, overall density

actually increased in these areas (Figure 1.25) Metropolitan zones that experienced

re latively large urban expansion before 2000 (e.g. Valle de México) have experienced a

period of densification since.

Figure 1.25. Urban

spraw

l in the largest Mexican metropolitan zones, 2000-10

Urban sprawl index across metropolitan zones with at least 500 000 inhabitants

60 40

-

20 o 20 40 60 80 100

1

20

1

40

u rez

Quereta o

o

león

E

Guadalajara

o

La Laguna

o

Valle de Mexlco

o

Monterrey

o

Tijuana

o

o

San

Luis Potosi

Puebl

a T

axcala

To

luca

cancun

Chihuahua

Acapulco

Ve

raCfl.Jz

Pachuca

'

Mex

ica

li

Celaya

Morelia

Merida

o

Aguascalientes

o

Oaxaca

o

Tampico

o

o

C

uer

nav

aca

'

Reynosa-R

io

Bravo

Villahermosa

Xalapa

Poza Rica

Sa

lt

llo

Tuxtla Gutierrez

Note

A p

os

itive sprawl index indicates the occurrence of urban sprawl; a negative va lue indicat

es

higher

population growth than urban expansion and thus densification; and a value of zero indicates that population

and the urban area grew

at

the same rate.

Source

Based on data from INEGI, Population Census 2000 and

20

1

.

Yet the urban sprawl index only tells one side of the story. While the density of the

overall metropolitan zone may have increased, the location and intensity of densification

(or de-densification) within the metro zone varies. Figure 1.26 dispfays the change in

urban population density within metropolitan zones between 2000 and 2010 based on

distance to the city centre. ln most cases, the central area located within 2.5 kilometres

from the city centre experienced a fall in population density during this period; this drop,

likely due to population loss and shrinking household size as one moves further from the

city centre (INEGI, 2012b), was countered by

an

often much larger increase in population

density in areas located more than 1O ki lometres from the city centre. Areas located

farther away from the centre are more likely to be home to new housing developments.

Thus, higher population densities

on

the outskirts and lower population densities in the

cen

tr

e can also be explained by people moving from the centre into the outskirts.

Figure 1.27 shows this development for the case of Puebla-Tlaxcala. While the overall

urban sprawl index indicates a densification of this metropolitan zone, the population

changes by distance to the centre revea that this densification occurred in areas located

more than 5 kilometres away from the centre, whereas population densities fe ll within

2.5 kilometres of the centre.

OECD URBAN POLICY REVIE\VS:

MEXICO

• TRANSFORMING URBAN POLI

CY

AND HOUSING FINANCE C

OECD 20

15

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

3/8

68

l . C TIES, HOUSfNG AND PENS ONS IN MEXICO: N OPPORTUNITY TO BOLSTER GROWTH ANO WELL-BEING

Figure 1.26. Cbange in population density witb respect to distance to tbe city cen

Less than 2 .5 km

-3

0

5

0

15

30

o

E

o

o

8

§

§

i

i

e¡

8

o

Valle de Mexico

Guadalajara

Monte

rr

ey

Puebla-Tlaxcala

Toluca

Tijuana

León

Juarez

La Laguna

Que retaro

San

Lu

is Potosi

Merida

Mex icali

Aguascalientes

Cuernavaca

Acap

u

lco

Tampico

Chihuahua

Morelia

Sa llillo

Verac

ruz

Villahermosa

8 Reynosa-Rio Bravo

'

Tuxtla Gutierrez

Cancun

Xalapa

Oaxaca

Ce aya

Poza Rica

Pachuca

Ave

rage

00

-

Va lle de Mexico

Guadal

aja

ra

Monterrey

Puebla-Tlaxcala

Toluca

Tijuana

Leó

n

Juarez

La

Laguna

Que eta o

San Lu is Potosi

Merida

Mexicali

Aguascalientes

Cuernavaca

Ac

ap

ulc

o

Tampi

co

Chihuahua

More lia

Salt

illo

Veracruz

Villahermosa

Reynosa-Rio Bravo

Tuxtla Gut ierrez

Cancun

Xalapa

Oaxaca

Ce laya

Poza Rica

Pachuca

Ave

r

age

2.5

-

5km

0

Source

Based on data from INEGI, Popu lation Census 2000 and 2010.

100

-100

Va

lle

de Mex

ico

Guadal

ajara

Monter

rey

Puebla-Tlaxcala

Toluca

Tijuana

León

Juarez

La Laguna

Que eta o

San Luis Potosi

Me rida

Mexicali

Aguascalientes

Cuernavaca

Acapu

l

co

Tampico

Chihuahua

Morelia

Saltillo

Veracruz

Villahe rmosa

Reyn

osa

-Rio Bravo

Tuxtla Gutier

rez

Cancun

Xa

l

apa

Oaxaca

Celaya

Poza R ica

Pachuca

Average

5-

10 km

0

100

200

R

OECD URBAN POL CYREVIE\VS: MEXICO- TRANSFORNON

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

4/8

l CITIES, HOUS NG

AND

PENSIONS IN

MEX

JCO:

AN

OPPORTIJNITY TO B

OLS

TER

GROWTH AND

WELLrBEING - 69

Figure 1.

27. Population density in Puebla-Tlaxcala, 2000 and 2010

Population

per

square km

c Less than 1 000 - 1 000-2 500 - 2 500 - 5 000 - 5

000-

100 00 - Morethan 100 00

u rce

Based on INEGI Population Census 2000 and 2010.

There are, however, a few exceptions, in which metropolitan zones experienced a

densification regardless of the distance to the centre. Such is the case for Xalapa,

Poza Rica, Toluca and Tuxtla Gutierrez. In Xalapa and Tuxtla-Gutierrez (Figure 1.28),

for instance, the urban footprint remained fairly unchanged since

2

and thus the

process of densification appears to have been caused by an increase in population in that

area. comparatively low share of unemployment and a moderate share of informal

employment may have further attract·ed individuals to this metropolitan zone. Xalapa and

Tuxtla Gutierrez also have a relatively high share

of

university graduates

31

%

and

26%

respectively). Other areas that are facing a less attractive environment (such as Juárez,

which has higher unemployment rates and also higher rates

of

insecurity; Figure 1.41),

experienced a loss in population density, regardless

of

the distance to

the

centre.

In

Juárez, for instance, the overall loss in population density is captured

by

a positive urban

sprawl index.

Urban sprawl in

Mexico

was fostered by multiple causes, including the expansion

of

both informal and formal settlements, as well as the location and type

of

housing

development. One

cou

ld posit that, as access to subsidised housing loans is conditional

on

formal employment, sprawling metro zones with a large share

of

informal employment

are more likely to sprawl due to informal settlements; by contrast, in areas with a low

share of informal employment, urban sprawl is more likely to be related to the

development

of

fonnal settlements for low-income groups (such as those financed by

OECD Ull.BAN POLICT REVIEWS: MEXICO - TRANSFORM NG URBAN POLICY AND HOUS NG FINAN

CE

O OECD 2015

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

5/8

70 -

l

CITIES, HOU

SI

NG AND PENS ONS IN MEXICO: AN OPPORTUN ITY TO BOLSTER GROWfH AND W ELL-BEING

INFONAVIT). Distinguishing between the different roots of sprawl is critica

to

determine the most appropriate policy responses, which will be discussed further in

Chapters 2 and 3.

Figure

1 28

. Population density in Tuxtla Gutierrez,

2000 and 2010

2000 2010

2

Population

per

square km

D

Less than 500 500 2 500 2 500 5 5 10 More than 1

Source:

Based on INEGI Po

pulat

ion Census

2000

and 20 1

O.

Both

the location and type

of

housing

ha

ve contributed to urban sprawl.

In

tenns of

formal housing development, many homes have been built on the periphery

of

Mexican

citie

s

which combines both the ease and the profitability for developers to meet the

housing needs of low-income households_ According to data in the National Housing

Registry Registro Único de Vivienda, RUV),

5

most housing constructed after

2005

is

located on the periphery or on the outskirts of metro zones (Figure

1.29).

Only a small

share of housing constructed since

2005

is located in the centre of the metropolitan zones.

Although not ali housing constructed after

2005

is captured in this registry, the findings

still provide interesting insights as to the trend of the location

of

housing.

A

hou

sing sup

pl

y dominated

y

individual houses and homeowners

Urban sprawl and the de-densification

of

urban areas are also fostered by the

predominant type

of

housing in Mexico: the prevalence

of

individual homes. According

to the

2010

Census, about

90% of

Mexico's housing stock is comprised

of

individual

homes casa independiente) (INEGI,

2013).

Although the share differs slightly according

to the size of the urban area, even in the largest urban area with over

100 000

inhabitants,

individual houses make up the vast majority

of

homes (84%). This share is substantially

20k

OECD URBAN POLICYREVIEWS : MEXICO • TRANSFORMING URBAN POLICY AND HOUS NG F NANCE O OECD 20 15

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

6/8

l. CITIES, HOUS NG AND PENSIONS IN MEXJCO: AN OPPORTIJNITY TO BOLSTER GROWTH AND WELLrBEING -

7

higher than is found in many

ot

h

er

OECD countries; for instance, detached/individua l

homes make up roughly 64%

of

the total housing stock

in

the United States (American

Housing Survey, 2013), 62% in Canada (Statistics Canada, 20

11

), 62% in Germany

(Statistisches Bundesamt, 2013) or 79%

in

Argentina (íNDEC, 2010). However, the share

of detached homes in Mexico differs slightly by the size of locality: in highly urbanised

areas with more than 100 000 inhabitants, the share

of detached homes is 84%, slightly

lower than the national average but still significantly higher than the share in many other

countries.

Figure 1.29. Where have most form l homes been built since 2005?

Location

ofhousing

completed

or

remodelled; aggregated years 2006- l3 by size of metro zone

• Peripheiy

• Outskirts J

ntermedate

e Centre " Sh..-e housing <

60

000 USO

100%1TT1"'ft:r

c::n:ln=n::n::nm::1l=11"rc::n:'1l"'fRCroo-i::n=n:::n:oRt:rci:::rMln...ro?"tt:n"'ft:rRT""n::l" ''l"Cl1m=l-.::ri:fTTl.....,."'""rTTT"tt:lln"C1"'1T"TrT>on::rR

90%

80%

700,{,

90

500/o

400/o

300,{,

200/o

100/o

0%

¡

5 i l 2

[Jl2

E ~ · ~ ~ 8 ~

_ - u ~

~ ~ ~ · ~

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ l - r ~ ~ ~ X c n ~

~ ~ F ~ c ~ ~ ~ - ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ g ~ ~ ~ w r o r o ~ ~ ~

~ o ~ ~

~ ~ ~ O ü ~

3 m _ ~ o .

n : ~ .

º '

e :O ' U

g

~ ~

Q'.

1 000

000

or

more

500 o 0·999

999

Source

SHF Housing Statistics (Data series: Total number of prope11ies valued by year of completion of the

work or remodelling), accessed April 2014

Home ownership is by far the dominant form

of

tenure in Mexico, with 76.4%

of

housing owner-occupied (INEGI, 20 10). As elsewhere in Latin America, Mexico's renta

housing market generally remains shallow and underdeveloped relative to many OECD

countries (see OECD 2013g; 2012c). According to Mexico's National Institute of

Statistics and Geography

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografia e Informática,

INEGI), approximately 16% of Mexicans were formal renters in 2012.

In

2009, the most

recent year for which comparative t,enure data are available, Mexico's share of formal

renta housing (14%) was

just

behind Poland (15.4%) and Chile (17%), surpassing only

six OECD countries (lceland, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, Greece and Spain)

(Figure 1.30). Nevertheless,

Mexico's

share ofrenta housing is underestimated

in

official

statistics, as a large share

of

the renta stock is in the informal sector. Accordingly, the

national share of rental housing was likely eloser to 23% in 2012, by adding to the share

of formal renters a portion of the 14% who reported living

in

"borrowed" housing

(INFONA VIT, 2013). lt is also important to point out that nearly ali informal settlements

- which house roughly a quarter

of

Mexican households - are considered owner-occupied

(whetheT or not they have received official titles to their homes or land through the

government's titling programmes). And, moreover, informal renting occurs widely

throughout informal settlements and is widely underreported.

OECD Ull.BAN POLICT REVIEWS: MEXICO • TRANSFORM NG URBAN

PO

LICY AND HOUS NG FINAN

CE

O OECD 2015

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

7/8

72 - l ClTlES, BOUSING

AND

PENSIONS IN MEXICO: AN OPPORTUNITY TO BOLSTERGROWTH

AND

WELL-BEING

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 1.30. Tenure structure across OECD countries

Percentage of dwelling stock, 2009

• Rental

müwner

o Co-operati

v

• Other

Z Z ü X X W Z Z O W W Z

> >

W 0 I C 0 N

m

W N Z W I

I G W ü z - ü G m ü Z O Z O ü '

Note: The statistical data for Israel are supplied by

and

tu1der the responsibility

of

the relevant Israelí

authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights,

East Jemsalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms

of

ntemational law.

Source: OECD Housing Market questionnaire, in: OECD (2012c), OECD Economic Surveys: Chile 2012

OECD Publishing, París, http://dx.doi.org/I 0.1787/eco surveys-chl-2012-en.

Despite its large share of the current housing stock, home ownership has not always

been the housing tenure preference of Mexicans: home ownership rates in Mexico City,

for instance, grew by 45% between 1950 and 1990. Mexico's general policy orientation

towa

rds home ownership is relatively consistent with trends throughout Latin America:

the average renta tenure in Mexico was just above the Latin American and roughly

comparable to the share of renter-occupied dwellings in Brazil, Chile, El Salvador,

Guatemala and Uruguay in 2007 (Bouillon, 2012; Rojas and Medellín, 2011). Consistent

with broader trends in Latín America, the share of renta housing in the overall urban

housing stock dropped dramatically between the 1950s and 2000s (Figure 1.31 ).

In

Mexico City and Guadalajara, for instance, owner-occupied dwellings accounted fo r less

than 30% of ali housing in 1950, increasing to 43% in 1970 and to around 70% by 1990;

after peaking in the 2000s (at 74% and 68%, respectively), homeownership rates fell

slightly by 2010 (Blanco et al., 2014).

Moreover, renta housing in Mexico tends to be geographically concentrated in urban

areas in

th

e centre of

th

e country. Nearly half (approximately 46%) of the renta] housing

stock is located in just five states: the Federal District, the state of Mexico, Jalisco,

Veracruz and Puebla (Peppercorn and Taffin, 2013). The size ofthe metropolitan zone is

not necessarily indicative of a large renta market: while sorne of Mexico's largest

metropolitan zones record a high

ra

te of rented

dw

ellings, surpassing 30% in the

Va

lle de

México, Guadalajara and Tijuana, others ha

ve

markedly lower rates (I 8% in Monterrey

and 18% in La Laguna) (INEGI, 201 O). In contrast, renter-occupied housing makes up

around half of the total housing stock in some large OECD metropolitan areas. The

national share of renter-occupied housing in the United States in 2011 was 35.4%, with

renta] rates in the most populous US metropolitan areas Ied by Los Angeles (50.8%) and

New

York (48.9%) (US Census Bureau, 2013). In France, renter-occupied housing

represented just

und

er half (49.3%)

in

the

Pari

s-Ile-de-France r

eg

ion in 201O e

dging

out

owner-occupied housing (47.6%) (lNSEE, 2014).

OECD URBAN POLICY REVIEWS: 1" EXICO - TRANSFORMING URBAN POLlCY AND HOUSINGF NANCE O OECD 201 S

-

8/17/2019 OECD Sprawl 2015 (1)

8/8

l. CITIES, H

OU

S NG

AND

PENSIONS IN MEXJCO:

AN

O

PPOR

TIJNITY TO BOLSTER GROWTH

AND

WELLrBEING - 7

Figure 1.31. Evo

lu

tion

ofhome

own

ers

hip in selected

Lat

in Ameri

can

cities, 1950s-2010s

Mex

.coCity - - - Guadalajara - · - Bogota

- - - - · Me

dl

ellin

- Cali

- • - Santiago

de

Chile

•

•••• •••

•

Rio

de Janeiro

- -

Sao Paulo

Buenos Aires

90%

80%

0

.

60%

-

50%

___

................

- .

. . .

40%

·

-

': ':..:. -... .

.·.-

30%

20%

10%

0%

1950 1970 1

990

2000 2010

Notes:

Data for Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires correspond to centre city, not the metropolitan

area.

Source: Adapted from Blanco, A.O. et al. (2014), Renta/ Housing Wanted Policy Options f or Latín America

and the aribbean

In

er-American Development Bank, available at:

www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/20 l4/ l 3900en.pdf. Data from Gilbert (2012); 20

Os

data for Colombia

(Bogota, Medellín, Cali) from MECOVI 2010 and for Chile (Santiago de Chile) from MECOVI 20

11

; 2010s

data for Rio de Janeiro from IPUMS, 2013.

Spatial segregation poor access to services

Low-income groups are more likely to be located on the outskirts and the periphery of

a city, a trend that is fostered by housing subsidies and lower land prices outside the

cities. Figure 1 32 displays the clustering of the average years of schooling within census

(AGEB) tracts.

6

Black coloured fields indicate that the average years of schooling is

significantly higher, b lue fields indicate that average years

of

schooling are significantly

lower than the average within the respective metropolitan zone. As more education is

closely linked with higher income, these maps indicate whether spatial segregation might

be a problem. In the metro zones mapped below, spatial clustering by educational level

occurs to varyi

ng

extent

s

Two different spatial patterns are visible: in severa

metropolitan zones, groups with lower educational attainment are clustered on the

outskirts, away from t

he

centre (e.g. Cancun, Juarez, Monterrey); in other metropolitan

zones, there is a clear divide ( e.

g

north/south, east/west) through the metropolitan zone

(e.g. Guadalajara and Merida). Moreover, in sorne metropolitan zones, spatial segregation

can appear in the form of disadvantaged areas with poorer access to basic services, such

as electricity, water and drainage.

Beyond access to basic services, the quality

of

services in a given area also ma

tt

ers In

Guadalajara and

Mo

nterrey, the average test s

eor

es per school that took part in ENLACE

7

in 2013 revea spatial clustering of school/student performance. For one, areas that are

characterised by lo·w average educational attainment also exhibit poorer performance

of

schools. Second, schools on the outskirts tend to perform worse than the ones in the

centre (Figure 1.33).

OECD URBAN POLICT REVIEWS:

ME

XICO - TRANSFORM NG URBAN POLICY AND HOUS NG FINAN

CE

O OECD 2015