Founder Institute Sydney - April 9, 2013 - Naming & Branding : Step Change Marketing

Obamacare branding naming needs work

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

arman-beirami -

Category

News & Politics

-

view

205 -

download

1

Transcript of Obamacare branding naming needs work

By William M. Sage

ANALYSIS & COMMENTARY

Why The Affordable Care ActNeeds A Better Name: ‘Americare’

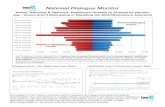

ABSTRACT The culmination of a century’s effort to enact universalcoverage in the United States is a law with an uninspiring title, thePatient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and an even more awkwardacronym, PPACA. The Obama administration has decided to call thelegislation the Affordable Care Act, but the expansion of health coveragethat the law sets in motion has no name, and therefore no identity. Itbadly needs one.

To be sustainable as a system, healthcare must be accessible, available,and affordable. The U.S. healthreform law passed in 2010, awk-wardly named the Patient Protec-

tion and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), charts atechnical path toward theseobjectives.However,its name offers insufficient inspiration to stay oncourse. The law comes up short on what legalscholars call “expressive value,” meaning sym-bolism. A name such as Americare would tie thenew law’s many complex strands together,encouraging a sense of solidarity among ordi-nary Americans that will be necessary to achievethe legislation’s goals.The name Americare, or something like it,

would reinforce public understanding that thelaw entitles all Americans to health insurance,ensures access to care, and protects against fi-nancial catastrophe. These are long-standingand important ideals. In 1993 and 1994,PresidentBill Clintonattempted tobuild supportfor his reform proposal by distributing thou-sands of “health security cards” bearing thepresidential seal. Today, “Americare cards” couldserve an equally important, and noble, symbolicpurpose.Over time, a program called Americare, like

Medicare, would become something that bene-ficiaries would not only accept, but would alsodefend. Behavioral economics recognizes an en-dowment effect: People demand more to part

with something they own than they are willingto pay for an identical item they lack. This is whycongressional Republicans attacked the reformlegislation as undercuttingMedicare, a programmany of them had long sought to privatize andeventually eliminate. They departed from thatposition because Medicare is, whereas an un-named new programmerelymight be, andwouldbe undervalued by the public as a result.Were the Affordable Care Act’s programs to be

rebranded, all eligible participants would signup for anAmericare planwith the specific sourceof coverage appended.1 One person might havean Americare—Blue Cross plan, while someoneelse would have Americare—Medicare. A com-mon identity would convey the point that uni-versal participation makes it possible to haveuniversal insurance that does not discriminateagainst the sick. It would also remind insurersthat they are no longer permitted to compete byavoiding risk and are now expected to competeby improving care.The name Americare would assert a collective

interest in health system value and efficiency. Itwould build courage to do more than tinker atthemargins with new paymentmethods, organi-zational structures, andprofessional skills.Mostimportant, a shared identity would signal ourdecision to rein in special interests and begina social conversation about redesigning healthcare delivery to produce the most cost-effectiveresults.2,3

doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0465HEALTH AFFAIRS 29,NO. 8 (2010): 1496–1497©2010 Project HOPE—The People-to-People HealthFoundation, Inc.

William M. Sage ([email protected]) is vice provostfor health affairs at theUniversity of Texas at Austin,where he holds the James R.Dougherty Chair for FacultyExcellence in law.

1496 Health Affairs August 2010 29 :8

After Health Reform

Health improvement is critical to the sustain-ability of our health care system. Framing thenew law’s initiatives to increase populationhealth as part of Americare would underscorethe message that individuals and communitiesshare responsibility for unhealthy behaviorssuch as smoking, overeating, and avoidingphysical activity. Putting poor health in the samecollective context as health insurance might fi-nally persuade us to connect health care provid-ers to schools, schools to workplaces, andworkplaces to other community sites that canpreserve and promote health.Three concerns probably dissuaded the reform

law’s proponents from clearly proclaiming itsidentity. First, a named program might havefrightened America’s “haves” by suggesting thatfamiliar insurance arrangements would change.Second,bestowinga singlenameon theprogrammight have seemed socialistic; even the pro-posed “public option”wasabandoned in the finallaw because it connoted a much-feared govern-ment takeover. Third, the Congressional BudgetOffice might have interpreted a unitary descrip-

tor as evidence that funds flowing from individ-uals and employers to insurers were no longer amatter of private purchase but constituted a tril-lion-dollar tax increase, coupled with a trillion-dollar boost in federal spending.This political price was too steep to pay during

the legislative debate prior to enactment of thelaw. In contrast, naming the program now islikely to reduce its political vulnerability. Oppo-nents of reform mainly accuse the new law ofcryptic complexity. A name such as Americareoffers a straightforward message in response.A national identity would also help counter ac-

cusations of unaffordability. Health care spend-ing has never been well understood by averageAmericans.4,5 During the legislative debate, me-dia commentators approached the proposed lawas a compilation of personal costs and benefits.They readily explained “how reform affects you”but seldom considered “how reform affects us”as a nation.Americans generally favor low taxes and small

government and are skeptical about the connec-tion between health reform and deficit reduc-tion. Shared participation in a named programis necessary to link our physical health as indi-viduals to the fiscal health of our country. Prof-ligate health spending diverts large amounts ofpublic money from other critical needs, such aseducation. It represents a drain on employmentcompensation that crowds out cashwages, and itposes a long-term threat to the fiscal stability ofthe United States.At severalpoints inhistory,weAmericanshave

shown ourselves capable of pulling together onhealth care to providemutual assistance, expresspatriotism, and invest in our future.6Naming thenew systemAmericare would expressly associateboth health security and stewardship of scarceresources with citizenship in one of the greatestnations on earth. ▪

NOTES

1 Rep. Fortney (Pete) Stark proposeda Medicare-for-all system in theAmeriCare Health Care Act in 2007.Names resembling “Americare” havealso been used by private health carecompanies.

2 Vladeck BC. The political economy ofMedicare. Health Aff (Millwood).1999;18(1):22–36.

3 Jacobs LR. Politics of America’ssupply state: health reform andtechnology. Health Aff (Millwood).

1995;14(2):143–57.4 Blendon RJ, Hunt K, Benson JM,

Fleischfresser C, Buhr T. Under-standing the American public’shealth priorities: a 2006 perspective.Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(6):w508–15.

5 Blendon RJ, Hyams TS, Benson JM.Bridging the gap between expert andpublic views on health care reform.JAMA. 1993;269(19):2573–8.

6 Sage WM. Solidarity: unfashionable

but still American [Internet]. In:Murray TH, Crowley M, editors.Connecting American values withAmerican health care reform.Garrison (NY): Hastings Center;2009 [cited 2010 Jun 18].p. 10–12. Available from: http://www.thehastingscenter.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/Primers/solidarity_sage.pdf

Shared participationin a named program isnecessary to link ourphysical health asindividuals to thefiscal health of ourcountry.

August 2010 29 :8 Health Affairs 1497