NTRODUCTION TO IELDWORK - SAGE Publications · ing annihilation. However, ... method that appears...

Transcript of NTRODUCTION TO IELDWORK - SAGE Publications · ing annihilation. However, ... method that appears...

Fieldwork must certainly rank with themore disagreeable activities that human-ity has fashioned for itself. It is usually

inconvenient, to say the least, sometimes physi-cally uncomfortable, frequently embarrassing,and, to a degree, always tense. Although anthro-pology and sociology still appear to have thelargest proportion of field researchers amongthe social sciences, their number is growing sig-nificantly in such diverse disciplines as nursing,education, management, medicine, and socialwork. Field researchers have in common thetendency to immerse themselves for the sake ofscience in situations that all but a tiny minorityof humankind goes to great lengths to avoid.Consider some examples: Raymond A. Friedman(1989) said that the first contact with his researchsubjects in a study of labor negotiations was adisaster. The plant manager was opposed to hispresence. He entered the field in the middle of arancorous intraunion fight over seniority. Andhe initially chose an inopportune place (a bar) tointerview workers. Carol S. Wharton (1987)managed over a ten-month period the delicateobserver-as-participant role of researcher andcounselor-advocate in a shelter for battered

women. Peggy Golde (1986, pp. 67-96) struggledto learn about aesthetic values and practices in aMexican village against the odds of physicalisolation, a contaminated water supply, and anew language.

For most researchers the day-to-day demandsof fieldwork are fraught regularly with feelingsof uncertainty and anxiety. The process of lead-ing a way of life over an extended period thatis often both novel and strange exposes theresearcher to situations and experiences thatusually are accompanied by an intense concernwith whether the research is conducted and man-aged properly. Researcher fieldwork accountstypically deal with such matters as how the hur-dles blocking entry were overcome successfullyand how the emergent relationships with sub-jects were cultivated and maintained during thecourse of the study; the emotional pains of thiswork rarely are mentioned. In discussing anthro-pologists’ fieldwork accounts, Freilich (1970)writes:

Rarely mentioned are anthropologists’ anxiousattempts to act appropriately when they knewlittle of the native culture, the emotional pressures

Reprinted from Experiencing Fieldwork, Copyright © 1991 Sage Publications, Inc.

2

INTRODUCTION TO FIELDWORK

WILLIAM B. SHAFFIR

ROBERT A. STEBBINS

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 2

to act in terms of the culture of orientation, whenreason and training dictated that they act in termsof the native culture, the depressing time when theproject seemed destined to fail, the lonelinesswhen communication with the natives was at alow point, and the craving for familiar sights,sounds, and faces. (p. 27)

Despite the paucity of accounts describing theless happy moments of fieldwork, such momentsare likely to be present in most, if not all, fieldstudies. This is suggested in the discussions ofmembership roles in field research (Adler &Adler, 1987) and field relations (Hammersley &Atkinson, 1983), and by the frequency withwhich they become topics of conversationamong researchers. Perhaps most unhappymoments in the field are not as painful as that ofGini Graham Scott (1983) whose position ascovert observer of a black magic group (Churchof Hu) was discovered by other members:

At first, as I walked in, I was delighted to finallyhave the chance to talk to some higher-ups, but inmoments the elaborate plotting that had takenplace behind my back became painfully obvious.

As I sat down on the bed beside Huf, Larelooked at me icily. “What are your motives?” shehissed.

At once I became aware of the current ofhostility in the room, and this sudden realization,so unexpected, left me almost speechless.

“To grow,” I answered lamely. “Are youconcerned about the tapes [containing researchdata]?”

“Well, what about them?” she snapped.“It’s so I can remember things,” I said.“And the questions? Why have you been ask-

ing everyone about their backgrounds? What doesthat have to do with growth?”

I tried to explain. “But I always ask peopleabout themselves when I meet them. What’swrong with that?”

However, Lare disregarded my explanation.“We don’t believe you,” she said.

Then Firth butted in. “We have several peoplein intelligence in the group . . . we’ve read yourdiary . . . ”

At this point the elaborate plotting going onbehind my back became clear, and I couldn’t thinkof anything to say. It was apparent now they con-sidered me some kind of undercover enemy orsensationalist journalist out to harm or expose theChurch, and they had gathered their evidence to

prove this. Now they were trying the case, thoughit was obvious the decision had already beenmade. Later, Armat explained that they had fearsabout me or anyone else drawing attention to thembecause of the negative climate towards cultsamong “humans.” So they were afraid that anyoutside attention might lead to the destruction ofthe Church before they could prepare for the com-ing annihilation. However, in the tense setting ofa quickly convened trial, there was no way toexplain my intentions or try to reconcile themwith my expressed belief in learning magic. OnceFirth said he read my diary, I realized there wasnothing more to say.

“So now, get out,” Lare snapped. “Take offyour pentagram and get out.”

As I removed it from my chain, I explainedthat I had driven up with several other people andhad no way back.

“That’s your problem,” she said. “Just be goneby the time we get back.” Then threateningly sheadded: “You should be glad that we aren’t goingto do anything else.”

“There are buses,” Huf remarked. (pp. 132-133)

Nonetheless, after hearing field researchersdiscuss their work, one has to conclude thatthere are exceptional payoffs that justify theaccompanying hardships. And for these scien-tists, the payoffs go beyond the lengthy researchreports that present sets of inductive generaliza-tions based on direct contact with other waysof life. Fieldwork, its rigors notwithstanding,offers many rewarding personal experiences.Among them are the often warm relations to behad with subjects and the challenges of under-standing a new culture and overcoming anxi-eties. In short, entering the research setting,learning the ropes once in, maintaining workingrelations with subjects, and making a smoothexit are difficult to achieve and sources of pridewhen done well.

From another perspective, the desire to dofieldwork is founded on motives that drivefew other kinds of scientific investigation. To besure, field researchers share with other scientiststhe goal of collecting valid, impartial data aboutsome natural phenomenon. In addition, how-ever, they gain satisfaction—perhaps betterstated as a sense of accomplishment—fromsuccessfully managing the social side of theirprojects, which is more problematic than inany other form of inquiry. Though they raise

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 3

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 3

questions of validity (Johnson, 1975, p. 161),gratifying relations between observers and sub-jects frequently emerge in the field. At the sametime, being accepted by subjects as a group iscrucial for conduct of the study (Cicourel, 1964,p. 42). Observers must be able to convince theirsubjects (and sometimes their professionalcolleagues) that they can satisfactorily do theresearch and that their interests are of enoughimportance to offset the frequent inconvenience,embarrassment, annoyance, and exposure thatnecessarily accompany unbiased scientificscrutiny of any group. It is in attempting tosolve this basic problem, which recurs through-out every study, that many of the unforgettableexperiences of fieldwork occur.

Completion of a fieldwork project is also anaccomplishment because the “situation of socialscientists” (Lofland, 1976, pp. 13-18) discour-ages it so. Lofland notes that many social scien-tists are unsuited temperamentally for thestressful activity of such an undertaking becausethey are rather asocial, reclusive, and sometimeseven abrasive. Furthermore, all university-basedresearch must be molded to the demands of theuniversity as a large-scale organization. Gettingacquainted with an essentially foreign way oflife is complicated further when the research ispursued intermittently after classes, before com-mittee meetings, between deadlines, and the like(e.g., Shaffir, Marshall, & Haas, 1980). To thisis added the lack of procedural clarity that char-acterizes field research; there are few usefulrules (unlike other forms of social research)available for transforming chaotic sets of obser-vations into systematic generalizations about away of life. Then there is the preference of fund-ing agencies for quantitative investigations,which pushes the field-worker yet another stepin the direction of marginality. Finally, the verystyle of reporting social scientific findings,abstruse and arcane as it tends to be, contrastsbadly with the down-to-earth routines of thepeople under study. When they find it next toimpossible to see themselves in the reports ofthe projects in which they have participated,they are rendered ineffective as critics of theaccuracy of the research.

Fieldwork is carried out by immersing one-self in a collective way of life for the purpose ofgaining firsthand knowledge about a major facet

of it. As Blumer (1986) puts it, field research onanother way of life consists of:

getting closer to the people involved in it, seeingit in a variety of situations they meet, noting theirproblems and observing how they handle them,being party to their conversations and watchingtheir way of life as it flows along. (p. 37)

Adopting mainly the methodology of parti-cipant observation—described as “researchthat involves social interaction between theresearcher and informants in the milieu of thelatter, during which data are systematically andunobtrusively collected” (Taylor & Bogdan,1984, p. 15)—the researcher attempts to recordthe ongoing experiences of those observed intheir symbolic world. This research strategycommits the observer to learning to define theworld from the perspective of those studied andrequires that he or she gain as intimate an under-standing as possible of their way of perceivinglife. To achieve this aim, the field researchertypically supplements participant observationwith additional methodological techniques infield research, often including semistructuredinterviews, life histories, document analysis, andvarious nonreactive measures (Webb, Campbell,Schwartz, Sechrest, & Grove, 1981).

Most fieldwork projects are exploratory, thismeans that the researcher approaches thefield with certain special orientations, amongthem flexibility in looking for data and open-mindedness about where to find them. These areneeded to explore the phenomenon under studywhen relatively little is known about it. FollowingMax Weber’s model, the first step to be taken inthe scientific study of social life is to acquire anintimate, firsthand understanding (Verstehen) ofthe human acts being observed. It follows thatthe most efficient approach is to search for thisunderstanding wherever it may be found by anymethod that appears to bear fruit. The main goalof exploratory research is the generation ofinductively obtained generalizations about thefield. These generalizations are eventuallywoven into a “grounded theory” of the pheno-menon under consideration, the procedure forwhich is found in a series of publications byGlaser (1978), Glaser and Strauss (1967), andStrauss (1987).

4 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 4

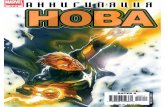

The left side of Figure A.1 indicates thatboth quantitative and qualitative data may begathered during exploration. Most exploratorystudies, however, are predominantly qualitative,possibly augmented in a minor quantitativeway by such descriptive statistics as indexes,percentages, and enumerations. As we come toknow better the phenomenon we have chosenfor examination, we move to the right acrossFigure A.1. That is, we come to rely less andless on exploration and more and more on pre-diction along the lines of hypotheses obtaineddeductively from the grounded theory. Thisprocess typically unfolds over the course ofseveral studies. It is paralleled by an expansionof the grounded theory through its application toan ever-wider range of phenomena and throughits internal development of an ever-growingnumber of generic concepts (Purs, 1987).

On the far right side of Figure A.1, we find awell-developed grounded theory about a reason-ably known, broad range of related phenomena.At this point concern is chiefly with enhancingthe precision of the theory, a process that ispursued commonly through prediction andquantification including a heavy reliance oninferential statistics. Even here, however, quali-tative data can sometimes play a role. Such data,for example, may help confirm certain hypothe-ses or bring to our attention through exploration

important recent changes in social process andstructure that the narrower focus of confirma-tion of hypotheses has led us to overlook.

Although descriptions and analyses of thevarious dimensions of the field research experi-ence have become more plentiful recently, it isunfortunate that the social aspects both underly-ing and shaping this experience have received solittle critical attention. These social aspects,which include feelings of self-doubt, uncertainty,and frustration, are both inherent in field researchand the basic stuff of which this methodologyconsists.

Field research is accompanied by a set ofexperiences that are, for the most part, unavail-able through other forms of social scientificresearch. These experiences are bound togetherwith satisfactions, embarrassments, challenges,pains, triumphs, ambiguities, and agonies, all ofwhich blend into what has been described asthe field research adventure (Glazer, 1972). It isdifficult to imagine a field project that does notinclude at least some of these features, howeverskilled and experienced the researcher. Anyoneundertaking field study for the first time—usually an undergraduate or a graduate student—encounters a mix of these feelings but, unlike theseasoned investigator, blames him- or herselffor the problem, seemingly a result solely ofinadequate preparation and experience.

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 5

Exploration-Description

(induction)

Exploration-

description

(induction)

Quantitative

Methods

Qualitative

Methods

Prediction-Hypothesis testing

(deduction)

Exploration-generic conception

(induction)

Prediction-

Model building

(deduction)

Prediction-

model building

(deduction)

Little-Known

Phenomena

Partially Known

Phenomena

Better-Known

Phenomena

Figure A.1 The Relationship of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 5

HISTORY OF FIELDWORK

The history of fieldwork as a set of researchtechniques, an approach to data collection, canbe related, in good measure, to the issues ofvalidity and reliability, ethics, and the study ofthe unfamiliar. In grappling with them, field-work procedure has gained in distinctivenessand respectability, and its place in the scientificprocess has been clarified.

Rosalie Wax (1971), who has written oneof the most extensive histories of fieldwork,points out that descriptive reporting of thecustoms, inclinations, and accomplishments ofother societies goes back almost to the origin ofwriting. From the Roman period on, travelershave been so fascinated with the cultural differ-ences they experienced that they have recordedtheir observations as a matter of interest tothemselves and their compatriots. And as worldpassage became easier in the late nineteenthcentury, so the accounts of “backward” peoplesmultiplied. Some of these “amateur” reports, ascontemporary anthropologists refer to them, areaccurate enough to be of scientific value.

While the travelers busied themselves writ-ing biased accounts of foreigners, educated menand sometimes women (e.g., lawyers, physicians,physical scientists, administrative officials)were gathering firsthand information on certainsections of their own societies with whichthey were unacquainted initially. In the earlytwentieth century Charles Booth, for example,combined statistical data with extensive inter-viewing and participant observation to completea vast study of the working people of London.In fact, several investigations were conducted inthe late nineteenth and early twentieth centuriesin England, France, and Germany that usedparticipant observation and interviews (some-times supplemented by questionnaires) toproduce data.

Bronislaw Malinowski (1922) was perhapsthe first social scientist to live in a preliteratecommunity for an extended period and to recordas objectively as possible what he saw. Hisintimate involvement in the daily lives of hissubjects is regarded as a turning point in thehistory of fieldwork procedure. Malinowski alsowrote detailed descriptions of how he gatheredhis data.

Several decades later, sociologist Robert Park(a former journalist) and anthropologist RobertRedfield turned the University of Chicago into acenter for participant observer-based fieldworkthat was without parallel anywhere in the world.During the 1920s, the first generation of sociol-ogists here concentrated on subjects such asthe hobo, the ghetto, the neighborhood, and thegang. Succeeding generations of students andfaculty examined, among others, French Canada,an Italian slum, juvenile delinquents, and gov-ernmental agencies (Blau, 1955), a mentalhospital (Goffman, 1961), and medical students(Becker, Geer, Hughes, & Strauss, 1961). UnlikeMalinowski, however, those who came underthe influence of Park and Redfield at Chicagowere expected to integrate their field data withthe ideas of Weber, Simmel, Dewey, and otherprominent social theorists of the day. Further-more, the fieldwork of this period maintained thestance of scientific objectivity, which startedwith the colonial period of world history and thedominance of natural science methods in worldintellectual circles. As Barnes (1963) put it:

The ethnographer took for granted that the obser-vations and records he made did not significantlydisturb the behavior of the people studied. In theclassical mechanics of the nineteenth century itwas assumed that physical observations could bemade without affecting the objects observed andin much the same way ethnographers assumedthat in their researches there was no direct feed-back from them to their informants. (p. 120)

Barnes goes on to state that times havechanged. Modern field research is apt to dealwith literate people who can read the resear-cher’s reports, write letters to influential author-ities, and perhaps sue. In response to this threatand others, ethics committees have emerged inmany universities, where they assess proposedsocial research for its possible unfavorableimpact on subjects. And modern field researchfrequently centers on topics within the investi-gator’s society. Thus the possibility must be facedthat some subjects, when in the researcher’s pres-ence, will not be candid in their behavior andconversations for fear that their actions and state-ments, which may be unacceptable to certainpeople, will become available to those persons.

6 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 6

“There may still be an exotic focus of study, butthe group or institution being studied is now seento be embedded in a network of social relations ofwhich the observer is an integral if reluctant part”(Barnes, 1963, p. 121).

Meanwhile, certain trends have forced fieldresearchers to clarify their position in the scien-tific process. The use of questionnaires gainedwidespread acceptance through the risingpopularity of public-opinion polling and itsclose association with the ideas of PaulLazarsfeld and Robert Merton (R. Wax, 1971,p. 40). Rigorous research designs, quantitativedata, statistical techniques, and at first mechan-ical and later electronic information processingbecame hallmarks of social scientific procedure,while fieldwork was regarded more and more asan old-fashioned and “softheaded” approach.

In other words, whereas one of the widelyacknowledged strengths of fieldwork has been itspotential for generating seminal ideas, its capa-city for effectively testing these ideas has beenincreasingly questioned. Field researchers helpedto confuse its role by claiming Znaniecki’s(1934) method of “analytic induction” as a modelof their procedure. In analytic induction, hypo-theses are generated not only from raw data butalso are tested by them. A lively debate sprang upsome time later over the logical possibility ofconducting both operations simultaneously(based on the same data) and over the generalutility of analytic induction (see Robinson, 1951;Turner, 1953).

More than 30 years elapsed after the publica-tion of Znaniecki’s book before social scientistssorted out the place of inductive hypothesis-generating procedure in the broader scientificprocess. Glaser and Strauss (1967) firmly estab-lished that no procedure can concurrently gener-ate and test propositions. The first requiresflexibility, unstructured research techniques,intuition, and detailed description; the seconduses control, structured techniques, precisions,and logical movement from premises to con-clusions. The “constant comparative method,” asGlaser and Strauss describe the approach, is aneffective means for generating hypotheses andgrounded theory.

We finally have learned that as our knowl-edge about an area grows—as hypothesesgrounded in direct field study begin to coalesce

into a theory about it—fieldwork and its lessstructured techniques fade into the background.At the same time, more controlled techniquescome into use (see Figure A.1). Today, somesocial science fields are largely or significantlyexploratory in their procedural orientation,among them anthropology, community psychol-ogy, symbolic interactionism, and classroomstudies.

Others, such as small group research andfamily sociology, generally appear to havepassed beyond this stage.

Although initial exploration has been thechief role of qualitative research, we are notclaiming that in its exploratory stage it isalways “preliminary” in its import. Exploratorystudies have been so effective as to have becomeclassics—for example, Whyte’s (1943/1981)StreetCorner Society or Goffman’s (1959) ThePresentation of Self in Everyday Life. In theseinstances and others, social science has subse-quently learned through more controlled studythat the initial observations were empiricallysound and theoretically significant. Glaser andStrauss (1967, pp. 234-235) advance threereasons why exploratory investigations often turnout to be the final research on a particular topic.First, the qualitative findings are taken by socialscientists to be definitive. Second, interest wanesin conducting further research on the phenome-non. Third, before researchers can mount morerigorous studies of it, the phenomenon haschanged considerably.

A parallel history of growing self-conscious-ness about the special status of fieldworkis evident in two ways: in the organizationaldevelopments that have come to surround it,and in its literature. Every year since 1984,McMaster University, the University of Waterloo,and more recently York University have spon-sored conferences on qualitative methods andresearch projects. Although more specialized,the annual University of Pennsylvania Ethno-graphy in Education Research Forum has beenaround even longer (since 1980). The Quali-tative Interest Group (QUIG) at the Universityof Georgia offered in early 1990 its third inter-national conference on qualitative research ineducation. Educationists were also instrumentalin starting in 1987 in Quebec the francophoneAssociation pour la recherche qualitative;

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 7

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 7

however, it embraces qualitative research in allfields. It is possibly the first association devotedexclusively to qualitative research.

Concerning self-consciousness about thespecial status of fieldwork as seen in the pro-gression of its literature, Junker (1960, p. 160)notes that in the first two decades of this centurythe publications of field researchers containedlittle about their problems and experiences. Hetraces the tendency to discuss these matters inthe final report, however briefly, to Robert andHelen Lynd’s study of Middletown. But it wasnot until after 1940 that theoretical treatmentsof fieldwork issues and experiences began tooccur with regularity. Even in 1960, Junker couldwrite that “full accounts are still rare, consideringthe large number of field studies published andstill coming off the presses” (pp 160-161).

Since then, however, candid descriptions offieldwork that frequently touch on the issues ofvalidity and ethics have become routine in mono-graphic reports. Several texts and readers devotedexclusively to this method also have beenproduced. Some of the most recent of these havebeen written or edited by Berg (1989), Emerson(1983), Hammersley and Atkinson (1983),Lofland and Lofland (1984), and Taylor andBogdan (1984). Since 1986 Sage Publicationshas published the Qualitative Research Methodsseries of short introductions to the methodo-logical tools of qualitative studies, and since 1977the Sociological Observations series of mono-graphs. Approximately two decades ago JohnLofland (1971, p. 131) urged researchers topresent detailed accounts of the social relationsand private feelings experienced in the field. Alsoof note are the two main journals for qualitativeresearch, the Journal of Contemporary Ethno-graphy (formerly Urban Life and Culture andthen Urban Life), founded in 1972, and Quali-tative Sociology, founded in 1978. Nonetheless,in sociology and especially anthropology, articleson qualitative methods and research projectsfrequently appear in many of the general andspecialty journals.

ISSUES IN FIELDWORK

Besides acquainting unseasoned field resear-chers with the nature of the experiences that

await them, there are three reasons why acollection of accounts is valuable. They are seenin the three issues traditionally consideredin methodological discussions of the fieldapproach that are affected by the nature of theresearcher’s experiences in gathering data:validity and reliability, ethics, and the study ofthe unfamiliar. Because field researchers arevirtually part of the data-collection process,rather than its external directors, their experi-ences there are critical.

Validity and Reliability

The problem of validity in field research con-cerns the difficulty of gaining an accurate ortrue impression of the phenomenon under study.The companion problem of reliability centers onthe replicability of observations; it rests on thequestion of whether another researcher withsimilar methodological training, understandingof the field setting, and rapport with the subjectscan make similar observations. In field researchthese two problems fall into the followingcategories:

(1) reactive effects of the observer’s presence oractivities on the phenomena being observed;

(2) distorting effects of selective perception andinterpretation on the observer’s part; and

(3) limitations on the observer’s ability to witnessall relevant aspects of the phenomena in ques-tion (McCall & Simmons, 1969, p. 78).

The experiences of the researcher bear onall three.

Reactive effects are the special behavioralresponses subjects make because the observeris in the setting, responses that are atypical forthe occasion. Webb and his colleagues (1981,pp. 49-58) treat four reactive effects that fre-quently invalidate social science data, two ofwhich—the guinea pig effect and role selec-tion—are germane here. In the first, subjects areaware of being observed and react by puttingtheir best foot forward; they strive to make agood impression. In the second, which is closelyrelated, they choose to emphasize one of severalselves that they sense is most appropriate giventhe observers presence.

8 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 8

Special reactive effects may take placewhen a researcher’s rational appearances fail(Johnson, 1975, pp. 155-160). Observers arehuman, too. At times they get angry, becomesympathetic, grow despondent, and are unableto hide these sentiments. Jean Briggs’s (1986,pp. 34-38) indignation at the Kapluna (white)fisherman who damaged a canoe owned by theEskimos she was studying resulted in subtleostracism that lasted three months. The validityof the data is certainly jeopardized, in somemeasure, by such outbursts. Perhaps, too, main-taining rationality when emotion is convention-ally expected produces the image of a researcherwho is callous or lifeless and should be treatedaccordingly.

Another condition under which reactiveeffects could blemish the quality of data is thedisintegration of trust between the observer andone or more subjects. Once the researcher hasfound or been placed in a role in the group beingstudied, whether that of observer or somethingmore familiar to its members, a certain degreeof trust develops whereby he or she is allowedto participate in many of their affairs. Behaviorof the observer that contradicts the belief that heor she belongs in that role may break the bondof trust. Still more unfortunate, it may suddenlycome to light that the observer is just that, anobserver, rather than a pure member—one ofthe chief hazards in operating as a concealedresearcher. This possibility haunted KathrynFox (1987) in her study of punk rockers. Sheknew that if her identity as a researcher becamegenerally known, she would effectively be deniedaccess to the local punk scene. This situationseverely limited her participation there.

Observers also selectively perceive and inter-pret data in different ways that ultimately andsometimes seriously bias their investigations.The most celebrated of these is “going native,”or so thoroughly embracing the customs andbeliefs of the focal group that one becomesincapable of objective work. Certain otherproblems bear mention as well. Johnson (1975,pp. 151-155) points out that the observer’sapprehension that commonly attends entry tothe field can slant the perception of eventsduring his or her early days there. Moreover, ourcommonsense assumptions about life are dis-turbed during these initial weeks, causing us to

see things that other people, with differentpresuppositions about everyday affairs, wouldmiss.

Special orientations towards subjects, whetherlove, hate, friendship, admiration, respect, or dis-like, also influence our views of these peopleand their behavior. One wonders what conse-quences the close bond between Doc andWilliam F. Whyte (1943/1981) or Tally andElliot Liebow (1967) had for the observers’ per-ceptions of these informants and the informants’social involvements. Undoubtedly there wereboth advantages and disadvantages to thesearrangements. Of equal importance are thedesires felt by many field researchers to helptheir subjects in some way. They face a profounddilemma, however, when the need for help is sogreat that it threatens the study itself by monopo-lizing the time the researcher has to commit to thelatter (Lofland & Lofland, 1984, p. 34).

The third category of validity and reliabil-ity problems deals with limitations on theobserver’s ability to witness all that is relevant tothe study. For example, Richard V. Ericson(1981, pp. 25-26) found in his study of detectivework that it appeared on certain occasions thatcases were assigned intentionally to anotherteam of detectives to which there was no fieldresearcher attached. On other occasions thedetective sergeant responsible for case assign-ments would give a case to a team with aresearcher because he believed the case wouldbe interesting to the researcher.

Taylor and Bogdan (1984, pp. 44-45) discussa related fieldwork predicament that can cut offresearchers from events of great importance tothem. Observers, having become established asindividuals who are knowledgeable about thelocal scene, may be called upon to mediate con-flict or advise on how to solve a problem. Thosewho follow this lead and try to help may findthemselves alienated from members of thegroup whose lives were affected unfavorably byor who were opposed to the suggested solution.

The status of the researcher may engenderstill another type of observational limitation.One thorny status problem, prevalent in anthro-pology and sociology, is the exclusiveness ofsex. Being male, for instance, tends to bar onefrom direct observation of female activities, asShaffir (1974, p. 43) discovered while studying

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 9

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 9

the Lubavitcher Chassidim of Montreal. He wasforced to accept different orders of data formales and females in that community. RosalieWax (1971, p. 46) describes the exclusivenessof certain age and sex categories she encoun-tered as a woman scientist who has worked inseveral different groups.

All research is subject to the problem of reli-ability and validity. Although they are commonto the experiment and the survey, they also arefound in fieldwork. The critics of fieldwork lackconfidence in the analysis of and conclusionsdrawn from field data. This sentiment hinges ontheir belief that the undisciplined procedures offieldwork enable researchers, to a greater degreethan practitioners of other methodologies, toinfluence the very situations they are studying,thereby flagrantly violating the canons of scien-tific objectivity.

A common feature of all social scienceresearch is the subjects’ response to the “demandcharacteristics” of the investigation (Orne, 1962;Rosenthal, 1970; Sherman, 1967).

Researchers in the social sciences are faced witha unique methodological problem: the very condi-tions of their research constitute an importantcomplex variable for what passes as the findingsof their investigations. . . . The activities of theinvestigator play a crucial role in the dataobtained. (Cicourel, 1964, p. 39)

In fieldwork, researchers’ very attempts toestablish rapport with the people they are study-ing may be achieved at the expense of a degreeof accuracy as to how they normally behave orpresent themselves in the situations beingobserved. Indeed, Jack Douglas (1976) argues,for these reasons and others, that traditionalmethods of field research must be discarded infavor of more penetrating or “investigative”procedures that permit access to these privatespheres of life. As Becker (1970, pp. 39-62) sopersuasively argues, however, in contrast to themore controlled methods of laboratory experi-ment and survey interviews, fieldwork is leastlikely to permit researchers to bias results tocorrespond with their expectations.

First, the people the field worker observes areordinarily constrained to act as they would have in

his absence, by the very social constraints whoseeffects interest him; he therefore has little chance,compared to practitioners of other methods, toinfluence what they do, for more potent forces areoperating. Second, the field worker inevitably, byhis continuous presence, gathers much more dataand . . . makes and can make many more tests ofhis hypotheses than researchers who use moreformal methods. (pp. 43-44)

One way to attack the validity problem is toplay back one’s observations to one’s subjectsin either verbal or written form. From the per-spective of the experience of fieldwork, thispractice tends to enhance rapport with subjects(assuming the observations are of interest tothem and of little threat) by casting them in theroles of local experts and helpful participantsin the research project. “Member validation” isone of several contributions that informantscan make.

Ethical Issues

Only part of the seemingly endless list ofethical issues that plague social scientists isgermane to the social experience of fieldwork.These issues are of three kinds: ethics of con-cealment, changes in research interests, andviolations of the researcher’s moral code. Theoft-discussed questions of what to write aboutthe group under study, how to protect confiden-tiality against legal proceedings, and the like areof greatest concern after leaving the field. Theyappear to play no significant role in the actualcollection of data.

Of the three kinds, the ethics of concealmenthas been examined most thoroughly in the pro-fessional literature. It has several facets, onebeing the issue of the covert observer, or socialscientific investigator whose professional aimsare unknown to the subjects. They take the indi-vidual for someone else, usually one of them.The majority of writers on this topic opposeconcealment (e.g., Davis, 1961; Erikson, 1965;Gold, 1958, pp. 221-222), though some scholarsargue the contrary (e.g., Douglas, 1976). Oneway in which this issue can affect the actualexperience of fieldwork is recounted by Wallis(1977), who secretly observed a Scientologygroup:

10 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 10

At the Scientology lodging house the problemwas equally difficult. The other residents withwhom I dined and breakfasted were commit-ted Scientologists and in a friendly way soughtto draw me into their conversations. I found it dif-ficult to participate without suggesting a commit-ment similar to their own, which I did not feel.Returning to the course material, I found as I pro-gressed that I would shortly have to convey—either aloud or by my continued presence—assentto claims made by Ron Hubbard, the movement’sfounder, with which I could not agree and of whichI could sometimes make little sense. (p. 155)

Even where the observer’s true role is known,ethical considerations may arise when there isconcealment of certain aspects of the project.Occasionally, the project’s very aims are keptsecret; Reece and Siegal (1986, pp. 104-108) pre-sent a fictive case along these lines and thenexplore its ethical implications. Or concealmentmay be more subtle, but no less questionable inthe eyes of some scientists, when data are gath-ered by means of a hidden tape recorder, inad-vertently overheard remarks, or intentionaleavesdropping. These clandestine methods addtension to the conduct of fieldwork becausethere is always the risk that what is hidden willsomehow be uncovered. Finally, individualresearchers may question the propriety of con-cealing opinions that are diametrically opposedto those held by their subjects. Howard Newby(1977, p. 118), for example, suffered pangs ofconscience of this sort when as a liberal univer-sity student he interviewed conservative farmworkers about their political attitudes. On arelated theme, Yablonsky (1965, p. 72) sees theresearcher’s failure to moralize, when accom-panied by an intense interest in deviant life styles,as subtle encouragement of the subject’s aberrantbehavior.

Changes in research interests are inevitablein field study, where one of the central aims isto discover data capable of generating originaltheory. Johnson (1975, p. 58) notes how inves-tigators may gain entry to a field setting by stat-ing a particular set of interests, only to findthemselves in a moral dilemma because theirobservations have spawned new interests, onesthat the sponsors had no opportunity to con-sider. To make things worse, these new interestsmay touch on sensitive matters, where formal

permission for observation or interviewingmight never be granted.

Then there is the question of the ethical con-flict suffered by field researchers who feel com-pelled to engage in, or at least witness, illegalactivities. Should such activities be reported?The agency whose permission has made theresearch possible may expect this will be done.Should researchers try to maintain or strengthenrapport with their subjects by participating inunlawful events when invited to do so? Polsky(1967/1985, p. 127), who systematically obser-ved criminals in their natural habitat, says thatthis is up to the individual investigator but that, inthe study of criminals anyway, one should makeclear what one is prepared to do and see andnot to do and see. William Whyte (1943/1981,pp. 313-317) got caught in the ethical dilemma ofwhether to vote in place of another man in amayoralty election.

Although all field researchers are faced withethical decisions in the course of their work, areview of the fieldwork literature reveals thatthere is no consensus concerning the researcher’sduties and responsibilities either to those studiedor to the discipline itself. As Roth (1960) has soaptly argued, the controversy between “secretresearch” and “nonsecret research” is largelymisguided, for all research is secret in some way.A more profitable line of investigation is to focuson “how much secrecy shall there be with whichpeople in which circumstances” (p. 283). Mostfield researchers hold that some measure ofresponsibility is owed the people under study,though the extent of this conviction and its appli-cation are left to each researcher’s conscience.

Studying the Unfamiliar

Dealing with the unfamiliar is bound toproduce at least some formative experiences. Infield investigations the use of unstructuredprocedures, the pursuit of new propositions, andthe participation in strange (for the scientist)activities are the stuff of which memorableinvolvements are made.

Unlike controlled studies, such as surveys andexperiments, field studies avoid prejudgment ofthe nature of the problem and hence the use ofrigid data-gathering devices and hypothesesbased on a priori beliefs or hunches concerning

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 11

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 11

the research setting and its participants. Rather,their mission is typically the discovery of newpropositions that must be tested more rigorouslyin subsequent research specially designed forthis purpose. Hence field researchers alwayslive, to some extent, with the disquieting notionthat they are gathering the wrong data (e.g.,Gans, 1968, p. 312), that they should be observ-ing or asking questions about another event orpractice instead of the present one. Or they arebewildered by the complexity of the field settingand therefore are unable to identify significantdimensions and categories that can serve tochannel their observations and questions. Thesefeelings of uncertainty that accompany open-ended investigation tend, however, to diminishas the investigator grows more familiar with thegroup under study and those of its activities thatbear on the research focus.

Blanche Geer (1964) describes the confusionof her first days in the field as she set out toexamine the different perspectives on academicwork held by a sample of undergraduates:

Our proposal seems forgotten. Of course, therewere not enough premedical students at the pre-views (summer orientation for freshmen) for meto concentrate on them. To limit myself to ourbroader objective, the liberal-arts college student,was difficult. The previewers did not group them-selves according to the school or college of theUniversity they planned to enter. Out of ordinarypoliteness . . . I found myself talking to prefresh-men planning careers in engineering, pharmacy,business, and fine arts, as well as the liberal arts.Perhaps it is impossible to stick to a narrow objec-tive in the field. If, as will always be the case,there are unanticipated data at hand, the fieldworker will broaden his operations to get them.Perhaps he includes such data because they willhelp him to understand his planned objectives, buthe may very well go after them simply because,like the mountain, they are there. (p. 327)

The requirement that a researcher discoversomething only increases the anxiety of field-work. Nowhere does originality come easily.The field experience does offer a kaleidoscopeof contrasts between the observer’s routineworld and that of the subjects. New patterns ofthought and action flash before the observer’seyes. But the question is always: Are these of

any importance for science? Researchers notethese contrasts and often virtually everythingelse they perceive. Nevertheless, the ultimategoal is conceptual. One strives to organize thesenovel perceptions into a grounded or inductivetheory, which is done to some extent while stillin the field. Some of the generalizations thatconstitute the emerging theory are born fromon-the-spot flashes of insight. Herein lies the artof science. And these insightful moments can beamong the most exciting of the fieldwork expe-rience, while their absence can be exasperating,if not discouraging.

As if unstructured research procedure andobligatory discovery were not enough, fieldinvestigators must also be ready to cope withunfamiliar events. Furthermore, they must learnnew ways of behaving and possibly new skills,the mastery of which are crucial for success intheir projects. Powdermaker (1968) describesthis problem for the field anthropologist:

During the first month or so the field workerproceeds very slowly, making use of all his sen-sory impressions and intuitions. He walks warilyand attempts to learn as quickly as possible themost important forms of native etiquette andtaboos. When in doubt he falls back on his ownsense of politeness and sensitivity to the feelingsof others. He likewise has to cope with his ownemotional problems, for he often experiencesanxieties in a strange situation. He may be over-whelmed by the difficulties of really getting“inside” an alien culture and of learning anunrecorded or other strange language. He maywonder whether he should intrude into the privacyof people’s lives by asking them questions. Fieldworkers vary in their degree of shyness, but mostpeople of any sensitivity experience some feelingsof this type when they first enter a new fieldsituation. (p. 419)

MARGINALITY

If there is one especially well-suited adjectivethat describes the social experiences of field-work, it is marginality. Field researchers andtheir activities are marginal in several ways. Forone, field research—because of its emphasison direct human contact, subjective understand-ing of others’ motives and wants, and broad

12 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 12

participation in their daily affairs—is closer tothe humanities than most forms of social scien-tific research. Although structured data collectionis now the most traveled methodological route inmany social sciences, field researchers are ridingoff in a different direction. For this they arescorned by many positivists, who see fieldresearch as a weak science. From the humanists’perspective, however, it is still too scientific,owing to its concern with validity, testable hypo-theses, replicability, and the like. The public, whomight be expected to take a neutral stand in thisintellectual debate, sometimes appears to haveembraced the stereotype that good social scienceis characterized only by quantitative rigor. Thusit occasionally happens that field researchers alsohave to convince even their subjects and sponsorsthat theirs is a legitimate approach for the prob-lem at hand.

Yet the field researcher who is identified asan atypical social scientist has an advantage.For here is a scientist who is viewed by groupmembers as interested enough in them and theiractivities to maintain extensive direct contactinstead of relying solely or chiefly on such sub-stitutes as questionnaires and measurementscales. Many subjects appreciate this specialeffort. They seem to know that their lives aretoo complicated to be studied accurately andadequately by structured means alone. By thesame token, it is to be expected that fieldresearchers will make some subjects uneasy bytheir tendency to plumb the group’s dark secrets.

Field researchers are also marginal in theirown professions (except in anthropology).Recall Lofland’s (1976, p. 13) observation thatmany social scientists are unsuited for engagingin field study. Being rather asocial, reclusive,and occasionally abrasive, they would fail togain entrance to the setting to be examined or,if they somehow succeeded, they would fail tomaintain the level of rapport upon which goodfield research depends. Social scientists whohave the requisite interpersonal skills to do field-work are a minority; providing they discovertheir talents, they find occupational fulfillmentin ways most of their colleagues see as strange orexotic.

Once in the field, all participant observers, ifthey are known as such to their subjects, aremore or less marginal to their subjects’ world.

The former never quite belong, especially whilethe research is getting under way—a fact that ismade amply clear time and again. As Hughes(1960) argues, even though the sociologistmight report observations made as a member ofthe group under study, “the member becomessomething of a stranger in the very act of objec-tifying and reporting his experiences” (p. ix). Ina similar vein, Freilich (1970), writing aboutanthropologists, cautions against the commondesire among researchers to become a native:

Irrespective of what role he assumes, the anthro-pologist remains a marginal man in the commu-nity, an outsider. No matter how skilled he is inthe native tongue, how nimble in handling strangesocial relationships, how artistic in performingsocial and religious rituals, and how attached he isto local beliefs, goals, and values, the anthropo-logist rarely deludes himself into thinking thatmany community members really regard him asone of them. (p. 2)

From the researcher’s standpoint there arehumbling experiences inherent in this kind ofmarginality. Lofland (1976, p. 14) points outthat one must admit to laymen that one is igno-rant, though willing to learn. Such an admissionis incongruent with the self-image of savant,of dignified university professor, of learnedPh.D. As a field researcher, one is a mere studentin need of particular instruction or generalsocialization.

What is worse, subjects have been known totake advantage of this situation and put on ormislead the observer about aspects of their livesof interest to the study (e.g., Visano, 1987,p. 67). Field researchers must be alert to suchdeception but be prepared to take it in goodstride. Nonetheless, being the object of a put-on, while it adds zest to the subjects’ routine,frequently is embarrassing to the “mark”(Stebbins, 1975).

And fieldwork, even when conducted in theresearcher’s own community, has been knownto become all-absorbing, leaving time only forabsolutely mandatory family and work activi-ties. Marginality is the best characterizationof the committed social scientist, who spendspractically every waking minute riding withpolice or observing juvenile gangs. As with

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 13

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 13

professionals in any occupation, the linebetween work and leisure is sometimes erasedfor field researchers, which casts them in astrange light when viewed from the perspectiveof a leisure-oriented society.

On balance, marginality, despite its draw-backs, seems to breed a peculiar strain of moti-vation among committed field researchers.Being atypical in one’s profession, to the extentthat such a condition is free of stigma, has thepotential appeal of salutary visibility, of beingcommendably different. Field researchers havestories to tell about their data-collection exploitsthat enchant students and colleagues, most ofwhom have no such accounts to swap. Fieldresearchers have “been around” in a way seldommatched by the run-of-the-mill social scientist.They have gained in personal sophisticationthrough contact with other cultures andlifestyles and through solving thorny interper-sonal problems in the course of completing theirprojects.

CONCLUSION

As most field researchers would admit, the so-called rules and canons of fieldwork frequentlyare bent and twisted to accommodate the parti-cular demands and requirements of the fieldworksituation and the personal characteristics of theresearcher. The following observations reflectthis view clearly and accurately:

As every researcher knows, there is more to doingresearch than is dreamt of in philosophies ofscience, and texts in methodology offer answersto only a fraction of the problems one encounters.The best laid research plans run up against unfore-seen contingencies in the collection and analysisof data; the data one collects may prove to havelittle to do with the hypotheses one sets out to test;unexpected findings inspire new ideas. No matterhow carefully one plans in advance, research isdesigned in the course of its execution. The fin-ished monograph is the result of hundreds of deci-sions, large and small, made while the research isunderway and our standard texts do not give usprocedures and techniques for making these deci-sions. . . . I must take issue with one point . . . thatsocial research being what it is, we can neverescape the necessity to improvise, the surprise of

the unexpected, our dependence on inspiration.. . . It is possible, after all, to reflect on one’s dif-ficulties and inspirations and see how they couldbe handled more rationally the next time around.In short, one can be methodical about matters thatearlier had been left to chance and improvisationand thus cut down the area of guess work.(Becker, 1965a, pp. 602-603)

The sociological enterprise of theory andresearch has been presented as an idealizedprocess, immaculately conceived in design andelegantly executed in practice. My discussions oftheory, measurement, instrumentation, samplingstrategies, resolutions of issues of validity, andthe generation of valid causal propositions byvarious methods proceeded on an assumption.This assumption was that once the proper ruleswere learned, adequate theory would be forth-coming. Unfortunately, of course, this is seldomthe case. Each theorist or methodologist takesrules of method and inference and molds them tofit her particular problem—and personality.(Denzin, 1989, p. 249)

REFERENCES

Adler, P.A. (1985). Wheeling and Dealing. New York: Columbia University Press.

Adler, P.A., & Adler, P. (1987). Membership Rolesin Field Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Barnes, J.A. (1963). Some Ethical Problems inModern Fieldwork. British Journal of Sociology,14, 118-134.

Becker, H.S. (1963). Outsiders: The Sociology ofDeviance. New York: Free Press.

Becker, H.S. (1965a). Review of Sociologists at Work.American Sociological Review, 30, 602-603.

Becker, H.S. (1970). Sociological Work: Method andSubstance. Chicago: Aldine.

Becker, H.S. & Geer, B., Hughes, E.C., Strauss, A.L.(1961). Boys in White. Chicago: University ofChicago Press.

Berg, B.L. (1989). Qualitative Research Methods.Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Blau, P.M. (1955). The Dynamics of Bureaucracy.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic Interactionism.Berkeley: University of California Press.

Briggs, J.L. (1986). Kapluna Daughter. In P. Golde(Ed.), Women in the Field (pp. 19-46, 2nd ed.).Berkeley: University of California Press.

14 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 14

Cicourel, A.V. (1964). Method and Measurement inSociology. New York: Free Press.

Davis, F. (1961). Comment on “Initial Interaction ofNewcomers in Alcoholics Anonymous.” SocialProblems, 8, 364-365.

Denzin, N.K. (1989). The Research Act (3rd ed.)Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Douglas, J.D. (1976). Investigating Social Research:Individual and Team Field Research. BeverlyHills, CA: Sage.

Emerson, R.M. (Ed.). (1983). Contemporary FieldResearch: A Collection of Readings. Boston:Little, Brown.

Ericson, R.V. (1981). Making Crime: A Study ofDetective Work. Toronto, Ont: Butterworths.

Erikson, K.T. (1965). A Comment on DisguisedObservation in Sociology. Social Problems,14, 366-373.

Fox, K.J. (1987). Real Punks and Pretenders. Journalof Contemporary Ethnography, 16, 344-370.

Freilich, M. (1970). Toward a Formalization of Field-work. In M. Freilich (Ed.), Marginal Natives.New York: Harper & Row.

Friedman, R.A. (1989). Interaction Norms as Carriersof Organizational Culture: A Study of LabourNegotiations at International Harvester. Journalof Contemporary Ethnography, 18, 3-29.

Gans, H. (1968). The Participant Observer as aHuman Being: Observations on the PersonalAspects of Fieldwork. In H.S. Becker, B. Greer,D. Reisman, & R. Weiss (Eds.), Institutions andthe Person (pp. 300-317). Chicago: Aldine.

Geer, B. (1964). First Days in the Field. InP. Hammond (Ed.), Sociologists at Work(pp. 322-344). New York: Basic Books.

Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The Discoveryof Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine.

Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (1968). Time for Dying.Chicago: Aldine.

Glazer, M. (1972). The Research Adventure: Promiseand Problems of Fieldwork. New York: RandomHouse.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self inEveryday Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the SocialSituation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates.Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Golde, P. (1986). Odyssey of Encounter. In P. Golde(Ed.), Women in the Field: AnthropologicalExperiences (pp. 67-96, 2nd ed.). Berkeley:University of California Press.

Gold, R.L. (1958). Roles in Sociological Observations.Social Forces, 36, 217-223.

Hammersley, M. & Atkinson, P. (1983). Ethnography:Principals in Practice. London, UK: Tavistock.

Hughes, E.C. (1960). Introduction: The Place ofFieldwork and Social Science. In B.H. Junker(Ed.), Fieldwork: An Introduction to the SocialSciences (pp. iii-xiii). Chicago: University ofChicago Press.

Johnson, J.M. (1975). Doing Field Research. New York: Free Press.

Junker, B.H. (1960). Fieldwork: An Introductionto the Social Sciences. Chicago: University ofChicago Press.

Liebow, E. (1967). Tally’s Corner. Boston: Little,Brown.

Lofland, J.A. (1971). Analyzing Social Settings: AGuide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis.Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Lofland, J.A. (1976). Doing Social Life: TheQualitative Study of Human Interaction inNatural Settings. New York: John Wiley.

Lofland, J.A. & Lofland, L. (1984). AnalyzingSocial Settings: A Guide to QualitativeObservation and Analysis (2nd ed.). Belmont,CA: Wadsworth.

Malinowski, B. (1922). The Argonauts of theWestern Pacific. London, UK: Routledge.

McCall, G.J. & Simmons, J.L. (Eds). (1969). Issuesin Participant Observation. Reading, MA:Addison-Wesley.

Newby, H. (1977). In the Field: Reflection on theStudy of Suffolk Farm Workers. In C. Bell &H. Newby (Eds.), Doing Sociological Research(pp. 108-129). London, UK: Allen & Unwin.

Orne, M.T. (1962). On the Social Psychology of thePsychological Experiment. American Psycho-logist, 17, 776-783.

Polsky, N. (1985). Hustlers, Beats, and Others.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Originalwork published 1967)

Powdermaker, H. (1968). Fieldwork. In D.L. Sills(Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the SocialSciences (Vol. 5, pp. 418-424). New York:Macmillan.

Prus, R. (1987). Generic Social Processes: MaximizingConceptual Development in EthnographicResearch. Journal of Contemporary Ethno-graphy, 16, 250-293.

Reece, R.D., & Siegal, H.A. (1986). Studying People:A Primer in the Ethics of Social Research.Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

Robinson, W.S. (1951). A Logical Structure ofAnalytic Induction. American SociologicalReview, 16, 812-818.

Rosenthal, R. (1970). Interpersonal Expectations. InR. Rosenthal & R. Rosnow (Eds.), Sources ofArtifact in Social Research (pp. 181-277). New York: Academic Press.

Introduction to Qualitative Methods • 15

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 15

Roth, J. (1960). Comments on Secret Observation.Social Problems, 9, 283-284.

Scott, G.G. (1983). The Magicians: A Study ofthe Use of Power in a Black Magic Group. New York: Irvington.

Shaffir, W.B. (1974). Life in a Religious Community.Toronto: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Shaffir, William, Marshall, Victor, & Haas, J.(1980). Competing Commitments: UnanticipatedProblems of Field Research. Qualitative Socio-logy, 2, 56-71.

Sherman, S.R. (1967). Demand Curves in anExperiment on Attitude Change. Sociometry,30, 246-261.

Stebbins, R.A. (1975). Putting People On: Deceptionof Our Fellow Man in Everyday Life. Sociologyand Social Research, 59, 189-200.

Strauss, A.L. (1987). Qualitative Analysis for SocialScientists. New York: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Taylor, S. J. & Bogdan, R. (1984). Introductionto Qualitative Research Methods: TheSearch for Meaning (2nd ed). New York: JohnWiley.

Turner, R.H. (1953). The Quest for Universals inSociological Research. American SociologicalReview, 18, 604-611.

Visano, L.A. (1987). This Idle Trade: The Occu-pational Patterns of Male Prostitution. Concord,Ont: VitaSana.

Wallis, R. (1977). The Moral Career of a ResearchProject. In C. Bell & H. Newby (Eds.), DoingSociological Research (pp. 149-167). London,UK: Allen & Unwin.

Wax, R.H. (1952). Field Methods and Techniques:Reciprocity as a Field Technique. HumanOrganization, 11, 34-37.

Wax, R. H. (1971). Doing Fieldwork: Warnings andAdvice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Webb, E.J., Campbell, D.T. Schwartz, R.D. Sechrest,Lee, & Grove, J.B. (1981). NonreactiveMeasures in the Social Science (2nd ed.).Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Wharton, C.S. (1987). Establishing Sheltersfor Battered Women. Qualitative Sociology, 10,146-163.

Whyte, W.F. (1981). Street Corner Society. Chicago:University of Chicago Press. (Original workpublished 1943)

Yablonsky, L. (1965). Experiences with the CriminalCommunity. In A. Gouldner & S.M. Miller(Eds.), Applied Sociology (pp. 55-73). New York:Free Press.

Znaniecki, F. (1934). The Method of Sociology. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.

16 • QUALITATIVE APPROACHES TO CRIMINAL JUSTICE

01-Pogrebin.qxd 9/24/02 4:37 PM Page 16