November/December 2012 Vol 37, No 6 - NZIIA...E-mail: [email protected] Subscriptions: New...

Transcript of November/December 2012 Vol 37, No 6 - NZIIA...E-mail: [email protected] Subscriptions: New...

InternationalNew Zealand

eviewRNovember/December 2012 Vol 37, No 6

CHINA–NEW ZEALAND AT 40 Micronesia South-east Asia

NEW ZEALAND INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

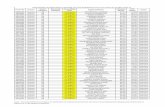

Corporate MembersAir New Zealand LimitedANZCO Foods LimitedAsia:NZ FoundationAustralian High CommissionBeef + Lamb New Zealand LtdBusiness New ZealandCatalyst IT LtdCentre for Defence & Strategic Studies, Massey UniversityDepartment of ConservationDepartment of LabourDept of the Prime Minister & CabinetFonterra Co-operative GroupGallagher Group LtdHQ New Zealand Defence ForceLandcorp Farming LtdLaw CommissionMinistry for the EnvironmentMinistry of Agriculture & ForestryMinistry of Defence

Ministry of Economic DevelopmentMinistry of EducationMinistry of Foreign Affairs &TradeMinistry of JusticeMinistry of Science & InnovationMinistry of Social DevelopmentMinistry of TransportNew Zealand Customs ServiceNew Zealand PoliceNew Zealand Trade & EnterpriseNew Zealand United States CouncilReserve Bank of New ZealandSaunders UnsworthScience New Zealand IncState Services CommissionStatistics New ZealandThe TreasuryVictoria University of WellingtonWellington Employers Chamber of Commerce

Institutional MembersAGMARDTApostolic NunciatureBritish High CommissionCanadian High CommissionCentre for Strategic StudiesCouncil for International DevelopmentCullen - The Employment Law FirmDeloitteEmbassy of CubaEmbassy of FranceEmbassy of IsraelEmbassy of ItalyEmbassy of JapanEmbassy of MexicoEmbassy of SpainEmbassy of SwitzerlandEmbassy of the Argentine RepublicEmbassy of the Federal Republic of GermanyEmbassy of the Federative Republic of BrazilEmbassy of the Islamic Republic of IranEmbassy of the People’s Republic of ChinaEmbassy of the PhilippinesEmbassy of the Republic of ChileEmbassy of the Republic of IndonesiaEmbassy of the Republic of KoreaEmbassy of the Republic of PolandEmbassy of the Republic of TurkeyEmbassy of the Russian Federation

Embassy of the United States of AmericaHigh Commission for MalaysiaHigh Commission for PakistanHigh Commission of IndiaHigh Commission of Papua New GuineaIndependent Police Conduct AuthorityNew Zealand Red CrossNZ China Friendship Society - Wellington BranchNZ Horticulture Export Authority

Political Studies Department, University of AucklandRoyal Netherlands EmbassyRoyal Thai EmbassySchool of Linguistics & Applied Language Studies, VUWSingapore High CommissionSoka Gakkai International of NZSouth African High CommissionStandards New Zealand

Tertiary Education CommissionThe Innovative Travel Co.LtdUnited Nations Association of NZVolunteer Service Abroad (Inc)World Vision New Zealand

New Zealand International Review1

New Zealand

International

Review

Managing Editor: IAN McGIBBONCorresponding Editors: STEPHEN CHAN (United Kingdom), STEPHEN HOADLEY (Auckland)Book Review Editor: ANTHONY SMITHEditorial Committee: ANDREW WEIRZBICKI (Chair), ROB AYSON, BROOK BARRINGTON, BOB BUNCH, GERALD McGHIE, MALCOLM McKINNON, JOSH MITCHELL, ROB RABEL, SHLINKA SMITH, JOHN SUBRITSKY, ANN TROTTER, JOCELYN WOODLEYPublisher: NEW ZEALAND INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRSTypesetting/Layout: LOVETT GRAPHICSPrinting: THAMES PUBLICATIONS LTD

New Zealand International Review is the bi-monthly publication of the New Zealand Institute of Affairs. (ISBN0110-0262)Address: Room 507, Railway West Wing, Pipitea Campus, Bunny Street, Wellington6011Postal: New Zealand Institute of International Affairs, C/- Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140Telephone: (04) 463 5356Website: www.vuw.ad.nz/nziia. E-mail: [email protected]: New Zealand $47.00 (incl GST/postage). Overseas $84.00 (Cheques or money orders to be made payable to the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs)

The views expressed in New Zealand International Reviewnon-partisan body concerned only to increase understanding and informal discussion of international affairs, and especially New Zealand’s involvement in them. By permission of the authors the copyright of all articles appearing in New Zealand International Review is held by the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs

2 China and New Zealand at forty: what next? Michael Powles reflects on the evolving Sino-New Zealand relationship and suggests that skill

will be needed in taking advantage of the opportunity it offers.

5 A strengthening China–New Zealand link John Key reflects on the 40 years of diplomatic relations between China and New Zealand and considers possibilities for the future.

8 A cautious start Paul Bellamy reflects on the early years of New Zealand–North Korea relations.

12 Stoking the engine of growth Tim Groser discusses the Trans-Pacific Partnership proposal and New Zealand’s export future.

John Goodman reflects on the experience of the four states of Micronesia in dealing with the problems of modernity.

21 Benign neglect: New Zealand, ASEAN and South-east Asia Andrew Butcher comments on the findings of a recent survey of New Zealanders’ awareness of

ASEAN nations.

24 CONFERENCE REPORT China–New Zealand ties: a timely focus Brian Lynch reports on a symposium held recently in Wellington.

28 BOOKS Mark N. Katz:Leaving Without Losing: The War on Terror after Iraq and Afghanistan (Anthony

Smith). Sanoussi Bilal, Philippe de Lombaerde, and Dianna Tussie: Assymetric Trade Negotiations

(Stephen Hoadley). Jian Yang: The Pacific Islands in China’s Grand Strategy: Small States, Big Games (Michael Powles). Damien Fenton: To Cage the Red Dragon: SEATO and the Defence of Southeast Asia, 1955–

1965 (Mark Pearson).

32 INSTITUTE NOTES

33 INDEX TO VOLUME 37

November/December 2012 Vol 37, No 6

NovDec issue 2012.indd 1 11/10/12 12:35 PM

New Zealand International Review2

Achieving a relationship with China as beneficial to New Zealand as the relationship we have today may be one of our most signif-icant overseas achievements. New Zealand leaders tend to high-light the dramatic economic benefit it has brought New Zealand. They could point as well to the contribution ethnic Chinese have made to New Zealand’s growth as a nation and the richness added by Chinese culture.

For their part, Chinese leaders point to New Zealand’s value to China, particularly through the oft-quoted ‘four firsts’, reflect-ing New Zealand’s support for China when it first sought mem-bership of the World Trade Organisation, our recognition of Chi-na’s status as a market economy, our entry into bilateral free trade negotiations and, finally, our being the first developed country to conclude a full free trade agreement with Beijing. And today access to New Zealand’s primary products is clearly important.

But for how long is this mutually advantageous relationship likely to continue?

The world has changed since New Zealand promoted in 1997 China’s membership of the WTO and demonstrated nearly a dec-ade ago that a small Western country could handle a complex free trade negotiation with Beijing. China today is much more inte-grated into global systems and better able than it was to negotiate in its own right variations in the rules to suit its own interests.

Looking ahead, New Zealand will no doubt want to continue benefiting from a co-operative relationship with a prosperous and growing China. But will it still be worth China’s while to co-oper-ate with New Zealand? A more powerful China may have much less need of the kind of small country support it valued so highly a decade and more ago.

When political and international observers first began to notice the developing China/New Zealand relationship, the re-spected Hong Kong columnist Frank Ching, writing in the South China Morning Post in 2006, dubbed the two countries ‘The Odd Couple’.1 To Ching, New Zealand’s support for China’s member-

China and New Zealand at forty: what next?

ship of the WTO was vitally important and led Beijing to agree to begin negotiations on a free trade agreement. Ching commented: No doubt, China appreciates New Zealand’s independent

foreign policy, having ended its alliance with the United States in the 1980s [sic].... Apart from economic relations, China and New Zealand are also developing cultural and ed-ucational ties.... Beijing, it appears, wants to ensure that its excellent relations with New Zealand will be longstanding.

New Zealand will certainly hope so. What we do have is an excel-lent foundation for a continuing relationship. But even a founda-tion as excellent as this one must diminish in lustre as time passes.

Hard work Of course, New Zealand has long been conscious that, as a com-paratively small and inconsequential international player, it has to be prepared to do the hard work in most bilateral relationships. Fighting off irrelevance and gaining favourable attention in major capitals are hard but essential tasks if we are to have any hope of influence.

Today the challenge for New Zealand has escalated. For the whole of its existence since British colonisation, we have been a part, albeit a very small part, of a predominant ‘anglosphere’. This has often made it easy for us to exercise more influence with major English-speaking powers than would normally be possible for a country of our size and power. We could emulate the flea who would whisper in the elephant’s ear, ‘My, how this bridge quakes when we great creatures cross.’ That kind of cozy cultural relation-ship does not exist with today’s rising major power.

The challenge for us now is to devise and pursue new policies based on the solid foundations we have built over the past 40 years. First, there needs to be a major effort to encourage greater knowledge and understanding within New Zealand of China and its culture. Then bilaterally we need new policies, consist-ent with New Zealand’s core national interests and the princi-ples that we have always sought to represent overseas, that can bring more value to our relations with Asia in general and China in particular. Logic would point to these being priority policy is-

Frank Ching

New Zealand has developed an enormously valuable relationship with China, resulting in the only free trade agreement China has concluded with a developed country. But China’s growing global

utation for global independence, particularly as a friend rather than ally of either of the world’s

NovDec issue 2012.indd 2 11/10/12 12:36 PM

New Zealand International Review3

sues for us at present yet, strangely, there seems little debate about them.

New Zealand does have a long history of strong relations with numbers of Asian countries, in addition to China. Indeed, we have backed the aspirations of the major countries of South-east Asia, in particular, and been a strong supporter of ASEAN since its formation. With some countries what is required is ‘more of the same’. While New Zealand, like Australia, is accustomed to regular policy consultations with the major countries of East Asia, we should consider seeking to increase the frequency and serious-ness of these. Richard Woolcott, former secretary of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, is reported to have said that Canberra ought to consult Jakarta ‘the way we consult Wash-ington’.2

Traditional imageInstead, according to Terence O’Brien, our 2010 defence white paper reinforces the older traditional last century image of New Zealand as a

diminutive extension of a distant Atlantic-centred world. The White Paper pinpoints the countries of the so-called Anglo-sphere — the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia — as the permanent security partners for this coun-try.

The paper does not address how the former comfortable symmetry between New Zea-

land’s security and prosperity interests is now being conclu-sively changed by the successful advance of East Asia.... It does not propose how New Zealand defence links with East Asian governments might be enhanced as a reflection of im-portant change.

O’Brien suggests there is surely scope for serious pursuit of joint deployment possibilities with Asian partners in order to reflect the region’s increasing importance to New Zealand. He points out that with New Zealand’s forthcoming bid for election to the Secu-rity Council and the significant experience of several Asian powers in UN peacekeeping, joint deployments could valuably be made in the field of UN peace support.3 China today contributes more troops to UN peacekeeping than any other permanent member of the Security Council.

A new ‘first’ for China and New Zealand was created in Ra-rotonga at the time of the recent Pacific Islands Leaders’ Forum when the two governments agreed to jointly sponsor a project with the Cook Islands to construct a new water mains system on Rarotonga. Prime Minister John Key hailed this as ‘an example of how we can work together to get the most benefit from our aid programmes in the Pacific’. China’s willingness to break with

precedent and work co-operatively with another donor will be regarded by many as a significant breakthrough. It will also be tak-en as a sign that while some donor governments, including ones with close relations with New Zealand, are unenthusiastic about China’s aid in the Pacific, New Zealand is happy to be seen to be a partner with China in delivering aid in the region. Perhaps this precedent can be followed in other areas as well.

In the trade and economic field, it will be important that New Zealand continues to support Asian initiatives. Although the cur-rent Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations do not at the moment include China, Trade Minister Tim Groser supports China’s in-volvement and it will be important New Zealand maintains this position. A regional free trade agreement is also on the agenda for the ASEAN plus Six group, including China (and New Zealand) but not the United States. It would be harmful to New Zealand’s interests if the issue of the appropriate vehicle for regional free trade should be caught up in US/China competition.

Most important, New Zealand has benefited enormously from being seen to be an independent player internationally. It was an important factor in China’s perception of New Zealand as the relationship developed.4 It is hard to imagine China giving such support to a New Zealand which abandoned even the claim to independence in foreign policy. Yet New Zealand today has been described as adopting the status of a ‘de facto ally of the United States’.5 If this were to reach the point, directly or incrementally, that New Zealand was seen by Beijing as supporting a US-led attempt to contain China or curb its rise, our relations with China would obviously be very seriously harmed. Being a friend of both major powers, but taking care not to be seen to be permanently aligned to either, will continue to be crucially important.

Our relationship with Australia, New Zealand’s most impor-tant, requires and deserves special treatment, not least as we define and pursue the New Zealand national interest in relation to Chi-na. The excellent Centre for Strategic Studies discussion paper by Chris Elder and Robert Ayson China’s Rise and New Zealand’s In-terests6 makes the point that it is New Zealand’s relationship with Australia that requires the most careful handling in this regard. The authors suggest ‘considerable finesse’ will be needed. While not spelt out so bluntly, the paper suggests that, in relation to China, New Zealand should continue, but not necessarily allow itself to be limited by, close consultation with Australia.

NovDec issue 2012.indd 3 10/10/12 2:24 PM

New Zealand International Review4

The CSS paper also discusses the challenge for New Zealand in seeking ‘to manage the competing claims and values of China and the United States’. This, too, will require finesse. For a start, it will be important that we New Zealanders form sensible and rational views of the intentions of China and, for that matter, the United States in our part of the world. Some observers highlight what they believe to be a ‘China threat’ in the Pacific Islands re-gion. Sound and careful assessments of China’s present or likely future intentions are essential in this regard. Books such as Jian Yang’s The Pacific Islands in China’s Grand Strategy: Small States, Big Games, reviewed in this issue, are invaluable in this regard.

Essential requirementMaintaining our credibility in both Washington and Beijing will require both skill and subtlety. Without such credibility, New Zealand will not only have difficulty pursuing its national inter-ests bilaterally with the competing major powers but also not be able to be heard, and have any influence, on the greatest issue of our time: whether these two competing powers will succeed in managing their competition peacefully. Terence O’Brien has spo-ken of the need for New Zealand to be prepared to ‘speak truth to power’ and make the case for a world order that can accommodate both competing powers. Hugh White of the Australian National University argues persuasively that the United States needs to be persuaded to ‘share power’ with China in the Asia–Pacific region. For its part, China shows signs of believing that the United States is in a state of irreversible decline — a view vigorously rebutted in Beijing early in September by Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

The respected former premier of China, Zhu Rongji, once re-

Chris Elder Robert Ayson

marked to the writer that in his view New Zealand had two great advantages in this world: an Asia–Pacific location and the heritage of a great civilisation. To take full advantage of the new opportuni-ties offered by the changed world order, and avoid potentially cat-astrophic pitfalls, will require all the skills and assets we can utilise.

NOTES1. South China Morning Post, 26 Jun 2006.2. The Interpreter, 28 Jul 2012.3. Dominion Post, 26 Jun 2012, and NZ International Review,

vol 37, no 4 (2012).4. See Frank Ching, South China Morning Post, 26 Jun 2006.5. Robert Ayson and David Capie, Asia Pacific Bulletin, no 172,

17 Jul 2012.6. CSS Discussion Paper No 11, 2012.

JOIN A BRANCH OF THE NZ INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

NZIR

Auckland: Treasurer,Auckland Branch NZIIA, Dept of Politics, University of Auckland, Private Bag Auckland 1142. Rates: $50 (ordinary), $40 (student) Christchurch: Treasurer, Christchurch Branch NZIIA, Margaret Sweet, 29B Hamilton Avenue, Fendalton, Christchurch 8041. Rates: $50 (individuals and family), $30 (student)

Hamilton: Treasurer, Hamilton Branch NZIIA, c/- Politics Department, University ofWaikato, Private Bag 3105, Hamilton. 3240. Rates: $40 (ordinary), $30 (student/retired)

Hawke’s Bay: Ken Aldred, I18 North Shore Rd, RD2, Napier 4182. Rates: $40 (ordinary)

Nelson: Hugo Judd, 48 Westlake Rd, RD1, Richmond, Nelson 7081. Rates $50 (individual/couple), $20 (student)

Palmerston North: (ordinary), $35 (student) Timaru: Contact, Rosemary Carruthers, PO Box 628, Timaru 7940. Email [email protected] Rates: $40 (single), $45 (family)

Wairarapa: Secretary, John Schnellenberg, 32 Pownall St, Masterton 5810. Email: [email protected]. Rates: $45 (single), $55 (couples) Wellington: 6140. Rates: $59 (individual and family), $48 (retired, individual and family), $20 (student)

NovDec issue 2012.indd 4 10/10/12 2:27 PM

New Zealand International Review5

Relations between New Zealand and China are very good. We have extremely good trade links, which each year go from strength to strength. Our people are regular visitors to each other’s coun-tries. New Zealand is home to many people who have come here from China. In recent years, New Zealand has had three Chinese members of Parliament — two of them from my own party, the National Party. And our governments meet often and work to-gether effectively.

In 2012, Vice Premier Li described the relationship between our two governments as ‘at its best ever’. It has certainly come a very long way since 1949. That was in the early throes of the Cold War. And New Zealand and China soon found themselves on opposite sides in the conflict in Korea. But in 1972, Richard Nixon made his ground-breaking visit to China. That, on top of the outstanding diplomacy conducted by Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai, provided the opportunity for 28 countries, includ-ing New Zealand and Australia, to officially recognise the Beijing government.

New Zealand recognised China in December 1972, estab-lishing the basis for New Zealand’s enduring ‘one China’ policy. Yet even during those early years, from 1949 to 1972, when the country was largely closed to foreigners, a handful of New Zea-landers left their mark on China. The most famous was, of course, Rewi Alley. Alley was a Cantabrian who went to China in 1927 and spent the rest of his life there — a total of 60 years. While working in Shanghai factories and travelling into the interior of the country, he became aware of the plight of ordinary Chinese peasants and workers. During the war against Japan, he helped establish thousands of small co-operative factories. He founded schools. And he was a prolific author and international publicist for the communist government, while continuing to hold a New Zealand passport.

The photographer Brian Brake also visited China, in the late 1950s. His photographs, taken during the period of the Great Leap Forward, form a unique record of a turbulent period. The New Zealand government is supporting Te Papa to tour a collec-tion of Brake photographs from this era, in partnership with the

A strengthening China–New Zealand link

National Museum of China. They will be on display in Beijing at the time of the 40th anniversary.

Relaxed bansThis level of personal engagement by New Zealanders in China was possible in part because the New Zealand government relaxed travel bans against China before many other Western countries. It also relaxed trade bans. In 1956, New Zealand lifted trade em-bargos imposed on China during the Korean War. Wool, tallow, hides and skins were New Zealand’s main exports in those days, but trade flows remained relatively small. Exporters found it dif-ficult linking buyers and sellers across very different economic systems, and connections were limited. In 1972, bilateral trade between New Zealand and China totalled only $1.7 million, and there were no air links between our two countries.

To a New Zealander in 1972, China would have seemed an unknown, mysterious country of close to a billion people. And it is hard to believe New Zealand figured highly in the minds of most Chinese. So much has changed, then, in 40 years. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations, New Zealand and China have developed a broad and substantial relationship that is among New Zealand’s most important. We have different cultures, dif-ferent histories and different political traditions. So we often have a different perspective on things. However, we are able to express our views with openness, honesty and respect.

That is an important indicator of our positive intent over 40 years. Our trade relationship, in particular, has been a huge success, and momentum has grown very quickly in recent years. In part, that is because of China’s ever-increasing importance in the global economy. In 1981, when several pioneering New Zea-

Henry Kissinger Zhou Enlai

The New Zealand–China relationship has come a long way since it was inaugurated in 1972, and is now so warm that Vice Premier Li has described it as ‘at its best ever’. New Zealand and Chi-na have developed broad and substantial ties that are among New Zealand’s most important. Our trade relationship, in particular, has been a huge success, and momentum has grown very quickly in recent years. People-to-people links between New Zealand and China are also strong. New Zealand has also, from time to time, hosted Chinese naval vessels, and works with China in various regional organisations. Looking forward, it is safe to assume that current trends will continue.

NovDec issue 2012.indd 5 9/10/12 12:39 PM

New Zealand International Review6

land businesses formed the New Zealand China Trade Association, Chi-na accounted for 2.3 per cent of global GDP. By 2011 this had risen to 14.4 per cent. Rapidly rising living standards, increasing urbanisation and a shift to higher-pro-tein diets have supported demand for New Zea-land products.

Hard workBut our booming com-merce is also due to the fact that New Zealand

People-to-people links between New Zealand and China are also strong. Chinese tourism to New Zealand only commenced in earnest at the end of the 1990s but is increasingly significant. Last year Chinese tourist numbers grew by 33 per cent. That number will continue to grow under a new air services agreement that was made earlier this year.

A lot of young Chinese people also come to New Zealand to study. Since the 1990s, China has been New Zealand’s largest education market. New Zealand is today providing a quality ed-ucational experience and pastoral care to around 23,000 Chinese students, and we are aiming to grow that further.

And many Chinese want to stay permanently in New Zea-land, rather than just visiting. China is the second largest source of migrants to New Zealand, behind the United Kingdom. The next census is likely to show a resident population of Chinese in New Zealand of close to 200,000 people. But in relative terms, a greater proportion of New Zealanders actually live in China, rather than vice versa. More than 3000 New Zealanders are living in China, which is not insignificant compared to our total popu-lation of only 4.4 million.

Ship visitsBut the relationship between New Zealand and China is not just about people-to-people and trade relations. From time to time, New Zealand hosts military ship visits from China. We work to-gether in regional organisations such as APEC, and on disaster relief. China was one of several countries to send urban search and rescue teams to assist New Zealand in the immediate aftermath of the Christchurch earthquake, and to donate money for recon-struction. We are very grateful for that assistance.

New Zealand has also aided China after natural disasters, in-cluding the great Sichuan earthquake in 2008. And at the recent Pacific Islands Leaders’ Forum, we announced a new partnership between the Cook Islands, China and New Zealand that will de-liver an improved water mains system in Rarotonga.

This new piece of infrastructure will ensure communities and businesses have access to clean drinking water. It will mean a bet-ter quality of life for the people of the Cook Islands and it will help promote economic growth. The project is the first time New Zealand has worked with China to deliver a major development initiative in the Pacific. It is an example of how we can work to-gether to get the most benefit from our aid programmes in the Pacific.

Brian Brake

and China have worked hard to develop our trade relationship over a number of years. New Zealand was the first country to recognise that China had established a market economy, in 2004. We were the first country to agree bilaterally to China becoming a member of the World Trade Organisation. And in 2008, our two countries signed an historic free trade agreement. Since then, trade between us has grown exponentially.

New Zealand’s goods exports to China have trebled in only four years, and China is now our second-largest export market. Dairy and wood products are the largest export commodities, fol-lowed by meat and wool. New Zealand now exports more than ten times the value of product to China every day than we did in the whole of 1972.

Chinese demand has done much to support the New Zealand economy over the last few years. China is also Australia’s largest export destination, chiefly in mineral resources, providing further indirect benefits for New Zealand, given that Australia is our top trading partner. China is also New Zealand’s biggest source of im-ported goods.

Two-way trade in 2011 totalled $13.3 billion and is rising all the time. Our countries are certainly on track to achieve the goal Premier Wen and I set in 2010, of doubling our trade to $20 billion per annum by 2015.

Our investment relationship with China is much smaller than our trade relationship, but that, too, is growing. China is New Zealand’s eleventh largest investor with $1.8 billion of investment

Chinese visitors to New Zealandin 2011. In particular, Chinese firms have made invest-ments in New Zealand forestry, manufacturing and agri-culture.

Safe havenChina is also investing in New Zealand government bonds, contributing to the record low borrowing rates New Zea-land currently enjoys. New Zealand is seen as a relatively safe haven in these difficult times and Chinese authorities have wanted to diversify their international bond holdings. Recently, there have been some encouraging examples of New Zealand firms investing in China. Fonterra, for ex-ample, has significant plans to increase the number of farms it operates in China, with a roughly NZ$50 million investment per farm. And high-tech firm Rakon opened a US$35 million factory in Chengdu last year.

NovDec issue 2012.indd 6 9/10/12 12:39 PM

New Zealand International Review7

Continuing trendsLooking forward, it is safe to assume that current trends will con-tinue. The centre of gravity of global economic activity will keep shifting from the Atlantic to the Asia–Pacific region. Europe will remain a vital outlet for some of our highest value exports, but our biggest growing markets will be around the Pacific basin. In that environment, New Zealand has a lot to offer.

We are a reliable, competitive and high-quality source of food. We have technical knowledge and expertise that can help coun-tries in this region develop, build infrastructure and add value to their natural resources. We can deliver a world-class education to the next generation of leaders across Asia and the Pacific. And we are a great place to visit, see wonderful scenery and play a few rounds of golf.

We have lots of things we can sell to other countries, but we also want to see New Zealand businesses forming productive part-nerships with Asian and Pacific businesses across the region. There are many new fields of opportunity for New Zealand businesses and people to explore. To operate successfully in this region over coming decades they will need to have a good understanding of China, and of Asia in general.

In February I launched the NZ Inc China Strategy. The strat-egy is about getting greater efficiency and effectiveness across all government agencies that work in, and with, China. And it is about developing more targeted and cohesive services to help successful businesses develop and grow in China. We want to be transparent about our bilateral interests, and get on with advanc-ing them.

The China Strategy has a strong trade and economic focus. And it has been developed with industry groups, businesses and organisations involved in building New Zealand’s relationship

John Key with Rakon CEO Brent Robinson in Rakon’s Class 1000 clean room on 10 September 2010

The Fonterra Building in Auckland

with China. The strategy sets out ambitious, high-level goals, to-gether with actions to achieve them. The five goals are:

to retain and build a strong, resilient political relationship to double two-way trade to $20 billion by 2015, as I men-

tioned above to grow services trade including education services by 20 per

cent, and grow the value of tourism exports by 60 per cent, all by 2015

to increase investment to reflect our growing commercial re-lationship

and to grow high-quality science and technology collabora-tions with China that generate commercial collaborations.

Important document I am pleased the strategy has been positively received in New Zea-land and in China. It is an important document. Our relationship with China is critical to achieving the government’s aim of build-ing a competitive and more productive economy.

One of the immediate outcomes of the strategy was the for-mation of the New Zealand China Council. The council brings together New Zealanders who are engaged in China from across a whole range of fields, including people in the business, academ-ic, science, cultural and education communities. As the council’s chair, Sir Don McKinnon, put it, the council will operate as an umbrella organisation stretching across the breadth of New Zea-land’s relationship with China, and not leaving anyone in the shade.

This is a significant further step in building on what is already a very strong relationship in many areas. The China Strategy also reinforces the government’s commitment to ministerial engage-ment, both as hosts and visitors to China, to build important re-lationships with China’s leadership.

As prime minister, I made my first official visit to China in 2009, where I met President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. And I am hoping to visit China again later this year, to meet the new Chinese leadership. I also hope to launch the New Zealand China Council’s inaugural Partnership Forum in Beijing.

In my view that would be a fitting way to mark the 40th an-niversary of a significant relationship, which has a proud history and can look forward to an even better future. I am confident that we will continue to see New Zealand’s relationship with China go from strength to strength over the coming years.

NovDec issue 2012.indd 7 9/10/12 12:39 PM

New Zealand International Review8

Gradual moves to build New Zealand–Democratic People’s Re-public of Korea (North Korea) relations during the 1970s provid-ed the foundations for later diplomatic relations. With increased interaction between the two countries this year, a review of New Zealand’s position and factors shaping the relationship is time-ly. The New Zealand government’s perspective is mainly derived from archival material held by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, New Zealand Immigration Service and Security Intelli-gence Service. The activities of the New Zealand–DPRK Society, which promotes relations between the two countries, are also out-lined using material from the society’s archives.1

The 1970s witnessed the promotion of bilateral relations, gen-erally unsuccessfully, by North Korea and some New Zealanders. The North Korean ambassador in China met Associate Minister of Foreign Affairs Joe Walding during his March and October 1973 Chinese visits, though the government was not ‘particularly anxious’ for a proposed North Korean visit to New Zealand to occur.

It was within this context that the decision was made in De-cember 1973 to form a society to ‘further good relations’ between New Zealand and North Korea, inform the public, sponsor visits and ‘try and influence the Government to establish official rela-tions’. With a provisional committee formed, the New Zealand–DPRK Society was established in March 1974. Leading society members included senior academics Wolfgang Rosenberg and William Willmott, along with the Reverend Don Borrie. Borrie’s regular contact with the North had started in 1971, and Rosen-berg visited in the following year. Rosenberg wrote that his impres-sion was ‘of an overwhelming economic success’. Indeed North Korea was ‘one of the most potent sources of optimism for the possibility of a world free from hunger’. With the society hoping to establish branches throughout New Zealand, a Christchurch branch was formed in March 1974, amidst what it claimed was ‘somewhat distorted’ media coverage of this development. A Wel-lington branch followed in September. Influenced by a desire to avoid left-wing ideological splits based on Chinese or Soviet inter-pretations of socialism, the society gave priority to forming a small national network over securing mass membership.

A cautious start

New Zealand–North Korean relations were challenging during the 1970s but provided founda-tions for later diplomatic relations established in 2001. Against the Cold War’s background, New Zealand’s position was primarily shaped by the view that the authoritarian regime’s foreign pol-icy was aggressive and unsophisticated, the priority given to relations with South Korea, and the stance of friends and allies. The New Zealand–DPRK Society played a key role promoting rela-tions between both countries during this period. Bilateral relations continue to be challenging and caution remains important in interacting with the North. However, the need for dialogue fostering mutual trust, transparency, and co-operation is even more important today.

After Pyongyang asked the provisional committee if a delega-tion could be received, Walding said in May 1974 that a private, society-sponsored delegation entering on special travel documents was possible. Four North Koreans duly arrived in Christchurch during July to promote relations with a cultural exhibition. The society and Chinese diplomats met them. Their three-week stay included a visit to Wellington. At the exhibition’s opening, Will-mott said that it marked ‘the very beginning of what we hope will be increasing exchange between us’. He expressed his delight that the visit had occurred so soon after the society’s establishment. The delegation felt their visit went ‘very well’, and Rosenberg called it a ‘great success’. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the exhibition ‘very harmless’, the New Zealanders ‘doing all the answering of questions from the few members of the wide-eyed public who strolled in’.

Low-key visit The low-key visit was in line with New Zealand’s cautious ap-proach. Prime Minister Norman Kirk indicated that relations would be opened in due course. New Zealand was gradually moving towards recognising the North at its own pace, and de-veloping contacts with all Asian countries. The Foreign Ministry felt that the visit ‘would be a minor but useful step forward in this process’. Some positive Korean peninsula developments augured well for the future. With Australia establishing diplomatic rela-tions with the North in 1974, there was a feeling that Pyongyang was ‘emerging from its long isolation’.

Don Borrie’s visit to North Korea in 1971

NovDec issue 2012.indd 8 11/10/12 12:36 PM

New Zealand International Review9

Despite the visit New Zealand remained cautious in its ap-proach. In early 1975 the high commission in Canberra was advised not to ‘actively discourage’ approaches from the North Koreans, but to ‘avoid giving any impression that they might lead to an early relaxation of the Government’s position’. This was be-cause the government intended to ‘hold the North Koreans at arm’s length for some time yet’. During May 1975 the North’s ambassador in Indonesia commented that communist victories in Cambodia and Vietnam meant that the ‘tide’ in Asia was ‘running strongly in the right direction’. Thus, it was ‘high time’ for diplo-matic relations after almost a year’s talks. New Zealand’s embassy in Jakarta responded that it would await the ‘natural course of events’.

A North Korean delegation including student and union rep-resentatives was denied visas in April 1976. Rosenberg informed Pyongyang of this, lamenting that the government was ‘unfor-tunately one of the most backward that has ever been elected’. He told the North Koreans that the government’s decision had received much publicity with media, unions and student organ-isations pressing for its reversal. The society contacted Rewi Al-ley seeking his help in promoting New Zealand–North Korean relations. In May 1976 Rosenberg visited North Korea. ‘It’s an incredibly successful country’, he stated afterwards, declaring that he ‘would prefer not to go to the South after such a good recep-tion by the North’. The following month Borrie and trade union-ist Gordon Walker also visited the North, which announced the establishment of a North Korea–New Zealand Friendship Asso-ciation. This was to ‘acquaint the New Zealanders with the Kore-an question’, so that they understood that Korea ‘must no longer be kept divided’. North Korea also proposed a table tennis team’s visit, a proposal viewed by New Zealand officials as ‘a step in its campaign to hasten recognition’. Likewise, the society sought to organise a table tennis team to visit North Korea.

Cultural delegationGiven the precedent of the 1974 delegation’s low-profile visit, the society hoped that another unofficial visit by a cultural delega-tion would be possible. But an initial attempt to obtain visiting visas failed because the North Koreans used official passports. It was not until August 1978 that a delegation finally arrived. The North Koreans held talks with the New Zealand society that they felt provided an ‘important opportunity to further extend and develop’ relations. They also met with trade unionists and uni-versity academics. With its reported political activities violating government guidelines, the visit was controversial. According to Borrie, the North Koreans followed restrictions placed on them making public statements. Early delegations were friendly and did not wish to ‘rock the

boat’. Hence they were consistently ready to adapt to New Zealand government conditions which denied them the right of freedom of speech and public association, restrictions the media did not understand.

Borrie also observed that it was ‘a challenge for the North Koreans to understand the role played by the Society as a voluntary asso-ciation, it not having the linkages to a State system as practiced by the DPRK’.

During late 1979 a society delegation visiting the North was received by North Korea’s deputy prime minister. In an article published after the visit, the delegation observed that the coun-try’s industrial development was ‘remarkable’, and the degree of equality ‘most impressive’. North Korea was ‘very delighted’ with such coverage.

Member of Parliament Warren Freer after visiting North Korea said there were ‘encouraging’ prospects of trade with the North, and remarked that economic conditions were much better than he had expected. The society also contacted US President Jimmy Carter to ask that the United States sign a peace agreement with North Korea, and withdraw its forces from the peninsula. As the decade ended other groups apparently had been in contact with North Korea too.

Regular applicationsBy 1980 the North was applying almost annually to send dele-gations and non-official groups. In March 1980 the government refused visas for associa-tion members invited by the society, and Minister of Foreign Affairs Brian Talboys refused to meet the society. However, 40 North Koreans were re-corded as visiting New Zealand in 1980, pri-marily for business and holiday/vacation. Borrie met a North Korean del-egation that visited Aus-tralia in April that year. These North Koreans in-dicated they would like to invite MPs Bill Rowling and David Lange to the North, given the Labour Party’s ‘relatively positive

Above and below: Reverend Don Borrie in Pyongyang

NovDec issue 2012.indd 9 9/10/12 12:40 PM

New Zealand International Review10

stand’ on their country. They looked forward to a New Zea-land trade union group visiting and a society branch in Dunedin being established, and asked for the names of ‘progressive’ mem-bers of Parliament and universi-ty staff. They also sought infor-mation on New Zealand’s wool industry and to obtain vegetable seeds.

Similarly, New Zealanders visited North Korea. According to North Korean sources, Freer visited again during July 1980. Rosenberg visited the North for the Sixth Congress of the Korean Worker’s Party in October 1980. After this visit he said that Pres-ident Kim Il Sung’s position in North Korea, and the ‘respectful reverence’ of him, was not dis-

Entry refused Explaining the refusal to allow three North Koreans entry in early 1976, Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs Sir Keith Holyoake re-ferred to the North’s unwillingness to deal with South Korea and to resume dialogue on peaceful reunification as major causes of peninsula tensions. With such a visit potentially seen as political, and apparently part of the North’s ‘world-wide political effort’ to achieve wider recognition, the government saw ‘no specific advan-tages’ in allowing the visit. Furthermore, North Korea had ‘one of the most authoritarian regimes in the world’, the repression of freedom of speech and worship exceeding that of governments anywhere else in the region. This reference to lack of freedom in-fluencing New Zealand’s position was questioned in the media, given New Zealand’s relationship with South Korea, with its then lack of democracy. According to Holyoake, New Zealand’s atti-tude towards North Korea ‘ultimately depends on that country’s own actions’. If the North ‘demonstrates that it is disposed to play its part as a responsible member of the international community, New Zealand will be happy to establish diplomatic relations’.

North Korea’s diplomacy with New Zealand was viewed by officials as unsophisticated and aggressive. This reinforced nega-tive perceptions and caused frustration. In June 1974 the embassy in Jakarta complained that the North Korean ambassador, who had been ‘very persistent’ in seeking a ‘courtesy call’, did not take the ‘broadest of hints’ that a meeting was not possible. The follow-ing month the ambassador was described as a ‘first-class creep’. In February 1975 the secretary of foreign affairs expressed frustration that North Korea did not understand that New Zealand was ‘not prepared to be bludgeoned into early recognition [of the North]’. Apparently this ‘message’ had ‘not yet got across’ or ‘more likely, we suppose, it is being ignored or misread deliberately’. Later that year the Jakarta embassy compared discussions with the North Korean ambassador to mounting ‘the old treadmill’ where both parties ‘pedalled hard without result’.

Negative perceptions were further encouraged in the late 1970s. In July 1976 New Zealand’s Bangkok embassy was ad-vised of the ‘likely fruitlessness’ of accepting North Korean calls. Moreover, the 1978 North Korean delegation’s reported political

similar to that of the Queen in New Zealand. Furthermore, the North Koreans had ‘shown the world how under-development and poverty can be overcome within one generation’. In New Zealand the society aimed to ‘prod’ the Labour Party and trade unions into making statements on North Korea, while noting that the ‘seduction of tours to North Korea should be held out’.

Tense relationsNew Zealand–North Korea relations were tense after the Korean War and during the Cold War. Some New Zealanders opposed New Zealand’s involvement in the Korean War, and expressed some support for North Korea. They included MP Reverend Clyde Carr and the New Zealand Communist Party. However, New Zealand’s reluctance to build relations with North Korea de-rived primarily from its opposition to the North’s foreign policy. This was particularly because of its peninsula commitments.

During the 1960s concern was expressed over North Korean aggression, such as its raids into the South. In November 1967 Charles Craw, New Zealand’s United Nations’ delegate, asked whether North Korean violations of the armistice were ‘their re-action to the remarkable progress being made in the Republic of Korea [South Korea] or are they the prelude to aggression on a larger scale’. In 1967 and 1968 the North’s attacks across the de-militarised zone were mentioned in Parliament too.

Attacks in the early 1970s caused further concern. The North failed to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee during August 1974 but killed his wife. The in-cident, which occurred after the North Korean delegation ar-rived in New Zealand, induced Kirk to express New Zealand’s ‘deep regret and sympathy’. Prime Minister Rowling in 1975 recognised that the peninsula was a ‘focal point of great-power interest in the region’, and that a ‘state of tension’ existed. There could, in his view, be ‘no real reconciliation’ until North Ko-rea and its closest friends formally acknowledged and accepted the South’s independent existence. During the same year New Zealand’s Jakarta embassy notified Wellington that the North Korean ambassador had said ‘We have no fear of the South Koreans (wide show of Grandma’s big teeth)’.

The June 2012 senior DPRK delegation in New Zealand with friendship society liaison person Karim Dickie

NovDec issue 2012.indd 10 9/10/12 12:42 PM

New Zealand International Review11

activities in New Zealand, and the South’s accusation that the vis-itors had disguised their status to enter New Zealand, encour-aged the government to refuse visas in March 1980. In November 1981 the ministry noted that the North had conducted a ‘strong diplomatic campaign’ since the late 1960s to gain wider interna-tional recognition and greater support in its competition with the South. However, its diplomacy ‘frequently has been unsophisti-cated, heavy-handed and counter-productive’. This was noted in other countries too. A US official that year said the North Kore-ans were ‘their own worst enemies and usually manage to shoot themselves in the foot pretty quickly’.

UN pressureThe North’s moves to change New Zealand’s policy on Korea at the United Nations caused more criticism. In October 1975, the North’s ambassador in Jakarta requested that New Zealand be ‘ab-sent’ at UN resolutions on Korea. When New Zealand’s embassy identified ‘hurdles’, the ambassador merely ‘cleared them nimbly or (more usually) booted them out of the way’. Later that month another request to ‘abstain’ or be ‘absent’ at UN resolutions on Korea had ‘unpleasant undertones’. North Korea told the Jakarta embassy that ‘since the former reactionary government which sent New Zealand forces into Korea had been toppled by the Labour Party we had hoped you would be more understanding of the aspirations of the Korean people’.

Nor was government sympathy likely to be generated by some moves by Pyongyang and supporters in New Zealand. Delega-tions were expected to cover international travel costs by selling cultural and art items. Borrie found delegations ‘very friendly and cooperative’. However, the items shown reflected the North’s ide-ology rather than being consumer-driven, leading to poor sales. Delegation press conferences were called ‘very doctrinarian’ and ‘very long’ in the media.

Similarly, North Korean printed material received by New Zealand’s embassy in Seoul was deemed not very interesting or useful. Indeed, the society told the North not only that ‘too much material’ was sent abroad but also that it was ‘not appropriate to the New Zealand public’. This was because New Zealanders reacted negatively to the focus on Kim Il Sung as they believed such material reflected a ‘personality cult’. Both the North and the New Zealand society criticised the New Zealand government and the South. The Communist Party was also critical of the gov-ernment’s position. It condemned New Zealand’s refusal to allow delegation visits while having exchanges with the ‘pro-US fascist regime in South Korea’.

Major factorThe South Korean position was a major factor shaping policy. There were some negative perceptions of South Korea in New Zealand, and serious misgivings were expressed over its periods of authoritarianism and political upheaval. Even so, relations grew closer from the early 1960s. In indicating that a gradual opening of New Zealand–North Korean ties was sought, Norman Kirk noted that the decision to establish diplomatic relations would be influenced by consultation with other interested countries, in-cluding South Korea. The ministry felt that an ‘adverse reaction’ from the South was possible over the 1974 visit. However, Seoul was ‘well aware’ of moves towards establishing relations ‘at a suita-ble time and not at the expense of our long-standing relationship with the South’. Prime Minister Robert Muldoon also gave prior-

ity to maintaining close relations with the South. Finally, New Zealand policy was influenced by its friends

and allies such as the United States and Australia. Here Austral-ia’s experiences were especially relevant. The South, along with the United States and Japan, had been unhappy with Australia establishing diplomatic relations with the North. However, the North in October 1975 abruptly withdrew its diplomats (after a North Korean had crashed an embassy car outside the South Ko-rean ambassador’s residence and fled) and issued a note labelled insulting by the Australian government. South Korea had been ‘grateful’ for New Zealand’s decision not to follow Australia when it opened negotiations with the North. Moreover, New Zealand was conscious of illegal activities by North Korean diplomats. For instance, in 1976 the North’s diplomats were forced to leave three Scandinavian countries and Finland after revelations of illegal to-bacco, alcohol and drug dealings. It was also reported in New Zealand that North Korea could not pay its debts to other coun-tries, and might be bankrupt.

Challenging yearsThe early years of New Zealand–North Korean relations, as with later relations, were challenging. Against the Cold War’s back-ground, the New Zealand position was primarily shaped by the view that the Pyongyang regime’s foreign policy was aggressive and unsophisticated, the priority given to relations with South Korea, and the stance of friends and allies. Despite this, the 1970s moves built ties that provided the foundations for the establishment of diplomatic relations in 2001. The New Zealand friendship society played a significant role in promoting relations, and continues to do so. Although New Zealand’s position on North Korean offi-cials visiting is now more relaxed, challenges to strengthening re-lations reminiscent of those influential in the 1970s remain. Here concerns over North Korea’s foreign policy and very poor human rights record that are shared with friends and allies, along with the continuing importance of New Zealand–South Korean relations, are influential. Current relations are further complicated by the North’s nuclear weapons programme and its leadership transition during a period of severe economic challenges.

The North under Kim Jong Un has yet to show strong indica-tions of fundamental change in foreign policy that would facilitate stronger bilateral relations, and caution remains important. How-ever, there have been some positive developments with an apparent desire by the North, assisted by the society, actively to seek closer relations. For instance, in June 2012 a visiting senior North Kore-an delegation indicated that it sought a better relationship, espe-cially in education, cultural and economic fields. The delegation was especially interested in New Zealand’s agricultural technology. New Zealand’s ambassador in Seoul, who is cross-accredited to the North, also presented his credentials in Pyongyang in September. Overall, constructive communication and interaction with North Korea was important in the 1970s in helping to build the foun-dations for a diplomatic relationship. The need for dialogue fos-tering mutual trust, transparency, and co-operation is even more important today with a nuclear-capable country operating within an increasingly inter-connected global community.

NOTE1. See also Paul Bellamy, ‘A reluctant friend — New Zealand’s

relationship with North Korea 1973–1989’, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, vol 14, no 1 (2012).

NovDec issue 2012.indd 11 9/10/12 12:43 PM

New Zealand International Review12

Let me begin with a small reflective tribute to the late Sir Frank Holmes, an absolute stalwart of the Pacific Economic Coopera-tion Council. This must be the first formal or informal PECC meeting I have attended in the last 30 years without Sir Frank being an integral part of the discussion.

Sir Frank, who passed away only recently, was a considerable intellectual influence on me and no doubt many people of my generation interested in international trade. He wrote some of the first applied economics papers I read, often in conjunction with Professor Peter Lloyd for the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research.

Like other international economists of the time — I am thinking of Richard Lipsey, Max Corden and others — Holmes and Lloyd took the theory of the second-best, out of sophisti-cated game theory literature, and applied it in their case to New Zealand’s circumstances of the 1960s and 1970s. Put simply, this thinking hugely influenced the design and policy rationale of New Zealand’s first ever genuine free trade agreement — the CER agreement.

That first comprehensive free trade agreement, finally ratified in 1983, had in turn a huge impact on policy thinking on free trade agreements around the world. It was literally the ‘gold standard’ of free trade agreements of its day. To say ‘of its day’ is probably un-

Stoking the engine of growth

nership proposal and New Zealand’s export future.

Hon Tim Groser is the minister of trade. This article is the edited text of an

-

-

nouncing in June on behalf of New Zealand, Australia, the Unit-ed States and all existing TPP members that I had signed a formal letter inviting the government of Mexico to join the TPP. I also sent a similar letter to the Canadian trade minister.

The TPP is deeply influenced by the same political economy thinking underwriting CER. In other words, public policy ideas advanced decades ago by the two intellectuals Frank Holmes and Peter Lloyd continue to influence real world events such as this. It is a remarkable testimony to Keynes’s point about the persistent tendency of so-called ‘practical men’ to under-estimate the power of ideas.

Before elaborating on the TPP and the significance of Mexico’s and Canada’s entry into the negotiation, I want to restate some basic truths about trade liberalisation, the jobs it creates, the pro-ductivity and innovation it leads to and the new markets it opens up.

I started with high-level game theory. Now let me go straight to the coalface to make the same point. In June I visited a very small New Zealand export company in Hamilton that has abso-lutely nothing to do with New Zealand’s core resource strengths in the primary sector. It is called Proform Plastics. It is an au-tomotive parts company that arose out of the ashes of the old import licensing system and is now overwhelmingly export-ori-ented, having successfully got itself into the global supply chain of a couple of major international automotive companies.

Proform employs about 120 local people in design, adminis-tration and manufacturing. It manufactures everything on site, but often using imported materials, and wins contracts on the quality of its product offering, its service and IP package — it

Sir Frank Holmes Professor Peter Lloyd

derstating its influence; fun-damental design principles like progressive liberalisation over many years to deal with sensitivities, comprehensive product coverage, carefully designed review clauses and so forth continue to be valid and to influence Australian and New Zealand negotiat-ing approaches 30 years on.

Because New Zealand is the legal ‘depository’ or ‘ad-ministrator’ of the Trans-Pa-cific Partnership negotiation, I had the privilege of an-

Tim Groser

NovDec issue 2012.indd 12 9/10/12 1:00 PM

New Zealand International Review13

is not just competing on price. As is the case for most successful things New Zealand does from dairy through to tourism, if it is ‘cheap’ you want, do not come to New Zealand. If you want ‘best value’, then come right in.

Proform is constantly innovating its highly specialised product range on a Kaizen, or ‘continuous improvement’, basis — as any company which is involved in exports must. Trade and innova-tion are joined at the hip. Being a niche player, this company is also proud of its ability to customise its products for the specific needs of its customers. It is in that sense typical of the new genera-tion of export companies that I visit and which give me long-term confidence in this country’s future.

Major opportunitiesAustralia is their major market, but their people told me that they see major opportunities in three markets — the Thailand, Chi-na and, intriguingly, Mexico. They told me that without the free trade agreements we have with China and Thailand, it would have been impossible for them to compete in those markets and em-ploy as many people as they do.

Mexico, they said, was a challenge because of an 18 per cent tariff on the components they make. In fact they said that from their company’s point of view, a free trade agreement with Mexico (given automotive assembly there and high tariffs on components) would be more interesting to them than a free trade agreement with the United States. Given the sensitivity of the impending announcement, I was not then in a position to say ‘well, if a free trade agreement with Mexico is what you want, you have come to the right place!’ I could repeat this story with 853 other examples. Why such a precise number? Because the Ministry of Foreign Af-fairs and Trade and New Zealand Trade and Enterprise surveyed 854 New Zealand export companies in late 2009 to assess the impact of free trade agreements on their companies.

Over 75 per cent of our export companies saw positive in-creases (some substantial) in their business profitability from the removal of these barriers in several of our trade agreements. Just remember this simple reality: the managers who run these export companies do not offer jobs to other people because they want to lose money on their investment of time and capital. They employ more people because they see an opportunity to build a larger and hopefully more profitable business. Profitable New Zealand export companies means jobs. And usually, jobs in the export sec-tor are better paid jobs. The more foreign exchange our exporters earn, the less money we have to borrow from overseas. If I may make a political aside here: it is extraordinary that the people who complain the loudest about foreign investment are the same peo-ple who vociferously oppose trade agreements. It is completely inconsistent.

Clear evidenceOther more sophisticated findings from this large survey of 854 exporters include clear evidence that removal of barriers to trade helped these kiwi companies acquire new knowledge and technol-ogy. Most intriguingly, 42 per cent of companies surveyed saw the lower prices of inputs in the New Zealand market as a result of lowering our own barriers was a real benefit to them.

The last point — that increased competition in the New Zealand market helped our exporters — is, of course, complete-ly unremarkable to the 99 per cent of economists who buy the underlying theory set behind international trade, the theory of

‘comparative advantage’. But we all know this is counter-intuitive to the public of most countries that are in favour of exports and believe imports costs jobs.

So let me approach this from a broader perspective on the ba-sis of an outstanding synthesis of international research produced by the OECD called Policy Priorities for International Trade and Jobs. This was the centre-piece for this year’s annual OECD min-isterial meeting in Paris.

Among the numerous findings of this comprehensive study is a range of practical, anecdotal and econometric estimations. For reasons I will not delve into here I am not a great believer in the value of econometric modelling of gains for trade — there is a persistent tendency of such measures to understate the gains from trade. Having said that, it is notable that OECD modelling sug-gests that a 50 per cent reduction in tariffs and non-tariff meas-ures on a most favoured nation basis for G20 countries would increase New Zealand’s real income by over 8 per cent. Very tidy, even if this is an understatement.

Remarkable statisticMore specifically, I would like to draw attention to one remarka-ble statistic: the share of imported components in manufactured exports has gone from an average of 20 per cent globally to 40 per

A retractable truck bed cover made by Proform Plastics of Hamilton

Pascal Lamy (right) with Speaker of Parliament Lockwood Smith during his visit to New Zealand in 2009

NovDec issue 2012.indd 13 9/10/12 1:01 PM

New Zealand International Review14

cent in only twenty years. As Pascal Lamy, the WTO’s director-general, said on a panel that I was also on in Paris, that figure is almost cer-tainly out of date already and the true figure is probably over 50 per cent.

It turns out that protectionism is even dumber than we thought. The implication is that if you want to remain competitive in world manufacturing exports and be part of the global value chain, you must ensure your manufacturers can access world-class inputs at competitive prices. If not, you are going to see your manufacturers fall out of the global value

tries this is associated with far stronger productivity growth. On average, an increase of 10 percentage points — the aim of this government — has histori-cally been associated with an average 4 per cent increase in output per work-ing-age person.

A principal transmission mechanism is productivity. Depending on the coun-try, a 10 percentage increase will lead to an average increase between about 2 and 10 per cent in long-term labour produc-tivity. That is the key to higher wages.

chain. My tiny Hamilton example — Proform Plastics — could never have exported its automotive parts into the global value chain if its imported inputs were still subject to high tariffs and import licensing because an earlier generation of New Zealanders thought we should protect everything in the name of ‘jobs’.

If we want to drill down even deeper we can make the same point with respect to liberalising trade in services. OECD research indicates that a one percentage point higher services import share is associated with a 0.3 per cent higher export share. For high-tech business it is much higher.

The boundaries between being a ‘manufacturer’ or a ‘services’ exporter are increasingly porous. So if you want to help your man-ufacturing exporters, they need access to the most competitive services, which are increasingly deeply enmeshed into their prod-uct offering — think again of my guys in Hamilton or numerous other and far larger New Zealand exporters I could have used to make the point.

Positive linksThis joint piece of work that I am referencing by the OECD, the WTO, UNCTAD, and the ILO is a mine of information about the strong positive links between trade, growth and jobs. It is not just about rich, developed countries. The research suggests, for ex-ample, that in sub-Saharan Africa a one percentage point increase in the ratio of trade to GDP is associated with a short run increase in their growth rate of approximately 0.5 per cent per annum, which grows to nearly 0.8 per cent after ten years.

And it applies to New Zealand. That is why we have set this ambitious goal of increasing the ratio of our exports from 30 to 40 per cent of GDP by 2025. We know that for OECD coun-

Trade also deepens physical and human capital.The mass of evidence in favour of open trade is so strong that

the OECD caustically concludes as follows: Despite all the debate about whether openness [on trade]

contributes to growth, if the issue were truly one warranting nothing but agnosticism, we should expect at east some of the estimates to be negative.... The uniformly positive esti-mates suggest that the relevant terms of the debate by now should be about the size of the positive influence of openness on growth... rather than about whether increased levels of trade relative to GDP have a positive effect on productivity and growth.

Safety netsIncreased openness to trade is not some magic wand, of course. We still need well-designed safety nets, well designed labour mar-kets, education systems that work for people with low skills and often low expectations. Trade policy cannot solve these problems.

However, even here, trade can help. Although the evidence is not as conclusive as it is with respect to growth, the ILO research quoted in the OECD study is quite clear on, for example, the relationship between trade and working conditions. Despite all the allegations around the so-called ‘race to the bottom’, the evi-dence suggests the opposite: open trade has a positive relationship with working conditions in developing countries. As the study concludes: ‘Indeed the positive effect of trade on investment and incomes carries with it important implications for reduced child labour, reduced workplace injuries, and informality, while offer-ing new opportunities for female entrepreneurs’.

For our country, the last 35 years have seen a struggle to have

Leaders of TPP member states and prospective member states on the sidelines of the APEC summit in Yokohama, Japan, 11 November 2010

access to markets, as we have gone through a wrenching adjustment process from an economic mo-no-culture (we were an offshore farm for Britain) to developing these platforms into the emerging economies.

And we are making progress. Nearly 50 per cent of New Zealand exports are now covered by free trade agreements from our earliest with Australia through to the most recent free trade agreement with Hong Kong. Obviously there are a variety of other factors influencing the rate of growth of our exports than just these free trade agreements. Never-

NovDec issue 2012.indd 14 11/10/12 12:39 PM

New Zealand International Review15

theless it is striking that if we just look at the last four years, the cu-mulative growth of New Zealand exports to countries that we do not have a free trade agreement with is a tiny 3 per cent — that is 3 per cent over the four-year period, not 3 per cent per annum.

Worst recessionThis is not entirely surprising — we went through the worst reces-sion in 70 years in 2009 and many of the major developed economies are a bit below or only a bit above the real GDP levels they enjoyed in 2008. But contrast that anaemic growth of our exports to non-free trade agreement countries with the growth of New Zealand exports to

Bill English

countries with which we have free trade agreements. For these countries, our exports in the last four years grew 23 per cent, or nearly eight times as much as exports to our non-free trade agree-ment markets. In the case of China the growth of our exports is simply spectacular — 160 per cent — and the growth of imports from New Zealand is far faster than the growth of imports into China from all sources.

I am as committed to the WTO and the multilateral trading system as any New Zealander — I spent eleven years of my life in Geneva on the GATT and WTO. It remains my firm view that the international community will have to come back to Geneva at some point and find a way forward. It is inconceivable that what was agreed in 1994 at the conclusion of the Uruguay Round — I was our chief negotiator — could forever represent the high wa-termark of political achievement. You cannot have a global supply chain without a vibrant global set of rules and commitments that keep pace with structural change.

Right now I cannot see a way forward, but what a Plan B New Zealand is cooking up through our free trade agreements and the TPP. I will leave aside here a range of other free trade agreements we are trying to move forward, such as Taiwan, India, Russia and Korea, and focus on the TPP.

The TPP has a long period of political gestation. It started life as ‘P2’ — a bilateral free trade agreement between New Zealand and Singapore with precisely this strategic objective, to act in ef-

the TPP — as nine countries. In the near future, this will become eleven, as we move to include Canada and Mexico. Where Japan now goes is suddenly the next frontier issue. And New Zealand, I repeat, is the ‘depository’ of the agreement — because of this negotiation history.

Three changesIt is worth pointing out that this slow evolution encompasses three changes in the election cycle of New Zealand. Our external trading interests do not change with a change in government, and history shows that a core New Zealand advantage is that the two major political parties have successfully quarantined trade policy from the normal democratic arm wrestle. It is a huge strategic advantage.

In this very sophisticated international game, the only thing this tiny country of ours has to sell is smart strategy implemented by a team of deeply experienced New Zealanders, each of whom has extraordinary personal networks to draw on.

The TPP is now the centre-piece of trade strategy of the Unit-ed States. Yes, we are in a process of transition of power to the emerging economies, led by China. But the United States is still the pre-eminent power and is using the TPP to try to develop a 21st century, gold-standard trade agreement that can act as a broader template for trade and investment integration in the Asia–Pacific region.

Reflect for a moment on the phrase ‘integration in the Asia– Pacific’. When we look at the relatively poor export performance of New Zealand over the last 30 years and compare this perfor-mance with other small developed economies (defined as less than 20 million people), what emerges is quite interesting. There are twenty such countries in the OECD, and only three of them are not located in Europe. Because these sixteen countries, all of which perform markedly better than New Zealand in terms of exports to GDP, are close to large, wealthy markets, it is clear that their close regional integration has, at least up to now, been ex-tremely helpful to their export performance.

We cannot shift our geography, just our mentality, our policies and our performance. And our region is the Asia–Pacific. If the TPP is the key instrument to closer regional integration, you can see at least intuitively that this has got to be helpful in the long term.

Finance ministers at the APEC meeting in Honolulu in November 2011 took the opportunity to discuss the TPP

fect as a bridge to a trans-Pacific trade agreement (we envisaged five initial countries). Then, just prior to completion of that free trade agreement and at APEC in Auckland 1999 we hammered out in principle an agreement to negotiate ‘P3’ (Singapore, New Zealand, Chile); Brunei joined and the negotiation of what be-came P4 (or Pacific Four) was completed in 2004 and ratified in 2005.

Since 2010, we have been negotiating the next iteration —

NovDec issue 2012.indd 15 9/10/12 1:02 PM

New Zealand International Review16

1989 Mark Pearson, Paper Tiger, New Zealand’s Part in SEATO1954–1977, 135pp

1991 Sir Alister Mclntosh et al, New Zealand in World Affairs,Volume I, 1945–57, 204pp (reprinted)

1991 Malcolm McKinnon (ed), New Zealand in World Affairs, Volume 11, 1957–72, 261pp

1991 Roberto G. Rabel (ed), Europe without Walls, 176pp1992 Roberto G. Rabel (ed), Latin America in a Changing World

Order, 180pp1995 Steve Hoadley, New Zealand and Australia, Negotiating

Closer Economic Relations, 134pp1998 Seminar Paper, The Universal Declaration of Human

Rights,35pp1999 Gary Hawke (ed), Free Trade in the New Millennium, 86pp1999 Stuart McMillan, Bala Ramswamy, Sir Frank Holmes, APEC

in Focus, 76pp1999 Seminar Paper, Climate Change — Implementing the Kyoto

Protocol1999 Peter Harris and Bryce Harland, China and America —The

Worst of Friends, 48pp1999 Bruce Brown (ed), New Zealand in World Affairs, Volume

3,1972–1990, 336pp2000 Malcolm Templeton, A Wise Adventure, 328pp2000 Stephen Hoadley, New Zealand United States Relations,

Friends No Longer Allies, 225pp2000 Discussion Paper, Defence Policy after East Timor2001 Amb Hisachi Owada speech. The Future of East Asia — The

Role of Japan, 21pp2001 Wgton Branch Study Group, Solomon Islands — Report of a

Study Group2001 Bruce Brown (ed), New ZealandandAustralia— Where are

we Going’. 102pp

for the Next Decade, 78pp2002 Stephen Hoadley, Negotiating Free Trade, The New Zealand–

Singapore CEP Agreement, 107pp2002 Malcolm Templeton, Protecting Antarctica, 68pp

2002 Gerald McGhie and Bruce Brown (cds), New Zealand and the

2004 A.C. Wilson, New Zealand and the Soviet Union 1950–1991, A Brittle Relationship, 248pp

History of Regional and Bilateral Relations, 392pp

Diplomacy and Dispute Management, 197pp

Tribute to Sir George Laking and Frank Corner, 206pp

Foreign Policy Issues, 2005–2010, 200pp2006 Malcolm Templeton, Standing Upright Here, New Zealand

in the Nuclear Age 1945–1990, 400pp2007 W

Status 1907–1945, 208pp

Implications, 92pp2008 Brian Lynch (ed), Border Management in an Uncertain World,

74pp2008 Warwick E. Murray and Roberto Rabel (cds), Latin America

Perspectives, 112pp

World,197pp2010 Brian Lynch (ed), Celebrating 75 Years, 2 vols, 239, 293pp2011 Brian Lynch (ed), Africa, A Continent on the Move, 173pp2011 Brian Lynch and Graeme Hassall (cds), Resilience in the

2012 Brian Lynch (ed), The Arab Spring, Its Origins, Implications and Outlook, l43pp

Issues Facing New Zealand 2012–2017, 218pp

For other publications go to www.vuw.ac.nz/nziia/RecentPublicationshrm

NZIIA PUBLICATIONS

Enormous momentumThe TPP now has enormous momentum. TPP leaders agreed in Honolulu in November — New Zealand was led by Deputy Prime Minister Bill English since it was in the middle of our general elec-tion campaign — on a set of very high benchmarks, including elim-ination of all tariffs. There is no point in pretending that you are creating a ‘21st century, gold-standard trade agreement’ if you do not deal with the detritus of 20th century trade barriers — tariffs. The market has moved on. It would be like trying to sell a 1997 Palm Pilot to a Californian digital native. You will not make the sale.

Make no mistake about it. This is going to challenge a num-ber of the participants, especially on their most sensitive agriculture sectors, but if this is not to end as a farce it is something they are going to have to do. At the same time, since dairy lies at the heart of some of the most politically sensitive issues (the economics are quite another matter), we and Australia have said we can be very, very patient to get to the right place.

Once again, our reference point is the design of CER: slow, pro-gressive liberalisation of the most sensitive areas. Time is not the essential point: it is getting to the right long-term result that actually matters.