No Duty, No Accountability? Not so Fast Mississippi Embraces … · 2013-02-22 · For example,...

Transcript of No Duty, No Accountability? Not so Fast Mississippi Embraces … · 2013-02-22 · For example,...

10 The MDLA Quarterly • Winter 2012

Christina Adcock has been a partner in the Mobile, Alabama, office of Adams and Reese, L.L.P. since 2005 and is licensed in Mississippi and Alabama. Ms. Adcock is a member of the firm’s litigation practice group, handling direct action insurance lawsuits, products liability and professional liability matters.

Great American E&S Insurance Company v. Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer, P.A. addresses unique issues between insured parties, excess insurance companies and attorneys retained by primary insurance companies, as well as the duties owed and remedies available when allegations of legal malpractice and negligence are made.1 At the same time, the case presents a matter of first impression in Mississippi: whether an excess insurer can pursue legal malpractice claims against the insured’s attorney through equitable subrogation.2 After granting certiorari review, a majority of the Mississippi Supreme Court held excess insurers may pursue claims against an insured’s attorney(s) through equitable subrogation while only a plurality of the court concluded the malpractice and direct

negligence claims could not pass Rule 12(b)(6) muster.

This article analyzes the plurality’s reasoning in precluding claims for direct negligence and, given relevant Mississippi law, Mississippi litigants’ possible options for pursuing claims of direct negligence under similar circumstances. It also analyzes the Court’s decision to permit equitable subrogation and discusses certain implications and questions the remedy has on defense practitioners going forward.

The Quintairos Case

Quintairos arises from the Chase Lawsuit,3 where a nursing home allegedly provided negligent and inadequate care to Huldah Chase.4 The defendant nursing home had

two insurance policies in place: a primary policy through Royal Indemnity Company (“Royal”) with limits of $1,000,000 and an excess policy through Great American E&S Insurance Services (“Great American”) with limits of $8,000,000 over-and-above the primary policy’s limits.5

Although not primarily obligated to defend the case, Great American requested reports providing evaluations of the claims from the nursing home’s defense counsel chosen by Royal.6 The reports opined the Chase Lawsuit’s settlement value was between $150,000 and $400,000 and advised counsel would need to designate experts.7 At the time of these reports a physician expert had been contacted but not retained.8

In November 2003, however, Royal reassigned the Chase Lawsuit to Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer, P.A. (“the Quintairos firm”).9 While the Plaintiff timely identified two experts by the December 15, 2003 deadline, the Quintairos firm did not. The Quintairos firm also had no attorneys licensed in the State of Mississippi who could represent the nursing home at trial.10

Nevertheless, the Quintairos firm worked the case, and, in January 2004, provided a report evaluating the Chase Lawsuit at $250,000 in compensatory damages “based on known facts” with a “trial value” of $500,000.11 In February 2004, the Quintairos firm belatedly attempted to identify an expert witness, but the plaintiff successfully had the expert struck.12 Not surprisingly, the Quintairos firm gave its valuation of the settlement value a significant upward push from $500,000 to “between $3,000,000 and $4,000,000.”13 This was Great American’s first notice the Chase Lawsuit may implicate its excess coverage.14

No Duty, No Accountability? Not so Fast......Mississippi Embraces Equitable Subrogation

By Christina M. Adcock and Nicholas F. Morisani

Nicholas Morisani is an associate in the Mobile, Alabama, office of Adams and Reese, L.L.P. A member of the firm’s litigation practice group, Mr. Morisani’s practice focuses on insurance defense and corporate law. Mr. Morisani is a 2009 graduate of Mississippi College School of Law, where he served as president of the MDLA Student Chapter.

1 No. 2009-CT-01063 SCT, 2012 WL 4945958, at *3-5 (Miss. October 18, 2012) (“Quintairos II”).2 Great American E&S Insurance Company v. Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer, P.A., No. 2009-CA-01063 COA, 2012 WL 266858, at *11 (Miss. Ct. App. January 31, 2012) rev’d on other grounds No. 2009-CT-01063 SCT, 2012 WL 4945958 (Miss. Oct. 18, 2012).3 The Estate of Huldah Chase, et al. v. International Healthcare Properties, et al.4 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *1.5 Id. at *1.6 Id. at *1.7 Id. at *1.8 Id. at *1.9 Id. at *1.10 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *2.11 Id. at *1.12 Id. at *2.13 Id. at *2.14 Id. at *2.

The MDLA Quarterly • Winter 2012 11

Great American consequently retained counsel to protect its interests and the interests of the nursing home.15 Royal tendered its policy limits and turned the case over to Great American, which eventually paid an undisclosed sum of money to settle the Chase Lawsuit.16

Great American then sued Royal and the Quintairos firm asserting claims for equitable subrogation, legal malpractice, and several negligence-based claims.17 The Quintairos firm successfully moved to dismiss all claims on the basis there was no attorney client relationship between Great American and the Quintairos firm.18 On appeal, the Mississippi Court of Appeals reversed and held Great American sufficiently alleged the existence of an attorney client relationship as the Quintairos firm’s evaluations and opinions as to settlement value amounted to the provision of legal services to Great American.19 The court of appeals also concluded Great American properly plead claims for negligence and equitable subrogation.20

The Quintairos firm sought certiorari review, and the Mississippi Supreme Court took a different view.21 Namely, a plurality of the court rejected Great American’s direct legal malpractice claim on the basis claims for legal malpractice require proof of an attorney client relationship, and the Quintairos firm’s evaluations and opinions were insufficient to establish such a relationship. The plurality then labeled the negligence-based claims as professional negligence, which also required an attorney client relationship between the Quintairos firm and Great American to survive.22 The plurality further concluded the claim for negligent misrepresentation failed given Great American did not allege facts suggesting the Quintairos firm’s opinions were misrepresented.23 A majority of the supreme court, however, adopted the court

of appeals’ opinion and held Great American could utilize equitable subrogation to pursue the legal malpractice claims.24

Negligence

Looking first to the negligence-based claims, the plurality maintains Great American stated sufficient facts to establish causes of action for legal malpractice and negligence against the Quintairos firm. The plurality nevertheless held the negligence-based claims were barred because Great American’s allegations amounted solely to professional negligence based on the Quintairos firm’s case evaluations, which required an attorney client relationship to stand. The holding implies attorneys can be held accountable for legal, professional services but not for other professional services.

This premise is the subject of Justice Randolph’s dissent discussing non-legal professional services and Mississippi’s foreseeability approach to determining duties owed by those performing professional services. It is axiomatic lawyers provide professional services to their clients; however, lawyers provide a myriad of other services to clients and third parties which may not be considered legal counsel or legal services in the traditional sense. For example, lawyers respond to audit inquiries from accountants regarding litigation, bank inquiries regarding client legal expenses for debt ratio calculations, and workers compensation carriers regarding employee information when formulating annual premiums. In these scenarios, the information supplied by attorneys is designed to aid the third parties in completing tasks on behalf of the clients. Information provided to these third parties must be, above all else, reliable. After reading Quintairos, the first question

seems to be how do excess insurers protect their interests when relying on attorneys who owe them no duty given the lack of an attorney client relationship? Moreover, how do attorneys balance duties to the insured and primary insurer and avoid a subrogation claim from an excess insurer, which would jeopardize privilege?

The plurality opinion does not clearly recognize a distinction among legal services, implying there is little difference between legal malpractice and negligence. The Amended Complaint asserted the Quintairos firm provided settlement evaluations and trial values to the excess insurer, but the plurality found these courtesy copies did not constitute legal services to the excess insurer, which would create an attorney client relationship. Regardless of whether the reports created an attorney client relationship, it is beyond dispute these reports constituted a professional service rendered to Great American as the reports were submitted upon Great American’s request, in compliance with the insured’s obligation to notify and cooperate with Great American, and with the knowledge Great American would use the reports to determine if its coverage layer was implicated. Thus, it appears there is a certain set of professional services not strictly legal in nature and which have an obvious use to and effect on insureds and third parties, but for which there is no recourse to the injured when negligently performed.25

A case closely akin to Quintairos and further demonstrative of the need for a clear, substantive distinction between professional and general negligence is Century 21 Deep South Properties, Ltd. v. Corson.26 There, the court specifically found it unnecessary to establish an attorney client relationship in a legal malpractice action involving title work when reasonably foreseeable entities,

15 Id. at *2.16 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *2.17 Quintairos I, 2012 WL 266858, at *3 rev’d on other grounds No. 2009-CT-01063 SCT, 2012 WL 4945958 (Miss. Oct. 18, 2012). The negligence-based claims were claims for negligence, gross negligence, negligent misrepresentation, and negligent supervision.18 Id. at *4.19 Id. at *5-9.20 Id. at *4, 9-10.21 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *2.22 Id. at *4-5. Although concurring with respect to the equitable subrogation issue, Justice Randolph authored an enlightened, persuasive dissent arguing the negligence-based claims should survive through Mississippi’s use of the “foreseeability approach” to negligence claims involving professional services. Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *7 (Randolph, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).23 Id. at *5. 24 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *2-3. Justice Kitchens dissented as to the equitable subrogation issue asserting a host of reasons why he believed the doctrine should not apply under the circumstances. Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *2 (Kitchens, J., dissenting).25 Contra Strickland v. Rossini, 589 So. 2d 1268, 1277 (Miss. 1991) (quoting Touche Ross v. Commercial Union Ins., 514 So. 2d 315, 319 (Miss. 1987)) (recognizing the restatement position adopted by the court in Touche Ross “permits parties who are foreseeable recipients of a negligently prepared opinion and who detrimentally rely on that opinion in their business affairs to recover from the person offering the opinion.”).26 612 So. 2d 359 (Miss. 1992).

12 The MDLA Quarterly • Winter 2012

for proper business purposes, detrimentally rely on the work and suffer damage. Corson instructs the attorney client relationship is one factor to be considered when analyzing duty. Yet, the plurality dismissed Corson’s applicability asserting the case is limited to title work, but that narrow interpretation raises questions. Title work is not so appreciably different from other forms of information sharing, all of which are presumed reliable. As noted above, audit firms, financial institutions, and insurers are third party entities known to rely on information attorneys provide for clients (and insureds). The question begs: how is an excess insurer any less entitled to competent professional service?

The plurality’s interpretation of “professional negligence” to include any lawyer activity (other than title work), may have the effect of insulating attorneys and law firms from being held accountable when lawyers negligently undertake to assist clients in less traditional ways and arguably places lawyers in that special category courts have sought to avoid. This seemingly can be rectified by recognizing and breathing precedential life into the distinction between professional and general negligence, which would render the existence of an attorney client relationship a requirement in only one of two causes of action when legal malpractice and general negligence are asserted separately.

The existence of such a distinction would comport with the line of cases recognizing negligence claims stemming from the performance of professional services are not restricted by privity.27 These cases posit privity (the attorney client relationship) as only one factor used in determining what duty is owed to a third party. Viewing privity as only a factor to consider rather than an element to be required, the more relevant question thus becomes whether it is reasonably foreseeable for third parties to rely on the product of the professional services.28

Legal Malpractice

No where does the calling for a clear, substantive distinction clamor more than in the presently obscure divide between legal malpractice claims and negligence claims. The totality of the plurality’s decision belies the dicta defining legal malpractice as simply a “negligence action dressed in its Sunday best.”29 The first element necessary to the prosecution of a legal malpractice claim is the existence of an attorney client relationship. This relationship is grounded in expertise, experience, respect and the absolute knowledge that client confidences will be protected. Clients rightly have a heightened expectation of loyalty from their attorneys, and attorneys have a heightened duty to their clients in the performance of services. Quintairos’ separation of legal malpractice from simple negligence solely by superficial means serves to diminish the duties owed to the client and overlook the practicality that lawyers provide a vast array of legal and non-legal, but necessary, professional services on a daily basis.

The plurality opinion places extraordinary weight on Great American’s inability to establish an attorney client relationship with the Quintairos firm and, thus, its lack of standing to bring a legal malpractice claim. The Court indicates the services the Quintairos firm rendered were not sufficient to create such a relationship and, unlike the Corson exception for title work, the insured gains no real benefit from counsel sharing information with excess insurers.30 In an excess situation, however, the attorney for the insured is hired by the primary insurer paying the defense costs and to whom the attorney has a duty with regard to reporting and evaluation governed by the insurance contract with the insured and the insurer’s guidelines. Given there is no direct relationship between the excess insurer and the attorney, complying with the excess policy provisions could create an attorney client relationship and/or constitute an

additional benefit to the insured outside the terms of the primary policy. If the case reports and evaluations contain confidential client information and provide a benefit to the insured, then an excess insurer may be in a better position to establish an attorney client relationship.

Nevertheless, while finding Great American lacked standing to bring the malpractice claim on its own; the Court nonetheless allowed the equitable subrogation of the claim thereby necessarily permitting excess insurers to stand in insureds’ shoes in the attorney client relationship. Thus, despite an excess insurer’s inability to bring them directly, legal malpractice claims will move forward as if at the behest of the insured. An excess insurer will have full access to once-forbidden, privileged information and ultimately be in almost the identical position it would have occupied had the direct claim for legal malpractice been allowed.

Equitable Subrogation

The analysis of the majority’s decision to allow equitable subrogation begins with the court of appeals’ treatment of Judge Carlton’s objection to excess insurers asserting claims against an insured’s attorneys through equitable subrogation. In dissent, Judge Carlton points out the existence of varying views toward permitting excess insurers to use equitable subrogation to assert legal malpractice claims against an insured’s defense counsel.31 One of those views holds excess insurers should not be permitted to assert legal malpractice claims through equitable subrogation because legal malpractice claims are not assignable.32 The majority responded to Judge Carlton’s reliance on Weiss by simply stating “Mississippi law does not prohibit the assignment of legal malpractice claims . . . .”33 The importance of this point should not be mistaken by its subtle nature.

27 Touche Ross, 514 So. 2d at 319.28 Touche Ross involved independent auditor who was found liable to recipients of the audit, who were reasonably foreseeable users, who detrimentally relied on the financial statement in the audit, and the court specifically rejected the notion only known third parties, as opposed to reasonably foreseeable users, could successfully assert negligence claims. This question ostensibly was answered by the Mississippi Supreme Court. See Century 21 Deep South Properties, Ltd., et al. v. Corson, 612 So. 2d 359, 374 (Miss. 1992) (“Reliance on a licensed professional to perform his work competently is imminently reasonable.”).29 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *4.30 Quintairos II, 2012 WL 4945958, at *3-5. In addition, Corson recognized title attorneys are fully cognizant third parties outside the attorney client relationship rely on their opinions, creating a duty to those third parties. 612 So. 2d at 373-74. The Quintairos opinion, however, distinguishes the title situation from seemingly all other legal work.31 Quintairos I, 2012 WL 266858, at *14-15 (Carlton, J., dissenting) rev’d on other grounds No. 2009-CT-01063 SCT, 2012 WL 4945958 (Miss. Oct. 18, 2012) (citing State Farm Fire and Casualty Company v. Weiss, 194 P.3d 1063, 1065 (Colo. Ct. App. 2008)).32 Capitol Indem. Corp. v. Fleming, 58 P.2d 965, 969 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2002); Fireman’s Fun Ins. Co. v. McDonald, Hecht & Solberg, 30 Cal. Rptr. 2d 424, 426-30 (Cal. Ct. App. 1994); Weiss, 194 P. 2d at 1068.33 Quintairos I, 2012 WL 266858, at *11 rev’d on other grounds No. 2009-CT-01063 SCT, 2012 WL 4945958 (Miss. Oct. 18, 2012).

The MDLA Quarterly • Winter 2012 13

The court of appeals’ reference to the assignability of legal malpractice claims seems to serve as foundational support for permitting equitable subrogation. Yet, the court of appeals’ single reference to Mississippi’s permissive assignment of legal malpractice claims touches on one aspect of the complicated relationships between, and rationales for and against assignability of, legal malpractice claims and equitable subrogation.34 Although it works to distinguish the line of cases precluding equitable subrogation based on the non-assignability of legal malpractice claims, reliance on assignability, without more, may prove confusing in future litigation. It does not appear this concept is uniformly accepted in the minority of jurisdictions allowing equitable subrogation, as most of those jurisdictions do not permit blanket assignment of legal malpractice claims.35 Some proffered rationales for allowing equitable subrogation, despite non-assignability, include the alleviation of public policy concerns with subrogation because insurers are simply enforcing duties already owed to insureds and unforeseeable, unrelated strangers cannot capitalize on such claims in the marketplace.36 Yet, by adopting an opinion that holds legal malpractice claims are assignable under Mississippi law to justify subrogation of such claims, the Mississippi Supreme Court may in the future

see litigants assign malpractice claims to unknown or unforeseen third parties without the need to assert claims through equitable subrogation.37

Nonetheless, allowing excess insurers to assert claims for equitable subrogation against insureds’ defense counsel provides excess insurers with a reasonable remedy. Quintairos makes clear allowing excess insurers to assert claims through equitable subrogation creates a mechanism for avoiding the situation where both the insured and primary insurer have no incentive to pursue claims against the insured’s defense counsel simply because the insured was prudent enough to purchase excess insurance.38 Secondly, an excess insurer should not be required to retain defense counsel upon the filing of a complaint which merely alleges damages that come within the ambit of an excess policy. Justice Chandler’s dissent arguing Great American could not utilize equitable subrogation because it was on notice of the amount of damages claimed by the Chase Lawsuit and was negligent in failing to protect its interests by hiring its own counsel does not necessarily follow from prior precedent.39 In addition, if the dissenting view prevailed, excess insurers would be required to treat any claim as if it was the primary insurer for the occurrence. In so holding an insured’s attorneys accountable, Quintairos avoids such waste.

At the end of the day, the implications of Quintairos for defense practitioners are many. First, defense counsel for insureds retained by primary insurers should now consider, in addition to serving both the insured and primary insurer’s interests, taking steps to obtain waivers from excess insurers and/or providing disclaimers. In addition, defense counsel for insureds should consider changing reporting strategies or attempting to shift the communication with excess insurer’s to the insured.40

Counsel for excess insurers face similar obstacles. For example, counsel for excess insurers can assert no greater right in the claims than the insured possesses and must understand the excess insurer simply “stands in the shoes” of the insured.41 The excess insurer is susceptible to the very same defenses that may have been asserted against the insured such that counsel must factor those issues into their strategy.42 The excess insurer additionally is limited to asserting only those claims the insured may have been able to assert against its attorney.43 Under Quintairos, the available recovery for excess insurers, at most, is the amount of money the insurer was required to pay on behalf of the insured in whose shoes the insurer stands, arguably precluding an award of pre-judgment interest or punitive damages thus necessitating a cost-benefits analysis.44 Additionally, permitting equitable

34 Although the authors were unable to locate Mississippi case specifically treating the issue of whether legal malpractice claims are assignable, the parties’ briefs in Baker Donelson Bearman & Caldwell, P.C. v. Muirhead involved legal argument as to whether legal malpractice claims are assignable. 920 So. 2d 440 (Miss. 2006). Speaking through Justice Dickinson, the Mississippi Supreme Court opted not to pass on the parties’ respective arguments as to whether Mississippi law permitted assignment of legal malpractice claims but treated the assignment as valid. Id. at 447. 35 See, e.g., TIG Ins. Co. v. Chicago Ins. Co., 00 C 2737, 2001 WL 99832 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 1, 2001) (applying Illinois law) (finding Illinois courts would allow legal malpractice claims to be asserted through subrogation despite the fact legal malpractice claims are not assignable under Illinois law because subrogation would have fundamentally different results than assignment: “Unlike assignment, subrogation would not lead to the merchandising of malpractice claims. Though a claim can be assigned to anyone willing to pay for it, subrogation rights can be exercised only by those who have fulfilled a duty . . . to pay for another’s loss. . . . [S]ubrogation [would not render] legal malpractice claims . . . a commodity available to the highest bidder.”).36 Nat’l Union Ins. Co. v. Dowd & Dowd, P.C., 2 F. Supp. 2d 1013, 1023-24 (N.D. Ill. 1998).37 Accord St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Birch, Stewart, Kolasch & Birch, LLP., 379 F. Supp. 2d 183, 196 (D. Mass. 2005) order confirmed sub nom. St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Birch, Stewart, Kolasch & Birch, LLP, 408 F. Supp. 2d 59 (D. Mass. 2006) (applying Massachusetts law) (reasoning that because Massachusetts courts permit legal malpractice claims to be assigned in certain circumstances, Massachusetts courts would permit legal malpractice claims to be brought through equitable subrogation).38 Quintairos I, 2012 WL 266858, at *12 rev’d on other grounds No. 2009-CT-01063 SCT, 2012 WL 4945958 (Miss. Oct. 18, 2012).39 While intuitive and certainly reasonable in theory, this contention arguably conflicts with prior Mississippi precedent making clear ordinary negligence is not a per se bar to equitable subrogation. First Nat. Bank of Jackson v. Huff, 441 So. 2d 1317, 1320 (Miss. 1983). The plurality thus rejected the position that Great American’s failure to retain its own counsel upon notice of the Chase Lawsuit bars its use of equitable subrogation.40 As Professor Jeffrey Jackson points out, yet another potential implication for defense counsel may arise in the context of an excess insurer’s attempt to assert legal malpractice claims through equitable subrogation against Moeller counsel whose sole obligation is to the insured and at times may be contrary to the insurer’s interests. See Jeffrey Jackson, Miss. Ins. Law and Prac. §12.14 (2012). 41 Indiana Lumbermen’s Mut. Ins. Co. v. Curtis Mathes Mfg. Co., 456 So. 2d 750, 754 (Miss. 1984) (citing cases).42 St. Paul Prop. & Liab. Ins. Co. v. Nance, 577 So. 2d 1238, 1240 (Miss. 1991).43 See Huff, 441 So. 2d at 1319 (noting subrogees are substituted in place of the subrogor and may assert any rights the subrogor may have against the particular alleged wrongdoer).44 Employers Ins. Of Wausau v. Dunaway, 626 F.Supp. 1144, 1146 (S.D. Miss. 1986) (citing Oxford Production Credit Ass’n v. Bank of Oxford, 16 So. 2d 384, 389 (Miss. 1944)) (applying Mississippi law) (reading Mississippi law as limiting subrogee’s recovery to the amount of subrogee’s payment). Although Dunaway is still good law, the district court’s reading of Mississippi law was not as persuasive to the Fifth Circuit as compared to the fact that the particular policy at issue in Dunaway specifically provided the right to subrogation was limited to recovery of the amounts paid to the insured. See Audubon Ins. Co. v. Lowery, 9 F.3d 1547 (5th Cir. 1993). Additionally, the Seventh Circuit has disagreed with Dunaway to the extent it precluded the subrogee-insurer from obtaining pre-judgment interest on the money it paid in behalf of its insured. See Am. Nat. Fire Ins. Co. ex rel. Tabacalera Contreras Cigar Co. v. Yellow Freight Sys., Inc., 325 F.3d 924, 938 n.9 (7th Cir. 2003) (“The purpose of prejudgment interest is to compensate the injured party; and prejudgment interest is to accrue from the time of the injury. The insurance company has been deprived of the use of its money from the time that it paid the insured; it has suffered an injury because of the wrongdoing of a third party.”).

14 The MDLA Quarterly • Winter 2012

subrogation commands insurance defense counsel to remain aware their actions will be measured not only by the insured and the primary insurer but now by any excess insurer whose policy may be implicated. Counsel should be cognizant of the fact equitable subrogation is not available where the excess insurer conducted itself wrongfully and where allowing the excess insurer to assert claims against the insured’s defense counsel would result in injustice.45 Lastly, limiting the avenue for claims to

equitable subrogation prevents excess insurers from asserting their remedy until payment is actually made and only where that payment is not considered voluntary.46

Conclusion

The Quintairos decision takes a meandering path to reach a specific result while affording a level of certainty with respect to what claims defense practitioners can expect to face and from whom they

may face those claims. Namely, allowing equitable subrogation effectuates otherwise direct malpractice and negligence claims. It may be the Mississippi Supreme Court endeavored to take the route of equitable subrogation—despite the fact a direct negligence claim may be the simplest, purest remedy—to afford defense practitioners some degree of predictability in the future. Be that as it may, the Quintairos decision leaves intriguing questions to be determined. ■

45 Huff, 441 So. 2d at 1320 (citing Lyon, et al. v. Colonial United States Mortgage Co., 91 So. 708, 708 (Miss. 1922)). Whether these conditions are present very likely will be a factual determination reserved for each particular case. Huff, 441 So. 2d at 1319.46 See Great Am. Ins. Co. v. Smith, 172 So. 2d 558, 559 (Miss. 1965).

On May 14, 2012, after passing in the House 63-56 and in the Senate 31-15, Governor Phil Bryant signed into law Senate Bill 2576 initiating a change to the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation law found in Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-1 et. seq. and overturning court precedent that presumed a claim’s compensability in favor of an injured employee. The changes took effect July 1, 2012 and will apply to all injuries occurring on or after that date.

With the 2012 amendments, “[t]he primary purposes of the Workers’ Compensation Law are to pay timely temporary and permanent disability benefits to every worker who legitimately suffers a work-related injury or occupational disease arising out of and in the course of his employment, to pay reasonable and necessary medical expenses resulting from the work-related injury or occupational disease, and to encourage the return to work of the worker.” Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-1.

Taking a note from the Miss. Code Ann. §11-1-58 which governs medical malpractice, Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-7 now requires a claimant to file along with the Petition to Controvert medical records in support of his claim for benefits. However, a claimant is given a grace period of sixty (60) days after the filing of the Petition to

Controvert in which to file the required medical record(s). The filing of medical records is, per amendment, to be in light of the statutory time limitations found in Miss. Code Ann. §§71-3-35 and 71-3-53.

Apportionment for pre-existing conditions was expanded in that “[t]he preexisting condition does not have to be occupationally disabling for this apportionment to apply. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-7. Changes were also made to an injured worker’s physician selection, in that if an injured worker treats with a physician for six (6) months or longer or a physician performs surgery then that physician is by statue deemed the employee’s choice. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-15. Hopefully this portion of the code will eliminate eleventh hour arguments over choice.

Many of the changes unquestionably favor the injured worker. The immediate, lump sum payment to the surviving spouse was raised from $250 to $1,000. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-25(a). Reasonable funeral expenses were raised from $2,000 to $5,000. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-25 (b). Vocational rehabilitation maintenance was raised from $10.00 to $25.00 per week. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-19. The cap for a disfigurement award was raised from $2,000 to $5,000. Miss. Code Ann. §71-

3-17(c)(24). Also, limitations were placed on attorney’s fees. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-63.

Following Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-7(4) no benefits are due if the use of illegal drugs, the use of a valid prescription medication “taken contrary to the prescriber’s instructions and/or contrary to label warnings” or intoxication from alcohol proximately caused the employee’s injury. Under Miss. Code Ann. §§71-3-121 and 71-3-5, employers now have the right to require an injured employee submit to an alcohol and drug test. A positive test “shall be presumed the proximate cause of the injury.” Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-121. Refusing to submit to such testing raises a rebuttable presumption that the proximate cause of the injury was illegal use of a drug or intoxication. This presumption may be rebutted by the employee by proving that the illegal drug, medication or alcohol was not a “contributing cause” of the accident that caused the injury. Further, the results of drug and/or alcohol testing shall be admissible evidence solely on the issue of causation. Miss. Code Ann. §71-3-121(2). The 2012 amendments removed any ambiguity from the pre-amendment language allowing the admissibility of “employer-administered tests”. ■

Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Law Update

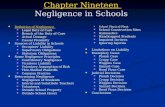

The

MDLA QuarterlyThe pubLicATion of The Mississippi Defense LAwyers AssociATion

Volume 36 • Number 4 WiNter 2012

Issue Highlights: Homebuilder Liability in Mississippi: Why Homebuilders Should Not be Liable for Defective Component Products

No Duty, No Accountability? Not so Fast...... Mississippi Embraces Equitable Subrogation

A Trap for the Unwary: Third Party Arbitration Discovery

The Anna Nicole Show (Still): The Core/Non-Core Dichotomy in Stern v. Marshall

2012 - A Year to Remember