NLR I2, 1960 March-April

Transcript of NLR I2, 1960 March-April

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

1/78

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

2/78

He (Mr. Watkinson) questioned whether the OppositionsCensure motion was on the Government or on the wholeNATO Alliance. He and the Government believed theNATO Alliance was and must remain the core to ourdefence strategy.

If he were to accept the provisions of the motion andsome of the arguments put forward by Opposition members,he would have to go to the Defence Ministers meeting andpropose a complete reversal of present NATO policy(Opposition cries of Why not?)The consequencewould be that I should have done the maximum to weakenthe Alliance.

(Guardian report of the Debate on Nuclear Weaponsfor West Germany. 12/2/60).

IT IS only when we think of the terrible sub-industrialwastes along the stretch of road between Reading andSlough that we have any misgivings whatever aboutthe Third Aldermaston March. In our more sobermoments, everything that has happened in the field ofnuclear diplomacy during the last three monthsconfirms the need for a greater demonstration ofopposition to the nuclear scatter than last years15,000. If anything, the politics of the Bomb havetaken a distinct turn for the worse. Driven by the logicof their own position, the NATO powers are now lollingin the itchy palm of Dr. Adenauer. The only questionnow is whether German nuclear weapons are to be

developed independently by Germany, or be suppliedand controlled by NATO through the SupremeAllied Commander, Europe. If these are indeed thereal alternatives, there is something to be said (at last)for NATO! Dr. Adenauer is now the supreme controllerof the European heartland: and until the United Stateshave completed their crash programme for nucleararmed and powered submarines, the heartland holdssway. Adenauer has successfully dictated the pace ofthe Wests unwilling creep to the Summit, vetted andpruned the Agenda, kept Berlin hanging over theHead of Whitehall and Washington whenever it seemedthat peace might be in the air. Never has the recoveryof a defeated power been so rapid or so disastrous.

In the meanwhile, Napolean IV has touched off hisludicrous nuclear device, scattering the radio-activeparticles of the Sahara to the four corners of theAfrican continent. France, he reports, is bothpowerful and proud. The French Test, dictated by thelogic of the arms race but symptomatic more of theRottenness of France than of her Grandeur, must beone of the greatestand perhaps one of the lastobscenities practised by a European power against thecontinent of Africa. When the history books arewritten in Accra and Nairobi, General De Gaulle will

Why Not?

be remembered as one of the Great Europeans whobrought the terrors of science to Africa when whatthat continent needed most were its benefits.

There is now neither non-Nuclear Club nor balanceof terror. There is no one left to belong to Mr. GaitskellsClub: as a consequence, Labour is without anythingwhich looks remotely like a Defence Policy. Thus,both Mr. George Brown, who believes that NATOis not working fast enough and Jennie Lee, armed withan official West German map showing Dr. Adenauersland-lust for territory which is now Polish, spoke in thename of the Labour Movement. It is all very well forthe Opposition to make a moral show of force againstnuclear weapons for Germany: it is just a bit late.As Mr. Watkinson pointed out, the arming of West

Germany is an essential piece in the NATO jig-saw: toargue against that is to argue against NATO, thepolicy of nuclear deterrence and the whole strategy ofthe Alliance. There is no sign that Labours FrontBench, constantly employed in devising confidentialdefence papers for the North Atlantic Community, aremoving towards this threshold of realism: it is part ofthe job of the Campaign, thrashing about in deeppolitical waters but refusing to swim, to point againand again to the sense in the back-bench cries: WhyNot?

The French Bomb, in its clumsy turn, destroyed thefamous balance of terror which has reigned eversince Britain entered the nuclear lists. The stalemate is

at an end: we have entered another spiral in thenuclear build-up. It is now the turn of the Eastern bloc.Has anyone stopped to think what the world will belike when China and the Ulbricht rgime in EastGermany receive tactical and strategic nuclear devices?

These are the real moving forces in nuclear politicstoday. In that event, it is unrealistic to believe that theSummit, when finally it takes place, will do anythingbut dash the hopes of disarmament and throw a ban onnuclear tests out of the window. The Summit is not amagical enchanted garden, where Dr. Adenauer andGeneral De Gaulle are transformed into peaceful fauns.It is a bleak, exposed place, open to the foul exhaust

from competing nuclear machines set in high gear; aplace where the disillusion of the Geneva Discussionswill be distilled; every exit is labelled Berlin. If theSummit meeting is the tragic failure it gives every signof being, we can expect a renewal of tests in 1961, arapid development of nuclear submarine strategy(Britain is to have her very own second Polaris shortly)and a serious deterioration of the situation, includingperhaps another piece of Soviet brinkmanship over thestatus of Berlin. Compared with this prospect, theSlough-London road looks positively inviting.

1

E d i t o r i a l

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

3/78

2

THERE ARE one or two aspects of the current struggle forthe soul of the Labour Party which have, so far, goneunremarked. The firstand most importantis thescope of the Crosland Revolution. Few of usimagined, when Mr. Crosland began to construct hishouse of theory in The Future Of Socialism, that hewould become the architect of the Party in the sixties.We have continued to think and speak of the reforming,rethinking, revising wing of the Party as a rough-and-ready caucus of practical empiricists.

Far from it. Naturally, a good many Party men havebeen pushed into the Crosland embrace by circum-stancesthe successive defeats, the deadlocked debates,the unpopular policies, the falling membership, theabsence of that god in the electoral machinethe swingNevertheless, what they have taken on to cover thenakedness of their position, are the outer garmentsatany rateof an ideology. Mr. Croslands picture ofcapitalism and the world has behind it the pressure ofan informing vision: it provides the right wing of theParty with a framework for the facts, a logical structureenabling them to explain the past and predict the future.

What we have been witnessing in recent weeks is thetail-end of that revolution. The ideological battles have

long since been joined and won: first Mr. Gaitskellassented, and then, one after another, the up-and-coming intellectuals in the leadershipMr. Healey,Mr. Gordon Walker, Mr. Roy Jenkins. By the timethat Industry And Society appeared at Brighton, in1957, the picture of reformed capitalism, the managerialrevolution and applied Keynesian economics whichMr. Crosland described had already begun to be etchedacross the face of official policy. Mr. Crosland may nothimself have recommended or approved the share-buying scheme: but thisand other proposals of thiskindfollowed on naturally from his analysis. Therecent notes for Political Education Officers in theConstituency Parties affirms that capitalism has been

so reformed that it deserves to be called, not capitalism,but Statisma direct quote from Chapter and Verse inThe Future Of Socialism. What is most important isthat it was the force of this ideology which sustainedMr. Gaitskells hands at the Blackpool Conference.Only the final stages of the campaign remain: toisolate the Left as a fundamentalist rump (what TheEconomist refers to as the Victorian Marxists in theConstituency parties), to popularise the more difficultCrosland concepts and to fight them through into theParty, drawing the Trade Unions into place behind them

(a difficult one, this, for nationalisation is the last ofthe TU shibboleths) and remaking the Party fromwithin. The image will follow, and after thathopefullyvictory. In this difficult task, Mr. Gaitskellcommands the active and continuous (if surprising)support not only of Party moderates, but also of thecentre heavy-weights of the press: The Guardian, TheObserver, The Spectator and The Economist.

What are the essential elements of this new ideology?For a summary of Mr. Croslands theses, applied to themoving arena of politics, one cannot do better than

look over Mr. Gaitskells Blackpool speech. The analysisbegan with the social backdrop to Labours defeatthe changing character of the Labour force. Next hegathered up in one sweep the current myths aboutcapitalism, lending them the force of his moderatepersonality: how it had been tamed from without (theLabour Government reforms) and changed fromwithin (the managers replacing the ravening capitalistsof earlier eras). Then finally, he gestured towardsprosperitythe Welfare State, the comforts, pleasuresand conveniences of the home.

In short, he summed up, the changing character oflabour, full employment, new housing, the new way ofliving based on the telly, the frig., and the car, and

the glossy magazinesall these have had their effect onour political strength.

In the American age just in front of us, whenreformed capitalism will flush out the remnants ofearlier squalor (a point not dwelt on), Mr. Gaitskellcould see little for Labour to do, if it desired to ruleonce more, but follow in the path of the upturns in oureconomic life. (Someday, he could be heard singing in anexclusive interview with The Observer the following week,the swing will come). The future of the Party, then,he cast in this soft mould: defence of the underdog(not a comforting prospect, this, since he had alreadyimplied that capitalism would take care of him too,

in the next round of prosperity): social justicean equitable distribution of wealth and income; aclassless society (surely a misfit, this one). Finally,(a concession to the young Liberals, who picketed theConference with a fresh-faced delight?)equality ofthe races, a belief in spiritual values (a heighteningsentiment in the age of the glossy magazine) and thefreedom of the individual.

This case is tougher than it looks on paper. It has,behind it, the force of circumstances (post-war pros-perity); beneath it, the support of serious intellectual

Crosland Territory

Stuart Hall

A political introduction to the series of articles on Whats Wrong With Capitalism, linking the theoretical

arguments to the current political debate in the Labour Party.

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

4/78

analysis (the managerial revolution and Keynesianeconomics); and before it, the lure of political office(the third Tory victory). What is more, it is firmlyrootedor appears to be soin contemporary facts.In this sense, the analysis is certainly more alive to therealities of society today than the defence which theLeft mustered in reply. The composition of the labourforce has changed: there are fewer farm-workers, more

shop assistants, fewer miners, more engineers, andthese facts are bound to have an effect upon the attitudes,aspirations and expectations of working people. Thefact that this change is so uneven through the countrythe newer technological industries advancing, leavingthe older factories as great gaping social and economicsoressimply masks and confuses this transformation.Mr. Gaitskell may be altogether wrong in his analysisof what working people wantof why, for example,they should always and by definition want a new carmore than they want a better education for theirchildren: but it does not help to assert that nothing isnew under the sun.

Errors and Abuses

The errors in the argument fall into two categories.In the first place, the analysis of capitalism and itstrends appear to us wrong: wrongly conceived, and notborne out by the facts. In the second place, the pictureof prosperity is false, couched in individualist andTory terms, and accepted on their face value, without arigorous examination from socialist assumptions.

We have passed through a period of post-war pros-perity. We have also passed through a period of post-war inflation, never dipping into the deep troughs of amajor slumps, but oscillating, with alarming regularity,

between jumping prices and industrial recession. Theinflation question is still on the agendaunresolved.

What is more, the managerial revolution is not whatit seems. The arguments here are more fully worked outin Charles Taylors article, which is the first of a serieswhich will take up, in detail, the socialist case againstthis challenging ideology. But briefly, the managers,where they are in control, remain the managers ofthe private corporations, the governors of privateproperty in its latest form in an industrial society (themodern firm). The controllers, who own great segmentsof the private sector, and who direct its overall strategythe new capitalists of a corporate economyare

more firmly based now than they have ever been.The managerstame, mild-mannered, public-spiritedthough they may beare the servants (the well-paid,well-cushioned servants) of the system: and the circleof the system remains the accumulation and investmentof private wealth, and the making of profits. Thispicture needs to be much more fully explored anddeveloped. But the essential point is that the making ofprofits is what keeps the wheels going round: this is thedynamic power that drives the economy and sets thetargets for the society.

It follows, then, that we should be driven to ask thequestion, in what direction is the motor running? Whatare the trends, the signs, the portents? And here, a vastarea opens up which is wholly untouched by Mr.Gaitskells deft analysis. We wont recount the majorsocial imbalances which this system of corporate powerestablishes for our society, (Charles Taylor has tried totackle that in his piece); but we can sum up the general

picture of an economy which is capable of dealingprofitably in consumer goods and personal conveniences(though not equitably: the question of economicand class inequalities, which have grown in the lastten years, not receded, must be introduced at this point);but which is incapable of dealing with major areas ofour social life: education, town planning, municipal andpublic rebuilding, roads, pensions, health and welfarein all its aspects, the phased introduction of automationand new technology, the comprehensive re-planning ofindustries which are in decline, and the public services.Gradually, over the next few issues, we shall highlightthese serious contradictions and failures in contem-

porary capitalism, asking, at every point, are thesefailures structural or marginal? will prosperity deal withthese too, as the by-product of affluence? or are theybuilt-in features of the system, which can only bechanged if we are prepared to strike at the very root ofthe matterprivate property and the profit system itself?

Associated with this picture of how capitalism isactually working before our eyes, are three relatedthemes, which we shall develop as well. The first is theurgent political question of the relationship betweencapitalism and military expenditure. The second is thequestion of whether capitalism, as it is driven at themoment, is capable of undertaking the most urgenteconomic task which lies before us: the industrialisation

of the backward two-thirds of the world. The thirdaspect of the problem is the question of whether,by administrative controls and Government inter-ference a capitalist economy can be managed anddirected towards targets radically different from thosewhich the surviving capitalist economies of the worldthe US, Germany, Britain and Franceare steadilymoving towards.

Tory Images of The Good Life

But the earlier pointsabout the misplaced prioritiesof British capitalism, even in its prosperity phase

relate very closely to the lack of socialist assumptionsin Mr. Gaitskells approach to the whole problem.Can we really accept, at this stage in history, the defini-tion of prosperity, of the Good Life, which is nowthe most popular Tory image? If it is true, as we argue,that the system has not and cannot provide for what wemay generally call the public, social, and communityneeds of the society (and the trends, except in particularsectors which capitalism urgently needs, are movingsteadily the other way, both here and in the UnitedStates), how is it that we have been driven into the

3

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

5/78

4

position of basing a socialist case on a capitalist view oflife, a propertied interpretation of human needs?If socialism has roots anywhere, it is in the concept of acommunity of equals, in the moral principle of sharingand co-operation, in the planned command of skills andresources so that they can be made to serve the fullneeds of the community. If we abandon this we, haveabandoned everything for which socialism stands.

Although the provision of an adequate communitylife has often been appropriated by the social demo-crats and the public administrators, and its watermuddied by the concepts of self-help and State assist-ance, it could be the most dynamic and moving humantheme in the restatement of socialism in contemporaryterms. To give this up, and lie down before the advanceof individualism, is not so much a betrayal of the pastideals, as a woeful and disastrous failure of the imagina-tiona collapse before history. Isnt it extraordinary thata serious political partyand a party of the Leftshould set itself as its major task to divest itself of acertain image in the popular mind? One would thinkthat a party of the Left should be constantly searching,analysing, trying to find what is wrong with societyand how it can be put right. The present Labour Partyleadership seems to think that it can dispense with thiskind of fundamental questioning. Does it know how itis going to bring us growth without inflation, have adecent education system, a health service worth the name,how it is going to help the underdeveloped countries,institute a classless society? We have only their say-sothat they are going to do these things, they have neverlet us into the secret of how they are going to beaccomplished. Or can it be that there is no secret?Can it be that they believe, following Mr. Crosland

that a modern reformed Capitalism, suitably guidedwill bring us all these blessings in due course? Thewhole thing represents a tragic failure of political vision,a pigmys sense of the problems before us, and onewhich, ironically, cuts across the most cherished aimof the Labour leadershippolitical office. For, on thisview there is no role for a party of the Left which theLiberals could not fill just as well.

The rising, skilled working class, before whom Mr.Gaitskell makes his obeisances, are simply new groupsof people, with new aspirations and new visions, livingthrough the end of an old society. They are the peoplewhose inarticulate needseducation and welfare and

decent homes and pleasant cities, responsibilities beforethe job and a sense of their own independent dignitybefore lifeare untouched by socialism, as we speak ofit today. They are the people about whom Mr. Gaitskellhas accepted the modern myththe crass, debasedimage of telly-glued, car-raving mindless consumers.Whereas, the task of socialism in the sixties andbeyond, is to pioneer the opening new horizons, theenlarged experience of the world, the new humanambitions which this class, by a tireless, bitter operation-bootstrap, have opened up for themselves, and to give

them political form. The failure of imagination mustthen be defined, ultimately, as a failure of politicalimagination: the incapacity to take the lead, to stand asa political Party and a movement in place of theseideals, to draw in and weld together in political termsthe unfelt, unexpressed, unarticulated needs of ourpeopleas a community.

That is because, to stand in the name of what isgenuinely new in the society (and that is not the way oflife of the glossy magazine) would mean confrontingthe old enemy in new, fancy clothes. In order to establishnew priorities for our society, we would have to controlthe commanding heights of the economy (to use amuch quoted, much maligned phrase of Lenins): notcontrol them at a distance, not ask on bended kneesthat the managers do our job for us, or pray thatthe controllers of the economy will suffer a change ofheartbut control them: as a community. To do that,would in fact mean the re-application of the principleof common ownership to our economic thinkingnot

as a well-worn shibboleth which must be defended,like Buckingham Palace, because it is therebut becausewe cannot make a system which is geared to go forwardin one direction reverse itself, unless we are preparedto work it ourselves, unless it is responsible to us.This is the caseor the elements of itfor commonownership, and if we are going to march forward inour serried ranks in defence of Clause 4 of the Con-stitution, without going right through, from scratch, tothe reasons why we need common ownership, the fightin 1960 will be as sterile as the defence of the Leftproved to be at Blackpool in 1959.

The ends are contained by the means, then. If it

is really a classless society we want, we must face up tothe fact that the system which we are trying to tame,which provides Mr. Macmillans kind of prosperityon the one hand, is what generates class power on theother. Behind the back of the Welfare Revolution, arevival of the class system has silently taken place: andthe more profitable it is to supply the consumer needs ofthe community, the more robust the owners, controllersand managers of the system will become, the soundertheir social position, the more stable their personalprospects, the greater the gaps in income and privilege,the more divided the society. Are Mr. Gaitskell andMr. Crosland prepared to ignore forever the increasingstability and confidence of our new ruling lite in the

country? and its effect on the culture of our society?When is an Executive speech at Conference going tobegin, Let us really look at what has been happeningwithin the commanding heights of the economy, let usdiscuss whether we are in fact moving towards a morehumane and equal society. . . . Then, at last, theeconomic factsanalysable in any breakdown ofincome, wealth and privilege in the Blue Books,demonstrable before our very eyeswill have brokenthrough into politics, and we can begin to discuss justwhat we are going to do about it.

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

6/78

THE FIFTIES have ended in a mood of celebration andself-congratulation. We felt we had a right to be proudof our achievement. Most people clearly felt that some-how we had managed to create a more humane, justsociety: one, if not fit for heroes, at least fit for average,normal human beings. A. J. P. Taylor went so far asto claim, in the New Statesman that we are enteringUtopia backwards.

What justified all this? Whatever the fifties brought,it was certainly not a humane and just society. Quiteapart from Suez, Hola and Nyasaland, can we call a

society which was so incredibly stingy to its people inold age just? And as for a society fit for humanbeings. . . . Why on earth should we be satisfied with apublic expenditure on education of 670,000,000, whenwe know that many schools are tumbling down, andthere are 40 children to a classroom? Because wecould not afford more? But we could afford to spend400,000,000 on advertising. Why do we begrudge theHealth Service its 700,000,000 when our hospitals soobviously need rebuilding? Because of a pressing lackof resources? Why then has the refrain been, we havenever had it so good? If we are so short, must thepackaging industry really eat up 500,000,000 a year?Brian Abel-Smith has calculated in Conviction that, atthe present rate of construction, six new Shell buildings

will go up before we have rebuilt the hospitals whichnow need rebuilding: and that by then, the date will be2160!

There are in Britain today wards (in mental hospitals)which havent been papered or painted in this century.There are ward kitchens without refrigerators, ovens orhot-plates. There are sluices without bedpan washers.There are patients being fed at a cost of 14s. l0d. a week.

(B. Abel-Smith, Conviction, p. 64)

One has only to scratch the surface of our society tosee that our priorities are all wrong. They are not onlyunjust: they are divorced from any real sense of humanneed, and strikingly irrational. It is not just that toolittle is spent on welfareif we were an underdeveloped

country, we would have to put up with that. It is thatour society puts production for profit before welfareevery time.

The problem is not just that the priorities areirrational. They also reflect the kind of society that weare, and are becoming more and morea society wherecommercial values are uppermost, where what counts iswhat sells.

Isnt it possible for the buildings of the Welfare Stateto keep pace with the buildings that house privateenterprise? All around us we see palatial prestige offices,

new shops, new factoriesputting to shame the grubbyold institutions of welfare . . . I read in the Times of12 May, 1958, that a bank has opened a new branch inPiccadilly Circus. The interior decoration incorporatesred marble quarried in Oran, ebony black granite fromSweden, Italian glass mosaic, delabole grey and Italianslate and afromoria, and linoleum patterned with thebanks crest . . . there will be no marble for the hospitalsnot even glass mosaics. Use them to attract casualcustomers to the bank. Dont waste them on worriedmothers waiting all morning in the out-patients departmentof the hospital.

(B. Abel-Smith, Conviction, p. 65)

These false priorities are built in to our very notionof prosperity. The growth of prosperity over recentyears is measured almost entirely in terms of the risein the Gross National Product and the number of TVsets, washing machines, cars and so on. Now theseconsumer durable goods fulfil real human needs: butit is surely wrong to speak as if allor even the mostvitalhuman needs can be met by an increase in theproduction of consumer goods. And of course no onereally believes this. Yet, when Mr. Macmillan wants tobring home to us that we have never had it so good, heis only able to talk in terms of the telly and the washingmachine. During the credit squeeze, much more fusswas made about the restrictions on HP credit, than

about the cutbacks in public investment: althoughevery member of the public who travelled by publictransport must have felt the pinch. Why this fetishismof the consumer durable? Because we live in a businesssociety, and this means that the things we produce forsale on the market are seen as intrinsically moreimportant than the services we provide for ourselvesas a community. Production for profit is considered themost important economic activityoften as the mostimportant activity of any kindin our society.

Take education. We cannot bring ourselves to spendenough public money to reduce the size of the classesto 30presumably because we cannot impose anygreater burden of taxation. Yet we give relief to those

individuals who pay for their childrens public schoolfees, and to the private corporations which pourtax-exempt funds into the public schools.

And why, in this day and age, have the corporationscome to bail out the public schools? This is not just aquestion of class solidarity. It is also because the publicschools provide the cadres for business, the essentialmanagerial elites: and since the prioritieseven ineducationare established by the needs of the privatesector rather than by the needs of the community ingeneral, a new ICI science block at Eton gets priority

5

Whats Wrong With Capitalism?1

Charles Taylor

Charles Taylor tackles the problem of the false priorities of capitalism, particularly in the welfare sector, and asks

the fundamental question: are these false priorities structural or marginal to capitalism?

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

7/78

over the reduction of the size of classes in theWandsworth Secondary Modern.

Suppose we were to re-affirm that education shouldnot be simply designed to make people more pro-ductive, but that it has a human value, that its role is togive people a minimum standard of culture and thepower of understanding and articulating their ownexperiences, both personal and social? But the humanvalue of education is constantly affirmed in seniorcommon rooms, in conferences and reports, in after-dinner speechesin fact, everywhere except on theoperational level, where money is raised and spent.At this point our ruling lite, who have an almost reli-gious respect for the Greeks, and some of whom evenkeep a volume of Thucydides as bed-side reading, canimmediately find all sorts of other things to do with themoneyincluding even making Britain the nth powerto send up an earth satellite.

Of course, something will be done in the future abouteducation. But what? We need more techniciansasSputnik I conclusively provedand we may get them.

It is significant that it was Sputnik I and not the stateof our culture or the rate of juvenile delinquency whichproduced this re-appraisal. Industry needs technicians:and so, we are going to get a rapid improvement intechnical education, although we have not touched thequality of technical education in the Secondary Modern;we are still not sure when we shall get around toextend the school-leaving age to 16, and we have nottaken even the first steps towards making this extrayear of schooling something which would be welcomedby secondary school children or teachers. The CrowtherReport is hailed as a great advance because it recom-mends the extension of the school-leaving age in thelate sixtiesalmost a quarter of a century after theEducation Act which projected it.

When we consider building, we can see that the falsescale of priorities affects more than the welfare services.We see the same squalor in the public sector, contrast-ing with lavishness in the private. Mr. Jack Cotton willspend 7,000,000, if they let him, on 3/4 of an acre atPiccadillyenough to build an LCC housing estate of1,750 flats inside London or of 3,500 outside. And noone can say that we need Mr. Cottons monstrositymore than a new housing estate. We need it as we needa hole in the head.

It is not only a question of contrasting the resourcesused up in private and public housing. What has

happened to the ambitious schemes for town planningwhich were abroad at the end of the War? There wereplans for the major cities which commanded a great dealof public support. We seemed to recognise the fact thatcities are not merely places where people find shelter,work and amusement, but human environments inwhich the majority of us spend most of our lives. Theproblem was how to concentrate the technical skills ofarchitecture and town planning, with the necessaryeconomic resources, to create a human environmentfor us to live in. We recognised that beauty is something

essential to man, which he needs in his environment,not merely as a luxury in his off-hours. And yet, whathas happened?

Exactly the opposite. Huge tracts of all our citiesremain squalid and ugly. The new buildings more oftenthan not increase the ugliness. A larger and larger numberof shapeless masses choke the city centres and destroytheir line. The reason is not hard to find. To have ade-quate town planning, we need a much larger publicsector, and more municipally controlled development.Certain areasfor instance, Notting Hill, the SouthBank, Piccadilly, which ought to be planned as singleunitsare too large for a single developer. Yet allalong the line we have been forced to retreat. The SouthBank site was to include Government offices, a NationalTheatre, a hotel, riverside gardens, a Science Centre.All we have so far is the monstrous Shell building.The LCC now tells us that the Barbican schemewhich attracted worldwide commentis to be the lastof its kind. The rest of the city is to be abandoned tothe jungle of the speculator and private developer.

But why has the LCC retreated? The fact is that thereis no public money available for planned communitydevelopment. Government permission is necessary toborrow money, and in recent years, the local authoritieshave been forced on to the open market. Here interestrates are high, and investors reluctant. Further, theabolition of the development charge makes the costof land purchase prohibitive (see The PiccadillyGoldmine for a more detailed development of thisaspect). And yet, no one can plead that the resourcesfor development do not exist, for the buildings aregoing up in Notting Hill and the South Bank anyway.Of course, the Notting Hill development will concen-trate on offices and shops, leaving the slums of Talbot

Road, where racial tension is rife, to decay. But thatsthe way the wind blows. The LCC did not make thatwind: it has only been guilty of weakness and lack ofimagination in bending to it.

Who Sets The Priorities?The real question is, who sets the priorities and why?

Why is public building squeezed, and the planning ofwhole areas as units thwarted? Because the interests ofprofit predominate over the interests of the com-munity, in building as in education. The lesson of theMonico site at Piccadilly is not that some private

entrepreneurs lack taste. Some public bodies do as well.The simple fact is that plans for the building were drawnup in order to secure maximum profit for the developerand no other consideration was permitted to intrude.It was never conceived as part of the human environ-ment of the people who will have to live with Piccadillyfor the rest of their lives. It was simply a giant money-spinner(as the examining counsel said, the biggestaspidistra in the world).

It is not simply a matter of the aesthetic values ofspeculators. Speculation in land values has driven the

6

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

8/78

price of such sites so high, that planning has becomealmost impossible. On Piccadilly Circus, for instance,land is worth 100 per square foot: a small motor car,cramming the narrow entry into the Circus, is standingon 2,000 worth of asphalt. This ensures that the citywill develop in one direction onlyexpanding dormitorysuburbs farther and farther around the fringes of the

cities, giant commercial office blocks clogging up thecentres; becoming, at nightfallafter the pedestriansand commuters have fought their way down narrowstreets into packed tubes, or been brought to a stand-still in bumper-to-bumper traffic on congested roadsdim, deserted urban canyons. So thatirony of ironiesthe speculators can claim to be doing everyone apublic service by livening up the deserted city centreswith garish, monumental advertisements.

Why are our priorities so wrong, so obviously wrong?And why do we tolerate them? During the last election,and after, the fault was laid at the door of the electorate:theyre self-satisfied, complacent, all right, they dontcare. But in what sense is this true? Did the electorate

actually vote, in October 1959, against public housing,against planned redevelopment, against better educa-tion, against an adequate health service, against anextension of the youth serviceand in favour of theprivate speculator, in favour of more advertising, thepublic schools and dormitory suburbs? Put this way,the whole case of All right Jack needs to be radicallyre-examined. Are these the issues which were putbefore the electorate at the Election? Is that what Mr.Gaitskells programme of moderate and practicalreform was about?

A scale of values which places a higher priority onproduction for profit than on community and social

needs is, surely, rooted in the economic order ofsociety itself. Twenty years ago this would have seemedan obvious truth. And yet, today, it is widely believedthat these obvious maladjustments in capitalism are notstructural but marginal: that is, that a few more yearsof prosperity will see us through. This belief reflects anumber of important assumptions which many peoplemake, about capitalism and its trends and tendencies.It is worthwhile to disentangle these arguments, anddiscuss each in turn.

The Trends in CapitalismIs it true that, if we extrapolate from present trends,

we have every right to expect capitalism to clear upthese little local difficulties in the next ten years?In 25 years time, if a succession of Tory Chancellors arevery lucky, we shall have doubled the standard ofliving. At least this is the expression used. The naivemight believe that this entails a doubling of the publicservices as well. Only personal consumption andprivate savings will double: public investment may well

trail behind, as it has done in recent years.In fact, in the last nine years of a Conservative

Government, the trends have all been the other way.They have increased the charges for medical, and dentalcare, the cost of school meals; cut back the buildingprogramme for hospitals and schools; made a directassault upon education and the youth service through

the system of Block Grants to local councils; they havemade it more difficult for local authorities to raise fundsto undertake development and housing projects; theyhave fallen down on their roads programme, at thesame time as they starved and cut public transport.Why should these trends give us any hope or confidencein the capacities of capitalism to right these wrongs inthe future?

We are not moving in the right direction. But perhapsso many people feelsomething will intervene tochange the present trend of things. But the question is,what kind of change will be adequate? And the answerto this question will depend on whether we think that

the present system of capitalism tends to re-enforce theexisting priorities, or whether capitalism has alreadybeen reformed from within.

The reform of capitalism from within is a commonthesis on the Left today. The system, Mr. Gaitskellimplied in his speech at Blackpool, has been reformedby state intervention and the establishment of a mixedeconomyachievements which the Tories dare notundo. Industry, Mr. Crosland argues, is no longer runby ruthless capitalists bent on the maximisation ofprofit, but by humane, public-spirited managers. . . .Business leaders are now, in the main, paid by salaryand not by profit, owe their power to their position inthe managerial structure, and not to ownership.(C. A. R. Crosland, The Future of Socialism, p. 34).It is to this changeit is impliedthat we owe thesocial justice and prosperity of the post-war years:given time, managerial capitalism will take care ofeducation, housing and re-planning as wellwith somepublic-spirited Wykehamists on the Treasury Benchto guide its hand.

The managers of industry are by no means anindependent class able to cut itself free of the institu-tions which employ them. In trying to discover what sortof capitalism we are living through, there is not muchpoint in scrutinising the personal motivations of thenew managers. As a matter of fact, some very fine

motives have actuated the leaders of business, pastand present: an interest in the product itself, or thesense of performing an important social function.But the important point is that, in a capitalist economysuch as ours, where the dominant institutions are thelarge corporations, the main criterion of success orfailure is profit. In this respect, it can hardly be arguedthat our society has changed. Indeed, with the declinein the influence of non-economic institutions, such asthe churches, and the shift of ruling-class power towardsa firmer base in the corporations, it could be argued

7

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

9/78

that our society is, if anything, more homogeneouslycapitalist. The point is not, therefore, whether theindividual managers are interested in gain or not: butthat the survival, and even more the success, of theinstitutions they are paid to serve depends on making aprofit. Whether by ruthless competition or the expense-account lunch where things are thrashed out, thefinal aim is the accumulation of capital. This drive maybe tempered by more humane standards imposed bythe rise of the labour movement, and by the increase ofwealth in the last decades, but it is only tempered. Themain motive remains profit in the old sense.

Thus, whether we consider the managers to be a kindof secular priesthood, as servants of the controllers oras identical with the capitalist class, the criterion ofsuccess, and hence the motor force of the institutionswhich employ them is profit. The firms must show aprofitwhether that profit is then distributed toshareholders, or put to reserve. Capital and assets mustbe maintained and expanded: existing markets extendedand new ones opened up: capital privately accumulated

and re-invested. If the managers are a new priesthoodwithout personal interests, then they are priests in theTemple of Mammon.

Has The Profit Motive Disappeared?

Why then is it commonly held that capitalism and itspriorities have been radically altered? Crosland himselfaccepts that profit remains an essential personal andcorporate incentive (p. 35). The confusion arisesbecause the link between profit and capitalism is notseen, because it is a mistake to think that profit, inthe sense of surplus over cost, has any special or uniqueconnection with capitalism. On the contrary, it must bethe rationale of business activity in any society, whethercapitalist or socialist, which is growing or dynamic(Crosland, p. 35). This sounds terribly plausible untilone tries to think what it really means, and then onesees that the whole thing hinges on a confusion ofthree quite distinct senses of the word profit. In thefirst sense the word means simply surplus over cost.Read in this way, the statement is a truism. Any societywhich is growing or dynamic must create a fund forinvestment, and one of the best ways of doing this isto charge more for goods than they cost to produce.The Soviet Union does this, taking back through theTurnover Tax enough for new investment and welfare

spending.So far so good. But when Crosland speaks of arationale of business activity, he is speaking of profitas an incentive. And here we come to the second sense.If Crosland means profit as incentive for individualsto do productive work, then again hes probably onsafe ground. It is highly likely that we shall always haveto remunerate individuals on an incentive basis, i.e.more pay for more and better work, more pay (orsocial bonuses) for special responsibilities or particularlydangerous kinds of work.

But the sense of profit which is crucial here is thethird one. This is the sense in which we speak of it as theincentive for the productive activity, not of individuals,but of units of production or firms. Here we are nolonger talking about how the individuals are re-munerated. The workers may be badly paid and themanagers may be Spartan in their self-denial and single-minded concentration on productionthe image of theclassical capitalistbut the rationale of the firmsactivity is still profit. In a capitalist society profit in thissense plays a pivotal role, because the conditions ofsurvival are such that a firm must either make a profitor go under; and, more important, the motivation forgrowth, for better or more production, is the prospectof greater profit and hence the accumulation of capital.

Now profit in this sense is not a necessary feature ofall possible societies. On the contrary we could have asystem where the units of production (the firms)operated in order to ensure a good and rising standardof living to those who worked in them, but where(a) the conditions of survival were not such that the

firm had to produce the things that would sell,whether they were useful or needed or not, and(b) where the motivation for growth was not accumula-tion but the satisfaction of doing creative and sociallyuseful work, the recognition of the society and somegreater remuneration for all the individuals involved.

We could have such a society, and if we are to get ourpriorities right, we must have it. For it is the existenceof profit in the third sense, of the profit system,which is at the root of the problem. Under a profitsystem, the criterion for what is worth producing iswhat will sell, and hence make a profit. That is thereason why we have the fetishism of the consumerdurable we spoke of earlier. But this is the leastserious consequence. More important is the fact that asociety dominated by the profit system must tendalmost irreversibly to put production for profit first.As long as the main incentive is accumulation it willalways be very much in the interest of firms to pre-emptresources for production for profit, at the expense ofthose enterprisesand they include our essential welfareserviceswhich cannot produce a profit, and whichtherefore will not be defended by a vested interest.That is the reason why we spend nearly as much, throughadvertising, stimulating unfelt needs, as we spend oneducation, why the cars are produced without the roadsto drive them on, why Mr. Cottons monsters go up

while the LCC housing projects get postponed.If this analysis is right, if these faults are structuralfaults in our system, it is difficult to see where theinternal reform within capitalism is going to come from.For as long as the motor of the firm is profit, theprimary responsibility of its managers is limited tothe firm and its growth. Of course, the rise of theLabour Movement has forced more civilised and humanestandards on to management. Many firms now takecare of part or all of their employees with everythingfrom superannuation schemes to cheap housing, and

8

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

10/78

more firms will certainly do so in the future. But thereis a great danger in exaggerating this change, welcome asit is, into a supposed reform of the system. For theseschemes do not begin to solve the problem of providinga decent standard of welfare services for the wholecommunity. They serve, on the contrary, to accentuatethe double standards in welfare which are more andmore in evidence in our society, a system in whichworkers in the less profitable industries, and non-profitmaking nationalised industries, not to speak of thesubmerged fifth, will go to the walland moreoverwhere their distress remains unnoticed amid thegeneral rejoicing over progressive management. Ifthe Labour Movement ever decided, on the plea thatcapitalism was reformed, to confine itself to a strugglewithin the system to make management more progres-sive, it would be in danger of renouncing one of thefinest parts of its tradition, the struggle to establisha responsibility by the whole community for all itsmembers for the provision of vital human needs. Itwould become what it is already suspected of being in

some quarters, a loosely bound congeries of pressuregroups.

This principle of community responsibility is thesocialist principle behind the whole concept of welfare.The welfare state was only a beginning: the troubleis that the concept of welfare and community respon-sibility has fallen dead in the hands of the Labourrethinkersso that it now appears to be another wayof defending the underdog in society, rather thanbeing extended into the revolutionary and challengingconcept that it is.

Controlling the Machine

This is all the more worrying in that it is happening ata time when welfare is retreating and the individualistethic of capitalism advancing. It is not only that welfareservices have been nibbled away at the fringes; it isalso that we have seen a refurbishing of one of thehoariest myths of classical capitalismthat the choicesmade by the individual consumers on the market aresomehow more free and therefore finer and morevaluable than those made by the community as a whole.This idea, summed in the slogan Tory freedom works,is a debilitating myth. For the really vital choices which

we are discussing here are forever excluded from therealm of free choices. The notion that we could goabout setting our basic social priorities via the market asconsumers is nothing short of absurd. How would theconsumer go about choosing to have more educationand less advertising? The former is not a commodityon the market and the latter is the result of decisionstaken in industry to affect his spending, not the otherway around. How could we choose to have less Monicooffice buildings and more municipal housing? Can wedo this as free consumersvia the market? The

whole idea is meaningless. If the question of what ourcities are going to look like in fifty years is left toconsumer choice, the cities of 2010 will reflect, notwhat we want, but what the speculators choose we shouldhave.

But how, in face of the profit system are we going toget our priorities right? This is, or should be, one of theburning problems of the Left to-day. But the tragedyis that the leadership of the Labour Party is so pre-occupied with the task of disengaging itself, by the mostdevious possible means, from the image of nationalisa-tion, that they cannot even get the problem in focus,much less begin to answer it. They seem to haveswallowed wholesale the view that capitalism hasreformed itself, that the existence of the profit systemis no longer relevant to our social problemsthe viewthat is summed up in that wonderfully question-begging sentence in Industry and Society: Underincreasingly professional managements, large firms, are,as a whole, serving the nation well (p. 48). But onceone has ones head firmly buried in this sand, all clear

thought about the problem becomes impossible. Onecannot even raise any questions about the tendenciesof the system, one can only speak about the decisionsof individuals.

The major scapegoat is of course the Tory govern-ment. But here, again, one misses the point if one seesthis in terms of individual decisions alone. The re-gressive legislation of the Tory government doesntspring from a kind of malevolence or egocentricity onthe part of the Front Bench. To believe this is funda-mentally to underestimate the Tories. They are onlyadministering a system which makes certain demandswhich have to be met. When the Rent Act, for instance,was hailed as courageous, this was not sheer humbug.Landlords, like other entrepreneurs, require a certainprofit if they are going to fulfil their economic function.It therefore could be seen as courageous to courtunpopularity in order to pay this price for the greatergood.

It is as if the Labour leadership saw our economyas a kind of machine which could be made to operatein any desired direction, depending on the intentionsof those who are at the levers of control. With aLabour government we could have the whole thingchurning out greater welfare. But if one needs an analogy,our system is much more like a live beast than a machine.And this is why, side by side with a bland optimism

about Labours goals, went an extraordinary caginess,shading into embarrassment and finally panic, abouthow they were to be achieved. The problem was thatany plan which could actually have achieved even thesemodest reforms would, if announced, have evokedhowls of rage from the beast and frightened not onlythe electorate but the prospective tamers as well. Theincome tax pledge was like a final confession of impot-ence, and this is how, it seems, the electorate took it.

And what are the levers of control that we have atour disposal to shape the mixed economy to our ends?

9

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

11/78

10

There are the resources of economic planning, there isthe influence of the public sector and there are thepossibilities of taxation. It is worth taking these threein turn to see how they could be used to carry throughan attempt by the community to take these decisionsinto its own hands.

Whenever people talk about planning, not least theLabour party, they speak of a whole barrage of controlsfrom investment allowance to exchange controlswhich are designed primarily to increase investment andefficiency while avoiding the pitfalls of inflation or aflight from Sterling. If all these workedand this isdoubtfulwe would no doubt have a more dynamiceconomy, becoming a little more like West Germanyevery day. But the kind of planning necessary to reverseour priorities must involve somewhere a major re-allocation of resources, i.e. it involves more thaninducing people to do what they are doing to-day onlymore efficiently and on a bigger scale.

It is when the government tries to force corporationsto do what they are not doing, that we get the trouble.

The Tory governments remedy is simple: you justhave to make it worth their while. Loans, grants, orders,must be given from the public purse until the ideabecomes worthy of consideration. In this way Colvilleswas induced to place their new mill in Scotland, and theBMC the same. In this way too, a rationalisation of theaircraft companies was effected. But wherever thehand-out cant be applied, the government pleads invain. The Chancellor has been knocking on the door ofthe private corporations to reduce prices for severalmonths, with no perceptible result whatever. TheMinister of Housing has been abjuring speculatorsnot to put any more office blocks in the centre ofcities: they continue to go up. And so on.

The System Resists Planning

There are exceptional circumstances, such as war-time, when planning of a tougher kind is tolerated. Butthe acquiescence can only be bought for this by placingthe managers themselves in the key positions. Rogowand Shore in their Labour Government and BritishIndustry have admirably documented this well-knownstory for the post-war period before even these controls

were dismantled. The authorities, therefore, began tobehave and look more like trade associations andoligopolistic combines than arms of the state. Thewhole system couldnt help breeding inefficiency and,within the terms of the system, had to be dropped.No one, least of all Labour has suggested its revival.

The brute fact about the profit system is that itresists any planning which would take the real decisionsabout the allocation of resources away from it.Whitehall interference would mean that the scope forexpansion and accretion of profit is held back, that some

corporations are disadvantaged. It would mean cuttingdown the very freedom to do what the corporationsmust do if they are to be successful by the only criterionof success that can be applied to themthe freedom toaccumulate. Thus, public planning and control strikeat something more than the wealth of the controllers.It strikes at their very raison dtre, at the myth of their

social role, at their position in society as bosses,indeed at the whole notion of a society with bosses.It will therefore be resisted by them with a force out ofproportion to the loss of income involved.

The governments role is therefore restricted tocontrolling the over-all level of activity, so as to avoidinflation in one direction and mass unemployment inthe other. The Tory Governments weakness for theweapon of monetary control is not the result simplyof some nostalgic fixation on the golden age of BankRate before World War I. It is because monetary policyis the only way that they can control the total level ofactivity in the economy, without interfering withparticular decisions taken in the private sector. If

some firms go to the wall or cut down investmentbecause of a credit squeeze, at least it will not bebecause the Government has decided to cut investmentin that particular sector. The market will decide. This isthe only real planning that we have.

The Public Sector?

What of the public sector? Isnt this the thin end ofthe wedge? In fact, of course, the public sector in themixed economy has been dictated to by the privatesector, rather than dictating the priorities and directionsof the economy. The private sector has successfully

prevented the extension of the public sector, starvingthe publicly owned airlines to cushion the privatecompanies, cutting in on the railways and setting freeroad transport. If the private sector is to obey the lawsof the system, it must be free to eat up resources whenand how it sees fit. So that, in the fight against inflation,it has always been easiest for the Government to slashinvestment first of all in the public sector. Only muchlater does the credit squeeze begin to work in theprivate sector. This process has been going on, in allthe nationalised industries, right throughout the lastfive years. At the same time, the public sector is usedas the pace-setters in resisting wage claims throughoutthe economyas happened in the case of London

Transport in 1958, and as is happening on the railwaysnow.

All corporations are united in opposing the extensionof the public sector or even the allocation of greaterresources to iteven those which are not toucheddirectly by the proposed expansion. It should be irrele-vant for the building trade whether they were contractedto build houses by a local authority or prestige buildingsby Shell. But it does matter to Shell: and a kind ofrudimentary solidarity plays here, not unmixed withthe prospect of greater and quicker profit.

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

12/78

At the same time, the private sector requires a publicsector, provided it is not too large. The public sector,after all, is the least painful place to cut back on in timesof inflation. It provides a cheap and efficient power andtransport system. It is also an essential stabiliser to theeconomy, provided it is docile. This means that thepublic sector must accept to have its investment axedwhatever the consequences, and refrain from siphoningresources away from the private sector. It must be keptgenerally subordinate. This explains the absurd pricingpolicies imposed on the nationalised industriesi.e.that taking one year with another, they should not berequired to make a profit. The only branch of publicexpenditure which arouses no hostility from theprivate sector is in the massive and profitable expendi-ture on defence.

So the weapon of taxation becomes our last resort.But here we are in a cleft stick, as Labours electionpledge showed. Under the Conservatives a ceiling totaxation has been fixed and will be respected. Would itbe different under Labour? Even Mr. Crosland has

admitted that he cannot conceive of the private sectoragreeing to a dramatic rise in taxation. And we are notjust talking here of personal income tax. In the end, wewould have to transfer resources out of the privatesector, and hence reduce profit, in some cases drama-tically. They wouldnt stand for it. And in a sense theyare right. The motor of the system is after all profit,the private accumulation of capital. If we impose veryheavy taxes, we are siphoning off the fuel from thismotor. We cannot expect it to drive on regardless. At acertain point we will tax the private sector so heavily,that we will affect its capacity (or more important, itswillingness) to invest.

No one knows at what point this would occur.But the possibilities are unnerving. The ultimate weaponof those who control capital is not just that they sit on it,(i.e. induce stagnation), but that they export it. Every-one remembers the capital flight of 1951 which helpedto bring down the Labour Government. And thethought paralyses the will. If we are going to try to takethe profit out of the profit system, we shall have sooneror later to replace it. We shall have to raise the questionof common ownership again in a different context.

The Inhuman Priorities

The present priorities are wrong. Centrally, struc-turally wrong. And yet, at the same time, they appearendowed with an apparent inevitability. No one wouldgo out of their way to defend them. Yet it is quite clear,that when the Election came, very few people hadconfidence that Labour knew how wrong they were, orwhy they were wrong, or any proposals for settingthem right. A majority of the electorate agreed to Mr.Gaitskells modest proposals. But they were not sureenough of Labours capacity to bring them about torisk economic mismanagement or to throw their own

tangible prosperity into the melting pot. Most peopleknew that if we pushed the priorities too far, we mightkill the goose which is now, after all, laying the goldeneggs of prosperitycapital. Did Labour have a gooseof its own?

Are They Inevitable?

The sense that the present priorities are inevitableis increased by the fact of advertising. It is not simplythat advertising ensures an expansion in the demand forconsumer goods. It is not even that advertising has hadthe effect of creating a certain image of prosperity, andeven sometimes of the Good Life. It is because thebombardment of the public consciousness with a certainkind of product inculcates an unspoken belief about whatthe progress of our civilisation has made possible, andwhat we just simply have to put up with as the best of abad job. The latest gadgets for automatic cups of earlymorning coffee fall in the first category: the miserablestate of our hospitals falls in the second. We are

rarely, if ever, told that we could have a decent educa-tion, modern hospitals, or clean and beautiful cities.

In fact, we are led to believe exactly the opposite.The public and welfare sectors are continuously assoc-iated with what is drab and uninteresting and distant.But here is the vicious circle. The drabness of the LabourExchange, the hospital out-patients and the railwaywaiting room is due to the misordering of priorities,and the inevitable tendency of capitalism always toskimp on this kind of unnecessary expenditure. Toaccept these conditions is to accept the society and itspriorities as given.

The only way that we can really get our priorities

right is to do away with the dominating influence of theprofit system, and to put in its place a system primarilybased on common ownership. Any attempt to adjustcapitalism to the needs of the community will bebrought up sharply against the innate character anddrives of the system itself. Certainly it is true that, givencommon ownership (not state monopoly), we shall haveto experiment with different forms of control, so asto draw upon the social responsibilities of people insuch vital things as what kind of education they givetheir children, what sort of houses they live in, where thehospitals are placed, when the roads will be built, whatthe city will be like to live in fifty years from now, what

proportion of our national resources go to consumergoods, what proportion to investment and to welfare.These ought to be the really critical democratic decisionsin society today. We do not want to replace capitalismby yet another form of paternal bureaucracy. Thatis the really important challenge to democratic socialismtoday. But before us stand the inhuman priorities ofcapitalism: the only political question is how we canunderstand and change them in order to achieve anenlargement of freedom and responsibility, and a greatercontrol by people over the society in which they live.

11

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

13/78

12

PICCADILLY

GOLDMINE

DUNCAN MACBETH

In this article, Duncan Macbeth develops thecase against Capitalism in terms of urban planning

and reconstruction.

Jack Cottons proposed Monico

building:

The biggest aspidistra

in the world . . .

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

14/78

BEFORE THE war capitalist society exhibited obvioussymptoms of diseasethe feverish stock exchange boom,the slump, mass unemployment, the derelict areas,poverty in the midst of plenty. Today these symptomshave largely (though perhaps temporarily) disappeared.The stock exchange boom is with us, but not the slump,and the Conservative Party has been swept back topower on the full tide of prosperity. It is less obvious,but nevertheless true, that the kind of prosperity weare experiencing can, like poverty, be a disease, andgive rise to forms of crisis as difficult to solve as thosewe experienced before the war.

The unlimited proliferation of cancer cells can destroythe human organism. The unlimited proliferation ofprivate motor cars and speculatively built office blockscan strangle and destroy the city, disrupting its centreand dispersing its inhabitants throughout the country-side. For the city, too, is a living organism requiringcertain conditions and a certain discipline for healthygrowth and evolution. A building and a stock exchangeboom may raise land values in city centres to such

dizzy heights that no public authority can afford tocreate out of the present chaos new, more spacious,beautiful and efficient cities.

The period of post-war reconstruction is nearly over.The problem today is the renewal of undamaged citiescontaining buildings of every age and condition.Most of the new office blocks and shops are replacingolder buildings which have been torn down to makeroom for them. Sometimes these buildings have beenworn out and ripe for replacement. But often they havebeen sound, if old fashioned; the new Vickers sky-scraper in Millbank is going up on the site of Victorianflats that were in good condition; St. James Theatre

and the Stoll (built only 50 years ago, and one of themost modern theatres in London) have come down tomake way for offices. The same process is taking placein all large towns where there is a big demand for officeaccommodation.

The motive power behind these developments isprofit, and the decision whether to redevelop a particularsite or not depends, not upon the age or obsolesence ofthe buildings to be demolished, but upon the differencein value between the old buildings and the new ones.Where the operation of demolition and reconstructionshows a sufficiently large profit, then no matter howgood the condition of the building, no matter howsocially important its purpose, the developers move in.

The process is succinctly explained in TechnicalMemorandum No. 9 on Central Areas, circulated toplanning authorities by the Ministry of Housing andLocal Government last year:

For the kind of development normally undertaken byprivate enterprise (though on occasions by public bodies)the developer is normally interested only in the profit-ability of the project: whether, that is, the money values(benefit) will be sufficiently above the cost of the land andworks to make the project worthwhile.As profit is the mainspring of development, capital

is concentrated where the profits are greatest; and that,today, is in the central areas. Developers cannot or willnot rehouse working-class tenants, because there is noprofit in it. Developers are interested in the prosperousshopping and business districts of prosperous towns,but not in Poplar, Bethnal Green, Dewsbury or Nelsonand Colne. So the order of priorities that would bedictated by any rational assessment of social need isreversed. More and more capital is poured into alreadycongested central districts of London, Birmingham andother prosperous towns, while the public authoritiesare starved of the capital to redevelop the rottingindustrial and working-class areas, particularly in theMidlands and the North, and are unable to provideschools, houses, roads, parks.

Nowhere is this reversal of priorities more glaringlyobvious than in Piccadilly Circus. Jack Cottonscompany, City Centre Properties Ltd., and the Legaland General Assurance Society Ltd, are investing (theysay) 7 million in redeveloping three quarters of anacre on the Monico site on the north of Piccadilly

Circus. When it was suggested at the Inquiry that theLondon County Council, as the planning authority,should buy 14 acres of land near Piccadilly Circus so asto be able to plan its redevelopment properly, counsel forthe LCC pointed out that the LCCs entire capitalbudget annually for all purposes, including new schools,fire stations, houses, baths, sewage works, roads, parks,old peoples and childrens homes, and town planning,is only 30 million a year, and that to acquire these14 acres would cost 50 million. The LCCs capitalbudget for town planning is only 1,500,000 a year, andof this a mere 500,000 is earmarked for the purchaseand removal of the thousands of factories that are sitedin residential areas (mainly working class) wherethey are the cause of dangerous traffic, noise and airpollution.

These figures suggest two questions. The first is, whyis the LCC so short of capital compared with Mr.Cotton? The second is, why does it cost so much tobuy land or property in central areas?

The first question can be answered shortly. TheLCCs budget is limited, not only by the timidity of theLCC leadership (which envisages no increase in therate of capital investment in the foreseeable future) butalso by the control exercised by the government and thestock exchange. The LCC, like any public authority,cannot borrow a penny without government sanction.

The government not only limits the borrowing of alllocal authorities, but also limits the purposes for whichmoney may be borrowed. It might prove profitable tothe ratepayers if local authorities themselves developedcentral areas, and let shops and offices, or if the localauthorities bought land and collected the profits fromincreasing land values. But they are not allowed, as arule, to borrow for such things. The government,moreover, insists that money must be borrowed athigh rates of interest from the money market, whichguarantees a vast income for the moneylenders, and

13

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

15/78

a fat rake off for the financial houses which organisethe loans. The Stock Exchange regulates the queue ofpublic borrowers that comes seeking loans, rations theamount that each authority can borrow, and so, withthe government, controls the level of capital expenditurefor public purposes. The cost of borrowing is in anycase so high that large-scale public expenditure forcesup the rates: and a Labour authority that borrows toomuch is likely to be ejected by ratepayers who resenthigher rates.

The Building SpreeThe short answer to the second question is that private

ownership of land confers a monopoly, and that in allcentral districts the demand for sites on which largeprofits can be made is concentrated on such a limitedsupply of land, that land values rise very sharply.But this situation, which is normal in capitalist society,has been aggravated by Conservative policy since 1951.A building boom was unleashed by the removal ofbuilding licenses, which had been used by the Labour

government to concentrate building resources on themore essential projects, and by the abolition of thedevelopment charge, which was intended to preventthe landowners pocketing the increase in land valuesarising on redevelopment.

The abolition of the development charge restoredthe free market in land between private buyers andsellers, but public authorities still retained the right tobuy land compulsorily at its existing use value, until the1959 Town and Country Planning Act obliged localauthorities to pay the full market value for land.

But market value is now largely determined (andthis is the strangest perversion of all), by town andcountry planning. If land is zoned under the develop-ment plan as agricultural or green belt land, it cannotnormally be built on and has only agircultural value.But if it is zoned for industrial, commercial or residentialuses, its value is multiplied ten, twenty times or more.By zoning the area of land in which building is allowed,so as to preserve green belts and to prevent buildingsgoing up in the wrong places, town planning whencombined with a free market in land confers immenselyvaluable monopoly rights on the owners of land wheredevelopment is allowed. Moreover, planning authoritiescontrol the density and bulk of building. The morebuilding a developer can put on a site, the more hecan make out of it, and the more valuable the site

becomes. A planning officer, by permitting anotherstorey in an office block, can put 100,000 into thepockets of a developer at the stroke of a pen. Agri-cultural land where building is allowed is known toplanning officers as gold land. The more servicespublic authorities provide at public expense (schools,shopping centres, buses and railways, parks, play-grounds) the more valuable nearby land becomes.Local authorities who buy land for housing or schoolsat market value today are having to buy back landvalues that have been created by their own enterprise.

The public pay for the amenities, but the landownerspocket the profits.

If there is gold to be made near the green belts, thestreets (or the basements) of the city centres are pavedwith diamonds. Evidence was given at the PiccadillyCircus Inquiry by Mr. Dulake, one of the most ex-perienced chartered surveyors in this country, thatthe value of the Monico site acquired by Jack Cottonscompanies was 100 a square foot, or 4,315,000 anacre. He estimated that this site of approximatelythree-quarters of an acre would cost about 3 million,that the building to be erected would cost 1,525,000and that the developed site would be worth 6,944,000giving the developers a profit of 2,419,000, or 50 percent on their capital outlay. Whether these figures pre-cisely correspond with Cottons actual outlay and profitwhich his counsel was desperately anxious to concealfrom public scrutinyis really immaterial. Mr. Dulakesfigures give a true picture of the profitability of develop-ment in central London. It must not be thought that2,419,000 represents the full total of the profits made

from a speculation of this kind. Jack Cotton himselfhad to buy the site from its present owners at marketvalue, and each of them has collected an enormousprofit arising from the sharp increase in land valuesin recent years. Indeed, the real cost of the physicalchanges, clearning the site and erecting a new building,is probably no more than 3 million, so that the totalaccruing to all parties from land values alone wouldbe 4 millionand this on a site no bigger than alargish garden.

Mr. Dulake gave a graphic illustration at the Inquiryof the way in which public expenditure raises landvalues and lines the private purse. The LCCs roadimprovements will enlarge the Circus, and sites whichformerly had frontages on back streets will acquirefrontages on the Circus itself. When the LondonPavilion is demolished, said Mr. Dulake, that site(a site in Great Windmill Street) would front on to theextended Piccadilly Circus, and its value, of course,would be multiplied many, many times. I personallydo not think it is right that the present landowner ofthat particular site should enjoy that kind of increment.And, it might be added, if the LCC ever wants to buythe site referred to, in order to develop the area com-prehensively, it will have to pay a price multipliedmany, many times by its own expenditure in enlargingthe Circus.

The Developers Set The PaceBecause the profits to be made on redevelopment are

so great, it is the developers and not the local planningauthority who set the pace and determine the form ofdevelopment. The cost of urban motorways in CentralLondon was estimated last year by the London RoadsCommittee at over 16 million a mile, two-thirds ofwhich represents the cost of land.

It is insufficiently realised that a revolution is takingplace in the scale of building and town planning.

14

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April

16/78

The city of the future requires completely new archi-tectural forms which cannot be realised on individualbuilding sites. It is the structure and design of the city,or at least of the city precinct, that matters today,because such problems as traffic and pedestrian circula-tion cannot be solved within the confines of a singlebuilding site. If, moreover, modern factory productionand modern building techniques are to be harnessed tothe task of city reconstruction so as to reduce its costand raise its standard, they have to be based on thedevelopment of large areas and a carefully timedprogramme of work. Aesthetically, too, the design ofthe individual building has become of less and less

importance. Even if the Piccadilly Circus building hadbeen a fine example of architecture it was a shockingexample of town design: and a medley of unrelatedbuildings, however well designed in themselves, cannotadd up to a well designed modern city.

In theory the planning authorities possess thenecessary powers to plan the use of land and control thedesign of buildings over wide areas. The 1947 Act enabledplanning authorities to define areas of comprehensivedevelopment, and to designate them for compulsorypurchase. There are many areas where, for obvious

reasons, no large-scale redevelopment is likely for manyyears. But wherever an area is ripe for rebuilding, thedivision of the land between a multiplicity of land-owners and an obsolete road pattern will prevent itsredevelopment for new purposes, to new standards.The alternative is for rebuilding to take place on theold street pattern, perpetuating its congestion, danger,inconvenience and other drawbacks for another 80years or more.

There were two main advantages of defining a com-prehensive development area: the whole area could bemade liable to compulsory purchase, and substantialgrants, up to 90 per cent of their loss, were available

to local authorities. The first advantage remains butnearly all town planning grants were abolished by the1958 Local Government Act, which substituted a blockgrant. This has undermined the financial basis ofcomprehensive planning, particularly when it is com-bined with the severe financial burdens and restrictionsalready mentioned, and the elimination of housingsubsidies for general needs.

All the major successes of British town planningsince the war (and there have been a few, notably atCoventry, in Stepney-Poplar and in the new Barbican

15

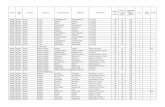

1. This is a model of the advisory scheme for Piccadilly Circus prepared by the Planning Division of the LCC ArchitectsDepartment. It is based on a traffic improvement, to enlarge the Circus in two stages, the first in 1965, the second not until after1972. This scheme attempted to solve the traffic-pedestrian problem by introducing upper level walkways, but its achievement isdependent entirely on the co-operation of the private developers of each site. The first two developers, Jack Cotton on the north

side, and J. Lyons and Co. on the Trocadero site, have rejected the upper level conception.

-

8/12/2019 NLR I2, 1960 March-April