Nicolò Rusca“Hate the error, but love those who err” · church that took place at Tirano and...

Transcript of Nicolò Rusca“Hate the error, but love those who err” · church that took place at Tirano and...

Nicolò Rusca “Hate the error, but love those who err”

Introduction by Pier Carlo della Ferreraand Essays by Alessandro Botta, Claudia di Filippo Bareggi, and Paolo Tognina

[55]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

Nicolò Rusca was born in Bedano, a small vil-lage on the outskirts of Lugano, in April1563. His father, Giovanni Antonio, and hismother, Daria Quadrio, both of whom camefrom distinguished families residing in thearea of Lake Como and the Ticino, sent theirson for his first schooling to DomenicoTarilli, the parish priest of Comano. Afterlearning the basics of grammar and rhetoric,combined with an education that was strong-ly imbued with traditional Catholic princi-ples, Nicolò continued his studies, first atPavia, and then at the Jesuit College in Rome.

After a few months, in 1580, he attended theCollegio Elvetico, founded in Milan byCardinal Carlo Borromeo for the specific pur-pose of instructing and educating in thetenets of orthodox Catholicism young priestsfrom frontier areas that were most exposed tothe spread of Protestantism. Having complet-ed his studies, in the course of which he wasable further to improve his knowledge ofGreek and Hebrew, on 20th October 1586Nicolò Rusca became a deacon and wasordained priest on 23rd May 1587.A few months later he was sent to minister tothe parish of Sessa, a village in the Malcan-tone, west of Lugano, and, two years later,was appointed Archpriest of Sondrio. He wasinstalled in September 1590, having beenduly approved by the municipal council ofthat town and by popular election, ratifiedthe following year by the ecclesiasticalauthorities. He then went to Pavia, to take adoctorate in theology, as required by the

papal regulations of those days.Fr Rusca's first years in Sondrio were markedby his zeal as a priest who was determined toimprove the spiritual and material standardsof the parish of Saints Gervasio and Protasio,where conditions were still fraught with diffi-culty, both because of the rather singularpolitical climate of those days, and because ofthe behaviour of his predecessor, FrancescoCattaneo, which had been open to criticism.

The Archpriest of Sondrio's work in defenceof Catholicism against the spread of what inthose days was called Protestant heresy tookthe form of energetic steps to restore regularobservance of the sacraments (above all con-fession) and the incisive preaching withwhich he upheld the principles of Catholi-cism inherent in the mediation of Christ andthe value of the mass in the public disputa-tions with the followers of the reformedchurch that took place at Tirano and Piurobetween 1595 and 1597. During this period,Fr Rusca promoted the re-founding of theConfraternity of the Blessed Sacrament(1608-1609). As the years went by, the pres-ence of Fr Rusca began to be a thorn in theside of the leaders of the Protestant Leagues(Bünde). Towards the end of 1608, theArchpriest was accused of complicity in theattempt to murder the Protestant preacherScipione Calandrino, a capital offence. Afterfirst surreptitiously taking refuge at Bedano,his birthplace, and then in Como, withBishop Archinti, Fr Rusca returned toSondrio the following year, since the Leaguemagistrates had, in the meantime, ascer-tained his innocence and collected a substan-tial sum of money (representing a fine andthe payment of legal costs) which the peopleof Sondrio volunteered to defray. Thus the priest resumed and intensified hispastoral activities in defence of Catholicism,which developed into strenuous and tena-cious opposition when, at the beginning of1618, the Protestants instituted, at Sondrio, acollege open to the representatives of bothreligions, though essentially under the con-trol of Protestant teachers and preachers.However, Fr Rusca exerted such an influenceover his parishioners that no Catholic attend-ed the college, which, indeed, was never ableto perform its function.This circumstance gave the Leagues and the

Previous page:

Portrait of Don

Nicolò Rusca,

painted in 1852 by the

Sondrio artist Antonio

Caimi (Sondrio,

Collegiate Church

of Saints Gervasio

nd Protasio)

Left:

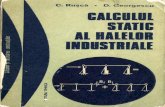

Frontispiece of the

first biography on

Rusca

Nicolai Ruscae S.T.D.

Sundrii in Valle Tellina

Archipresbyteri anno

MDCXVIII Tuscianae in

Rhetia ab Hereticis necati

Vita & Mors – written in

1621 by Giovanni

Battista Bajacca

Above:

The house where

Nicolò Rusca was

born at Bedano in

Canton Ticino

¸ ¸

[56]

Nicolò Rusca

pro-French-Venetian faction – which sawand feared the possible political implic-ations of Fr Rusca's work in support ofAustro-Spanish efforts to gain control of theValtellina – an opportunity to unleash adecisive attack on the Archpriest of Sondrio.According to the descriptions of theCatholic biographers of the day, on thenight of 24th July 1618 sixty armed men,after surrounding the priest's house, burstinto his bedroom, pulled him out of bed and,leaving him barely time to put on his habit,tied him on the back of a mule with his headhanging backwards. The following day hewas taken, via Valmalenco and the MurettoPass, through the Engadine and thence toChur, where he was shut in the attic of ahostelry and kept a prisoner for almost amonth, before being moved to Thusis.There, segregated in a small cell, he wassubjected, at the beginning of September, toa summary trial, accompanied by brutal tor-tures, which his accusers used to get him to

confess to crimes he had probably never com-mitted. But "resolutely and fearlessly, with-out any hesitation", he rejected all accusa-tions as being false and baseless. Exhaustedby the brutality and violence of his ill-treat-ment, which his delicate health could notstand up to, Nicolò Rusca died on 4thSeptember 1618.The day after his death, the Archpriest ofSondrio was already being venerated as asaint and his mortal remains immediatelybecame the object of devotion for Catholics.In the summer of 1619, Fr Rusca's remainswere exhumed by night and taken secretly tothe Abbey of Pfäfers, north of Chur, wherethey remained until half-way through the

19th century. When the Abbey was abolished,the relics were placed in the library, wherethey lay forgotten until 1845, when, thanksto the intercession of the Bishop of Como,Monsignor Carlo Romanò, and the Canon ofSondrio, Giacinto Falcinelli, authorizationwas given for them to be transferred to theValtellina, to the Sanctuary of Sassella.Meanwhile the Bishop of Como himself sentthe following request to the Vatican: "To theglory of God, in veneration of the Priest whogave his soul for his flock, for their good,therefore, and to support the dedicated workof excellent parish priests in my large and dif-ficult diocese, as well as to console me, Iearnestly ask that the relics be solemnly car-ried to the Archpriest's church in Sondrioand placed in a niche, there to be exposedwith lighted candles and revered, especiallyon the day of his martyrdom, as has beendone since time immemorial, in the placewhere they used to lie". Upon receipt of anaffirmative answer, on 8th August 1852,Nicolò Rusca's remains were solemnly borneto the Collegiate Church of Sondrio andplaced at the beginning of the nave, to theright of the main door, where they remain tothis day.At a time of violence, often perpetrated ruth-lessly and with savagery by both the opposingfactions, Fr Rusca stands out essentially as aman of peace. His reasonableness and moder-ation, for all his firmness and convictions, area striking contrast to the excesses of funda-mentalist and intransigent radicalism, ofwhich the court that condemned him is anobvious example. If we are to believe thewords of Bajacca, Fr Rusca's first biographer,whose writings are nowadays endorsed evenby Protestants, the Archpriest of Sondrio"strongly disapproved of all those extremeand injurious utterances that, while theymight do no more than cause bitterness andoffence to heretics, in no way contributed totheir spiritual welfare".

Intent upon winning back the faithful toCatholicism, and not on persecuting or elim-inating those who had embraced the newreligion, he succeeded in enlisting the good-will of all people. A priest who was a goodshepherd, he strove to encourage civilizedattitudes and behaviour, to promote moraldiscipline; the faith he conceived and sup-

The mule-track

leading to the

Muretto Pass,

in the upper

Valmalenco.

Fr Rusca passed

through here,

on 26th July 1618,

on his way to prison

at Chur and Thusis

[57]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

ported he conveyed in words, by preaching,hearing confession, teaching the catechism,and stressing the importance of the word inreligious practice; his attitude to the newreligion was not that of the counter-reform-ing firebrand, but of a peaceful Catholicreformer.

"Hate the error, but love those who err"is a principle traditionally ascribed to theArchpriest of Sondrio Nicolò Rusca: for inhim, faith and Catholic confidence in thetruth that combats and hates error mani-fested themselves in open-mindedness andthe willingness to enter into dialogue of aman who truly loved those who err.

16th-century

picture of Pfäfers

Abbey, where

Fr Rusca's mortal

remains were kept from

1619 to 1845

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

The territory of the Free State of the Three Leagues in the second decade of the 17th century.

The map is from Nuova descrizione della Rezia Alpina Federata e delle terre ad essa suddite, published in 1618 by Filippo Cluverio and Fortunat Sprecher von Bernegg

Politics, Religion, and Society in the Valtellina under

the First Grisons Government

[60]

Nicolò Rusca

[60]

As we know, in 1512, the Valtellina and theCounties of Bormio and Chiavenna wereincorporated in the Free State of the ThreeLeagues, a somewhat singular political grou-ping that had its origin in various pacts towhich the three swore allegiance. The threeentities were: the League of the House of God,also known in the various languages of thearea as Gotteshausbund, or Chadè; the Greyor Upper League, also called the Grauer orOberer Bund, or the Liga Grischa; and the lastto be formed, the League of the TenJurisdictions or Directorates or Zehnge-richtenbund, the smallest of the three. TheThree Leagues were very different from eachother: indeed, the only thing they had in com-mon was their spiritual dependence on Chur.The Free State consisted of a loosely-knitgroup of Communes that, incidentally, in thepast, had not hesitated to include in theirassociation a number of Italian-speakingAlpine valleys, such as the Poschiavo Valley,which, in 1408, had joined the League of theHouse of God as a member with equal rightsagainst payment of an annual fee. Similarly,from 1512 onwards, a document was to makeits appearance in the Valtellina – the FiveArticles of Ilanz – as to whose authenticitythere is some disagreement and whereby, so itwas said, the Leagues agreed that theValtellina and the aforementioned Countiesshould join them as confederate members. According to this agreement, the Valtellinawould be fully entitled to take part on equalterms in the Leagues' Diet, while, however,keeping their autonomy on local matters inexchange for their allegiance to the Leaguesand an annual fee of a thousand florins. Falseor authentic, these articles nevertheless offera clear explanation for the attitude of resent-ment of the people of the Valtellina towardswhat they regarded as their "subject status".This state of affairs was very soon felt to behumiliating, among other things because thearticles of incorporation of what was to beco-me known as the Free State of the ThreeLeagues, or Three Grey Leagues – in German"Drei Graue Bünde" – were drawn up subse-quently, between 1524 and 1526. Thus,between these dates, there was born a federa-tion of federations that had some very intere-sting features, based on the principle of suf-frage, which spread from the local assembliesof neighbourhoods, rural communities that

were theoretically "free", right up to thehighest levels of authority. The neigh-bourhoods were, moreover, amalgamated toform so-called juris-dictional Communes orGrand Communes, about fifty in number, intheir turn grouped into districts, and thenceinto Leagues. In 1524, however, a "central" system of assem-blies was formed, whose will was expressed bya Diet and a body consisting of three LeagueHeads, who generally met three times a year atChur. Much advertised because of their "popu-lar" structure, and very soon praised as beingthe purest embodiment of "evangelical demo-cracy" – but also much contested for preciselythose reasons – the Leagues were in actual facta transitory political system masking diversesocial forces. From the very outset an unnatu-ral alliance of feudal noblemen – both lay andecclesiastical – and of rural communes, theFree State was to experience a powerful trendin the direction of autocratic government by aruling class all too skilled at penetrating com-munal bodies and making them operate totheir own advantage1.How were the subject territories governed? Inprinciple, the Leagues were anxious to con-serve, in the Valtellina and the Counties, thestructures that had grown up when the areawas governed by Milan. All previous autono-mies were therefore protected and thisapplied especially to the old "border" districtssuch as Livigno, Bormio, Chiavenna, and theSan Giacomo Valley. The situation was farmore complex in the Valtellina proper, whichwas kept under tight control. The subdivisionof the territory remained virtually identical towhat it had been during the Milanese domi-nation: the Terzieri therefore survived.Thewhole valley was represented by a Council,whose most delicate task was that of apportio-ning expenses and special taxes, though thesein any case were in the Valley's general inte-rest. In this case, too, the decisions taken hadto be approved by the local communities,

1For these political and institutional aspects, the reader is

referred to my Frontiere religiose della Lombardia. Il rinnova-

mento cattolico nella zona 'ticinese' e 'retica' fra Cinque e

Seicento; Milano, Unicopli, 1999, and to the specific bibliography

it contains. It is also worth mentioning the excellent introduction

by Diego ZOIA; Li Magnifici Signori delle Tre Eccelse Leghe.

Statuti ed Ordinamenti di Valtellina nel periodo grigionese;

Sondrio, L'officina del libro, 1997.

[61]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

[61]

whose existence was regulated by statutesdrawn up in Latin, in 1531, revised in 1538,and translated into the vernacular in 1548;they were finally published in 1549 atPoschiavo.Each community managed the many aspectsof local life, in accordance with habits andcustoms that had mostly been handed downby word of mouth and went back centuries.

This complex structure was supervised by anumber of League officials who resided inSondrio and in the Terzieri: their duties werevenal; in other words, they were rights thathad to be bought, and venality and corruptionwere connected with them, but also the inef-ficiency this engendered which became the"classic" accusation levelled by the bailiwicksagainst the Leagues' rulers. Underlying suchaccusations was the complex problem of thepolitical and social relationships betweenthose ruled – to be precise, the lords of theValtellina, who were certainly far less power-ful than those of the Plain of Lombardy pro-per, yet sufficiently strong and united to standup for their economic and, above all, politicalrights over their territory – and the greatfamilies of the Leagues, who came from areasthat, when all was said and done, were poorand therefore had a vested interest in the pro-sperous Italian-speaking valleys. Thus theValtellina was destined to be the main bone ofcontention, if only because it was the richestarea and the Leagues would continue toregard it as economically indispensable anddefend it tooth and nail.To this atmosphere of tension must be added

a further cause of friction, which was destinedto become more acute: religious differences2.Having become League territory before theReformation broke out, the Valtellina and theCounties were soon to find out that they hadto reckon with a State in which the ideas ofZwingli had spread like wildfire: this was alsodue to the fact that the Rhaetian Communeswere autonomous and there was no central

government to impose its will. In a situation in which the Bishop of Chur, asthe feudal overlord, was still extremely power-ful, the Articles of Ilanz in 1524 were above allto revolutionize the part played by church-men, henceforth to be under the control ofthe civil authorities: thus, judicial rights werecircumscribed, ecclesiastical bequests wereregulated, and the principle was establishedwhereby the secular clergy were to be directlyelected by parishioners' assemblies.Subsequently, in June 1526, an attack waslaunched, first and foremost, against theauthority of the Bishop of Chur.Vacant livings, which were generally in thegift of the Pope, were now only to be givento local inhabitants, all endowments andrights to tithes were readjusted, and strictlimitations were set on the expansion of theproperty of the clergy, on the freedom tomake wills in favour of ecclesiastical bodiesand clerics, and even on the admission ofnovices to convents: these were decisionsthat, in principle, should also have applied

2 See also my studies, especially regarding the case in point of the

Valmalenco, and the aforementioned bibliography.

Chur at the beginning

of the 17th century,

as shown in the

Descrizione della Rezia

by Johann Guler von

Weineck (1616)

[62]

Nicolò Rusca

to the bailiwicks, which was to happen muchlater, when new Statutes were published.Moreover, the Leagues determined to act inthe only way that would make it possible toavoid the final break-up of the fragile, newly-born Free State. This was to be achieved byassigning the ius reformandi to the indivi-dual communities, at the same time recogniz-ing the equal status –the first time this hadbeen done in Europe at that time – of theCatholic and Reformed religions, with theexplicit exclusion of any extremist sects – alaw that was of course applied, immediately,to the Valtellina and the Counties. At thispoint it is above all worth reflecting on thefact that the application of this law to theValtellina and the Counties, which the Valleys

considered unduly harsh, represented the extension - which it could hardly be said wasnot legitimate - of laws enacted by theLeagues in respect of the territories regardedby them as to all intents and purposes"subject". However, it soon became clear thatthe Leagues, inevitably, aimed not only toprotect freedom of worship for the minor-ities, but also to implement a policy thatwould in various ways favour the spread inthe Valleys of the Reformed Church. It was acourse of action that was to some extent alsomade necessary by the special nature of theareas concerned, which were subordinate to aspiritual authority, that of the Bishop ofComo, located outside the confines of theState and therefore beyond any control – forone thing, because they were part of an impe-rial state (as Milan itself was to be after thedeath of the last Duke): that of Spain, andtherefore hostile. Thus, while the Protestantcommunities of the Three Leagues were busyorganizing themselves throughout their

State, when, at the beginning of the 1640s,the initial doctrinal rigidity of the Catholicsproduced a wave of religious exiles, many ofthem settled in the Valleys, which were lin-guistically Italian and tolerant on religiousmatters. The Leagues, being unaware of thereligious anxiety of these exiles, allowedthem to settle almost immediately, givingthem a position of privilege: indeed, it wasthey who set in motion in the area new doc-trines that, while they took root among verysmall groups, nevertheless became extremelywidespread throughout the territory. It is generally held that the Reformationappealed not so much to the aristocracy –very few of whom were attracted to it – nor tohumble folk, who retained their loyalty to theold faith, but to an intermediate class thatwas both educated and moneyed, consistingof merchants, but also notaries and perhapschurchmen too, for whom probably the set-ting up of links with the newcomers meant,as in the case of the Valmalenco, significantfinancial and perhaps political opportunities.From the religious angle, therefore, theaction taken by the leagues was perfectlyunderstandable, albeit clumsily executed.Indeed, the aversion of the nobility, who hadbeen driven out of local government, addedto which, naturally, there was the antipathyof the clergy in the Valleys, meant that pro-spects of expansion for the new church wereextremely limited. Yet, precisely for that rea-son, the Leagues attempted to protect thesmall Protestant communities and to enablethem to settle permanently. In 1557, the Diet of Ilanz accorded theProtestant pastors – who, incidentally, werealso carefully watched – the freedom to preachand, at the same time, took steps that weredestined to become very unpopular. Forwhere there were at least three Protestants,this meant that a community had been legi-timately constituted; according to the law,the Catholics must therefore give them achurch – where there was more than one –or, allow them to share the one and onlychurch, using it alternately; likewise, ceme-teries were to be available to both religiouscommunities. Moreover, the following year,the Diet of Davos laid it down that everypreacher should be guaranteed an annualsalary, to be paid for by drawing on the in-come of the local churches, or of the com-

View of Sondrio

between the 17th

and 18th centuries

(Sondrio, Valtellina

Museum of History

and Art)

[63]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

mune, should the former prove inadequate.As was to be foreseen, these regulations led toendless disputes and local vendettas, espe-cially when there were very few Protestants:as once again, in the case of the Valmalenco,this happened whenever the interests of com-munities, which were mostly poor, wereinvolved, for they immediately consideredthemselves treated unfairly, if only because asubstantial part of the local ecclesiasticalendowments had probably been placed at thedisposal of individual Protestants, or at anyrate of their families.On the other hand, this provided the Catholicclergy with an excellent excuse to complain,for, understandably, they felt themselveshemmed in on all sides. Their main preoccu-pation was the plan pursued by the Leagueswith great insistence until 1620, to sever allties with the Bishop of Como, a link that hadbegun to cause anxiety half-way through the16th century because of the Counter-refor-mation that the Catholics had set in motionat the Council of Trent, which at that timewas drawing towards its conclusion. The factthat the Bishop of Como had always felt him-self threatened by the Leagues was nothingnew, for they were largely Protestant. In addi-tion, as we have said, they had no centralgovernment: any decision to be taken for thewhole State involved laboriously securingmajorities among the communes, one byone- which was normally done with money.On the other hand, the conclusion of theCouncil of Trent only increased the concernof the League leaders, for now the Church ofRome was again energetically pursuing apolicy of expansion. In 1576, a decree was issued by the Leaguesforbidding any foreign churchmen to enterthe Valleys, including the Bishop of Como,whose task it was to reorganize the basicstructure of the local churches, which wereoften beset by errors and shortcomings, inapplication of the decrees of the Council ofTrent, according to both the spirit and theletter. The following year, an edict even threa-tened with imprisonment, or other moresevere penalties, anyone, whether an indivi-dual or a community, who offered hospitalityor in any way helped foreign clerics ormonks. All these measures were aimed at thevery heart of the Church of the Counter-reformation, which found itself prevented

from doing everything it regarded as mostcritical and vital: the cultural, pastoral, andmoral reform of its clergy was a prerequisitenot only for building a moral Christiansociety, but also a sine qua non for haltingthe spread of the Reformation, which, it wassaid, had been born of the "evils" of theChurch. It is therefore easy to understandwhy most of the steps that CardinalArchbishop Carlo Borromeo in Milan waspreparing to take to help the Catholics in theFree State of the Three Leagues involvedvisiting that area; permission to do thishowever, was always to be denied, untilBishop Ninguarda of Como managed to pay avisit in 1589, since, being from the Valtellinahimself, he could not be prevented fromentering the Valleys. Nor were outsiders bar-red merely from entering, but from leavingtoo, for in 1618, the Governor of Sondrio wasstill forbidding clergymen from the Valtellina,"on pain of a fine of a thousand scudi", toattend the last synod in Como convened byBishop Filippo Archinti: a prohibition,obviously, to be taken seriously, since nopriest dared go to Como. True, it had becomea common practice for priests, generallymembers of orders, to be despatched to theValtellina in disguise. Nevertheless, even theofficial visit paid in 1589 by BishopNinguarda, who, as we have said, since hecame from the Valtellina, could not legally bekept out, was a very hurried one, aimed aboveall at renewing contacts that had been inter-rupted for too long and estimating the dama-ge caused by the Protestants – in otherwords, little more than a rapid survey of thesituation. The first real visit was that paid byBishop Filippo Archinti in 1614-15, after hehad obtained authorization from the Leagueleaders to enter the Valtellina. Permissionwas granted in return for a considerable sumof money and at a most inconvenient time ofyear: the winter. The Bishop was then per-suaded to shorten his stay, which thereforebecame little more than a careful census ofthe churches and parish assets, about whichthere were many complaints due to the factthat the Protestants had been entitled to liveoff the parishes since 1557. Only with theterm of office of Bishop Carafino, who was incharge of the Diocese of Como between 1626and 1665, do we finally get the impression ofthe Valleys functioning in accordance with

[64]

Nicolò Rusca

the principles of the Council of Trent.With regard to Christian doctrine and theeducation of the laity, Bishop Archinti's visitwas highly significant, because the Diocese ofComo was situated on the border betweentwo religions. Hardly any concrete informa-tion transpired, however, from his visit. Onlyat Sondrio does Fr Rusca appear to haveorganized things, for he reports on how thiswas done: "After ringing the big bell a secondtime and calling the boys and girls together,we make them say their prayers a few times.The boys are taught by the priests and othermen; the girls, by women, especially theschool teachers. They are then made to takepart in discussions, the boys being made tostand on pulpits made for the purpose; thegirls assemble below. After that, if there istime, they will sing first the Paternoster, thenthe Ave Maria, then the Credo, and so on.Lastly, comes a song of praise, sung kneeling;the first verse is sung by the clergy and theboys together, the second by the girls andwomen together, and so on; at the end,Vespers are sung. But it is difficult to getthem interested in Christian doctrine, espe-cially the boys, who are likely to run away andhide so as not to be found by anyone lookingfor them"3. Even though the case of Sondriowas rather special, Fr Rusca emphasized heresome typical, yet striking points. Above all,we find the customary separation of boysfrom girls. The education of the former washandled entirely by the priests. The girlswere, as usual, taught by a few "women". Weknow, incidentally, that at Sondrio, therewere actually six school mistresses, who alsodealt with the teaching of the catechism:moreover, it is probable that, as in the ThreeValleys, difficulties were overcome thanks tothe presence of schoolmasters who werecapable of inculcating the rudiments of thefaith. This is what still happened, for exam-ple, at Poschiavo, another area of tensionfrom the religious point of view where, in1611, Cardinal Federico Borromeo "to meetthe urgent need of the Catholic communityat Poschiavo for masters to teach the chil-dren, so as not to expose them to the risk ofattending schools run by heretics", decided topay for a master himself "with orders toattend to the teaching of the boys and youngmen, to meet the need of the village for ourholy Catholic faith, and for Christian

customs and letters4". However, one has theclear impression that Fr Rusca interpretedthis doctrine in accordance with his ownhighly personal style, preferring discussionto the mere teaching of the catechism: suchis probably the meaning of the children'sbeing made to "discuss" – in other words, tostand up in public – which, for the boys,actually meant using a sort of "pulpit". It isworth noting that the report on BishopArchinti's visit also contains a list of the"compositions of the Archpriest of Sondrio",most of them argumentative.But the case of Sondrio appears to be anexception, and perhaps that is why it has beenhanded down to us in such detail. Thus,generally speaking, the account of theBishop's visit says practically nothing aboutteaching the catechism, of whose importan-ce, as we have seen, he was well aware, andthis was perhaps because his mind was stilllargely taken up with checking on the clergyand their training. The obligatory catechismclass on Sundays was certainly always stres-sed in instructions, but practically nothinghas been handed down to us on this subject,although that does not necessarily mean thatthe teaching of the catechism was neglected.On the contrary, no serious objection was rai-sed by the local authorities to the conduct ofthe religious life of the Catholic communitiesas regards preaching and the teaching ofChristian doctrine, as long as no proselytism– an attitude that was expressly prohibited bythe Leagues' two-denominational regime –was practised.However, as regards the area of Chiavenna,we know of an edict dated 1597 on thesubject of the teaching of the catechism inthe Catholic community. This was a procla-mation by the League's representative atChiavenna that laid down "the obligation ofpriests to have the Paternoster, the Credo,and the Ten Commandments said in the ver-nacular". This requirement probably revealssome anxiety lest the teaching of the catechi-sm be conducted differently as betweenCatholics and Protestants: "Whereas… it isthe common wish of our most illustrious and

3 Filippo ARCHINTI; Visita pastorale alle diocesiI, partial edition; in

"Archivio Storico della Diocesi di Como", vol. 6, p. 521; Como, 1995.

4 Filippo ARCHINTI, cit., p. 374.

[65]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

excellent lordships… that in the country oftheir subjects, and especially in places wherethe prayers mentioned below are not taughtby priests and friars to their flocks in this way– that is, the Our Father, the Creed, and theTen Commandments – be by one and allobserved when conducting their sermonsand masses; and, moreover, recited aloud inthe vernacular and intelligibly, so that everyperson may understand them and profit the-reby, and live in a Christian way and in accor-dance with the pure and sacred word of God,without either adding to or abridging anypoint, this being for the benefit of all, espe-cially the unfortunate and ignorant… whe-refore… this public cry, ban and command-ment is issued, that each and every priest,friar, or curate,… be willed and obliged,upon pain of being expelled from their office,or even banished from the domain of hismost excellent lordship… in all their ser-mons, masses, and other services celebratedby them, whether in public or privily, to say,recite, or teach the aforementioned prayers,

written below, the Creed and the Ten Commandments, being the sum total of thelaw, in the aforementioned manner, as fol-lows… First, the prayer that our Lord JesusChrist spoke… that is, the "Our Father"…followed by the statement of our faith, as doall Christians, which, commonly referred toas being the symbol of the apostles…That is: 'I believe… ' '…followed by the Ten

Commandments of the Laws of God, whichare written in Exodus, Chapter 20 ….'". Thecry ended, in the Protestant manner, withanother brief reference to the scriptures:"The sum total of the whole law is this. Thoushalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart,and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind,and with all thy strength. Though shalt lovethy neighbour as thyself. On these two com-mandments all the laws and the prophetsdepend. St. Mark, Chapter 12"5.The ban thus illustrated most eloquently theconcern of the Leagues' leaders about theteaching of the Catholic catechism materiali-zing at that time, which was different fromProtestant teaching: neither precepts of thechurch, therefore, nor training in the discus-sion of controversial subjects was considered.The aim, leaving aside any differences of adenominational nature, was thus to findcommon ground in the area of upbringing,or rather the education, both religious andsecular, typical of the "good subject": expres-sed in a sober lifestyle, moral rectitude, use ofthe vernacular, and with ideas reflected in thescriptures alone: "to live in a Christian wayand in accordance with the pure and sacredwords of God, without adding to or abridgingany point". As regards preaching, often a sub-stitute for doctrinal education, the "faithfulsubjects of the County of Chiavenna of theCatholic religion" were allowed "according totheir need, to accept, take, or provide them-selves with preachers, upon condition, howe-ver, that… they be natives of the land ruledby their lordships of the Leagues and theirsubjects, or else Swiss, and that such prea-chers pronounce or say, in the Italian verna-cular, before the people, the ordinary prayersof their church according to their religion".From the point of view that concerns us here,we are bound to feel that, on the whole, theimportance that the Protestant communitiesgave, both to preaching and to instruction inthe catechism, were a convincing example forthe Catholics too: for the same bell was, forinstance, used to call the faithful of both reli-gions to listen to a sermon or to their doctri-ne. For Catholics, the training of the clergyremained fraught with difficulty: nor was it acoincidence that Bishops Archinti andCarafino both devoted much attention to this

The religious wars in

the Valtellina culmi-

nated in the summer

of 1620 in a massacre

of Protestants.

At the Battle of Tirano

on 11th September the

Valtellina forces repulsed

a League counter-attack

(copper low-relief by

Renzo Antamati, 1950)5 Filippo ARCHINTI, cit., p. 659-661.

[66]

Nicolò Rusca

matter. Now, most of the Valtellina priestsbetween the end of the 16th century and thebeginning of the 17th do not appear to havebeen particularly brilliant from the point ofview of their education, and many parishpriests seem to have studied only "human let-ters" or "grammar"; nevertheless, despite thecriticism levelled at this situation, we find nocases of glaring abnormality. A little less thanone third of the clergy consisted of theolo-

gians, numbering 45 out of 126, 17 of whom had studied at the Collegio Elvetico, whichsince 1579 had been the only practical, con-structive step taken to help the Valtellina andthe Counties: for out of a total of 38 students– though this number varied over the years –only 6 places were reserved for the "GreyLeagues" and 8 for the Valtellina. Moreover, itis worthy of note that, in the areas wherethere was most political tension, specialattention was given to the training of priests:at Sondrio, as we have seen, there was FrRusca, but in the Valmalenco 2 out of 3 of thelocal priests had studied in Milan; at Villa diTirano and Mazzo, there were 8 theologiansin all, 3 of whom had studied at the CollegioElvetico; at Tresivio, there were 3 out of 7;while, in the Valchiavenna, 5 out of 9 theolo-gians came from the Elvetico and 2 from theCollegio Germanico in Rome. We can there-fore see, in retrospect, that the challenge ofwhich both the Borromeo cardinals and theBishops of Como were aware was, above all,that of the re-education of the clergy inaccordance with the rules of the new Churchthat had emerged from the Council of Trent– and this explains the many gaps in ourinformation regarding care of the laity rightup to the end of the 17th century. A salientfactor is that, as the new century approached,

all denominations were closing their ranksand standing four-square in defence of theircommunity in a situation fraught with ten-sion, including pressure from outside thecountry: from the disputes regarding the pay-ment of tithes to the disturbances connectedwith the Johann von Planta affair, all issuesfell within the framework of the Night ofSaint-Barthélmy massacre of the Hugue-nots6. And if the key to an understanding of16th-century Catholicism turns entirely onthe implementation of the decisions of theCouncil of Trent, the events that marked theend of the 16th century in the area ruled bythe Leagues have to be understood within theframework of the complex and convulsivepolitical activities going on there – for, withinthat institutionally extremely weak, indeedalmost non-existent structure there seethed,and continued to seethe in practice to thevery end, the unsolved problem of striking apolitical balance between the "aristocratic"component of the Free State and its "popular"core. As the historian, Randolph Head, hasvery clearly shown, political and social deve-lopments in the area, since half-way throughthe 16th century, had been moving decisivelytowards a strengthening of the local positionof a number of families – especially the vonPlantas and the von Salis – who had found avirtually inexhaustible source of wealth inmilitary careers, in their estates, and inbanking – closely connected activities – aswell as in official positions in the communes,in the main offices of the Leagues, and ofcourse in the bailiwicks – but above all in thepensions and donations received from theforeign powers, for whom these were a meansof bringing political influence to bear, bothinternally and externally, on the Leagues. Thus two opposing fronts were created: the

The bull with which

Pope Gregory XIII

ordered the founda-

tion of the Collegio

Elvetico in Milan,

where Fr Rusca

completed his studies

(original in the Milan

Archiepiscopal Archives)

6 On these subjects, the reader is referred to La Valtellina crocevia

dell'Europa. Politica e religione nell'età della guerra dei

Trent'anni, edited by Agostino BORROMEO, Milano, Giorgio

Mondadori, 1998, which nevertheless, in substance, revives the

old politic–diplomatic–military approach to the subject. Far more

recent is the study by Randolph C. Head, Early Modern democra-

cy in the Grisons. Social Order and Political Language in a Swiss

Mountain Canton, 1470-1620 Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press, 1995, which, however, the previous text does not even men-

tion. Next it will be worth also consulting the manual of the his-

tory of the Grisons, Handbuch der Bünder Geschichte. Frühe

Neuzeit; Chur, 2000.

[67]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

great families, on the one hand, and the com-munities on the other, whose ancient rights ended by being defended by the younger gene-ration of Protestant pastors, who resorted toarmed insurrection and special courts as wea-pons against the governing elite, made up of asmall number of those same patrician families. The violent history of the Leagues, as well asthat of the Valtellina in the 17th century may beseen as beginning with the unresolved conflictbetween the Communes and the dynasties. TheCommunes had very few arms at their disposalto help them to put up a resistance: ancientpacts and the traditional structures of the peo-ple and, last but not least, the resort to "demo-cracy", which the Protestants claimed as theirvery own. This process was strongly supportedby the Protestant church – many proposals tothis effect were to be advanced by Protestantministers of religion – and in any case it founda sympathetic echo in the Protestant Cantons ofthe Swiss Confederation, thus forming a sort ofunited "Protestant front". Such therefore is thecontext in which we have to view the eventssurrounding the Sondrio school and the gra-dual deterioration of an inter-denominationalmodus vivendi that, without ever having runtoo smoothly, had nevertheless lasted for sometime. When international politics eventually setits sights on League territory, assigning to it animportant position on the European chess-board, at the beginning of the 17th century, theresult was to be years of chaos and hardshipduring which the Leagues, but a step away from

civil war, would be risking total disintegration.Up to 1622, continual resort was had to the"Fähnlilupfe" – translated literally "raising offlags" – which were armed insurrections inwhich the Communes played a considerablepart; they were a sort of endless spiral, sinceevery peasant uprising ended in the setting upof a special court, whose activities consistedmainly in meteing out punishment, led to theorganizing of further Fähnlilupfe, in a crescen-do that reached its climax with the famousStrafgericht of Thusis in 1618, which hadoriginated in disturbances centered inEngadine, at Zuoz, that were directed againstCatholic leaders in the Valtellina and led byProtestant pastors and the heads of theVenetian faction. The insurgents marched toChur and thence to Thusis, where eventuallyabout 2000 men assembled. A court of sixty-sixjurors was elected, though this time – and thiswas a complete novelty – the Criminal Courtwas supervised by nine young pastors repre-senting the most radical wing of the synod ofLeague pastors, who were the very incarnationof the will to defend the autonomy of theCommunes. The Court proceeded to take harshaction against the enemies of the Venetianparty, and therefore against the von Plantas, aswell as against the chief representatives of theValtellina clergy, who included Fr Rusca. Thusthe trial of the Archpriest of Sondrio occupies aplace in the complex political situation buildingup around him, in which the pressure exertedby the great European powers on the impotentFree State of the Three Leagues was very great.Thus it was caught between the attempt by theinternational Calvinism to unleash an unprece-dented attack on the very heart of the Empireand the ferocious reaction to this of the armiesof the two Habsburg monarchies, which, afterthe complete defeat of the Bohemians in 1620,led to the hereditary throne of Bohemia beingceded to the Habsburgs, but was also to sparkoff a series of chain reactions that transformedwhat had been an internal strife within theEmpire into a long and terrible continental warin which the Valtellina became the southernfront of a contest that was being fought outelsewhere.

Claudia di Filippo Bareggi

Associate Professor of Modern History at MilanState University

The portrait of

Nicolò Rusca in the

Town Hall of

Bedano.

Painted a few years

after the priest's death,

the picture belonged to

the Rusca family and

was donated to the

Ticino municipality

about half-way through

the 19th century

A page from the minutes of the Criminal Court of Thusis in 1618

(the original is kept in the Grisons State Archives in Chur)

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

The Criminal Court of Thusis (1618) and the Death of Nicolò Rusca

[70]

Nicolò Rusca

The year 1618 was marked by two indirectlyconnected events that had negative conse-quences for the future of the Free State ofthe Three Leagues: the failure to institute aLatin School at Sondrio, and the setting upof a criminal court at Thusis.The Sondrio school plan had already beendiscussed by the synod of pastors in 1596. Ithad been their intention to proceed with anexisting scheme that had broken down in1584 due to the pressure exerted by CardinalCarlo Borromeo and the Catholic cantonson the government of the Leagues and theopposition of the Archpriest of Sondrio,Gian Giacomo Pusterla. The second attempt to open a Latin schoolin the Valtellina was likewise a failure. At atime of growing discord and rumours of war,when it would have been better to promotesteps that would have reduced tension, theplan to set up the school at Sondrio turnedout to be a grave error. Indeed, once again,it resulted in conflict with the Archpriest ofSondrio – Pusterla's successor, Nicolò Rusca– who was irritated at the fact that three ofthe five teachers (including the principal,Caspar Alexius) were Protestants. Thefinancing of the school also proved to be acause of friction, inasmuch as the inhabi-tants of the bailiwicks had no intention ofcontributing. In the Valtellina, opposition tothe Sondrio school was further intensifiedby the fact that, at that time, the Leagueshad forbidden the Jesuits to open a school atBormio – not that the authorities in theLeagues were the only ones to oppose Jesuitschools: suffice it to remember the closureof the Jesuit college at Roveredo ordained byCardinal Carlo Borromeo in 1583.

In fact, at the Diet of Davos in August 1617,a number of members pointed out that itwas inadvisable to pursue a line thatappeared to allow some to do things thatothers were forbidden to do; but their argu-ments did not convince the majority:indeed, they incited the extremists todemand that the Latin school in theValtellina be opened at any cost. Moreover,the tension that had built up in theValtellina on the subject of the school fur-ther aggravated the bitterness of the conflictbetween opposing factions within theLeagues7.

Nor was the Synod of the Pastors of theLeagues immune to the differences betweenthe factions, as is proved by the proceedingsof the Synod of Bergün in spring 1618, whena determined minority of young extremistpastors, who regarded with suspicion anypersons who felt any sympathy for theSpaniards, regarding them as the enemies ofthe religious and political freedom of theLeagues, took control of the meeting. Thechairmanship of the synod, which was theprerogative of the pastor of Chur, GeorgSaluz, a moderate who was against anyinter-faction strife, not automatically preju-diced against the pro-Spanish faction, andsevere in his condemnation of the ideologi-cal radicalization under way among some ofthe Rhaetian pastors, went to the pastorCaspar Alexius, principal of the Sondrioschool. The Synod of Bergün attempted toexpel from among its ranks any pastors sus-pected of "Hispanism" and circulated a let-ter, which was read in all the Leagues'churches, that urged everyone to beware ofpeople with pro-Spanish sentiments, toexpose their machinations and denouncetheir plots. Ordinary citizens were warnedto be on their guard against anyone receiv-ing a pension from a foreign power, thusposing a threat to the freedom of theLeagues. The letter concluded by urgingthat all this action should be conducted dis-creetly and without the use of arms8.

This call, which had the effect of furtherstirring up feelings, went out during a peri-od characterized by inflamed political andreligious controversy and by frequentclashes between the factions, enlivened byarguments as to whether a treaty of allianceshould be signed with Spain, or whether theone recently concluded with Venice, butwhich had just expired, should be renewed.

7 Silvio FÄRBER has devoted a number of illuminated pages to

the subject of the factions present in the Leagues at the beginning

of the 17th century in his essay Politische Kräfte und Ereignisse

im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, in: Handbuch der Bündner

Geschichte. Frühe Neuzeit; Chur, 2000, pp. 118-131.

8 This letter is partly reproduced in: Petrus Domenicus ROSIUS À

PORTA; Historia Reformationis ecclesiarum Raeticarum ex genui-

nis fontibus et adhuc maximam partem numquam impressis sine

partium studio deducta. II; Chur, 1777, p. 258.

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

Demonstrations, to which speeches made bya number of pastors also contributed, brokeout in the Lower Engadine against thenobleman and judge Rudolf Planta ofZernez, who was accused of being pro-Spanish and of having threatened to with-draw to the Valtellina in order to organizethere an uprising against the Leagues. Inspite of the attempt to mediate, first by thethree heads of the Leagues, and then by adelegation that included the pastors GeorgSaluz and Stephan Gabriel, the disturbances

did not subside. On the contrary, a criminalcourt was even organized, and it was planned to despatch armed detachments with instructions to arrest members of thePlanta faction in the Valtellina, theBregaglia Valley, and Chiavenna. At Sondrio,the Archpriest Rusca was arrested, togetherwith some others. The town of Chur, whichhad been chosen as the seat of the criminalcourt, refused to open its gates to the citi-zen's brigades. A few days later, the courttransferred itself to Thusis.The declared purpose of the criminal courtwas to act in the name of all the Leagues'citizens in defence of political and religiousfreedom. The 66 judges, sent above all bythe Protestant communes of the League ofGod's House and the League of the TenJurisdictions, included Catholics, albeit notvery many. The whole trial was influencedfrom the very outset by the presence, in asupervisory capacity, of a number of pastors

– at whose participation even Protestants atonce protested vehemently9. Among thosepresent were Stephan Gabriel, a pastor fromIlanz, Jakob Anton Vulpius, a pastor fromFtan, Caspar Alexius, principal of the schoolat Sondrio, Blasius Alexander, a pastor fromTraona, Georg Jenatsch, a pastor fromBerbenno, Bonaventura Toutsch, a pastor atMorbegno, Conrad Buol, a pastor at Davos,Johann à Porta, a pastor from Zizers, andJohann Janett, a pastor from Scharans. Thechroniclers Bartholomäus Anhorn andFortunat von Juvalta produced a criticalanalysis of the parts played by the pastors –especially Johann Janett, Georg Jenatsch,and Caspar Alexius – and became spokes-men whose comments were severelyadverse. Juvalta stated that the pastors werein charge of proceedings and of the exami-nation of evidence, and that the proceedingsof the court was in their hands. The pastors,however, had not been allowed to vote whenthe time came to decide on the sentences tobe passed on the accused.In a declaration drawn up at Thusis, the pro-moters of the criminal court, presided overby Jakob Joder von Casutt, proclaimed theirintentions to ensure the sovereignty andfreedom of Rhaetia, to eliminate all foreigninterference, to prevent the machinations ofthose citizens of the Leagues who receivedpensions from abroad, to annihilate the pro-Spanish faction, and to compel all subjectsto respect the laws and the members of bothreligions to live together in peace10.Although the Court of Thusis is oftenremembered only for having tortured andkilled Nicolò Rusca, it should not be forgot-ten that it was active for a full six months,from August 1618 to January of the follow-ing year, and that during that time it passed

Don Nicolò Rusca

appears miraculously

to Jürg Jenatsch.

This episode, in a draw-

ing by Otto Baumberger,

was imagined by Conrad

Ferdinand Meyer, the

19th-century author

who wrote the historical

novel Jürg Jenatsch. Eine

Bündnergeschichte.

Jenatsch was one of the

judges of the Criminal

Court of Thusis who

attacked the Archpriest

of Sondrio most

relentlessly

9 Bartholomäus ANHORN; Der Graw-Pünter-Krieg. 1603-1629,

edited by Conradin von MOHR; Chur 1862, pp.32-34;

Fortunat von JUVALTA, Denkwürdigkeiten, 1565-1649, edited by

Conradin von MOHR; Chur 1848, pp. 47-50 and 57-58.

10Andreas WENDLAND, Der Nutzen der Pässe und die Gefährdung

der Seelen. Spanien, Mailand und der Kampf ums Veltlin (1620-

1641); Zürich, 1995; pp. 72-76. As regards the general situation in

the bailiwicks, at the beginning of the 17th century, and relations

between the prince and his subjects: Guglielmo SCARAMELLINI,

I rapporti fra le Tre Leghe, la Valtellina, Chiavenna e Bormio, in:

Storia dei Grigioni, L'età moderna; Bellinzona, 2000, pp. 151-165).

[71]

[72]

Nicolò Rusca

157 sentences against as many accused. Inan initial phase, which lasted nearly twomonths, the court tried the brothers Rudolfand Pompejus Planta, the mayor Giovanni Battista Prevosti, the archpriest Nicolò Rusca, Gian Antonio Gioiero, Lucius deMont, and the Bishop of Chur Johann Flugi. All were citizens of the Leagues and laymen,except for Rusca and Flugi; all wereCatholics, except for Prevosti.

The first man to appear before the judges atThusis was the mayor Giovanni BattistaPrevosti, known as "Zambra", of Vicosoprano in the Bregaglia Valley. He was accused ofhaving been in touch with Milan during theconstruction of the Fuentes fort, of havingspread false information regarding theintentions that had led the Spaniards to erectsuch a fortification at the entrance to the val-leys of the Adda and the Mera, of havingopposed the idea of attacking the fort, and ofhaving used threatening language againstanti-Spanish pastors. Prevosti, who was relat-ed to the Planta brothers, rejected all accusa-tions and recalled that he had been acquittedin the course of a previous trial. The pastorsadvised him to denounce Rudolf Planta, buthe would not speak. After lengthy tortures –he was "hoisted up" more than 40 times – theseventy-year-old mayor of Vicosoprano madea confession that seriously compromisedhim. On 22nd August 1618, the court con-demned him to death for high treason. Thesentence against the Protestant Prevosti wascarried out immediately. Next it was the turnof Pompejus Planta, the owner of RietbergCastle, in the Domleschg Valley, who hadfled to avoid arrest. Found guilty of hightreason, because of the close links he was

presumed to have with the emperorMaximilian of Austria, he was condemned,in absentia, to permanent exile. The courtalso decreed that all his property should beconfiscated and his house demolished; italso proclaimed that he should immediatelybe put to death if he re-entered the country.On 1st September 1618, the trial began ofthe Archpriest of Sondrio, Nicolò Rusca,who was just over fifty years old, though hishealth was delicate. Before beginning tocross-examine him, the court deprived himof his priestly status. The main charge lev-elled at Fr Rusca was that he had, during theyears before 1590, together with Gian PaoloQuadrio and Vincenzo Gatti, both of theValtellina, planned to eliminate the pastor ofMorbegno, Scipione Calandrino. TheArchpriest's intention was alleged to havebeen to murder the pastor or to have himkidnapped and taken away beyond the con-fines of Rhaetia and thence to Milan orRome. The accusation was based on evi-dence given by Michele Chiappini, of Pontein the Valtellina, in 1612. Rusca rejected thecharge, contesting the truth of Chiappini'sstatement and maintaining that he hadenjoyed friendly relations with Calandrinoand had even exchanged books with himduring the period when he was a pastor atSondrio – to which other charges wereadded in connection with more recentevents.According to some witnesses, the Archpriesthad shown intolerance and a rebellious atti-tude towards the authority of the Leagues;in particular, he was said to have pouredscorn on decrees issued for the purpose ofensuring the peaceful coexistence of the tworeligions. He was said to have told a youngman that those who attended Protestant ser-vices would most certainly end up in hell. Itwas alleged that, according to a number ofletters, Fr Rusca had shown disdain towardsthe decree issued by the Rhaetian Dietagainst preaching by foreign monks insouthern bailiwicks, and that he did notintend to obey such laws. On another occa-sion, displaying insubordination towardsthe authorities, the archpriest was said tohave opposed the setting up of the school atSondrio resolved upon by the Diet of theThree Leagues. Moreover, he was reportedto have stirred up the common people to

Thusis before

it was destroyed

by fire in 1727

[73]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

such an extent that it became difficult forany authorities to take action against him.The list of charges ended by recalling thatthe archpriest had not complied with thesummons to appear before the criminalcourt in Chur, in 1608, and that, on thatoccasion, he had sought to bribe someCatholic members of the court. It was addedthat he continued to have close ties with theenemies of the Leagues, both abroad andwithin the Leagues themselves; that, whenthe Fuentes fort was being built, he wasreported to have been to Morbegno severaltimes to urge Catholics not to lend theirsupport to any armed action against theSpaniards, and that he had held meetings, inSondrio, in the priest's house, in the courseof which strong language had been usedagainst the Rhaetian authorities.The archpriest rejected all charges, declaredhimself a loyal subject of the Rhaetianauthorities, implored the pastors not to tor-ture him, and said that he would rather beexiled or sentenced to hard labour. Thejudges ordered that cross-questioningshould continue and that torture should beused. The prisoner died, on the second dayof torture, without having confessed any-thing. The court ordered that all his goodsbe confiscated, and the executioner buriedhis corpse beneath the scaffold. The dramat-ic end of the Rusca trial resulted in a certainamount of friction among the members ofthe court. The judges, meeting at Thusis,decreed that severe steps be taken to preventany discussions or disagreements degener-ating into brawls11.

On 5th September, the trial began on thenobleman and judge Rudolf Planta, thebrother of Pompejus, of Zernez, in theLower Engadine. Having evaded arrest,Rudolf was accused of being the cause of theinsurrections that had broken out the previ-ous year within the League of God's House,of having fomented unrest in the Leagues,and above all in the Engadine, on ordersfrom foreign powers. The judges of theThusis criminal court, ordered that he beexpelled from the country for ever, that allhis goods be confiscated, and that his houseand the nearby tower of Wildenberg bedemolished.The next trial, against the nobleman and

mayor of Morbegno, Gian Antonio Gioiero,of Val Calanca, also took place in theabsence of the accused. Gioiero, like RudolfPlanta, was charged with having fomenteddisturbances in the Rhaetian Leagues andwith having been paid for that purpose byforeign powers. Found guilty of spying forSpain and France, of complicity with Gio-vanni Battista Prevosti in preventing theattack on Fort Fuentes, of having harmedRhaetian interests by suggesting to theSpaniards in Milan that they should blockall trade with the Leagues, of upsetting rela-tions between the religions, and of corrup-tion in acquiring public posts, he was sen-tenced to permanent exile. The court alsoordered that his house in Val Calanca bedemolished and all his goods confiscated.Serious charges of corruption, betrayal ofthe interests of the Leagues, and close con-tacts with foreign powers led to sentencingto permanent exile, confiscation of hisgoods, and the demolition of house, inabsentia, of the judge Lucius de Mont,mayor of Val Lumnezia.In the case of the Bishop of Chur, foundguilty of high treason, the Thusis court, inthe absence of the accused, confirmed thesentence of perpetual exile already passed onhim by the court of Ilanz in 1607. Thejudges ordered the confiscation of his goods,depriving Bishop Johann Flugi vonAspermont of his ecclesiastical status, andstating that he would immediately be put todeath if he should return to the territory ofthe Three Leagues.In the space of less than two months, theCriminal Court had completed its trials ofthe main defendants. But the activities ofthe court were far from being completed.At Thusis, in the four months that followed,150 sentences were passed. These includedonly one death sentence pronounced in thesecond stage of the criminal court's activi-ties, and concerned Biagio Piatti, who hadbeen found guilty of murder and of havingplotted to kill the Protestants of Boalzo. The

11 For a reconstruction of the Thusis trial from a Catholic view-

point: Cesare CANTÙ; Il sacro macello di Valtellina. Episodio della

riforma religiosa in Italia; Bormio 1999 (reprint), pp. 100-104; Johan

Franz FETZ; Geschichte der kirchenpolitischen Wirren im Freistaat

der drei Bünde (Bisthümern Chur und Como). Vom Anfang des 17.

Jahrhunderts bis auf die Gegenwart; Chur, 1875, pp. 69-78.

[74]

Nicolò Rusca

other sentences passed by the court rangedfrom death in absentia and the confiscationof all their goods for Antonio Maria andGiovanni Maria Paravicini and GiovanniFrancesco Schenardi; to permanent exile forGiacomo Robustelli, Francesco Venosta,Antonio Ruinella, Daniel Planta, AugustinTravers, Teodosio Prevosti, and the burger-master of Chur, Andreas Jenni; to temporaryexile for Nicolò Merulo, who had tolled thebells when Archpriest Rusca was arrested;and for the interpreters of the King of France's emissary to the Leagues, Gueffier,Anton von Molina, and Johann Paul; andheavy fines for the League governorsChristoph Gess (1613-14) and Joseph vonCapaul (1615-16), punished for corruptadministration of their offices and personal

enrichment; as well as for FrancescoParavicini di Ardenno and Fortunat vonJuvalta, and smaller fines for Giovanni Battista Schenardi and Nicolao Carbonera,for having protested on the occasion of FrRusca's arrest in Sondrio.The long list of sentences also included thepastors Georg Saluz of Chur, AndreasStupan, and Ardez and Simon Ludwig ofMalans. The first of these was fined for hav-ing criticized the involvement of a numberof pastors in the proceedings of the criminalcourt of Thusis, for having spoken in favourof the proposals submitted by the Spanishnegotiator to the Leagues in 1617, and forhaving praised Rudolf Planta and blamed anumber of pastors; the second was sen-tenced to temporary exile for having criti-cized the decisions of radical pastors andhaving expressed his support, from the pul-pit, for Rudolf Planta; the third was fined for

having cast aspersions on the criminalcourt. The town of Chur, predominantlyProtestant, and the Council of the Town ofChur were sentenced to pay heavy fines fortheir pro-Spanish attitude and to defray thecost of provisions for the armed bands of thecommunes, since they had not opened thetown's gates to them.

In January 1619, the Thusis Criminal Court,some of whose judges were beginning toshow signs of bewilderment and fatigue, wasfinally dissolved. For some time there hadbeen general reactions of indignation at theaction taken by the court, which was begin-ning to damage the image of the Leaguesand their leaders. The Synod of Pastors,which met at Zuoz after the court's pro-ceedings had been closed down and beenforced by fresh disturbances in the Engadineto break up early, thus reflecting obviouspublic discontent at the way things hadgone at Thusis, suspended Blasius Alexanderand Georg Jenatsch from the exercise oftheir pastoral duties for six months.The Thusis Criminal Court had been notbeen the first such result of the ideologicaldifferences manifesting themselves in theLeagues, nor was it unfortunately the last.Thusis had been preceded by Ilanz and Chur,where the pro-Spanish faction had dealtsevere blows against the pro-French and pro-Venetian factions. At Chur, in 1619, a crimi-nal court favourable to the pro-Spanish fac-tion revised the proceedings of the ThusisCourt, pointed out serious abuses committedby the Thusis judges, reduced or quashednumerous sentences, and passed new ones. Alittle later, as opinions swung perilously firstin one direction and then in the other, a newcriminal court was set up at Davos thatendorsed the findings of the Thusis Tribunal.The way was open for the involvement of theLeagues in war on a European scale.

The Thusis trial, conducted by a criminalcourt that saw itself as a new broom bent oncleaning up the situation in the Leagues,has been the subject, in general, of numer-ous criticisms, last but not least from theprocedural point of view. The episode of thekilling of the Archpriest Rusca is an act thatwas severely criticized, for various reasons,during the months and years that followed,

The house in Thusis,

where the Criminal

Court is said to have

been held in 1618-19

[75]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

and the objectors included Protestants(although many also approved). Thus, forexample, the pastor of Fläsch, Bartholo-mäus Anhorn, the author of a diary thatreported events in Rhaetia in the first half ofthe 17th century, explicitly condemned thekilling of the priest, while FortunatSprecher von Bernegg, a diligent narratorwho was a Protestant, paid the archpriest amost respectful tribute12. In any case, it wasundoubtedly an episode marred by cruelty.

In more recent years, the works of varioushistorians have made it possible, albeitthrough a different way of construing events,to begin to throw light on the 1618 criminalcourt, in particular on the killing of Fr Ruscaand the delicate and complex interplay of thepolitical and religious factors at work in theLeagues and among the dominant powers.Conradin Bonorand, in a full page in his"Quaderni Grigionitaliani"13, concentrates ona series of crucial questions, culminating inan appeal to analyze historical events objecti-vely, avoiding the pitfalls inherent in ideo-logical apologetics. In other words, any sys-tematic simplification should be eschewedthat sought, for example, to present theThusis Court as one that existed to pass sen-tence on men from the Valtellina – in fact, itsentenced fewer than twenty but more thanone hundred and thirty "Bündner"; or aProtestant court that condemned Catholics.At Thusis there were also Catholic judges,and numerous Protestants were found guilty,including one death sentence; or as a courtmotivated exclusively by religious intole-rance. The Criminal Court of Thusis aimed,especially, to neutralize the leading membersof the pro-Spanish faction in the Leagues andto force subjects to obey their prince.Approaching the subject in this way certainlydoes not mean acquitting everyone, inas-much as all were more or less seriously atfault, but merely recording complex eventsobjectively, against the widest background inwhich they took place, and the way in whichthey were interconnected.

Moreover, there is a need to clarify, in thisspirit, what sort of relations there werebetween the Archpriest Rusca and the pastorof Sondrio Scipione Calandrino and perhaps,other Protestant preachers. When accused, at

Thusis, of having intended to have PastorCalandrino assassinated, Fr Rusca repliedthat this was not true and that, on the con-trary, he had always had good relations withthe pastor. The archpriest's words indicatefriendly relations, consisting of courtesy anda mutual exchange of texts for their studies –perhaps, too, some common ground on theo-logical subjects. The chronicler, Sprecher von Bernegg, addsthat he lived in Sondrio for two years asdeputy to the judge trying criminal cases, ina house near the archpriest's. "I was in closecontact with him", says Sprecher vonBernegg, who recalls the archpriest as "a manwith a sober lifestyle, nearly always engagedin study and the performance of his priestlyduties", "a man who had an excellent knowl-edge of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin". Are thesestatements then false, motivated by the needto defend himself against accusations, in thefirst case, or by the desire to pay homage toan outstanding personage, in the second, orinformation on the basis of which we mayspeculate on the existence, in Sondrio, andperhaps in other towns of the Valtellina, ofmore relaxed relations between the church-men of the two religions than is often main-tained? Bonorand, returning to the subject ofFr Rusca's arrest in a work published after hisdeath, raised the interesting point that theCatholic population of Sondrio and of otherparts of Rhaetia had hardly reacted to thepassage of the armed band as it proceededslowly through their territory14, for no realattempt was made to stop the procession andfree the priest either in Sondrio, in the ValMalenco, or throughout its march throughCatholic Rhaetian communes, from Bivio toThusis. Nor, in evaluating the slaying of FrRusca at Thusis should we lose sight of thenumerous abductions, which often ended in

12 Fortunat SPRECHER VON BERNEGG; Geschichte der bündner-

ischen Kriege und Unruhen. Erster Theil. Buch 1-10. Vom Jahre

1618 bis 1628, re-edited by Conradin von MOHR; Chur, 1856, p. 84.

13 Conradin BONORAND; Attuale situazione delle ricerche sulla

Riforma e sulla Controriforma in Valtellina e in Valchiavenna; in:

"Quaderni Grigionitaliani", special number 1991, p. 95.

14 Conradin BONORAND, Reformatorische Emigration aus Italien

in die Drei Bünde. Ihre Auswirkung auf die kirchlichen Verhält-

nisse. Ein Literaturbericht; Chur, 2000, p. 269.

[76]

Nicolò Rusca

the execution of the victims, of a significantnumber of Protestants, seized forcibly fromLeague territories and handed over to theInquisition. If the arrest and killing of FrRusca was brutal and unjustified, so too wasthe seizure of the pastor of MorbegnoFrancesco Cellario (abducted in 1568, he wastaken to Rome and killed in front of CastelSant' Angelo the following year) and that ofpastor Lorenzo Soncino of Mello (who wastaken to Milan and killed in 1588), or theattempts on the life of Pastor Calandrino, theattempt to abduct Pastor Ulisse Martinengo,and many other similar acts recorded up tothe beginning of the 17th century.

One of the last points that remain to bemade concerns the polarization of the fac-tions that took place in the Leagues and subject territories – a development that also involved many exponents of Catholicismand Protestantism. At Thusis, the Leagues'judges were inclined to regard as of sec-ondary importance the fact that Fr Ruscawas a leading clergyman in the subject ter-ritories through whose arrest a seriousblow had been struck against the Romanchurch in the Valtellina. In their opinion,the fact that they were giving a rebel asound lesson was more significant. As –according to the chronicler Juvalta – PastorCaspar Alexius said: "These subjects are anobdurate lot and hold their heads too high:we must teach them how to bow them andhumiliate them". But Thusis did not suc-

ceed in turning the people of the Valtellinainto obedient subjects; on the contrary,they put a final end to any chances of peace-ful coexistence.To conclude, a brief mention of the main,more easily accessible sources of informa-tion regarding the Court of Thusis and thetrial of Nicolò Rusca, consisting of records ofthe trial and some contemporary writings.The State Archives of Graubünden in Chur(Staatsarchiv Graubünden Chur AB 5/13),"Strafgerichtsprotokoll Thusis 1618 undMalans 1621", contain the minutes of thesessions of the Criminal Court of Thusis.The text available appears to be a copy ofthe Thusis minutes, made for the League ofthe Ten Jurisdictions, to which is added acopy of the minutes relating to the activi-ties of the criminal court of Malans.Christian Kind15 believes that the originalminutes were destroyed when the verdictsof the Thusis trials were revised by thecourt of Chur in 1619. The copy kept in theChur State Archives lacks the pages givingthe names of the members of the court,which are either missing or have beendamaged. This makes it impossible to knowexactly who the members of the criminalcourt of Thusis were.Another version of the court's proceedings,shorter than the one just referred to, ofwhich it might be a summary, has beentranscribed in the fifth volume of therecords kept by the Rhaetian historianConradin von Mohr, "Documente zur vater-ländischen Geschichte. Sec. XVII. 1538-1681", to be found in the State Archives ofGraubünden (Staatsarchiv GraubündenChur AB IV 6/22).

The main printed sources regarding theproceedings of the Criminal Court ofThusis, especially the trial of the Archpriestof Sondrio, Nicolao Rusca, consist of thecontemporary chronicles of the Leagues ofBartholomäus Anhorn, Fortunat Sprechervon Bernegg, and Fortunat von Juvalta, aswell as of Giovanni Battista Bajacca ofComo. Bartholomäus Anhorn, a Protestantpastor at Fläsch and Maienfeld, wrote Der

Graw-Pünter-Krieg 1603-1629, a ten-vol-

15Christian KIND; Das zweite Strafgericht in Thusis 1618; in:

"Jahrbuch für Schweizer Geschichte", 1882, p. 292.

Fortunat Sprecher

von Bernegg, the

League magistrate

who met Fr Rusca

and spoke well of him.

This engraving is in

the Rhaetian Museum

at Chur

[77]

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

ume diary published by Conradin vonMohr, in the "Bündnerische Geschichts-schreiber und Chronisten" series in 1862.Fortunat Sprecher von Bernegg, whohailed from Davos, is the author of Historiamotuum et bellorum (in two volumes, thefirst of which covers the period 1608-1628and the second the years 1629-1644).Sprecher von Bernegg held various posts inthe Valtellina, personally made theacquaintance of the Archpriest of SondrioNicolò Rusca, whose neighbour he was fortwo years, and carried out various diplo-matic missions on behalf of the RhaetianLeagues.While the first two authors described cur-rent or recent events, the third, Fortunatvon Juvalta, wrote, towards the end of hislife, Commentarii vitae (translated intoGerman and published by Conradin vonMohr in Chur, in 1848, under the titleDenkwürdigkeiten, 1567-1649), a book ofmemoirs full of autobiographical refer-ences that, in particular, describes thetroubled lands of Rhaetia. Fortunat vonJuvalta was born at Zuoz, in the Engadine,attended Latin schools in Germany, wastaught by the Jesuits, for two years workedas a clerk for his uncle, the Bishop of ChurPeter de Raschèr, held administrative postsin the Valtellina, and was appointed bish-op's bailiff for Fürstenau in 1641. AProtestant who was in constant touch withCatholics, von Juvalta was tried by theJudges at Thusis, in 1618, and sentenced toa heavy fine.

His description is not without resentmenttowards his judges, but is at the same timefull of detail regarding the court's proceed-ings. Felici Maissen (Die ältesten Druck-

schriften über den Erzpriester Nicolò

Rusca, in: “Zeitschrift für SchweizerischeKirchengeschichte”, 54/1969, pp. 211-239)finally gave convincing proof, based onmeticulous comparison, of the validity ofthe chronicle of events at Thusis written byGiovanni Battista Bajacca of Como andpublished as an appendix to his biographyof the Archpriest of Sondrio, NicolaiRuscae S.T.D. Sundrii in Valle Tellinaearchipresbyteri anno MDCXVIII Tuscianaein Raethia ab haereticis necati vita et mors.The biography and chronicle of Bajacca,

who was a lawyer and a secretary to thepapal legate Sarego, were re-published inComo, in 1958, by the historian PietroGini. The appendix consists of a long letterfrom Bajacca to the capuchin monk Tobia,guardian of Melzo.

Paolo Tognina

Head of evangelical broadcasts for ItalianSwiss Radio and Television, Novaggio; for-merly pastor of the evangelical reformedchurch of Locarno

Don Nicolò Rusca, the "good shepherd" in the stained-glass window made in 1935 for the presbytery of the Collegiate Church of Sondrio.

“Hate the error, but love those who err”

The Good Shepherd Nicolò Rusca

[80]

Nicolò Rusca

On 8th November 1927, on behalf of onehundred and twenty-six parish priests fromthe Valtellina, the Archpriest of SondrioMonsignor Pietro Maiolani petitioned thenew Bishop of Como, Monsignor AdolfoPagani, to contact the Holy See. They want-ed the Vatican to initiate the beatificationproceedings of Fr Nicolò Rusca, the "arch-priest martyr", as he was commonly knownand invoked in our parts.Among the arguments in support of thispetition to Pope Pius XI (previously theMilanese Cardinal Achille Ratti), two recentcanonizations of priests were cited: on 23rdMay 1920, Benedict XV had beatified the pri-mate of Ireland, Oliver Plunket, killed inLondon in 1681, and the same Pius XI, atPentecost 1925, had canonized Jean-MarieVianney, the "Curé of Ars".The petitioners were representative of wide-spread opinion, both in the diocese of Comoand in the Ticino. Their hope and wish wasto honour the martyr and shepherd of souls,the heroic Archpriest of Sondrio, "a jewelamong priests and a model among HolyShepherds who fought for the faith and atrue martyr of the Catholic Church […] willspur many on to love, uphold and defend thefaith of their fathers with greater vigour […]a shining example for shepherds of souls,uplifting spirits at times discouraged in theexercise of their sacred ministry".This letter did not achieve the perhaps over-ingenuously hoped-for effect. However,together with the efforts of Fr LuigiGuanella (also beatified in 1964) for the"Rusca cause" in the early 1900s, it encour-aged numerous suits by MonsignorAlessandro Macchi, Monsignor Pagani's suc-cessor. He took the matter to heart andreached an agreement with the Bishops ofLugano and Chur regarding territorial com-petence. On 3rd November 1932, heobtained permission from the Congregationof Rites for the beatification proceedings tobe held in Como.In the meantime, he had assembled a per-manent committee and set up the "Collegeof Petitioners", consisting of all the vicarsforane, the town parish priests, the canonsfrom the cathedral, and other eminentpriests. The Informative Diocesan Procee-dings were celebrated in 1935. The officialrecords were sent to Rome and the way was

clear for the case to go forward. But for var-ious reasons it was not to be taken up againuntil 50 years later, with the new diocesanproceedings solemnly concluded in theSondrio Collegiate Church on 26th April1996. However, the long interval had notbeen in vain. Indeed, all the documentsrequired have been examined, and muchnew material has been found, collated andstudied in depth in Como, Milan, andabroad. It is hoped that the positio will soonbe published.