New Approach to Scales (Preview)

-

Upload

adam-smale -

Category

Documents

-

view

2.003 -

download

5

description

Transcript of New Approach to Scales (Preview)

i

New Approach to Scales for Guitarists: A Practical Modern Direction

Adam Smale

© 2011 by Adam Smale

All Rights Reserved

ii

New Approach to Scales for Guitarists: A Practical Modern Direction

Published by Adam Smale and Guitarpreneur Productions 275 Park Ave, Brooklyn, NY, [email protected]

© 2011 by Adam Smale

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me-chanical, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Adam Smale.

iii

Acknowledgments

This is my first book. Thank you for searching it out and purchasing it. I hope, like all good books, that it challenges you and changes you in good way.

There are some people which come to mind that have helped me, by way inspiration, in motivating me to collect my thoughts, my views, my discoveries, and put them down on paper to share with you, the reader, and the musician.

My family has got to be some of the most supportive folks on the planet. Thanks Mom and Dad for not trying to convince me too hard to become a doctor or lawyer. Trust me. It wouldn’t have worked out anyway. My brother Bob has always been supportive, even when I was probably unaware of it. But wait a minute, didn’t you want to be the author, Bob?

A nod to Matthew Warnock, who I admire with his drive to seemingly tireless work ethic to not only strive for “more” in music, but also is compelled to find time to write about music and musicians. I don’t know how you do it.

Much gratitude goes to Tom Knific, Dr. Scott Cowan, and Dr. Matthew Steel, for allowing me the opportunity to absorb a wealth of information while attending Western Michigan University. The concepts were brewing for this book while I was attending WMU. On other levels, besides music or scholarly pursuits, I also learned other valuable information from you all.

Here are just a handful of musicians I owe tribute for helping to inspire me directly with their talent and innovative, true-to-self approaches: Lenny Breau, Bill Evans, Chet Atkins, Jim Hall, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Tal Farlow, Joe Henderson, Ed Bickert, Lorne Lofsky, Cannonball Adderley, Chick Corea, Edward Van Halen, Frank Zappa, Alan Holdsworth, Albert Lee, McCoy Tyner, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, and Wayne Shorter.

iv

“The illiterates of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn” Alvin Toff ler

“I can’t understand why people are frightened of new ideas. I’m frightened of the old ones” John Cage (1912-1992)

Cool Quotes...

v

Foreword

The Count InI know what you are thinking. How can there be a new approach to scales? Scales is scales, right? Well I believe I have shed new light on an old topic. The basic material is the same. It is how you organize, see it, and hear it that is going to be very different from the standard guitar pedagogy.

All StylesIt doesn’t matter what style of music you play, this book is for you. Take the ideas in this book and apply them to what you do, whatever style. I admit that this book has a kind of a Jazz Improvisation slant to it. That is my background. It includes what some may refer to as “jazz scales.” There may be some scales in here that some jazz guitarists may find unfamiliar. That’s OK. Take what you want from the book. Maybe you can discover new applications of my concepts and apply them to what you do in a way I never thought of. Go for it! That is why I am putting this book out there. Isn’t music amazing? Everyone can take the same 12 notes and all sound different.

Hit and MissI could have called this book How to Find all the Good Notes on Your Guitar. It is a bit vague for a title but essentially, it is the end result. I used to be happy with my playing some of the time. Sometimes, by accident, my ideas sounded good. Other times, ideas were unclear, not so good. “Why do some people seem to sound good all the time?” is what I thought. I knew I was playing the “correct” scales. Maybe you have wondered this too, or in a similar predicament right now. I wanted to enter into that world of knowing how to sound good, an awareness. By implementing what I have laid out here in this book, hopefully you will not be a hit and miss player anymore either.

Why?There comes a time in a serious musician’s mind when they develop beyond what has been handed down to him from teachers of the past and starts down a path of self discovery. It is a time when we want a deeper level of understanding of what we do as musicians, and possibly, how one can do it better. However, there is nothing wrong with following your teacher’s guidance. Everyone has to start somewhere. I hope that your teacher is sending you down a path for such self-discovery if you have a teacher. What I am referring to is the desire for more. How do I make these learned materials my own, and begin to “own” these same materials? How do I develop my own approach? How do I develop my own sound? This book is a small chunk of my path—a start if you will—that I am sharing with you fellow guitar players.

vi

Sometimes this type of search leads to new discoveries, and sometimes it leads to innovation. A long list of famous musicians could be cited from many genres that have used the same basic 12-tone system to come up with something new and fresh. I am certain most of you would agree. I hope this will be a new and fresh approach to many guitarists, and bassists.

Kind of GreenI have always envied piano players. You could say I have “pianist envy.” Because the keyboard is laid out in a simple, logical, repetitive manner, it makes it a little easier than most instruments to get the muscle-memory part of learning musical patterns: scales, arpeggios, and licks. Piano is the epitome of linear. It is also the epitome of harmony, but harmony is not the scope of this book. Well, not harmony as a topic unto itself. However, the very topic of this book is very much related to harmony. In short I want you to start thinking that a scale is a linear chord, and a chord is a vertical scale.

With piano, once you get patterns under your fingers, you can easily transfer these musical patterns in any range. Guitar does have some of these same inherent qualities, but as you fellow guitarists may know, you cannot exploit this concept as far on guitar as on you can on piano. Guitar is linear as well, but you have to multiply this linearity by six layers—seven if you are in my shoes—each layer being that of a different string. In addition, those layers, or strings, overlap. Piano is just one straight line, without having to jump to numerous keyboards in order to play a different range of notes like you have to do on guitar by jumping to different strings.

Moreover, now factor in the standard tuning of a guitar. This presents another challenge: The strings are not tuned to a constant interval between each string. This tuning lends itself nicely to play all the common chords you would find in chord encyclopedias, but this interrupts the flow during performance of playing lines and melodies. One way to fix it is to change the tuning. Trust me, I thought about it. When I was developing these ideas, I had already been playing guitar in standard tuning for 25yrs. I just did not want to learn guitar all over again with a new tuning. Tuning your guitar in constant 4ths, for example, would make for simpler string transference. (keeping the exact fingering to different strings and areas of the guitar neck) It would certainly make it more easier in that it would create an environment closer yet to a piano.

Furthermore, by changing the tuning you could keep many of your identical chord shapes that you did on your bottom 4 strings and transfer those shapes through to the upper strings as well. On the other hand, your notes on your 1st and 2nd strings would be off from where you are used to them being tuned. It could take some getting used to. You certainly can’t whip out your trusty, dusty, open E Chord anymore. Oy Vey! No AC/DC for this cat anymore!

vii

Tuning your guitar in 5ths, like violin or cello, would probably make playing lines a little easier. You can produce more “leaps” without stretching your hand as far, not to mention there would be a large increase in range over the span of 6 strings. Nevertheless, all your chord shapes that you used to know are now nonexistent. If you learned guitar from scratch with any of these types of consistent-interval turnings it might not be so bad. I for one was not going to go there. That got me to thinking though. How do I create this piano-like consistency on guitar in standard tuning? Since I couldn’t change the guitar, I had to change the organization of it.

What I came up with is what I will soon share with you here in this book. I do not know if I am the first person to think of it, but I have never heard of it before. I have not read it in any guitar books, or magazines. It seemed somewhat revolutionary to me. Then I started realizing its potential and started working with it and discovering more. Then I got really excited!

viii

Just the Facts Ma’am (About the Author)

Adam Smale is a guitarist, composer, teacher, and life-long student of music and the guitar. While growing up in rural Northern Ontario, Canada, Adam fell in love with music and the guitar at a young age. By 9 years old was figuring out songs from his Dad’s record collection. Scotch Boogie was the first song he learned by ear, recorded by Canadian guitarist Ken Davidson. Then it was on to The Ventures, various Bluegrass tunes, some songs Chet Atkins recorded, then the Beatles, ZZ Top, and Van Halen. He became a member of the musician’s union at the age of 12. By 14, Adam was on the road, gaining valuable experiences as a performer at bars, weddings, and community dances.

Upon reading an article in a guitar magazine on his then guitar hero, Eddie Van Halen, the young guitarist distinctly remembers the rocker mentioning a guitarist from England whom he was giving praise at the time. It was none other than Alan Holdsworth. When hearing a couple of Holdsworth’s albums he knew that he had lots to learn about music and the guitar. So he worked hard on being the best guitarist he could possibly become from then on.

Much later, inspired by the late Lenny Breau, Adam began to play with a fingerstyle technique, albeit, also with the help of a thumb-pick; a return to his “Chet Atkins” days. He mainly plays two 7-string guitars: an electric he designed and had built for him, and a nylon string acoustic guitar he designed and built himself. Adam has played many styles of music over his career but now primarily performs Jazz. Somewhat recently began to immerse himself into the exciting world of Flamenco.

Adam has conducted master classes and seminars in Canada & the US, for Guitar Workshop Plus, the National Guitar Workshop, and Western Illinois University, as well as juggling private students over the past 20 years. Adam holds a Masters degree in Jazz Performance from Western Michigan University, and a Bachelor degree in Jazz Studies from Humber College. He currently lives in New York City.

ix

Contents

Acknowledgements……………………………………………...... iiiForeword…………………………………………………………....... vJust the Facts M’am (About the Author)………………………. viiiYou Got a Lot of Splainin’ to Do………………………………..... 1Come to Terms…………………………………………………........ 6Rules of the Road………………………………………………...... 8On With the Show. This is it!......................................................... 9Master List of Major Scales…………………………………….... 10

Scales by Chord Type

Major Chord Types……………………………………………………….... 13Major Scale (Ionian)……………………………………………..... 14Lydian……………………………………………………………….... 19 Harmonic Major (Ionian 6)……………………………………..... 24Lydian 6……………………………………………………………… 29Lydian #5…………………………………………………………...... 34Ionian #5…………………………………………………………...... 39Lydian #9…………………………………………………………...... 44Lydian #9 #5……………………………………………………….... 49

Minor Chords Types………………………………………………………... 55Dorian……………………………………………………………….... 56Natural Minor (Aeolian)…………………………………………… 61Phrygian…………………………………………………………….... 66Melodic Minor……………………………………………………..... 71Harmonic Minor…………………………………………………….. 76Melodic Minor #4…………………………………………………... 81

Dominant Chord Types…………………………………………………… 87Mixolydian………………………………………………………….... 88Lydian 7…………………………………………………………….... 93Diminished Dominant (half-whole diminished)....................... 98Altered……………………………………………………………...... 103Whole Tone………………………………………………………...... 110 Mixolydian 2 6…………………………………………………....... 116Mixolydian 6……………………………………………………….... 121Mixolydian 2 n6…………………………………………………........ 126Mixolydian 9 #9 13……………………………………………….... 131

x

Half Diminished Chord Types................................................................ 137Locrian……………………………………………………………....... 138Locrian 9…………………………………………………………....... 143Locrian 9 13………………………………………………………..... 148Locrian 13………………………………………………………....... 153

Diminished Chords…………………………………………………............ 159Diminished Scale (whole-half diminished)……………………………. 160Locrian 7…………………………………………………………...... 165

Scales by Scale Family

Modes of MajorIonian (Major)………...........……………………………………..... 14Dorian……………………………………………………………….... 55Phrygian…………………………………………………………….... 66Lydian……………………………………………………………….... 19Mixolydian………………………………………………………….... 88Aeolian (Natural Minor)…………………………………………… 61Locrian……………………………………………………………....... 138

Modes of Harmonic MajorIonian 6 (Harmonic Major)……………………………………..... 24Locrian 9 13 (Dorian 5)………………………………………....... 148Mixolydian 9 #9 13……………………………………………….... 131Melodic Minor #4…………………………………………………... 81Mixolydian 2 n6…………………………………………………........ 126Lydian #9 #5……………………………………………………….... 49Locrian 7…………………………………………………………...... 165

Modes of Melodic MinorMelodic Minor……………………………………………………..... 71 Lydian #5…………………………………………………………...... 34Lydian 7…………………………………………………………….... 93Mixolydian 6……………………………………………………….... 121Locrian 9…………………………………………………………....... 143Altered……………………………………………………………....... 103

Modes of Harmonic MinorHarmonic Minor…………………………………………………….. 76 Locrian 13………………………………………………………....... 153Ionian #5…………………………………………………………...... 39 Mixolydian 2 6…………………………………………………....... 116Lydian #9…………………………………………………………...... 44

xi

Independent ScalesLydian 6……………………………………………………………… 29Whole Tone………………………………………………………...... 110Diminished Dominant (half-whole diminished)....................... 98 Diminished Scale (whole-half diminished)…………………….. 160

1

You Gotta Lotta ‘Splainin’ to Do

Necessity is the Mother of InventionLike most out-of-the-box ideas, they end up often being something very simple. As a kid, I remember a story once told to me about how during transportation of some large, oversized object on a transport flatbed trailer, a group of engineers were baffled on how to get their cargo to be able to fit underneath the overpass that was on route. Either they miscalculated the overall height of their cargo, or the overpass measurement was off. Nevertheless, they were in a pickle—they where a little under 2 inches to tall to fit underneath the very solid concrete structure.

Should they chisel away some of the concrete on the overpass to allow it to fit? Not an option. The highway authorities would never allow damage to such a structure even if it were to be repaired afterward. Should they shave off some of the roadway surface to allow the truck to slip underneath? Again, not a good option. Perhaps they could build a temporary road around the overpass? That would just be way too costly. Besides, they were causing traffic flow problems as they pondered their predicament. Something needed to be done quickly.

As the engineers were scratching their heads as what to do, along came a young child on a bicycle. The child showed some interest in their dilemma. I’m sure the “adults” were forthright in their comments to the youngling. “Run along now. We have very important serious, adult, issues to deal with.” I can picture something like this taking place. Then, astonishingly, out popped from the child’s mouth “Why don’t you just let the air out of the tires?” I am sure these educated engineers’ faces turned white—or maybe red with embarrassment. Such a simple, eloquent, quick, and inexpensive solution was staring everyone in the face, yet the best solution had been illuminated to all involved by an innocent child. Maybe it is because of that story I try to keep an open mind of letting things reveal themselves without thinking too hard about them, rather innocently.

My New Approach in a Nutshell Maybe my idea is not all that revolutionary, at least compared to the theory of relativity. But by mapping out the guitar neck in an easier way can’t be bad, right? I like killing two or three birds with one stone, so I applied this new scale approach to also include passing tones. I also wanted to make sure I was getting good chord tone timing under my fingers as well as in my ears. If you do not know what passing tones, or what chord tone timing is, you will once you begin working with this book. I take things even further and apply my new approach to some not-so-common scales. However, the purpose of this book is to learn, or relearn, the following four things:

2

1. A new approach to mapping out the notes of various scales so that your melodic lines have more continuity, more fluidity in executing them. It will also help things “fall under your fingers” a little easier, making scalar ideas easier to play, easier to memorize, and an easier (or at least new) way to connect ideas. It will get you to view your fretboard differently, opening up new possibilities.

2. Implementing passing tones in scales you may already know. Because most scales contain 7 notes and most of the music we play has an even number of beats (or subdivisions of beats), the scale in its raw form (an odd number) doesn’t match up with the even-numbered beats. Therefore, you simply add an extra note. Easy! I’ll show you where in each instance. This also ties into the next item.

3. To relate the scale to a chord. To now base your scale around the chord tones. (Root, 3rd, 5th, 7th [or 6th]) As a happenstance, this is where the workload is also drastically reduced. Instead of learning a pattern off of each note of the scale, you now only worry about 4 notes to target based off the chord tones. Meanwhile resulting in just 2 patterns for each scale. You will begin to see the chord within the scale of choice. Often there are many choices of scales for a chord.

4. Implementing chord tone timing so that your lines sound strong. In other words,you are spelling out the chord changes with your note choices even though no one may be “comping” (accompanying) for you. Another way of thinking of it: in hearing your melodic line, the chord changes are also being implied. This is what makes your ideas sound strong, so you sound like you know what you are doing. If something holds up on its own, imagine how it will sound when you start adding in other musical parts, other musicians to the over all picture.

To Sum it UpInstead of “Well, here’s the notes of the scale, let’s play them mindlessly up and down because I heard I’m supposed to do that.” You don’t practice scale for the sake of playing scales. You practice scales to develop your fingers and your ears to play without thinking in a performance context. If you are going to practice scales, why not do it with greater purpose and consistency of outcome?

3

Dig This

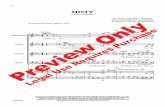

To start with, I am reorganizing the fretboard into 4 notes per string (passing tones included) in string sets of 2 strings at a time in most cases. With some scales you can’t include a passing tone. Here is a diagram of an incomplete F Major scale on the first 2 strings, low E & A (Ex. 1):

Ex. 1

About the Fretboard Diagrams Throughout the Book

On string 6 you have 4 notes. On string 5, with the passing tone,marked “P”, again you have 4 notes. By keeping it 4 notes per string everything stays consistent. Now here is the real beauty of it all. That exact same pattern transfers to the next string set. (4th and 3rd strings) See Ex. 1.1

Solid Circles = Chord Tones spelled out inside the scale

Hollow Circles = Non Chord Tones

Arc = A slide into the next note, ascending or descending, not necessarily a Slur but it could be if you wish

P = The Passing Tone (non-scale tone)

The chord tones will also be indicated with the proper Scale degree. (R, 3, 5 & 7) as an example.

4

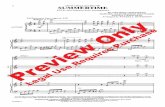

Ex.1.1

You now have exactly the same repetition on strings 4 and 3. Cool, right? Now keep that same concept for strings 2 and 1. See Ex. 1.2

5

Ex. 1.2

The exact same pattern is repeated yet again, only shifted up one extra fret to adjust for the 2nd string being tuned down a semitone. But you knew about that already, right? Now you have the whole picture. Since the 1st and 2nd strings are still tuned a 4th apart, as the previous string sets, not one thing has to change with our pattern on this last string set. This basic concept, repetition on every 2 strings, plus the addition of a passing tone, will apply to any 7-note scale 95% of the time, and is the basis for this book.

By mapping out the fretboard in this new repetitive fashion, it creates more flow in execution once you wrap your head and fingers around it, all the while expanding the range (low to high) with relative ease because your fingers follow the exact same pattern. Just like piano! You have to forget about the old “box method.” This is thinking outside the box. That is exactly what I feel the “box method” does: box you in!

Wrapping UpThis is the concept in brief. I will be inserting diagrams as needed to help you “see” how it works for other types of scales covered in this book at the appropriate times. Because this is new, it might not come too easily at first. Like anything new, be patient and work with it. Once you get it you will not want to think of the old way of mapping out scales again. Actually, there is nothing wrong with the old way of mapping out scales on the guitar neck. This new way is just more practical, I believe. It is one more thing to add to your arsenal of overall musicianship, once you see the potential. Like anything else, practicing with a metronome is a must.

13

Major Chord Types

14

Scale Formula:R 2 34 5 6 7R

15

16

17

18

Follow Up1. Now practice the Major Scale in the keys of B, E, A, D, G, F#, B, E, A, D, G & C. (Refer to the Master List of Major Scales on pg.10 if you need help knowing what notes are in each key) 2. Remember, now that you have the 2 basic patterns down for this key (F), it will be exactly the same 2 patterns for every other key. Therefore, it will be easy to transfer these to the remaining keys. It makes life so much easier, and less daunting. Pattern 1: R and 5th; Pattern 2: 3rd and 6th.

3. Always practice with a metronome.

4. Be aware while you are practicing where the down beats are. (1, 2, 3, 4) Make sure your chord tones are landing on the “down beats”, non-chord tones on the “up beats”. One suggestion is to tap your foot on beats 1 & 3 to help keep yourself anchored with your time.

5. Practice in 3/4 as well as 4/4. When in 3/4, tap your foot on beat 1 each time. In 3/4, beat 1 is the strong beat.

6. After awhile you’ll feel where those strong resolution points are to play into, or use as possible anchors to end your phrases. (4/4 = beats 1 & 3; 3/4 = beat 1)

Someone said to Chet Atkins “Man, that guitar sure sounds good!” Chet set the guitar down on a chair and asked him “OK, how does it sound now?”

Cool Quotes...

170

Thank yourself for making it to the end!

“We need more emotional content...Don’t think, feel!...Don’t concentrate on the finger or you will miss all that heavenly glory” Bruce Lee (1940-1973)

Cool Quotes...

New Approach to Scales for Guitarists should be in the hands of every modern guitarist today. This book not only teaches you a completely new way of organizing your guitar fretboard, but will also change the way guitarists relate scales to chords.

Learn the science of how to make your musical statements sound strong and cohesive. This book is also a compendium of common scales used in today’s ultra-modern harmonic-melodic vocabulary: an extremely comprehensive book for contemporary music.

If you need to break out of some ruts, this book is for you. If you need to know how to move around effortlessly on your fretboard, this book is definitely for you.

The author, Adam Smale, shows you his unique method using examples for each scale in its full range using Standard Notation and Guitar TAB, as well as utilizing Fretboard Diagrams to fully comprehend this thrilling new advancement in guitar pedagogy for all players and all styles.

www.NewApproachtoScales.comwww.AdamSmale-jazz.com