Name€¦ · Goodbye Lenin? A Centenary Perspective The Russian Revolution should not be confined...

Transcript of Name€¦ · Goodbye Lenin? A Centenary Perspective The Russian Revolution should not be confined...

St Brendan’s Sixth Form College – History Transition Task

In order to give you an introduction to History A level and prepare you for the best possible

start we would like you to complete the following tasks. This work will become the foundation of

your first 4 weeks of study and will ease the transition between school subjects and college

subjects. The details are as shown below:

Name:

Handing in: Please Bring a digital and paper copy with you to your last History

lesson in week 1 ( you will be reminded in your first lesson)

Key terms when studying Russia 1917 - 1991 Term Definition

Feudalism

Capitalism

Socialism

Communism

Social class

Proletariat

Bourgeoisie

Revolution

Imperialism

Democracy

Authoritarianism

Command economy

Historical interpretation

Analyse

Evaluate

Extent

Significance

Change

Continuity

Cause

Subject: Russia 1917 – 1991: From Lenin to Yeltsin

Task 1 Glossary: Knowing the key terms will enable you to understand the work you will

do in History. Please complete the definitions for each of the following key terms.

Task 1 Glossary: Knowing the key terms will enable you to understand Geographic

language, access the other tasks and make rapid progress when you start. Please complete

the table, finding the ‘Geographical’ definitions of all the terms

Task 2: Read the following extract from an A Level textbook and answer the questions on the next

page.

Task 2: Answer the following questions using the extract on the previous page

1. What was Lenin’s government like? Give at least three points

2. How did Lenin come to power?

3. What does the extract mean by “a mix of utopian vision and skilful political compromise”?

4. In what ways did Stalin build on Lenin’s achievement?

5. How did Khrushchev change the way Russia was governed?

6. Why was Khrushchev replaced with Brezhnev?

7. What were the problems the leaders faced by the 1980s?

Task 4 – Lenin’s Legacy. Read ‘Goodbye Lenin’ and make notes on Lenin’s legacy and the October

Revolution using the Cornell Method...

Sample Footer Text 6/16/2020 30

Make a note of anything you don’t understand. Try and find out what it means. If you still don’t understand ask in your first lesson. The only stupid question is the one you don’t ask!

Task 3- Research task to extend your learning further

Find out about Russia in 1917. Here are some ideas to help you with your

research…

1. Geography e.g. How big was Russia? How urban / rural was it?

2. Politics e.g. Who was the Tsar? What happened in February 1917? What

happened in October 1917?

3. Society e.g. What was the structure of society (from bottom to top)?

What were peoples’ lives like?

4. Economy e.g. What were the main ways people made money in Russia? How

industrialised was its economy?

You could compile your findings as bullet pointed notes, a mind-map, a poster,

flash cards… it’s entirely up to you!

Goodbye Lenin? A Centenary Perspective The Russian Revolution should not be confined to 1917. The legacy of its

leader and chief ideologue lives on in all its terrible contradictions.

James Ryan | Published in History Today Volume 68 Issue 6 June 2018

Throughout its entire history the Russian revolutionary movement included

within it the most contradictory qualities.

– Vasilii Grossman, Everything Flows, 1961.

More than 80,000 football fans will descend on Moscow’s Luzhniki stadium on 15 July for

the World Cup final. As they approach the recently renovated Olympic stadium, a large

statue of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin will come into sight. Almost three decades after the fall of the

Soviet Union, his image remains ubiquitous in Russia; in neighbouring Ukraine, the former

Soviet republic, no statue of him is left standing. In Russia, by contrast, almost every city and

town still has a Lenin street, as well as a statue. In Moscow, his embalmed body still lies on

display at the heart of the city. Yet, despite his status as one of the major figures of the 20th

century, Lenin spent most of his life in obscurity. Few people in Russia or anywhere else had

heard of him at the beginning of 1917. When he came to power later that year, he had fewer

than seven years left to live.

Lenin’s journey into the history books was an extraordinary one. On 9 April 1917, a group of

Russian revolutionaries, with Lenin at its head, boarded a train in the city of Zurich in

neutral Switzerland, bound for the north German coast. It was a train journey that, in the

words of the historian Catherine Merridale, ‘changed the world’. The trip through wartime

Europe was fraught with dangers, but a week later Lenin and his entourage emerged from

the sealed train at the Finland Station in St Petersburg (or Petrograd, as it was renamed

during the war). Seven months later, this group of revolutionaries had overthrown the

provisional government in the Russian capital and had set about trying to establish a new

type of political power, not just in Russia but throughout the world.

Lenin’s address at the Finland Station, Petrograd, 1917, by Nicolai Babasiouk, 1960.

The Russian Revolution is about much more than the events of 1917. The term ‘Russian

Revolution’ embraces both the February and the October Revolutions of that year, the latter

when Lenin’s Bolsheviks seized control of the capital. More than that, however, the

Revolution consisted of a process of political, social, economic and cultural transformation

that certainly did not end in 1917. A year later the meaning of ‘Soviet power’ was still in flux:

1918 witnessed such consequential events as the dissolution of Russia’s first truly

representative parliament, its exit from the First World War and the outbreak of the main

phase of the Civil War. The Soviet state was consolidated only in the 1920s. Most historians

of the Revolution – Russian as well as Anglophone – extend its timeframe to the early 1920s,

if not later.

Discussions of the centenary, by specialists and non-specialists, have suggested a great deal

of complexity. This has been reflected in publications and conversations that seek to capture

what the Revolution meant to different political parties, to political and social elites and

perhaps especially to ‘ordinary people’. The historian Steve Smith has written that

‘revolutions are not created by revolutionaries, who at most help to erode the legitimacy of

the existing regime by suggesting that a better world is possible’. Smith’s point is that

revolutions occur through popular action during times of ‘deep crisis’ in the existing order

and that the role of revolutionaries is to direct that action. In addition, one of the most

prominent recent trends in studies of the Revolution has been to examine its unfolding

outside the major capital cities: the relationship between the political centre and the

peripheries was complex. Power did not simply flow from the top to the bottom.

Yet historians should be careful not to make the centre peripheral to the story of the

Revolution and should avoid adopting a romanticised conception of revolutions as ‘festivals

of the oppressed’ (Lenin’s own characterisation). The course of the Revolution was

determined above all by Lenin and his ruling Bolshevik party, often by mobilising ‘the

people’, but often also by using force against them. Hence, both Lenin (the man) and

Leninism (the ideology) need to be given central place in any discussion of the centenary of

the Russian Revolution.

The historical significance of Lenin

In 1935, Lev Trotsky, one of the Bolshevik leaders during the autumn and winter of 1917 and

the architect of the Red Army, wrote in his diary that ‘if neither Lenin nor I had been present

in Petersburg, there would have been no October Revolution: the leadership of the Bolshevik

Party would have prevented it from occurring – of this I have not the slightest doubt!’ This

has become a standard view of the October Revolution. It is important, however, not to

embellish the role of the individual. Trotsky exaggerated the significance of Lenin (and

himself) and the extent to which he had to convince his own party to take power. It seems

that in the autumn of 1917, Russia was going to become a socialist, soviet country anyway, at

least temporarily. That is because the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, scheduled to

meet on the day the Bolsheviks moved to take power, was due to vote in favour of forming a

government of exclusively socialist ministers, based on the authority of the Congress. Lenin,

however, wanted to seize power before the Congress met in order to avoid coalition with

more moderate socialists. Even after his seizure of power, there was a strong chance that

more moderate socialists, including the more moderate Bolsheviks, would forge a coalition

government that would rule until a democratically elected parliament was convened. But the

more radical Bolshevik faction led by Lenin and Trotsky managed to ensure that there would

be no place for moderate socialists in government and that ‘Soviet’ power would not be

compromised by the existence of parliamentary democracy.

What was the October Revolution for?

For many, Lenin sits alongside Hitler and Stalin as a brutal dictator; for others – though they

are fewer than they once were – he represents the ‘authentic’ spirit of 1917, until it was

‘betrayed’ by Stalin. For others still, Lenin’s historic role is more ambiguous. But it is

important to recognise the contradictory character of the October Revolution, if we are to

arrive at a suitably complex understanding of Lenin and Leninism.

Key questions need to be asked. What was the October Revolution actually for and why did

the Bolsheviks take power? First, Lenin and his fellow Bolsheviks were absolutely committed

to the triumph of socialism and later communism around the world. They were all (including

Stalin) supremely theoretical politicians, for whom matters of doctrinal orthodoxy were of

cardinal importance. They were prepared to use opportunism and cunning, lies and

brutality, but they were motivated more by theoretical vision than by personal interest. This,

however, is far from an accepted view. Let us take, for example, the most recent biography of

Lenin in English, by Victor Sebestyen, published in 2017 with the title Lenin the Dictator.

Sebestyen seems to consider that parallels exist between Lenin and Donald Trump. Like

Trump, ‘in his quest for power, Lenin promised people anything and everything … He lied

unashamedly. He identified a scapegoat he could later label “enemies of the people.” … Lenin

was the godfather of what commentators a century after his time call “post-truth politics”.’

Sebestyen acknowledges that Lenin was a communist idealist, but he argues that he ‘could

change his mind entirely if it advanced his goal’.

I disagree with Sebestyen’s premise. In our age of ‘post-truth’ politics, with many politicians

focused on short-term electoral cycles, Lenin stands in stark contrast – regardless of one’s

views of his politics. He was convinced of the importance of leading a revolutionary

movement rather than listening opportunistically to the winds of popular change. Far from

‘post-truth politics’, he considered his a ‘politics of truth’. His goal was not power for its own

sake, but communism: a vision of a perfected society, whereby people would live in complete

social harmony. Communism, he believed, would bring with it the comprehensive

development and realisation of each individual. Unlike liberal capitalism, however,

individuals would only achieve this through collective social means. For communism to exist,

humanity would need to be improved and transformed. The core of the October Revolution,

then, was a vision of cultural revolution, that is, the creation of a new type of person, the so-

called ‘new Soviet person’ (novyi sovetskii chelovek). The October Revolution represented

the most ambitious and sustained attempt at human transformation and liberation in

modern European history. In failing to realise its ambitions, however, the Soviet regime

became the most violent state in European history.

'Under the Banner of Lenin', a double-portrait Soviet propaganda poster of Lenin and

Stalin, 1933.

What is Leninism?

The context for the development of Leninism was, initially, the Russia of tsarist autocracy,

wherein there was virtually no space for any legal political opposition. Our starting point

should be 1905. In that year, Russia experienced revolutionary upheaval that lasted into

1907, although the autocracy remained largely in place. During those years, we see Leninism

come into outline as a distinct version of Marxism, in response to the possibility that

revolution was on the immediate agenda in Russia. It was an especially uncompromising and

militant version of Marxism, born not only of the particular circumstances of autocratic,

underdeveloped Russia, but also of the particular conceptions of Lenin and his closest

comrades. Lenin was completely convinced that full-blown revolutionary civil war, in the

form of guerrilla violence and mass insurrections, would be necessary, if Russia was to

remove all of its remnants of autocracy and create a genuinely democratic republic with full

civil liberties.

Directness and decisiveness were characteristics of Lenin’s politics and leadership, reflecting

the militancy of his thought as well as the clarity and confidence that he sought to project in

his public pronouncements. They also reflected his impulse to hasten the dawn of socialism

in Russia. ‘Revolution’, Lenin wrote in 1905:

is a life-and-death struggle between the old Russia, the Russia of slavery,

serfdom, and autocracy, and the new, young, people’s Russia, the Russia of

the toiling masses, who are reaching out towards light and freedom, in order

afterwards to start once again a struggle for the complete emancipation of

mankind from all oppression and all exploitation.

What did Lenin mean by this, the idea of starting another struggle? Classical Marxist theory

suggests that history progresses through various stages, brought about by revolutions:

socialism would evolve into communism, but before socialism, there was capitalism.

Capitalism was associated with the political form of liberal democracy, which would allow for

the full development of commercial enterprise, but also the political maturation of the

masses through widening access to education, a free press and legal channels for political

action. The contradictions of capitalism would eventually lead to the working class revolting

and taking power themselves, under the guidance of socialist parties. Russia, according to

this schema, had not yet experienced its ‘democratic revolution’ à la 1789, which would

sweep away feudal autocracy. It was underdeveloped both socially and culturally and had few

democratic traditions. Lenin’s objective until 1917 was that the revolution would make a

decisive break with autocracy, thereby allowing the full flourishing of democratic liberties, in

order to advance more quickly to the next, higher, socialist revolution and the establishment

of full-blown socialism.

Class war

It was the First World War that helped bring about revolution in Russia and it was that

conflict that gave space for Leninism, as a distinct body of Marxist thought, to develop more

fully. Following the abdication of the tsar in 1917, Lenin thought that Russia was not yet

developed enough for socialism. Crucially, though, he thought that Russia was, as he put it,

on its ‘threshold’. What had changed was not simply the definite end of autocratic rule. Lenin

had come to realise, during the war, that Marx’s thought was out-of-date because Marx had

not lived through the age of imperialism as a fully formed and particular stage of capitalism.

Marxism now had to adapt to this new era. Developing his views on imperialism from the

works of other economists and socialists, Lenin (along with many other socialists)

understood the war as the inevitable consequence of imperialism, as a more aggressive form

of capitalism. Imperialism, he reasoned, had resulted from the fact that the logic of

capitalism’s pursuit of profit had driven capitalists and imperial states to conquer overseas

colonies, in order to exploit natural resources and cheap sources of labour. Rivalries between

imperial states for colonies had heightened international tensions.

Lenin believed that capitalism had entered its endgame; it had become so repressive that it

threatened civilisation itself. Imperialism had inaugurated a new era of violence and the

present war, as he put it, ‘will soon be followed by others’. The only solution for humanity

was international socialism brought about by global revolution. During the war, Lenin had

become convinced that the moment for such a historical necessity was now or never. The

war, then, had made socialism possible and, perhaps, relatively straightforward to achieve.

Wartime societies, Lenin thought, were ‘pregnant’ with socialism. His reasoning was that

imperialism was not just about overseas conquest; it had been facilitated by the

establishment of increasing economic concentration and monopolisation, whereby banks

had become fundamental to national economies. Economic centralisation and state control

had been given a major push by the exigencies of waging ‘total’ war. Lenin thought that this

had greatly facilitated the creation of rational, state-controlled but socialist economies,

because all that the working classes would need to do would be to seize control of the state

and to nationalise the banks and major industries. This was the theoretical foundation for

the October Revolution as a socialist revolution in a political sense: one that ended up with a

single radical left party (the Bolsheviks) in power. Lenin described the war as a ‘mighty

accelerator’ of history, hastening the process by which socialism would be achieved. He

thought that Russia’s path to socialism would be much shorter because of it, especially once

the Russian Revolution had helped ignite a revolutionary conflagration among more

advanced industrial societies, such as Britain and Germany.

Repressive state

The paradox of Leninism is that, as an ideology of popular emancipation and empowerment,

in power it became the theoretical basis of an extraordinarily repressive state. The

narrowness of democratic rights in Leninist thought, as well as the severe violence and

repression of the Soviet state against all opposition, soon became the targets of bitter

criticism by non-Bolshevik socialists inside and outside Soviet Russia. Within months of the

October Revolution, the Leninist enthusiasm for unleashing popular initiative and radical

democracy had given way to a more sober appraisal of the difficulties of building state

authority on the remnants of a failed state – and all during an economic crisis. Leninist

thought and Bolshevik rule became considerably more authoritarian. From the summer of

1918, the Soviet state intensified dramatically its use of violence and repression, responding

to deepening economic difficulties and civil war between supporters and opponents of the

October Revolution. All of this was justified in Leninist thought by reference to the better

future toward which the Revolution would lead. Lenin and his party would countenance no

major restrictions or inflexible legal checks on the powers of the revolutionary state.

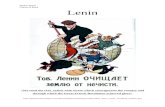

‘Lenin and the Proletariat’, anti-Soviet propaganda satirises Lenin the tyrant, Sergei Zhivotovsky, c.1919.

Before he died, however, Lenin oversaw a significant alteration in the course of the

Revolution. The New Economic Policy (NEP), which he introduced in 1921 in response to

major popular unrest with Bolshevik policies, suggested a slower, more moderate path to

socialism. In one of his final writings, from 1923, Lenin explained that ‘a radical modification

in our whole outlook on socialism’ was necessary. There needed to be a shift of emphasis

from political struggle to ‘peaceful, organisational, “cultural” work’. After his death in 1924,

Leninism remained the source of legitimacy of the party’s rule, but his ideology meant

different things to different people, at different times. Stalin declared in 1929, when

initiating an especially violent and rapid construction of the socialist state, that ‘destruction

of classes by means of bitter class struggle of the proletariat – that is Lenin’s formula’. He

was not wrong. To a significant extent, however, Stalin had taken Lenin’s thought out of

context and had hollowed out the meaning of Lenin’s last writings. Following Stalin’s death,

the Soviet Union became a less violent and slightly more open society. It was only in the late

1980s and early 1990s, when the unquestionable legitimacy provided by Lenin and

Leninism, as well as the party’s monopoly on power, were undermined, that the Soviet

experiment came to an end.

Is Leninism relevant today?

Leninism, then, is best understood as a historically specific understanding and application of

Marxism in order to bring about communism. Leninism and the Soviet state should not be

considered synonymous with socialism. Leninism was about communism and the salvation

of humanity from itself, about creating a society, which, as T.S. Eliot warned, was so perfect

no one would need to be good. It was motivated by impossible ideals of the complete

development of humanity and emancipation from all exploitation and unnecessary suffering.

It sought to achieve those goals, however, by encouraging class enmity and hatred; by the

practice and justification of an enormous amount of repression and violence; and by

establishing an authoritarian – more accurately, totalitarian – regime, under which millions

were to die. It was an extreme, absolutist political ideology, which allowed little room for

compromise. And yet compromises were possible, as demonstrated by the NEP. Lenin was

aware of the limits of violence and he might have been horrified to witness the violent

consequences of Stalinism. Many Soviet citizens, indeed many people throughout the world,

were enthused and mobilised by the Revolution’s rhetoric of empowerment, emancipation,

dignity and the chance to create a new life. Leninism is a complex bundle of irony and

contradictions, but its historic importance is undoubted. Is it still relevant though?

Western Europe and North America have, in recent years, witnessed a crisis in liberal

democracy. The politics of consensus around parties of the centre have been undermined.

The shortcomings of globalised capitalism led to the financial crash of 2008. Some

intellectuals on the far left have responded to the centenary of 1917 by suggesting that

progressives need to recapture the spirit of the age and that both the Revolution and

Leninism should be considered ‘unfinished’.

There are problems with this, one of which is the suggestion (mainly from liberals) that the

world is once again in a revolutionary situation. In reality, there are few indicators today that

(left-wing) revolutions are imminent, at least in economically advanced parts of the world.

What is crucial to understanding the Russian Revolution is that: first, the context was a

devastating and ‘total’ war that resulted in state failure and the collapse of four empires and,

second, Russia at the beginning of 1917 was an underdeveloped country ruled by an

uncompromising autocrat. Europe and Russia are very different from what they were in 1917

(Vladimir Putin notwithstanding).

Intellectuals on the far Left typically acknowledge that there are problems with Leninism’s

legacy. There is often, however, a lack of clarity about those mistakes and it is unclear what

bit of Leninism they think ought to be revived. There is usually an inability to acknowledge

that the major problems in Soviet history were effectively put in place under the leadership

of Lenin, Trotsky and their followers. A historical understanding of Leninism can only

conclude that it is incapable – even at enormous cost – of creating a better world. The Left

must remove itself from the long shadow of Leninism, however inspirational were the hopes,

ambitions and optimism of 1917.

Nonetheless, in an age of politics marked by cynicism, soundbites and distrust, when the

media often struggles to conceptualise political issues more deeply than in the short-term,

the trivial and the personal, there may be things to be learned from Leninism. The world

continues to be riven by problems of massive inequality, excessive corporate power,

corruption and warfare, as well as, more recently, problems of climate and environmental

sustainability. Leninism was an ideology of partisanship and sectarianism, of absolute

conviction in what it took to be truth. Soviet history teaches us the terrible dangers of all

that, but it should not invalidate a politics of principled conviction, opposed to a descent into

cynical relativism. That is needed today as much as a century ago.

James Ryan is Lecturer in Modern European (Russian) History at Cardiff University.

1. What was the argument being made by the historian?

2. What kinds of evidence did they use to back up their argument?

3. From what you’ve learned so far, do you agree?

4. Why / not?

5. What evidence would you use to back up your argument?

6. Why do you think your argument is stronger?

7. How might someone with a different view argue against you?

8. What if this was written by a Marxist?

Task 6 - Challenge Watch the 2 parts of the recent BBC News Documentary ‘Russia:

The Empire Strikes Back’. Then answer:

How has the collapse of the USSR influenced Russia since 1991?

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000j1s3

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000jcvf/russia-the-empire-strikes-back-series-1-2-

part-two

Task 5 - Challenge Why were there two revolutions in Russia in 1917?