MYSTERY BOULDERS OF GALINA POINT - University of the … Hazards/MYSTERY_BOULDERS.pdf · mystery...

Transcript of MYSTERY BOULDERS OF GALINA POINT - University of the … Hazards/MYSTERY_BOULDERS.pdf · mystery...

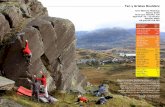

Hazards of the Jamaican Coastline MYSTERY BOULDERS OF GALINA POINT This is the second in a series of articles on Hazards of the Jamaican Coastline contributed by the Marine Geology Unit, Department of Geography and Geology, University of the West Indies. The Unit is headed by Emeritus Professor Edward Robinson. Edward Robinson Deborah-Ann C. Rowe Shakira A. Khan Contributors The three of us, from the Marine Geology Unit at UWI, had left Discovery Bay about an hour previously. From a hot, sunny morning there we were running into threatening weather, with low grey clouds scurrying across the sky. And now we had arrived at our destination and field objective – the lighthouse at Galina Point in the parish of St. Mary. We got out of the vehicle and looked around. The scene was one of desolation. On every side there was a flat expanse of sharp, jagged, pitted coral limestone, without soil or vegetation of any kind, close to the sea. Further inland, low bushes and shrubs, interspersed with a few small thatch palms, had taken hold on the bare surface. In front of us stood the lighthouse, a curious slender concrete structure, soaring skyward. Behind it the sea was heaving, throwing its waves against the low limestone cliff, every now and then raising a jet of foam into the sky. We had come to look for more examples of an unusual collection of rocks that we had seen on a previous trip to the area. Two months ago we had paid a brief visit to the southern part of Galina, and, in the fading light, noticed several large isolated boulders, resting on the pitted coral platform, looking like enormous chess pieces on a huge chess board. How did the boulders come to be here? From whence had they come? These were blocks of rock weighing several tons apiece. If this were Canada, the geological explanation that might spring to mind would be that they were glacial erratics, large rocks carried great distances by an ancient ice sheet. But this is Jamaica, not Canada. No evidence for glaciers has ever been verified here. Nor were there any nearby inland slopes down which the boulders could have rolled. So what forces could have moved rocks of this size? We left the area without having reached a definite conclusion, but determined to return to examine them properly. Well, here we were once again, and almost immediately we spotted the boulders, scores of them, sitting there on the flat limestone surface. They were much more numerous than we had previously thought. We set about our work, examining each boulder in turn, plotting its location on the ground with a geographical positioning system (gps), measuring its size, and looking at

1

its composition. Our investigations showed that the largest of the boulders measured nearly 6 metres in length, and was estimated to weigh over 100 tonnes, although most examples were much smaller. The boulders were made of hard limestone, mainly containing the fossilized remains of elkhorn corals. Today, elkhorn coral grows most profusely at the crest of the modern reefs. However, these boulders were evidently not from any modern reef, as the rock forming the boulders was dense and well lithified. They probably originated from near the crest of a fossil coral reef. Now, the modern platform on which the boulders rest is composed of rock that had originated as an ancient coral reef, that has since been raised some 5 to10 metres above sea level. These boulders, in fact, closely resembled those parts of the platform nearest to the sea. It seemed likely, therefore, that they had been torn from the seaward edge of the platform and rolled across it to finally rest further inland. Since that second visit we have measured over 180 boulders. They extend over one and a half kilometres along the Galina coast, mostly between 80 and 160 metres from the shoreline. Although the majority are less than 20 tonnes in weight, more than twenty are in the 40 to 60 tonne range, and two huge ones were recorded, both over 100 tonnes. One of the giants is about 40 metres from the shore while the other is 75 metres inland from the coast. A curious fact we noticed during our investigations was that, of all the 180 odd boulders, only three are less than 30 metres from the shoreline. Many of the blocks had plants, even shrubs growing on them, suggesting they had been there for some time. It is as if some giant hand had plucked each boulder from the cliff and flung it far inland from the shore. The question is, what natural processes have the ability to do this? A violent earthquake could shake the ground so forcibly that it might dislodge boulder-sized pieces of rock. But throw them all 150 metres in the same direction? One or more very intense hurricanes might have raised a storm surge sufficiently high and with enough wave energy to have torn the blocks from the shoreface and hurled or rolled them far inland. This is a more likely way of putting at least some of the boulders where we see them today. In a report on the effects of Hurricane Allen in 1980, Conliffe Wilmot-Simpson, then of the Government’s Geological Survey Division, mentions how the surge at Galina, with waves estimated to be 12 metres high, washed several tons of reef fragments and blocks into houses helping to destroy or damage seventy five buildings. In our own survey, eyewitnesses from the 1980 event identified boulders (from 1 to nearly 5 tonnes weight) that had moved during that storm. The Daily Gleaner, in its Disaster Preparedness Supplement for June 1, 1983, also carried reports of rocks being moved during Allen at Galina, at Manchioneal and at Trident Villas near Port Antonio, where a fair-sized boulder was flung into the lobby of the hotel. The most violent tropical storms known may have raised storm surges to heights of 10 or more metres, and storm waves as high as 20, perhaps even 30 metres, capable of moving rocks several tons in weight. The recent onslaught of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on the Gulf Coast of the United States produced storm surges seven or eight metres high, even after they were downgraded from category 5 to category 4 and 3 respectively. There are

2

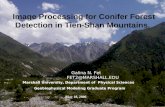

no rocky coasts along the Gulf of Mexico, so no boulders to be moved (although plenty of boats and buildings), but the reports indicate what such hurricanes can do. But how powerful would a storm have to be for its waves to carry a 100 tonne block 75 metres inland? Although there are a fairly large number of smaller boulders, lying about on the surface at Galina that could have been emplaced by hurricanes, it seems that the largest, heaviest blocks weigh much more than those that might be moved by even a very intense hurricane. Scientists who study sediment movement associated with such events have suggested that storm waves with this capability would have to be some 80 to 100 metres high. So, even the most intense hurricanes would likely be unable to move the largest blocks at Galina. The only known event that would generate waves of sufficient energy would be a tsunami, resulting from an earthquake, or displacement of the seafloor due to a submarine slide, as described in our previous article on coastal hazards. Because tsunami waves behave in a different way from hurricane-induced storm surges and wind-generated waves, and pack a much greater punch, the size of wave needed to move these massive boulders would be much less than those resulting from hurricanes. To get back to our story, we had previously been looking at a bank of coral fragments and debris that had been heaped behind the rocky coastline between Discovery Bay and Pear Tree Bottom in St. Ann. Here too were unusually large boulders, either sitting isolated on the rock surface, or associated with the debris bank. Since then we have identified big shoreline boulders and debris banks at several other localities in Jamaica, if you have any in your neighbourhood please let us know. As mentioned in our previous article, one of these localities is along the coast that extends all the way from Little Bay to Negril lighthouse, to the west of Savanna-la-Mar. Here, literally hundreds of boulders are scattered over a limestone platform similar to the one at Galina. Although detailed work in these areas is yet to be carried out, the largest block we measured was estimated to weigh as much as 140 tonnes, with many more in the 50 tonne range. As suggested in the accompanying photograph some of the boulders we have seen there and elsewhere are sitting very close to present and proposed coastal housing projects. Many appear to have been broken into smaller fragments by developers. What kind of a threat to coastal housing development is implied by the presence of the boulders? If we are looking at very severe hurricanes as the driving force behind boulder production and transport, then such storms would have to raise surge and wave runups of 20 metres or more, extending over the coastal platform and far inland to move some of the modest-sized rocks. It is almost certain that only tsunami events are capable of moving the largest blocks. How often are such events likely to occur? We have no definitive answer as yet, but one thing is clear. At Galina, the zone nearest the sea is free of boulders. Even as far inland as 40 metres, only a few of the larger blocks occur. Boulders of all sizes do not become common until the region between 80 and 160 metres away from the shoreline.

3

In one possible scenario the blocks may have all been shifted inland, perhaps bit by bit, perhaps by multiple wave events, until they reached positions where the incidence of intense storm or tsunami waves and run up has lessened to the point that they probably move only rarely. This implies that the boulder-free zone is swept by storms pretty frequently, perhaps by tsunami much more rarely, keeping it bare of deposits of all kinds, as well as most vegetation, and hurling freshly broken-off blocks well inland. In an alternative scenario all the blocks may have been flung to their present positions, 80 to 160 metres from the shore during a single, violent tsunami. Subsequent storms have merely moved some of the smaller ones around a bit and cleared off the finer sand and small stones. The real answer may be somewhere in between these extremes. After the melting of the glaciers of the last Ice Age the world sea level rose to more or less its present position some 4000 to 5000 years ago. Before that time sea level was probably too low for either storms or tsunami to have been able to fling rocks over what would then have been very high cliffs. So there has been about 4000 years during which today’s collection of boulders could have accumulated. Why is this important to us today? The implications evident from the observations by our research team seem to be that there is an excellent record, provided by these rocks, of past large tsunami events affecting the Jamaican coastline. Also, if you are determined to build a house on one of the limestone terraces along the southwest coast, and you want it to be free of storm damage for 50 years or more, it might be best to build well away from the coast itself. If the area near to the sea is clear of debris and vegetation, it’s probably not because it was waiting for you to build on it. The sea most likely keeps it swept so perhaps you shouldn’t build there either. And, if you have yet to invest, take a look and see if there are any boulders lying around nearby…. If storms and tsunami can hurl boulders many metres inland from the cliffs, what are they likely to do to the nearby beaches? We will be saying more about melting ice sheets, sea level rise and building setbacks in our next article on the hazards of the Jamaican coastline. The Marine Geology Unit; [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to colleague Gail Simpson and to Jody Dixon for assistance in the fieldwork. This study forms part of the BEACHES project funded by the Environmental Foundation of Jamaica. We have also received much encouragement from the Geological Society of Jamaica, celebrating its 50th Anniversary this year.

4

This limestone boulder at Galina Point is about 120 metres from the sea.

Measuring a limestone boulder near buildings on the Jamaican south coast.

5

Breaking waves carrying boulders across a rocky shoreline.

6